British Bren Gun Carriers advancing as Belgian civilians flee.

“Their Zest and Delight in Shooting Germans Was Most Entertaining”

British Bren Gun Carriers advancing as Belgian civilians flee.

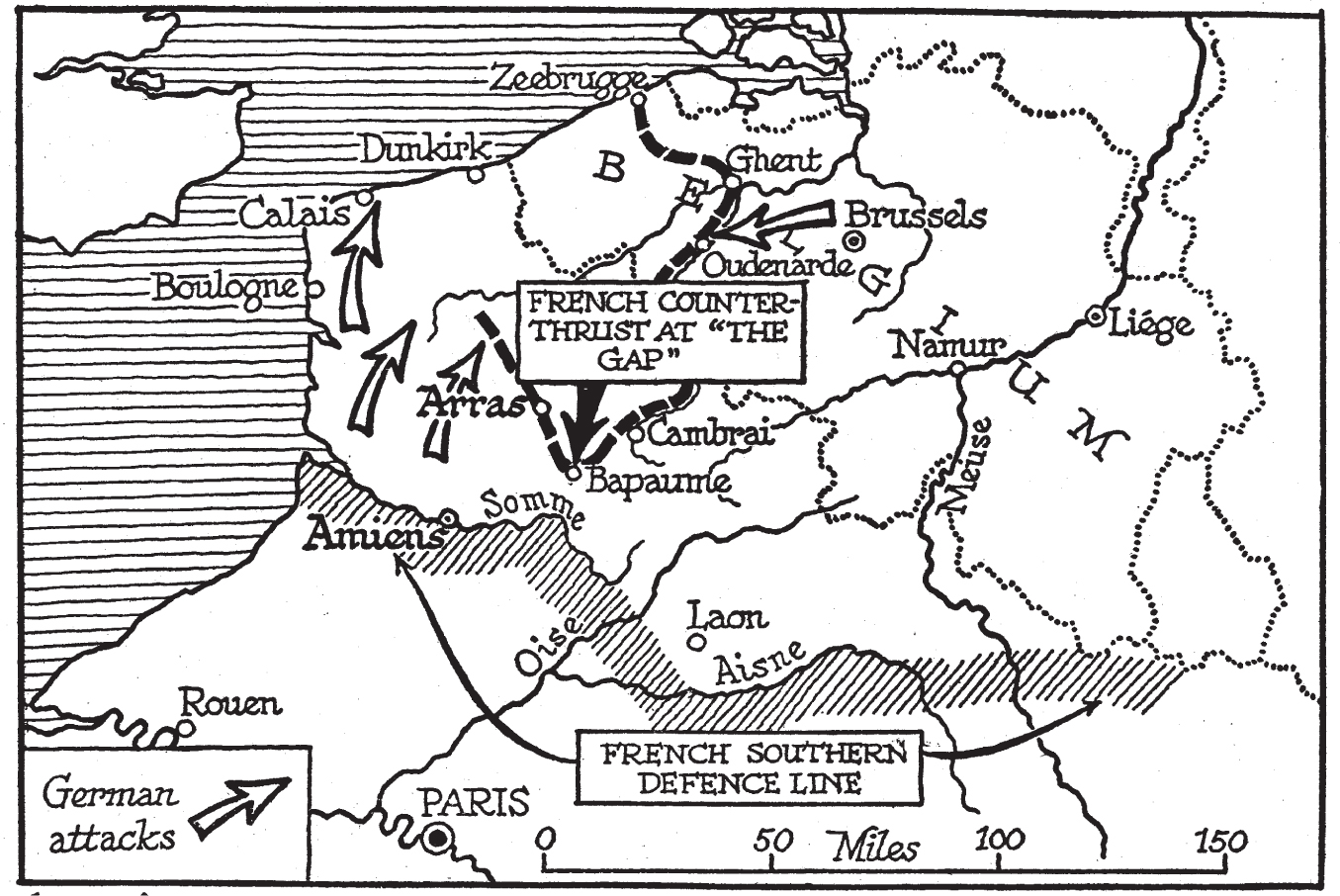

“THE BATTLE OF Arras has been . . . a most gallant affair,” General Pownall noted in his diary on May 22, while qualifying that statement a few lines further down. “We are now tactically in an impossible position,” he wrote, an opinion that would not have been shared by the prime minister, had he known about it.

German troops entering Ypres.

