General Gamelin and General Lord Gort.

General Gamelin and General Lord Gort.

ALTHOUGH NOBODY COULD have known it at the time, the next eight months would become known as “the phoney war,” a phrase coined by Senator William Borah of Idaho, characterized by timidity, inaction, and lethargy on the part of the Allies, and a puzzling hesitation on the part of the Germans. “Is Hitler trying to bore us into peace?” quipped the American-born Henry “Chips” Channon, member of Parliament, wit, social climber extraordinaire, and, as acknowledged after his death, infamous diarist. Of course it was not “phoney” for the Poles, who were defeated in an eight-week campaign that gave birth to the term “blitzkrieg,” a lightning war of movement spearheaded by a few elite “panzer divisions” consisting of tanks, motorized infantry, and artillery, backed up by the ubiquitous Ju 87 “Stuka” dive-bombers and followed by the slower-moving mass of regular infantry divisions. These tactics were novel and controversial in the German Army (as well as stoutly resisted by the more conservative German generals), and virtually ignored by the French and British armies.

In other respects too, the war was anything but “phoney” for Poland, which was brutally divided between Germany and its ally the Soviet Union, and altogether eliminated as a state. In the eastern part, seized by the Red Army, Soviet rule would be marked by such events as the notorious Katyn Forest Massacre, in the course of which over twenty thousand Polish officers, lawyers, landowners, and priests were executed by the NKVD (the acronym then for what later became known as the KGB). In the western part, Nazi political control was added to the rule of the German Army, which was already harsh. Poles were stripped of all rights; forced labor, expropriation, the execution of Polish intellectual and political leaders, and draconic “security measures” were undertaken immediately, following the policy foreordained by Hitler as early as 1923 when he wrote Mein Kampf, in which Poland was to be depopulated and turned into a German agricultural colony, farmed by slave labor. In no other occupied country save those parts of the Soviet Union that fell under German rule between 1941 and 1944 were the precepts of what the British historian Hugh Trevor-Roper later described with acid precision as “bestial Nordic nonsense” carried out with such thoroughness and severity.

For the three and a half million Polish Jews a far worse fate was envisaged. From the moment the SS crossed the frontier in the wake of the army, they carried out against Jews summary executions, random murders, and massacres, a policy of terror and repression soon to be followed by the more systematic operations of the Einsatzgruppen, or mobile killing squads, then “ghettoization” and the “Final Solution” of “extermination camps.”

For all practical purposes, Poland simply ceased to exist, just as Hitler had promised.

* * *

None of this was revealed to the public in Britain or France, though some of it seeped out thanks to the trickle of Polish soldiers, airmen, and sailors who had miraculously made their way to Paris and London in the wake of defeat (eventually over 200,000 Poles would fight in the British armed services). My father knew more about it than most people, since a stray Polish antiaircraft battery was sited near the London Films studio at Denham, and many Poles from the southern part of the country had a smattering of German—since that had been the common language of the old Austro-Hungarian Empire. My father spoke what was known as Miklosdeutsch, basic German with a strong Hungarian accent, which was enough for him to communicate with the Polish antiaircraft gunners, who were lonely out in the English countryside and at this point in the war had no German aircraft to shoot at. At the time Vincent was preparing the sketches for two of London Films’ most ambitious and expensive projects, The Thief of Baghdad* and Jungle Book, on both of which he was the art director, and from time to time he took a break from his work by walking over to visit the Polish gunners, who, whatever their problems, were not pressing him for set designs and production estimates. For the most part he sat next to their gun, sharing his Player’s Navy Cut cigarettes with them. Vincent had no special interest in Poland, but at least the gunners were familiar: Central Europeans, rather than the incomprehensible English, with their strange accents, their incomprehensible class differences, and their fondness for tea with milk and sugar at all hours of the day and night, like my mother and her parents.

Denham was about to play a larger role in our lives, since Alex, who took being “head of the family” very seriously and felt responsible for all of us, had decided to lease a nearby country house and move the whole Korda family there, still apparently convinced by his friend H. G. Wells’s belief that Hitler’s first move against Britain would be a colossal air attack on London. This move was stoutly opposed by my mother, a working stage actress who had no taste for country living, and by my uncle Zoltan’s wife, Joan, also an actress—each had met her future husband while playing small parts in Alex’s breakthrough English film, The Private Life of Henry VIII—in 1932. But Alex’s wishes were the equivalent of a command to his brothers. News of the impending move even percolated down to my six-year-old level, or rather made its way upstairs to “the nursery” where Nanny and I lived, and was the subject of many hushed, serious talks between Nanny Low and Nanny Parker, my cousin David’s nanny, as well as of frequent arguments between my father and mother.

