Chapter 10

Food . . . for Thought

Food—the first enjoyment of life.

—Lin Yutang (1895–1976), Chinese writer and philologist

Ever since we left the security of the womb, food procurement has been high on our list of needs. It’s one of those basics which, along with air and water, we can’t live without. But food is special. Unlike air and water, food must be planted or born, nurtured, and then harvested. There are very few of us in the so-called civilized world who plant, grow, catch, or raise all of our own food. We don’t grow the vegetables, fruits, and grains, nor do we raise the chickens, cattle, or pigs that we eat. Most of us trust others to do all of these things.

When it comes to food, everyone is an authority so it’s not surprising that we have plenty of advice on the subject. While the content of this chapter is not intended to help you lose weight or change your eating habits, it may have that effect depending on your conclusions from the risk discussions to follow. The exposures are relevant today and, as you will see, they may be more important for future consumers. All of us may be food experts, but are we asking the right questions? Are we providing adequate regulations and safeguards for our and our children’s generation?

Generally speaking, new scientific discoveries and, of course, health-related incidents have been the primary causes for changes in food safety regulations. But science is not always a part of the solution. Sometimes it’s the cause, by creating new exposures. Other times technology helps us identify exposures that were always there, but which we just didn’t have the ability to see. In both cases, regulations have been either created or modified to mitigate the identified risks. This is a continuous process.

There is one example from history of how U.S. food safety regulations have changed that is particularly noteworthy. It represents a milestone about how our world was viewed in the era before technology and how it changed once the risk horizon was extended.

Paracelsus said, “The dose makes the poison.” Unfortunately, we always don’t know what dosage is “safe,” over what period of time, and for what age groups. The time delay required to observe the effects of some chemicals, even in clinical studies of rats and mice, is sometimes years. There is no doubt that some of today’s chemicals can cause problems. We know, for example, that our powerful, efficient pesticides can cause cancer in sufficient dosages. The question on our table is: How much residue is “acceptable” for us and for our children? To learn how U.S. policy started on this subject, let’s return to the Eisenhower administration of the late 1950s where I’d like to introduce you to a key figure.

Does the name James J. Delaney ring a bell? Unless you’re from New York City or a student of history, I doubt you know of him. Yet he probably has done more to shape the U.S. government’s policy on food safety than anyone else.

James Delaney was born on March 19, 1901, in New York City and grew up attending public schools in Long Island City [1]. In 1944, he was elected to the U.S. House of Representatives where he started out as a liberal with close ties to the labor movement. However, as his constituency changed in New York from a blue-collar enclave into an economically healthy and vocal middle-class stronghold, he became increasingly conservative. In 1946, he lost re-election, but regained his House seat two years later. After this, he won 15 consecutive elections. Mr. Delaney retired from the House of Representatives in 1978 where he had served for 38 years and moved to Key Biscayne, Florida. Mr. Delaney died at his son’s home in Tenafly, New Jersey, on May 24, 1987 [2].

Mr. Delaney’s legacy is the amendment to the federal Food, Drug and Cosmetic Act that carries his name. The “Delaney Amendment,” commonly called the “Delaney Clause,” outlawed the use of any substance in processed foods that is known to cause cancer, without consideration for the degree of risk. It says if a substance, pesticide, preservative, nutrient, or coloring caused cancer in any dose, it could not be used. This zero-tolerance or zero-risk approach seemed manageable in 1958.

But technology presents a double-edged sword. In 1958, when the Boeing 707 airliner went into service and the first micro-chip was invented, we knew of only a relatively small number of carcinogenic chemicals. Since then there has been a continuous avalanche of new substances. Currently, the EPA has approximately 20,000 products registered as pesticides that are formulated from about 850 different active ingredient chemicals, manufactured or formulated by more than 2,300 different companies, and distributed by about 17,200 distributors [3]. A lot has changed since 1958.

Just to give you an indication of the difficulty in complying with the Delaney Clause today, there are over 60,000 industrial chemicals regulated under the Toxic Substance Control Act. No one knows for certain how many of these are in our food supply [4]. Free-enterprise science is creating about 10 new products a day, a rate much higher than our ability to understand their effects.

Obviously, the Delaney Clause is no longer a manageable law. In addition to the myriad chemicals we produce, we’re now able to measure better than ever before. In 1958, scientists could measure concentrations down to the perceived minuscule level of 1 in a million. This seems pretty small. It’s roughly equivalent to being able to identify one drop of a substance in twelve gallons. Now we can measure down to 1 in a trillion. In numerical terms this is 1 in 1,000,000,000,000. Identifying one part of a substance in a trillion others is like picking one drop of liquid out of 17 Olympic-sized swimming pools.

