Back to Blighty! (Note gas masks.)

Back to Blighty! (Note gas masks.)

SATURDAY, JUNE 1, did not signify the end of Britain’s disagreements with France, but the relative success of the evacuation to that date did at least bring to an end the prime minister’s reluctance to deal with pro-peace arguments from within the War Cabinet. He had been reluctant to release the French to seek out German peace terms, and more reluctant still to join them, but felt he could push Lord Halifax only so far. Now almost half of the fighting strength of the BEF was back in England, over three times the number that even the optimists had predicted a few days ago—admittedly without its equipment, its artillery, in many cases even its rifles and boots, but the men could be rearmed. Churchill’s nimble mind was already turning toward the hundreds of thousands of rifles France had ordered from the United States but which had not yet been shipped, and which he could divert to Britain. The United States still had hundreds of thousands of brand-new rifles in storage from World War One, and in those days the government armories and the arms manufacturers of Massachusetts and Connecticut set standards in the mass production of weapons that were the envy of the world. Arms could be provided—the important thing was that the trained regulars, commissioned and noncommissioned, those indispensable professionals without whom the army could not be rebuilt, were coming home or already there. The sense of dread was giving way not to optimism but to a glimmer of confidence in the island’s power to resist what would have to be, after all, a hastily German improvised invasion.

Early in the morning of June 1 the prime minister replied to two of the many notes and papers on his bedside table with the firmness that would henceforth be his hallmark. To a suggestion from the Foreign Office (always foremost among government departments in pessimism under Halifax) that if worse came to worst the prime minister should consider making “the most secret plans” to evacuate the royal family to some part of the British Empire, together with the crown jewels and the coronation chair, Churchill replied bluntly, “I believe we shall make them rue the day they try to invade our island. No such discussion can be permitted.”