Looking back on it with the hindsight of three-quarters of a century, it seems likely to me that Alex took the threat of what might happen more seriously than his brothers or their English wives—his name was on the Gestapo’s then secret list of those prominent British anti-Nazi political, financial, and cultural figures who were to be arrested and killed once the Germans occupied Britain, the so-called Black Book, or Sonderfahndungsliste-G.B., a tidy printed handbook like the pocket Guide Michelin, with the address of those listed neatly and carefully printed next to each name. It included not only Alex but such friends as H. G. Wells, Winston Churchill, Noël Coward, and the cartoonist David Low. (“My dear—the people one should have been seen dead with,” Rebecca West, who was also on the list, would telegraph Noël Coward, once the war was over and the list made public.) Others on this curiously selected list included Churchill’s son-in-law, the formerly Austrian-Jewish comedian and singer Vic Oliver, and the novelist Virginia Woolf, who would be dead by her own hand the following year. Already a famous movie director and producer, Alex had been in Budapest when Admiral Horthy’s Fascist troops took the city in 1919, and knew what to expect—he had only escaped from being executed in the White Terror that followed the overthrow of Béla Kun’s Communist regime by the energetic intervention of his first wife, the silent film star Maria Corda, and his brothers. However brutal Horthy’s actions had been when he seized power, German efficiency and Nazi zeal could certainly be counted on to make things much worse if the Germans invaded Britain. Harold Nicolson and his wife, Vita Sackville-West, were not the only couple to have obtained poison pills from their doctor just in case, “the bare bodkin,”† as they referred to them in their letters to each other.

In the meantime, the gardens, with their peacocks and topiary, and the luxurious furnishing of the manor house in Denham, which looked rather like one of my father’s film sets, were not making this enforced family exile more tolerable. At dinner the three brothers sat at one end of the dining room table arguing in Hungarian, while my auntie Merle (Oberon), just back from Hollywood, where she had been playing Cathy in Wuthering Heights, my mother, and my auntie Joan sat in silence at the other end. There was no love lost between Merle and her sisters-in-law, both of whom resented her rapid rise to stardom and her marriage to Alex. As for Auntie Merle herself, she was anxious to return to California as soon as possible, since Wuthering Heights had made her an international star. Every night my mother looked with longing toward London, expecting to see the fiery glow from H. G. Wells’s anticipated attack on London, and seeing nothing once again she moaned one night, “Oh, where is that wretched Göring!”

At one point, the atmosphere became so poisonous that my mother peed in her chair—the dining room chairs were upholstered in expensive moiré silver silk—and was too ashamed to get up after dinner. Alex, more sensitive than his brothers, noticed that she was still sitting there after the butler had cleared the table and everybody else had gone into the sitting room, and gently asked her what the matter was. Her answer did not shock Alex, nothing could do that, but it did apparently convince him that he had made a mistake. Within days Merle was on her way back to California by air, and the rest of us were on our way back to our homes.

The feeling of helplessness and confusion that briefly overcame the Korda family at Denham in the seven months of the phoney war was not unlike that which gripped almost everybody in the wake of the rapid German conquest of Poland, with the possible exception of the Germans themselves. Neville Chamberlain had been shamed into declaring war against Germany by the unexpected resolve of the House of Commons, and the French were bullied into following suit, but the old instinct of appeasement, the urge to negotiate an end to the war rather than fight it to the bitter end, had not yet been laid to rest, and soon resurfaced in Paris and London. The French, acting momentarily out of guilt, fulfilled their obligation to Poland by advancing a few miles into Germany around Saar, then returned to their lines, having achieved nothing except a few propaganda photographs of French soldiers standing underneath German street signs. RAF Bomber Command was strictly limited to dropping bundles of propaganda leaflets over Germany.

