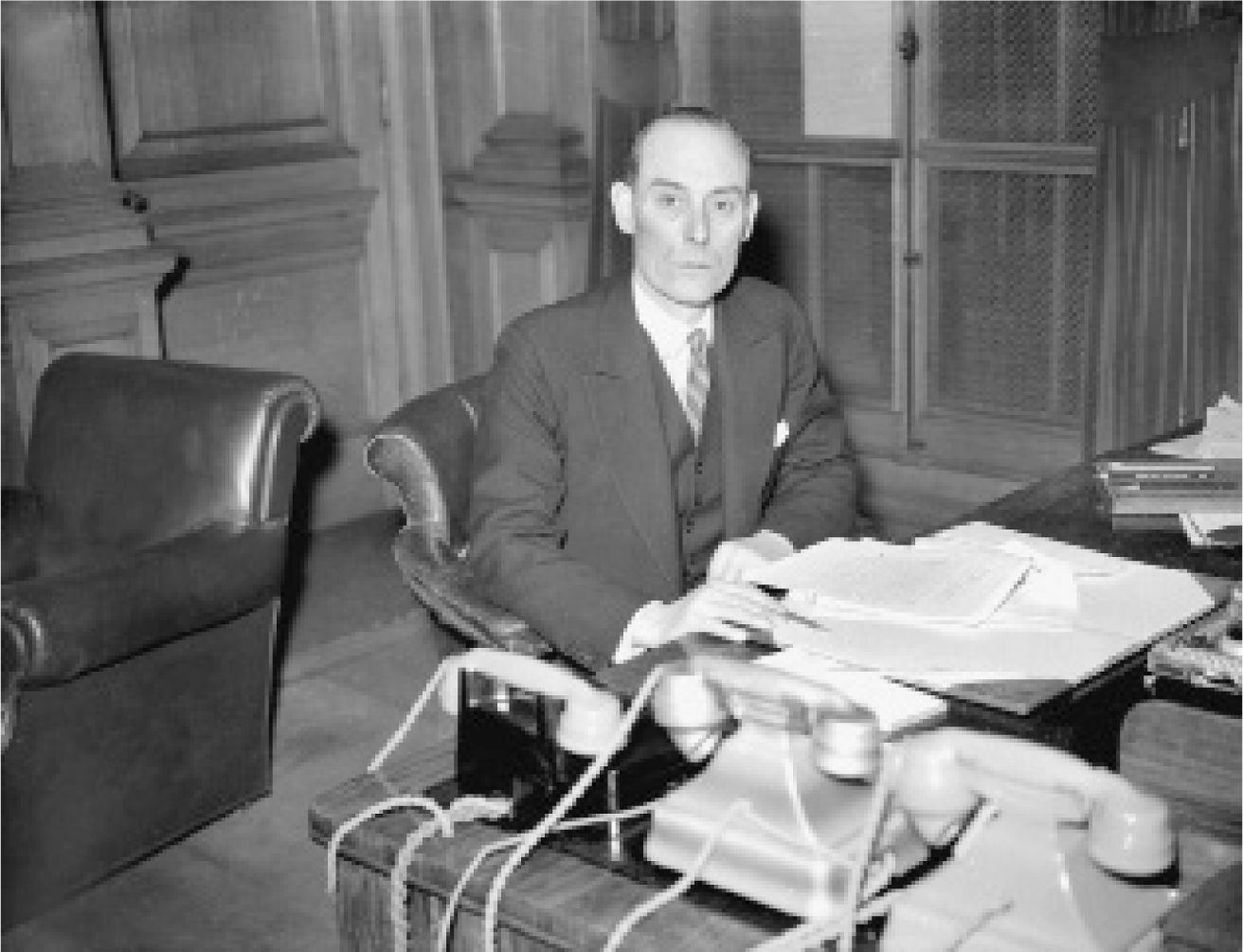

David Lloyd George and Leo Amery.

David Lloyd George and Leo Amery.

ALREADY BY MID-APRIL of 1940 it was apparent to many people—certainly to members of the House of Commons—that the battle for Norway had gone badly wrong. British naval successes, though considerable, could not disguise the fact that Hitler had taken the Allies, by surprise with a well-planned, swift, and ruthless attack, and that there appeared to be no Allied strategy in place for victory. Initial euphoria that Britain was at last in action gave way to “a general feeling of apprehension,” and to questions in the House even from loyal Conservatives. It was clear, to those in the know at least, that a major political crisis could only be prevented by news of a victory in Norway. It was not yet a political earthquake, merely a tremor, but it set off alarms and rumors.

