General Heinz Guderian.

General Heinz Guderian.

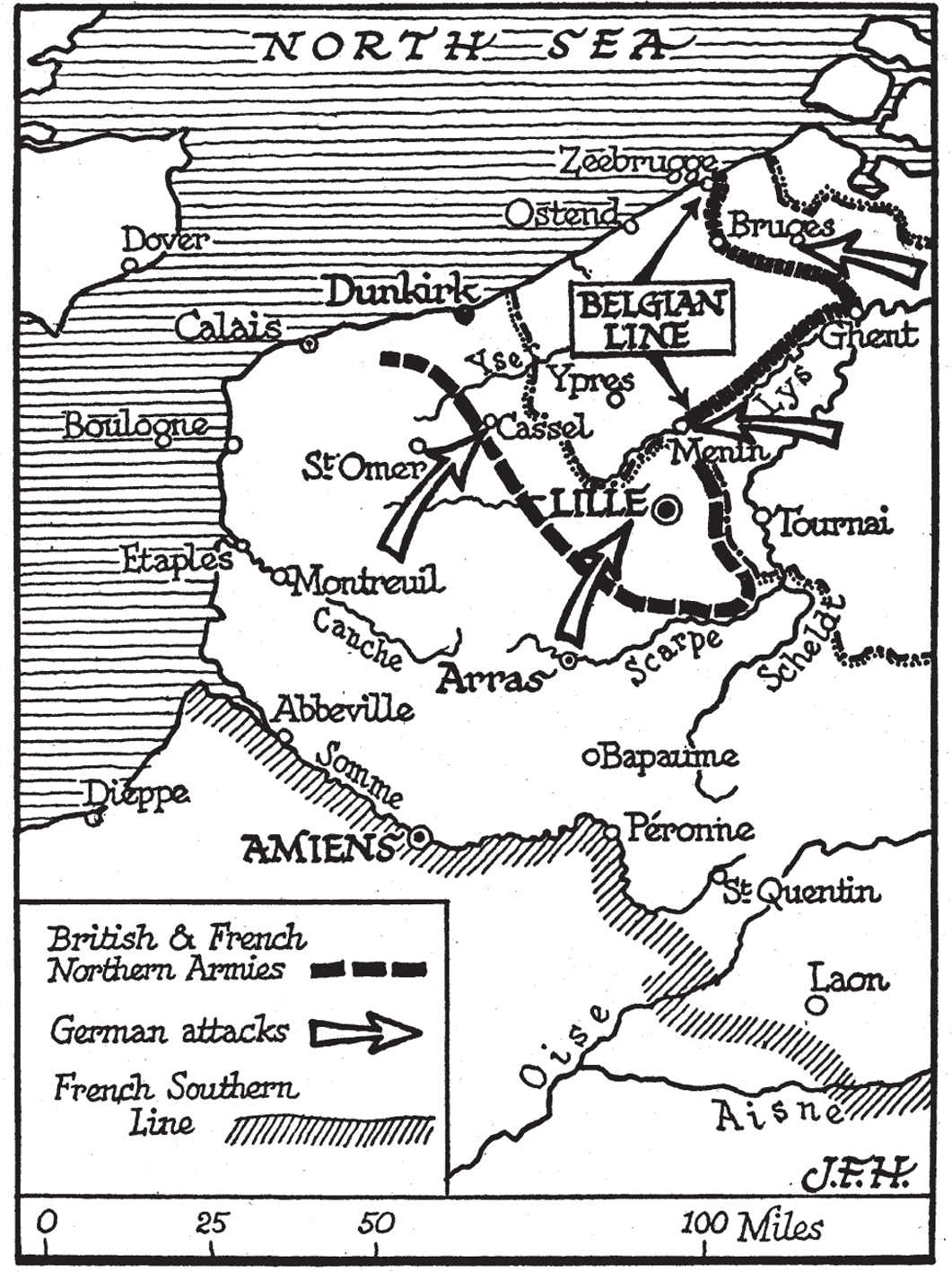

IN LONDON A faint note of alarm had crept into the newspapers. The Rt. Hon. Alfred Duff Cooper, DSO, MP,* Churchill’s pick as minister of information, did his best to put a cheery and optimistic face on things, egged on by Brendan Bracken, the prime minister’s parliamentary private secretary, but even the crudest newspaper map showed a threatening picture as German forces threatened Boulogne and besieged Calais. Although General Weygand got a very good press as the new commander in chief of Allied forces, and was reported—quite incorrectly—to be fighting at the head of the French Army (“WEYGAND TAKES COMMAND ON BATTLEFIELD,” hailed the Daily Mail), there was still no sign of the promised major French attack from the Somme toward the encircled BEF, the French First Army, and the Belgian Army. “British Take Up New Line,” the Times reported with its usual stoic calm, while Nanny Low’s Daily Mail reported enemy armored columns destroyed or cut off under the enormous banner headline “GERMANS THROWN BACK.” Still, all but the most credulous of readers could hardly help noticing the dissonance between reports from the war correspondents in the field and the blaring headlines on the front page of the more popular newspapers. The inside stories were notably more cautious, except for those from the Air Ministry, which were universally triumphant: hundreds of German aircraft shot down and German headquarters and supply dumps bombed to smithereens, as if the RAF were fighting a separate war—which the frontline troops believed was the case anyway, since they seldom saw any British fighters, and were attacked without letup by German Stukas.

Duff Cooper, as minister of information.