On the same day Churchill flew to Paris early in the morning to consult with the French government. The atmosphere was somewhat less panicky there, now that it was clear the German armored columns were making for the Channel rather than for Paris. Churchill and Reynaud were driven to GQG at Vincennes, where General Weygand made an immediate good impression on Churchill, who found him “brisk, buoyant and incisive,” despite Weygand’s difficult twenty-four-hour journey to Ypres and back—despite also the gloom that tended to affect everyone who visited the sinister, ancient fortress where Henry V had died and the Duke of Enghien* was executed. At one moment, the prime minister looked out the window and saw a group of officers, presumably the remnants of Gamelin’s staff, “pacing moodily up and down” in the courtyard. “C’est l’ancien régime,” remarked one of Weygand’s aides standing beside him.

Weygand, the nouveau régime, commanded respect not only by his spry appearance for a man of his age but by his energetic and fluently expressed plan of attack, which happened to coincide with the opinions of the prime minister. Weygand too believed that Boulogne, Calais, and Dunkirk could be held with the forces already there—although his visit to Calais and Dunkirk the day before should have made him more cautious on that subject—and that a full-scale British attack “in the Cambrai and Arras area and in the general direction of St. Quentin,” covered by the Belgian Army to the east, should meet a French attack from the southwest and cut off the German armored divisions. The fact that the king of the Belgians had already expressed strong doubt that his army could do that—and that Lord Gort had just made an attack at Arras that had cost him most of his remaining tanks—was simply not mentioned. On the contrary, the prime minister returned to London invigorated by Weygand’s performance, and sent Lord Gort an order that “the British Army and the French First Army should attack southwest towards Bapaume and Cambrai at the earliest moment—certainly tomorrow, with about eight Divisions—and with the Belgian Cavalry Corps on the right of the British.”†

“Here are Winston’s plans again,” complained General Pownall after receiving this order. “Can nobody prevent him trying to conduct operations himself as a kind of super Commander-in-Chief?” Pownall remarked that at this point the BEF’s reserve consisted of “only one cavalry regiment,” and not merely asked where the Belgian Cavalry Corps was but doubted (correctly) that it even existed for any practical military purpose.

The BEF was still holding a long front on the Escaut, Pownall wrote, “defensive posts [were] manned by many old people, the ‘labor’ Territorial divisions, R. E. [Royal Engineers] construction companies, anyone we can lay hold on thrown together. . . .” Many of these troops had not been issued rifles (they had been sent there to dig, not to fight), and those who had one had received no training in marksmanship. Supplies of small arms ammunition had now dropped so low that Lord Gort had urgently requested the RAF to drop SAA by air, which the RAF was unable to do because of German air superiority over the battlefield, and even on half rations the army was reduced to three days of food.

There was still no sign of an attack from the French Third Army from the Somme toward Arras and Cambrai intended to meet the BEF halfway, as Weygand had promised. Chief of the Imperial General Staff Tiny Ironside in London remarked in his diary that despite Weygand’s energetic presentation of his plans, the French effort was “still all projets,” implying elaborate, polished staff preparations for attacks that would never take place, a constant complaint that the British generals made about French staff work, which always seemed unconnected to the facts on the ground, as if faultless staff work were a reward in its own right.

“I am trying to square up this end to clear the Channel ports for Gort,” Ironside added significantly, demonstrating the divergence between the prime minister’s view of things and that of his chief military adviser. In Churchill’s mind, the BEF was about to attack with eight divisions to meet up with a French attack; in that of Generals Ironside, Dill, Lord Gort, and Pownall the only hope of saving the BEF was to order a fighting retreat to Dunkirk and hope that the navy, aided by the RAF, could get at least some of the troops home to England, surely not all of them, and certainly without any of their equipment—tanks, armored cars, vehicles of every kind, guns, supplies, all of this would have to be destroyed or abandoned, nothing on this scale had ever happened in the history of the British Army, not even at the evacuation of Gallipoli in 1915, or the evacuation of Sir John Moore’s army at Corunna from Spain in 1809 after his heroic death. “We buried him darkly at dead of night, the sods with our bayonets turning. . . .” One of the most famous poems in the English language—for some reason most boys used to memorize it in school—commemorated that defeat, but on May 22, 1940, nobody could anticipate that a British evacuation from Dunkirk would become an epic, even if it could be carried out, which seemed improbable.

