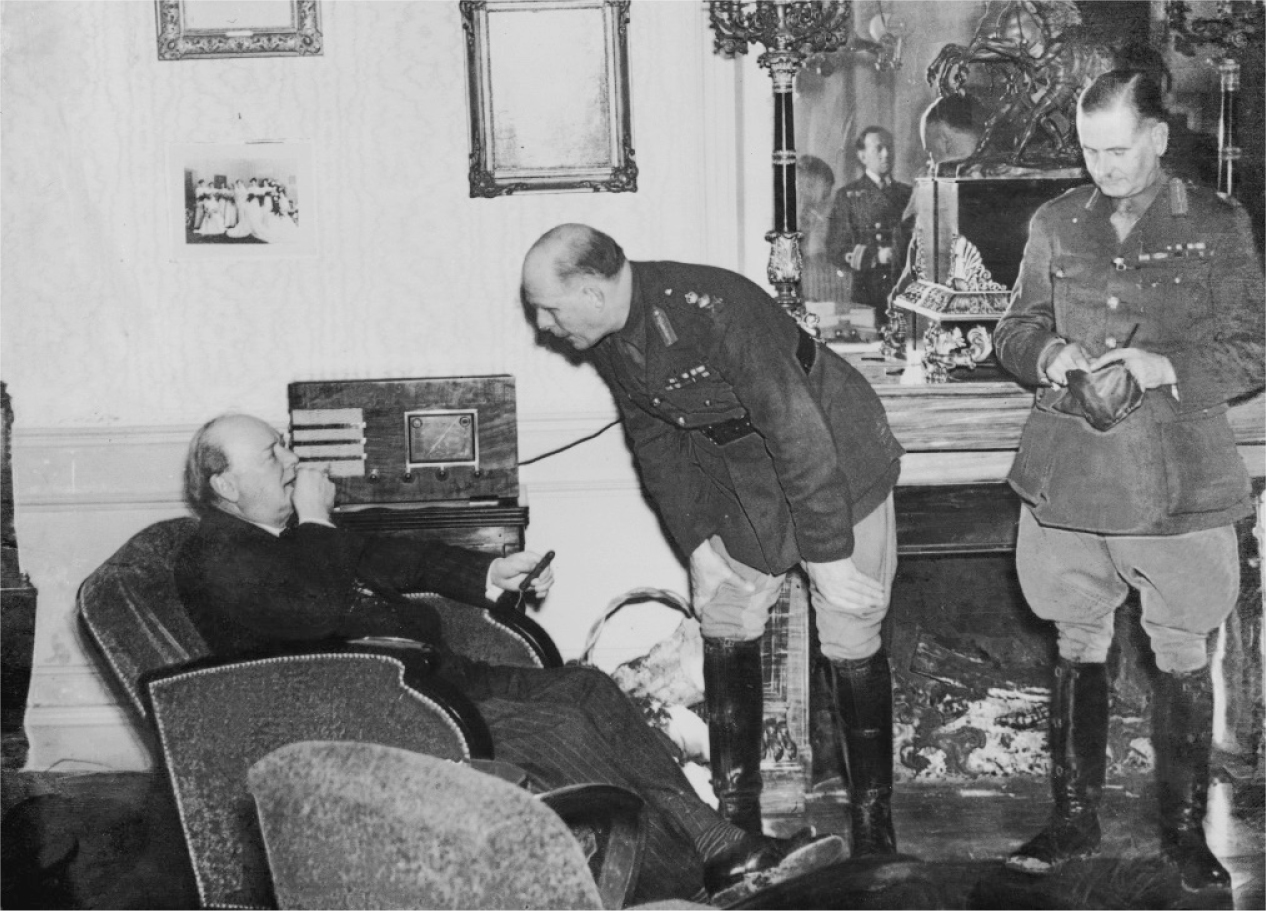

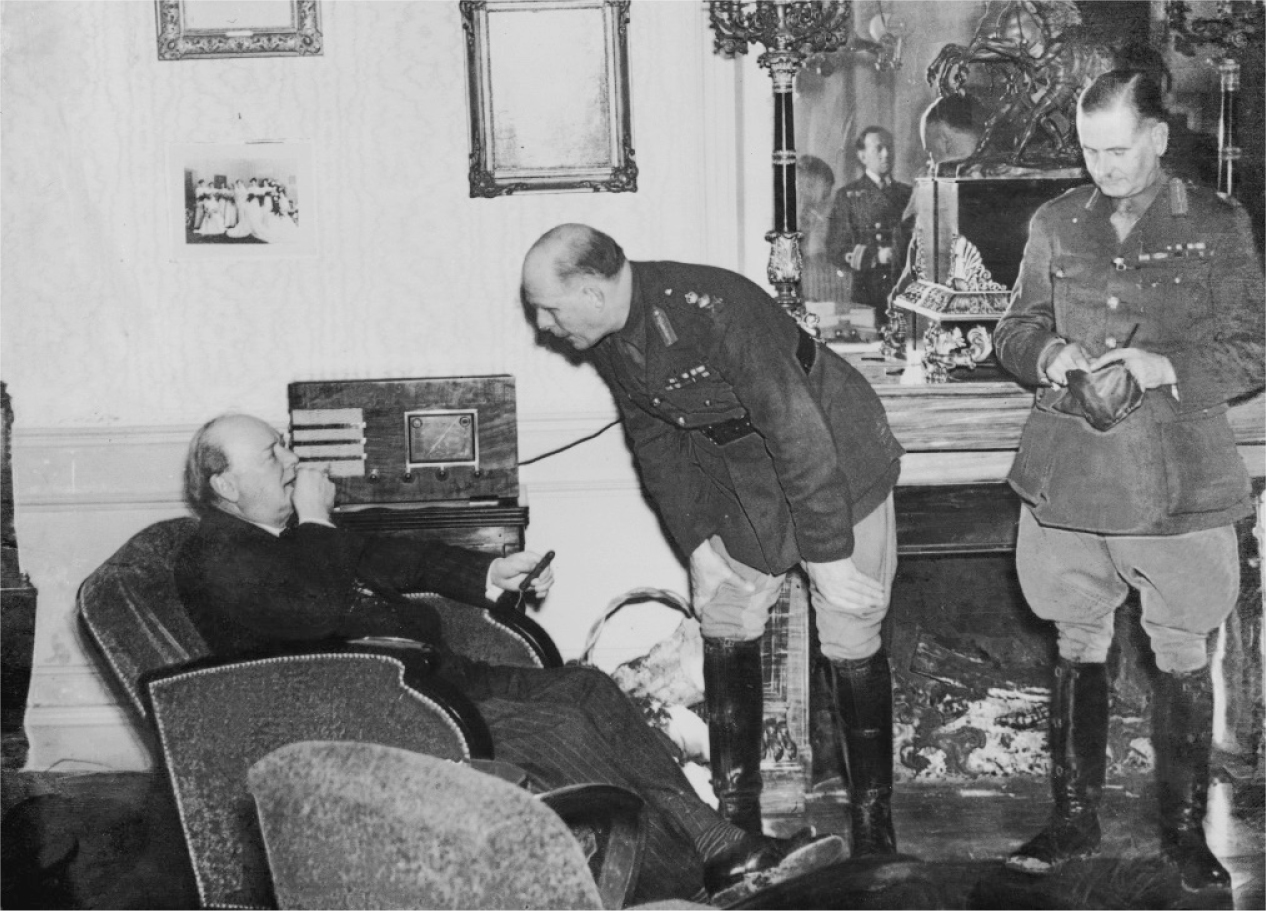

Churchill, Lord Gort, and Pownall.

The Battle of Arras:

“We May Be foutu”

Churchill, Lord Gort, and Pownall.

