The “little ships.”

The “little ships.”

I DON’T REMEMBER FEELING any fear at home myself, but then I was approaching seven, not an eleven-year-old. My mother was congenitally unafraid—she was moved to tears by the plight and the courage of the soldiers returning from Dunkirk, but not at all afraid of invasion, which I am sure she never imagined would take place. As for my father, he was too busy to be afraid, his mind was on his work. Nothing short of the arrival of a German tank outside the door of our house in Well Walk, Hampstead, would have deflected his attention from the films Alex was planning.

Well Walk, Hampstead.

Perhaps one of the reasons for the calm with which the British faced the defeat of their army and the possible invasion of their island was the perfect weather. Most, if not all, the photographs of the Dunkirk evacuation and the return home of the troops were taken in black-and-white, and as seen in newsprint they look bleak and gray, but late May and early June are the loveliest months in a country not famed for its good weather.* The fact is, the weather was beautiful; everywhere the flowers were in bloom and the trees in full leaf. Our garden at home had never looked prettier (whose job it was to keep it that way I do not remember), even I remember it. Looking at photographs of the time one might conclude that the whole nation was in a state of fear and collapse, but such was not the case. Flower shows, garden parties, and the neat, tidy merrymaking in London’s parks (and nearby Hampstead Heath) went on as usual. Children sailed their boats, people walked their dogs, or rode, or fed the ducks—life went on as usual. Only an occasional glimpse of reality, like my mother’s at the railway station, shattered the illusion that it was just another perfect early summer. If the Germans’ intention was to terrify the British, they failed. They read and listened to the news with attention, but did not have the sinking feeling of collapse that pervaded France—that is the advantage of the Channel. The Germans had reached it, with catastrophic consequences for the allies, but could they cross it? The British are never more irritatingly secure of themselves than when they are alone, looking out at the chaos in Europe across the gray, choppy waters of the Channel.

In those days of course it was not possible to stay “glued to the television set” for days during major historical crises, as it is today, or even to the radio, but my father read the morning papers, the afternoon papers, and the evening papers, and even my mother glanced at the headlines—the theater generally absorbed most of her attention, and people were still going to it, eager to forget what was happening for a few hours of entertainment. The theater and the cinemas never did better business.

My father spent most of his days at the studio, but he was now working at his drawing board. Some of his sketches he brought home in a big artist’s portfolio, to refine at night—some of them were in brilliant color, not the usual black-and-white, and while I did not know it, they were for new sets for The Thief of Baghdad, the Technicolor extravaganza that had been languishing since the outbreak of war, but whose completion was vital for Alex’s survival.

By then my father must have known that it could not be completed in England. Alex’s wartime flights back and forth to America had been increasing in frequency—not that anybody mentioned that to me, so far as I knew he was still living in his mansion on Avenue Road. Certainly by May he had already decided that The Thief of Baghdad could only be completed in Hollywood, and it had already been made clear to him that his second most important task was to complete That Hamilton Woman as quickly as possible. California held no particular attraction for Alex; even when he lived there in the late twenties, he had hated everything about it, from the avocados and swimming pools to the studio moguls. Like a buccaneer, he had returned there from time to time on swashbuckling raids that brought him to a seat on the board of United Artists or deals that made it easier to distribute his pictures in the United States—he was at once the equal of the studio heads in Hollywood and their rival, determined to create a motion picture industry in Britain that could compete with them on equal terms.

In Charles Drazin’s superbly detailed biography of Alex much is made of his close connections with the British Secret Service and his friendship with Winston Churchill, and both those things, apart from taste, sophistication, culture, and a certain weary grandeur, set him apart from the other Hollywood film moguls.

Certainly he was eager to rejoin Merle again. They had only been married for a few months, before she left for Hollywood, shortly after the outbreak of war, and made it clear that she preferred to remain there, but the main reason for his return there was his conviction that British “propaganda” films, if they were to have any influence on Americans, must seem to be American products, and not imitations of ham-handed, boastful propaganda films from Germany, which nobody wanted to play, or see. His job was not to convince Americans that Britain could fight but to produce in America a certain sympathy for Britain and for the British cause. This conviction was shared by Churchill and Duff Cooper, “both of whom,” to quote Drazin, “nudged him towards the Hollywood option as not only the best way of serving his own but also Britain’s interests.”

