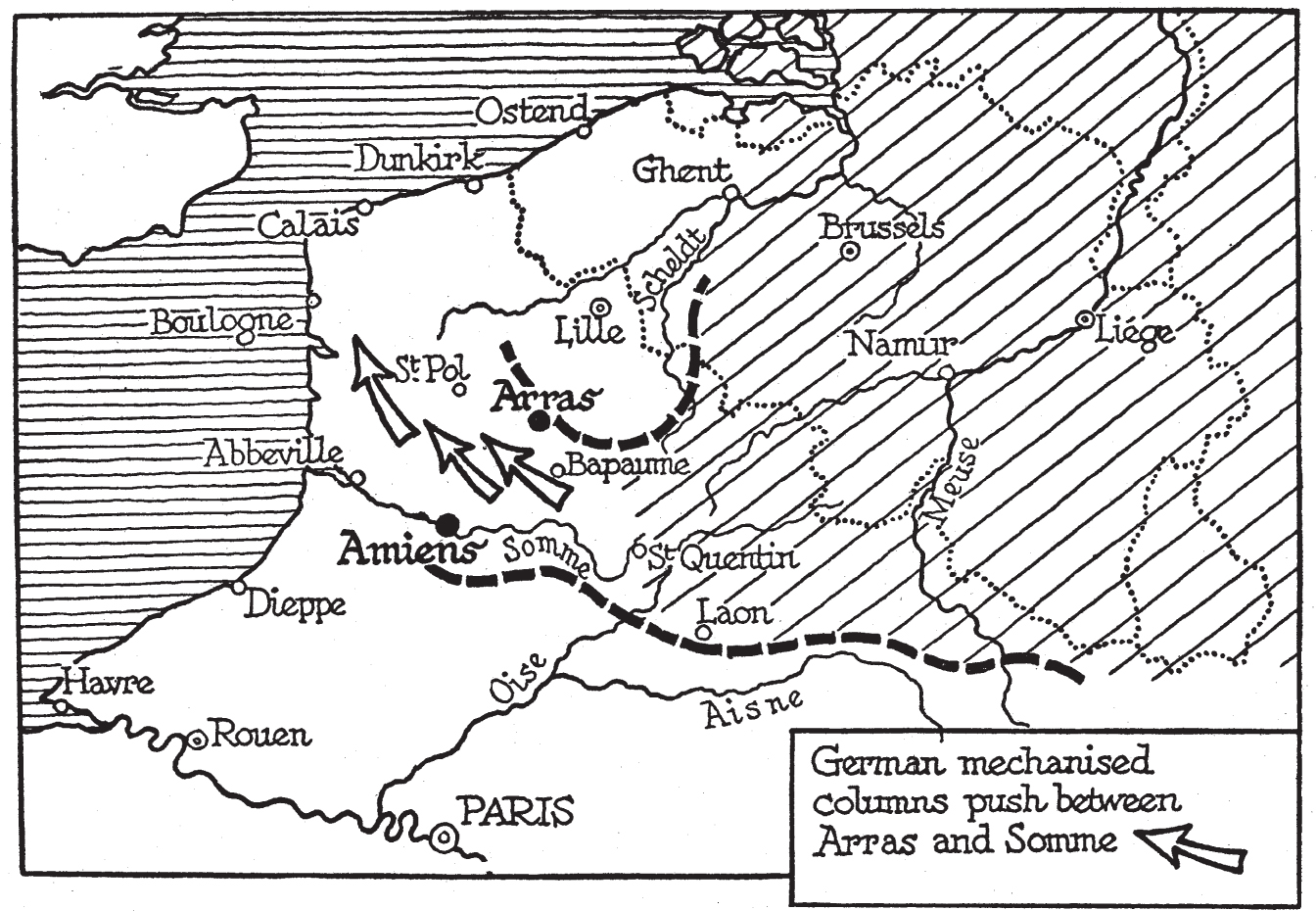

UNFORTUNATELY DE GAULLE’S attack passed almost unnoticed in Britain. The Times reported that the BEF had been withdrawn from Brussels (bad news for Belgium, but not seen as so serious from London) and that a “readjustment of the front” was taking place, a masterly phrase—one senses Brendan Bracken’s hand at work here—to cover a widespread retreat. The Air Ministry, never at a loss for producing good news from disaster, boasted shooting down over 1,000 German aircraft in a week—in fact the Luftwaffe lost only 1,266 aircraft during the entire campaign, nearly 300 of them as a result of accidents. The more popular papers reported that German attacks were being “repulsed,” although even the tabloid papers had at last woken up to the fact that the French and British armies had effectively broken off any attempt to hold a line in Belgium, and that the main thrust of the German Army was no longer there, but across the Meuse and directly toward the English Channel. It did not require any great degree of strategic knowledge to look at the maps on the front page of the newspapers and see that once the Germans reached the sea the BEF, at least one French army, and the entire Belgian Army would be cut off from the bulk of the French Army and effectively surrounded, with their backs to the sea.

My father, who was good at reading maps, glanced at the morning newspapers and silently shook his head in dismay, then went off to the studio to wrestle with the problems of producing The Thief of Baghdad, the sets for which now took up most of the soundstages at Denham, and to begin the rough sketches for the sets for That Hamilton Woman. That the film was to be about Admiral Nelson had not been explained to him—the script had not been completed and he had somehow been given to suppose it was to be about the Duke of Wellington and the Battle of Waterloo, and he had painted several views of an elaborate ballroom for the famous ball in Brussels that preceded the battle. When he showed them to my uncle Alex he shook his head in annoyance and said, “No, no, Vincikém,* it’s about the bloody admiral, not the bloody general—tear it all up and draw me a bedroom in a palace in Naples, for God’s sake!”

