British troops prepare to defend a position.

“Presume Troops Know They Are Cutting Their Way Home to Blighty”

British troops prepare to defend a position.

ON MAY 25 Lord Gort, acting on his own, seems at last to have made the critical decision to evacuate the BEF. He started one of his divisions moving north toward the sea, instead of toward the south, where, it was painfully clear to him, the French attack from the Somme toward Cambrai, the so-called Weygand Plan, was never going to take place. At the same time, the Belgian forces on his left were inert or crumbling.

Gort was acutely conscious of the fact that the survival of the BEF was his first responsibility, and he had already begun the process of “thinning out” the “useless mouths” of the army by evacuating them from Dunkirk—there was no further use for gunners* without their guns, or for any of the numerous nonfighting troops of a modern army (known officially as “Line of Communications troops” or more colloquially as “odds and sods”), still less for the numerous (and mostly unarmed) members of the RAF who had been separated from their squadron or unit as the RAF tried to withdraw from airfields and supply depots that could no longer be held.

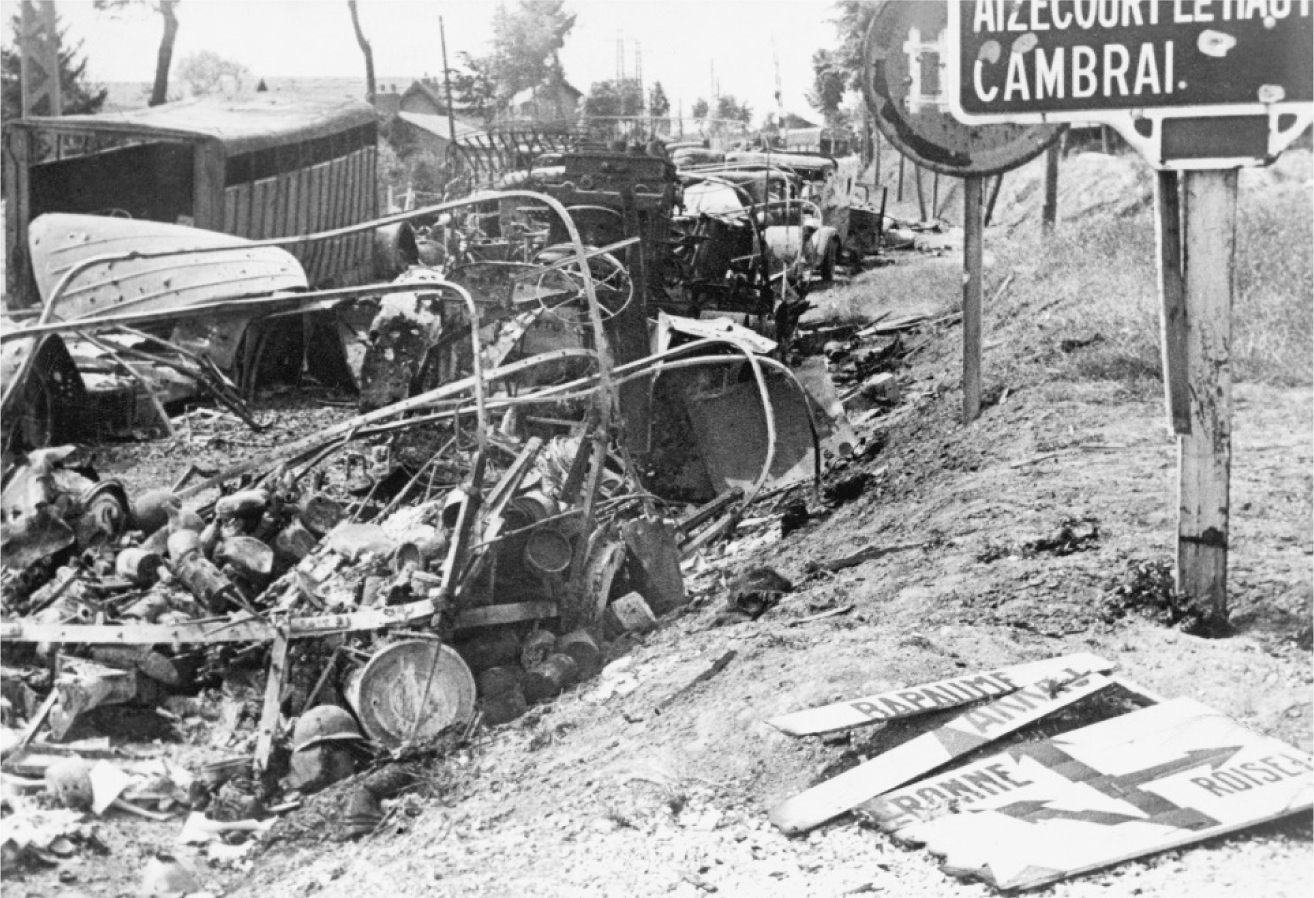

Remains of a British convoy after being attacked by Stuka dive-bombers.

With the fall of Calais and Boulogne the BEF had no port left to go to except Dunkirk, and even that was by then reduced to a wretched hell. Heavily and continually bombed, it no longer had electricity, which put its cranes out of action, there was no water, and its streets were blocked with rubble and broken glass. “It is all a first-class mess-up,” wrote General Pownall, “and events go slowly from bad to worse, like a Greek tragedy. . . .” For once Pownall was overoptimistic—events were not going from bad to worse “slowly,” they were hurtling downhill very quickly indeed.

So little was heard from the Belgians on the British left that the 12th Lancers, “always most reliable,” were sent off to look for them, but for all practical purposes the Belgians had simply stopped fighting, and the French First Army, in the words of one of its senior officers, “N’éxiste plus.” As always, Henry de La Falaise accurately describes a day of bloody chaos as the 12th Lancers’ armored cars advanced almost twenty-five miles in search of the Belgian Army despite constant bombing and machine-gunning from the air. They met up with