Those most famous of lovers, Laurence Olivier and Vivien Leigh, both of them under contract to Alex, were already in Hollywood, thus the pieces were set in place for the making of That Hamilton Woman; financing for it was deftly aided with the help of His Majesty’s Government, so Alex set off for America once again with a brief to make the story of Nelson and Lady Hamilton into what would appear to be a star-studded, lavish Hollywood historical drama. Apart from the stars themselves, one of the most important of those pieces was my father, whose job it was to endow it with the look of a glossy Hollywood production—it was to be a quintessentially English story, although produced, directed, and art-directed by Hungarians, and masquerading as an American picture.

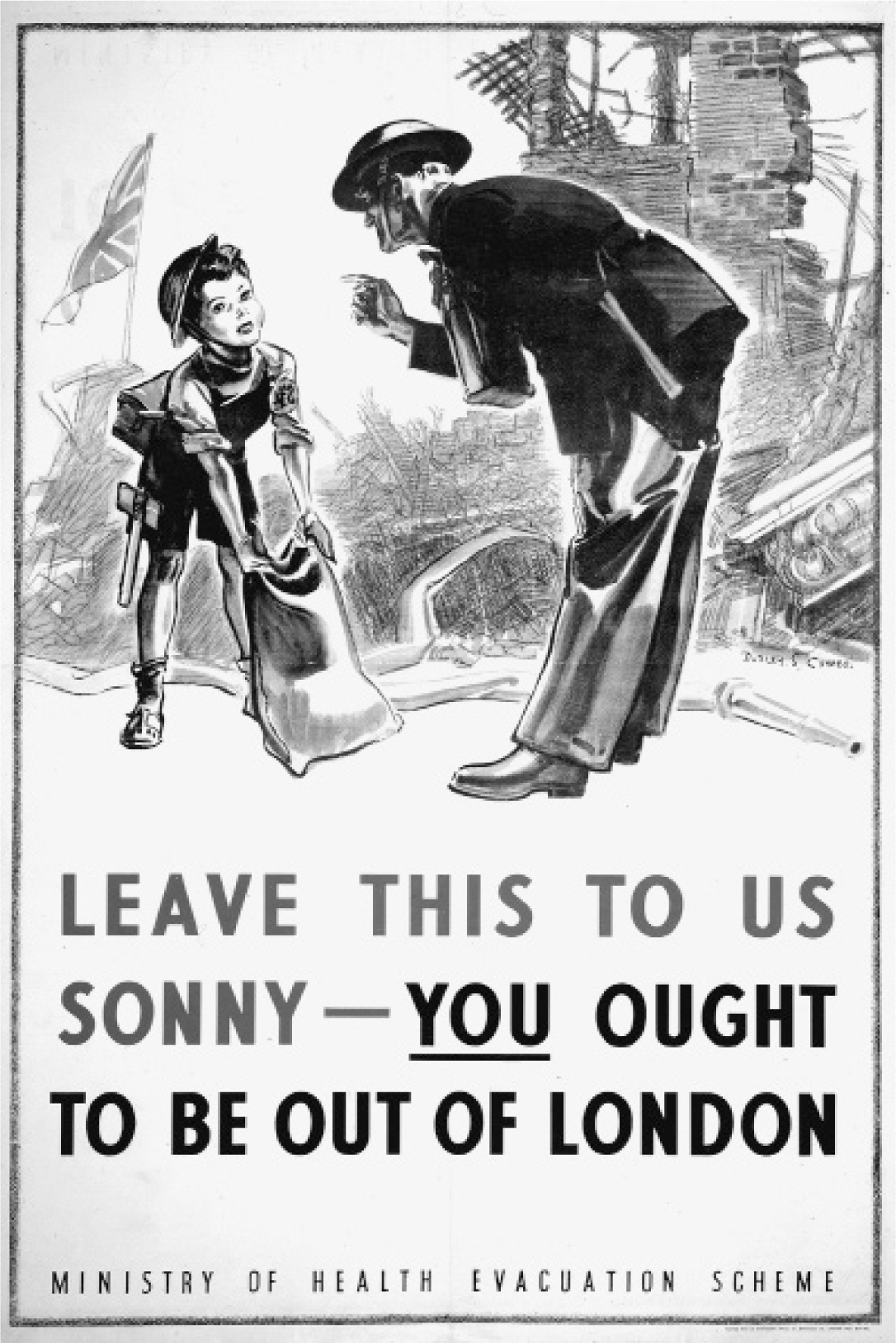

Even as I was having the newspaper stories about Dunkirk read aloud to me by Nanny Low, arrangements were being made to ship me to America. These coincided with the peak of the British government’s controversial plan to evacuate children just in case the Germans did manage to invade. This scheme had been hatched when Chamberlain was prime minister, under the then current belief that the war would begin with gigantic air raids that would destroy London and other urban centers. Once placed in the hands of the bureaucrats, it quickly grew beyond anybody’s expectations, and would ultimately lead to the evacuation of nearly three and a half million people—an immense, confused, and poorly supervised social movement on a scale better suited to one of the totalitarian countries than to Britain. Complaints about it from families whose children were taken away from them were equaled only by the complaints from those who were ordered to take them in.

