Obergruppenführer Sepp Dietrich and Himmler.

Obergruppenführer Sepp Dietrich and Himmler.

AT 10 P.M. on Sunday, May 26, Vice-Admiral Sir Bertram Ramsay received the order from the Admiralty to commence Dynamo. Ramsay’s mind was eminently practical—he had chosen Dynamo as the code name for the evacuation not because it connoted rapid movement or power but simply because his office in one of the tunnels of the White Cliffs of Dover was close to another containing the emergency generator. He set in motion his forces for Dynamo in the same practical spirit.

Although Churchill clung to the belief that Weygand’s planned attack would actually take place until the last possible moment, the vice-admiral Dover had already long since concluded that evacuation might be necessary. On May 15, when the Germans had just crossed the Meuse and the BEF was still digging in at the Dyle line in Belgium, Ramsay had set in motion the “Census of [civilian] Motor-boats,” the first essential step to gathering together every ship and boat that might be needed, and on May 19, in a meeting at the War Office, he brought up “the problem of the hazardous evacuation of very large forces.”

Ramsay was not only farsighted; he was as a senior naval officer accustomed to making decisions on his own—the captain of a ship cannot always wait for orders or ask for them to be explained—and something of a buccaneer. The naval force he commanded as the vice-admiral Dover was small compared with the importance of his post, only eighteen destroyers and a mix of minesweepers, trawlers, “armed boarding vessels,” and train ferries converted into minelayers, but he had used his destroyers daringly, slipping them into the port of Ijmuiden under the guns of the Germans to bring off the Dutch royal family and government, as well as all the Dutch gold reserve and a large stock of diamonds.

On May 24 Ramsay met with the vice-chief of the French Naval Staff, Admiral Auphan, and the Amiral Nord, Admiral Abrial. Both French admirals were, or pretended to be, shocked and angered by Ramsay’s frank discussion of his plans for evacuating the BEF from Dunkirk. They had in mind defending Dunkirk as a kind of fortified bridgehead, supplied from England. Ramsay, with some difficulty, attempted to smooth their ruffled feathers, though he did not succeed in convincing Abrial, who would stay on to the very end in his underground headquarters at Dunkirk attempting to defend the city, while communicating as seldom as possible with his British allies—a fatal breach. Even among admirals, a notoriously tough bunch, Admiral Abrial was a tough nut to crack, and like most, if not all, French senior naval officers he regarded Britain as France’s hereditary foe. The Germans were merely a coarse and unwelcome interruption in a naval rivalry that had been going on since the early eighteenth century.

It is worth noting that Ramsay was preparing for Dynamo and discussing it with the French admirals a day before Lord Gort reluctantly reached his decision to retreat to the coast, and three days before Ramsay actually received the order to begin it. Photographs of him portray a calm, sturdy, realistic judge of events, feet spread as if he were on the bridge of his ship, unlikely to be swayed by rhetoric or windy emotion—in short, the perfect man for the job. It is some measure of Ramsay’s organizational ability that within three days of the order to begin Dynamo he would put together a fleet consisting not only of warships but of almost everything that would float, including the lifeboats from ocean liners and freighters moored in the London docks, yachts, barges, paddle-wheel pleasure steamers, fishing trawlers, tugs, ferries, a London fireboat, and Dutch schuits (broad-beamed Dutch canal boats), a total of over eight hundred recorded vessels. He would also acquire a couple of hundred more privately owned vessels, among them Sundowner, a fifty-eight-foot yacht owned by Charles Lightoller, the retired second officer of RMS Titanic, who sailed her himself to the Dunkirk beaches aided by a crew consisting of his eldest son and a teenaged Sea Scout, and Medway Queen, a Thames paddle-wheel pleasure steamer, which made seven round-trips to the beaches, brought back seven thousand men, was credited with shooting down three enemy aircraft, and ended her career moored as a floating nightclub. Some of the bigger ferries that served the Isle of Man or the Channel Islands were diverted to Dunkirk with their white-jacketed stewards still ringing a little silver bell to announce that tea was being served in the saloon (for officers, rather than first-class passengers), or drinks and sandwiches.* Some of the larger ferries had been converted into hospital ships, painted white with conspicuous red crosses on the hull and funnel, but this did not protect them from being bombed or shelled by the Germans.

