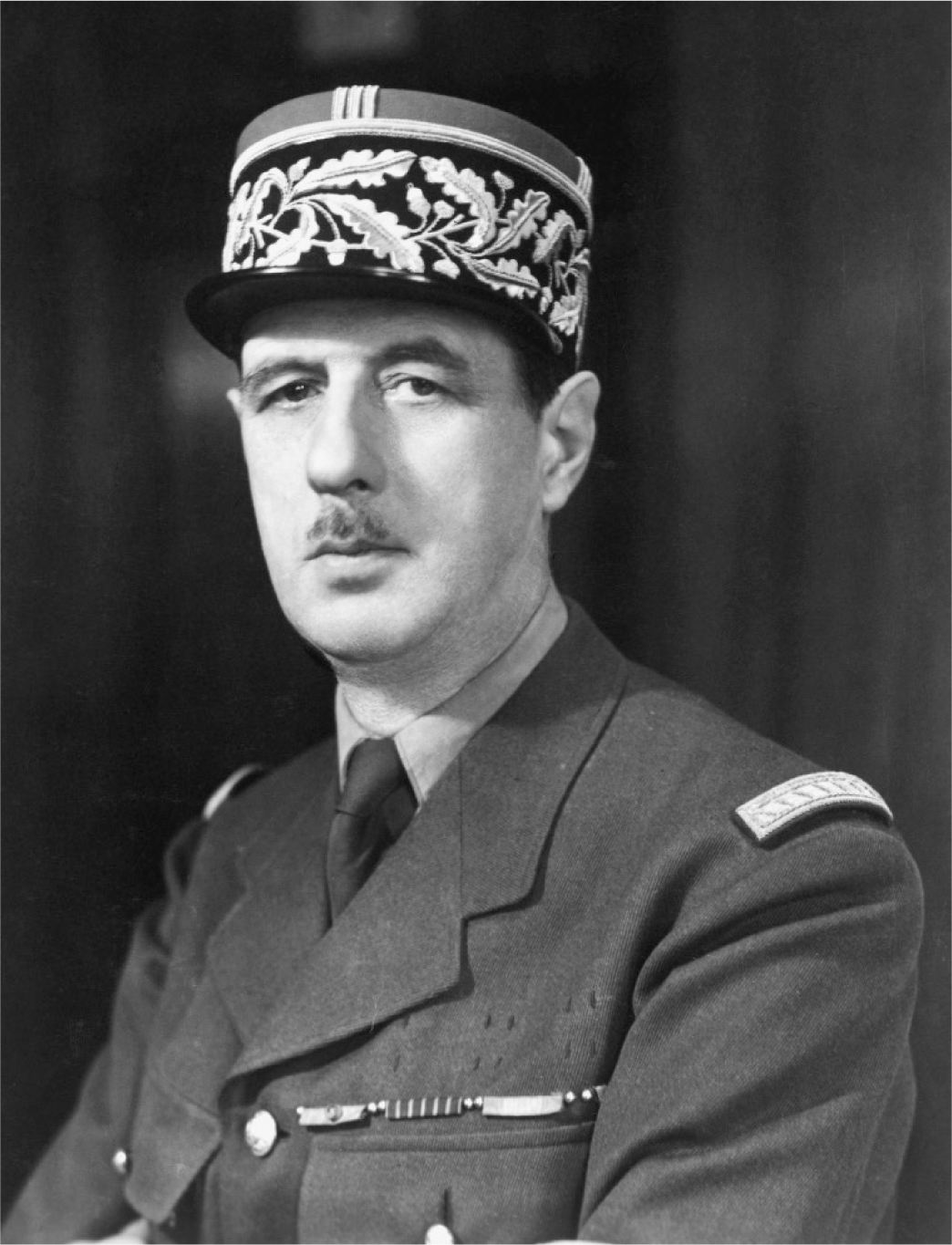

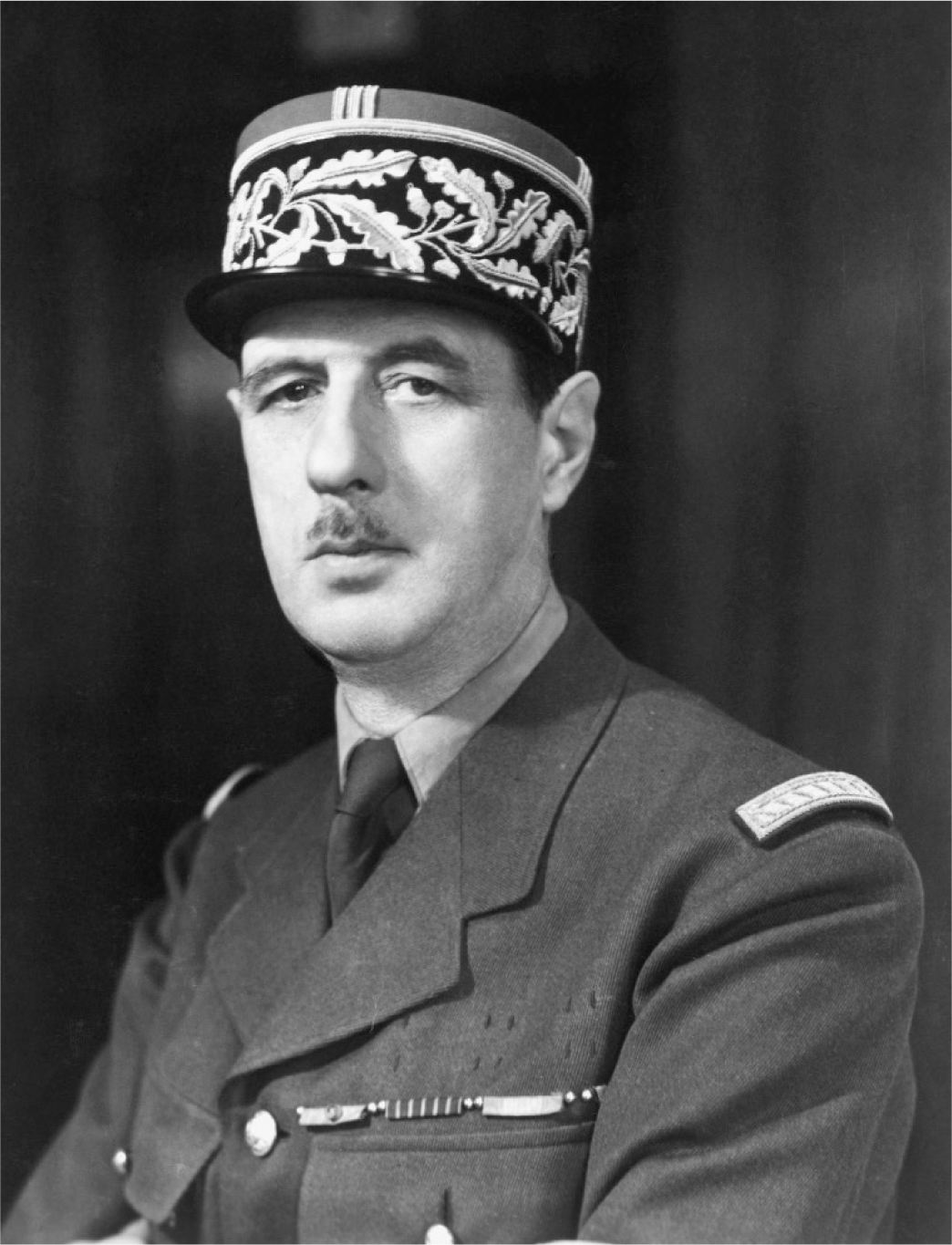

General de Gaulle.

General de Gaulle.

“THE WHOLE ART of war consists in getting at what lies on the other side of the hill.” The Duke of Wellington’s famous remark held as true in May 1940 as it had before Waterloo. Merely because the French were in a state of panic at the speed and impact of the German advance did not necessarily signify that the German Army and its Führer were happy and confident. On the Allied side, Winston Churchill still remained mistakenly convinced that the German panzer divisions would eventually run out of fuel or enthusiasm, and that the mass of the infantry divisions was a long way behind them, and exhausted, offering a ripe target for a vigorous counterattack.

