Vincent, Alexander, and Zoltan Korda.

Vincent, Alexander, and Zoltan Korda.

THE BRITISH PUBLIC was still at the time largely unaware of the scale of the catastrophe in France. For one thing, the French, however bloody-minded they might seem to many Britons, still benefited from their martial reputation in the First World War. The notion that they might be badly commanded, poorly led, and unwilling to fight had not as yet imprinted itself on the mind of the British public, still less on that of the prime minister. For assiduous readers of the Times it was clear enough that something had gone wrong, but only five days after the appearance of the ominous Admiralty announcement that all small ships and motorboats were to be registered, the Times still told its readers that “this great German offensive contains the seed of its own defeat,” and found consolation in the appointment of General Weygand to lead the Allied armies, reminding readers that he had been Marshal Foch’s chief of staff. After all, similar crises had taken place in the previous war, in 1914 when General Joffre stopped the German advance at the Marne, in 1916 when General Pétain held the Germans back at Verdun at the cost of more than half a million French casualties, and in 1918 when General Foch brought to a halt the Kaiserschlacht, the German Army’s last great offensive, which nearly broke the Allied line at a cost of close to 850,000 British and French casualties (and nearly 700,000 German). “I will fight in front of Paris, I will fight in Paris, I will fight behind Paris,” Foch had declared, and since Weygand had been his protégé and devoted follower, surely he would do the same? The powerful French counterattack on the exposed right wing of German Army B as it carried out its armored “scythe” to the sea was eagerly awaited by readers of the Times and also of the more popular newspapers.

In the meantime, had I been more astute (but I was, after all, not yet seven), I might have detected that other things were going on. It was then part of normal routine to be taken to tea at my grandparents’ house in suburban Hendon on Sunday afternoons. My father, for reasons never explained to me, would not set foot in the Musgrove house, and my mother preferred to spend her Sundays in bed resting from her six nights and two matinees a week on the stage, so it was left to my nanny and myself to make this weekly pilgrimage to Hendon. My maternal grandfather, Octavius Musgrove, was a prosperous dentist who always dressed like an Edwardian gentleman, but it was my grandmother Annie who ruled the Musgrove household and exerted her formidable will on her husband, the Irish maid in her starched cap and apron, and the part-time gardener and chauffeur, since neither of my grandparents drove. “Ockie,” as we called him, was from the north of England, and had a strong and undisguised Liverpool accent (recognizable to Americans from the early Beatles hits). My grandmother was also from Liverpool, but had long since refined her accent. She liked to say that her father was “in coal,” but Ockie, when out of her hearing, would say, “Ay, ’e was in coal alright, ’e went from door to door with ’orse and cart shouting, ‘Coal, coal!’ ” Dentistry, primitive as it was in England at the time (my grandfather’s recommendation to all his patients was “’ave ’em all out, dear!” and his favorite tool was the forceps) had raised my grandfather to “professional” status, but he preserved a rich, northern sense of humor, a taste for the music hall, and an appreciation for spirits, wine, and tobacco in all their forms. He wore boldly checked suits, with the result that he looked like a successful bookie rather than a dentist, and a vest (waistcoat) in apricot- or plum-colored velvet, with gold buttons and a gold watch and chain, a gray bowler hat in the summer, and a black one in other seasons.

Hazy though class and regional differences in England were to my father, he had instantly understood how to subvert Ockie, whom he liked, and instituted their regular Saturday luncheon at Prunier on St. James’s Street. They met after my father had attended the morning session of the art auctions at Christie’s or Sotheby’s. “Vincent is not such a bad chap,” my grandfather would say reflectively, and my father felt the same about him. At Prunier they ate well, shared a good bottle of wine, and a glass or two of brandy afterwards. I imagine this luncheon was in part a reliable way my father had invented of irritating my grandmother without seeing her—he always referred to her, though never to Ockie, as “that bloody old voman.”