The prime minister, perhaps understandably, does not seem to have been aware of the scale of the exodus, or of the number of children who were being sent overseas, a relatively small (and privileged) fraction of the total. In reply to a question in the House of Commons on the subject, Churchill replied, “I must frankly admit that the full bearings of this question were not appreciated by His Majesty’s Government at the time it was first raised. It was not foreseen that the mild countenance given to the plan would lead to a movement of such dimensions, and that a crop of alarmist and depressing rumors would follow at its tail, detrimental to the interests of National Defense.”

Nothing, however, could stop or slow down a plan that had already been so firmly implanted by the civil service on such a broad scale. Churchill did not disguise his dislike of the schemes for evacuating. In reply to a question about whether he would like to send a message to the prime minister of Canada to be hand delivered by one of the evacuated children, he replied rather testily, “I certainly do not propose to send a message by the senior child to Mr. Mackenzie King, or by the junior child either. . . . I entirely deprecate any stampede from this country at the present time.”

I would have agreed with him, but my own opinion was not of course sought.

Looking back on it, I now realize that my mother was strongly against leaving for the United States, and that my father’s insistence on moving us all was very likely the first, and perhaps the most important, of the disagreements that would lead them to divorce after my father returned to England in 1941. In her case, she remained so ashamed of leaving England in 1940 that she could not bring herself to go back even for a visit for several decades after the war. She remained as unmistakably English as ever, but transplanted reluctantly to America. In my father’s case, the matter was very simple—what Alex wanted, he would always do, and that was that. Alex’s formidably efficient secretary Miss Fisher was already in Los Angeles, and had rented a house on North Rodeo Drive in Beverly Hills for us before my father had even told my mother of our impending move.

