Neville Chamberlain, with the famous umbrella.

Neville Chamberlain, with the famous umbrella.

AT HOME PREPARATIONS for war had been going on since the German seizure of Prague in March 1939. Trenches had been dug close to our house on Hampstead Heath, for what purpose it was not clear. Instructions had been given to every householder on how to prepare “blackout” curtains in case war came. We had been issued gas masks that had to be carried at all times—mine came in a small, square brown canvas-covered cardboard box, with a flimsy string so that it could be slung over the shoulder. (A special one like a rubberized canvas sack with a transparent face shield was even available for babies.)

It was, in those last few days of peace, firmly believed that if war came it would begin with a massive bombing raid that would destroy London. This belief had been stated by former Prime Minister Stanley Baldwin, who summed it up in the House of Commons as “The bomber will always get through,” a phrase borrowed from the Italian theorist of air warfare Giulio Douhet in his influential book Command of the Air—strange reading for Baldwin, who usually napped through discussions of foreign policy and military planning at the cabinet (“Wake me when this is over,” he would say to anyone sitting beside him) and whose usual reading was Thackeray or Trollope. It became the strategic policy of the Royal Air Force, not that RAF Bomber Command in 1939 had the aircraft or the technology with which to destroy targets in Germany—nor would the British or the French government have allowed them to do so, since it was feared that whoever first killed “women and children” by bombing would bring about a devastating retaliation by the Luftwaffe on London and Paris. French governments were especially determined not to risk German bombing of Paris, and therefore not to give Hitler any excuse to bomb it.

The fear that war would begin with a huge aerial attack using high explosive and poison gas to kill large numbers of civilians was pervasive, and it helps to explain the reluctance of the British and French governments to challenge Hitler. The British government was not only issuing gas masks and instructions for blackout curtains but, unbeknownst to the public, was also selecting sites for mass graves and ordering thousands of cheap, mass-made cardboard coffins.

Quite inadvertently my father, Vincent, had been partly responsible for the widespread belief that the war would begin with a massive assault from the air. My uncle Alex’s film Things to Come, perhaps the most ambitious science-fiction motion picture of the era, began with a long, immensely convincing sequence of London (named Everytown in the film, but with the ruins of St. Paul’s Cathedral and Covent Garden clearly identifiable) being destroyed from the air in a surprise attack, followed by Armageddon as the survivors flee from the city’s ruins and civilization collapses.

One of Vincent Korda’s sets for Things to Come.

So striking were my father’s designs for this scene of mass destruction (he was helped in creating it by his Hampstead neighbor and fellow countryman the constructivist visionary and futurist László Moholy-Nagy) that it imprinted itself on the mind of many people, including two prime ministers, Stanley Baldwin and Neville Chamberlain, and the editor of the Times Geoffrey Dawson, as well as the general public. It even impressed Hitler when the film was screened for him in Berlin. Audiences everywhere were stunned as the sky was darkened by masses of bombers like huge flocks of black, predatory birds, saturating Everytown with high explosives and poison gases, against eerie background music by the distinguished composer Sir Arthur Bliss.

This vision of instant mass destruction—soon enough to become commonplace throughout Europe—prompted otherwise comparatively sane civil servants to prepare for the worst. Plans were laid to “evacuate” more than a million children from major cities. Operation Pied Piper, as it was called (somebody in the Home Office must have had a sense of humor), would eventually evacuate almost three and a half million people, most of them to “reception zones” in the country, some of them, including myself, overseas to British Dominions or the USA. In keeping with its belief in the efficacy of the bomber, the Air Ministry estimated in 1938 that there would be at least sixty-five thousand civilian casualties in the first week of war and a million in the first month, while at least three million refugees from the destroyed cities would flee to the countryside, causing “total chaos and panic” and creating social disorder and disease. Responding to these wildly alarmist estimates from the Air Ministry, the Home Office had over a million emergency death certificates printed and distributed in advance to local authorities.