What the two men found to talk about together over lunch was a mystery to most people, but my father enjoyed silence, and my grandfather Ockie was perhaps happy enough to get away from my grandmother’s chatter and bossiness for a few hours. I accompanied my father a few times, and for the most part they ate in companionable silence. They had both fought, though on different sides, in the First World War, but they never spoke about that, or politics, or marriage in my hearing.

My grandmother represented respectability and tidiness, two incomprehensible concepts to my father, who hated tidiness and lived in a chaos of his own making. He moved everywhere in a cloud of cigarette ashes, scattered scraps of paper with notes or sketches, discarded pencil stubs, and small change. He used a knotted-up polka-dot Sulka necktie to hold up his trousers, and wore his expensive bespoke Lobb shoes unshined, with the laces left untied for greater comfort. The Musgrove house represented everything my father disliked about England, from the crazy paving and the stone gnomes in the garden to the heavy cut-velvet upholstered furniture, the stained glass windows, the smell of furniture polish, and the neat antimacassars. Whenever the subject of the house in Hendon came up, he would say with a heartfelt sigh, “Poor Ockie.”

My grandmother had not approved of my mother’s marrying a Hungarian who at that time spoke little or no English, whose clothes (though admittedly expensive) looked as if he had slept in them, and who had no respect for English middle-class conventions, if indeed he had even noticed them.

A further complication to their relationship was that my grandmother was a classic “stage mother,” who had pushed my mother onto the stage at an early age. This was a result of sibling rivalry between my grandmother Annie and her elder sister Maud Mary, who had not only pushed her daughter Madge Evans into show business as an infant, but all the way to Hollywood and a career as a child star and rival to Shirley Temple. (Madge would grow up to star in Pennies from Heaven with Bing Crosby.) Nothing could be better calculated to alienate my father than having to accept two ambitious stage mothers as relatives by marriage.

In any event, one of Ockie’s neighbors owned a motor yacht, which he kept at Teddington, on the Thames, where it was moored with a lot of other small yachts in what would now be called a marina, but was then just a private boatyard, and he happened to drop in while we were at tea. I had been on the boat several times with my grandparents and knew her. She was painted white with neat blue trim and shiny varnished mahogany, a slow, broad-beamed and sturdy boat, about twenty-five feet long, what might be called “a cabin cruiser” in the United States, but there was nothing in the cabin except a small galley suitable for boiling a kettle, a table between upholstered benches, two bunks, and a pump toilet. The word “yacht” conjures up glamor, but there was nothing glamorous about her, and we only went on short cruises up and down the river, not far from the genteel neighborhoods of Bushy Park and Strawberry Hill, and only in the very calmest of weather, with a wicker tea basket from Fortnum & Mason laid out under the blue-and-white striped awning in the stern. For these occasions Ockie wore white trousers, a striped blazer and a straw boater, and his neighbor sported a jaunty yachting cap as he stood at the helm and we chugged slowly and peacefully among the Thames barges, rowboats, and paddle-wheel steamers. I do not suppose the boat had ever sailed anywhere except the placid Thames upstream from the placid Teddington lock—it would be difficult to imagine her on the open sea, still less as a target for German aircraft, artillery, and torpedo boats.

Dutch schuyt, of which many were used at Dunkirk.

The neighbor happened to mention over tea that he had been surprised to find a chief petty officer of the Royal Navy (roughly the equivalent of an army sergeant-major) holding a clipboard and examining his modest yacht the day before. He had obediently sent her particulars in to the Admiralty after reading the announcement in the Times, but had hardly expected a real live sailor to show up so soon, if at all. In those days everything was being registered and particulars taken down, not just boats, but cars, commercial vehicles, and motorcycles—government departments were intruding everywhere, inspecting cellars, enforcing rationing, requisitioning sporting arms, demanding to see the air raid shelter that was supposed to be built in people’s back garden, stopping people who had left home without their gas mask. It was the age of the bureaucrat and the snooper, so registering his boat with the navy did not seem unusual.

