Home again!

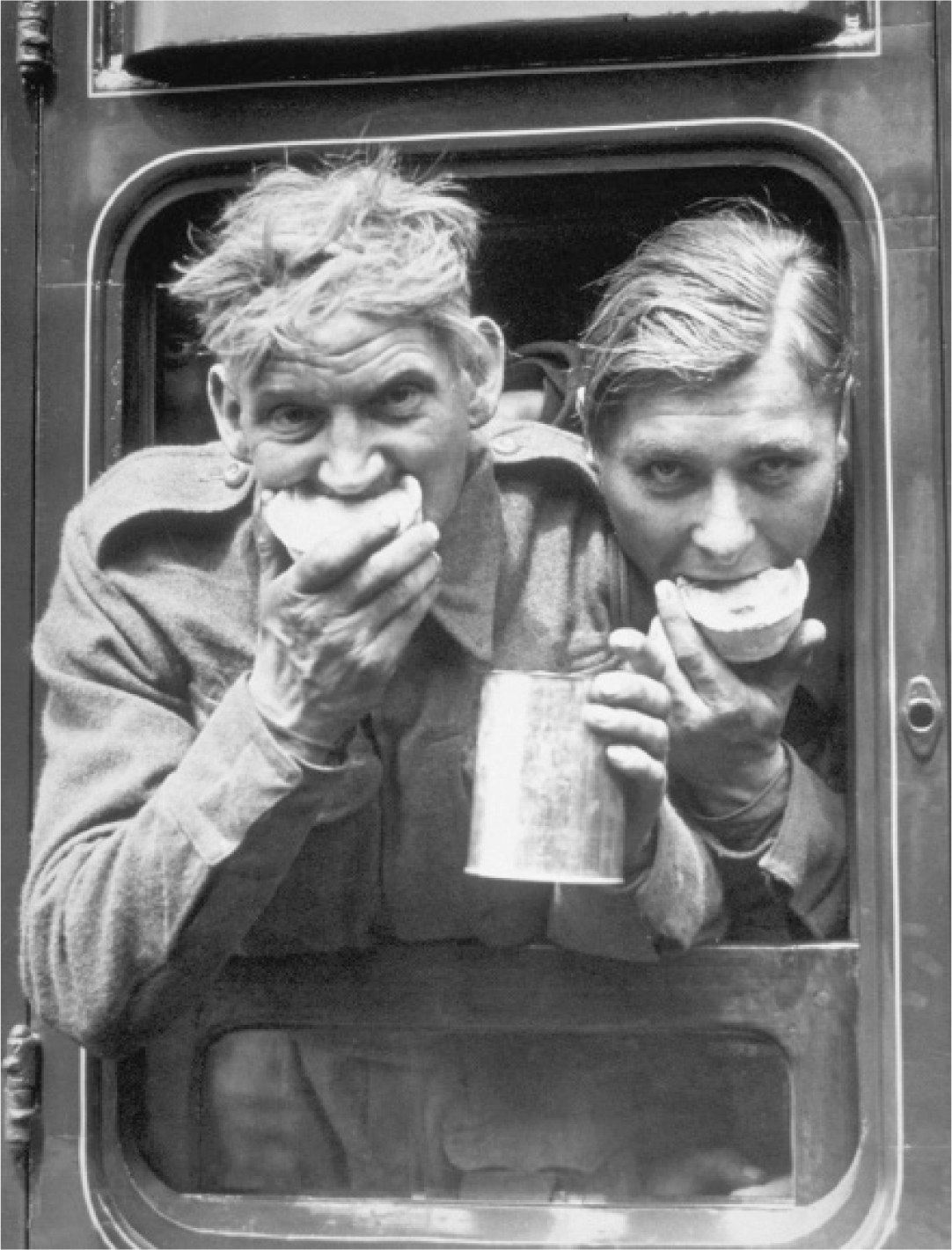

“The Best Mug of Tea I Have Ever Had in My Life”

Home again!

BY THURSDAY, May 30, it was clear enough to everybody that the BEF was struggling to get home and that the German hold on Dunkirk was tightening with every hour. There was, of course, no equivalent to people crowded around a television set, as they would be today, watching events as they took place in a kind of national communion, nor of “embedded” correspondents reporting independently on what was happening in “real time.” News was carefully filtered and released a day later, much of it still untrue, or at least tidied up.