a Belgian artillery supply unit, whose “terrified horses [were] milling around wildly, neighing with fear and running into the barbed wire fences as they try to get away,” and masses of disorganized traffic and refugees in wagons blocking the roads. The only Belgian fighting troops the 12th Lancers encountered were in retreat, many without their weapons, but by then so was almost everybody else, except in rare places where the French made a gallant, but futile, stand against impossible odds. Once darkness fell, it took the 12th Lancers two hours to cover twenty miles—no one could use headlights, and every road, field, and village was blocked by trucks, fleeing civilians, artillery, and infantry, the total confusion of defeat. Eventually, they managed to report all this back to BEF headquarters, itself on the move, and were ordered to withdraw to the northwest.

Halting for a day to service their vehicles and clean their weapons—the mark of well-trained regulars—they received orders to move on and patrol the Loos Canal. La Falaise was shocked at the sight of the Furnes highway leading to it: “It recalls the paintings of Napoleon’s retreat from Russia. Brand new trucks, tractors, guns of every caliber, line the ditches and fields. Millions of dollars worth of entirely new British equipment lies in the mud. . . . It is a horrible and disheartening sight.” A British staff officer caught up in the retreat wrote later that he asked a French officer when the French offensive would begin. The latter replied, “ ‘Not yet, the armies are épuisées.’ Surely the Germans must be exhausted too, the British officer suggested? ‘But they are drunk† with success, and we are sober with defeat,’ the Frenchman said, ‘and the drunkard has the strength of seven men.’ ”

German troops restring electric wires near Dunkirk using a captured British vehicle.

To be fair, most of the BEF had not yet been as hard-pressed as the French and the Belgians, nor was their country (as was the case with Belgium) or a significant part of it (as was the case with France) already occupied by the Germans. Nobody in the BEF had lost his home, his place of work, or his farm to the enemy. To most of the Belgians, and a good many of the French, the war was already lost, the future an uncertainty or a catastrophe—not circumstances likely to provoke a determined last stand against an enemy that had already proved itself superior in weapons, training, zeal, and leadership.