Given the time it would take a postcard to reach the Admiralty from Hendon (those were still the days when the post was delivered overnight in London) that would place the date of the tea at my grandparents on Sunday, May 19—the beginning of the British “counterattack” at Arras and the last day of the French “attempt to stem the flood which broke the Meuse barrage,” and which turned Kleist’s armored group loose to make its advance to the sea. Churchill had been prime minister for only nine days at that date, and had as yet given no thought to evacuating the BEF from the beaches of Dunkirk or anywhere else.

“What’s it all about, then?” Ockie’s neighbor had asked the CPO as they stood on the dock beside his boat.

“No idea, sir,” the CPO replied, with the stony politeness of noncommissioned officers of any service toward civilians.

“I can’t see her as a minesweeper, which is what I hear they’re looking for.”

“Couldn’t say, I’m sure,” the CPO said, carefully writing down the particulars on his form. He gave the boat an appraising look. “She’s got a nice shallow draft on her, though, I’ll say that.” He glanced out at the long row of motor yachts, gleaming mahogany speedboats, and sailboats of every size and shape, all neatly tied up. “A shallow draft is just the ticket,” he said, putting a finger to the peak of his cap, not quite a salute, just a mark of respect, as he went off to look at the next boat.

“A shallow draft,” mused Ockie’s neighbor over his teacup. “Why on earth would they want that?” It was a good question. Boats like his were designed for cruising the river and the innumerable streams that fed into it, many of them quite shallow. A boat designed for the open sea usually has a deeper draft for better stability in rough water. That the Admiralty was already thinking of taking men off the beaches in shallow water had of course not yet occurred to anyone, let alone that they would have to evacuate nearly 400,000 of them. It would have been still harder to imagine that only ten days later Ockie’s neighbor’s yacht would be sailing the eighty-seven nautical miles of “Route Y” from Dover to Dunkirk, more than twice the length of the direct crossing “Route Z,” but a course that Admiral Ramsay would be obliged to choose after the Germans took Calais, putting British ships and boats within the range of German guns on the shorter course. Stranger still, though considerably the worse for wear, she was delivered back by the navy, and stayed tied up at Teddington until after the war, since there was no gasoline for her. I saw her there myself, in 1947.

Although Hungary is a landlocked country, my father and his two brothers were “good sailors.” None of them was ever seasick, even in storms that sent other passengers groaning to their beds on Channel or Atlantic crossings. On the other hand, my father would have had no interest in going up and down the Thames in my grandmother’s company. He was, in fact, busy sorting out a naval problem of his own. That Hamilton Woman (it did not yet have that title, being still a screenplay in the making), the story of the love affair between Nelson and Lady Hamilton, would require the reenacting of the Battle of Trafalgar. This kind of thing is usually done by using small models, often with a matte shot to provide the sea in the foreground, but the result is never very convincing on the screen. Since the film was being made at Winston Churchill’s suggestion. Alex was determined to make the naval scenes look as convincing as possible. “Special effects” and what was then called “trick photography” did not particularly interest him, but he was not unfamiliar with that kind of thing either. After all, The Thief of Baghdad, still being worked on, was a triumph of trick photography, perhaps even the triumph (it would win the Academy Awards for Special Effects and for Photography in 1940, as well as my father’s Academy Award for Art Direction),* and as early as 1919 Alex had directed a futuristic Jules Verne science fiction novel on the Dalmatian seacoast as well as the biblical epic Samson und Delila in Vienna, which required sophisticated trick photography for the time, for the big scene in which Samson pulls the temple down on top of the Philistines.

Fortunately for Vincent he could draw on the advice of William Cameron Menzies, whom Alex had brought over to England from Hollywood to direct Things to Come and whom he brought back over despite the war to solve some of the many problems of The Thief of Baghdad. Jock Menzies was a difficult man and something of a genius—he was perhaps the man most responsible for pulling together the enormously complicated production of Gone with the Wind for David O. Selznick—and the first person in Hollywood to bear the title “production designer,”† but far from being rivals, he and my father had a deep professional respect for each other, and even a certain fondness.

