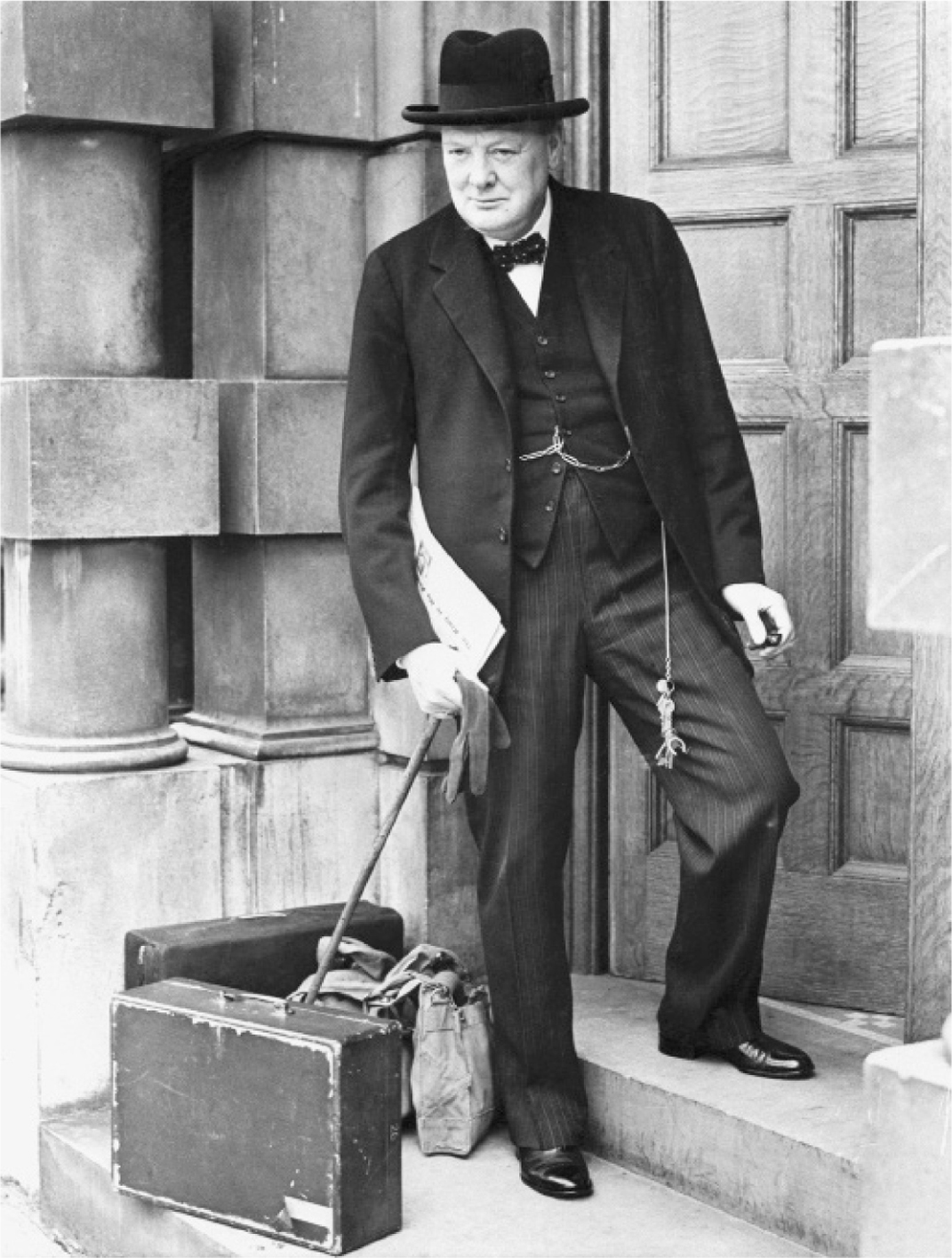

Winston Churchill arrives for his first full day back as first lord of the Admiralty.