THERE IS NO way that the 12th Lancers could have known that their fate was being determined as part of a major discussion of strategy taking place between the War Cabinet in London, the French government, the Grand Quartier Général, and the headquarters of the British Expeditionary Force. Lieutenant-General Pownall, who recorded with satisfaction on May 20 that British infantry had repelled several German attacks around Arras “with the bayonet,” also predicted that if a vigorous counterattack was not carried out successfully the next day, “we may be foutu.”*

Pownall had already communicated this dire view of the BEF’s situation through the proper channels to General Ironside, chief of the Imperial General Staff, who had presented it to the War Cabinet the day before, where it was vigorously opposed by the prime minister—perhaps explaining why Pownall, though he went on to fill many important staff posts during the rest of the war, never rose above the rank of lieutenant-general. Churchill insisted instead that the BEF “must fight its way southwards towards Amiens to make contact with the French,” although how this was to be squared with the fact that two corps of the BEF were fighting tooth and nail to hold Arras, nearly fifty miles northeast of Amiens, or that German tanks were already reported to have arrived in Abbeville, at the mouth of the Somme River, well behind and to the right of the BEF, was not explained either by the prime minister or by General Ironside, who should have known better. It was all very well to argue, as Churchill did, against “the proposal to fall back on the Channel ports,” but short of a miracle the BEF—together with what remained of the Belgian Army on its left and substantial remnants of the French First Army to its south—was about to be cut off on three sides with its back to the sea. As for the Channel ports, once the German panzer divisions reached Abbeville, they had only to turn east and roll them up one by one, first Boulogne, then Calais, then Dunkirk. The BEF would be lucky to reach one of them before the Germans did. In the event it was only by perhaps the biggest German mistake of the war that the BEF would reach Dunkirk, less than fifty miles away to the north.

Even the hint that the BEF might be hurled off toward Amiens dismayed the Belgians, who would either have to advance in tandem on the BEF’s left, for which they had neither the vehicles nor the stomach (they would, after all, be moving away from their own country), or be left behind on their own, on the line of the Escaut River, which they could hardly hope to hold for long. Admiral of the Fleet Sir Roger Keyes, Churchill’s personal liaison with the king of the Belgians, passed on the king’s growing alarm and was sternly ordered to keep His Majesty in line. “Essential to secure our communications southward . . . ,” Churchill cabled back to Keyes. “Use all your influence to persuade your friend [the king] to conform to our movements. . . . Belgian Army should keep hold of our seaward flank. No question of capitulation for anyone.”

Looked at on a map, the “bulge” of the German armored thrust was less than thirty miles wide, so it is easy to see why it appeared possible, looking at a map in London, that a concerted attack eastward by the French Third Army toward Amiens and Bapaume, and by the BEF attacking southwest from Lens to join them, could meet in the middle, sever the German line of communications, and reconnect the Allied armies of the north with those farther west and south.

This was also the substance of the so-called Weygand Plan, which Weygand had adopted almost at once upon replacing General Gamelin as commander in chief on May 20. So urgently did General Weygand view the importance of this plan that he set off early the next morning to meet with the king of the Belgians, Lord Gort, and General Billotte in Ypres, against the advice of Premier Reynaud and Marshal Pétain, who feared for his safety. Communications between Paris and the armies of the north were by then almost completely cut off—the Germans had severed the telephone cable at Abbeville, and Weygand’s original intention of making the journey by train and then by car had proved impossible, so that it was necessary to improvise an early morning military flight from Le Bourget airport to Béthune, with a fighter escort. None of that happened as planned; instead the journey was fraught with difficulty—a warning sign that the organization of the Allied armies and air forces was rapidly falling into chaos.

The commander in chief, after innumerable adventures, landed at a deserted military airfield accompanied only by his aide-de-camp. The telephone there had already been cut and there was no car to meet him.† He managed to commandeer a military truck and head out in search of a post office along “roads [which] were already encumbered by Belgian and French refugees, who were dragging along every sort of wheeled conveyance, loaded pell-mell with women and children and animals and all they had been able to save in haste from their homes.” Despite the “disorder and panic” of fleeing Belgian soldiers who had abandoned their weapons and joined the civilian refugees blocking the roads, Weygand at last managed to reach a post office with a working telephone to pass on a message to General Billotte, and after sitting down at a country inn next to the airfield and ordering an omelet he flew on to Calais, where his aircraft managed to land just after the airfield had been bombed and the hangars destroyed.