Even Churchill, speaking to the House on the fighting in Norway, failed to strike the right note. Harold Nicolson, a friend and admirer, notes in his diary, “To the House. It is packed. Winston comes in. . . . When he rises to speak it is obvious that he is very tired. He starts off by giving an imitation of himself making a speech. . . . I have seldom seen him to less advantage.” Others noted that Prime Minister Chamberlain seemed to betray a certain satisfaction at Churchill’s poor performance. There was speculation that Churchill was “too old” for the post of first lord of the Admiralty (he was sixty-six at the time, five years younger than Chamberlain), and even talk that former Prime Minister David Lloyd George, Chamberlain’s nemesis, might be a better choice for prime minister than either of them, although he was seventy-seven,* and would very likely not have been acceptable to the king.

Even at his least effective, Churchill’s speeches to the House contrasted sharply with the short and funereal statements of the prime minister. Brendan Bracken referred to Chamberlain as “the Coroner,” and Harold Nicolson vividly drew the contrast between the prime minister and the first lord of the Admiralty seated side by side together on the front bench, one “dressed [as if] in deep mourning,” the other “looking like the Chinese god of plenty.”

Never forgetting that Churchill was a potential rival, or perhaps under the illusion that the best way to control him was to keep him in sight, Chamberlain took him to a meeting of the Supreme War Council in Paris presided over by Paul Reynaud, the new French premier, with results that disappointed them both. The French did not disguise their reluctance to launch “Royal Marine,” Churchill’s plan to place mines in the Rhine and float them downstream to disrupt German river traffic; moreover, still concerned about Paris, they continued to oppose bombing the Ruhr, or anywhere else for that matter. Even at this late date Belgium continued to follow a policy not unlike that of the ostrich that sticks its head in the sand when confronted by danger, so a preemptive move forward into Belgium was still ruled out. Though rather late in the day, the French proposed that neither of the Allies should seek peace terms without the consent of the other, something that one would have thought had been implicit from the beginning.

Neither Chamberlain nor Churchill appears to have been aware of something that le tout Paris had known for ages—the feud between Edouard Daladier, the former prime minister and now defense minister, and Paul Reynaud was not just a question of policy but also une histoire de femme. Daladier’s mistress the Marquise de Crussol,† a daughter of the wealthy owner of France’s most important sardine cannery, was the rival and mortal enemy of Reynaud’s mistress the Comtesse de Portes, daughter of a family of shipowners, both of them bourgeoises who had married into the nobility, and both forceful personalities whom it was unwise to cross. The two ladies fought out their rivalry not only in terms of fashion and haute couture but also in politics. Churchill came quickly to think of Reynaud as a kindred spirit, certainly preferable to Daladier, but had no idea that Hélène de Portes was bitterly Anglophobic and opposed to the war, if indeed he even knew of her existence. It was due to the influence of Mme de Portes that Reynaud had just reshuffled his cabinet to get rid of the more determined members in favor of those who saw no gain in France’s fighting England’s war. These were deeper waters than Chamberlain, Halifax, and Churchill knew—none of them was what one might describe as “a lady’s man,” and it would surely have surprised them to know that France’s defense minister and its premier were each receiving political advice from their respective mistress, or revealing military secrets as pillow talk.

In any case, nothing the French could do at that point would save Norway. By the first week of May it was evident that the south of Norway was lost, and that it would be difficult, if not impossible, to hold on to the northern part in view of German control of the air. What little was known to the member of the House of Commons was a story of muddle, individual heroism, poor planning, and lack of even the most basic military equipment. Although the prime minister had asked Churchill, as the senior service minister, to preside over the “Military Coordination Committee,” nothing could disguise the confusion and lack of leadership at the top. Churchill himself aptly complained about “the formlessness of our system,” which resulted in there being “six Chiefs [and Deputy Chiefs] of the Staff, three Ministers, and General Ismay, who all have a voice in Norwegian operations,” with nobody able to impose his will upon these layers of authority except the prime minister himself, who neither wished nor was able to. Churchill, hard pressed by the demands of the navy, found himself obliged to ask the prime minister to take over “the day-to-day management of the Military Coordination Committee,” and it was not until May 1 that Churchill was finally given control over the chiefs of staff and in effect, if not in title, made minister of defence.