When we arrived home in London nothing seemed to have changed, except that we were reunited with our gas masks, but outside our blackened brick garden walls in Hampstead events were moving at a rapid pace. Since March 1939 Hitler had been agitating about the return of the Baltic port city of Danzig to Germany and a solution to the so-called Polish Corridor, separating East Prussia from the rest of Germany. The Treaty of Versailles (1919) had created this “corridor” linking Poland to the Baltic Sea, thus separating East Prussia from West Prussia, and placed the “Free City of Danzig,” with a majority of Germans, under League of Nations rule to award the Poles a seaport. Danzig even had its own currency, its own postage stamps (prized by collectors today), a national anthem, and its own “League of Nations High Commissioner,” a Swiss diplomat who attempted to govern a city in which even the smallest, most everyday matters were a subject of fierce dispute between German and Polish residents. Danzig and the corridor represented a grievance to all Germans, even those who were anti-Nazi, and there were few people in Britain or France who would or could defend it.

Hitler’s original demand had been for an “extraterritorial” highway across the corridor, linking East and West Prussia—Germans crossing the corridor complained of being singled out for unreasonable and intrusive searches and delays by Polish customs officers and police—and for the return of the city of Danzig to German rule. A negotiated settlement along these lines might well have succeeded, except for the fact that Polish Minister of Foreign Affairs Józef Beck, a slippery character at best, was unwilling to negotiate. He had only to look at what had happened to Czechoslovakia the year before—first the Czechs lost the Sudetenland, and with it their defense line against the Germans, then what remained of their country was taken from them by brute force, now they were ruled by a Nazi “Reich Protector of Bohemia and Moravia” in Prague, backed up by the SS and the Gestapo. Poland, like Hungary, had shared in the spoils, annexing parts of Czechoslovakia that adjoined Poland, so Beck was no stranger to the process of divvying up a small country in Eastern Europe, or to the Nazis, with whom he shared a strong degree of anti-Semitism and a preference for autocratic rule as opposed to democracy.

