Hitler at the map table; on the right, a visibly skeptical General Halder.

“Fight It Out to the Bitter End”

Hitler at the map table; on the right, a visibly skeptical General Halder.

THE ATTEMPT TO defend Boulogne was a sad failure. The attempt to defend Calais was a tragedy. Although shipping was still coming into Calais—including 350,000 rations for the BEF—the German 1st Panzer Division was already closing in on the town and seizing the main roads around it.

Late in the evening of May 23 the prime minister saw the king to warn him that if the attack promised by General Weygand “did not come off, he would have to order the BEF back to England,” as the king confided to his diary. The king was stoic, but horrified: “The very thought of having to order this movement is appalling, as the loss of life will probably be immense.”

Confusion haunted the reinforcement of Calais. The 30th Motor Brigade was ordered “to proceed to the relief of Boulogne” as rapidly as possible, then was diverted at the last minute to Calais when Boulogne fell. The brigade, under the command of Brigadier C. N. Nicholson, consisted of the 1st Prince Consort’s Own Rifle Brigade, 2nd King’s Royal Rifle Corps, 7th Queen Victoria’s Rifles, plus the 3rd Royal Tank Regiment and a Royal Artillery antitank battery. This sounds like a more formidable force than it really was. The QVR was a motorcycle battalion that had been shipped without its machines, and many of its men were armed only with a revolver. Artillery, heavy machine guns, mortars, ammunition, and many other items had been so badly loaded that much of it remained unreachable below deck. The electricity supply to the docks of Calais had been interrupted and the French dockers were on strike, so it was only possible to unload the tanks of the 3rd RTR one by one using the ship’s own derricks, a slow job that could not even begin until the deck had been cleared of thousands of gallons of gasoline in leaky tin cans. Complicating this process was the fact that each tank’s gun had been removed and heavily greased, so time had to be spent stripping off the heavy preservative grease and “remounting” the gun. The captain of the 3rd RTR’s ship tried to sail before unloading was completed and stayed only because he “was held at gunpoint” by a 3rd RTR officer.

Contradictory orders plagued the Calais garrison—such light tanks and infantry as were ready were ordered first to proceed west to relieve Boulogne, but when it fell they were redirected east to escort a convoy full of rations to Dunkirk, only to find that the Germans had already blocked the road. By May 23 the British had been driven back to the walls of Calais, which having been built in the seventeenth century were now more of a historical curiosity than useful, and were effectively under siege by two armored divisions, with the bulk of 3rd RTR’s tanks disabled or destroyed. By May 24 the Germans had artillery on the high ground surrounding Calais and the city was under constant shelling. Losses began to mount rapidly.

In the normal course of things the right decision would have been to evacuate the troops as soon possible, but Calais was not a normal town. In the first place, it was, more than any other French Channel port, deeply embedded in English history, and in the second, abandoning it would mean that two German panzer divisions would be free to invest Dunkirk, the last port remaining from which the BEF might be evacuated. A proposal from the navy to begin the evacuation of Calais was rejected on May 24 with a stiff note from the prime minister to General Hastings Ismay, his military adviser: “This is surely madness. The only effect of evacuating Calais would be to transfer the forces now blocking it to Dunkirk.” This was followed by a longer and angrier note on the situation, again to Ismay. “I cannot understand the situation around Calais. The Germans are blocking all exits, and our regiment of Tanks is boxed up in the town because it cannot face the field guns planted on the outskirts. Yet I expect that the forces achieving this are very modest. Why, then, are they not attacked? . . . Surely Gort can spare a Brigade or two to clear his communications and to secure the supplies vital to his Army.”

It was rare for Churchill to criticize Lord Gort, who was now in the difficult position of trying to move a quarter of a million men back toward the coast, and who in any case had no armored formation to spare for Calais. By the midafternoon Churchill had calmed down enough to listen to a fairly dispassionate statement on the situation at Calais to the War Cabinet from General Ironside. “German tanks had penetrated past the forts on the west side of Calais and had got between the town and the sea. The Brigadier . . . thought that it would be useless to dribble more infantry reinforcements into Calais.”