Sir Horace Wilson and Chamberlain.

Little blame for what had gone wrong in Norway was aimed at Churchill, if only because the navy had performed brilliantly, and because the person who had tried the hardest to produce a more rational system was Churchill. Blame attached itself instead, however reluctantly among many members, to Chamberlain himself and to those closest to him, particularly the arch appeasers Sir Samuel Hoare, the lord privy seal, Sir John Simon, the chancellor of the exchequer, and Chamberlain’s adviser and backstairs strategist Sir Horace Wilson,‡ the most unrepentant appeaser of them all. Chamberlain, hitherto a supremely confident politician, seems to have had no forewarning of what was in store for him—after all, he had always managed to master the House of Commons, and he had a majority of over two hundred, making his position as prime minister virtually unassailable.

Nobody expected that the rumblings of discontent would turn into a roar on May 7. The opposition had asked for a debate on the Norwegian situation, but as soon as the prime minister rose to speak there were catcalls and shouts of “Missed the bus!” and it was clear that the mood of the House was angry, hostile, and confused over events in Norway. In the face of it, Chamberlain made a “feeble” speech, followed by several more from both sides of the aisle that failed to draw blood, but the session might have ended without much damage to Chamberlain had it not been for the intervention of Admiral of the Fleet Sir Roger Keyes, Conservative member for Portsmouth North since 1934, a friend of Winston Churchill’s, and a controversial naval hero of the First World War. Keyes commanded instant attention by appearing in his uniform as an admiral of the fleet, with six rows of medal ribbons glittering on his chest, in a rage about what he took as an insult to the Royal Navy by a Labour member, J. C. Wedgewood, something of a war hero himself. However, Keyes had a more important and personal ax to grind—he had proposed to lead a fleet of superannuated battleships into the Trondheim Fjord to recapture the city and prevent the Germans from taking central Norway, but the chiefs of staff had declined to accept his offer, a decision against which Keyes had protested with a series of long, angry letters of protest, all of which Churchill had tactfully deflected with what was for him unusual patience. Churchill’s own caution about Keyes’s scheme was understandable, since on paper it looked very much like the Dardanelles, in which Keyes had played a vigorous part. Keyes went on to give the House his side of that story and from there to make a long, slashing, well-informed, and “absolutely devastating” attack on the government.

Admiral Roger Keyes, center.

Although not a great speaker, Keyes rose to the occasion—he had sought the help of Harold Macmillan, a future Conservative prime minister, in preparing his speech and his blunt, forceful delivery and naval expertise caught the mood of the House. There was a “great gasp of astonishment” at his frank assessment of the muddle at the top (exonerating Churchill), ending with a damning statement, “One hundred and forty years ago, Nelson said, ‘I am of the opinion that the boldest measures are the safest,’ and that still holds good today.” Keyes sat down to “thunderous applause” from both sides of the House. (It is almost impossible to go wrong by quoting Admiral Nelson in Parliament in time of war.)

He was followed by Leo Amery, one of only four Conservative members who had remained seated in protest when Chamberlain announced that he was flying to Munich to meet with Hitler at the height of the Czech crisis in 1938,§ and who despite a diminutive stature had a formidable mind. Half Hungarian-Jewish, he spoke seven languages fluently, and had served as first lord of the Admiralty and as colonial secretary—even to die-hard supporters of the prime minister he commanded respect. Amery too was normally by no means a great orator, but on this occasion “his implacable sentences gave the impression of volleys fired into sandbags,” in the words of Edward Spears, speaking “as if he were hurling stones as large as himself” to a “still, strained House,” and rising to one of the most damning perorations in the history of British politics:

Somehow or other we must get into this Government men who can match our enemies in fighting spirit, in daring, in resolution and in thirst for victory. . . . We are fighting today for our life, for our liberty, for our all; we cannot go on being led as we are. I have quoted certain words of Oliver Cromwell. I will quote certain other words. I do it with great reluctance, because I am speaking of those who are old friends and associates of mine, but they are words which, I think, are applicable to the present situation. This is what Cromwell said to the Long Parliament when he thought it was no longer fit to conduct the affairs of the nation. “You have sat too long here for any good you have been doing. Depart, I say, and let us have done with you. In the name of God, go.”