German losses were wildly exaggerated, and many tales were told of the Germans’ marching like obedient automatons into withering fire, and of scores of German aircraft being shot down by a handful of British fighter planes. The official French communiqué of the day was even more divorced from reality: “The French and British troops that are fighting in Northern France are maintaining with a heroism worthy of their traditions a struggle of exceptional intensity. . . . The French Navy, in defending their ports and lines of communication, is lending them powerful support. Under the command of Admiral Abrial, with a very large number of ships, it is engaged in supplying the fortified camp of Dunkirk. . . .”

In fact, the doughty Admiral Nord, Vice-Admiral Jean-Marie Abrial, commander of French naval forces in the north, was in a state of barely concealed fury at the British. Sequestered at his fortified headquarters in Bastion 32 of the old Dunkirk fortifications (which had been built to protect Dunkirk from the British), Abrial had not been informed of the British decision to evacuate the fighting troops of the BEF, not just “the tail.” His intention was to defend the town of Dunkirk “to the last man,” and his attitude toward the British was one of bristling hostility at their departure, only barely concealed by ironic Gallic politeness. Not surprisingly he would go on to become a major figure in the collaborationist government of Marshal Pétain.

Perhaps because of Abrial’s attitude toward the British, there was almost no communication between General Lord Gort at La Panne and Admiral Abrial in Dunkirk, a distance of about ten miles, as if they were fighting two entirely separate battles. Lord Gort disliked scenes and arguments with the French, and was certain to get both at Bastion 32. Abrial and his staff had been outraged by British demands to demolish the bridges over the canals in Dunkirk, and seem to have ignored the vast fleet of naval vessels and small boats gathering off Dunkirk, even though the mole and the beach to the east of Dunkirk were perfectly visible from Bastion 32, had he chosen to come out of it.

Gort’s irascible chief of staff, Lieutenant-General Pownall, to whom Gort delegated a good deal of the irritating business of talking common sense to the French, expressed his feelings vehemently in his diary: “I suppose they [the French commanders] think we are tiresome, pig-headed people, but their slackness, lack of self-discipline, and ‘temperament’ is, to us, just appalling and we can’t compete.” Pownall was particularly incensed by the French taste for grandiose patriotic rhetoric, unaccompanied by any realistic plan. “The Admiral’s boast that he would hold on till kingdom come was nonsense. The French formations there . . . are quite useless. Any holding that may be done will be done by us.” Admiral Abrial would later sum up his own opinion of British behavior at Dunkirk with his own, eloquently expressed bias: “The British never took part in the struggle as faithful and loyal fighting comrades—but only, and on occasion not without bravery, for their own personal ends . . . the evacuation of British personnel.”

The British government had already expressed its intention to evacuate as much of the BEF as it could, together with what remained of the French First Army, but either this message did not reach the French commanders on the spot, or they simply did not wish to hear it and were in any case determined to pin as much of the blame for a military disaster as they could on the British.

Needless to say, none of this was reflected in the newspapers. At Well Walk in Hampstead my mother, who like many middle-class English children had been educated at a French convent school despite being Protestant—she had taught me the multiplication table in French to the tune of “La Marseillaise” repeated over and over again—retained a firm belief in the greatness of the French Army. They had stopped the Germans at the Marne in 1914, they would stop them now on the Seine, if not before, and her confidence in General Weygand was unshaken. This was common throughout Britain, and rose right to the top, since Winston Churchill, who by now should have known better, still had faith in the French genius for warfare. Churchill’s confidence in his old friend and luncheon companion General Georges was slightly shaken, but he still believed that the Napoleonic touch would soon appear, although those few who were permitted to approach General Weygand, the Allied commander in chief, whose routine of quiet mealtimes without any military “shop talk,” followed by a healthy stroll on the gravel paths outside his office after lunch and dinner, saw no trace of it appearing as yet. Only those who were in direct contact with the French Army doubted its ability to recover. My father retained from his service in the Austro-Hungarian Army a profound lack of respect for the generals of every army, and complete lack of confidence in the truth of any military communiqué.*