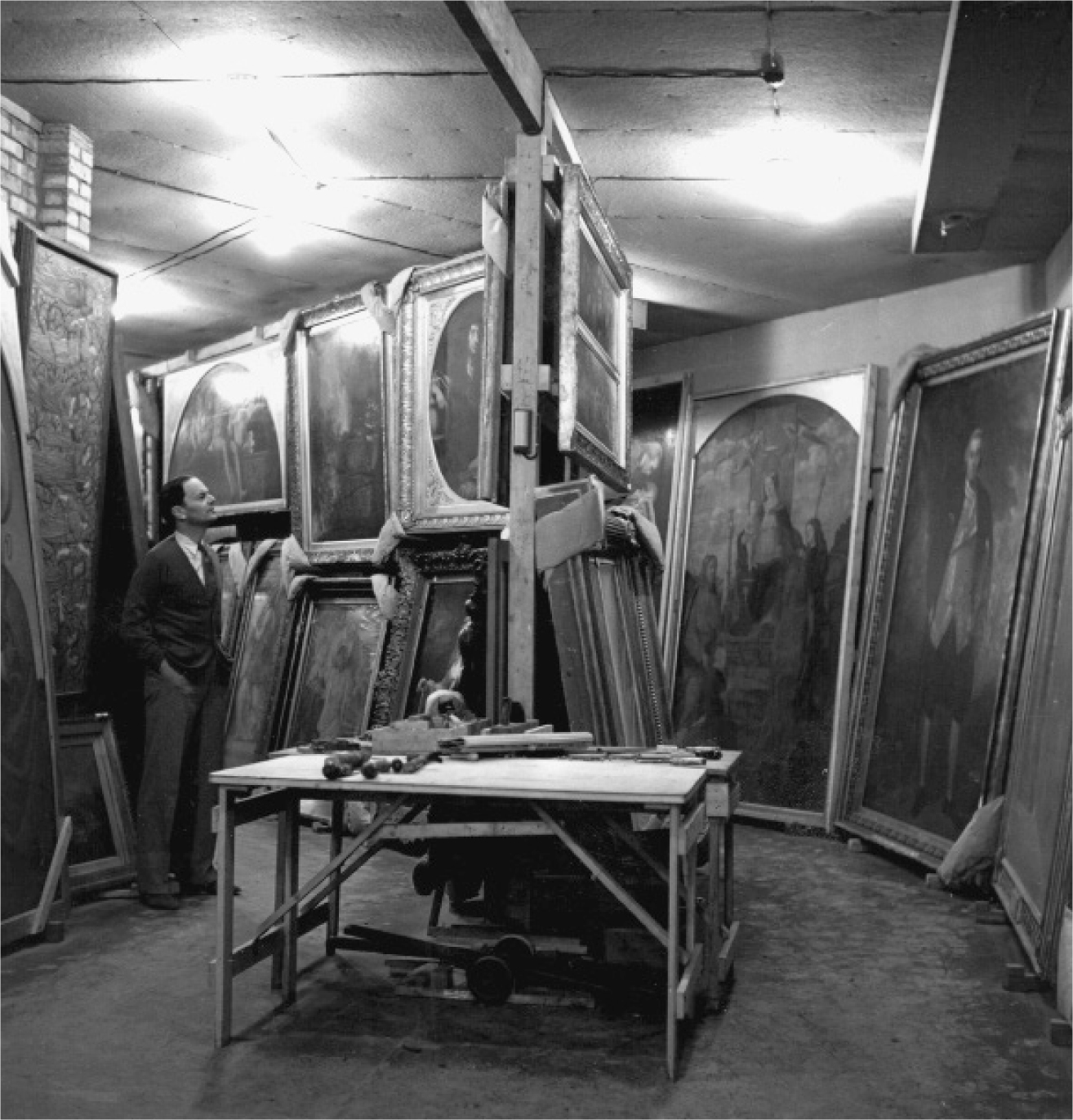

There was no hint of shilly-shallying about his words, still less for the director of the National Gallery, Kenneth Clark, the future life peer and television documentary star of Civilization, who had proposed to send the masterpieces of the collection to “a safe haven” in Canada for the duration: “No. Bury them in caves and cellars. None must go. We are going to beat them.”

Kenneth Clark surveys the masterpieces of the National Gallery removed for safekeeping.

From the port and beach of Dunkirk that would have seemed an unlikely proposition. Dunkirk was now besieged, and the Germans were nibbling away at the slender stretch of beach the British still held. To those trapped there under the pall of oily smoke, exposed to constant shelling and attacks from the air, it presented the nightmare picture of a defeated army, in no position to “beat” anyone. Major-General Alexander, now in command of what remained of the BEF, about twenty thousand troops, made his way to Admiral Abrial’s headquarters early in the morning for yet another baffling and fruitless conversation. Nothing illustrates better the confusion of French strategy and politics than Abrial’s position at Dunkirk. The French had placed a senior naval officer in command at each of the major ports. With perfect Cartesian logic as the French First Army and the BEF retreated to Dunkirk, they therefore came under the command of Admiral Abrial, at least in his own mind. This resulted in a land battle commanded by an admiral. It has to be said in Abrial’s favor that he was made of sterner stuff than most of the French generals in and around Dunkirk, but as an admiral who never came out of his bastion in Dunkirk harbor, he was not in a position to lead a land battle, nor did he attempt to communicate with the commander of the BEF, which would soon be forced to evacuate La Panne, and with it the last direct telephone line to London.

One result was that General Alexander had no idea that there were still nearly seventy thousand French troops in and around Dunkirk with more arriving every day, some of whom (but by no means all) were fighting hard to hold back the Germans, while Abrial was unaware of the heavy losses the British had already sustained in naval and commercial shipping, not to speak of smaller vessels and boats. The meeting between Abrial and Alexander on June 1 was therefore like a dialogue of the deaf, made even more difficult by the gaping differences between them. Abrial supposed he had authority over Alexander, and resumed his habit of making grandiose patriotic statements. At this point, the words gloire, honneur, and drapeau tended to make British generals roll their eyes.

For his part, Alexander, the most reserved, polite (and solidly realistic) of generals, remained unmoved by Abrial’s rhetoric. “He considered the salvation of three of the best divisions in the British Army more important than amity with the French, whose fortunes already seemed to him beyond repair.”

