I woke up six times during my last night in our house in Stoneybrook. Each time I did, I checked the digital clock that was still plugged in by my bed.

I woke up at midnight and had to go to the bathroom. Then I woke up at 1:33 after a dream about being chased by a bulldog. At 2:56 I leaped out of bed to make sure I’d remembered to put something important in my purse. (I had.) At 4:07 I woke up thinking about the moving men. They would arrive in three hours and fifty-three minutes. At 4:48 I had to go to the bathroom again. At 6:10 I just woke up. I don’t know why. But I was mad because my alarm was going to go off in twenty minutes, and the night already seemed like a waste, sleep-wise.

Mom and Dad and I fixed a strange breakfast that morning. We were trying to eat up what little stuff was left in the refrigerator. I had some yogurt, an apple, and a piece of bread. (The toaster was packed.) Mom and Dad had cottage cheese, bologna, and oranges. Yech.

Nobody was in a very good mood.

“Those movers better get here on time,” said Dad. “They better not be late. If they’re late …” I waited for him to finish his threat, but he didn’t. He just rolled up a piece of bologna and stuffed it in his mouth.

Mom fluttered nervously around the kitchen, trying to stay organized.

“Put all your trash in here,” she told Dad and me, pointing to an empty grocery bag. (We were eating off paper plates and using plastic spoons, forks, and knives. The kitchen was practically bare.) “Then, Stacey,” she went on, “put anything that’s left in the refrigerator and the freezer into this other bag and we’ll give it to one of the neighbors. Oh, put the rest of the paper plates and things in, too.”

Breakfast seemed to be over when Dad stopped rolling up bologna slices and Mom began pulling out drawers and opening cupboard doors, checking (for at least the tenth time) to be sure that they were empty. I filled up the grocery bags with our few leftovers and set the bag on a counter. Then I went upstairs to my room. I stripped my bed, folded the sheets and blanket and spread, and placed them in the one carton that was still in my room. This is what my room looked like: stripped bed, empty bookcase, empty bureau, bare desk, two chairs without any clothes thrown on them. My closet was completely empty. The lone carton sat in the middle of the room next to my purse. I added my nightgown and the digital alarm clock to it. Even though I knew that nothing else was left in my room, I began doing what Mom was doing downstairs. I looked into every drawer and even under my bed to make sure I hadn’t forgotten to pack anything.

When that was done, I sat down on the edge of my mattress. A tear slid down one cheek. I wiped it away with the back of my hand, but another tear followed, and then two more, and then a river. I hated the sight of my empty room, even though I knew that pretty soon my room in New York would look a lot like the way my room in Connecticut had looked. Except that outside the window would be a view of the apartment building across the street, the Blue Pan Coffee Shop, and a locksmith. (Mom and Dad had taken pictures from the window of the new apartment.) And the room would be smaller than this room. And we’d have to put roach traps in the corners because you just have to do that in New York. It’s part of city life.

I heard the movers arrive, but I didn’t want to go downstairs yet. Instead, I stood up, crossed the room to the carton, reached inside, and pulled out the manila envelope that was at the very bottom. I sat on the floor and opened it. Inside were the farewell cards the kids had given me at the party.

GOOD-BYE, STACEY, read Jamie Newton’s card. Jamie had written his name inside, but his mother had written everything else.

I WILL MISS YOU. YOU WERE FUNNY. AND NICE, Karen Brewer had written. She’d drawn a picture of a witch on the cover. I knew the witch was supposed to be Morbidda Destiny, not me.

ROSES ARE RED, VIOLETS ARE BLUE, GOOD-BYE STACEY, I’LL ALWAYS MISS YOU. That was Vanessa Pike, who planned to become a poet.

At last I looked at Charlotte’s card again. I WISH YOU WERE MY SISTER. Oh, Charlotte, I thought. I wish I were, too. Then we wouldn’t have had to say good-bye. We could stay together, because sisters do.

I put the cards back in the envelope, and the envelope back in the box. Now what? I couldn’t go downstairs because my eyes were still red.

“Stacey!” I heard someone call. “Hey, Stacey!”

The voice was outside. I ran to my window.

“Oh, my gosh!” I exclaimed. I didn’t know whether to laugh or cry. I think I started to do both.