This opinion was shared “on the other side of the hill” by the more cautious, and for the most part more senior, German generals, as well as intermittently by Hitler himself. Like a gambler whose first bets at the table have been successful, he was torn between caution and going for broke. In September 1939, when he had staked everything on his intuition that Chamberlain would not declare war over Poland, Hitler told Göring that he had decided to play “va banque” (a French phrase used in playing baccarat, which passed into German as the equivalent of “going for broke”), to which Göring replied, “But have we not always played va banque, mein Führer?”

This was true enough, Hitler’s nerve had never failed him in the past, but it is important to bear in mind that he, like the rest of the world, still had an exaggerated respect for the French Army, and for France’s position as a world power. Isolating and defeating the BEF, which was a tenth the size of the French Army, did not seem to him as important as defeating France and securing Germany’s revenge for the humiliating surrender of November 11, 1918. Still influenced by Ribbentrop’s conviction that once “the right people” came to power in London the British would see reason and agree to German peace terms, the fate of the BEF did not loom large in his mind the way it did for the British—or for some of his own generals.

As early as May 12 and 13 the rapid breakthrough of Guderian’s panzer divisions was already beginning to cause concern higher up the German chain of command. General Ewald von Kleist, commander of Panzergruppe von Kleist and Guderian’s immediate superior, attempted to rein Guderian in, both in expectation of a French counterattack from the reserves behind the Maginot Line—the Germans estimated that “thirty to forty divisions” were available there for this purpose—and in order to give the infantry time to catch up with the tanks. Unfortunately for the Allies, no such idea crossed General Weygand’s mind. Guderian argued that Kleist was “giving away the German victory to the French,” strong words even for him. Their disagreement became so heated that Guderian threatened to resign if he was not allowed to continue, then made its way all the way up to Colonel General von Rundstedt, commander of Army Group B, and from there to the OKH, the Army High Command, and to Hitler himself.

Eventually Guderian managed to regain control of his fiery temper, and a face-saving compromise was reached—he was allowed to push forward “a reconnaissance in force” toward the west, which quickly gathered strength and speed just as he had intended, only under another name. However, twenty-four hours had been wasted, and as Napoleon pointed out, “Space we can recover, but time never.”

Fierce fighting throughout the breakthrough area on May 14 and 15, combined with reports of heavy German casualties and lack of food, water, ammunition, and fuel, made the problem reappear almost at once. On the night of May 15–16 OKH, apparently suffering from cold feet again, ordered Kleist to “suspend all westward movements,” igniting another furious outburst from Guderian, who sensed that his advance was “rapidly developing into a pursuit” and that it was by now too late for the French to bring up fresh divisions for a major counterattack in force. This time Kleist backed his willful subordinate, and on May 16 the panzer columns were freed to “advance westwards unimpeded.”

By now the German tank crews were no longer bothering to take prisoners. They passed long columns of retreating French infantry on the road and simply disarmed them, sometimes ordering them to pile their weapons by the side of the road, then running over them with a tank to destroy them. There was no time to round up prisoners of war, or for the niceties of accepting their surrender; Guderian’s goal was to reach the Channel as quickly as possible before the French or OKH had a chance to stop him.

Although Rommel’s division was not part of Panzergruppe von Kleist—he was advancing ahead of Guderian’s panzer divisions, on their right flank, as if it were a race to the sea—like Guderian, Rommel dealt with orders to halt or slow down by simply ignoring them, plunging forward in a plume of dust along roads packed with refugees and French military personnel fleeing toward the west, and benefiting from breakdowns in radio communication to keep his tanks going at all costs. When enemy tanks appeared he put them out of action without stopping and moved on, and wherever he found the way forward blocked by French military vehicles intermingled with the cars, trucks, and carts and horses of refugees, he simply took to the fields with his tanks and bypassed them. His account of one incident during May 17 gives a picture of what all the panzer divisions were experiencing as General Corap’s army collapsed.

Hundreds upon hundreds of French troops, with their officers, surrendered at our arrival. At some points they had to be fetched out of vehicles driving along beside us.