By the next day the prime minister’s “buoyant spirits” created by his brief trip to Paris had begun to subside. The minutes of the War Cabinet on the morning of May 23 reflect a grimmer note of reality. “The whole success of the plan agreed with the French [only the day before] depended on the French forces taking the offensive. At present they showed no sign of doing so.” The prime minister, in the spirit of a man who has fallen head over heels in love and then discovered that the object of his affection hasn’t done what she promised, quickly dictated a blistering telegram to Premier Reynaud, demanding that “French Commanders in the North and South and Belgian General Headquarters be given most stringent orders to carry this out and turn defeat into victory.”

The chances of any of this being carried out were zero (it was received with a weary shrug in Paris), and some recognition of this apparently entered the prime minister’s mind, since almost immediately after sending a scorcher to Reynaud he brought up the subject of making a “plan with the object of saving and bringing back to this country as many of our best troops and weapons with as little loss as possible.”

A further grim note to that day took place at seven in the evening when Lord Gort gave what remained of the two British divisions in Arras the order to withdraw at once before they were surrounded, thus squeezing the BEF into a “pocket” less than fifty miles deep and thirty miles wide. To its south was the French First Army, now under the command of General Blanchard, only slightly less ineffectual than the unfortunate General Billotte; to its east was what remained of the Belgian Army; to the west, along the narrow Aa River and the Canal du Nord, neither of them a significant military obstacle, were the German panzer armies and the infantry trying to catch up with them.

Lord Gort may not have fully realized that by his timely decision to abandon Arras he would set off an angry row between the British and the French governments that would still be going on long after France had surrendered. Inadvertently, he had given Weygand one of the two excuses he needed for placing the blame for France’s military disaster on the British—the withdrawal from Arras and the reluctance of the British to commit the bulk of the RAF fighter squadrons to France would become a constant refrain at every meeting between the two governments.

The former was a sensible decision given the absence of evidence that a French attack existed except as a projet on paper at GQG; the latter would prove decisive during the Battle of Britain, which began two months later.

On the ground, fighting was intense, and bombing relentless, all the more terrifying as the noose around the BEF and the French First Army was pulled tighter, reducing the territory for both the armies and the civilians. The 12th Lancers had been ordered to make an attack toward Arras to help secure the withdrawal of the two British divisions there. Henry de La Falaise, with the 12th Lancers, described the chaos surrounding them on May 21: “The stampede of refugees has now become a matter of life and death for us. They must not be allowed to go on blocking the roads and impeding our movements. . . . Twice I have to pull out my revolver and threaten the peasants to make them turn back. These unfortunate people are frantic. They have fled southwards to escape the invader and have bumped right into him again. . . .”

He watched as German bombers, sixty of them at a time, saturated the area: “The earth rocks under incessant explosions and the atmosphere vibrates with the roaring of their motors.” All around him were scenes of horror, dead refugees, dead and dying farm animals, British and French armored cars trying to make their way through the terrified mob, burning farms and villages. By evening the 12th Lancers were ordered to move northwest—their attack was canceled—with the even more dangerous job of finding just how far German tanks had reached.