My father greeted the morning and afternoon newspapers with his usual weary sigh. Korda family affection for Brendan Bracken and Duff Cooper did not prevent him, as a Central European, from recognizing propaganda when he saw it. Nanny Low must have sensed that things were going badly too, for she made me add the British Expeditionary Force to my prayers, and chose this moment to give me a small, leather-bound Collins Bible, a miniature “pocket” version of her own, about the size of a deck of cards with type so tiny that I can hardly read it now even with the aid of a strong magnifying glass. It was an expensive present, with gilt edges and woven gold braid end bands, printed on almost translucently thin paper, and shows few signs of wear to the black Morocco binding after accompanying me for seventy-five years. She signed the flyleaf and dated it: 1940.

Although I did not know it at the time, an almost equally impressive piece of printing was downstairs on my father’s cluttered desk, a British passport, in those days a substantial, stiff document bound in gold-stamped imitation blue leather, proclaiming me a “British Subject by Birth.” My previous travels, such as they were, had been as an addition to my mother’s passport.

Now, without anyone’s telling me, I had my own.

The bond between England and “the Channel ports” of France goes back to the twelfth century. All of them have been in English hands for long periods of history, and sometimes treated as English possessions. When Henry VIII’s eldest daughter, Queen Mary (also known as Bloody Mary for her persecution of Protestants), was told that Calais had at last been taken by the French, she said, “When I am dead and opened, you will find ‘Calais’ written on my heart.”