The king and queen; on the right, Herbert Morrison.

Even as David Margesson, the chief whip, sought to rally the party faithful to support the prime minister, the impact of these words seemed to wound Chamberlain physically, as if the words had indeed been stones hurled at him. Chamberlain’s greatest failing was his vanity—vanity that had been ratified by a long record of success and a brief, though intense, period of adulation and increased by his insatiable appetite for flattery—but it must by now have been clear to him that he could no longer dominate the House, or even his own party, that he had been fatally damaged, not by the opposition—after all, as Winston Churchill once said, “The business of His Majesty’s Opposition is to oppose”—but by members of his own party. By the end of the first day of the debate, as members drifted off to dinner, it was apparent to almost everyone that the government was doomed without a major reconstruction. A mere “reshuffle” of ministers would not save it, and Chamberlain seems to have reached that conclusion himself.

Captain David Margesson.

The debate the next day, on May 8, got off to a rocky start for the government, even the normally supportive newspapers like the Times were critical of Chamberlain’s speech, while the tabloids and left-wing newspapers were staunchly critical. For a man who had always had a good press, it was a rude awakening. Worse was to follow.

Herbert Morrison, speaking for Labour, in Clement Attlee’s absence owing to illness, rose to make it brutally clear that the debate must be followed by a vote of censure. “I cannot forget,” Morrison said, speaking of the prime minister, the chancellor of the exchequer, and the secretary of state for air, “that in relation to the conduct of British foreign policy between 1931 and 1939, they were consistently and persistently wrong. . . . I have the genuine apprehension that if these men remain in office, we run a grave risk of losing this war.” This was an attack aimed directly at Chamberlain, and more important a warning that Labour might not serve under him if he should call for a coalition or “national” government, as some were beginning to suggest.

Chamberlain now made the mistake that would cost him his office. Rather than standing on his dignity, he let his feelings show. Smarting from this personal attack, he rose to welcome a division for a vote of confidence, and then added, “I do not seek to evade criticism, but I say this to my friends in the House—and I have friends in the House—no Government can prosecute a war efficiently unless it has public and Parliamentary support. . . . I call on my friends to support me tonight.”

Harold Nicolson noted that Chamberlain spoke the word “friends” with “a leer of triumph,” but in fact he could hardly have made a worse mistake than by emphasizing his anger about the personal attack on him in the middle of a debate about the conduct of the war, a fatal error of wounded vanity that shocked even the prime minister’s own supporters. Chamberlain might as well have put his own head on the block to be chopped off.

Lloyd George had been Chamberlain’s bitterest enemy since they had clashed during World War One, and when he rose to speak the House fell silent, as if they were about to watch an execution. With his lion-like mane of white hair and his piercing eyes, “the Welsh Wizard” Lloyd George had dominated British politics for nearly five decades. He was old now, and somewhat discredited by the greed and unscrupulous political dexterity with which he had clung to power after the First World War, by such scandals as the sale of titles for contributions, and by his reputation for relentless womanizing, but he had served as one of the most formidable war leaders in British history, as well as the innovator of much of the modern British welfare state—perhaps no one man was ever responsible for so much social legislation and so many radical changes in British life, or made such daring and far-reaching decisions in war and at the peace table after it. Perhaps no man before or since has ever had such absolute command of Parliament—even so great a speaker as Churchill was in awe of Lloyd George’s speeches.

The old man had been waiting for many years to take his revenge on Chamberlain, but with the skill of a master politician and spellbinding orator he took his time about it, carefully mentioning every failure of the government with the precision of a man who had been a great wartime prime minister himself, then, ignoring interruptions, he gave the coup de grâce in his soft Welsh voice¶ as he made the case for Chamberlain to resign:

I was not here when the Right Honorable Gentleman made the observation, but he definitely appealed on a question which is a great national, Imperial and world issue. He said, “I have got my friends.” It is not a question of who are the Prime Minister’s friends. It is a far bigger issue. The Prime Minister must remember that he has met this formidable foe of ours in peace and in war. He has always been worsted. He is not in a position to appeal on the ground of friendship. He has appealed for sacrifice. The nation is prepared for every sacrifice so long as it has leadership, so long as the Government show clearly what they are aiming at and so long as the nation is confident that those who are leading it are doing their best. I say solemnly that the Prime Minister should give an example of sacrifice, because there is nothing which can contribute more to victory in this war than that he should sacrifice the seals of office.