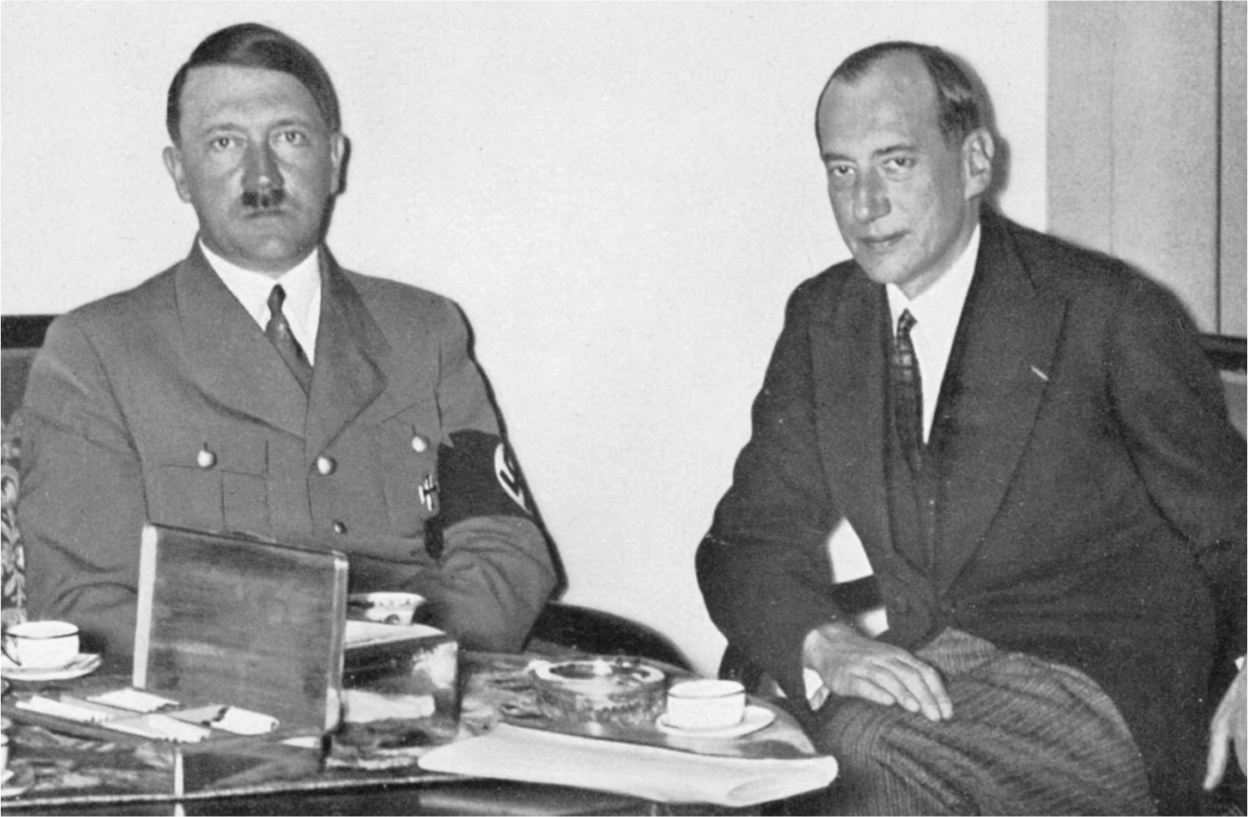

Hitler and Polish foreign minister Józef Beck.

Beck did not create a good impression on anyone. Hitler despised him—there is a revealing photograph of Hitler and Beck meeting over tea in the Reich Chancellery that shows the Führer sitting stiffly and staring at the camera in sullen rage while Beck lounges beside him gracefully, a diplomat’s smile on his face as if he and Hitler were best friends. In London, Beck’s stubborn refusal to listen to the advice of his allies, and his serene confidence that he was in control of events, strained the patience of both Chamberlain and Foreign Secretary Lord Halifax. In Paris, the dawning realization that French foreign policy was now, thanks to Britain, a hostage to Beck’s skill as a negotiator, filled everyone in the government with a curious mixture of horror and fatalism, like people being swept inexorably toward Niagara Falls in a canoe without a paddle.

On a visit to London early in 1939 Beck blithely reassured Chamberlain that he doubted “whether there was ‘any serious danger’ of German aggression,” and downplayed the importance of Danzig and the corridor, asserting that the whole matter was “not in itself a grave one.” Beck did not explain why Poland had been so eager to obtain a guarantee from Britain and France if there was no grave threat from Germany, nor did he reveal that Józef Lipski, the Polish ambassador to Germany, had already been treated to an icy and “violent” demand from German Foreign Minister von Ribbentrop for the immediate return of Danzig and a German road across the corridor. Beck told Chamberlain and Halifax what they wanted to hear—that there was no threat to Poland, and therefore no likelihood that Britain and France would be called upon to fulfill their guarantee to defend it. For their part they were more concerned to persuade the Poles not to provoke Hitler than to come up with any reasonable strategy for defending them.

Despite his demand for Danzig and the corridor and the intense diplomacy taking place over it, Hitler had already made up his mind to attack and annihilate Poland. We now know that as early as April 3, 1939, he had issued “War Directive No. 1,” stating that his intention was “to settle the account for good” and “to smash the Polish armed forces.” The operation was code-named Fall Weiss (Case White) and opens with this brisk statement: “Since the situation on Germany’s Eastern frontier has become intolerable . . . I have decided upon a solution by force.” The military was ordered to complete full preparations for an attack that was to be launched on September 1, 1939. At the same time “the conversion of the entire German economy to a war basis [was] now decreed.” In the meantime, the British and the French worked hard to persuade the Poles to undertake negotiations with Germany for the peaceful return of Danzig and a road across the corridor, causing the British ambassador to Poland to complain, “If we are not careful [the Poles] may think we are getting cold feet.”