It is perhaps a pity that Alexander did not speak French better (he would have to take French lessons after the war when he was appointed governor general of Canada), but the message he had for Abrial was in any case not one the admiral wanted to hear—the Royal Navy did not think the evacuation could be continued past the night of June 1–2, and Alexander’s orders were to get as many of his men out by then, not to fight a last-ditch battle alongside the French.

Abrial was not comforted by Alexander’s promise that French soldiers would be evacuated on what Anthony Eden, secretary of state for war, described as “a 50-50 basis,” a reaction to Churchill’s somewhat rash promise to Premier Reynaud to leave “bras dessus, bras dessous.” This was partly because Abrial still thought it was his job to defend Dunkirk, partly because the French forces repeatedly failed to liase with the British senior naval officer. Over the next few days many ships continued to make the dangerous crossing to pick up French troops only to find there were none there at the appointed time. Still, Alexander did his best to obey his orders: over the next three days during which he was in command of the BEF, he would evacuate 20,000 more British troops and over 98,000 French, a far better proportion than the promised “50-50.” Owing largely to poor discipline and lack of liaison, however, many of the French troops “missed the ships, and the ships missed the men,” causing ill will both among the waiting sailors and the French.

Alexander was not exaggerating—losses of vessels of all kinds had reached so high a level that by June 1 evacuation was possible only in the hours of darkness. The perimeter was reduced to the point where German guns could reach not only everywhere on the beach and in the harbor but all the approaches by sea to Dunkirk. Despite the heroic efforts of Fighter Command, which were for the most part out of sight of the troops on the ground and the sailors, and despite mounting German losses in aircraft, the Luftwaffe appeared to control the sky during the daylight hours, bombing and machine-gunning vessels of every size and kind.

The bombing was relentless and effective, and it made no attempt to spare hospital ships, although they were clearly marked as such under the Geneva Convention—indeed at one point a message en clair was sent to the German authorities emphasizing that ships bearing the wounded were unarmed and painted white, but the only effect was to redouble German air attacks on them. The hospital ships went back and forth despite being bombed to the very end. The wear and tear on vessels of every kind and their crews mounted under the constant attacks. A direct hit was not needed to put a vessel out of action—the blast effects of a near miss sprung plates and rivets, or sheered steam lines and oil lines, putting countless ships out of action and littering the narrow approaches to Dunkirk with floating wrecks, adding to the dangers of navigation.

By now the British press was finally reporting on the Dunkirk evacuation wth relative frankness. The Times report was in fact remarkably accurate:

A withdrawal from a hostile coast while still engaged with an enemy is one of the most difficult of all operations of war. . . . The Navy’s difficulties have been by no means light. The Flanders coast is one of shallow waters, narrow channels from which all lights and most aids to navigation have perforce been removed, and strong tide streams by which any ship even temporarily disabled is liable to be swept ashore. To add to these difficulties, ships off the coast and in the ports have been subjected to continuous and intense air bombing. . . .

The piece marks a significant change from the Ministry of Information’s previous policy of manufacturing good news for home consumption and downplaying disasters, and also the first step in the transformation of Dunkirk from a humiliating military defeat into a proud national epic even as it was taking place. “Grin and bear it” might have been the new motto for Britain, in which the ability “to take it,” rather than any significant victory, became a source of national pride, and even of optimism.