Whatever confidence the prime minister had in the French Army was surely somewhat shaken by the arrival in London of Lieutenant-General Pownall, accompanied by Captain the Earl of Munster, Lord Gort’s aide-de-camp, via a “Thames tripper steamer” to Margate under “heavy air attack.” Pownall was not the man to sugarcoat the situation or to be overawed even by the prime minister. A more timid soul than Pownall might have felt that he was like a prisoner in the dock called before a meeting with Churchill in the center chair like a judge, attended by the service ministers and the chiefs of staff, like a jury. Pownall declined to be “pinned down” about casualties, and when told by the prime minister of “the importance of embarking French as well as English,” he replied that if “the French did not produce resources of their own for embarkation this meant that every Frenchman embarked meant one more Englishman lost.”

Pownall noted in his diary, with some satisfaction, that this was “an inconvenient truth which he [Churchill] did not gladly hear,” and congratulated himself on putting it to Churchill “straight enough.” It is worth noting that telling Churchill what he didn’t want to hear was not necessarily a good personal strategy. Despite his widely acknowledged competence Pownall was never advanced to a higher rank for the rest of his career—he seems to have lacked the right personality to “click” with that of the prime minister. Interesting as Pownall’s diaries are, they do not show any evidence of charm, tact, or a sense of humor, still less of the ability to hold his tongue in the face of wrath, some or all of which were necessary to deal with Churchill. Pownall emphasized the need for more small boats—he had seen for himself how exhausted the rowers were as he was taken out from the beach to the Royal Eagle—and reported frankly on the difficulties between the British and Admiral Abrial. During the discussion on this subject, it became clear that there was in fact no common policy on evacuation between the French and the British governments, which does much to explain Abrial’s hostility.

Thames pleasure steamer heading for Dunkirk.

Pownall managed to convince everybody at last of the importance of taking off the fighting elements of the BEF, instead of just the “tail,” and above all confronted Churchill with the need to provide Lord Gort with a specific order about when to come home, since otherwise he would certainly choose to remain with his men. After the meeting Pownall went to Buckingham Palace to tell his story to the king, then back to the War Office, where he seems to have been the first to point out that while the RAF had been “working all out,” those standing on the beach at Dunkirk had not seen the airmen and were complaining so bitterly that soldiers sometimes refused to let airmen into the boats.

Whatever else Pownall’s visit did, it prompted Churchill to follow his first instinct and give Lord Gort a firm order. “Report every three hours through La Panne. If we can still communicate we shall give you an order to return to England with such Officers as you may choose at the moment when we deem your Command so reduced that it can be handed over to a Corps Commander. You should now nominate this Commander. . . . This is in accordance with correct military procedure, and no personal discretion is left to you in the matter. . . . The Cabinet have approved this telegram.” If one of the marks of leadership is to write or dictate a clear order, Churchill certainly had this most precious ability. There is not the slightest ambiguity in his message to Gort—although Churchill never rose above the rank of lieutenant in the British Army, it could have been written by Wellington or Grant.

He was less successful at dealing with the French, who were still pleading for more British fighter planes and infantry divisions. In contrast to his resounding communiqués, General Weygand had told Major-General Spears, Churchill’s personal representative to Premier Reynaud, “Nous sommes à la limite.” The fate of the northern armies, including the BEF, was no longer the first concern of the French—they now faced an enemy that was vastly superior in numbers, and had shown itself to be superior in equipment, fighting techniques, and, perhaps most important of all, fighting spirit along the line of the Somme, the Aisne, and the Maginot Line, a front almost five hundred miles long from the sea to the Swiss border. Although Premier Reynaud was far from communicating his thoughts to his British ally, he was already considering the possibility of forming a “national redoubt” in Brittany and of sending half a million men of military age to North Africa for training. The question was no longer whether the north could be held—it was already lost—but whether, once the Germans had recovered their second wind, Paris could be held.