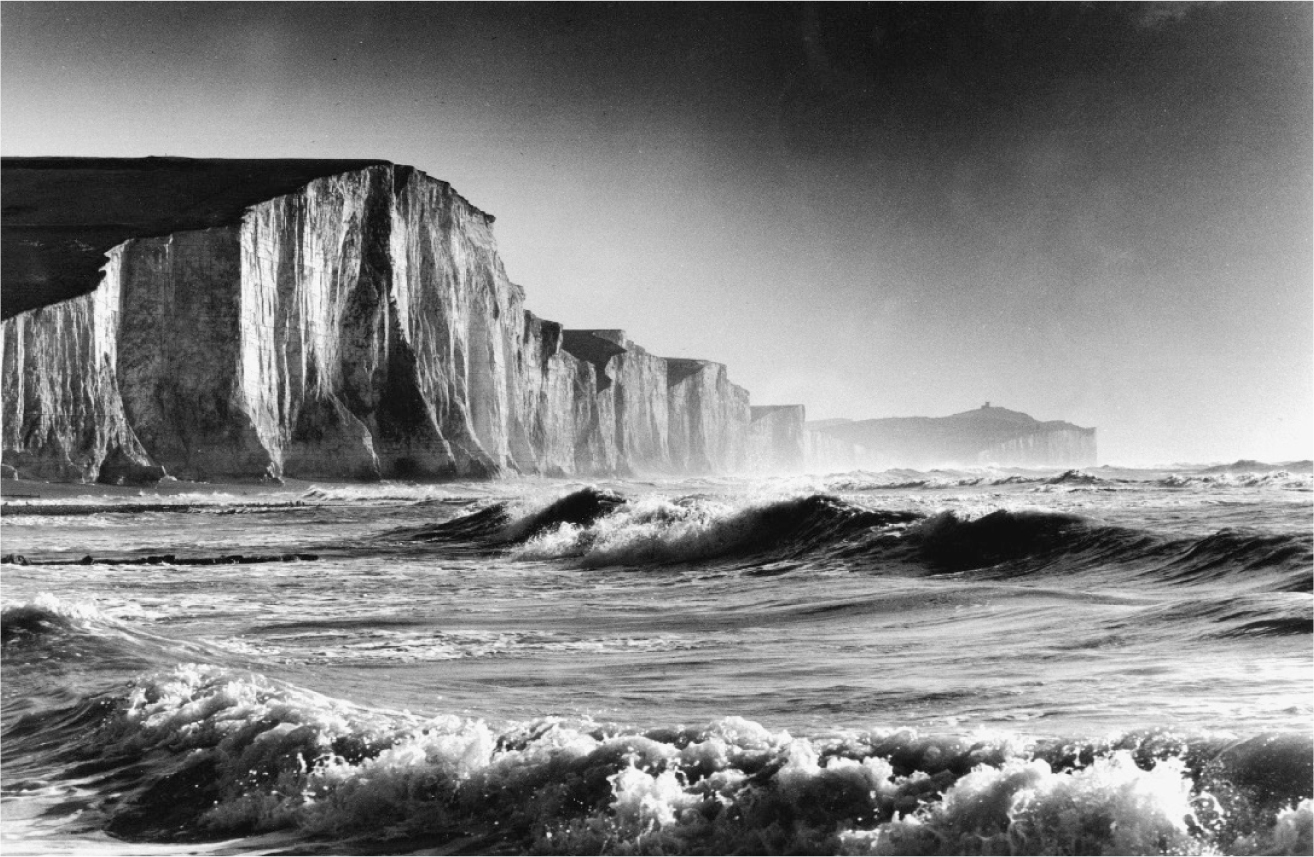

Vivien Leigh and Laurence Olivier in That Hamilton Woman.

As for my mother, she went off to work at the theater every night, apparently determined not to let the news diminish her normal high spirits, and by lucky chance I was so far spared the disruptions taking place on what was becoming referred to, no longer altogether facetiously, as “the home front.” Clare Boothe, yet another friend of my uncle Alex’s of course, noted that the government “continued to agitate (rather uselessly) for Londoners again to evacuate their children, who had been drifting back to London all winter and spring,” but in fact the pressures on families to evacuate their children were much more powerful than she supposed.

Operation Pied Piper, once it was set in motion, ground on remorselessly like any other civil service project—slum clearance, say, or tax collection. By keeping me moving between Hampstead, Denham, Yorkshire, and the Isle of Wight, my father had managed for the moment to outwit the authorities, who were busy moving millions of urban children to places where they were not wanted and had no desire to be. As Clare Boothe rightly predicted, the worse things got, the more people wanted to have their children with them, as opposed to being placed in the care of total strangers by the state.

The great events taking place in France did not prevent Churchill from keeping track of even the most minor matters of government, or even for thinking ahead to the future and imagining how to win the war. On the day of de Gaulle’s attack on Guderian’s flank—which would have given Churchill a good deal of pleasure had he known about it—his son, Randolph, on leave from his regiment, visited his father at Admiralty House, where he was still living owing to his reluctance to evict the Chamberlains from 10 Downing Street.