The news reflected a dramatic change in British sensibility. Even “human interest” stories made no effort to spare the reader from the reality of what was happening, like that of the fifteen Red Cross nurses, “who by some mischance had got wet through by the capsizing of the little boat in which they were at first on their way to embark.” Taken on board by a minesweeper, “they were tired out and shivering, so they were at once put to bed between warm blankets.” The next morning, when they reached a British port, “they were presented with their uniforms, washed, pressed, and ironed by a member of the minesweeper’s crew who fancied himself as a laundryman. They landed fit for immediate inspection by [even] the most dragon-like of matrons.” (In those days a nurse’s uniform was a mass of knife-edged, starched creases.) No attempt was made to disguise the unpleasant truth that everyone was in full flight, or that the nurses had been rescued from a capsized small boat. It was a story that would have been vigorously censored only a few days before, like those of the special trains carrying thousands of “tired and battle-stained troops” from the Channel ports to be returned to their regiment and rearmed. Without disguising the scope of the German victory, the press was at last reflecting the truth: the bulk of the BEF had escaped and was home. Britain, unlike Holland, Belgium, and soon France, would be accorded a breathing space, a time for the German generals and their Führer to contemplate the gray, choppy waters of the English Channel and try to decide whether to cross it or not.

Hitler was ambivalent on the subject of invasion. His mind was still set on the conquest of France, which seemed a bigger challenge than it turned out to be. The generals, particularly Halder and Guderian, complained that “the enemy are getting away to England right under our noses,” forgetting that only a few days before they had decided that the area around Dunkirk was poor tank country, with its many canals, sandy dunes, and marshes, but Hitler himself did not seem disturbed. Some of those closest to him thought that he was moved by higher geopolitical ambitions, envisaging a world that would be ruled by Germany and Britain, and that sparing the BEF would be a shrewder move than destroying it, others that he was waiting for a peace offer from London, perhaps the final ripple from Halifax’s démarche with the Italian ambassador on May 27. The notion that a political crisis in Britain might place “the right people” in power and bring about peace talks was not, in fact, all that far-fetched. Had Chamberlain still been in office as prime minister, or had Halifax succeeded him, that is no doubt exactly what would have happened. But Churchill was by now firmly in power, and the notion of a fight to the finish was becoming fixed not only in his but in the British mind, even among those who until only a few days earlier had been in favor of joining the French in asking for terms.

The trains and railway stations crowded with exhausted and disheveled soldiers who had been evacuated from Dunkirk raised British spirits, rather than depressing them. Ambassador Kennedy, still the most persistent of appeasers and defeatists, might cable Washington that things “could not be worse,” that in his opinion the Germans would be willing to make peace, “on their own terms, but terms that would be a great deal better than they would be if the war continues,” and urge the British government to ship its gold and securities to Canada at once, but these were no longer opinions that were being listened to in 10 Downing Street, nor even in the White House at this point. Churchill did not need a propaganda minister like Joseph Goebbels—he was his own best propagandist, and his instinct that the British would rally when their backs were to the wall was proved correct. The good news that the Führer expected to hear from London never came, and the “right people,” far from taking power, would soon be dispersed, among them Lord Halifax to Washington as British ambassador, Sir Samuel Hoare to Madrid as British ambassador, and the Duke of Windsor to the Bahamas as governor. It was the most British of coups, in which those who had favored peace talks with Germany were simply shuffled off the stage far from Westminster to important jobs on the periphery of power, where they were to remain for the rest of the war. Henceforth Churchill would never need to worry about criticism for having chosen to fight on—the example of France would serve as a constant reminder of what surrender would entail.

Throughout the day of June 1 French troops camped out as best they could in the high, rolling sand dunes behind the beach at Dunkirk—the town of Dunkirk was now a death trap—in the absence of any organized plan for their evacuation. The rear guard of the BEF continued to march west toward the port, some of it in good order, as befits fighting troops. General Alexander remarked on his disgust at seeing the number of weapons that had been abandoned on the beach—he had not yet realized that many naval officers were ordering troops to leave their weapons behind—and his pride at watching battalions of the Foot Guards marching toward Dunkirk in step, as if they were on parade. He himself had reached the beach on a bicycle, having abandoned his staff car and set it on fire, together with his kit, so that he carried only his revolver, his field glasses, and his briefcase. With the practicality that had always marked his career, Alexander had his “divisional engineers [drive] their lorries on to the beaches at low tide and bridge them with a superstructure of planks to make a pier. Thus, when the tide came in, small rowing-boats could take off six or eight soldiers to small ships or other craft waiting to receive them. The plan was that every boat-load taken off would have someone detailed to row it back for the next consignment. I was not very pleased with the response.”