The Poles, however, resisted stubbornly, while at the same time playing down the seriousness of the crisis. They rejected Chamberlain’s proposal for an alliance of the smaller East European countries (Hungary and Romania), afraid that any such attempt would trigger a violent German reaction. They refused to cooperate with British and French negotiations for an alliance with Soviet Russia, since from the Polish point of view Russia was an even more dangerous enemy than Germany. Besides, the Poles had no great opinion of the Red Army, which they had defeated at the gates of Warsaw only eighteen years previously, and even Chamberlain had to admit that he had “no belief in [Russia’s] ability to maintain an effective offensive even if she wanted to,” hardly an opinion calculated to persuade the Poles to allow their powerful neighbor to the east to cross the Russo-Polish frontier in the case of a German attack on them.

Nor did the French and the British make any sensible provision for military aid to the Poles. Neither of their countries had any way of reaching Poland by land. In the case of war the French Army would be deployed defensively behind the Maginot Line, which would hardly be of much help to the Poles. As for the British, they were in no position to provide modern fighter aircraft to the Poles, besides which the British government was in any case hoping to be “the honest broker” of a peaceful international negotiation to solve the problem, rather than encouraging the Poles to fight. Even negotiations for a British loan that would enable the Poles to buy British arms was allowed to bog down because of the Treasury’s pessimism about the value of the zloty and the ability of Poland to repay it.

Hopes that Mussolini would repeat his role as a peacemaker during the Munich crisis by persuading Hitler to accept another negotiation with Britain and France intended to impose a settlement on the Poles flickered throughout the early summer of 1939. It was a role that Mussolini was eager enough to play, especially since he knew better than anyone else that, given the state of Italy’s armed forces, he would have to disappoint Hitler by not going to war beside him, but this time Hitler did not want to settle for a mere slice of the pie; he wanted the whole thing, and by seeking an alliance with Stalin he knew he was going to get it.

Mussolini’s smooth, but realistic, foreign minister and son-in-law, Count Galeazzo Ciano, who was trying to produce a diplomatic solution to the problem, learned from his German counterpart Joachim von Ribbentrop that there was no hope of a peaceful solution. Walking with him before dinner in Salzburg, Ciano asked, “Well, what do you want, Ribbentrop? The Corridor or Danzig?”

Ciano and Ribbentrop.

“ ‘Not that anymore,’ Ribbentrop said, “gazing at me [Ciano] with his cold, metallic eyes. ‘We want war!’ ”

There has been a tendency among historians to doubt Ciano’s account of this conversation, since it was written shortly before his execution by a firing squad on the orders of his own father-in-law in December 1943, but there seems no reason why a doomed man would necessarily invent words; on the contrary, it seems more likely that he would record the truth. Certainly it sounds like Ribbentrop, who was notorious for coldly repeating his master’s voice, as well as for his lamentable gaffes as a diplomat, such as giving the Nazi salute when he was presented to a startled King George VI as German ambassador to the Court of St. James, and complaining afterwards because the king did not return it. Even Ribbentrop’s fellow Nazis complained about the snobbery, ignorance, and slavish sycophancy of the ex-champagne salesman turned expert on foreign affairs whom Hitler constantly praised as “a second Bismarck.” When Hermann Göring complained to Hitler about him, the Führer rather weakly defended Ribbentrop on the grounds that he knew the English. “Perhaps,” Göring replied skeptically, “but the problem is that they know him.”

No one factor is sufficient to account for the outbreak of World War Two—great events inevitably have many causes—but there is no doubt that Ribbentrop’s misreading of the English, and Hitler’s misplaced confidence in his obsequious foreign minister’s opinions, played a major part. Hitler’s own knowledge of the English was limited to Chamberlain and Halifax, and to the succession of visitors who came to pay homage to him in the thirties like the Marquess of Londonderry, David Lloyd George, and the Duke and Duchess of Windsor, all of whom were eager to reach a mutual “understanding” between Great Britain and Germany, and therefore unlikely to argue with Hitler, or tell him what he did not want to hear. As for Ribbentrop, his knowledge of the English was limited to the wealthy, upper-class appeasers he admired, and was so superficial that he reported home that the abdication of King Edward VIII was the result of a plot by Jews and Freemasons, two of the major bêtes noires in the Nazi mind.