Randolph Churchill, Coco Chanel, and Winston Churchill at a boar hunt on the Duke of Westminster’s estate in France.

Randolph recalled the conversation.

I went up to my father’s bedroom. He was standing in front of his basin and was shaving with his old fashioned Valet razor. He had a tough beard, and as usual was hacking away.

WSC: “Sit down, dear boy, and read the papers while I finish shaving.” I did as told. After two or three minutes of hacking away, WSC half turned and said, “I think I see my way through.” He resumed his shaving. RSC was astounded, and said: “Do you mean we can avoid defeat?” (which seemed credible) “or beat the bastards” (which seemed incredible).

WSC flung his Valet razor in to the basin, swung around and said:—“Of course I mean we can beat them.”

RSC: “Well, I’m all for it, but I don’t see how you can do it.”

By this time WSC had dried and sponged his face and turning round to RSC, said with great intensity:—“I shall drag the United States in. . . .”

This was a farsighted and correct conclusion. Churchill could not have imagined that it would take nineteen more months before the United States entered the war, but he had seen clearly, from his very first letter to President Roosevelt, that it was his first duty to nourish the president’s sympathy for the Allied cause, and at the same time to use every means to persuade the American public that Britain would fight to the end, and that it was in America’s interest to support Britain—that its cause was worth supporting. He was particularly interested in the part that the British film industry could play to that end—in which my uncle Alex was already playing a leading role—Churchill was not too busy to read the early rough drafts of the script for That Hamilton Woman and add some patriotic flourishes of his own to it.