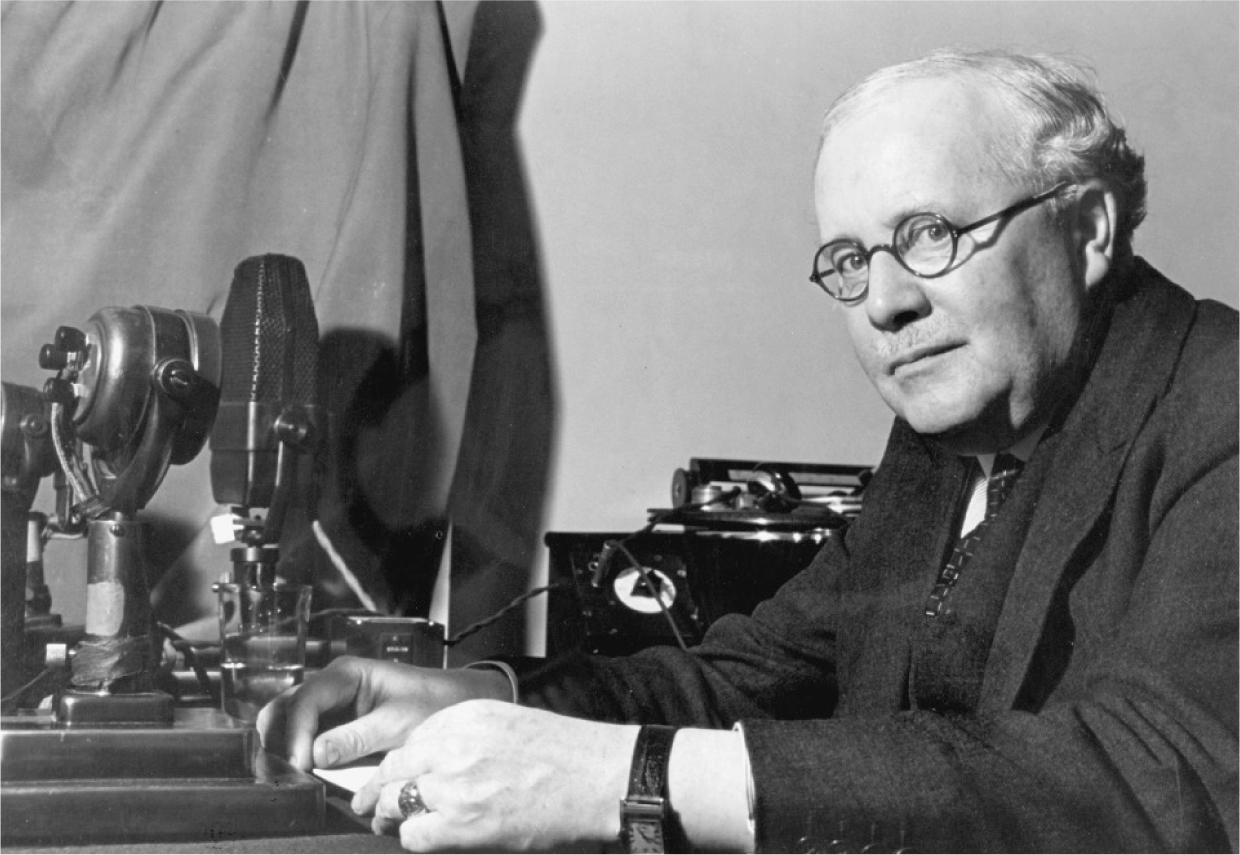

Sir Howard Kingsley Wood.

The spirit of appeasement lived on. In Britain, when it was suggested to Sir Howard Kingsley Wood, the secretary of state for air, that the Royal Air Force should drop incendiary bombs on the Black Forest and set it on fire (the Black Forest was then believed to contain a large number of hidden ammunition dumps), he protested indignantly, “Are you aware that is private property? The next thing, you will be asking me to bomb Essen!”

In fact the most warlike decision that Chamberlain made—and the one that would have the most drastic effect on the war—was to invite Winston Churchill to join the War Cabinet, and also to serve once again, as he had from 1911 to 1915, as first lord of the Admiralty (the civilian head of the Royal Navy, roughly equivalent to the American secretary of the navy). Chamberlain’s War Cabinet consisted of nine men, including the prime minister—probably too many, Lloyd George’s War Cabinet in World War One had only consisted of five—and placing Churchill in it was tantamount to putting a hawk in a cage full of doves.