It is worth noting that despite the grousing and complaining about the Belgian Army from British soldiers of all ranks at the time (and from British historians ever since), Belgium fought for over two weeks with a poorly armed, led, and equipped conscript army against the full force of General von Bock’s Army Group B. Militarily, there may not have been much to praise about the conduct or the morale of the Belgian Army, but it (together with the much maligned French First and Seventh Armies) slowed Bock down long enough to enable the BEF to reach Dunkirk more or less intact. Once an army has been pushed back out of its own country, its fighting spirit is in any case likely to collapse like a punctured soufflé and the Belgian Army was no exception. Then too, unlike the British, the Belgians and the French were not regular troops (or part-time volunteers, like the British Territorials), they were conscripts who were anxious to get home, and for whom the war was all but over. The German superiority in tank tactics and especially their sophisticated use of radio communication at every level to concentrate tanks, motorized infantry, artillery, and aircraft on a single point with devastating speed and power had overwhelmed conventional troops as well as their bewildered commanders.

Above all, the seemingly constant presence during daylight hours of Stuka dive-bombers attacking almost without opposition broke whatever fighting spirit was left among troops who had expected to wage war defensively from prepared positions (as in the First World War) and instead found themselves scattered along the roads among the refugees, and bombed day or night wherever they paused. A war of movement exposed not only the weaknesses in the Allied armies but the deficiencies and unwieldiness of their chain of command.

German control of the air had further demoralized them. Belgium’s air force had been destroyed on the ground, France’s air force had disintegrated almost at once, just as everybody in the know in French political circles had predicted it would, since it was equipped with inferior, outdated aircraft and had no modern integrated system of command and control.

Even in the BEF confidence in the Royal Air Force was plummeting. However superior British fighter aircraft were, all that the men on the ground saw was the unrelenting, uninterrupted attack of German bombers and dive-bombers. They seldom saw the “dog fights” going on high above them or appreciated the immensely high losses among the Battle or Blenheim bomber squadrons—on May 14, for example, forty out of seventy-one RAF aircraft sent to bomb German bridges over the Meuse were shot down, an unsustainable rate of loss. Given the exaggerated fear of “fifth columnists”‡ and German parachutists—in fact the whole German parachute force had been used to capture the vital Dutch and Belgian bridges on May 10—British airmen obliged to bail out were frequently treated as the enemy even by their own countrymen, and sometimes threatened with being shot by Belgian and French troops. It did not help matters that Luftwaffe and RAF uniforms and flying suits looked similar. Ironically, the RAF, which would achieve its moment of greatest glory only three months later in the Battle of Britain, had now reached a nadir of popularity among the troops such that the prime minister himself would feel obliged to deal with the matter—RAF personnel were being insulted and even “roughed up” by angry soldiers, thanks to the ubiquity of German aircraft.

La Falaise describes the common experience of a sudden attack by German aircraft in broad daylight: “Geysers of earth and tongues of flame leap into the sky. For three minutes or more, that seem endless, I cower under a wall holding my breath, my legs shaking, while houses to the right and left are smashed to the ground. Two hundred yards up the road a convoy of more than twenty ammunition trucks is hit repeatedly and blows up with a deafening explosion. Shells and men’s bodies fly through the air. The ammunition cases keep on exploding an hour after the planes disappear, making it impossible for anyone to rescue the wounded.”

Again and again one is struck by the fact that the Germans had spent nearly two decades thinking out every detail of the attack against France and the Low Countries with single-minded Teutonic efficiency. As airfields were captured, improvised teams of men quickly installed radio communication and erected repair facilities; as soon as they were done, the lumbering but reliable Ju 52 transport aircraft (the German equivalent of the Douglas DC-3 “Dakota,” which would become ubiquitous in the same role after the United States entered the war) flew in specialists, fuel, and ammunition; thus the German air force leapfrogged directly behind the fighting troops, and was able to deliver aircraft like runners in a relay race. A squadron would attack, and while it was flying back to refuel and rearm, another would take its place, a constant, rolling delivery line of death and destruction.