The departure of children then was controlled by numerous regulations as a part of the general scheme to evacuate children from urban centers, but in practice it was limited only by the difficulty of finding passage on board a ship, and of securing an entry visa into the United States, easy enough to obtain in those days for families that had relatives or friends there. The wealthy and the well connected had little difficulty in evacuating their children, and over seventeen thousand were sent overseas by their parents in the six months after June 1940, not an inconsiderable number considering the limited number of passenger ships crossing the Atlantic in wartime. Their number included the future historians Sir Martin Gilbert, Sir Alistair Horne, and John Julius Norwich, Duff Cooper’s† son. That indefatigable gossip and diarist Chips Channon MP sent his son, Paul, to America in 1940 and described “a queue of Rolls-Royces and liveried servants and mountains of trunks” on the platform of Euston Station as Paul departed in a train full of children, but this may merely be a dig at Duff Cooper, the fierce opponent of Chamberlain and appeasement, nevertheless taking the opportunity of sending his son to safety.‡ At the time no particular shame was attached to sending your children to safety if you could afford it, nor did I feel any when I was bundled off from drab, smoky Euston Station to Liverpool, in the summer of 1940, still wearing my gas mask on a strap around my shoulder, as well as a package on a string around my neck containing my passport, my pocket Bible and travel documents, to board the SS Duchess of Richmond, along with hundreds of other children, bound for Montreal. What I remember best was the grayness of everything. The ship was painted wartime gray, the sea was gray, most of the interior had been painted a dull, flat gray too, covering up what had doubtless been elaborate woodwork and decorations. The portholes were covered over to prevent any light from attracting a U-boat, and the atmosphere was anything but cheerful, what between seasickness and homesickness. I do not think there was any child on board who would not have preferred to go home, but given the natural curiosity of children there was a certain excitement when, in the end, we came in sight of Canada, unpromising as its shoreline looked. Other than that the journey remains a blur, perhaps fortunately.

The spirit of Dunkirk, now ingrained in the British consciousness, did not emerge immediately or take hold as completely as is now supposed. If a cabinet minister like Duff Cooper could send his son abroad after Dunkirk without causing comment, it is a fair conclusion that many people still remained anxious about the possibility of a German invasion, despite the national habit of putting a brave face on things. The contrarian Clive Ponting points out that the “Children’s Overseas Reception Board,” a hastily contrived scheme to arrange for the evacuation of children to the Dominions, received over 210,000 applications between June and July 1940, when it was abruptly terminated because of the sinking of two passenger ships bearing evacuated children across the Atlantic—certainly an indicator of some degree of pessimism in the upper classes about Britain’s chances. Not until the Battle of Britain had been won in the autumn of 1940 did people begin to believe that whatever else Hitler might have up his sleeve, a German invasion was no longer likely.

King George VI spoke for the whole nation when he wrote to his mother Queen Mary after the fall of France, “Personally, I feel happier now that we have no allies to be polite to and to pamper.” Dunkirk is not unrelated to the emotions of those who demanded “Brexit,” the British exit from the European Union in 2016. There was a national sense of relief in 1940 at leaving the Continent and withdrawing behind the White Cliffs of Dover.

Some might question whether Britain could win the war without allies, but most felt that the French had been a troublesome ally from scratch, having failed to show the right spirit from the very beginning of the German attack on May 10, even though French casualties far outweighed those of the British (and, for that matter, the Germans) in the battles of June 1940: over 90,000 French dead, 200,000 seriously wounded, and 2,000,000 sent to hard labor and starvation rations in Germany for five years as prisoners of war.

The transformation of a calamitous defeat into a legendary victory was one of the singular British triumphs of the war, one that would sustain the people through the next four years, during which they were overshadowed by their two more powerful allies, the Soviet Union and the United States, and for over seventy years thereafter, and doubtless will continue to do so whenever they look across the Channel toward the Continent, for Britain never suffered invasion, occupation, or the marching away of millions of men into captivity. Despite the horrors of five more years of war Britain managed to stand alone until June of 1941, when Hitler attacked the Soviet Union, and December 1941, when Japan attacked the United States—surely Churchill’s greatest achievement.

In that sense Dunkirk was, and remains, perhaps the greatest British victory of World War Two, that rarest of historical events, a military defeat with a happy ending.

_________________________

* Since George II the sovereign’s birthday has been officially celebrated early in June no matter what date he or she was born, since the chances of good weather for parades, garden parties, and grand ceremonies like the Trooping of the Color are better than at any other time of the year. The early summer of 1940 was exceptionally nice, although exhausted men standing up to their neck in seawater at Dunkirk were unlikely to notice it.

† Duff Cooper was to become Viscount Norwich in 1952.

‡ Paul Channon, then five, managed to reach Rhinebeck, New York, where he went to a tea party given by Helen Astor, which President Roosevelt attended. As the president left, Paul shouted, “I hope you beat Mr. Wilkie!” The president remarked, “He’s beginning his political career young!”