His task of convincing America that Britain would fight, and more important would win, was not made easier by the pessimism and isolationist views of the American ambassador to the Court of St. James, Joseph P. Kennedy. There was little or no trust or good feeling between the two men, and no more of Kennedy’s old privileged position, when for two years he had felt free to drop by 10 Downing Street for a cozy chat with Neville Chamberlain. It rankled Kennedy that he was obliged to pass on Churchill’s messages to the president, especially since Kennedy’s own messages to the president and his advice were often ignored, or replied to with the president’s trademark cheery blandness when Roosevelt disagreed with someone who thought himself close to him. When Kennedy wrote that he didn’t think Britain had “a Chinaman’s chance” of winning, the president simply ignored it. In his letters and his diary Kennedy constantly refers to Churchill’s drinking—Kennedy was himself a firm teetotaler although paradoxically the owner of a liquor company—and how “ill-conditioned” or “pasty” he looks, although those around Churchill all reflect the contrary, that he had never looked better or more energetic, as if crisis brought out the best in him, which was indeed the case. Like a nagging spinster aunt the ambassador never failed to remark on signs of Churchill’s drinking, noting, “There was a tray with plenty of liquor on it alongside him and he was drinking a Scotch highball, which I felt was indeed not the first one he had drunk that night,” or that there was a half-empty glass on his desk.

Ambassador Kennedy seems not to have been aware of the prime minister’s lifelong habit of sipping a weak Scotch and soda throughout the day, at moments when a lesser man might have asked for coffee or tea, but there was nobody else who failed to recognize that drunk or sober a new and stronger personality was in charge. Churchill cabled President Roosevelt (“We are determined to persevere to the very end whatever the result of the great battle raging in France may be. . . .”), he paused to read the transcript of a telephone call from General Swayne, head of the British Military Mission to French GQG, speaking for security in the guarded English of a doctor about the situation of the French Army (“Patient is rather lower and depressed. . . . The lower part of the wound continues to heal, but, as I expected, the upper part has started to suppurate again. . . .”); on being told by Mrs. Churchill that the preacher at St. Martin-in-the-Fields had given a defeatist sermon he recommended that the minister of information should have the offending clergyman “pilloried,” he urged that Lord Gort fight his way south toward Amiens to make contact with the French, and finally, after endless drafts prepared on a special noiseless typewriter with large type, he spoke to the British people for the first time on the BBC and told them, at last, the alarming truth, in the first of his great war speeches.

Ambassador Joseph P. Kennedy, with his sons Joseph Jr. and John (the future president).

A tremendous battle is raging in France and Flanders. The Germans, by a remarkable combination of air-bombing and heavily-armored tanks, have broken through the French defenses north of the Maginot Line and strong columns of their armored vehicles are ravaging the open country, which, for the first day or two, was without defenders. They have penetrated deeply and spread alarm and confusion in their track. Behind them there are now appearing Infantry in lorries and behind them again the large masses are moving forward. . . . Having received His Majesty’s commission I have formed an Administration of men and women of every Party, and of almost every point of view. We have differed and quarrelled in the past, but now one bond unites us all. To wage war until victory is won and never to surrender ourselves to servitude and shame whatever the cost and the agony may be. If this is one of the most awe-striking periods in the long history of France and Britain it is also beyond all doubt the most sublime. Side by side . . . the British and French peoples have advanced to rescue not Europe only but mankind from the foulest and most soul-destroying tyranny which has ever darkened and stained the pages of history. Behind them gather a group of shattered states and bludgeoned races, the Czechs, the Poles, the Norwegians, the Danes, the Dutch, the Belgians—upon all of whom the long night of barbarism will descend unbroken by even a star of hope, unless we conquer—as conquer we must—as conquer we shall.