British and French strategists (except for contrarians like Fuller and de Gaulle) had never anticipated this kind of efficiency, in which the aircraft were based right behind the front line and in constant radio communication with troops on the ground, so that a regimental commander could summon up waves of dive-bombers instead of waiting for artillery to be brought up. It had been considered impossible to supply aviation fuel to such advanced airfields, but the Germans simply flew it in and, what’s more, had designed the twenty-liter stamped and welded steel “jerrycan,” with its built-in pouring spout and leak-proof snap closure, which would soon be adopted by every army in the world, allowing them to move large quantities of fuel quickly, safely, and easily, at a time when everybody else was still using flimsy stamped tin containers that required a wrench and a funnel and leaked like a sieve.

Even somebody as practically minded as Churchill had supposed that German tanks would outrun their fuel supply quickly, without taking into account the mass production of the jerrycan—or the fact that Rommel moved so fast that he simply had his tanks stop and refuel at gas stations on the road, as if they were cars. It was not so much that every German weapon was superior as that each piece of their war machine, however small, fit into place like the pieces of a jigsaw puzzle, and that everything was built around the concept of movement. Whereas the French had put their money between the wars into the Maginot Line, as imposing and as firmly fixed in place as the Pyramids, the ultimate expression of defense, the Germans had instead built a functioning modern war machine—their mantra was mobility, its purpose was to attack.

On Sunday, May 26, General Lord Gort informed the secretary of state for war of his decision, with a certain degree of restraint: “At present we are strung out on immense front and great majority of force is in close contact with the enemy. There are not sufficient reserves with which to make a hole for a break. Some withdrawal essential. . . .” The word “Some” was a vast understatement. General Pownall commented to himself, more frankly, “Whether we ever get to the sea, how we get off the beach, how many of us survive is on the knees of the Gods. But it is the only thing to be done. We cannot stay here without being surrounded and there is no other direction in which to go.”

By now, a note of caution and common sense had been sounded in the British War Cabinet too. The prime minister remarked, “It seemed from all the evidence available that we might have to face a situation in which the French were going to collapse, and that we must do our best to extricate the British Expeditionary Force from northern France.”

It was a busy day for Churchill. To begin with, it had been declared a National Day of Prayer, a suggestion that the king had made three days before, and which rendered the prime minister’s presence in Westminster Abbey necessary for ten minutes during the service—the closest he could cut it. Churchill had not been enthusiastic about the king’s idea, concerned that a day of national prayer might be seen as an admission of fear or defeatism by the enemy. He was not in any case an enthusiastic churchgoer—Churchill dutifully attended formal events that involved the church, weddings, funerals, christenings, and coronations, but observed of the Church of England that he “supported it from the outside, like a flying buttress.” Like a former prime minister, Lord Melbourne, who had found the appointment of bishops one of the most burdensome duties of his office (and complained that they died only to annoy him), Churchill was without religious instincts,§ and did not suppose that a church service, even one involving the king and the archbishop of Canterbury, would improve Britain’s military situation. However, he had to go despite his grumbling, as Mrs. Churchill pointed out to him.

More on his mind that day was the fact that he had decided to replace the chief of the Imperial General Staff, General Sir Edmund Ironside, with General Sir John Dill, the vice-chief and a former corps commander of the BEF, an odd decision since Churchill rather liked Tiny Ironside and thought Dill was unimaginative and “a dinosaur.” It may have been a reflection of the intense French dislike of Ironside, who had not bothered to disguise his contempt for the French generals, or of a growing expectation on Churchill’s part that a German invasion of Britain would follow a French collapse and that Ironside, with his bluff, untactful nature, was the right man to knock heads together and improvise an effective defense. If so, he would be disappointed—Ironside rubbed his generals the wrong way in his new role as commander in chief, Home Forces, and Dill was not transformed by his promotion into the CIGS that the prime minister was looking for. Fortunately, the headlines about the German advance to the sea rather overshadowed the stories the next day about this hasty change in command.