Churchill concluded the debate, after attacks on Chamberlain from both sides of the House, with a long and ferocious defense of Chamberlain. Churchill was honor bound as a member of the government to do so, but his mastery of the House, despite constant catcalls and interruptions, made it clear how much better he was suited to the prime ministership than was Chamberlain. After a tense and angry division—Spears remembers the expression of “implacable resentment” on the face of Government Chief Whip David Margesson as he noted which Conservative members were voting against the government or abstaining—the government won by eighty-one votes, to shouts of “Resign! Resign!” and “Go! Go!”

To win by only eighty-one votes with a majority of over two hundred was tantamount to defeat—certainly it was a stinging indictment of the government’s conduct of the war. Chips Channon, a faithful supporter of the prime minister, caught sight of Mrs. Chamberlain in the speaker’s gallery: “She was in black—black hat—black coat—black gloves—with only a bunch of violets in her coat. She looked infinitely sad as she peered down into the arena where the lions were out for her husband’s blood.” Spears noted Chamberlain’s expression as he rose to his feet, of “cold aloofness, even disdain.” Chamberlain “turned, picking his way over the protruding feet of his colleagues, as he always had to do from the Treasury Box to the Speaker’s Chair, but before he got there, whilst still in view of the House, he seemed to grow even slighter than usual, and his erect figure bent. He walked out of the House and through the lobby with heavy feet, a truly sad and pathetic figure . . . solitary, following in the wake of all his dead hopes and fruitless efforts.” There were no crowds to cheer him now. As Chips Channon wrote, he was now “only a solitary little man who had done his best for England.”

Gracie Fields’s famous 1932 music hall song “He’s Dead But He Won’t Lie Down” best describes Chamberlain’s position on the night of May 8. “Solitary” he might be, but he still cherished hope, however faint, that he could form a “national” government, that is, a coalition of the major parties. To the extent that he did, such hope evaporated almost completely the next day. Brendan Bracken, Churchill’s ubiquitous political “fixer,” had already sounded out Attlee about whether Labour would serve in a government led by Chamberlain, and came away with the impression that Labour would not, but might agree to serve in a coalition government led by Lord Halifax or, with rather less enthusiasm, by Churchill.

Within the Conservative Party sentiment for Halifax as Chamberlain’s replacement was growing. Halifax was trusted, reliable, respected, and respectable, a friend of the king and queen,# both of whom hoped that he would replace Chamberlain if a change proved to be necessary. Indeed the royal couple liked Halifax so much that they had given him his own key to the Buckingham Palace gardens, so he could walk through them on his way to the Foreign Office every morning. Churchill was, as the saying goes, “damaged goods”—the queen had not yet forgiven him for his noisy support in favor of the marriage of King Edward VIII and Mrs. Simpson, when Churchill had let his heart, his sympathy for the king, and his instinctive royalism overcome his caution. Churchill, whose greatest fault was a blindness to other people’s feelings—he always assumed he had won over anybody he talked to—was happily unaware of any lingering hostility toward him on the part of the king and queen. He failed to gauge the king’s “natural shyness” and the extent to which, as Channon noted, “an inferiority complex towards his eldest brother made him on the defensive,” or the degree to which he “was almost entirely dependent on the Queen whom he worshipped.” It would take Churchill some time to win over the royal couple, not to mention his own party. Many in the Conservative Party still decried him as “a half-breed American,” “a wild man” who loved war for its own sake and who was responsible for a whole roster of things that ordinary Conservatives disliked, from Mrs. Simpson to Gallipoli.

Small groups of those anti-appeasers who supported Churchill huddled together on the morning of May 9. Duff Cooper, Leo Amery, Edward Spears, and Harold Nicolson all attest to an intense “huggermugger” intended to persuade Chamberlain that he must resign and name Churchill as his successor, while in 10 Downing Street the prime minister, with the help of David Margesson, who was the most accurate gauge of the state of mind of the Conservative Party, saw a stream of backbenchers and tested out the possibility that throwing Simon and Hoare overboard might be enough to satisfy the less extreme malcontents. In The Holy Fox, his masterly biography of Lord Halifax, Andrew Roberts suggests that Chamberlain even went so far as to offer Leo Amery a choice of “either the Chancellorship of the Exchequer or the Foreign Office,” although the latter would have meant sacrificing Halifax. Chamberlain remained a shrewd and ruthless politician and might have thought it worthwhile to divide his opponents within the party by enlisting one of his most outspoken critics in an office so high that he could not reject it. Since the source for this is Labour MP Hugh Dalton, who would only have heard it secondhand, it may not be true, but if the offer was actually made, or even suggested, it indicates that Chamberlain was determined not to go down without a fight on the morning of May 9, and still felt he had a few good cards left in his hand. Perhaps like any professional politician he was just trying to keep his options open.