The prime minister was under constant pressure from M. Reynaud to explain why Lord Gort had given up Arras, so he was loath to give up Calais as well. There was still no sign of the promised French attack to the northeast from the Somme, and in the meantime momentous great events were going on. The King of the Belgians was threatening to surrender, which would lay Lord Gort’s left flank open to attack, General Weygand was already warning that he might have to give up Paris, and M. Reynaud was suggesting an approach to Mussolini, to seek out Hitler’s terms for a negotiated peace. In the circumstances, Churchill did not feel that Calais could be given up as Boulogne had been.

By the night of May 26 he had made up his mind, as Ismay reported: “A telegram was sent to the commander at Calais, Brigadier Nicholson, telling him that his force would not be withdrawn, and that he must fight it out to the bitter end. . . . The decision affected us all very deeply, especially perhaps Churchill. He was unusually silent during dinner that evening, and he ate and drank with evident distaste. As we rose from the table, he said, ‘I feel physically sick.’ He has quoted these words in his memoirs, but he does not mention how sad he looked as he uttered them.”

Churchill sent General Ironside, who was about to be replaced as CIGS by General Dill, a draft of the order he wanted sent to Brigadier Nicholson, as opposed to the previous rather lukewarm one, which made him ask whether there was “a streak of defeatist opinion in the General Staff.” “Defence of Calais to the utmost is of the highest importance to our country and our Army now. . . . The eyes of the Empire are upon the defence of Calais, and His Majesty’s Government are confident you and your gallant Regiment will perform an exploit worthy of the British name.” In the end Churchill retired alone to send his own message to Brigadier Nicholson, emphasizing the most important point: “Evacuation will not (repeat not) take place, and craft required for above purpose are to return to Dover. . . .”

Calais was already in ruins from nonstop German artillery bombardment and from bombing; much of the city was on fire and darkened by smoke. The British had withdrawn to the area of the Citadel and the Old Town to shorten their line. The men were short of everything, not only food and ammunition, but even water since the water mains had burst, yet they fought on. The Germans were impressed and surprised—having reached Calais so quickly, they had not expected to have to fight this hard for it. It was also a demonstration, although too late, of what might have been accomplished had the French and the British fought together under a vigorous commander. In the words of the official British history, “The King’s Royal Rifle Corps, and other detachments of the Queen Victoria’s Rifles in the old town, fought grimly to hold the three main bridges into the town from the south. . . . A mixed British and French force held a key bastion and the French garrison in the Citadel fought off all attacks upon it though sustaining heavy casualties. Brigadier Nicholson established there a joint headquarters with the French commander.”

Nicholson had already been offered one opportunity to surrender, when the Germans presented the mayor of Calais under a white flag with a German escort. Nicholson turned the offer down politely, remarking that if the Germans wanted Calais “they would have to fight for it.” During the afternoon of May 25 “a flag of truce was brought in by a German officer, accompanied by a captured French captain and a Belgian soldier.” Nicholson turned down this second demand for surrender, with great dignity and strict regard for military correctness:

“The answer is no as it is the British Army’s duty to fight as well as it is the German’s.

“The French captain and the Belgian soldier having not been blindfolded cannot be sent back. The Allied commander gives his word that they will be put under guard and will not be allowed to fight against the Germans.”*

One senses a certain regret on the part of the Germans at Nicholson’s refusal to surrender, but early the next morning heavy bombing further shattered the Old Town and separated the remaining British troops into small, isolated parties fighting separately amid the rubble. In the afternoon of May 26 the Germans finally managed to break into the Citadel and capture Brigadier Nicholson, and by evening the “fighting ceased and the noise of battle died away as darkness shrouded the scene of devastation and death.”