Even bigger challenges faced Churchill early in the morning on May 26, starting with an alarming surprise: a telegram from Premier Reynaud that he was flying to London that day and “wished to meet with the Prime Minister alone, or perhaps with one other Minister present only,” surely a sign that the French were already thinking about surrender. More depressing still was a message from Admiral Keyes that the king of the Belgians had decided “not to desert his army” and join his government in exile, and had written a personal letter to King George VI explaining his motives—king to king, as it were. A Belgian surrender, which was clearly imminent, would leave the left flank of the BEF wide open as it withdrew toward Dunkirk.

The message that Premier Reynaud flew to London to deliver to the prime minister personally over a hastily arranged lunch à deux at Churchill’s flat in the Admiralty was not quite yet a counsel of despair, but it was not far from it. A week ago Reynaud had asked Marshal Pétain to return from Madrid, where he had been serving as French ambassador to Franco’s Spain, and join the cabinet as deputy prime minister. The camel’s nose was therefore already inside the tent—Pétain’s pessimism, his vanity, his dislike of the British, above all his belief that the war had already been lost and should never have been begun in the first place had already affected the French government and undermined Reynaud’s tenuous control of it. Reynaud’s message reflected, however hard he tried to conceal it from Churchill, the rapid metastasis of French defeatism.

The message contained two separate parts, the first of which was to become the theme of every Franco-British meeting over the next two weeks: the French did not think that they could continue the war for much longer unless the British threw in all of Fighter Command at once—or unless the United States joined the war. The latter was of course beyond Churchill’s control, and he strongly doubted that President Roosevelt could or would declare war against Germany, something he was in a good position to judge since he was in constant correspondence with the president and received frequent warnings on the subject from Ambassador Kennedy as well. As for the former, it would entail giving up any chance of defending Great Britain.

The fact that Fighter Command could not operate from makeshift airfields under German attack, and that it was dependent on a vastly complex system of radar observation and bombproofed, centralized communication was not discussed—radar was too secret to talk about, and in any case the prime minister himself had not yet fully understood the sheer complexity and sophistication of Britain’s air defenses, of which the fighters themselves were only the most visible and glamorous part.

The second French request was for an immediate approach to Mussolini to prevent Italy from joining the war, in return for which Britain and France might offer to address some of Mussolini’s demands in the Mediterranean—Reynaud rather vaguely alluded to the demilitarization of Suez, Gibraltar, and Malta, and to Italian claims to France’s colony in Tunisia as possibilities for discussion. Churchill had a guarded respect for the man he called “the Italian lawgiver,” whom he had met, but was not about to hand him control of the Mediterranean on a silver platter in return for a promise that Italy would stay out of the war.

It may seem odd, in view of the future performance of the Italian armed forces, that Mussolini’s threat to enter the war was taken so seriously, but there was certainly something to be said for keeping Italy out of it. This would not only free up ten French divisions that were standing guard idly along the Franco-Italian border but, much more important, prevent the war from spreading to the Mediterranean when Allied forces were already stretched to (or beyond) the breaking point in northern France. Francophile though he was, the prime minister could hardly fail to notice that in the long tradition of Anglo-French diplomacy Reynaud was in effect proposing to buy peace with Italy in British coin—Suez, Malta, and Gibraltar.

Churchill disputed most of this, firmly but in good temper. He tried to raise Reynaud’s spirits by saying that once the situation in northeastern France had been “cleared up,” he thought the Germans would attack Britain next rather than break through the thinly held French line and go for Paris. Reynaud was not persuaded. It was “the dream of all Germans . . . to conquer Paris,” he replied, correctly and with implacable French logic, and therefore “they would march on Paris.”