For those approaching Dunkirk, these larger issues were not a concern. Despite the confusion, the chaos, and the bloodshed on the beach, many of the British derived a strong sense of comfort from their first sight of the sea. From here it was only thirty miles to England, and for an island race the sea appears as a friend, not an enemy. Unfortunately, there was still a serious lack of organization on the beach—General Gort and his staff considered it to be their job to get the BEF to the beach, after which the navy would take over; the navy considered its job to be taking the troops home, so nobody had given much thought to organizing the efficient evacuation of some 400,000 men. The process of improvising on the spot an evacuation of this size was necessarily makeshift, rough-and-ready, and on occasion brutal, particularly since the days and nights of retreat and the separation of many men from their own unit, with its familiar faces, its officers and NCOs, and its esprit de corps, led to a certain decline in discipline. Some officers used their rank to get into the boats first, and in the circumstances cohesion and respect for rank and orders tend to deteriorate rapidly, replaced by the spirit of sauve qui peut, every man for himself.

This was much less true of the evacuation from the eastern mole, which was only five feet wide and nearly a mile long and on which Captain Tennant’s men could maintain order more firmly, but on the miles of open beach the troops tended to form up in untidy lines themselves, until they reached the water. This was in part because the habit of queuing in an orderly way was a well-known national obsession. The queues were sometimes broken when German fighter aircraft flew low and machine-gunned the beach, or when German bombers and dive-bombers dropped bombs, but as soon as they were gone the lines reformed and most men retuned to their original place, except for the dead who were quickly buried in the sand, and those badly wounded who needed to be carried to the nearest medical post. Stretchers were in short supply, as well as the men to carry them, and only the fittest could wade out to the boats, sometimes chest or neck deep in rolling surf, and then try and climb into a rolling, overloaded small boat. The seriously wounded who could be moved were mostly evacuated from the eastern mole by stretcher onto small passenger liners converted into hospital ships. First impressions of the beach were almost always misleading. Bombs and canon shells were less dangerous than the Germans (or the troops on the beach) expected—the sand tended to bury a bomb or a shell before it exploded, muffling the effect and preventing the spray of hot metal splinters that were the most dangerous side effects of an explosion, unless of course you were unlucky enough to receive a direct hit. On the other hand, “strafing” by low-flying fighter planes caused many more casualties where men were standing in line or bunched up—small-caliber machine-gun fire was deadly.

Captain Henry de La Falaise, the French liaison officer to the 12th Lancers, arrived on the beach midmorning on May 30, after the regiment had abandoned and destroyed their remaining armored cars. Trying to cross the bridge leading to La Panne, he encountered a momentary difficulty: British officers and military policemen were preventing French troops from crossing the bridge, and it was only after his commanding officer and his troop commander linked their arms through his and insisted he was part of their regiment that he was allowed to proceed. French troops were being sent farther west along the beach to the small resort towns of Bray-Dunes and Malo-les-Bains, where for the time being they were not being removed by boat. It was “a good two mile walk before reaching La Panne,” writes La Falaise, “which, we can see, and hear, is being blasted by artillery fire as well as bombed from the air. It [the road] is jammed with abandoned trucks which are being emptied of their contents by hundreds of stragglers in French uniform who are camped gypsy-fashion around fires in the neighboring dunes. Some of them are drunk.”

At first La Falaise was embarrassed by this lack of discipline among his countrymen, until he realized that these were older men from the reserves who were not going to be evacuated by the British and knew they were going to be facing German captivity. It was now he who was embarrassed as they watched him enviously, marching down the road with the British to what they regarded as safety. La Falaise went through the ruins of La Panne, in peacetime a pleasant little beach resort, and at the end of a narrow street, “we smell the tang of a salty breeze and a few minutes later, beyond a narrow stretch of yellow sand . . . the glorious sight of the splashing surf and beyond, stretching to the end of the horizon, the dark green waves over which we may be borne to England. . . .”