Ramsay had already succeeded in getting 27,936 “non-fighting troops,” as the official British war history calls them, out of Boulogne, Calais, and Dunkirk before Dynamo had even begun. Many of these were taken off the eastern mole of Dunkirk’s outer harbor, a long stone-and-wood structure ending in a wooden jetty. Dunkirk was not then the modern port it has since become, nor was it a particularly convenient one from which to evacuate a large number of men. The entrance to the outer harbor was narrow, formed by two moles running out to sea at an angle of about forty-five degrees to each other like a giant funnel, its spout pointing out to sea, its wider end opening out as one approached the inner port, and leading to a longer and even narrower entrance to the docks themselves, which formed one side of the town.

At the best of times, it was a tricky port to enter, requiring an experienced pilot and a careful skipper; in bad weather—or under enemy bombing and shelling—it was a hazardous place to enter with even a moderate-sized ship, and would be made more so by the growing number of half-sunken shipwrecks. Once a ship entered the inner harbor and tied up to a wharf, she was immobilized—as a target for German dive-bombers it was like shooting fish in a barrel. It was easier and quicker to tie up in the outer harbor at the eastern mole, and much faster to get aweigh from there, but the eastern mole was narrow and precarious, almost three-quarters of a mile in length, limiting the flow of men toward the waiting ships. In addition, tides are big in the English Channel—the difference between low and high water can exceed fifteen feet at Dunkirk, which means that access to the ships often involved a long, steep, slippery gangplank, not easy for men who were exhausted and wet, having been under fire for days.

Ramsay learned a lot during the three days before Dynamo, none of it reassuring. The direct distance from Dover to Calais is only twenty-one miles, and the usual way of approaching Dunkirk was to steer directly south toward Calais then turn east for another twenty-five miles, running close inshore along the French coast to avoid the dangerous sandbanks (this was referred to as “Route Z”). With the fall of Calais, however, this course exposed Ramsay’s ships to German artillery fire both coming and going, so he was forced to choose alternate courses. Following “Route Y” vessels sailed from Dover, Ramsgate, or Sheerness northward, clinging to the English shoreline, rounded the notorious Goodwin Sands, on which hundreds of ships large and small had come to grief over the years, turned due east toward Ostend, then southwest along the Belgian coastline to Dunkirk—a loop of some seventy-one miles, which had the further disadvantage of exposing ships to German submarines and E-boats in the North Sea, and of requiring precise navigation to avoid British minefields.

An alternative was “Route X,” which reduced the distance to fifty-five miles, but followed a course that went between sandbanks and through a narrow swept channel in a minefield, and could only be used in daylight. Neither of these courses was difficult for naval ships, but required a degree of precision navigation greater than the average civilian vessel (or amateur sailor) was likely to possess.†

They also required the immediate preparation of a thousand specially prepared charts showing the new courses and, more difficult still, getting one of them into the hands of every captain or yachtsman sailing to Dunkirk, as well as precise sailing instructions from a naval officer. It was no longer possible to simply steer south by the compass until one saw Calais, then turn east along the coast to Dunkirk. Large or small, every vessel would be exposed to all the dangers of the sea, as well as the full fury of the Germans. Even for an island nation that still thought of itself as ruling the waves, this was a challenging undertaking.

A further problem for Ramsay was the state of the troops themselves—as they arrived in Dunkirk, they abandoned their vehicles, blocking streets that were already filled with rubble from constant bombing, and producing chaos. Many of them had lost their officers, and some senior officers had already embarked, leaving behind what was in danger of becoming a disorderly mob. Order would be restored as fighting units began to move into Dunkirk, as a perimeter was set up, and as officers and the Royal Military Police began to separate those who could still fight from those who would be sent to the beaches. In the meantime the most important step Ramsay took was to send Captain W. G. Tennant of the Royal Navy, with a staff of 12 officers and 150 seamen on Monday, May 27, to take up his appointment as senior naval officer Dunkirk. Photographs of Tennant make it clear that he projected an aura of unmistakable command, and he must have been an instantly recognizable figure in his neat blue naval uniform and gold braid among the bedraggled crowd of khaki-clad soldiers. Tennant’s staff, however, apparently decided that he needed some kind of symbol of his authority over the port and beaches of Dunkirk, so they fashioned the letters “S N O” out of silver paper from cigarette and chocolate packets and stuck them to his steel helmet with globs of pea soup.