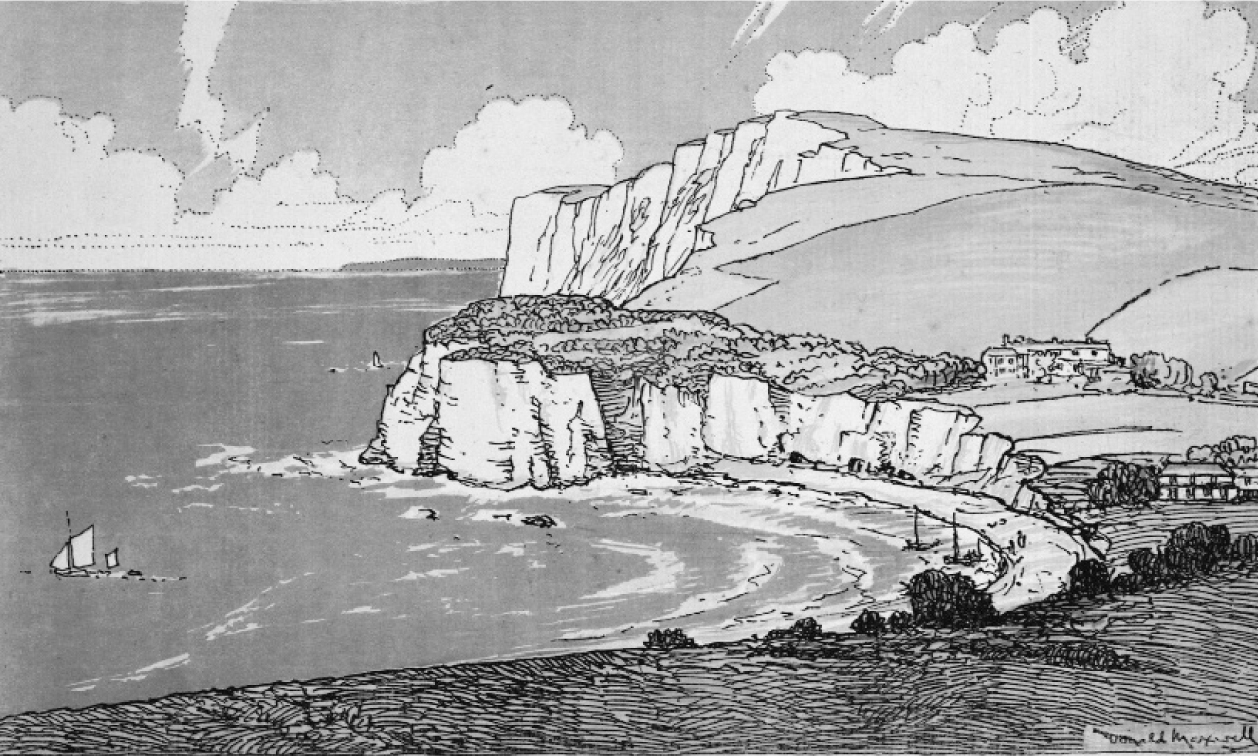

Until the postwar advent of cheap air travel, the British mostly entered France through the Channel ports of Boulogne, Calais, and Dunkirk. By the late nineteenth century all these ports had signs in English, English-style pubs for “day trippers,” they were, at least in spirit, partly English, as well as a haven for those fleeing from England in debt or disgrace, like Nelson’s beloved Lady Hamilton, who died in Calais, or Oscar Wilde after his release from prison. The Strait of Dover is less than twenty-one miles wide at its narrowest point—from Boulogne Napoleon had gazed longingly at the White Cliffs of Dover through his pocket telescope, from Dover Byron had “cast the dust of England from his feet.”

The White Cliffs of Dover.