He did not reach the ornate medieval Town Hall at Ypres until three in the afternoon, which means that the commander in chief of the Allied armies had by then been completely out of touch with events (and his own government) for over nine hours. Even a seventy-three-year-old man as spry as General Weygand must by then have been suffering from days of exhausting, risky, and uncomfortable air travel from Beirut to Ypres.

Learning at the Town Hall that the king was delayed by the crowds of civilians (and of his own soldiers) blocking the roads, Weygand took the opportunity to chat with members of the Belgian government waiting in the splendid Gothic lobby of the building (including M. Paul-Henri Spaak, minister of foreign affairs, and future secretary-general of NATO), and with his quick intelligence soon learned that the king and his government were at odds. The government was in agreement with the Weygand Plan; the king was reluctant to leave the small corner of Belgium he was in, or to order his army to do so. Once the king arrived, accompanied by General van Overstraeten, his Panglossian “military secretary,” His Majesty made it clear to Weygand that the Belgian Army was in no state to cooperate with the French and British attack; indeed it was only with great reluctance that the king eventually agreed to draw his army back from the Escaut to the Lys River in order to cover the left flank of the BEF as it attacked. Weygand, like Lord Gort, actually wanted the Belgians to withdraw even farther back, to the Yser River, which would have given all three armies a straight line to defend close to the Franco-Belgian border, but the king believed that his army would disintegrate if it were ordered to retreat that far, giving up the important cities of Bruges and Ghent and all but a tiny sliver of Belgium. Conversation between Admiral Keyes and Weygand was strained. Weygand did not speak English, and Keyes’s French was so halting that Weygand had great difficulty understanding him. The fact that no interpreter was present also points to the chaos surrounding the Allied commanders. If Weygand was going to communicate with General Lord Gort and Lieutenant-General Pownall, how was he to do so without an interpreter? But none had been provided.

In the event, this problem did not arise. The exhausted General Billotte finally arrived, the “fatigue and anxiety” on his face evident even to General Weygand, but there was no sign of General Lord Gort. Jean-Marie Charles Abrial, the pugnacious French admiral who was in command at Dunkirk, appeared with the news that the Calais airfield had been bombed again, and would soon be unusable. It was apparent by now there was some danger that the Allied commander in chief himself might soon be trapped in Flanders and find himself unable to return to Paris, so Weygand ordered his aircraft and its escort to fly back to Le Bourget at once, and accepted Admiral Abrial’s offer of a motor torpedo boat to take him from Dunkirk to Le Havre.

Even this journey was not without incident. Dunkirk was already being heavily bombed, the pilings that lined the channel to the sea were on fire, and one of its oil storage tanks was sending thick black smoke into the air. To steer a course that was clear of mines the motor torpedo boat had to put in at Dover, then proceed from there to Cherbourg instead of Le Havre because a new minefield had been laid in the Seine estuary during the night. Weygand did not arrive in Cherbourg until five in the morning.

Weygand might have spared himself the exhausting trip from Paris to Ypres and back. He felt “a very lively regret at having failed to meet Lord Gort,” with good reason, but Gort had not been informed of the meeting until late in the day, and even then with no mention of the time. He had been delayed during a visit to the front, where he had made the decision to withdraw the BEF from the Escaut River back to the French frontier, so it was left to General Billotte to explain General Weygand’s plan to him.