We can’t perceive this level of detail. Most people have difficulty picturing a one-in-a-thousand or one-in-ten-thousand situation. Now that we can view our universe down to this level, we don’t like what we see. In 1958, when we thought we were safe, it was only because we were blind to the world beyond the 1 in a million horizon. Many of the carcinogens that Delaney outlawed were present, but at levels below our ability to detect them. Now that we can see a little farther, reality has set in. As a nation or global community, clearly with more problems than resources, we just can’t afford a zero-tolerance level.

In the first half of 1990s, the Delaney Clause was more of a curse than a blessing. Countermeasures were taken to work around the clause and its interpretation was liberalized. In other words, the once-rigid Delaney Clause was bent a little. People began to realize that it wasn’t practical, but before the zero-risk level could be changed, Congress had to set other limits.

Delaney’s zero-risk was replaced by a policy called “negligible risk.” This is the risk management philosophy under which we are living today. The idea that risk can be eliminated is dated to an era where our technological looking glass had a narrow view of the universe and risk management was thought of solely as an insurance term.

Now we’ll explore elements of our food chain and examine the systems that produce and transport these delicate commodities to our tables day after day after day. Each element integrates specific scientific and technological advances to enhance food quantity, quality, or safety. Just like technology caused the rejection of the Delaney Clause, I wonder how our “negligible risk” policy today will be viewed in fifty years. Think about this as you read the following food chain discussions.

Figure 10.1 presents the food chain components that will be discussed in terms of their risk exposures. There are many food chain characterizations and I am using this version just to acquaint you with the fundamental process components that take basic inputs and (most of the time) put sustenance in your body. Now let’s take a look at each element of this life sustaining sequence for most people around the world.

Figure 10.1 Food transport chain.

FARMLAND

The issue here is simple. In 1980 there were about 2,428,000 farms on 1042 million acres. In 2009 there were 2,200,000 farms on 920 million acres. Also during this period, the U.S. population grew from 250 million to 300 million people. Figure 10.2 shows these relationships from 1980 to 2009 [5]. So as the number of farms decreased by 9% and the number of farming acres decreased by 12%, the number of people to feed increased by 35%. The reduction in number of farms could come from consolidation but the decrease in farming acreage is a serious food risk issue for our future. Once farmland is lost to a shopping mall, housing development, or industrial park, it’s virtually gone. And since an inch of nutrient-rich top soil takes about 500 years to form [6], it should be treated with a great deal of respect.

Figure 10.2 (A) Number of U.S. farms and acres. (B) U.S. population, 1980–2009.

Obviously, there has been a significant increase in yields or productivity per acre. Table 10.1 shows some examples to give you a sense of the tremendous improvements that have been achieved by farmers and those industries who support them [7]. Crop yields vary each year depending primarily on the weather but the percentage changes shown in Table 10.1 are representative of actual productivity improvements over this time. If this wasn’t the case we would have either a smaller population, much higher food prices, or both.

Table 10.1 Crop Productivity Changes: 1980–2009

How can you get this much more food out of a reduced amount of land? Let’s see what variables you can change. The length of a day and the weather control the amount of sunlight, temperature, and moisture so there isn’t anything we can do about them except move farms to different latitudes. You can plant the crops closer together, but there are space limitations required by each seed or plant. (We’ll talk more about this in the next section.) Or you can increase the amount of nutrition in the soil. This is something you can control. Put your soil on agricultural steroids, that is, fertilizers.

Fertilizers have been around for as long as people have been growing food. Advances in our understanding of plant growth mechanisms have changed fertilizer applications from a simple fish dropped in a corn hill to a scientifically precise recipe. And one size does not fit all. Soil nutritional requirements can vary on the same farm and with the crops being grown. Farmers today have added soil chemistry to their job skills as they periodically assess soil nutrients to maximize crop yields. Too little fertilizer, too much, or the wrong chemical mix all have detrimental effects on crop yields, the environment, and profits.