The solution they came up with—helped by suggestions from Ned Mann, perhaps the most skillful designer of optical special effects in Hollywood—was to make the boats bigger, much bigger. Small model ships when photographed tend to move in an artificial straight line, drawn across on wires, but real sailing ships move with the waves, pitching, tossing, and heeling as they move. The solution was to build model ships of the line about the size of a dinghy, big enough to hold (and conceal) two prop men, who could furl and unfurl the sails, fire the guns and simulate damage by pulling down masts or spars.

Who came up with the idea of having the legs of prop men, encased in rubber fishing waders, stick down below the waterline of the dinghy so that they could walk it along with their feet on the bottom of a large, shallow tank, I do not know. Probably Menzies. Ned Mann came from Indiana, where he was unlikely to have been exposed to dry-fly fishing, still less my father, born on the vast plains of Hungary. In any case, the problem was solved, except for the fact that no such tank existed in England and that, in 1940, it was not possible to build a whole fleet of working model ships in a country gearing up at last (and possibly too late) for total war. The craftsmen who would have produced the model ships were busy making Fairmile motor torpedo boats or learning how to put their woodworking skills to the production of a revolutionary all-wood high-speed bomber, the de Havilland Mosquito.

By an odd coincidence the length of the model ships required for That Hamilton Woman was about fifteen feet—almost exactly the length of the smallest of the “little ships” that would be used to evacuate troops from the beach at Dunkirk, the celebrated Tamzine, a clinker-built fishing boat from Margate with a sail and a small outboard motor, which is now preserved at the Imperial War Museum in London.

It must have seemed unlikely to my father that anything on this scale could be accomplished in England, in the spring of 1940, still less the many “retakes and added scenes” demanded by Alex for The Thief of Baghdad. For Alex filmmaking was a constant process of revision and second thoughts, whatever they cost—and the cost was enormous because the actors, their costumes, and the sets had to be reassembled for each scene, at great (and expensive) inconvenience to everyone.

In this case it was the money of the normally cautious Prudential Insurance Company, which had been investing in his films since the midthirties apparently without learning any lesson from its experience, and United Artists, of which Alex was a director and by a complicated series of transatlantic business maneuvers part owner. Alex not only had to find a way of finishing the film; it had to be a huge hit, and a good part of the responsibility for this rested on my father’s shoulders.

It was a stressful time for the Kordas even without taking into account the events taking place on the other side of the Channel. About these, my uncle Alex was more pessimistic in private than he was in public. He knew and loved France, he had made films successfully there, France was one of the biggest overseas markets for his films (after the United States and, until 1933, Germany). The London Films office in Paris on the Champs-Elysées was even larger than his office in Rockefeller Center, and many of those who worked there worked for MI6 as well as Alex. France was, and would remain after 1945, a second home to him, as it did to my father, but he understood better than many people the deep ambivalence with which the French faced the war. He understood that nobody in France had wanted war and that everybody was determined not to repeat the carnage and destruction of the previous one—above all France was not an island and there was no Channel to separate the French from the Germans.

The British might defend themselves with their navy and their air force for a time, perhaps forever, the Americans and the Russians might sit the war out, but France would be engulfed if it lost the battle that was taking place in the last week of May 1940. Talking to his many friends in France, Alex drew his own conclusions about what was happening there, based on having lived in the Austro-Hungarian Empire as it faced defeat in 1918: a fatal combination of defeatism and light-headedness, such as one might feel going down the last sickening drop in a roller-coaster ride if there were no end in sight, and no way to stop or get off. The national motto might as well have been “Tout s’arrangera,” a desperate belief that in the end reasonable people would make a deal, without taking into account that not only Hitler but the Nazi Party itself and perhaps the German nation was no longer reasonable.