It may or may not have been true that when Chamberlain offered Churchill the Admiralty the message was transmitted to all the Royal Navy’s ships, “WINSTON IS BACK.” The dean of all Churchill biographers and researchers, the late Sir Martin Gilbert, was unable to find the original signal, but felt that even if it was not true, it ought to have been, and so included it in volume one of The Churchill War Papers—like so much else about Churchill, fact and myth are superimposed and inseparable. It is not just that Churchill was a “bigger than life” personality even as a youth; he was also an indefatigable, prolific, and gifted writer, with a flair for the dramatic. When in an argument about the delay of “the Second Front” at the Tehran summit meeting in 1943, he was goaded by an angry Stalin, who said icily, “History will be the judge of this,” Churchill replied, “History will judge me kindly, for I intend to write it.”

That has proved to be true. Much of what we assume we know about the history of World War Two in fact derives from the six volumes of Churchill’s The Second World War, at once a history and a memoir, which not only won him the Nobel Prize in Literature in 1953, but stamped his view of what took place indelibly on what we know, or think we know, about the events, the people, and their motives during the period. Churchill achieved exactly what he set out to do—in the English-speaking world we still see that war largely through his eyes, particularly since his opponents Hitler and Mussolini did not live to write their memoirs, nor, among the Allies, did Roosevelt, while Stalin chose not to.

Churchill paints a dramatic scene of his return to the Admiralty in volume one of The Second World War:

So it was that I came again to the room I had quitted in pain and sorrow almost exactly a quarter of a century before, when Lord Fisher’s resignation had led to my removal from my post as First Lord and ruined irretrievably, as it proved, the important conception of forcing the Dardanelles. A few feet behind me, as I sat in my old chair, was the wooden map-case I had had fixed in 1911, and inside it still remained the chart of the North Sea on which each day . . . I had made the Naval Intelligence Branch record the movements and dispositions of the German High Seas Fleet. . . . Once again! So be it.

He rolled up the carpet, sent for his old octagonal table, gave orders to have a map room set up and staffed for him so that he could follow every naval development as signals came in, then got down to work. In his history of the war he makes the fact that Chamberlain offered him a place in both the War Cabinet and the Admiralty seem like a decision he welcomed, but in fact both his enemies, which then still included the majority of Conservative members of Parliament, as well as his closest supporters all thought that this had been an adroit political move of Chamberlain’s intended to keep Churchill so busy with naval affairs that he would not have time to make trouble in the War Cabinet.

If so, this was a battle lost before it even began. Churchill’s experience of war, his phenomenal energy, his curiosity, his remarkable memory, his ability to stay up until the small hours of the morning sipping whiskey while he dictated immensely long and well-informed papers on every aspect of the war all combined, together with his personality and his gift for what we would now call “public relations,” to make him the dominant member of the War Cabinet, overshadowing everyone, including the prime minister. Unlike other members of the War Cabinet, he brought with him his own corps of advisers and specialists, including his supremely self-confident and abrasive friend and scientific adviser Professor Frederick Lindemann of Oxford, referred to not necessarily with affection by those around Churchill as “the Prof.” As a result Churchill often seemed better informed than the other service ministers, or even than the prime minister himself, whose interest in military affairs was in any case limited.

The undercurrent of hostility toward Churchill was fierce, strongest of all in his own party, hence the rumor that the first thing he did when he reached his desk at the Admiralty was to send for a bottle of whiskey, although that is contradicted by the accounts of everyone who was present. Rumors that Churchill was a drunk had been around for many years (appearing nowhere more frequently than in the Nazi press in Germany), but in fact he was that rarest of men, a well-functioning, even hyper-functioning alcoholic. He drank a weak whiskey and soda (without ice, of course) at frequent moments during the day when most other people would have asked for a cup of tea or coffee, while his meals were accompanied by vintage Pol Roger champagne and followed by brandy. Churchill would shock Eleanor Roosevelt during his first stay at the White House when she learned that he had told the White House butler to make sure he received a large glass of sherry every morning on his breakfast tray, but he was never seen to be actually drunk—he simply needed a certain amount of alcohol to keep him going through his long days and longer nights, and was a good judge of how much he needed and when to stop. As he would one day in old age put it himself, “I have taken more out of alcohol than alcohol has taken out of me.”

A man more different from the abstemious and stiff Neville Chamberlain would be hard to find than the half-American grandson of a duke, a colorful military adventurer who had participated in the last great cavalry charge of the British Army at the Battle of Omdurman in 1898, and who wrote of his experience under fire in Cuba, “Nothing in life is so exhilarating as to be shot at without results.”