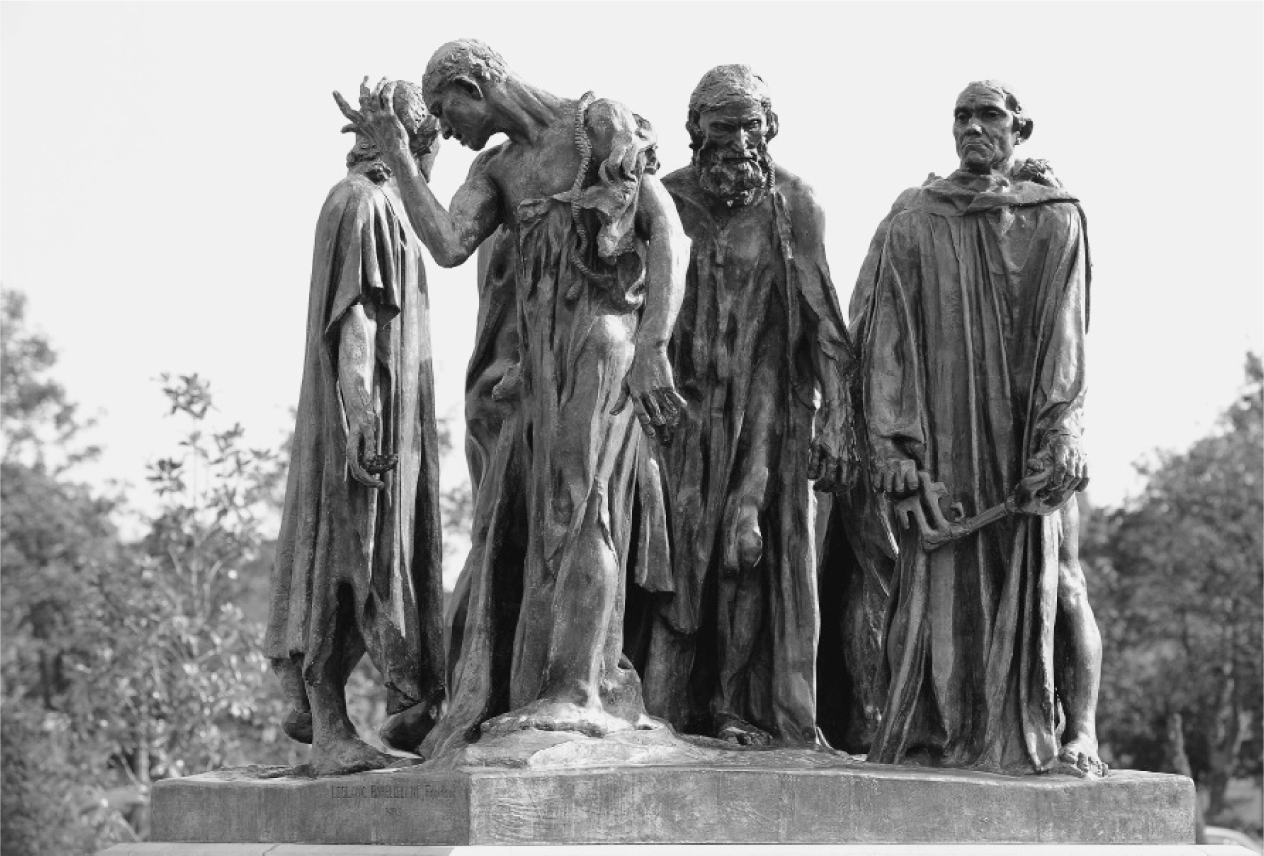

This proprietorial feeling toward the Channel ports was reinforced by centuries of trade and shared, if unhappy, history—perhaps Rodin’s most ambitious sculpture is his portrayal in bronze of The Burghers of Calais, commemorating King Edward III’s demand in 1347 that its six richest citizens surrender themselves barefoot, each with a noose around his neck to be hanged in return for his sparing their city.† The desire to hold on to the Channel ports was instinctive, as well as strategic. So long as they were held, it was possible, at least in theory, to reinforce and supply the BEF and, if worse came to worst, to attempt to evacuate it. If they were lost, then the BEF was trapped.

The Burghers of Calais by Auguste Rodin.

None of these ports was ideal. Compared with Le Havre, Cherbourg, or Brest they were small, could only take a limited number of ships at a time, and even then not the larger ones, but by May 21, 1940, the bigger ports, with their huge depots of British weapons and supplies, were out of reach for the BEF, besides which the Channel ports seemed to many Britons like their only connection with the Continent, hence the famous joke about a headline in a British newspaper that read, “HEAVY FOG IN CHANNEL—CONTINENT CUT OFF.”

By the twentieth century the French Channel ports were no longer the important commercial asset they had once been, but much British trade still moved as yet unmolested through the Strait of Dover. A good part of London’s coal supply, needed for heating, electricity, and gas throughout the great city, still came by ship from Bristol through the narrow strait and up the Thames. It remained to be seen whether Britannia still “ruled the waves” in the global sense, but in the national mind the Strait of Dover was England. The country was still that “precious stone set in the silver sea / Which serves it in the office of a wall / Or as a moat defensive to a house / Against the envy of less happier lands.” John of Gaunt’s famous words of warning in Shakespeare’s Richard II were quoted often in 1940, the Channel having lost none of its mystic and strategic importance since the old man’s time. It was still England’s “moat,” and nobody mistook which “less happier” land was threatening it now.