Alex knew that, too. He had worked in Berlin in the 1920s, he had attended the frenzied first night of Brecht and Weil’s Die Dreigroschen Oper, with jackbooted Brownshirts howling, throwing rocks and bottles, and trying to drown out the music with chants and curses, and he understood down to the marrow of his bones what was in store for everyone if the Germans won, yet he did not dislike the Germans, or think of Germany as an alien, foreign country—German was his second language, the years in Berlin had been, if not the happiest then certainly the most productive of his life. His friends included pro-Nazis like Leni Riefenstahl and Luftwaffe General Ernst Udet, on whom Carl Zuckmayer based his play and subsequent film The Devil’s General, and also vehement anti-Nazis like Marlene Dietrich and Lotte Lenya. For him, my father, and my uncle Zoltan, Germany was not an abstraction; all three of them spoke German as well as they spoke English or French. They were fiercely opposed to Nazism, as they were to the fascism of Horthy’s Hungary, but they remained sympathetic toward individual Germans, unlike so many people in England who turned against German culture altogether.

Marlene Dietrich.

Leni Riefenstahl.

The Kordas were not alone. A good part of the German film industry had moved to Paris, London, or Hollywood in the years since 1933, among them Otto Preminger and Billy Wilder, whose barber at the Adlon Hotel in Berlin, a Nazi Party member, had tipped him off to get out of Germany while shaving him in the morning. Wilder took his barber’s advice seriously, and said he would go back up to his suite and pack. The barber shook his head sadly. “I wouldn’t do that, Herr Wilder,” he said, “I would go straight to the station.”