Here’s a short primer on agriculture fertilizer that shows how precise fertilizer applications have become. There are 80 basic elements that occur in nature. Plants require only various amounts of 16 of them to support their lifecycle [8]. Crop production, first and foremost, requires carbon, oxygen, and hydrogen for photosynthesis. Plants convert sunlight, CO2 and H2O into plant sugars. Fertilizers are not needed here but this is just the start. All living things are built from DNA, deoxyribonucleic acid, a double-helixed molecular structure that stores genetic information formed by the sequence of four chemical bases: adenine (A), guanine (G), cytosine (C), and thymine (T). Plants and humans alike also store energy in the form of adenosine-triphosphate or ATP. This molecule is unique in the sense that it is the primary mechanism used by cells to transfer energy to other chemical reactions, one of which is cell division or growth. DNA strands and ATP molecules include carbon, oxygen, and hydrogen, but they also contain nitrogen (N), phosphorus (P), and potassium (K). To complete the list of the 16 elements, here are the remaining 10:

| Calcium | Copper |

| Magnesium | Zinc |

| Sulfur | Iron |

| Boron | Molybdenum |

| Manganese | Chlorine |

All of these chemicals together, in the right amounts, support healthy plant growth in a variety of ways including good leaf color, shape, resilient structures, size, and, of course, yields.

The main fertilizer ingredients nitrogen, phosphorus, and potassium are usually mixed together in different ratios to match soil needs. At feed stores and garden centers you’ll see fertilizer bags with three numbers separated by dashes, like 5-10-15. The code is a sequence that indicates the percent weight of available nitrogen, phosphate (P2O5), and potash (K2O), respectively. To convert the phosphate number to the percentage of phosphorus, multiply the second number by 0.44, and to get the actual percentage of potassium multiply the third number by 0.83. So a 100-lb bag of fertilizer with the code 5-10-15 has 5 lbs of available nitrogen, 10 lbs phosphate (4.4 lbs phosphorus), and 15 lbs of potash (about 12.5 lbs potassium). Today, farmers test their soil and then buy the right ratio and amount of nutrients to maximize crop yields. The days of qualitative judgment regarding fertilizer requirements are over for the high yield business farmer.

Nitrogen is a primary soil nutrient and it may sound odd that its scarcity could ever occur. After all, 78% of the air by volume is nitrogen so how can plants suffer from a lack of this element when it exists literally all around us? Nitrogen in the air is in the form of the stable molecule N2. In order for nitrogen to be useful for plant growth, it needs to be in the chemically active molecular form of NH3, or ammonia. The process of converting N2 to NH3 is called nitrogen fixation, wherein nitrogen is “fixed” into a form that chemically reacts with plant proteins to promote plant growth and health.

Some plants, like legumes (e.g., beans, soybeans, alfalfa, clover, and peanuts), perform nitrogen fixation as part of their natural reaction to common soil bacteria. Grain crops like wheat and corn lack this genetic advantage and they rely on the direct ammonia content of the soil or fertilizers. Nitrogen fixation does occur naturally to some extent in bacteria, algae, and lightning, but these sources are insufficient for soil nutrient enhancement.

Figure 10.2 clearly shows there is no shortage of fixed nitrogen and that farmers have been very successful in acquiring and using nitrogen-rich fertilizers. However, at the beginning of the 20th century, things were different.

In the early 1900s, most of the nitrogen-based fertilizers came from organic sources like concentrated bird dung called guano [9], imported from Peru, and from inorganic sodium nitrate mines in Chile. The demand for fertilizer was beginning to exceed supply and the political and business opportunities of fixing atmospheric nitrogen motivated entrepreneurs and governments alike to accelerate their research. One reason why governments were interested is because ammonia and related compounds are also essential ingredients in explosives.

Several researchers worked on this problem, but only one succeeded with a cost effective, industrial scale, workable process. It was a German chemist, Fritz Haber [10, 11], who along with Karl Bosch solved this world-scale problem. The Haber-Bosch process is being used today still as the primary source of fixated nitrogen. In 1918, Fritz Haber was awarded the Nobel Prize in chemistry for this achievement [12]. But his scientific talents had other, controversial applications. As a loyal, patriotic German chemist during World War I, he applied his technical skills to help his country develop poison gas. The active role he played, not only in producing poison gas, but also in its promotion and application, caused him to be criticized and censored by some scientific groups.