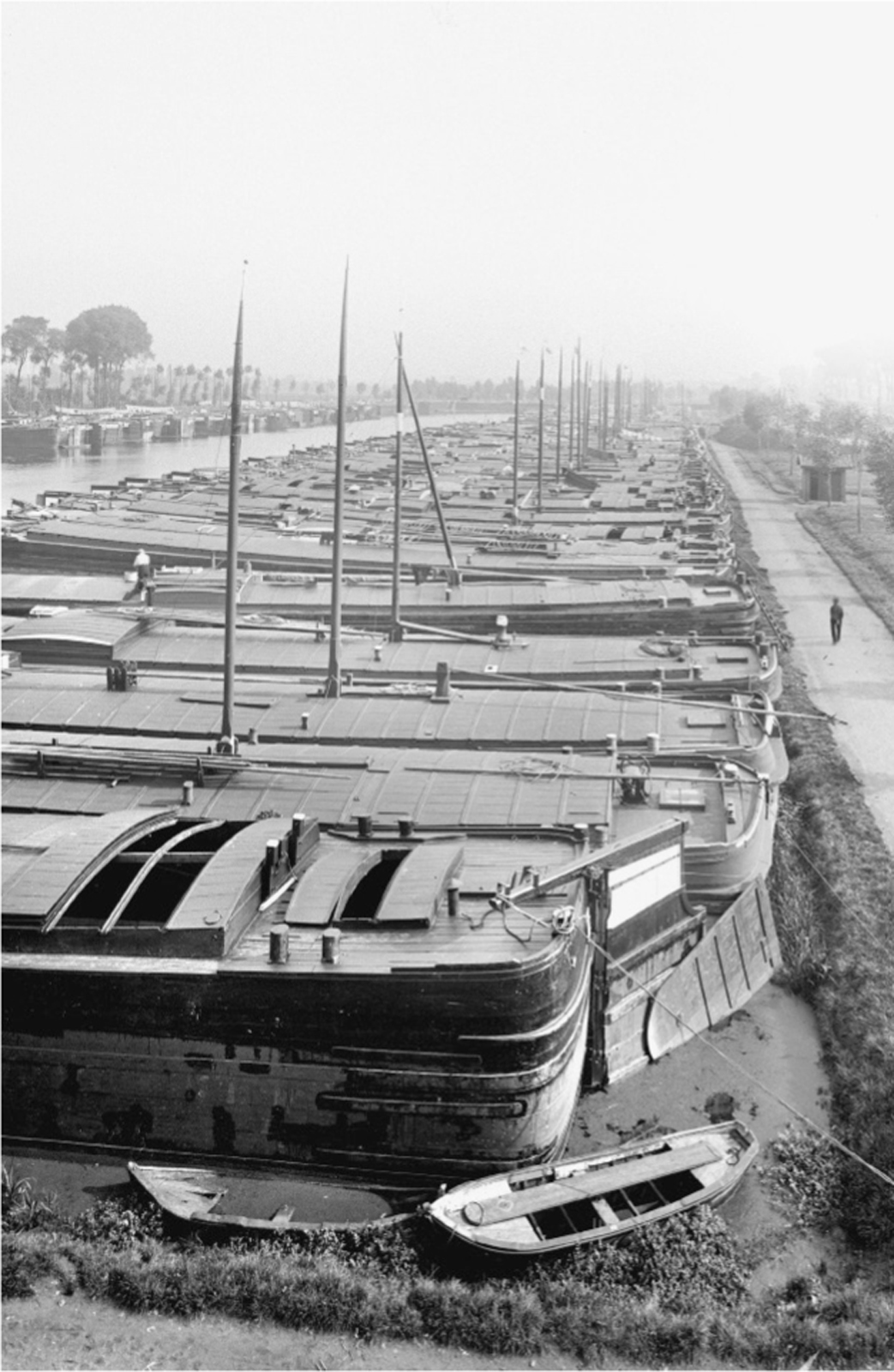

Barges on a Belgian canal.

Throughout the day on May 22 they were bombed, strafed, and shot at by German tanks. Two more of the armored cars were destroyed, several men killed, the commanding officer and one of the troop commanders wounded, the latter fatally. That night La Falaise bedded down on the floor in a deserted village café, with the sky illuminated by the city of Béthune in flames, kept awake by “tremendous” explosions as the Royal Engineers blew the bridges over the Aire Canal one by one.

An even closer view of the BEF in crisis was written by Arthur Gwynn-Browne, a lance-corporal in Field Security Personnel, attached to GHQ. Gwynn-Browne joined up in December 1939, at the age of thirty-five (an advanced age to join the army), after a career as a hotel manager. He had been educated at Malvern College, a mid-upscale English boarding school, and at Christ Church College, Oxford. He may have had some pretensions to being upper-class (Christ Church is the biggest and one of the most socially rarefied of the Oxford colleges, and he was for a time master of the Oxford Beagles),‡ but if so he dropped down the social scale sharply from there to provincial hotel keeping and obviously failed to get a commission when he joined the army, perhaps because the only sport he claimed to be interested in was tennis, rather than the obligatory rugby or cricket.

At some point between Oxford and the army he became a devoté of Gertrude Stein, the American-born modernist writer (“Rose is a rose is a rose is a rose”) and cultural figure. In 1939, Field Security personnel were chosen for their ability to speak French, and were supposed to “assess civilian morale,” “test the security of the Army’s installations,” and report on potential saboteurs and enemy propaganda. They were uniformed “snoopers,” rather than apprentice James Bonds, and were equipped with a revolver and a motorcycle, making them rather independent of normal army routine and apt to be arrested themselves by the military police on suspicion of being an enemy agent.