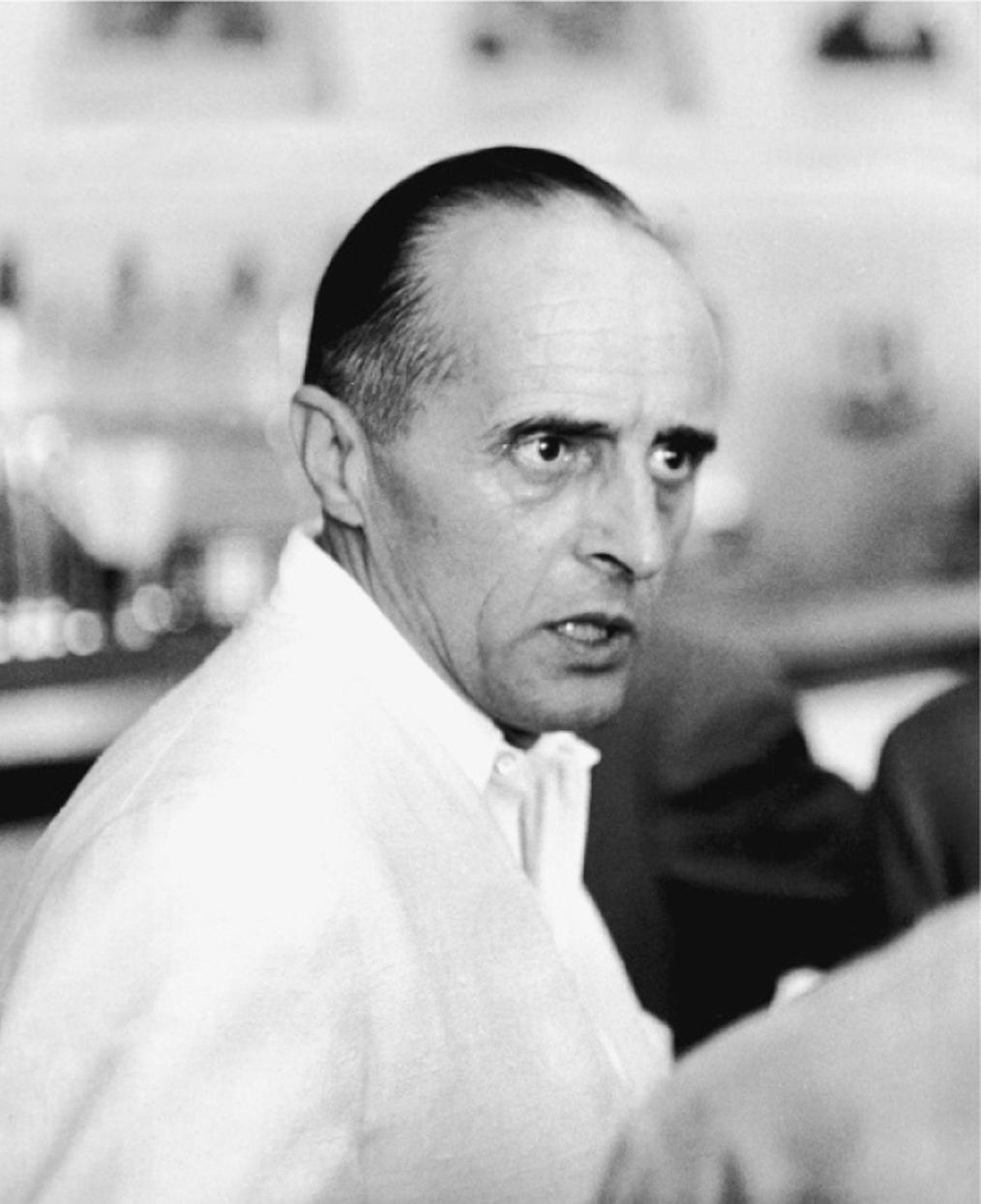

Otto Preminger arrives in Los Angeles.

Germany had always played a huge role in film production and still loomed large in the mind of many people. When Preminger finally got to Los Angeles, he used to eat dinner sometimes at a Viennese restaurant on Santa Monica Boulevard called (of course) The Blue Danube. Sitting there at the bar one evening he heard a lot of the Hollywood Hungarians chattering away in Hungarian at a nearby table. Preminger got more and more annoyed, and finally he banged his glass down on the bar, turned around, and shouted at them, “Alright, you guys, knock it off, you’re in America now—talk German!”

My father would have certainly understood that. Wherever he went, he remained a European. I remember him staring glumly at the Times. He was not as privy to inside information as his brother Alex was, but he was shrewd enough to tell the difference between propaganda and fact, besides which many of the friends he worked with were French filmmakers like Georges Périnal and René Clair. The French could tell from the license plates of refugees arriving in Paris by car just how badly things were going,‡ and with the ingrained cynicism that is part of the French national character they assumed that their government and their press were lying to them, and that however bad things looked, they were actually worse.

French director René Clair.

My mother, when she thought about the war at all, had the cheerful conviction that everything would work out well in the end because it always had for Britain, except for the war against the American colonies, and that was too long ago to matter. Far from being depressed, she was exhilarated. Even so staid a newspaper as the Times hailed the “hundreds” of enemy aircraft shot down by the RAF and by the Armée de l’Air (the latter had already virtually ceased to exist), and on May 27 headlined that “THE B. E. F. FRONT REMAINS INTACT,” though it was already shattered, and praised the resistance of the Belgian Army, which was in fact laying down its arms and would surrender unconditionally the next day. Reading about these nonexistent triumphs of the Allied armies, my father shook his head sadly as he read one story and muttered, “This is all some nonsense of Brendan’s.”

He was right, of course. Brendan Bracken was Duff Cooper’s closest confidant, and with the shrewd judgment which he always had about the public’s mood he was about to oversee a switch from overconfidence to frank realism, at just the right moment in time. The government was about to try a new and novel means of maintaining British morale, betting on the common sense of the British people when faced with disaster: to tell the truth.

_________________________

* By an odd coincidence The Thief of Baghdad was released on the same date as that other masterpiece of trick photography and imaginative filmmaking The Wizard of Oz. Odder still, neither one hurt the other at the box office—they were both huge hits.

† An “art director” designs and decorates sets for a motion picture. Menzies (and later my father) as the “production designer” had a direct influence on the whole look of a film, often painting a series of panels showing each important scene in a film and how it would be lit and photographed. My father had started doing this for The Private Life of Henry VIII and would be responsible for much of the visual impact of The Third Man.

‡ There was a different two-number code for each départment in France—“75,” for example, stood for Paris, “06” for the Alpes-Maritimes—so it was possible to tell from the license plates of civilian refugees how much farther the Germans had advanced than the newspapers or the government admitted.