Alexander was displeased that not many men wanted to row a boat back to the beach once they had reached a ship, and thus many boats were simply abandoned, compounded by the fact that few landsmen were skilled at handling them in rough water and strong tides. Alexander pointed out correctly that the only way to get large numbers of troops off efficiently was from the mole, “where complete units were embarked onto destroyers, corvettes or ferries” under the command of their own officers. It was possible to take more than a thousand men on a destroyer, many of them in good order and still carrying their rifles—there are photographs of huge stacks of rifles being collected at Dover—and by June 1 the mole, though under constant gunfire, was the principal means of evacuation.

Many soldiers still tried to embark from the beach, rather than make the long trudge through the sand to Dunkirk, which was still under constant bombing and bombardment. Unless they were ordered to do otherwise, their first instinct was to get onto anything that floated, or promised to float. Even the mole offered no security. Bombs had destroyed many stretches of it, and the gaps had been covered with precarious planks. It was no easy task to walk along it single file under fire, and many preferred to take their chances on one of the many boats that had washed up on shore, or had been stranded by the tide, often improvising oars out of whatever flotsam and jetsam they could find. One soldier remembers that “the beach was filled with masses of troops mostly under no command, with equipment of all kinds strewn everywhere.” Another, Clifford Holman, remembers his “mate” lying down on the beach after days of marching under fire while he went off to find out what was happening, only to be told that it was now “every man for himself.” Holman went back to find his mate sitting upright in a shallow trench, dead. He hailed a passing Royal Army Medical Corps officer to tell him his mate “was dead with no marks.” The officer paused briefly to say, “It happens, soldier,” then took the dead man’s identity tags, and said, “You bury him, if you wish.” Holman joined a group of men on a Bren Gun Carrier (a small, lightly armored tracked vehicle then popular with the British Army) and tried to run it as far out to sea as they could. When it stalled, they swam back to the beach and found an abandoned rowboat, but no oars. They improvised oars, squeezed into it, thirteen men in all, paddling and bailing with their helmets until they reached a barge, at which point their boat capsized and they were pulled aboard, and arrived fourteen hours later in Ramsgate.

There were hundreds, indeed thousands of such stories, of men who by sheer perseverance managed to get off the beach, rather than join the immense queues at the mole. One soldier remembers swimming a hundred yards out to sea to haul in an abandoned rowboat and rigging an improvised sail, another of boarding a vessel only to be trapped on board her when she was bombed and caught fire, and plunging into the sea half naked to float there until a passing boat saw him and threw him a line. The basic thread to all such stories was the deep desire to get back to Britain whatever the difficulties and danger, and the belief that anything would be better than to be captured by the Germans, which, from the stories of those who were, was certainly true.*

Across the years, Saturday, June 1, 1940 sticks in my mind, since I remember that my mother, with some of her actress friends, went to one of the London railway stations that day to help pass out tea, sandwiches, “buns,” and cigarettes to the returning troops. As a result I heard from her what was happening—perhaps because as a glamorous West End star they felt they could talk more freely to her than to women in uniform, more likely because she was simply good at drawing people out. At any rate she came home with a clearer view of the retreat and the evacuation of the BEF than most people had at the time.

Insufficient attention has been paid to the success of the immense and hastily improvised plan to provide trains at a moment’s notice for several hundred thousand men, almost as remarkable a feat as the mobilization of nearly a thousand ships. Hundreds of passenger trains (one source lists a total of 569 trains, carrying a total of over 330,000 men) had to be provided, moving over already overcrowded lines to comparatively small railway stations on the southeast coast of England, then routed to take the men to places where they could be housed, fed, reclothed, and redeployed. This required close cooperation between the director of movements at the War Office and the traffic departments of the major railway companies (in those days, before the postwar Labour government nationalized the railways and created British Railways, there were four major railway companies), and a complex plan had to be developed overnight to prevent this huge number of trains from getting snarled up, or stopping all other railway traffic throughout the country. Very few of the trains were routed through London, not from any desire to hide the evacuation from the capital, but because the main London stations were not the most direct route to the north and west. Some of the trains, from the LM&S (London, Midlands and Scottish) Railway, were routed through Kensington Station (Addison Road), and that is probably where my mother and her fellow actresses passed out tea and buns.