Duff Cooper.

In any event, by midday Margesson’s soundings among the party had made it clear to him that Chamberlain must go. Margesson was the ruthless party disciplinarian, the dispenser of patronage, the Tory Party’s equivalent of Ko-Ko the Lord High Executioner in The Mikado.** He had been a devoted and fierce supporter of Chamberlain, feared and loathed by the appeasers, but his primary loyalty was to the party, not to the prime minister, and once it was evident to him that the party was too badly shaken by the two days of debate about Norway to rally behind Chamberlain, Margesson firmly and frankly gave him the bad news.

Chamberlain understood at once—if the chief whip reported that the party and the mood in the constituencies was disturbed by the controversy, then it was time to resign and secure the prime ministership for Halifax before it was too late. Halifax remained the undisputed choice of the party, of the royal family, and of Chamberlain himself.

Early in the afternoon Chamberlain, Churchill, Halifax, and Margesson met with the two most prominent Labour leaders, Clement Attlee and Arthur Greenwood, in the Cabinet Room at 10 Downing Street, the four Conservatives on one side of the big table, the two Labourites facing them. There was no drama, and no rhetoric, it was all very polite and English, but Attlee and Greenwood made it clear that they did not believe Labour would agree to join a national government under Chamberlain, although the final decision would have to be made at the Labour Party’s annual conference at the seaside resort of Bournemouth. They did not express a preference for Churchill or Halifax—that too would have to be discussed in Bournemouth, which was about to take place. They left quietly, and there was a moment of silence as the four Conservatives contemplated what now seemed like an inevitable decision.

There was no animosity between Churchill and Halifax—after the departure of the two Labour leaders they left the prime minister for a time and quietly shared a pot of tea in the garden of 10 Downing Street in the “bright, sunny afternoon,” which, if it is true, must be one of the few times that Churchill ever accepted a cup of tea as a refreshment instead of a weak whiskey soda.

At some point in the afternoon—accounts differ about the time—they gathered again in the Cabinet Room, Chamberlain, Halifax, Churchill, and Margesson, and Chamberlain asked whom he should appoint as his successor. Churchill’s friends Bracken and Beaverbrook had foreseen this moment, and urged him to remain silent—no easy task for a man who was by nature a great talker, argumentative, emotional, and impulsive. Churchill’s own account of the critical moment is dramatic, but not entirely accurate, since he gets the date wrong and omits the presence of Margesson, who was a key player. Chamberlain made it clear that he preferred Halifax as his successor, and Halifax did not apparently think it necessary to mention his hope that the war could still be brought to an end by careful diplomacy—the ultimate triumph of appeasement.

At the same time, Halifax appears to have had doubts that he was the right man, or perhaps more important that he could control and influence Churchill from the House of Lords as “his number two.” As Andrew Roberts puts it, Halifax might be “in a more powerful position behind the throne than sitting on it.” Certainly Halifax thought it was his duty to restrain and advise Churchill, though he did not say so at the time. Instead, he once again brought up, after a long silence, his doubt that he could lead the country effectively from the House of Lords.

This was not, in fact, as difficult a problem as Churchill makes it out to be. Given the national crisis, a way could have been found to seat Halifax in the House of Commons. The king would later—too late by a day, as it happened—suggest that Halifax’s peerage could have been placed “in abeyance” for the duration of the war. However, Halifax’s doubt that he could be an effective leader if he wasn’t “in charge of the war” or able to lead in the House hung in the air for what seemed to Churchill “a very long pause,” one that seemed to him to go on longer “than the two minutes [of silence] which one observes in the commemorations of Armistice Day,” during which Churchill got up and stared out the window, his broad back turned to the other three men.