This was a common reaction to the sight, but actually getting to England was, for La Falaise like thousands of others, a long, dangerous, and exhausting experience. He describes how tarpaulins were laid down on the beach under constant artillery fire allowing vehicles to be driven over the sand at low tide to form a makeshift jetty, but by midafternoon there were still no boats in sight, and the destroyers were several miles out to sea, exchanging shellfire with German artillery, which was now less than four miles away from La Panne. Tons of explosives came roaring over the beach in both directions, shells occasionally falling short and landing in the sand or the shallow water. In the afternoon a full-scale German bombing raid rained bombs down on La Panne. “The noise and the commotion,” La Falaise writes, “are so great that I feel my legs shaking under me and my heart pounding in my chest.” It was not until the early evening that the destroyers moved inshore and began to take off soldiers in their own boats, but they were quickly filled, and La Falaise ended the day still on the beach drinking that traditional English restorative in difficult situations—a hot mug of tea.

One problem that affected the embarkation was the lack of any effective communication between the ships and the beach, or of any reliable direct communication between Dunkirk and Dover. Few wireless sets had survived the rigors of the long retreat, and as rear-echelon troops were evacuated before the “fighting” troops, the number of signalers was quickly reduced—even at the best of times radio equipment was not the strong point of the British Army in 1940 in contrast to the Germans. The day before there had been a costly error when Admiral Ramsay received a message from BEF headquarters in La Panne—transmitted from there to the War Office and then on to the Admiralty until it finally reached Ramsay in Dover—mistakenly warning that Dunkirk harbor “had been blocked by damaged ships.” Another roundabout wireless message from Captain Tennant was mistakenly decoded as meaning that it was now “impossible . . . to embark more troops” from the harbor. Losses among the destroyers prompted the Admiralty to withdraw the more modern ones from Ramsay, leaving him with only fifteen older ones, most of them World War One veterans. All this probably explains the confusion and the absence of boats in some places on May 30, which La Falaise and others commented on. The result was that more men were embarked from the beach than from the harbor, the only day of the evacuation of which this was true, and that the total for the day was 53,823, well short of what Ramsay had hoped for.

* * *

Even for those who succeeded in getting away it was not an easy day. Fred Clapham, of the Durham Light Infantry, recorded his experience, which was typical:

We went down to the beach again and could see a couple of lines of men standing from the beach out into the sea, with the most seaward men up to their necks in water. Enquiring, we were told that they were waiting their turn for a boat to pick them up and take them out to a ship, and we had better get to the end of the queue. Can you imagine standing in single file, in water, being periodically shelled and machine-gunned, and waiting for a boat!? . . .

Along the water’s edge there was a continuous line of flotsam and rubbish washed ashore from the sunken ships. Bits of boat, lifebelts, broken tables, chairs, tins, cans, etc etc. We came across two halves of a canoe, and would you imagine it still had two perfectly good paddles floating alongside it. Nearby was also a floating ship’s raft. So we took off all our heavy gear, rifles, packs, ammunition, tin hats, boots and piled them in the centre of the raft which was about 5 feet long by 3 feet wide, and took a paddle each and pulled off to sea in the direction of the nearest ship.

Unfortunately, the swell tipped over Private Clapham’s raft, and he and his “mate” had to swim back to shore, soaked and coated with diesel oil. There they waited until a naval boat rowed in to the beach, at which point a sailor told him to go around to the bow of the boat and hold it steady while other men boarded it, which he did, with the oily water occasionally breaking over his head. When the sailors began to row the boat away from the beach, Clapham shouted out, “Hey! what about me?” The boat paused long enough for one of the crew to haul him on board, then they rowed out to where its parent ship waited, the minesweeper Albury, and Clapham was given “the best mug of tea I have ever had in my life. Real navy stuff. Hot, strong, sweet and with a generous ration of rum to boot.” He was allowed to strip off his uniform and dry it in the engine room, and “was in uniform when we landed at Margate to a hero’s welcome.” Of his battalion of 800 men only 250 eventually returned to England. He was a lucky man.

All war is luck and chance of course, but the evacuation of the BEF was something more like a lottery on a large scale. Some people went to the beach, fell into the right line, were taken aboard a ship with a minimum of drama, and disembarked a few hours later at Dover; others waited for hours or days on the beach, or in the reeking ruins of Dunkirk, waded out to sea, and were nearly drowned before reaching a ship, only to have it sunk from under them by a mine, a torpedo, or a bomb. Some were maimed or killed on the beach—and not a few on the narrow eastern mole, which was exposed to constant shelling and bombing—others merely spent a few hours of grim, dismal waiting, punctuated by moments of terror and surrounded by sights of the wounded and dead from which it was impossible to avert one’s eyes.