Although Gwynn-Browne’s attempt to write “Cubist” prose can seem puzzling, he was that rarest of observers, a well-educated public school§ Oxonian serving in the ranks. Since much of the time his subunit was attached to General Headquarters, Gwynn-Browne more or less followed its peregrinations as it retreated from one château to another—at one point only hours before the town it was in was taken by the Germans. At the time, the surest way of telling where a British headquarters was located was by the number of motorcycles going back and forth to it—the shortcomings of British wireless communication and the collapse of the Belgian and Pas-de-Calais telephone systems made the dispatch rider, with his leather gauntlets, knee-high buckled boots, and leather helmet a necessary (and vulnerable, being a favorite target for low-flying German fighter pilots) figure on or near the battlefield. The Field Security personnel tended to mess with the DRs rather than with the less sympathetic and more spit-and-polish military police.

Gwynn-Browne saw the retreating French and Belgian troops go by in Avesnes mixed up with the refugees, “with their bicycles, and bedding and bird-cages,” and their broken-down cars, wheelbarrows, and weary horses. Gwynn-Browne even saw a steamroller coming down the street at three miles an hour, pulling two large farm wagons each full of at least thirty old people and children, and “in the end one were two small dogs and attached to the end wagon were two cows walking. . . . For four days and nights from Belgium into France and across northern France at three miles an hour in an open wagon under the black smoke of the smoking chimney in a constant unchangeable shattering noise, this is how these families had lived.”

They were by now going nowhere, the battle was approaching them faster than they could move from it, in fact they were moving into it. The French soon grew hostile toward the Belgian refugees, but Belgian or French they were a constant presence and could not be ignored even by the generals since they “blocked the roads for military movement,” as General Pownall pointed out in vexation. “Everywhere was refugees. Hundreds thousands and hundreds of thousands of refugees . . . helpless, motionless, listless, foodless. . . . I remember wondering so often about them why it was I could not feel some pity,” Gwynn-Browne wrote, but neither did anyone else. There were too many of them to inspire pity, and even when a few of the oldest, the youngest, and the sickest were placed in cattle cars drawn up on the railway, they were left there on the filthy straw by the French without food or water (or a locomotive), then bombed by the Germans despite conspicuous markings of a red cross against a white background on the roof of each car.

The French troops retreating from the failed battle at Sedan were as miserable a sight as the refugees. “They had no arms and were saying that the struggle was hopeless. . . . They said that the Germans were invincible. . . . The streams of refugees were demoralizing enough but at least they kept the inhabitants occupied in attending to their needs. But seeing French soldiers just scattered and adrift was another matter. We found the people sitting in their shops and cafés, crying and hopeless, men as well as women.”

Those drawing plans in London, and even in Paris, were unaware of the tidal waves of misery and defeat washing over an area small enough to begin with that grew smaller every day. The attack of Army Group B had driven the Allied armies in Belgium west to the French frontier and beyond into a part of the country with a bewildering mass of rivers, creeks, and canals, while Kleist’s panzer divisions striking north and west from Sedan pressed them into a rapidly diminishing area, along with hundreds of thousands of civilian refugees from the east and the south unable now to move farther on or to return home without being caught up in the battle, and constantly under attack from the air. All war is hell, as General Sherman—and who would know better?—remarked, but the combination of military defeat and civilian anguish has seldom been as concentrated as this. Although there was a lot of firepower massed in a shrinking area, it was not being used effectively—General Pownall is probably correct that it would have been better to put the BEF, the French First Army, and the Belgians under the immediate command of Lord Gort, who was on the spot and eager to fight it out, rather than leaving it under the remote command of General Georges, who was neither, but to be fair the idea of putting French and Belgian troops under a British commander would have been a hard sell.

Gwynn-Browne caught the feel of it, when he found an obviously new and “huge French gun . . . stranded in a field, its crew indescribably dirty and about forty of them.” An energetic commander in chief might have been able to pull all this scattered manpower and artillery together to some purpose, but no such person was appointed, so they remained three separate armies, each with its own strategy for survival, or surrender.