Judging by Lieutenant-General Pownall’s record of the meeting, Billotte did not put forward the idea of an attack against both sides of the German “bulge” as firmly as Weygand might have done, nor did Gort point out that he was about to begin an attack of his own south of Arras with two divisions of infantry and the last of the BEF’s tanks.‡ Gort also does not seem to have made it clear that the BEF, with its supply lines to Le Havre and Cherbourg now cut, was reduced to three hundred rounds per gun, that its supply of small arms ammunition was running low, and that even at half rations there was only enough food left for four days—still less that the alternative to a victory at Arras was to fall back on Dunkirk and attempt to evacuate the army, the only Channel port left since the Germans had already taken Boulogne and German tanks surrounded Calais. Billotte may have been overwhelmed by the problems of the French First Army as well by his own new responsibilities toward the BEF and the Belgian Army—he had not issued any orders to Lord Gort for over four days, or even attempted to make contact with him, so he may not have been fully aware of the BEF’s perilous position, or able to take in what Gort told him. Unless Pownall’s notes are at fault, Billotte and Gort did not make much of an impression on each other at all. If Weygand and Gort had been able to meet, it might have made some difference to the course of events. Weygand, if nothing else, was energetic and realistic, and Gort was combative by nature, poor Billotte was neither.

What does come through clearly in Pownall’s notes is the pessimism of the king of the Belgians, who pointed out sharply that once Gort had withdrawn the BEF from the Escaut, the Belgian Army would have no option but to fall back to the Lys River, like it or not. The king had already made it clear that “the Belgian Army existed solely for defence, it had neither tanks nor aircraft and was not trained or equipped for offensive warfare,” something that neither the British nor the French government wanted to hear. In the absence of General Weygand, General Lord Gort had no idea that the Belgian government was already at odds with their King.

As for General Billotte, he had already given his opinion that the French First Army was “incapable of launching an attack, barely capable of defending itself,” and it is unlikely that anything he heard from General Weygand or Lord Gort would have been likely to change his mind. What he thought of the results of the meeting at Ypres is impossible to know since his car was involved in an accident on the way back to his headquarters injuring him so severely that he never regained consciousness and died two days later.

Thus, what was probably the last chance for a concerted reaction to the German advance from the Allies had come and gone by the end of May 21. Broad and sweeping proposals for stopping the Germans would continue to be issued from London, and received with increasing skepticism and impatience by the French government, but the two principal commanders in the field had failed to meet and agree on a plan, and the BEF now had supplies left for only one more battle, at best.

It would change the course of history in the most unexpected way.

* * *

Although General von Manstein’s plan for Fall Gelb had worked just as he had said it would, the rapid advance of the German panzer divisions to the Channel coast continued to cause anxiety, as well as dissension between General Guderian and everybody above him in the German chain of command. On May 20 General Halder noted the importance of turning Kleist’s panzer group toward the south as soon as possible, a reflection that OKH (and possibly Hitler) were more concerned with developing a full-scale attack to defeat the French Army as a first priority, rather than dealing with the “pocket” containing the BEF, the French First Army, and the Belgian Army. To Guderian, every attempt to slow down the panzer divisions on their way to the sea was a mistake. Once he had reached Abbeville on May 20 and cut the BEF’s main line of communications and supply, he was determined to turn east and cut off any possibility of its “retreat to the sea.” Like a horse being pulled back by its own jockey just as it approaches the finish line in the lead, he sensed the magnitude of the victory that was just within his grasp.

Better than anyone, Guderian understood that the rapidity of the German armored attack had literally paralyzed the French Army—the mere approach of German tanks was enough to make whole regiments abandon their line and their weapons and retreat. On the German side, the fear that the tanks must slow down or stop to let the mass of the German infantry catch up with them was baseless—the tanks had achieved a psychological victory over the French that was out of all proportion to the number of tanks involved, or to the relative merits of French and German armored vehicles and each side’s antitank weapons. The mere idea of the approach of German tanks, let alone their actual appearance on the battlefield, not only undermined the morale and the fighting spirit of French soldiers but was enough to unhinge their commanders, whose training and commitment to a defensive war left them unable to deal with one in which fixed lines no longer had any meaning. The paralysis that had gripped General Billotte already before his fatal accident had spread to other senior commanders, even to General Georges, who also seemed bewildered by the swift pace of events.