Captain W. G. Tennant.

This seems to have been unnecessary. Tennant took in the situation immediately, and proceeded to apply his authority as SNO at once. Later he would write,

As regards the bearing and behavior of the troops, British and French, prior to and during the embarkation, it must be recorded that the earlier parties were embarked off the beaches in a condition of complete disorganization. There appeared to be no military officers in charge of the troops. . . . It was soon realized that it was vitally necessary to dispatch naval officers in their unmistakable uniform with armed naval beach parties to take charge of the soldiers on shore immediately prior to embarkation. Great credit is due the naval officers and naval ratings for the restoration of some semblance of order. Later on, when troops of fighting formations reached the beaches, these difficulties disappeared.

This is in sharp contrast to the rosier view of the evacuation from Dunkirk in many histories, but accords with General Montgomery’s opinion later that those who had been evacuated from Dunkirk should not have a special medal or a shoulder flash, since they had been involved in a defeat, not a victory. “I remember,” Montgomery wrote, “the disgust of many like myself when we saw British soldiers walking about in London . . . with a colored embroidered patch on their sleeve with the title ‘Dunkirk.’ They thought they were heroes, and the civilian public thought so too. It was not understood that the British Army had suffered a crushing defeat. . . .”

By Monday, May 27, the bulk of the BEF, a quarter of a million men, and large numbers of the French Army, were all “falling back in hot battle,” desperately fighting for survival against a better-armed and -led army of superior strength. Over the past few days there had been no moment of easy retreat. The only way to keep the BEF together was to fight every inch of the way. If the Germans could have broken through the hard shell of British resistance, the BEF might have been split piecemeal into isolated units, as the French had been after the German crossing of the Meuse. In that case the BEF might have collapsed, the Germans could have broken their way into Dunkirk, the last remaining port, and the entire BEF could then have been rounded up, or defeated as individual units or small groups of men making here and there an isolated last stand wherever the ground and their supply of ammunition made it possible. Nobody had a sense of “the big picture”—each soldier saw only the back of the man in front of him as he marched, or the men on either side of him as he stopped and fought.

Even for those at the top, there was no clear view of events. First of all there were three separate battles taking place, one on land, increasingly savage and bloody, one in the air, difficult to assess, and the last at sea. Then too, even at the very highest level, there was a certain degree of confusion and reluctance to face the facts. The British had only a vague idea of what the French were doing, or what they might still be capable of doing, still less of what the Belgians were doing, even though the Belgian Army was on the left flank of the BEF as it retreated. The fighting troops were exhausted, outnumbered, had been without rations for days, had been fiercely engaged with the enemy for nearly two weeks, and been bombed day and night. They were held together by those two old-fashioned, but vital, elements—discipline and loyalty to their own regiment, as has been the case since the mid-seventeenth century.

Celebration of the evacuation and immortalization of “the little ships” have tended to draw attention away from the savage fighting that preceded it. Hugh Sebag-Montefiore, in his magisterial account on the campaign, estimates that of the approximately 2,500 men in one brigade (his chosen example is 4 Brigade of 2nd Division of III Corps, consisting of 1st Battalion the Royal Scots, 2nd Battalion the Royal Norfolk Regiment, 1st/8th Battalion the Lancashire Fusiliers) only 650 made it back to England, which means that three-quarters of the brigade was killed, seriously wounded, or captured between May 10 and June 1, 1940—and there is no reason to suppose that 4 Brigade was unusual. This is a rate of loss comparable to that in the bloodiest battles of the First World War, or the American Civil War, and an indication of just how hard the fighting was during the retreat of the BEF to Dunkirk.