She was not alone. The trains stopped at stations all over southeastern England, and although there was no direct order to do so, they were met everywhere by uniformed members of the Women’s Volunteer Service and the Red Cross, as well as by civilians of all ages bearing everything from bottles of beer to dry socks—no triumphant army could have been greeted with more enthusiasm or on a greater scale. It was like a national party, starting at Dover, where “the ladies meeting us as we disembarked gave each man five Woodbines [a cheap brand of cigarette] and a bar of chocolate and an apple.” As if the tradition of British reserve had momentarily broken down, young women leaned into the windows of railway carriages to kiss total strangers. Others handed in telegraph forms and postcards so that soldiers could inform their families they were still alive. In some places people popped open champagne bottles and passed them around. It was as if the British had won the war rather than been driven out of the Continent. Joan Launders, then an “English schoolgirl, complete with panama hat and blazer,” passed out bouquets of flowers to soldiers as the trains halted in a Kent village station not far from her school, and helped distribute egg sandwiches to the troops from trestle tables on the platform.

The troops, she remembered, “were very mixed. Some cheerful, some so sound asleep we didn’t rouse them, others just sitting with blank staring faces. Poor men. Various nationalities too. I spoke to Frenchmen . . . and one colored man in baggy white trousers, red waistcoat and a strange hat who came from heaven knows where. . . .† Some were wrapped only in blankets. Others were quite spruce but all had the strained look around the eyes that shows when anyone has been through a hard time.”

Authority, discipline, and class consciousness were all abandoned for a brief moment. The vast mob of men, some of them still armed, got into trains and made their way willy-nilly, virtually without orders, to wherever their train took them. Nobody deserted, many got off their train when it stopped at a local station to telephone their family or their girlfriend, and not a few were taken in by total strangers and given a bath, a chance to shave, and a meal before boarding the next train.

They presented an unusual spectacle. Mrs. Anne Hine, who was on holiday in Blackpool remembers “the hush that fell over the promenade” as a column of soldiers came out of the station. “That was not an uncommon sight in Blackpool because the town was then full of troops but these were different. They were dressed in assortment of odd uniforms, some had no caps and I remember clearly that some had no boots and their faces were drawn and tired. . . . I stood to watch them pass with tears streaming down my face.”

Tears streamed down my mother’s face too, as she told me about her day at the station, although she emphasized how “cheerful” the soldiers had been. The wounded had been hard for her to take; many had been hastily patched up on the beach or in Dunkirk before being evacuated, and although the most seriously wounded had been left to the mercy of the Germans, together with the RAMC personnel looking after them, some of the walking and stretcher-borne wounded were in terrible condition. All of them cheered up at the sight of actresses and showgirls passing out tea and food. “Oh, they were so brave,” my mother said with an effort at gaiety. My father, who had seen similar scenes in 1917 and 1918 as the Austro-Hungarian Army struggled toward defeat, nodded darkly. The railway stations in Vienna and Budapest in 1918 had been full of brave cheerful wounded men, but that had not saved Austro-Hungary from defeat. Still, as my mother would have pointed out, Austro-Hungary was not an island.

_________________________

* Most films about Allied prisoners of war in German hands deal with officers or aircrew and present a glamorized picture of what it was like to be a POW. The Geneva Convention allows “other ranks” (i.e., not officers) to be put to any work not directly related to war production. Many of the British soldiers captured at Dunkirk were beaten, marched under horrendous conditions through France, Holland, and Belgium, then shipped in cattle cars to POW camps in occupied Poland and put to work in salt mines or the equivalent on starvation rations for five years.

† Probably from the French colonial troops, perhaps a Zouave or a Sénégalais Tirailleur.