Silence, as Bracken and Beaverbrook had advised, was his best answer. It validated the doubts Halifax had expressed about becoming prime minister himself, and confirmed Churchill’s belief that in the circumstances he was the right man—the only man—for the job. This has been interpreted as a moment of self-sacrifice and “self-abnegation” on the part of Halifax, and so it may have been: after all, he was an ambitious man, a former viceroy of India, and in no doubt that he could do the job, indeed he may even have wanted it—but at the critical moment he did not, or perhaps would not, say so. Possibly it was out of pride, or a lifelong unwillingness to admit to his own ambition. In Halifax’s life, honors had presented themselves to him, and would continue to do so, without his ever appearing to seek them out—the viceroyalty, the Garter, the chancellorship of Oxford University—though in his quiet way he was more Machiavellian in pursuit of what he wanted than he seemed to be. He may indeed even have supposed that Churchill would fail and that he would be the one who would pick up the pieces and bring an end to the war. In any case, Halifax did not speak out, and Churchill took his silence for consent. As he put it, he decided that “the duty would fall upon me—had in fact fallen upon me.”

In the face of a bolder and stronger personality, Halifax and Chamberlain had given way, and Margesson, always the supreme political realist, decided to switch sides, confident that he could persuade the Conservative members of the House to accept Churchill, with whatever doubts and reservations they might have, instead of the man they wanted. After all, if Margesson, the man in charge of party discipline, could change sides, who were they to disagree?

Churchill broke the silence by saying that he would have “no communication with either of the Opposition parties [Labour and the much smaller Liberal Party] until [he] had the King’s commission to form a Government,” having in effect, like Napoleon at his coronation, placed the crown on his own head.†† He went back to the Admiralty and let events take their course, or so he says—it seems more likely that he spent the night communicating to his friends and supporters. Certainly, he dined that night with Anthony Eden, whom he told that Chamberlain “would advise King to send for him” the next day, and to whom he offered the post of Secretary of State for War. Eden described Churchill as “quiet and calm.” Churchill spoke by telephone to his son, Randolph, and told him, “I think I shall be Prime Minister tomorrow.”

At five in the morning of May 10 the news came that Germany had attacked Holland, Belgium, and France, the long-awaited attack on the west. Luxembourg too had been invaded—the first sign, had anyone been aware of the danger and looking in that direction, of Manstein’s plan to send the panzer divisions through the Ardennes toward Sedan, instead of through Belgium toward the Somme River. Churchill was woken in his apartment at the Admiralty and convened the other two service ministers, the secretary of state for war and the secretary of state for air, to meet with him at once. As a sign of things to come, he ate a hearty breakfast as the bad news poured in. “We had had little or no sleep, and the news could not have been worse,” Sir Samuel Hoare wrote later. “Yet there he was, smoking his large cigar and eating fried eggs and bacon, as if he had just returned from an early morning ride.”

Reports came in of heavy bombings of cities in Holland and the dropping of German parachute troops, then a novelty, in both Holland and Belgium; more important were accounts that the British and French armies had begun their advance into Belgium—Gamelin’s famous Plan D was taking place as intended. The French were so overwhelmed by the news of the German attack that they at last agreed to let Churchill’s scheme for mining the Rhine proceed.

In 10 Downing Street the news brought about an unwelcome change of heart in Neville Chamberlain, who now thought it was his duty to remain prime minister until “the French battle” was finished. Sir Kingsley Wood, hitherto a faithful supporter, talked Chamberlain out of this calamitous illusion by ten in the morning.

Throughout the day in matters great and small one can sense, in every account, the presence of Winston Churchill taking over the reins of government, although he was not yet prime minister. He brought his scientific adviser Frederick Lindemann, the Prof, with him to an early-morning War Cabinet to demonstrate a new homing (or proximity) fuse for antiaircraft shells, provoking General Ironside to ask, “Do you think this is the time for showing off toys?” He suggested that the Foreign Office offer sanctuary in Britain to the eighty-one-year-old Kaiser Wilhelm II, who had been living in exile in Holland since 1918.‡‡ He asked the War Cabinet to send Admiral of the Fleet Sir Roger Keyes to Brussels “to offer his counsel and support to the King of the Belgians, with whom he was on terms of close personal friendship,” thus establishing what we would now call a separate “back channel” to the Belgian king. He ordered the Royal Navy to remove the Dutch gold reserves before they fell into German hands. Before the day was out the Dutch ministers, “haggard and worn,” had flown to London to say that the Germans had attacked them without any warning or pretext, that cities had been bombed and large numbers of civilians killed, and that Holland had already opened the dikes to flood large stretches of land and slow down the German advance.