Churchill’s feelings about Chamberlain were ambivalent. On the one hand Churchill respected him as the leader of the Conservative Party and as a shrewd politician; on the other he had been fighting vigorously against Chamberlain’s policy of appeasement since 1933, both in and out of Parliament. Once, when a cabinet minister was speaking about a murderous riot between Arabs and Jews, and ended his speech by expressing his solemn regret that this incident should have occurred of all places “in Bethlehem, birthplace of the Prince of Peace,” Churchill could be heard throughout the chamber asking the member sitting beside him in a stage whisper, “But have we not always been given to understand that Neville was born in Birmingham?”

Making fun of Chamberlain was easy enough, for he had no discernible sense of humor himself, and was a perfect target, with his lean scarecrow figure and solemn face—although he was actually a ruthless and unforgiving politician, with complete control over his own party. Harold Nicolson, the diarist and at that time member of Parliament, described him unforgettably as looking like “the Secretary of a firm of undertakers reading the minutes of the last meeting,” but Churchill’s speeches against appeasement and in favor of rearmament had drawn blood over the years. They were brilliant, well informed, deeply wounding to Chamberlain and unrelenting. Of the Munich agreement Churchill said, “£1 was demanded at the pistol’s point. When it was given, £2 were demanded at the pistol’s point. Finally, the dictator agreed to take £1 17s. 6d, and the rest in promises of good will for the future. . . .” The fact that Churchill had been proved right in the end did nothing to endear him to most of his fellow Conservatives.

None of that is to say that Churchill was always right. A lifelong Francophile, he gravely overrated the French Army, and therefore failed to appreciate the degree to which it had become a mere façade, weakened by the political and class divisions in France between the wars, hollowed by the enormous sacrifices France had made in World War One, and led by senior officers who distrusted their own politicians and clung to outdated strategies. Although more than three million men strong in France alone,‡ the French Army was in reality a shadow of its former self, but that shadow was still softened by the glory of its past.

Luckily for Churchill, the Royal Navy in 1939 was still the world’s largest and most powerful—here, at least, was an area in which Germany could not compete on equal terms, and the war on the sea began at once, albeit at a fairly low level, and not without mishaps. Whatever the deficiencies and doubts of the other services, the Royal Navy at least was ready for war. “By the 27th September the Royal Navy . . . had moved to France, without the loss of a single life, 152,031 army personnel, 9,392 air force personnel, 21,424 army vehicles [and] 36,000 tons of ammunition,” the first installment of “the British Expeditionary Force,” without any interference from German surface ships, submarines, or mines, a remarkable testament to the Royal Navy’s professionalism, skill at improvisation, and control of the sea. When the British thought of their strength, the one thing in which they reposed trust was “the great, gray ships” of the Royal Navy, and in 1939 they were not wrong.

Churchill spoke for that strength, and from the very first minute that he took office on September 3, 1939, he devoted himself to the navy’s needs in detail, with the easy grace of an opera singer taking on a familiar role from his past repertoire. On his first day in office the famous crisp Churchillian notes began to go out at once, signifying that he was back in charge, and causing necks bearing gold-braided caps to snap to attention all over the world—

TO DIRECTOR OF NAVAL INTELLIGENCE:

3 September 1939

Let me have a statement of the German U-boat force, actual and prospective, for the next five months. Please distinguish between ocean-going and small-size U-boats. Give the estimated radius of action in days and miles in each case.

TO THE FOURTH SEA LORD:

3 September 1939

Please let me know the number of rifles in the possession of the Navy both afloat and ashore. . . .

TO THE DEPUTY CHIEF OF THE NAVAL STAFF:

3 September 1939

Kindly let me know the escorts for the big convoy to the Mediterranean (a) from England to Gibraltar, and (b) through the Mediterranean. I understand these escorts are only against U-boat attack.

Officers at every level scrambled to answer the first lord’s questions, and assemble the reams of information that he required, and also learned that delay or imprecision would be instantly rebuked. No item was too small or too large in scope to escape Churchill’s attention.

Meanwhile, a torrent of congratulatory letters and telegrams flooded in from HRH the Duke of Windsor to Lady Blood, the wife of Churchill’s old commander in the Malakand Field Force, in which Churchill had served as a second lieutenant in 1897, and he struggled to answer them all.