Unfortunately no record of the conversation between the two prime ministers exists. Reynaud did not write about it until 1951, whereas Churchill came straight back from the lunch to tell the rest of the War Cabinet what had been said. That the War Cabinet resumed at 2 p.m. would seem to indicate that lunch was a hasty meal by Churchill’s standards, and probably by those of Reynaud too. Sadly, it was a Sunday and Churchill’s invaluable (and observant) young private secretary John Colville was away for the day in Oxford, flirting with Chief Conservative Whip Captain Margesson’s daughter Gay—they dined together at the seventeenth-century pub and restaurant The Trout, by the Thames, still a wonderful restaurant even in my own days at Oxford—so we have no idea what kind of meal was served to Reynaud. In any event Churchill ended it by asking Reynaud bluntly whether any peace terms had been offered to France, and Reynaud, surely with some embarrassment, replied evasively that none had been so far, but that he knew he could get an offer if he wanted one.

John Collville.

Churchill asked Halifax, Chamberlain, and Attlee to go over to the Admiralty and talk to Reynaud before he returned to Paris, but not before the crucial question came up that would dominate the next forty-eight hours politically. The minutes of the War Cabinet note rather modestly, “A short further discussion ensued on whether we should make any approach to Italy,” without much detail. We know from the record that the prime minister “doubted whether anything would come of an approach to Italy,” while the foreign secretary (Lord Halifax) “favoured this course” and thought that the last thing “Signor Mussolini” would want was “to see Herr Hitler dominating Europe.”

This was a substantial difference of opinion, particularly since Halifax had already met with the Italian ambassador, Count Giuseppe Bastianini, to discuss not only the question of keeping Italy out of the war but the much bigger one of persuading Mussolini to ask Hitler what his terms for peace might be, or as Bastianini put it more diplomatically (as reported in the cautious words of Halifax) of not excluding “the possibility of some discussion of the wider problems of Europe in the event of the opportunity arising.” Since Mussolini read and initialed Bastianini’s report on the conversation, it was clear to him that Halifax was proposing that he repeat his bravura performance as the man who saved the world from war by sponsoring the Munich Conference in 1938, this time by bringing the warring parties to the conference table in May 1940.

Such a reprise would no doubt have appealed to Mussolini’s colossal vanity, had he not already pledged to Hitler that he would join the war just as soon as the creaky stage machinery of the Italian armed forces could be moved into action of some sort—indeed any sort. Besides, Mussolini had already calculated that Germany was winning the war, had already as good as won it in fact, and that he would get a better share of the spoils if he came in as soon as possible on the German side—his only anxiety was that the French and the British might surrender before he could declare war, in which case Italy might get nothing, a concern made more acute by Hitler’s apparent indifference to whether Italy joined in the war or not, and by the unmistakable hostility and contempt toward Italy of the German generals, who had no desire to add the Italian Army’s logistical problems to their own.

One thing is certain, that Hitler already had learned from Rome that Halifax (and, he may have supposed, perhaps other members of the War Cabinet) was seeking a negotiated peace, “not merely an armistice but [a settlement that] would protect European peace for a century,” to quote Bastianini’s overinflated hopes. The same message was also reaching the Führer from Paris, via Rome, perhaps clouding his judgment momentarily.

Significantly, Churchill sent Halifax, Chamberlain, and Attlee off to the Admiralty with instructions to get Reynaud to have General Weygand order the BEF to march to the coast, so the French could not afterwards complain that they had not been informed, or that the British had let them down. Unlikely as it was that Weygand would oblige (or that the French would take any notice), Churchill told the secretary of state for war, Anthony Eden, to draft an order at once for General Gort to march to the coast and begin the evacuation of the BEF.