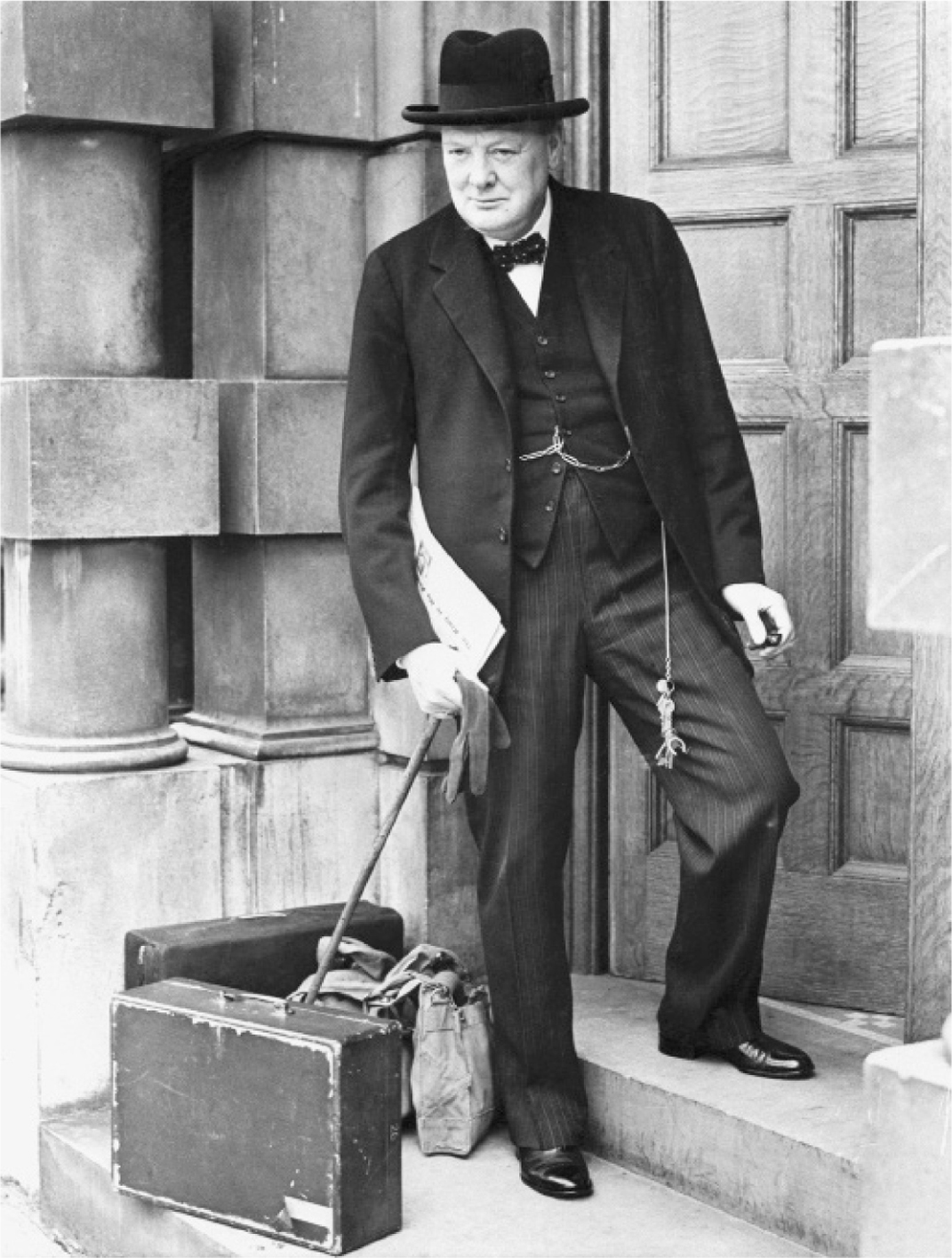

Winston Churchill arrives for his first full day back as first lord of the Admiralty.

ALL THAT WAS about to change. At 7:30 p.m. on Saturday, September 2, the House of Commons met. The House was packed, and tension was extraordinarily high—the members on both sides of the House, even those who had been loyal appeasers until now, were expecting Chamberlain to announce an ultimatum.

It was a moment for firmness and an inspiring, historic speech. Instead, Chamberlain explained in a low key that the government was still trying to arrange for “a discussion” between Germany and Poland. “If the German Government should agree to withdraw their forces,” the prime minister said to a surprised and hostile House, “then His Majesty’s Government would be willing to regard the position as being the same as it was before the German forces crossed the Polish frontier.”

These words, spoken while Warsaw was being bombed, had the worst possible effect on the House. Chamberlain himself had an almost superhuman ability to control his own emotions, and a sublime objectivity—without which he could hardly have sat through three grueling meetings with Hitler—but as a consequence he failed at this crucial moment to understand his audience, which by and large reflected the view of the British people. Chamberlain’s goal was peace for Britain, and he knew that peace could not be obtained without satisfying Germany’s demands for the revocation of the terms of the Versailles peace treaty. What mattered to him was to keep that goal in mind, no matter what difficulties arose. He would not be provoked, he would not give way to emotion rather than reason, he would, if necessary, turn the other cheek. He put the position plainly to the House and expected that all but the firebrands would accept it, as most of them had accepted (and rejoiced over) the settlement he had brought home from Munich a year earlier. But 1939 was not 1938. “The house was aghast,” wrote one Conservative member. Chamberlain’s speech was followed not by cheers but by an appalled silence.