The truth of Napoleon’s remark that “with victory comes the most dangerous moment,” was about to be demonstrated again, in the form of the British counterattack at Arras, which took Major General Rommel, of all people, by surprise. Rommel had captured Cambrai without any great degree of difficulty, and no doubt expected to take Arras, about twenty miles northwest, without meeting much opposition. Instead he collided with what had been named Frankforce, after its commander Major-General Harold Franklyn, intended to relieve the German pressure on Arras, which had been for seven months the home of the headquarters of the BEF.

Only sixty-five miles from the English Channel, Arras was not only a good-sized city and a transportation hub but also “high ground” in an area noted for its flatness. As always in military matters this is relative, the rise on which Arras is built is not more than 123 feet above sea level, but that was sufficient to make Arras the focal point in May 1917 of a five-week battle that cost the British almost 160,000 casualties during the course of which the city was largely destroyed, and it was enough to attract the attention of Hitler in May 1940.

The Führer opened his working day at eleven every morning with a prolonged examination of the military maps, flanked on one side by the slavishly sycophantic General Keitel, chief of the OKW, and on the other by the stiff, no-nonsense General Halder, chief of the OKH,§ no doubt biting his tongue; the latter’s task was to translate Hitler’s thoughts about the battle in France into the rigid language of operational orders, and when possible to provide a measure of stern professional caution and advice. On the need to seize the high ground at Arras, Hitler and Halder were not in disagreement—nor was Rommel.

Hitler helps himself to soup in the field.

Although Lord Gort does not get much credit for it, he was determined to hold on to Arras for the same reason that the Germans were determined to take it, and perhaps more important had come to understand that as the German armored divisions rushed ahead, the infantry divisions advanced in what resembled a relay race to defend their flanks. If he could find a gap between the tanks and the infantry, he might be able “to insert a wedge into the gap,” cut off the German armored divisions, and destroy them. The place at which he chose to do this was Arras, which had already been holding out for four days against constant enemy attacks, but given the time pressure he could only put together “a scratch force” consisting of the 6th and 8th Battalions of the Durham Light Infantry and what remained of the 4th/7th Royal Tank Regiments—not more than two thousand men and seventy-four infantry tanks, of which only sixteen were Mark II infantry tanks with a gun powerful enough to engage the latest German tanks. Like the Mark I, the Mark II Matilda was slow, heavy, cumbersome, and prone to mechanical and track failure, but against its thick, three-inch armor the ordinary German 37 mm antitank rounds simply bounced off harmlessly, which had a disconcerting effect on German antitank gunners.

Rommel had managed to get within two miles of Arras on the night of May 20, as usual leading from the front, only to find that his motorized infantry was too far behind to support the tanks. He set off to find them in an armored car and discovered that a few tanks from a French light armored division had “infiltrated his line of communication.” He managed to sort all this out during what remained of the night and the next morning, and even to bring up some of his artillery, but he was not able to resume his attack until about three o’clock in the afternoon of May 21, with the 7th Panzer Division advancing toward the east of Arras, supported by the motorized infantry division SS Totenkopf on its left.

The SS Death’s Head Division was among the first of the Waffen SS units to see combat, but the SS troops had not yet acquired a reputation as “elite” soldiers, indeed their level of discipline, training, and armament was still considerably inferior to that of the best army divisions. They were there for political reasons, and through a complicated series of compromises fought under army command while still retaining their link to SS Reichsführer Heinrich Himmler. Many of their older officers and NCOs were World War One veterans, but while the SS troops were eager to prove themselves in battle and were brave to a fault, at this point in the war they lacked the iron discipline¶ and steadiness of German Army regulars.

Heinrich Himmler, with his daughter Gudrun.

Rommel had “put his Armored Reconnaissance Battalion in between the Panzer Regiment, forming the spearhead, and the Rifle Regiments behind,” in order to secure the road and prevent a dangerous gap from forming between the armor and the infantry, but despite this his infantry was once again slow to come up, and Rommel had to go back to “chase up” the infantry. This was exactly the kind of gap into which Lord Gort had hoped to drive a wedge.