Although the German panzer divisions remained a major concern, the countryside between Lille and Dunkirk lent itself to the bitterest and most old-fashioned infantry warfare. The flat ground was intersected by a complex web of big and small rivers, canals, and ditches, and each bridge had to be fought over—or destroyed before the enemy could get to it. It was also a mass of small villages and farms, in which most of the buildings were solidly built out of local stone, ideal for mounting a defense, in a battle much of which was being fought at close range by rifle fire, machine-gun fire, grenades, and even the bayonet and the pistol, as well as by artillery and more modern weapons like tanks.

Accounts of it read like those of the fighting in the First World War. “They were closing in on all sides, mopping pockets up,” one soldier recalled.

The [German] infantry was bunched up behind the tanks. Following behind in bunches, using the shelter of the tank. . . . I found myself with a group of others being driven back towards the canal. I actually fired the Boys anti-tank rifle for the first time. It was a terrifying weapon. To even fire it, you had to hang on to it like grim death, because it would dislocate your shoulder if you didn’t. I fired at a tank coming over the main bridge about 50 yards away, and I couldn’t miss. It hit the tank—and knocked the paintwork off. That’s all it done. It just bounced off, making a noise like a ping-pong ball. After that, an officer said, “Leave that blasted thing there, Doe, and get the hell out of it!”

The same soldier, Lance-Corporal Doe, also recalled looking down at a dead German and envying his superior equipment: “He had his jackboots on, a belt round his uniform, a canister at the side, but he wasn’t lumbered down. He wasn’t tied down with packs and equipment like we were. . . . We were not only outnumbered . . . but out-armed in every way.”

One soldier remembered passing over the body of a British soldier cut in half by shell fire, the two halves connected only by the intestines; another, of the 9th Battalion, Durham Light Infantry, remembered trying to lift the body of a dead British soldier and finding that “when we lifted the top part of him, the bottom part stayed where it was. It was only the buttons on his battledress and his pants that were keeping his body together. . . . We took him and did with him what we did with all the others: we dug a hole in someone’s garden and tipped them all in.” The surprising thing is the toughness of these soldiers, many of whom were half-trained part-timers rather than hardened regulars.

The German superiority in armor was still important, particularly since the BEF had lost most of its much-smaller armored force defending Arras on May 21, but British infantry could still hold its own, and the Germans had to fight hard for every gain they made. Every war produces losses and casualties of course, but the German infantry had had a fairly easy time of it to this point. Once Army Group A had crossed the Meuse and broken through the ineffective French defenses, German losses were low, and the same was true for Army Group B, given the collapse of the Dutch Army and the rapid demoralization of the Belgian Army. By now the Germans were coming up against the hard core of British regular and Territorial infantry battalions, and they bitterly resented it.

May 27 was therefore marked by a serious incident that was to become all too familiar. The 3rd SS Division Totenkopf, originally formed from concentration camp guards, was part of the reserve of Army Group A and had already acquired an unsavory reputation in the ten days it had been fighting—among other things the division had refused to accept the surrender of French Moroccan troops and executed them out of hand instead, an example of orthodox Nazi racial fanaticism in the field that caused some senior German Army officers to raise a well-bred eyebrow. SS Totenkopf suffered from that familiar German combination of racial superiority coupled with a corrosive inferiority complex. They thought themselves superior to the rest of the German Army, but at the same time they knew they were looked down on as amateur soldiers and party hacks by many senior officers. They not only had a chip on their shoulder; they took heavier losses than were necessary, and were indecently quick to shoot civilians who got in their way or showed any degree of resentment.

The division’s commander, SS Obergruppenführer Theodor Eicke, was a major figure in the SS, one of the creators of the Nazi concentration camp system and the infamous inspector of concentration camps, as well as the man who had executed the thuggish leader of the Nazi Brownshirts Ernst Röhm in his cell during “the Night of the Long Knives” in 1934, which among other things ensured the supremacy of the SS once and for all over the rest of the Nazi Party.