When Arthur Greenwood rose to speak for the Labour opposition (the Labour leader Clement Attlee was sick), Leo Amery, an old friend and Harrow schoolmate of Churchill’s, shouted out from the Conservative back benches, “Speak for England!”

Greenwood was no spellbinding orator; he was a stiff-collared and colorless socialist theoretician, whose chief claim to fame was that he combined being the author of a book on “public ownership of the liquor trade” in favor of nationalization and prohibition with a reputation for heavy drinking. In his fumbling way Greenwood attempted to warn that every minute’s delay could only lead “to more loss of life,” and imperil “our national interests.”

Attlee.

From the Conservative back benches Robert Boothby, another friend of Churchill’s, shouted out, “Honor,” so Greenwood went on to add, “Let me finish my sentence. I was about to say—imperiling the foundations of our national honor.”

Robert Boothby.

The word resonated in the hushed chamber. Greenwood, perhaps not the most likely spokesman for old-fashioned patriotism, had expressed not only what the House was feeling but what the whole country had been coming, with whatever reluctance, to feel over the past two days—that Britain’s honor, not just its “national interests,” was at stake. For better or for worse Britain had made itself an ally of Poland, and Poland was under attack—there could be no further delay in declaring war on Germany, whatever the French decided to do.

Chamberlain sat white-faced as the debate proceeded, and when it was over he retired to his room in the House of Commons to face the anger of most of his own cabinet. The House could not be held, he was told even by his own closest supporters—the government might fall unless the prime minister could announce that a firm ultimatum had been sent before the House met again on Sunday. After an evening of soul-searching interrupted by anguished telephone calls from Warsaw for help, and from Paris for more delay, Chamberlain made the only decision that could save his government—an ultimatum would be delivered to the German government at 9 a.m. the next morning, to expire at 11 a.m.

Sir Nevile Henderson in Berlin was instructed late Saturday night to ask for an appointment to meet with Ribbentrop at 9 a.m. on Sunday morning, September 3, followed by the text in code of the ultimatum he was to present. The French, aghast, would lag two hours behind the British, after making yet another feeble attempt to persuade Mussolini to intervene, the text of which Ciano threw into his wastepaper basket contemptuously “without informing the Duce.”

In the event, Ribbentrop, once he had been informed of Sir Nevile’s request, decided not to meet with him personally, and delegated Paul Schmidt, the German Foreign Office interpreter, to stand in for him. Fortunately Schmidt knew Henderson well and made a record of the meeting.

Henderson was announced as the hour struck. He came in looking very serious, shook hands, but declined my invitation to be seated, remaining solemnly standing in the middle of the room.

“I regret that on the instructions of my Government I have to hand you an ultimatum for the German Government,” he said with deep emotion, and then, both of us still standing up, he read out the British ultimatum. “More than twenty-four hours have elapsed since an immediate reply was requested to the warning of September 1st, and since then the attacks on Poland have been intensified. If His Majesty’s Government has not received satisfactory assurances of the cessation of all aggressive action against Poland, and the withdrawal of German troops from that country, by 11 o’clock British Summer Time, from that time a state of war will exist between Great Britain and Germany.” . . .

I then took the ultimatum to the Chancellery, where everybody was anxiously awaiting me. Most of the members of the Cabinet and the leading men of the Party were collected in the room next to Hitler’s office. . . .

When I entered the next room Hitler was sitting at his desk and Ribbentrop stood by the window. . . . I stopped at some distance from Hitler’s desk, and then slowly translated the British Government’s ultimatum. When I finished, there was complete silence.

Hitler sat immobile, gazing before him. He was not at a loss, as was afterwards stated, nor did he rage as others allege. He sat completely silent and unmoving.

After an interval which seemed an age, he turned to Ribbentrop, who had remained standing by the window. “What now?” Hitler asked with a savage look, as though implying that his Foreign Minister had misled him about England’s probable reaction.

Ribbentrop answered quietly: “I assume that the French will hand in a similar ultimatum within the hour.”

. . . In the anteroom, too, this news was followed by complete silence.

[Then] Göring turned to me and said: “If we lose this war, then God have mercy on us.”

Americans of an advanced age can usually remember exactly where they were and what they were doing when the news of the Japanese bombing of Pearl Harbor was announced on the radio. I am one of a fast-diminishing number of Britons who also heard Neville Chamberlain’s announcement that we were at war with Germany.