The most important of them was a letter from President Roosevelt, congratulating “My dear Churchill” on having completed the fourth and final volume of his biography of the Duke of Marlborough, his great ancestor, before the war broke out, and inviting him to “keep me in touch personally,” thus beginning the longest, the most intimate, and surely the most productive secret correspondence in history, consisting of over seventeen hundred letters between them, almost one a day until Roosevelt’s death, dealing with every aspect of the war.

Neither the prime minister himself—whose speeches in the House of Commons were “as dull as ditchwater,” in the words of Harold Nicolson—nor Foreign Secretary Lord Halifax could match the first lord’s zeal for combat, persistence, oratorical skill, or formidable powers of argument. He dominated the other members of the War Cabinet, including the other service minsters. Sir Kingsley Wood, secretary of state for air, had been a successful and innovative postmaster general, described unkindly but accurately by Roy Jenkins as “the legal panjandrum of industrial insurance,” and Leslie Hore-Belisha, secretary of state for war, was a former minister of transport, in which office he had created a national speed limit, and instituted the familiar “Belisha beacons” and “Zebra crossings” that have protected pedestrians in the United Kingdom as they cross the road ever since.

Hore-Belisha, who had been in charge of the army since 1937 when Chamberlain appointed him to reorganize and modernize the British Army—always referred to as “the Cinderella of the Armed Services,” since the bulk of defense spending went to the Royal Navy and the Royal Air Force—might have been a rival to Churchill, but he was instead a good example of Chamberlain’s blind confidence in his own judgment over other people’s advice. Hore-Belisha loved publicity and got lots of it, he was flashy, impatient, obsequious to those above him and rude to those below, and he was also, in an age when that still mattered a great deal more to many people, a Jew. No choice for secretary of state for war could have been better calculated to enrage the senior officers of the British Army, who, despite their differences, clung to a man to exactly those things that Hore-Belisha wanted to change or reform, the abolition of the cross strap on the Sam Browne belt for officers and warrant officers being one of the most deeply resented.

In addition to Hore-Belisha’s other problems with his generals, he had the further disadvantage of possessing an éminence grise in the person of Captain B. H. Liddell Hart, the Times military correspondent and controversial author of at least twenty-five books on warfare. Liddell Hart was a proselytizer for what he called “indirect warfare,” by which he meant that the British Army should avoid the frontal attacks that had made the 1914–1918 war so costly in lives. He also believed strongly that Britain should never again field “a Continental army,” as it had in the last war—that its contribution to its Continental allies should consist of a strong navy and air force, leaving land warfare to others. This coincided with Chamberlain’s own view on the subject—nobody in his right mind wanted to repeat the 1914–1918 war—but as Hitler rearmed Germany and stripped away one French ally after another, it became apparent that Britain could not expect the French to take on the whole burden of land warfare, and that the British Army would have to be drastically enlarged and reequipped in haste if it was to be of any help to France.

Liddell Hart was one of the small band of visionaries who saw the tank as opening up a new kind of warfare, in which fast-moving columns of armored vehicles would range far behind the enemy front line wreaking havoc on his lines of communications. In this respect he was a prophet without honor in his own country, like Major-General J. F. C. Fuller, CB, CBE, DSO, and Colonel Charles de Gaulle in France, whose book on armored warfare, Vers l’Armée de Métier, sold fewer than seven hundred copies in France (it was either ignored or ridiculed by his superior officers), but over seven thousand in Germany, where it became the bible of almost every one of the future German panzer generals and was read aloud in German to Hitler.

Although the tank had been invented in Britain early in World War One—it was designed to cross over enemy trenches, hence the curious elongated and rhomboid shape of early tanks—the British Army did not follow up on it with any energy, partly for lack of funds, partly because if the government’s policy was to avoid at all costs “a Continental war” it would not need tanks. All three of these visionaries developed their theory of armored warfare before the appropriate vehicles to carry it out had been produced—they had to imagine not only the tactics but also the tanks.

In the event, British tank development was not only “too little, too late,” but gave the British Army two different kinds of tank, neither of which was appropriate to Liddell Hart’s ideas, first a heavy, slow-moving “infantry tank,” intended to support infantry, then a “cruiser tank,” which was faster, but too lightly armored and armed, and mechanically unreliable. The French Army did much better—it had, in fact, more and better tanks than the Germans in 1939, let alone the British, but they were organized to support infantry attacks, rather than to play the role Liddell Hart, J. F. C. Fuller, and de Gaulle had envisaged.