Particularly irate over this sudden disturbance was a French lieutenant-colonel whom we overtook with his car jammed in the press of vehicles. I asked him for his rank and appointment. His eyes glowed hate and impotent fury and he gave the impression of being a thoroughly fanatical type. There being every likelihood, with so much traffic on the road, that our column would get split up from time to time, I decided on second thoughts to take him along with us. He was already fifty yards away to the east when he was fetched back to Colonel Rothenburg, who signed to him to get in his tank. But he curtly refused to come with us, so, after summoning him three times to get in, there was nothing for it but to shoot him.

This is a description of the horrors of war worthy of Hemingway (or perhaps Goya) in its matter-of-fact portrayal of a small incident with its brutal surprise ending,* typical of so many others as the German panzer divisions passed through towns and villages on their way to the Channel. It was not for lack of brave officers and soldiers that the French Army was collapsing; it was more because of fatal strategic misjudgment, paralysis of will, helpless pessimism, and political intrigue at the top, combined with certain areas in which the French armed forces were poorly equipped for a modern war, especially an inadequate and obsolete air force.

Over the years French investment in aircraft had been spread over too many different (and inferior) types, without a strong direction or strategy for their use—even a last-minute splurge on buying modern aircraft from the United States could not provide France with a first-rate air force. As for tanks, the French had more of them than the Germans and their newer types were heavier, better armored, and better armed, but they suffered from weak tracks, awkward refueling in the field, and lack of a well-organized system of radio communications. They had been designed in fact, like almost everything else in the French armed forces, for supporting the infantry, not for traveling long distances—the French, after all, had never intended to attack anybody. From the building of the Maginot Line to the formation of the air force, the dominating philosophy of French defense policy was to avoid a war, not to fight one. When that cautious policy failed, it could not be replaced overnight by a sudden return to Foch’s attack à l’outrance of 1914—furious bayonet charges would not stop tanks or dive-bombers.

The truth is that neither on the left nor on the right over the last twenty years had there ever been a desire to wage war—indeed on the extreme right there were those who admired Hitler and the “new” Germany, on the extreme left those who still could not believe that the Soviet Union would behave with the same callous selfishness as any other great power and support Nazi Germany. Nobody in France needed to be reminded that last time it had required France, Britain, Italy, Russia, and the United States to defeat Germany—and even then by only the narrowest of margins. Hardly anybody believed that France could win a war against Germany with Britain as its only ally, while Russia and the United States remained neutral and Italy threatened to join Germany.

Commitment to the defensive inevitably sapped France of its will, and ultimately its potential to attack, like a boxer who stands in the middle of the ring and allows his opponent to hit him without striking back. During the first week of the German attack, in the words of then Colonel Charles de Gaulle, “Our fate was sealed. Down the fatal slope to which a fatal error had long committed us, the Army, the state, France were now spinning at a giddy speed.”

By a supreme irony, de Gaulle was called upon, now that it was too late, to take command of a last-minute attempt to slow down the rush of the German armored divisions. Immensely tall, austere, but with a scalding, sardonic sense of humor that does not translate easily into English, a devout Catholic in an army in which clericalism was controversial, at once an aloof intellectual and a fierce warrior, de Gaulle had fought heroically in the First World War—he was seriously wounded, gassed, and taken prisoner during the Battle of Verdun, that epic ten-month conflict in which the Germans attempted “to bleed the French army to death,” but which ended in a stalemate that cost over 750,000† casualties to both sides—perhaps the bloodiest battle in history. An aide and protégé of Marshal Pétain, the victor of Verdun, de Gaulle’s belief that mechanized warfare would transform the battlefield, boldly outlined in a book that was greeted with skepticism and outright ridicule in France, had slowed his promotion, and rendered him anathema to many of his own chiefs. De Gaulle had prophesied that relatively small numbers of fast-moving tanks would pierce even the best-planned and strongest of defensive lines (“the fixed and continuous front,” as de Gaulle described it with contempt) and swiftly paralyze an army by disrupting its lines of communication, thus dismissing at one stroke both French strategy and the Maginot Line. Guderian proved the validity of de Gaulle’s thesis in less than a week.