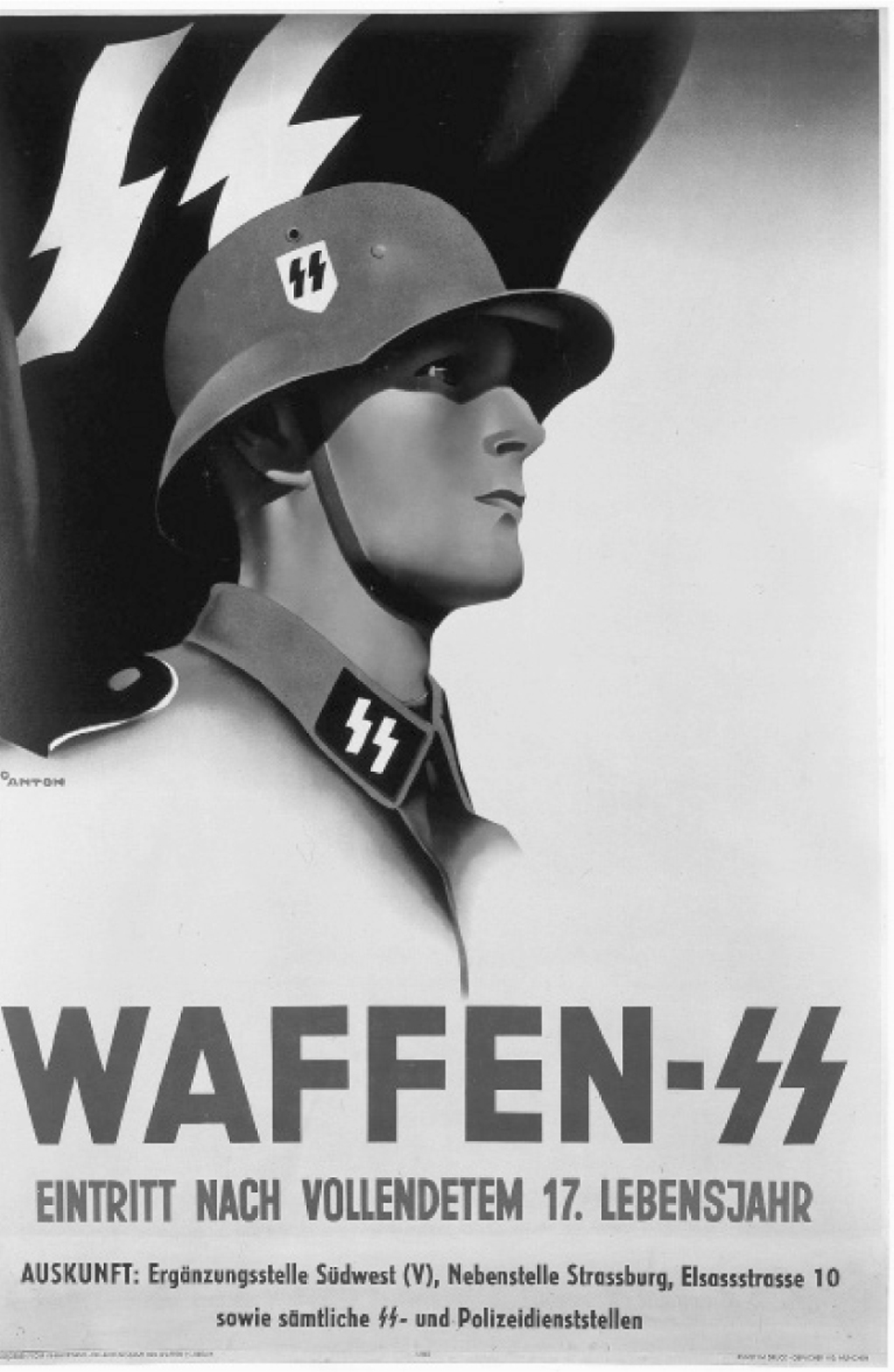

Even in the Waffen SS, Eicke stood out for his brutality, and much to the German Army’s dislike he and his troops thought of themselves as an elite force, entitled to despise and ignore the ordinary rules of war. They therefore felt particularly humiliated when they were beaten back and forced to retreat after the British counterattack at Arras on May 21, and suffered casualties during the following days that they regarded as excessive.