The early models of German tanks were small and lightly armed, but Germany had several advantages over its enemies. In the first place, German tanks had been tried out in combat during the Spanish Civil War only three years before and important lessons had been learned there. In the second, Hitler was susceptible to new and radical ideas and had a special interest in motor vehicles of all kinds, hence his enthusiasm for Dr. Ferdinand Porsche’s prototype air-cooled Kraft durch Freude Wagen, intended to be sold on the installment plan to members of the Nazi Party’s “Strength through Joy” organization,§ which eventually became known as the Volkswagen, and then as the beloved postwar “Beetle.” Finally, the younger German generals who had taken the writings of Hart, Fuller, and de Gaulle more seriously than they were taken in their own country evolved from them a strategy that would become known, for the most part outside Germany, as blitzkrieg, or lightning war.

The man who pulled all these theories together into practical form was Major General Heinz Guderian, who also distilled them into a book, Achtung—Panzer!, which attracted the attention of Hitler, though regrettably not that of anybody in France or Britain. In it the new German method of attack was clearly described, had anyone outside Germany cared to read it.

Something of une chapelle, the French term for a group of officers drawing inspiration from their common belief in the theories of one charismatic, innovative, visionary officer, like that which formed around Ferdinand Foch in the French War College in 1911, had also formed around Guderian as early as 1927. Guderian had been trained as a signals officer rather than a cavalryman, and therefore approached the development of tanks from a different, more practical point of view than was the case in the postwar French or British Army. He did not assume that the tank was “merely an armoured, mechanical horse,” in the words of one British military manual.

First of all he understood at once that the tank commander must be able to communicate with his crew despite the noise of battle (not to speak of the ever-present mechanical noise of the engine) by means of an intercom system, and that each tank must also have a radio and a trained radio operator so that the tanks could communicate with each other, receive orders, and report artillery coordinates.

Guderian, whose personality was described by his fellow generals as “bull-like” (they meant that in praise), set out from the very beginning with the idea that each armored division should be like a miniature army and consist of at least two brigades of heavy and medium tanks, as well as two brigades of motorized infantry—tanks could take ground, he realized, but they could not hold it; therefore they must work in tandem with infantry that could follow them in armored vehicles (or “armored personnel carriers,” as they are now called), and these troops must be specially trained to work closely with “armored fighting vehicles.”

What is more, the armored division Guderian had in mind must be self-supporting, which meant it must also include motor-drawn artillery and antiaircraft guns, a unit of armored, fast-moving reconnaissance vehicles, pioneers (or engineers) in armored half-tracks who could repair or build bridges and demolish antitank obstacles on the spot, and a motorized repair unit with heavy vehicles that could tow damaged tanks or tanks with a serious mechanical failure out of the way.

The critical factor was to keep the tanks moving forward at all costs, never to let them be halted, which would transform them into targets for enemy artillery or aircraft. Radio communications would have to be sophisticated enough to let tank commanders call in artillery fire when and where it was needed (and eventually to call in support from dive-bombers, which Guderian’s imagination thought up before they existed) to destroy or demoralize enemy forces that might hold up or slow down the tanks—the vital element was speed. His model was the great Thomas J. “Stonewall” Jackson, whose Shenandoah Valley Campaign in 1862 provided the inspiration for German armored warfare tacticians.

It should not be imagined that all this came about quickly or without determined opposition on the part of senior generals of “the old school,” few of whom were admirers of Stonewall Jackson or students of the Battle of Port Republic in 1862. Guderian had no previous experience with tanks, but when he was transferred as a staff officer in 1922 to the “Motor Transport Troops,” itself then a small and unglamorous cog in the Truppenamt, the shadow general staff of the tiny German Army of 100,000 men, which was all Germany was allowed under the terms of the Treaty of Versailles, Guderian immediately looked beyond the humdrum task of transporting troops by motor vehicles to the battlefield to the development of a secret armored force. The early German tanks were tested in the Soviet Union—the two “outcast” nations, Germany and Bolshevik Russia, found it expedient to collaborate on military experiments out of the sight of Allied observers—but it wasn’t until 1927 that Guderian actually got to sit in a real tank and drive it, while on a visit to Sweden. Most of his “exercises” were carried out with dummy tanks, trucks, and motorcycles, and it wasn’t until 1934 that his concept received the unequivocal blessing of the new Reichskanzler, Adolf Hitler, who witnessed “a demonstration of motorized troops” at Kummersdorf “and exclaimed, ‘That’s what I need, that’s what I want to have!’ ”