By the late afternoon the word that Churchill was to become the prime minister had begun to spread, though not yet to the newspapers. John Colville, the handsome and engaging young assistant private secretary to the prime minister, and therefore “in the know,” noted in his diary the reaction of most Conservatives to the news:

At about 4:45 Attlee rang up to say that they would agree to join a Government provided Neville Chamberlain was not PM. . . . Provided the PM and Halifax remain in the War Cabinet there will at least be some restraint on our new War Lord. He may, of course, be the man of drive and energy the country believes him to be . . . but it is a terrible risk, it involves the danger of rash and spectacular exploits. . . . Nothing can stop him having his way—because of his powers of blackmail—unless the King makes full use of his prerogative and sends for another man; unfortunately there is only one other, the unpersuadable Halifax. Everybody here is in despair at the prospect.

To be fair, Colville would soon change his mind, and become devoted to Churchill, but on May 10 his was the prevailing opinion. Mrs. Churchill was out of London attending her brother-in-law’s funeral, but Churchill called her and asked her to return as soon as possible. Chamberlain finally sought an audience with the king, who saw him “after tea.” Chamberlain told him that he wished to resign, and the king, deeply perturbed, told him “how grossly unfairly” he thought Chamberlain had been treated and added that he “was terribly sorry all this controversy had happened.” The king reluctantly accepted Chamberlain’s resignation, suggested that Halifax was “the obvious man” to replace him, and was taken aback to learn that Halifax had ruled himself out. “Then I knew,” the king wrote, “that there was only one person whom I could send for to form a Government who had the confidence of the country, & that was Winston.”

Churchill with his bodyguard, Inspector W. H. Thompson of Scotland Yard.

A messenger summoned Churchill to Buckingham Palace at six o’clock. Mrs. Churchill had arrived back by then and accompanied her husband to the palace, where Churchill was taken directly to see the king. The king asked him to sit, and said, “I suppose you don’t know why I have sent for you?” Churchill replied with a wry grin, “Sir, I simply could not imagine why,” and the king promptly asked him to form a government. Churchill said he would do so, then drove back to the Admiralty.

It was only a two-minute drive from the palace to the Admiralty, and when Churchill got out of his car he turned to his bodyguard, Inspector W. H. Thompson,§§ and said, “You know why I have been to Buckingham Palace, Thompson?” Thompson said he did and congratulated him on his “enormous task.” Churchill paused, then said, “God alone knows how great it is. All I hope is that it is not too late. I am very much afraid it is. We can only do our best.”

“Tears came into his eyes,” Thompson related. “As he turned away he muttered something to himself. Then he set his jaw, and with a look of determination, mastering all emotion, he began to climb the stairs.”

_________________________

* To put this in perspective, President Roosevelt was only fifty-eight in 1940, Hitler fifty-one.

† Major-General Sir Edward Spears relates that in society those who did not like Mme de Crussole described her as “la sardine qui s’est crue sole” (the sardine who thinks she’s a sole), but the translation of course misses the pun on her name.

‡ Sir Horace Wilson was the head of the Home Civil Service, normally an important but innocuous bureaucratic post, which did not involve giving advice on foreign policy or military affairs.

§ The others were Winston Churchill, Harold Nicolson, and Anthony Eden.

¶ Lloyd George was the first and last British prime minister for whom English was not his or her first language.

# Future beloved “Queen Mum,” mother of Queen Elizabeth II.

** Following this analogy, it would be amusing—and perhaps instructive—to think of Lord Halifax as the Tory Party’s equivalent of Pooh-Bah the Lord High Everything Else.

†† Although Napoleon brought the pope to Paris in 1804 to crown him emperor of the French in Notre Dame Cathedral, he took the crown from the pope and crowned himself in a dramatic gesture at the last moment, an act of supreme power that was lost on no one.

‡‡ This was done, but after two days in which to think it over, the Kaiser politely declined the offer and remained in Holland, provided with an honor guard of German troops until his death in June 1941.

§§ Thompson had been Churchill’s bodyguard since 1921, when he was assigned by Scotland Yard because of threats to Churchill’s life from the IRA.