Queen Elizabeth I, Henry VIII’s second daughter, rode down to Tilbury in 1588, as bonfires were being lit from the Lizard to London to signal that the dreaded Spanish Armada had at last been sighted sailing for the Channel, to review her gathered army and proclaim one of the most defiant speeches in English history: “I know I have the body of a weak and feeble woman, but I have the heart and stomach of a king, and of a king of England too, and think foul scorn that Parma or Spain or any prince of Europe should dare to invade the borders of my realm.” Feelings on the subject had not cooled down since that time, even though General Weygand dismissed the Channel rather snidely, though not inaccurately as “a pretty good anti-tank ditch.”

It would have been unnatural for a government led by Winston Churchill not to fight for the Channel ports. He and Queens Mary and Elizabeth I would have been in agreement on that point despite the four centuries that separated them. Strategically, it might have made sense to concentrate what forces there were on one of them, probably Dunkirk because it was the closest to the BEF, but there was never any doubt that Churchill would prefer to fight for all of them. As early as May 21 the 2nd Welsh Guards and the 2nd Irish Guards, both part of the 20th Guards Brigade, were shipped overnight to Boulogne from Dover on two small passenger steamers, SS Biarritz and SS Mona’s Queen, escorted by three destroyers. The 2nd Welsh Guards were still in training, in fact was in the middle of a training exercise in the pine forest near the staff college at Camberley when it received orders to “embus” for Dover. Twenty-four hours later the battalion was “fighting for their lives—and for the lives of many more”—in Boulogne, and thirty-six hours after their arrival in France those who had survived were home again.

German tanks were already close to Boulogne when they arrived, and the quay was packed with British, French, and Belgian soldiers, civilians and even German prisoners of war all waiting or hoping to be evacuated. One Welsh Guards officer noted, “In the midst of this very orderly crowd stood three or four men with led horses—the chargers of HRH the Duke of Gloucester‡ and the commander in chief, Lord Gort. I was sorry for the groom: he was obviously very tired and puzzled as to how he was ever going to get his chargers on a boat. Later I was told they were shot on the quayside.”

This slightly grim note is altogether appropriate. The brigade’s orders were to defend Boulogne “to the last man and the last round,” but there was no way two battalions of infantry, even from the Brigade of Guards, could hold a whole city, in addition to which they rapidly learned that infantry, however well trained, could not defeat a determined attack by a large armored force. A British regiment of cruiser tanks and another battalion of infantry that were supposed to arrive from Calais to support the defense of Boulogne never turned up—they were already under siege in Calais—which made a prolonged defense even more problematic. A French infantry division was supposed to be blocking the German advance to the south of Boulogne, but there seems to have been very little communication between General Lanquetot, the French commander, and Brigadier W. A. F. L. Fox-Pitt, commanding the 20th Guards Brigade.

The 2nd Welsh Guards were expected to hold almost seven miles of a “defensive perimeter” northwest of the city of Boulogne, through which all the major roads to the city passed. Even with the help of a mixed bag of French infantrymen, Royal Engineers, and Auxiliary Military Pioneers (pick-and-shovel soldiers, not trained infantrymen), this was an impossible task. The 2nd Welsh dug themselves in as best they could forward on high ground, but the Liane River separated them from the 2nd Irish Guards, so there was no way for the two battalions to mount a coordinated defense.

Boulogne is a cramped and narrow port, overstuffed with history. Its substantial walls were built in medieval times to protect it from the English, and it contains the tallest column in France to mark the place where Napoleon distributed eagles to the 200,000-man “Army of England,” which was camped in the hills around here in 1803 and 1804 waiting to embark in wooden barges for the invasion of England that never took place. The ground rises sharply beyond the harbor and the roads to the “old walled town—known as the Haute Ville or ‘the Citadel’—are steep.” General Lanquetot took over the Citadel for his headquarters, to organize the defense of the city, apparently unaware that the Irish and the Welsh Guards were attempting to hold the high ground around it, or that his own division had been so badly shot up and scattered by German tanks and dive-bombers on its way to Boulogne that most of it would never arrive.