Neither Hitler nor Ribbentrop appreciated the degree to which Chamberlain felt personally betrayed by the seizure of the rest of Czechoslovakia in March 1939, nor the subtle shift in the opinions of all but the most determined of British appeasers as Hitler began to annex or threaten areas that did not contain a majority of ethnic Germans. The British were not ready for war, and certainly not eager for it, but even in the Conservative Party there were rumblings of discontent amid the apprehension. It was still mostly from the few “glamour boys” around Anthony Eden, or “the Gangsters,” as Churchill’s small circle of admirers was known within the party, based on the dislike among the rank and file for such “flashy” friends of Churchill’s as Brendan Bracken and the wealthy newspaper tycoon Lord Beaverbrook (caricatured as “Lord Copper” in Evelyn Waugh’s novel Scoop), but there was also a growing feeling of uneasiness in the party about the possibility of repeating the Munich settlement of 1938 in Poland. Despite this Chamberlain’s majority in the House of Commons was huge, over two hundred, and secure, the bulk of Conservative members of Parliament were loyal to him—their loyalty kept fiercely in line by the formidable chief whip, Captain David Margesson—and he retained an immense authority and personal popularity, in politics, in the media and among the public, as well as with the royal family.

Hitler greets HRH the Duke of Windsor and the Duchess, October 1937.

Although Chamberlain has been criticized for doing “too little, too late,” as the end of August approached, preparations were made to mobilize the fleet and the Royal Air Force, to recall army reservists and Territorials, and to make final preparations for a blackout—quiet, but unmistakable, warnings to the Germans that the invasion of Poland might have serious consequences.

Sir Nevile Henderson and Göring.

These warnings Hitler ignored—or more likely he did not take them seriously. The German Army and the Luftwaffe were fully mobilized along the border with Poland, nobody could mistake these preparations for peacetime maneuvers, while German diplomacy marched beside the army, becoming daily more threatening toward Poland. On August 25, in response to numerous British and French “peace feelers,” both through their ambassadors in Berlin and to Mussolini, Hitler confided to the British ambassador Sir Nevile Henderson “that he accepts the British Empire and is willing to pledge himself to its continued existence,” provided that Germany’s former colonies were returned and that the “German-Polish question” was resolved.

Sir Nevile, a longstanding and determined appeaser, whom many accused of groveling to Hitler, flew to London at once to communicate this offer to the government and seek a reply to bring to Hitler, but Chamberlain and Halifax were taken aback by Hitler’s grandiose offer to guarantee the existence of the British Empire, however conditionally. To even the most stalwart of appeasers this had the ring of hubris.

It proved more difficult to obtain a reply to Hitler’s offer than Henderson had presumed. The first draft seemed to some members of the cabinet “fulsome, obsequious and deferential,” quite apart from skating lightly over Britain’s obligation to defend Poland including Danzig and the corridor. In order to prevent a revolt within the cabinet the draft was revised several times, but it still seemed a weak response to Hitler’s threat to go to war with Poland if he did not get what he wanted.

By the last week of August, the situation had been further complicated by the appearance on the scene of Birger Dahlerus, a well-connected Swedish businessman who traveled back and forth between Berlin and London bearing messages to and from Field Marshal Göring in a last-minute effort to inform the British government of exactly what Hitler would (and more important would not) accept in their reply to his “offer.”

The intrusion of Dahlerus as a kind of Swedish deus ex machina is an indication of just how determined Chamberlain and Halifax were to preserve peace at the expense of Poland, and of their own misreading of German politics, if the word “politics” can be applied to government by a dictator. It suited Chamberlain and Halifax to believe that Göring was a mollifying influence on Hitler, even that Göring was a possible alternative to him, a delusion that Sir Nevile constantly reinforced from Berlin.