A lot of men made the crossing packed shoulder to shoulder on deck and exposed to machine-gunning by German aircraft, while others crowded below decks in foul-smelling darkness on board a fishing trawler. Some of the Channel Island and Isle of Man passenger liners and ferries had been pressed into service with their peacetime routines still miraculously intact. One soaked, exhausted, and thirsty officer was met by a steward in a white jacket, asked him for a beer, and was told very politely that he could not be served it until the ship was beyond the three-mile limit; another was taken to the first-class salon, to the tinkle of bells and silverware, and served tea on a silver tray, along with a plate of tea sandwiches neatly arranged on a starched napkin with the bread crusts carefully cut off.

Despite the relatively small number of French personnel taken off in the first few days, it is often possible to see French officers and soldiers mixed in with the British in photographs of the ships as they docked in England, and in one case a French nurse in an elegant cape, carrying a leather satchel slung over one shoulder that looks as if it had been bought on the rue du Faubourg Saint-Honoré in Paris. Luck had everything to do with it—the military police tried to stop vehicles approaching the beach, but French drivers ignored them and careened onto the beach or into the streets of Dunkirk; sergeants and Captain Tennant’s men tried to assemble people in neat lines, according to their own view of priorities, but some made their own way onto boats anyway.

Brian Bishop, a soldier, was “roped in by a naval officer to help carry wounded on stretchers alongside the mole to the ships tied alongside. The mole had been bombed in several places and across the gaps gangplanks had been placed. It was difficult carrying stretchers along it and then having to lift them shoulder height across the gangplanks. . . .” Bishop and his fellow soldiers were strafed—there was no protection on the mole and nowhere to take cover, so they were open targets. At one point, an officer examined his stretcher case and said briskly, “He’s dead, tip him out and fetch another.” Late in the afternoon a naval officer helped him load a stretcher case onto the paddle-wheel pleasure steamer Medway Queen,† formerly of the New Medway Steam Packet Company, Rochester, Kent, and in a moment of unexpected kindness suddenly said, “Jump aboard, this is your last chance.” Although the ship was bombed and machine-gunned on the way home (“it was standing room only and no life-jackets,” wrote another passenger on her, Dick Cobley), Bishop was landed in Dover at midnight, and greeted by a young girl holding a tray of sandwiches. In an age when almost everyone smoked, the one thing most of the troops remember is being able to pick up hundreds of packets of cigarettes from NAAFI stores littered on the beach and in the streets of Dunkirk.