The War Cabinet resumed at 5 p.m. and Churchill was momentarily obliged to struggle against Halifax’s desire to explore a negotiated peace, no doubt reinforced by his discussion with Premier Reynaud. The prime minister said “that we were in a different position from France. In the first place, we still had powers of resistance and attack, which they had not. In the second place, they would be likely to be offered decent terms by Germany, which we should not.” He did not wish to be forced into “a weak position in which we went to Signor Mussolini and invited him to go to Herr Hitler and ask him to treat us nicely.”

Halifax rejected this view. He thought it would be better to allow France “to try out the possibilities of European equilibrium,” exactly the kind of diplomatic doubletalk that was likely to irritate Churchill. Halifax then remarked that he “would not like to see France subjected to the Gestapo.”

Churchill dismissed this brusquely as unlikely.

Halifax replied that he was not so sure. He had not yet discovered that, unlike him, Churchill enjoyed arguing and that his opponent’s arguments bounced off him like tennis balls aimed at a tank.

The line was now clearly drawn between them—there was a fissure in the War Cabinet, and Halifax felt obliged to put the argument against continuing the war to his fellow members of the War Cabinet. Unlike the prime minister, Halifax had taken full measure of Reynaud’s report of the hopelessness of the French position, nor did he share Churchill’s zest for battle or his experience on the battlefield of wringing victory from apparent defeat.

Churchill’s reply was blunt and unambiguous. He thought it was best “to decide nothing until we saw how much of the Army we could re-embark from France.” That operation, he thought, “might be a great failure.” On the other hand, “our troops might fight magnificently and we might save a considerable portion of the Force.” He ended the discussion—for the moment—with a flourish. “Herr Hitler,” Churchill said, “thought he had the whip hand. The only thing to do was to show him that he could not conquer this country.”

Admiration for the new prime minister was not yet universal. Sir Alexander Cadogan, permanent undersecretary at the Foreign Office, who attended the War Cabinet that afternoon, remarked in his diary that Churchill was “too rambling and romantic and sentimental and temperamental,” a view that Halifax certainly shared, or at least with which he would have sympathized. “Old Neville still the best of the lot,” Cadogan concluded, an opinion still shared by most Conservatives.

That evening Captain Claude Berkeley, a member of the prime minister’s military staff, reported an impression different from that of Cadogan: “Reynaud was not impressive. The PM was terrific, hurling himself about, getting his staff into hopeless tangles by dashing across to Downing St without a word of warning, shouting that we would never give in, etc.”

At 7 p.m. Churchill gave the crucial order to begin Operation Dynamo, Vice-Admiral Ramsay’s plan for the evacuation of the BEF.

Late that night he sent a message to Lord Gort, whose army was moving in chaotic conditions and under constant attack toward Dunkirk, where the harbor was already being shelled by at least forty German guns. “At this solemn moment I cannot help sending you my good wishes. No one can tell how it may go. But anything is better than being cooped up and starved out. . . . Presume troops know they are cutting their way home to Blighty. Never was there such a spur for fighting. We shall give you all that the Navy and the Air Force can do.”

_________________________

* In the British Army many formations do not use the rank “private.” A private soldier in the Brigade of Guards is called a “guardsman,” for instance; in the cavalry (and armored forces) a “trooper”; in the Royal Artillery a “gunner”; in the Royal Engineers a “sapper”; in rifle regiments, a “rifleman”; in fusilier regiments, a “fusilier”; etc.

† Epuisé means exhausted, but can also be a polite euphemism for drunk.

‡ A phrase from the Spanish Civil War, when Fascist General Emilio Mola claimed that in addition to four columns of troops attacking Madrid he had “a fifth column” inside it. The notion of an elaborate organization of German troops in civilian clothes (“storm troopers” disguised as nuns was a favorite example) or German-sponsored civilian snipers and saboteurs was widespread in 1940, but there is very little concrete evidence that it really existed, although a good many unlucky people were summarily executed for belonging to it.

§ Churchill neatly summed up his religious beliefs himself: “I am prepared to meet my Maker. Whether my Maker is prepared for the ordeal of meeting me is another matter.”