Göring’s expansive, bluff charm, his supposed Anglophilia, his passion for upper-class blood sports, and his lavish, self-indulgent life style all combined to make him seem like a more approachable figure than the remote, abstemious, vegetarian Führer, with his sudden rages and bullying negotiating style. Halifax had described Göring in admiring English upper-class terms that make him sound like a character in a Nancy Mitford novel: “a great schoolboy . . . a composite personality—film star, great landowner interested in his estate, Prime Minister, party manager, head gamekeeper at Chatsworth.”*

Whereas Chamberlain and Halifax supposed that Göring was the “good” face of Nazism and overlooked his record of brutalities, the truth was that Göring was slavishly devoted to the Führer, and never dared to argue with him. Like so many less important Germans, Göring too went “weak at the knees” at one gaze from those glaucous, hypnotic blue eyes. In fact Göring’s involvement in the Anglo-German crisis was carefully stage-managed by Hitler himself, an illusion intended to distract the British leaders and give them the impression that there existed a “moderate” element in the Nazi government. No such moderate element existed, of course, from the Nazi regime’s beginning to its sordid end.

Göring and the Führer.

Dahlerus has come in for a good deal of criticism for his part in this deception, but he seems to have believed sincerely, even desperately in his role as a peacemaker and, more important, in Göring’s supposed desire for peace and ability to restrain Hitler. Had the British investigated the supposedly neutral Dahlerus, they would have discovered that he was pro-Nazi, married to a German woman, and a useful tool for Göring since 1934, but clutching at straws, they took him at his own self-inflated importance.

By August 28 Chamberlain and Halifax, without consulting the cabinet, had already passed on to Dahlerus Britain’s willingness to persuade the Poles to give up Danzig and the corridor, and heard back that they would also have to persuade the Polish government to send a negotiator, presumably Colonel Beck, to Berlin at once. This was a role that Beck refused to play.

Through August 29 and 30 the Germans turned up the heat, demanding that Poland initiate “direct discussion” immediately with the German government. Hitler now openly spoke of “annihilating Poland,” going far beyond his previous demand for Danzig and the corridor, and even the mild-mannered Henderson, whose sympathies predictably lay with the Germans rather than the Poles, found himself in a shouting match with Hitler, telling the Führer that “if he wanted war . . . he would have it.” Unusual as it was for a British ambassador to lose his temper at the head of state to whom he had been accredited, it was followed by twenty-four hours more of extraordinary attempts to bully the Poles into sending a major figure of the Polish government to Berlin without any preconditions in order to learn the full extent of the German demands to which the Poles would have to agree in advance.

Only a year before, during the Sudetenland crisis, Halifax had expressed to another German amateur diplomat that he hoped to see “as the culmination of his work, the Führer entering London, at the side of the English King, amid the acclamation of the English people.” Whether Halifax actually used those exact words as they were reported to Berlin is hard to know, but if so they reveal an altogether unexpected gift for fantasy in the normally neat and cautious mind of the British foreign secretary. In any case, this hope was by now rapidly receding into the province of daydreams. The British government was informed that Hitler was drawing up a list of his demands on Poland, and that the Poles must send a representative to receive them immediately, but by the time the sixteen demands were finally produced in written form the deadline had passed. In any event, Hitler had already decided on war, and refused to receive the Polish ambassador or to accept Mussolini’s offer to call for an international conference to take place in Italy on September 5.

Lord Halifax and Göring.

An “incident,” however, was still needed to justify the German attack, and orders to produce one had already been given to SS Gruppenführer Reinhard Heydrich, the dreaded chief of the Sicherheitsdienst, who had orchestrated the Kristallnacht program in November 1938 and the roundup of the Austrian Jews after the Anschluss, and who would soon be called upon to organize the death camps and the killing squads. Heydrich had, along with a gift for organization and consummate, cold-blooded brutality, a vivid imagination and a knack for propaganda. He arranged a carefully staged attack on a German radio station at Gleiwitz, in Upper Silesia near the Polish border. In order to make it look more convincing, he had several prisoners from Dachau concentration camp dressed in Polish uniform and shot so that it would look as if they had been killed during an “attack” on the station. The prisoners, in the merciless tradition of the SS, were cynically code-named Canned Goods for the purposes of the operation, and their bodies were exhibited to the neutral press as proof of a serious Polish provocation.