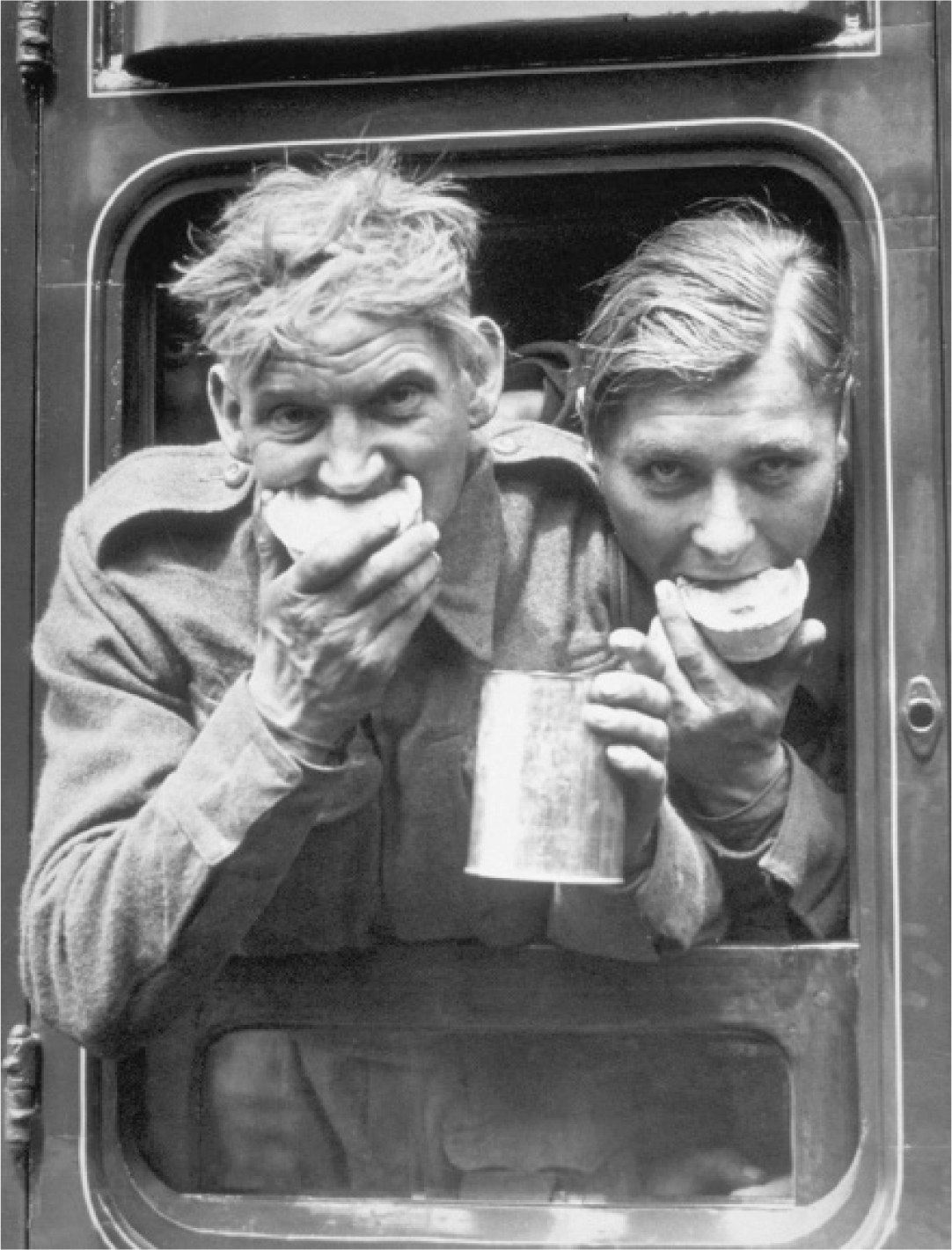

Waiting at home for the troops to return—the “NAAFI girls” with tea.

Tales of NCOs and officers maintaining discipline and order at gunpoint are common among survivors, and no doubt they did, but it is worth noting that many of the troops were still armed—those who lost their weapon mostly did so in the surf as they tried to board a boat, or were ordered to chuck it into the sea as they boarded a ship—and that threatening a bunch of armed men with a pistol is a risky thing to do. Tales of men being shot because they broke into a queue or tried to force their way on board a ship are rife but must be taken with a grain of salt, and there is no mention of summary executions in the casualty lists, perhaps not surprisingly. A certain number of men lost their nerve under the constant bombing and shelling—it was called “shell shock” in the previous war—but for the most part those in charge seem to have tried to find a place for them, and their fellow soldiers seem to have been sympathetic, rather than judgmental.

* * *

Winston Churchill reviewed the evacuation that evening with the service ministers and the chiefs of staff. “860 vessels of all kinds were at work,” he reported, from yachts, lifeboats and fishing vessels to destroyers, passenger liners, and ferries. The total number of troops brought off had by then reached about 120,000, of whom only 6,000 were French—a matter of deep concern to the prime minister, who had made plans to fly to Paris the next day for a meeting of the Supreme War Council, accompanied by the lord privy seal, Clement Attlee, the leader of the Labour Party, and the chief of the Imperial General Staff, General Sir John Dill.

There were sure to be French complaints about this.

_________________________

* An exception to this was General Édouard (“Eddie”) Corniglion-Molinier, film producer, bon vivant, pioneer aviator, war hero, member of the French Resistance, and eventually prominent Gaullist political figure, who played much the same role for the Korda family in France since the 1930s that Brendan Bracken did in Britain.

† Medway Queen eventually took off more than seven thousand men in seven trips, became known as “the Heroine of Dunkirk,” and is now restored and preserved, moored at Gillingham Pier, on the river Medway.