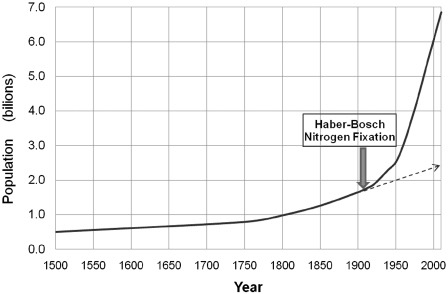

The Haber-Bosch process made enough fertilizer to continually feed the world’s growing population. The life-producing discovery made by Fritz Haber is demonstrated in Figure 10.3 [13]. The difference between the dotted line population forecast and the actual growth lines alludes to the significance of his achievement. To give Fritz Haber all of the credit for the marginal increase in population (∼3.5 billion people) perhaps is an overstatement, but regardless, it is safe to say today most of us owe a debt of gratitude to this somewhat forgotten man. Even if you’re not a science historian, you probably recognize names like Einstein, Maxwell, Planck, Mendel, or Freud, but the accomplishments of these and many more great scientists pale to the achievements of Fritz Haber. For this dedicated scientist created the process that enabled farmers to produce sufficient crop yields to support the population of this planet over the last century.

Figure 10.3 World population, 1500–2010.

Even though farm acreage has decreased over the past several decades, unit productivity, thanks to science and engineering, has grown at record levels. The question today is: How are we going to feed more and more people with the same amount of farmland in a safe, sustainable manner? Part of the answer lies in the next element of the food chain.

FARM PRODUCTION

Growing crops requires a mixture of science, art, and luck. The science relates to our understanding of the biological, chemical, and genetic drivers for robust plant growth, the art relates to our lack of knowledge of these drivers, and luck refers to the weather. But science, more than art or luck, is responsible for the tremendous gains in crop yields experienced over the past century.

Nature is dynamic. Everything living thing is constantly adapting to its environment. Survival demands this. This fact is common knowledge today but, as with all scientific knowledge, someone had to make the discovery. It was Charles Darwin [14] who first proposed the theory that plant as well as animal populations are constantly changing with variations or mutations that might improve productivity or proliferation. The animals and plants with such changes that make them stronger are more likely to survive and to pass these changes on to the next generation. This is a natural process with natural timing. Hence the term Darwin coined: “natural selection.” Then humans got involved. Take, for example, corn or maize, which may well be the most intensively altered food source (from its original form) that we grow today.

Contemporary corn has its roots in a short, grass-like plant called teosinte found in Mexico over 5000 years ago. It has a small cob, about 4 cm in length [15], with kernels arranged in scattered patterns. This is far less than the corn cob lengths and straight line kernel patterns that produce over 570 kernels per ear commonly grown today [16].

Early corn farmers chose the best ears of teosinte and propagated these grains as seeds, accelerating natural selection. These early hybrid engineers saw the benefits in a higher number of kernels per ear and in larger cobs. This process continued for generations but it wasn’t until Gregor Mendel’s work was applied that the science of plant hybrids really began to grow [17]. The fruit of this research was realized in the 1930s as corn hybrid seeds gradually became the choice of most farmers. By the 1950s, almost all farmers were using corn produced from hybrid seeds.

This is what happened, but why did farmers change after generations of tradition? Improved yields in the future were not guaranteed. The uniformity of hybrid fields made harvesting easier but these benefits were often not convincing. The most likely reason for the rapid spread of hybrid plants was the Dust Bowl experience from 1934 to 1936. The hybrid strains were clearly more resistant to drought than were the open-pollinated varieties [18].

During this time of transition and improving crop yields, there wasn’t any controversy about the ethics of the research or questions related to hybrid product safety. While scientists controlled the physical processes, the fundamental transformations were still regulated by natural forces. In a sense, nature had the final say as to what type of hybrid was produced. Nature protected itself. Then in 1953 James Watson and Francis Crick discovered the double-helix structure of DNA [19]. Francis Crick was quoted as saying, “We have discovered the secret of life” [20].

This statement was not completely accurate, but their discovery changed our view of genetics forever. DNA was actually first discovered in 1879 by the Swiss physician Friedrich Miescher [21]. Miescher recognized the unique biochemical properties but its connection to genetics slowly evolved over the 63 years before Watson and Crick’s structure discovery. Knowing how the amino acids were combined provided scientists with the framework to map the genetic structure of animal and plant life. They were able to develop specific, detailed genetic maps of certain plants and eventually, at the conclusion of a 13-year project, even the human genome [22].

Armed with the knowledge of plant genetic structures, scientists took some of the guesswork out of developing hybrids and shortened the developmental time. How? By altering the genetic structure directly without going through the traditional lengthy, imprecise cross-fertilization process. The practice of improving crops by subjective generational improvement was quickly an antique, at least to some farmers.