Thus they were in no mood for chivalrous behavior on the morning of May 27 when they came up against a British force consisting of companies from the 2nd Royal Norfolk Regiment, the 8th Lancashire Fusiliers, and the 1st Battalion, Royal Scots. The British, though badly outnumbered, fought hard—SS Totenkopf lost 4 officers and 150 men killed, and nearly 500 wounded—but they were eventually split up and cut off. Two companies of the Royal Norfolks dug in around a solid, ugly, two-story brick farmhouse near the unfortunately named village of Le Paradis, which they defended fiercely from before noon until after five in the afternoon, at which point they ran out of ammunition. They had been forced to abandon the farmhouse for a cow barn after the Germans brought up tanks and artillery to destroy it and what remained of the two companies, most of whom were wounded, came out with their hands up, and surrendered under a white flag once they could no longer fight.

The SS Totenkopf quickly demonstrated their contempt for the normal rules of warfare. The ninety-nine men were marched into a barn courtyard and machine-gunned. Any who showed signs of life were finished off with a pistol shot to the head or clubbed to death with a rifle butt, except for two men who although wounded miraculously survived under the pile of bodies, escaped during the night, and hid themselves in a pig sty, where they were discovered and cared for at great risk by a French farm family. They were finally captured by German Army soldiers and sent to a POW camp.

The SS officer who ordered the massacre, SS Hauptsturmführer Fritz Knöchlein, had already murdered about twenty men of the 1st Royal Scots that day, and hidden their bodies in a mass grave. At his trial after the war Knöchlein claimed that the Royal Norfolks had been using expanding or “Dum-Dum bullets,” which are outlawed by the Hague Convention of 1899 and 1907, but that seems unlikely since all British small arms ammunition used in the Second World War was of the normal military full metal jacket pattern.‡

On Tuesday, May 28, the next day, the 1st SS Division Leibstandarte Adolf Hitler, commanded by an even more notorious Nazi, Hitler’s former chauffeur, bodyguard, and backstreet brawler SS Obergruppenführer Sepp Dietrich, massacred eighty officers and men of the 2nd Royal Warwickshire Regiment, the 4th Cheshire Regiment, the Royal Artillery, and some French soldiers, at Wormhoudt after they had run out of ammunition and surrendered. Dietrich, who would rise to become the SS equivalent of a colonel general, was on close terms with the Führer, perhaps the only man who was permitted to refer to him, and even address him as “Adi,” an affectionate diminutive of Adolf. He had made his name in the barroom fights and street violence that accompanied the Nazi Party’s rise to power. He was not the man to restrain his officers and men from executing prisoners, and in fact men under his command would do so again in January 1945 when they murdered eighty-four Americans who had surrendered at Malmedy, Belgium, during the Battle of the Bulge, after four years of unrestrained war crimes on the eastern front.

Complaints about the massacres made their way up through the German Army chain of command at a leisurely pace, but when it came to discipline the Waffen SS reported to Himmler, not the OKH, and in any case Eicke and Dietrich were almost untouchable, so the two “incidents” were allowed to vanish into the vast paperwork of the German Army.

Even such imposing figures as Colonel General von Rundstedt knew when it was necessary to turn a blind eye.

_________________________

* Two hundred forty-three ships and boats are listed as having been sunk by German mines, torpedoes, gunfire, or bombing, but the actual number is probably far higher since many sinkings of private vessels went unrecorded. When a ship went down, the soldiers on board often went with her if they were below deck. When the destroyer HMS Wakeful was torpedoed, she took six hundred soldiers down with her, for instance.

† The new German magnetic mines posed an additional problem for Ramsay. Naval ships were equipped with a new and secret “degaussing” coil, which prevented the mine from being detonated by the ship’s magnetic field, but there was no time to degauss every civilian vessel, and mines were to cause many of the sinkings during the Dunkirk evacuation. Ramsay set up five degaussing stations, but the crews of many of the smaller civilian vessels didn’t know about them.

‡ Knöchlein was found guilty and hanged in 1949.