De Gaulle’s admiration for his former grand chef Marshal Pétain was also ironical, and curiously self-revealing. He recognized the older man’s contempt for people of less intelligence and courage than himself, his colossal vanity that could never be satisfied by “the bitter caresses” of mere military glory, his tendency to identify himself with France as if they were one and the same. De Gaulle’s description of Pétain’s character is a perceptive, and perhaps also an unconscious, self-portrait: “Too proud for intrigue, too forceful for mediocrity, too ambitious to be a mere time-server, he nourished in his solitude a passion for domination. . . .”

The day after the German attack on the west on May 10 de Gaulle was ordered to take command of the 4th Armored Division, which did not yet exist, but was being cobbled together out of bits and pieces of other units, and to assemble it as rapidly as possible at Laon. Treated with a certain, but predictable, coldness at the GQG in Vincennes, he was greeted with slightly greater, if patronizing, warmth by General Georges at his headquarters on May 15. “There, de Gaulle! For you, who have so long held the ideas which the enemy is putting into practice, here is the chance to act.”

De Gaulle set up his headquarters at Bruyère, south of Laon, and perceived at once that the enemy was moving directly west, with his flank on the Serre River. His reconnaissance was slowed by “miserable processions of refugees” and by soldiers who had been told to surrender their weapon and “make off to the south so as not to clutter up the roads.” The spectacle moved de Gaulle powerfully: “At the sight of those bewildered people and of those soldiers in rout, at the tale, too, of that contemptuous piece of insolence of the enemy’s, I felt myself bourne up by a limitless fury. Ah! It’s too stupid! The war is beginning as badly as it could. Therefore it must go on. For that the world is wide. If I live, I will fight, wherever I must, as long as I must, until the enemy is defeated and the national stain washed clean. All I have managed to do since was resolved upon that day.”

De Gaulle was a natural leader of men. Not only did he tower over them in height; he dominated them by his cold courage, his forceful mind, and his contempt for those who did not live up to his standards—or to the country’s, for de Gaulle believed, and would always believe, that “France cannot be France without greatness.”

He put his ramshackle, improvised, and untrained armored division into action by dawn on May 17, sweeping twelve miles forward toward Montcornet, on the Serre River, under constant attack from German dive-bombers. By nightfall he had taken 130 German prisoners, and given a rude shock to German troops of the 1st Panzer Division who had crossed the Serre.

On the nineteenth he regrouped and attacked again, this time to the north of Laon, but without air support and woefully short of infantry he was unable to cross the Serre, and was ordered by General Georges to break off the attack. De Gaulle has been criticized by even so eminent, fair-minded, and Francophile a military historian as Sir Alistair Horne for transforming this comparatively small and ineffective engagement into an element of his own myth, but while there is some truth to that (it did not slow down Guderian, who did not even bother to report the incident to Kleist), for de Gaulle it had a whole other significance. In the vast military chaos that stretched from the Maginot Line to the English Channel, he had attacked, inflicted casualties, taken prisoners, his men had fought aggressively and well, he was not wrong to believe that if four or five similar French armored divisions had been available to attack the left wing of the German panzer thrust, history might have been dramatically altered. He could not help “imagining what the mechanized army of which [he] had so long dreamed could have done,” and he was right. But it did not exist.

* * *

De Gaulle would repeat his feat at Abbeville, moving his division one hundred fifty-five miles west in five days, itself no mean accomplishment, to form part of a last-ditch Anglo-French attack intended to cut off and destroy the German bridgehead over the Somme. This too failed, with heavy losses on both sides, but the three-day battle would reverberate up the German chain of command with serious consequences, and would give de Gaulle a reputation that would bring him to the French cabinet as undersecretary of state for national defense, and, at last, to the rank of brigadier general, which he would hold for life—even as president of the Fifth Republic he would almost always be referred to by everyone as “General de Gaulle,” or as “le général,” as if no other identification was necessary.

_________________________

* Perhaps even more surprising is a German officer describing a French one as “fanatical.” Fanaticism is possibly in the eye of the beholder, rather than a national or ethnic characteristic.

† Some estimates put the number of casualties at Verdun closer to a million. The remains of bodies are still being dug up today, with no end in sight.