As you might expect, even with the new genetic manipulation tools, the successful development of genetically modified products still required a considerable amount of financial investment and risk. To protect that investment, companies relied on patent licensing both in the United States and internationally to recover their development expenses. This makes sense from a business perspective. After all, what incentive would a company have to invest $500 million on a new product if it could be copied by a competitor with legal immunity? The protection issue is straightforward for business process, device, and inorganic manufacturing. But what about patenting new life forms?

In 1972, Ananda Chakrabarty, working for the General Electric Company, filed a patent application entitled “Microorganisms Having Multiple Compatible Degradative Energy-Generating Plasmids and Preparation Thereof.” In other words, the patent assignee, General Electric, created and wanted to own a new life form. On March 31, 1981, the patent was approved [23] and legal precedent was set for the protection of genetically modified life forms, their precursors, and future generations. The companies that took the financial risk, created genetic innovations, and produced new products of value now had legal assurance that their investments were protected.

Armed with the genetic code and now favorable patent law, scientists developed methods to mask the expression of some genes and to insert new genes with desired traits that were not present in the host. An example of a genetic insertion from animal to plants occurred in the early 1990s by researchers at DNA Plant Technology Corporation [24]. They located a gene sequence in the Arctic flounder fish that coded for a protein that kept the fish’s blood from freezing. Scientists produced DNA based on the gene sequence and, after some changes, they transferred it to tomato plants. It was hoped that the genetically modified (or transgenic) tomatoes would have better freezing properties. The result? Nature: 1, Science: 0; it didn’t work. However, this was just the first inning of a game we are still playing.

What did work for tomatoes was a gene addition that prevented the production of an enzyme that produces rotting. The successful gene replacement enabled tomatoes to stay firm longer, basically increasing shelf life and resistance to physical bruising during harvesting. The U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) approved it as safe for public distribution in 1994 [25]. In spite of it being the first genetically modified food source, the FDA did not warrant special labeling since it saw no obvious health risk and the nutritional content and characteristics were the same as those of conventional tomatoes. The business failure after a few years of sales was attributed more to the company’s inexperience in food distribution than to the quality and viability of the transgenetic product [26]. Nevertheless, during the 1990s, the ability to change plant properties was firmly established and genetically engineered (GE) or genetically modified (GM) crops became used by a growing number of farmers.

In addition to the weather, weeds and insects are farmers’ major impediments to high yields so, on the surface, these “new and improved” hybrid crop variations seem like good ideas. Farmers operate on tight budgets and the ability to improve or just make crop yields more reliable is important for their sustainability. Also, with the world’s population growing to approximately 7 billion people, maximizing crop yields means more food for more people.

The plan was to have more reliable (and higher) crop yields, using fewer pesticides and herbicides. There are two major types of GM crops that are grown today: herbicide tolerant (HT), where plants are genetically modified to be resistant or immune to specific powerful herbicides, and “Bt”, short for the Bacillus thuringiensis, where the GM plants “naturally” produce their own pesticides to protect them from insects. The GM plants were also engineered to be resistant to common viruses, fungi, and other bacteria to make them more resilient and to allow them to thrive in a wide variety of soils with less care [27, 28]. The expectations also included crops that would be more resistant to cold, drought, salinity, and even nutrition. There has been some success in these noble goals. I think the proof is reflected in Figure 10.4, which shows the fraction of total acres planted with GM soybeans, corn, and cotton, the three largest agriculture products in the U.S [29].

Figure 10.4 U.S. growth of genetically engineered crops.

In 2010, over 90% of all soybeans, and over 60% of all corn, was produced from genetically modified seeds. Today farming is more of a science than ever before in history. So it makes sense as tractors today measure distances with onboard GPS equipment, farmers plant genetically modified seeds with pesticide and herbicide resistances that have taken the normal hybrid methods to new limits. It is also a good business model for the companies who supply the farmers. They perform the genetic research and periodically market new seed types with improved farming attributes. They additionally make the chemicals that the crops will require for treatment, and they own the second generation seeds since they, too, are covered in their patents. Farmers who plant GM crops are allowed only to sell their crops commercially. They also can’t store the seeds (unless they pay the licensing fee). Each year, they are required to buy the newest seed products and start the cycle all over again.