There were thus two separate battles at Boulogne, one by a small part of General Lanquetot’s division at the Citadel, most of them the clerks, typists, and drivers of his headquarters, the other a failed British attempt to hold the high ground (2nd Welsh Guards) to the northwest and the area between the river and the sea (2nd Irish Guards) against the German 2nd Panzer Division (with the German 1st Armored Division in support). Because of the evacuation of the Rear General Headquarters of the BEF, part of a general plan to “get rid of useless mouths” from the Channel ports as soon as possible, Fox-Pitt had no radio communication with the UK, and no means to communicate with his two battalions or with General Lanquetot except by dispatch riders.

Not surprisingly the thinly spread British were constantly outflanked by German tanks, and as the Germans began to bring artillery and dive-bomber attacks to bear on them, they were obliged to undertake a fighting retreat with heavy losses step by step back into the city. By the evening of May 23 German tanks, infantry, and snipers had broken through into the city itself, and much of Boulogne had been destroyed. Although the harbor itself was now under fire from German artillery, mortars, and machine guns, the Royal Navy continued to send destroyers in to engage targets on shore and embark nonfighting troops. A French destroyer was sunk, and the captains of two British destroyers were each killed on their own bridge, though not before one of them, the captain of HMS Keith, had managed to pass the message to Brigadier Fox-Pitt that he was to embark what remained of his brigade rather than fight to the last man. Owing to the large number of wounded and “unattached men” it was some time before the fighting troops, who were now holding “a close perimeter” around the docks, could begin to board. Even so, 453 of them were left behind to become prisoners of war, which together with the dead and wounded counted for more than half the brigade’s strength.

Perhaps almost as unfortunate was the fact that it had not been possible to inform General Lanquetot in the Citadel of the brigade’s departure, so he woke up in the morning to find the British gone. The general and his headquarters staff fought on for another twenty-four hours before surrendering. This was yet another source of friction (and embarrassment) between the Allies, coming as it did on top of an angry claim by General Weygand that Lord Gort had abandoned Arras “without warning and without orders,” which was passed on directly from M. Reynaud to Churchill, and which produced a brief, but distracting, flare-up until it became clear that since the French had not shown any sign of keeping their part of the bargain—an advance from the Somme to meet the Armies of the North halfway—Lord Gort had had no option but to give up Arras and make for the coast.

Edward Spears MP, whom the prime minister had selected to be his “personal representative” to M. Reynaud—once again Spears had been launched into the highest level of politics by his uncanny command of spoken French—was quickly flown to Paris in an RAF bomber to pour oil on these particular troubled waters, this time hastily promoted to the rank of major-general (he was only just able to get his new badges of rank sewn on his old World War One uniform, and even then left without time to acquire a general’s cap), and the crisis passed with nothing worse than increased ill will and suspicion toward the British on the part of General Weygand.

That is not to deny that the capture of Boulogne was without serious consequences. The 2nd Welsh Guards and the 2nd Irish Guards had been ordered to hold Boulogne to the last round and the last man, and that order was then withdrawn. When it came to Calais, Churchill gave the same order to the troops holding it, at least in part to impress upon the French that the British meant business, and this time the troops would not be withdrawn.

Although the capture of Boulogne represented the triumph of the plan that General von Manstein had drawn up and that General Guderian had carried out so brilliantly, it produced no rejoicing on the German side. The panzer divisions had crossed the Ardennes unseen, then crossed the Meuse River and driven straight west to the Channel, all just as Manstein had promised, scything the French Army in two, isolating the BEF, and creating an anvil against which the hammer of Army Group B could crush the Belgian Army, all of it accomplished in less than two weeks, and with fairly minimal German losses. But Guderian was smarting over the fact that one of his panzer divisions had been held back by five hours by Kleist. Guderian had used 2nd Panzer and 1st Panzer to take Boulogne and isolate Calais, but the British resistance at both places was stronger than he had expected—the 20th Guards Brigade had apparently not fought in vain—and in any case it was Dunkirk that Guderian wanted. He believed he would have already have reached it had Kleist not interfered with him.