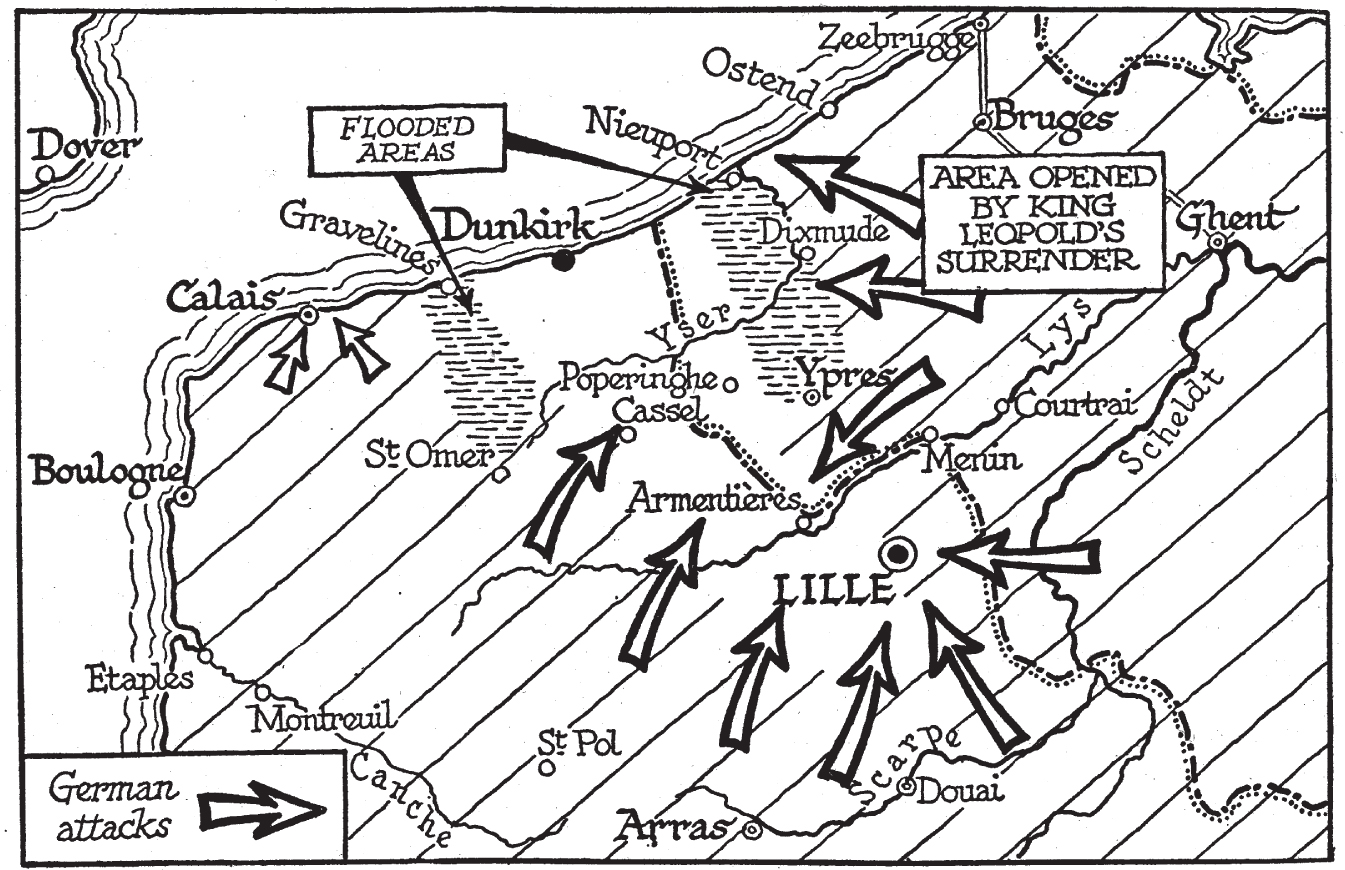

Although the defense of Calais was later dismissed by General Guderian as heroic, but making no difference to the course of events, in fact the sacrifice of the 30th Brigade at Calais added to the hesitation and confusion of the German high command. The distance from Calais to Dunkirk is less than thirty miles, and once Calais had been taken there was no apparent reason why the two German armored divisions should not have continued on to take Dunkirk, which at this point had very little in the way of a defense. General Reinhardt’s XXXXI Panzer Corps was even closer than the spearhead of Guderian’s XIX Panzer Corps—less than twenty miles south of Dunkirk. Logically, the Germans could have—and should have—taken Dunkirk by May 27 or 28, and cut the BEF from any possibility of evacuation. As is so often the case, a historic victory was to be followed by a historic blunder.