The rest of the members of the Baby-sitters Club were standing in the yard below me. Stretched between two of them was a bedsheet. On the sheet, in dripping blue letters, had been painted the words SEE YOU SOON, STACEY.

Kristy was grinning up at me while she tried to straighten out her end. Dawn was tugging at the other end. Claudia was the one who had shouted to me. Mary Anne was just standing there crying.

“I’ll be right down!” I shouted to them.

“Okay!” Claudia shouted back.

I grabbed my purse and ran downstairs. By the time I reached the front yard my parents were already there, admiring the sheet.

“You guys are too much,” I told my friends. I felt like hugging them all, but knew we’d be doing plenty of that soon enough.

“This is for you,” Kristy said, indicating the sheet. “To remember us by.”

“Gee, do you think it’s big enough?” I joked, and we all laughed. I turned to Mom and Dad.

“Can I keep it?” I asked.

“Of course,” replied my father. “Most kids want to keep a dog or a cat. All you want is a bedsheet.” (His good humor must have returned when the movers showed up on time.)

Mom and Dad went inside then to direct traffic. Kristy and Dawn folded up the sheet and handed it to me. “Thanks,” I said, “and now I’ve got something for you guys.”

My friends looked interested. Mary Anne dried her tears.

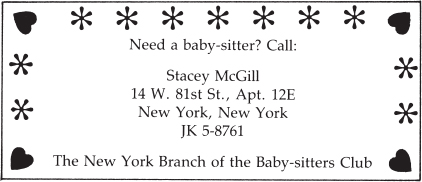

“Don’t get too excited,” I warned them. “It isn’t much.” I reached into my purse and pulled out the thing I’d leaped from my bed to check on at 2:56 that morning. It was a packet of calling cards. Mom and Dad had had them printed up just for me. This is what they looked like:

“I realized I hadn’t even given you my new address or phone number,” I told my friends. “Now you’ve got everything. Plus, see? I’m not going to forget the Baby-sitters Club. In fact, it’s going to grow.”

The five of us sat on the front lawn and watched the movers haul every last thing out of our house and load it into the van that was parked in our driveway. While beds and tables and boxes and bags went by, we talked and giggled. We promised to write, to phone, to visit. But sometimes, there were long silences. I didn’t like them. I felt as if I should be filling them up. During one of them, I retrieved the bag of leftovers and handed it to my friends. “Take whatever you want,” I told them. “Mom doesn’t want to waste this stuff.”

Finally the van was loaded. After a last tour through our empty, echoing house, my parents climbed into the car. It was packed with suitcases, just in case anything should happen to the van on its way to New York.

“Come on, Stacey!” called Dad.

I faced my friends. “How can I say good-bye to you?” I asked them.

They shook their heads. Then Mary Anne held her arms out and we hugged. After that, I hugged Kristy, Dawn, and finally Claudia. Claudia and I hugged the longest of all. As we pulled apart she handed me a long envelope.

“Open it in the car,” she whispered.

I nodded. I couldn’t talk. I fled to the car, crawled into the backseat, and nestled between my bed pillows, which Mom had put there for me.

The van pulled slowly down the driveway, and we followed it. I gazed out the window. Claudia, Kristy, Dawn, and Mary Anne were still standing on the lawn. “Good-bye, Stacey! Goodbye!” they called.

I waved until we turned a corner and I couldn’t see them anymore. Then I opened the envelope from Claudia. Inside was a letter. It was thirteen pages long. “Dear Stacey,” it began, “I bet this will keep you amuzed intil you get to NY. City.” I smiled. The letter was full of jokes, riddles, gossip, the details on how Dori and Howie had suddenly decided to break up (Dori had returned the ring, so Howie was now stuck with something of mine!), and Claudia’s thoughts about our friendship.

“Maybe I will never have another best friend,” she wrote, “but it would be wirth it. I mean it would be wirth it to have had you for my best freind even if it was for just a yer. You will always be my best best freind if you know what I mean. What I mean is I might get another best freind sometime but she wouldnt be as good a best freind as you.”

And you, Claudia Kishi, I thought, will always be my best best friend.

We turned onto the highway. I was ready. Ready for New York and whatever it held for me.