Rommel was therefore not in the lead among his tanks, his preferred position in battle, when the first tanks of Frankforce appeared, exactly where they were supposed to, near the village of Wailly on the outskirts of Arras between the German tank force and the bulk of its infantry, almost catching Rommel and his aide-de-camp Lieutenant Most in the open as they attempted to sort out a traffic jam of infantry, and causing chaos among the scattered vehicles of the German infantry regiments. Rommel and Most managed to restore order and bring artillery to bear on the British tanks, running up and down under heavy fire to give each gun its target. The British attack was turned back, but Most was killed while standing beside Rommel, and only a couple of miles away the German antitank gunners, shaken by seeing their shells bounce off the Mark II Matildas, were overrun by British tanks, the line of German antitank guns and their gunners crushed by their tracks. During the confusion of the battle, the troopers of SS Totenkopf were pushed back in retreat, a humiliation that would soon have bitter consequences.

Rommel eventually managed to stop the British tank attack with his field artillery and the 88 mm antiaircraft guns that would remain the most formidable of German artillery weapons throughout the war, and by the early evening had managed to organize a tank attack against the rear and the flank of the British armored force. “During this operation the [25th] Panzer Regiment clashed with a superior force of enemy heavy and light tanks. . . .” Rommel wrote. “Fierce fighting flared up, tank against tank, an extremely heavy engagement. . . .” By nightfall fighting had ceased, for the moment the British and French still held Arras, but Frankforce had lost sixty of the eighty-eight British and French tanks engaged, thus depriving Lord Gort of most of his remaining armor.

The repercussions of the Battle of Arras, as it came to be called, were immediate. As the most dashing and self-confident of panzer commanders, Rommel was not accustomed to being stopped or slowed down. He attributed his problems before Arras on May 21 to having been attacked by five enemy divisions, not a mere two battalions of infantry, two below-strength British tank regiments, and a small number of French Somua tanks. What shocked him was the fact of the enemy attacking instead of retreating before his tanks, as well as the thick armor of the Mark II Matildas. As the news about his check at Arras made its way up the German chain of command, it reinforced the skepticism and doubt of more-senior commanders about Guderian’s “race to the sea.” Conventional wisdom had always been that the tanks must stop and wait until the infantry and artillery caught up with them, and Rommel had now demonstrated in the view of older and wiser heads the truth of this.

The fact that Guderian’s panzer divisions had just taken Abbeville, effectively severing the BEF’s line of communications, seemed less important than Lord Gort’s attempt to separate Rommel’s infantry from his tanks, and the fact that SS Totenkopf, supposed to be the toughest of the tough, had broken and run as the British tanks crushed the German antitank guns and their crews, came as a shock to the SS and party leadership.

A certain caution made its way back—Kleist passed his concerns up to General von Kluge, who passed them on to Colonel General von Rundstedt, commander of Army Group A, and from there to General Halder and the Führer. The consensus was that the advance westward should be halted until the situation at Arras had been “cleared up.” Even Halder, Guderian’s fiercest supporter, notes with a degree of caution, “The decision will fall on the high ground of Arras,” although Rommel had already shattered the British attempt to hold it.

General Gerd von Rundstedt.

Seldom has such a quick and triumphant victory produced such a moment of hesitation and caution in the victors. It led to one of the decisive mistakes of the war.

_________________________

* foutu = fucked. General Pownall followed the delicate English tradition of putting obscenities into French in his diary.

† His cars, each equipped with a siren and the flashing lights of the commander in chief, had been sent off by train during the night and were nearly captured by the Germans at Abbeville, another sign of growing dislocation.

‡ This consisted of the remainder of two battalions of obsolete Mark I and Mark II “Matilda” Infantry tanks suffering badly from “track trouble,” since they had to “waddle” all the way back from Brussels because of the striking Belgian railwaymen’s refusal to load them onto flatcars. The “I” tanks had not been designed with road travel in mind.

§ The OKW was the high command of the German armed forces, the OKH the high command of the German Army. Keitel was a military bureaucrat, Halder the exacting high priest of the fabled German general staff.

¶ Sometimes referred to as Kadavergehorsam, i.e., the obedience of a corpse.