At a higher level, there was a strange combination of doubt and caution at the apparent success of the Kleist Panzer Group. To General Halder’s fury, the Führer was still worried about the French Army to the south, no doubt because the bulk of the German infantry was still coming up slowly behind the armored “spearhead,” inviting a counterattack. Halder’s diary is studded with exclamation marks and snippy comments in parentheses about Hitler’s concerns: (“Pater noster!”) (“That is the fault of interference at the top!”), as well as a brief comment about “the rather tense atmosphere” around Hitler, who did not share Halder’s nerveless confidence in the staff work of the German Army. Hitler was displaying all the signs of a nervous crisis as he decided on his next move. A clue to his inner thoughts, however, may be found in Halder’s diary entry for May 21: “Enemy No. 1 for us is France. We are seeking to arrive at an understanding with Britain on the basis of a division of the world.”

This is not the kind of grandiose geopolitical thought that would have occurred to the orderly, practical military mind of General Halder, so he was clearly reporting a remark of Hitler’s, without endorsing it. Evidently, the idea of “a regime change,” as it would now be called, in which “the right people” in London would form a sensible government to replace Churchill and his cronies and make peace with Germany once France was defeated still lurked in Hitler’s mind, doubtless reinforced by Göring and Ribbentrop whenever they could pry the Führer away from the map table.

It was clear enough to everyone that the next step—Fall Rot, or Case Red, as it was called—was to cross the Somme, cut off the French forces in and behind the Maginot Line and achieve a final victory over the French Army, and for this to be undertaken successfully the panzer divisions would have to play their part. One factor was the need to disentangle Army Group B from where it was, in Belgium and Holland, a huge task, but not a significant problem for the superbly trained staff officers of the OKH. The other was the question of whether the German tank crews, having fought their way from Sedan to the Channel, needed a rest, and of course the extent to which their losses could be replaced and their tanks serviced and repaired. Much like horses in the old days when a period of rest and shoeing was necessary after a long cavalry advance, the tanks were thought to need servicing. As everybody knows, cavalry troopers can be pushed much harder than their mounts; in the history of warfare it has always been so. Given the right leadership, men can handle starvation rations, lack of drinking water, lack of rest, but horses break down or die in similar conditions, nor can they be moved forward by patriotic speeches or martial music.

Guderian’s notorious impatience and quick temper, as well as his idée fixe about the role of tanks, worked against him in this case. The harder he argued, the less anybody listened. He could have pointed out—after all, nobody knew better—that this had been carefully thought out. The tank crews were trained to service their tank at the end of each day before they fed themselves or rested, and every care had been taken to provide each panzer division with mobile service units that could repair the tanks, and if necessary replace the all-important tank tracks, but the comparison between horses and tanks was firmly, if unconsciously, imprinted at a much higher level than his. This caution was apparently passed on to General von Rundstedt, and imprinted itself on that otherwise superbly objective and professional military mind. He needed Kleist’s armor for Case Red, and he did not want any of it wasted or damaged merely so Guderian could prove he could take all the Channel ports, besides which the lesson that Rundstedt had taken from the British fight at Arras, and now at Boulogne, was that British powers of resistance were more formidable than those of the French Army.

Rundstedt’s mind was already fixed on the defeat of France, he did not want that to be jeopardized by dealing with the BEF, which was in any case retreating toward Dunkirk, taking it effectively off the field. His views were passed on to Hitler, where they added to the level of stress on and around the Führer.

_________________________

* Married to Lady Diana Cooper, a famous beauty, Duff Cooper became a very successful ambassador to France and was raised to the peerage as Lord Norwich. He was a hugely successful seducer of women, and his diaries, edited by his son, are fascinating and full of scandal. His biography of Talleyrand is a classic.

† The six men were pardoned at the urging of the queen.

‡ Major-General HRH Prince Henry, Duke of Gloucester, was a younger brother of King George VI, and at the time chief liaison officer of the BEF to the GQG. He had had a much hushed-up, but scandalous, affair, begun when he was on safari in Kenya, with Beryl Markham, the glamorous aviatrix (a major character as an adolescent in Isak Dinesen’s Out of Africa, and author of West with the Night, a book much admired by Ernest Hemingway).