In one of those rare moments when the opinions of a lance-corporal and a lieutenant-general coincide, General Pownall paints a grim, but doubtless accurate, picture of the situation:

This morning (at 9 a. m.) came news that a party of Germans, with some tanks, were coming at Hazebrouck where Brassard [the code name for GHQ] is situated. We ordered rear Brassard to shift to Cassel where (contrary to last evening’s reports) there are in fact no Germans. But there are also no signal communications. . . . Our spirits rise and fall—sometimes, most of the time, the position seems perfectly hopeless and we are of course working out plans for withdrawal north-west; then the clouds lift a little and there seems just a chance of seeing it through. It’s a wearing existence.

It was worse than wearing for those who were fighting from one river, canal, or ditch to the next—it was an intense and seemingly endless battle against heavy odds. Whatever the larger plans of GHQ or the War Cabinet were, nothing was communicated to the fighting troops but the need to keep on doing what soldiers have always done since the beginning of time. They did not get to see “the big picture,” nor did they need to. They saw only what was in front of them, and apart from that were aware only of who was on either flank of them, and how reliable they might be. The Germans were not an abstraction on the map, or a nuisance like the refugees; they were the enemy at close range, and often the fighting was reduced to the closest kind, rifles, grenades, and the bayonet.

On May 21, the date of General Weygand’s ill-fated fact-finding trip to Ypres, a private of the 2nd Royal Norfolk Regiment,¶ his company pinned down by enemy machine-gun fire near the Escaut River, close to Tournai, Belgium, a historic and oft-besieged city, saw his company sergeant-major, George Gristock, “crawling across this open ground on his elbows with his rifle in front of him. There were at least three other men behind him. They were moving towards a German machine-gun nest in front of them. . . . I saw him putting up his rifle and I heard him fire at least three shots. . . . I remember him reaching back, and throwing grenades.” Gristock had taken command when his company commander was “hit in the guts, the back and the arm” and carried off on a car door ripped from its hinges since there were no stretchers. Gristock set off at once with three men to destroy the enemy machine gun that had wounded his captain and was inflicting serious casualties on the company. In the flat tone of the official London Gazette, in which all military promotions and decorations are recorded, “Company Sergeant-Major Gristock . . . was severely wounded in both legs, his right knee being badly smashed. He nevertheless gained his fire position, some twenty yards from the enemy machine-gun post . . . and by well-aimed rapid fire killed the machine-gun crew of four and put their gun out of action.”

Gristock then managed to crawl back and secure his company’s line despite his wounds, and was eventually evacuated back via the beach at Dunkirk to England, where he died shortly after surgery. For this “gallant action” he was awarded a posthumous Victoria Cross, one of only four awarded in the retreat to Dunkirk.

The official British war history, The War in France and Flanders, 1939–1940, is a chronicle of fierce and unrelenting hand-to-hand fighting to hold a perimeter around the BEF—whether it was going to attack toward the southwest and meet up with a major French attack from the Somme or (more likely) carry out a fighting retreat to the coast. This was a matter for the commander in chief to decide, as well as the War Cabinet and ultimately Winston Churchill, but whatever the decision, the survival of the BEF would depend on the ability of its fighting troops to hold back the enemy and thus prevent the disintegration of the BEF. Once an army begins to collapse into separated units and loses its will to fight, its surrender is certain, merely a matter of time—that process was already happening to the Belgian Army on the BEF’s left, and there was considerable concern about the French First Army, to the south of the BEF, which was showing signs of fatal inertia at the top and weariness at the bottom. This was understandable—the French had borne the brunt of the fighting to the south, and taken heavy casualties, the Belgians had been pushed into a retreat that drove them out of their own country.

Now, on May 22, as the armies abandoned the Escaut and sought to reform along the line of the French frontier, the troops experienced “bitter and confused fighting” all day and long into the night—the 1st/6th Queens, for example, sustained four hundred casualties in two days (over 50 percent), the 1st Royal West Kents had to fight its way out at night, sacrificing most of one company, “thirty-four field guns were lost or destroyed,” since “terrified refugees” blocked the roads that would have allowed the gun tractors to come up and tow them away.

Even privates could see that if the armies could not hold the Escault there was no good reason to suppose they could hold the Lys River, which for much of its length is quite narrow, but there was no dismay. A typical example was that of the 1st Royal Irish Fusiliers, ordered to hold a line of nearly seven miles on the Canal de La Bassée at Béthune, five miles south of the Lys, which would give each company of just over one hundred riflemen almost a mile to hold, an impossible task, indeed the British official history says flatly, “A single battalion cannot defend seven miles.” That, however, was their order, and they set out to do it.