I remember staying up to hear that speech, and being impressed by the profound seriousness with which it was given—and listened to by those around me. Even my father seemed moved, and Nanny Low cried openly. My mother may have been at the theater, I do not remember her being there at any rate. We sat in the dining room, my father beneath the De Chirico that he bought in Paris before the war (he had once shared a studio with De Chirico in Paris), the dog at his feet, an old glass jam jar filled with brandy beside him—he hated such fanciness as brandy snifters and balloon glasses, and preferred to use his folding pocketknife instead of a table knife. At that age I could have had no real understanding then of what was at stake, let alone that the speech was only aimed in part at British listeners. It was aimed, and shrewdly aimed, at President Roosevelt, a kind of grand, almost symphonic reply to the doubts of Ambassador Kennedy, and at those in the Conservative Party and in Britain who, like Kennedy, still preferred Neville Chamberlain, and dreamed of appeasement and a separate peace. If we were going to go down, we would go down fighting, Churchill told us, and the enemy was not just the Germans but “the foulest and most soul-destroying tyranny” in history, as good a description of Nazi Germany as can be found to this day.

Over the next few days the bland optimism of the newspaper headlines would change radically to a tone of gravity backed up by harsh truths, which were now out in the open. Things were bad. They were going to get worse, much worse, and the French Army—as well as our own BEF—was in retreat. Although Churchill lavished praise on France, there were, for those who listened carefully to the speech, a number of hints that the battle for France was being lost and that we might have to fight on alone, and also several carefully phrased appeals for help from the United States.

These were followed a day later by a darker (and franker) personal message to the president, reemphasizing that the present government would never surrender, but pointing out that if “members of the present Administration were finished and others came in to parley amid the ruins, you must not be blind to the fact that the sole remaining bargaining counter with Germany would be the Fleet, and if this country was left by the United States to its fate, no one would have the right to blame those then responsible if they made the best terms they could for the surviving inhabitants. . . .”

This was indeed a blunter message than what “A Former Naval Person” had so far been sending the president, and a tone that President Roosevelt was not used to hearing either, very close to a threat in fact, and a good indication that at some level of his mind Churchill was already aware that Lord Gort was probably not going to cut his way southward to Amiens to join with the French, and that in the prime minister’s own words “hard and heavy tidings were ahead.” Churchill’s moments of depression, “the black dog,” as he called them, were not a part of his personality that was often on display, even to his own children (Mrs. Churchill was more familiar with these moods), but this was not one of them. It was among his remarkable qualities that he could look into the pit without blinking, or losing courage. He did not believe we would lose the war, but he would not conceal from his countrymen that it could happen, or disguise from them just how terrible the consequences would be.

For the first time it was clear to those who listened to Churchill’s speech—and the whole country listened carefully—that all of the easy presumptions that had shored up appeasement, among them belief in the French Army, the legendary strength of the Maginot Line, the fighting qualities of the BEF, above all the hope that a deal of some kind might be made with Hitler at the last moment, were all swept away by his stark realism, and by the fact, now suddenly clear, that across the Channel a huge, historic battle was being fought—and would very likely be lost. It is no accident that J. R. R. Tolkien’s The Lord of the Rings took on its length and dense sweep as an epic in that year, with its central vision of the Dark Lord Sauron’s legions attacking an idyllic land not unlike Britain, as the apparently invincible armies of Hitler swept over one European country after another, taking familiar places that the British, the Belgians, and the French had fought and died for in the 1914–1918 war, ports that were well known to anyone who had ever traveled to “the Continent,” and approached the English Channel itself, advancing swiftly toward the port city of Boulogne, where Napoleon himself had once stood, waiting for the moment to launch 200,000 men at England.

It is an indication of just how seriously Churchill viewed events that at nearly midnight of May 20, the day after his great speech to the nation and his personal message to Roosevelt, he perspicaciously told the War Cabinet that he thought as “a precautionary measure the Admiralty should assemble a large number of small vessels in readiness to proceed to ports and inlets on the French coast.”

_________________________

* This is the affectionate diminutive of my father’s name in Hungarian. Vince, Vincikém; Zoltan, Zolikám, etc.