“Victory has a hundred fathers, defeat is an orphan.”† The blame for the BEF’s escape from Dunkirk has been shifted from one person to another over the past seventy-five years, and not surprisingly most of the surviving German generals attributed it to Hitler, who was in no position after May 1945 to contradict them. In fact, Hitler was reacting to the caution of his most senior generals—all except the dour and clear-sighted Halder, whom he disliked—rather than imposing his will on them. The dizzying success of Case Yellow so far had made them nervous, with the exception of Guderian, who as a mere corps commander had no influence on higher strategy, and whose passionate belief in the efficacy of armored warfare as he envisioned it struck many of his seniors as monomaniacal. The panzer divisions were not the answer to every problem, they felt, and the fact that Manstein and Guderian had been right about massing them in the Ardennes did nothing to endear them to older and wiser heads.

The impulse to halt the panzer divisions was not new. It had come up for the first time shortly after they had crossed the Meuse, as the German generals (and their Führer) looked toward the west with concern, searching for the first signs of the expected counterattack from the French Army that would separate the panzer divisions from the infantry coming up behind them more slowly, a replay of the Battle of the Marne that had stopped the Germans in September 1914 at the beginning of the First World War. It did not occur to them that France had no equivalent in 1940 of General Joseph Joffre, nor did it occur to either General Gamelin or his successor General Weygand to replay his part. Another Joffre, a man of indomitable will, might have gathered all the divisions waiting behind the Maginot Line and boldly flung them against the Germans at the crucial point, but no such man existed. There would be no repetition of the heroic legend of “les taxis de la Marne,” when the Paris taxicabs carried troops straight from the railway stations as they arrived to the front line. Neither psychologically nor militarily was the French Army in 1940 prepared to stage the massive attack on the exposed German left flank that the Germans feared.

The second halt in the advance of the armored divisions seems to have been caused by the unexpectedly stiff resistance of the British at Arras, which was briefly misread as a full-scale British counterattack. In both these cases Hitler was merely responding to Rundstedt’s interpretation of the situation—Rundstedt, though the most implacable and levelheaded of Hitler’s senior generals, still anticipated a French attack of thirty or forty divisions. He had known Gamelin before the war, and respected him; the idea that Gamelin was paralyzed and unable to act once the folly of his advance into Belgium was clear to him did not cross Rundstedt’s mind.

The pause ordered after the Germans took Arras infuriated General Guderian, but did not seem unreasonable to the panzer troops themselves. General Rommel, commander of the 7th Panzer Division, wrote to his wife, Lucia, with his usual matter-of-fact professional calm about the violence of war: “A day or two without action has done a lot of good. The division has lost up to date 27 officers killed and 33 wounded, and 1,500 men dead and wounded. That’s about 12 percent casualties. . . . Food, drink and sleep are all back to routine. Schraepler [his aide] is back already. His successor was killed a yard away from me.”

The next rush forward took Guderian’s panzer corps to Calais, and Reinhardt’s to within easy reach of Dunkirk, only for them both to be halted again on May 24 by a surprising order that the panzer divisions were to stop along the line of “the Aire-St. Omer Canal,” just short of Dunkirk. Various reasons have been given for this disastrous decision, which allowed the BEF to reach Dunkirk and begin evacuation, but as usual with Nazi Germany it seems to have been a mixture of the practical and the theoretical. Some historians believe that Hitler was concerned that Flanders, with its many canals and marshes (with which he was familiar from his service in the previous war), was unsuitable ground for tanks. This may have been so, but it would have been unusual for Hitler to override his generals’ advice on a purely technical matter like this in 1940. (It became more common once he had lost confidence in them in 1942.)

General von Brauchitsch.