Men of the Royal Irish Fusiliers preparing to defend a house—note the bricks knocked out as firing points, or “loopholes.”

Their approach to the canal was slowed by a “seemingly limitless mass of piteous, weary, uprooted people,” including “a demented young mother whose ailing child had died on the roadside,” children of all ages separated from their mother, and old men and horses who had collapsed in the middle of the road, sights so lamentable that even hardened soldiers would have stopped to help if they had not been ordered on firmly by their NCOs.

The canal itself, when they reached it, was narrow and had high banks on either side, making it difficult to defend without heavy digging, all the more so since their section of it was full of several hundred large canal boats that the Germans could make use of to cross over the canal even once the Royal Engineers had blown up all the bridges. In the end, the fusiliers had to send back for gas to set fire to the wooden barges and for explosives to blow up the steel ones, neither of which methods proved all that successful, since the canal was fairly shallow and the hulks merely settled on the bottom.

The fusiliers were too few to hold the Germans back for long, but they attracted a mixed force of retreating men and NCOs of the 4th/7th Dragoon Guards, the Argyll and Sutherland Highlanders, the Royal Army Ordinance Corps, and two motorcycle companies of a French division légère motorisée, flotsam and jetsam from the battle raging only a few miles to the south of them. Some indication of the value of French troops, as opposed to their senior officers, is given in the account of Brigadier Guy H. Gough, DSO, MC, then the officer commanding the battalion:

Later during [the] day survivors of French tanks and motorized units . . . trickled in in small numbers. Despite the fact that they had very few officers among them . . . [they] proved to be of a fine type, hardy, stouthearted to a degree and full of undampable cheerfulness. Their spirit of comradeship in moving to the hottest spots to help us, and in sharing with us anything from their weapons to their wine was worth going a very long way to meet. They were undaunted by the heavy casualties they suffered . . . and their zest and delight in shooting Germans was most entertaining.

These were not regulars like the fusiliers; they were French reservists, who often gave their position away by opening fire at too great a distance, and “suffered from a reckless disregard for concealment,” two of the worst sins for a professional soldier, but it is interesting to note that when circumstances put French and British troops together they fought equally well, and were not discouraged by heavy casualties or the inability to speak each other’s language.

This mixed batch of soldiers held their position for four days and nights of hard, continuous fighting against a much larger number of better-equipped Germans, despite unopposed German dive-bombing by day, heavy shelling by night, and constant German attempts to cross the canal. Only a handful lived to undertake the retreat to Dunkirk, but it was the stubborn resistance of men like these that not only preserved the BEF but was beginning to take its toll on the enemy.

The dogged defense of Arras (which Rommel had mistaken for a full-scale attack), the mounting German losses in men and tanks, and now the fierce, disciplined resistance of regular infantry, was finally beginning to alarm the OKH as news of it trickled in. Colonel Schmundt, Wehrmacht adjutant to the Führer, called insistently for news. The fact that Amiens and Abbeville were in German hands, or that Kleist’s armored divisions were threatening Boulogne and Calais—all of these victories were beginning to be obscured by doubt and caution.

The painfully small number of British and French soldiers holding the line along the Lys River, like the 2nd Royal Irish Fusiliers, though they could not have known it and might not have cared, were about to make history.

Hitler arrives at the front.

_________________________

* Executed by Napoleon for treason, the duke remains famous for inspiring the immortal bon mot of Talleyrand when asked whether the execution was not a crime: “C’est pire qu’un crime, c’est une faute.” (It’s worse than a crime, it’s a mistake.)

† This may have been an error on Churchill’s part. Since the BEF was facing south and east, the Belgian Cavalry Corps would have been on its left, not its right. On the right of the BEF was Guderian’s panzer corps, approaching the Channel ports.

‡ He was up at the same time as W. H. Auden, Evelyn Waugh, and the aesthete Harold Acton (parodied as “Anthony Blanche” in Waugh’s Brideshead Revisited), but there is no evidence that he knew them, although he calmly read Waugh’s Decline and Fall while under shelling and bombardment at Dunkirk.

§ In England, of course, “public schools” are actually private boarding schools, and a basic class divider.

¶ The 2nd Royal Norfolk Regiment indicates the Second Battalion of the Royal Norfolk Regiment. When two numbers appear, e.g., 1st/5th Queen’s, it means that the surviving elements of the First and Fifth Battalions, the Queen’s Regiment, have been merged into one battalion for the time being.