This enthusiasm was not shared by most of the senior generals of the German Army. Like their opposite numbers in the British and French armies, they were reluctant to accept radical new ideas. In the British and French armies this view was of course strengthened by the fact that they had won the last war, admittedly by the narrowest of margins, so there seemed no good reason to reinvent what had worked. In the German Army, the view of the most senior generals was that they had almost won the last war at the time of the Ludendorff offensive in March 1918 only to be “stabbed in the back” by Socialists, Communists, and Jews on the home front. What was needed was diplomacy that would limit a future war to one front, a firm hand at home against the left and the trades unions, and renewed conscription that would build the German Army back to its former strength rather than faddish and expensive new ideas about how to wage war.

There were exceptions, one of the most important being the brilliantly talented Erich von Manstein, nephew of Field Marshal and President von Hindenburg, who was at once by birth and marriage a well-connected member of the army’s social elite and an admirer of Hitler’s (though both he and Guderian would eventually fall out of favor with him). The idea of armored warfare also attracted a significant number of field rank officers, among them such famous future panzer generals as Erwin Rommel and Hasso von Manteuffel, but controversy about the importance and the use of tanks would continue to bedevil the German Army until the very end of the war.

In 1935 Guderian was made commander of the new 2nd Panzer Division, one of three newly created panzer divisions, and began to put into practice his theories about armored warfare, at the heart of which was his pithy comment “Nicht kleckern, sondern klotzen!” (Smash them, don’t spatter them!), which became so well known that Hitler adopted it for his own use, and which Guderian expanded later into a compact, but complete, description of armored warfare: “Man schlägt jemanden mit der Faust und nicht mit gespreitzen Fingern.” (You hit somebody with your fist, not with your fingers spread.) In other words, tanks must not be spread about in “penny packets,” in the words of future Field Marshal Montgomery, but concentrated in a single, powerful thrust. To this he added his three indispensible requirements for successful tank combat: “Suitable terrain, surprise, and mass attack in the necessary breadth and depth.”

Promoted to lieutenant general, Guderian commanded the XIX Corps in the attack on Poland, and demonstrated the correctness of his theories in combat, but although neutral (mostly American) journalists called the war in Poland a blitzkrieg, conjuring up pictures of masses of fast-moving tanks against cavalry, the German Army in fact achieved victory in Poland by superior numbers (over 1,500,000 men against 950,000) and vastly superior weapons, and fought a relatively conventional war against an enemy that was not yet fully mobilized. The panzer divisions were largely used in support of the German infantry—just the opposite of how Guderian believed they should be used—and although the presence of tank formations impressed neutral journalists, they accomplished nothing decisive.

Highland troops on their way to France, 1939.

All the same, the abilities of the tank to travel substantial distances at a relatively high speed and to influence the outcome of a battle were both proved—as was the ability to keep the tanks supplied with fuel and to repair them in the field, as well as the use of the Ju 87 Stuka dive-bomber in the role of “flying artillery to support the tanks.” The number of panzer divisions was increased to ten for the attack against France and the Low Countries, which was planned for October 1939, only a month after the Polish surrender.

_________________________

* He would win an Academy Award in 1940 for the art direction of The Thief of Baghdad.

† For who would bear the whips and scorns of time,

The oppressor’s wrong, the proud man’s contumely . . .

When he himself might his quietus make

With a bare bodkin?

—WILLIAM SHAKESPEARE, Hamlet, act 3, scene 1

‡ It must be kept in mind that France was then still a worldwide empire. There was a French commander in the Levant (Syria and Lebanon), another in North Africa (Algeria and Morocco), and yet another in the Far East (French Indochina), not to speak of other, sub-Saharan African colonies, and Pacific and Caribbean islands. All of them reported to the commander in chief General Maurice Gamelin in Paris.

§ Not all of Dr. Porsche’s creations were as pacific in intention as the Volkswagen. A favorite of Hitler’s, Porsche was deeply involved in the design of later German tanks, including the Panther and the Tiger (the latter arguably the most formidable tank of World War Two), and after the German defeat spent some time in prison accused of being a war criminal.