General Halder, while complaining as usual about the “unpleasant interview” and “painful wrangles” between the army commander in chief, Colonel General Walter von Brauchitsch, and the Führer on the subject, also notes that Hitler’s intention was to fight the decisive battle in northern France, not in Flanders, for “political” reasons, and that “to camouflage this political move,” the “halt order” for the panzer divisions was to be attributed to the problems of the terrain.

It is hard to see any sensible “political” advantage to this subterfuge, or indeed whom it was supposed to deceive, and Halder puts none forward, which may have been his way of saying that he did not believe a word of it. In any case, “political” did not have the same meaning in Nazi Germany as it did in Britain, France, or the United States, where politics implies an orderly process for reconciling different opinions. In the Third Reich there was no tolerance for different opinions; “politics” merely meant the elaborate political structure for putting Hitler’s wishes into practical effect at every level, and for making the German people identify itself with them, and accept them with enthusiasm.

It is always difficult to penetrate the thought processes of Hitler—he was a past master at deceiving others, but he was also no slouch at deceiving himself—and he was quite able to keep two apparently conflicting motives in his mind at the same time. However, parsing Halder’s notes carefully, it is apparent that Hitler wanted the panzer divisions halted, was tired of arguing about it, and used his ultimate weapon in arguments with his generals, the “political” motive. This was (and would remain) his trump card—the generals were not supposed to have any involvement in or insight into “politics,” an area of expertise that the Führer reserved for himself. They had given all that up for good after the “Night of the Long Knives” in 1934, when every soldier took a personal oath of loyalty to the Führer. They could (and did) argue with Hitler about tactics, the terrain, even to a degree about strategy, but not about “politics,” which in a one-party, one-man dictatorship meant everything that was not directly connected to the battlefield.

Somewhere at the back of his mind Hitler may still have believed that the British, or at least some of their major political figures,‡ would give in and that sparing their army might help to convince them of his good will—certainly several of his generals believed so—but at the same time he was aware that Rundstedt wanted to make sure the panzer divisions were intact and rested before undertaking Case Red, the “decisive battle” that would force the French Army to surrender.

Humanitarian aims never played any role in Hitler’s decisions, and therefore did not prevent him from listening to Göring’s claim that the Luftwaffe could annihilate the BEF on the beaches without the help of the panzer divisions, but how much faith he put in that is open to question, for he had already learned that even the most ambitious and well-planned of air campaigns is dependent on good weather. Given the subsequent bombing and shelling of Dunkirk and its beaches, sparing the BEF does not seem to have been one of Hitler’s considerations, so the likelihood is that his major concern was to spare the panzer divisions for the big battle to come, rather than to fritter them away on the BEF, which was already beginning to evacuate.

Hitler is sometimes criticized for interfering too much in military decisions—though he did not interfere much more than Churchill—and sometimes for being “an armchair general,” remote from his commanders in the field. This too is doubtful. On May 24 he went to Rundstedt’s headquarters precisely to thrash out what the next move involving the panzer divisions should be, and heard Rundstedt out with a certain degree of patience. Although Rundstedt denied it after the war, there seems to be no doubt that at the time he urged caution on Hitler. For three fateful days the panzer divisions were halted, even though some of the tanks were so close to Dunkirk that Colonel Wilhelm Ritter von Thoma could see the beach. Whatever the mix of military and political considerations that was in Hitler’s mind on May 24, the decision to halt the panzer divisions was—although it may not have seemed so at the time—a major turning point in the war, and a fatal one for Germany.

_________________________

* This account is in English in the war diary of the German 10th Panzer Division, as quoted in Ellis, The War in France and Flanders, p. 167.

† Usually attributed to President John F. Kennedy, sometimes to Mussolini’s son-in-law the Italian foreign minister Count Galeazzo Ciano, of all people, but it probably goes back to Roman times, if not earlier.

‡ These, we now know, included HRH the Duke of Windsor, Lord Halifax, and David Lloyd George. It cannot have been unknown to Hitler that Lord Halifax, the British foreign secretary, had already discussed with the Italian ambassador in London the notion of asking Mussolini to seek out what Hitler’s peace terms might be.