* * *

This and several other bogus border “incidents” were preludes to the full-scale attack on Poland that began at 4 a.m. on September 1. The Germans attacked with two armies, comprising sixty divisions, nine thousand guns, nearly three thousand tanks, and over two thousand aircraft. It was an overwhelming force, over twice the size of the Polish Army, which was not as yet fully mobilized and which was markedly, but not surprisingly, deficient in tanks and aircraft. Perhaps to demonstrate Hitler’s contempt for the Poles and his intention to wipe their country off the map of Europe, the attack was not preceded by a declaration of war—indeed it took place while the Polish ambassador in Berlin was still struggling to convey Hitler’s sixteen demands by telephone to his government in Warsaw.

The Poles fought valiantly, but inevitably they were pushed back. It did not improve their morale that their British and French allies not only did nothing to support them but delayed declaring war on Germany for over forty-eight hours. The indefatigable Dahlerus was on the telephone from Berlin, offering to fly to London immediately and passing on Göring’s lame assurance that only military targets would be bombed, even though three major Polish cities had already been attacked by the Luftwaffe, with considerable civilian casualties.

To the dismay of the Poles the British still hoped for a negotiated solution, and prepared a carefully drafted note “warning” that if the Germans did not suspend their invasion of Poland and agree to withdraw their troops His Majesty’s Government might be compelled to fulfill their obligations to Poland. As if to rub salt deeper into Polish wounds, Halifax specifically requested the British ambassador in Berlin to make it clear that the note was only a warning, not an ultimatum. Henderson presented the note to Ribbentrop at 9:30 p.m. in a meeting that he later described as “courteous and polite” for a change. He asked for an “immediate” reply, but Ribbentrop said he could not give one until he had consulted with the Führer, who was in no hurry to read it.

By the morning of Saturday, September 2, the full violence of modern war had spread far and wide across western Poland while its allies struggled to avoid declaring war. Frantic telephone calls between Halifax and Georges Bonnet, his French counterpart, led to a succession of failed attempts to get Hitler to agree to a negotiation, but in the meantime two new factors surfaced. The first was that of public opinion in Britain—little as the British wanted war they, unlike their government, had no difficulty in recognizing German aggression when it took place. Even within the ranks of the Conservative Party there was some discomfort at the government’s failure to support the Poles. The second, and more remarkable, factor was Neville Chamberlain’s growing conviction—a historical fact long since forgotten—that before any conference could take place German troops must be withdrawn from Poland.

The prime minister had always possessed a firm and unshakable sense of right and wrong, which was at the heart of his intense dislike of Lloyd George, whose standard of personal and political morality was notoriously low, and once a moral imperative had entered that austere and logical mind, there was no hope of removing or softening it. Chamberlain was still anxious for a conference and hopeful that the Poles could be persuaded to give Hitler what he said he wanted, but he was determined that German troops must leave Poland first. The French had already gone behind the back of their British ally to renew their appeal to Mussolini to get Hitler to the conference table, but as Ciano pointed out to them, the British demand that German troops withdraw first was unrealistic.

The French had by this time reached the same conclusion themselves. The Germans were advancing. German bombs were falling on Warsaw. Nobody could imagine that Hitler would end a war he could already sense he was going to win, or humiliate his generals by ordering them to withdraw. The German generals had been aghast when he proposed to remilitarize the Rhineland in 1936, and they had been reluctant at the prospect of fighting in Austria and against the Czechs in 1938, but each crisis had proved them wrong. They had all been Blumenkriege, “flower wars,” triumphant victories in which no blood was shed. Now they were fighting a real war. Their enthusiasm was higher and their confidence in the Führer, though never complete given the aristocratic background of many of his generals, was also greater. Hitler could not afford to lose their confidence by giving in to the British demand, even had he been so inclined.

The fact that the British and French had not yet declared war seemed to him proof that he would be able to eliminate Poland without a war in the west.

_________________________

* Chatsworth House is the seat of the immensely rich Duke of Devonshire. Think Downton Abbey, but vastly bigger and more elegant.