The only radio in the house was in the kitchen—an admiring visitor from Hollywood had brought it as a gift to my father, in the days when a portable radio was still an American marvel, something one saw in American films and magazines, a radio you could take to the beach with you, or to the swimming pool. I think it was a Zenith, a big, heavy black leather-covered box with a brushed stainless-steel handle and lots of shiny chrome. My father had exiled it to the kitchen since he hated noise of any kind, and it was only played while he was away at work. With some ceremony it was brought into the dining room, placed on the table, and turned on while we sat around it as if it were some mysterious object of worship, its rectangular tuning dial glowing fluorescently, the hint of much technology to come, most of which my father would resist having in his home—this despite the fact that we had all been taken to Alexandra Palace one rainy afternoon to watch my mother appear singing and dancing on the tiny screen of the BBC’s experimental television program in a room half filled with mysterious circuitry like something out of an H. G. Wells novel.

My father sat quietly, eyes closed as if in pain. I sat next to my mother, who was incapable of not looking cheerful and glamorous, whatever the occasion. Nanny Low and the Hungarian cook in her white apron stood behind the radio, perhaps because they were the only people in the house who knew how to turn it on. My father’s wirehaired fox terrier Jani (an affectionate diminutive of the Hungarian name János, or Johnny), who accompanied him to the studio every day, lay beside him, apparently attuned to some kind of drama. Beyond the French windows was the small garden and the brick wall that separated the house from the street—a neat, tidy world about to be disrupted. The solemnity of the occasion, and my father’s expression kept me from fidgeting or asking questions—silence was clearly called for.

At exactly 11:15 a.m. the somber voice of the prime minister speaking for the first time from the Cabinet Room in 10 Downing Street came on after a brief announcement: “This morning the British Ambassador in Berlin,” Chamberlain said, “handed the German Government a note stating that unless we heard from them by 11 o’clock that they were prepared at once to withdraw their troops from Poland a state of war would exist between us. I have to tell you that no such undertaking has been received, and that consequently this country is at war with Germany.”

He went on, “It is evil things that we shall be fighting against—brute force, bad faith, injustice, oppression and persecution—and against them I am certain that right will prevail.”

For some reason, Chamberlain has never been given his due as a speaker—he had a deep, sonorous voice, a natural gravity that made even me, as a child, aware of the importance of the occasion. It is true that Churchill was the better speaker; he had wonderful ability to change the tone of his voice from grave to humorous, and an actor’s gift for the long, pregnant pause that made you wonder whether he was going to finish the sentence at all (Laurence Olivier and Ralph Richardson employed the same trick on the stage to keep the audience in suspense), and of course he had an energy, the gift of Shakespearean eloquence, and a taste for historical allusions that came close to poetry, sweeping his listeners along with him as the tide carries away a small boat, even those who did not agree with him politically.

All the same, Neville Chamberlain’s voice, if not his words, remains etched in my memory seventy-five years later. Chamberlain has been accused of self-pity in his speech telling us that we were at war, but I cannot find that, reading it or listening to it again. On the contrary it seems to me moving and dignified. One might wish for a hint of anger, a touch of fire, but those are just the qualities that Chamberlain himself lacked; he had none of Churchill’s theatricality and hid his emotions rather than displaying them. Quietly and briefly, he told us the facts, but did not disguise his sadness or his personal disappointment.

As if in a play the prime minister’s speech was followed almost immediately by a moment of high drama as air raid sirens began to wail all over London. With reluctance we trooped down to the basement, carrying our gas masks, and sat down on a bench in front of shelves piled high with my father’s bottles of wine. Nanny held my hand tightly, the dog lay at our feet, my mother chatted away cheerfully. The Hungarian cook kneaded her handkerchief, or perhaps her rosary, poor woman—there was a faint possibility that she might become “an enemy alien,” in which case she would be interned for the duration of the war or deported home, but luckily for her Hungary did not join the war until December 1941, by which time my father had duly arranged, no doubt through Brendan Bracken, to somehow get her British papers. How she managed to communicate with Nanny and my mother or they with her was a mystery, but given the ingredients of a dish, however foreign it might be to her, she could cook it.

I do not remember being particularly afraid, since for children excitement often cancels out fear, but in any event nothing happened—the cataclysm predicted by H. G. Wells failed to take place. After a few minutes the all clear sounded—it emerged, as I discovered many years later, that the alarm had been set off not by German bombers but by a private light plane carrying a few wealthy golfers home from a weekend in Le Touquet—and we went back upstairs for lunch.

“Well, that wasn’t too bad, darling,” my mother said.

To which my father answered darkly, “You will see how wrong you are.”