It’s almost like buying designer jeans. Every year, new styles are sold for basically the same type of clothes. Agribusiness has its own version of this model by marketing new seeds that promise better farming benefits. The difference here is that with clothes, once you pay the money, you own the jeans. With the GM seeds that isn’t what happens. The current state of the patent law as of 2010 says companies claim new seed types, their crops and subsequent seeds as their “invention.” Farmers can license use of the invention and pay the technology fees, but they don’t own the plants or the seeds. Imagine going to a store and paying money to license a new pair of jeans with the restrictions that only you can wear them (no hand-me-downs) and only for certain types of situations. This is basically what farmers must do who grow GM crops. See this chapter’s case study for further discussion.

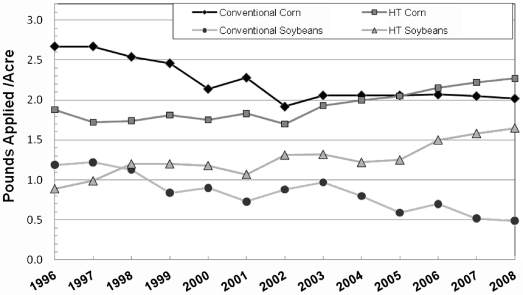

Well, agribusiness’ “business plan” appears to be have little risk from human threats but nature, apparently, is not accepting genetic modification as part of her plan. Figure 10.5 shows that pesticide use for GM corn and soybeans is now actually higher, on the average, than for the non-GM crops [30]. You might ask, “What has changed?” In simple terms, nature has adapted to the chemicals and developed its own “genetically modified weeds,” through natural selection, to survive in the new herbicidal environment. Recent research has confirmed the weeds are developing a strong resistance to the current herbicides [31]. In fact, the new version (or perhaps a better term) is the more recent generation of these weeds, called “super weeds,” which are fast growing and have thick stalks that can even damage harvesters [32]. So in the matter of a few years, weeds have evolved nearly just as quickly as the genetically modified plants and for now it appears that the weeds are gaining ground.

Figure 10.5 Average pesticide pounds applied per acre of conventional, herbicide-tolerant (HT), and Bt varieties, 1996–2008.

The United States has been the leader in developing and growing GM crops, although the Americans are not alone. The world’s leading producers of GM crops in addition to the United States are Argentina, Brazil, Canada, India, and China. Other countries that are beginning to do this type of farming are Paraguay, South Africa, Uruguay, Australia, Iran, and the Czech Republic. The European Union has resisted GM crops as a major food source [33].

There are pros and cons to GM crops and foods, with arguments related to everything from reducing world hunger on the proponent side to “playing God without knowing all of the rules” on the opposition side. This is a classic risk management scenario where uncertainty fuels the arguments of both sides. Here is an outline of the dominant issues on this very important subject. Keep in mind that it’s not an academic exercise—unless you don’t eat.

The proponents tout the benefits of better taste, higher quality, improved crop yields, better stress tolerance, and “friendly” biochemical herbicides and bioinsecticides; the list goes on. Some of these benefits are also seen in normal hybrid research, except the process takes longer. Also the ability to genetically modify a plant to contain specific properties by design in a relatively short time period has its appeal to agribusiness.

The business environment for the seed and agrichemical producers may be favorable thanks to the current interpretation of patent law. However, regardless of the legal issues’ morality or fairness, the intellectual property issues are trivial compared to the potential long-term health and safety questions that remain unanswered. To be fair, some proponents have answered these questions by saying that the science is in control and GM crops are good if not better than the natural varieties. Others are not convinced.

When genes are added, removed, or replaced in plants or animals for the purpose of developing new “products,” we judge the initial success directly from the expressed characteristics of the result. Are there unintended consequences? Proponents claim that testing before release ensures safety and this is the best we can do if we are going to continue to produce and consume GM foods. However, our functional knowledge of the human and plant genome is incomplete. We simply don’t know the potential human health effects from, for example, allergens, transfer of antibiotic resistance markers, unintended transfer of transgenes through cross-pollination, and unknown effects on other organisms such as soil microbes [34, 35]. Like most other areas of biology, the list of what we don’t know is a lot longer than the list of what we do know. So here we are, genetically modifying plants and animals in self-declared confidence when we can’t even predict the weather accurately 72 hours in the future. How are we then predicting food safety of genetically modified food elements for future generations? This is the risk. The benefits are a matter of continuous debate.

The issue of tampering with genes between species of plants and between animals and plants raises new questions that test our legacy standards. When you mix genes between species or between an animal and a plant, what do you call the result? Sure, it’s a hybrid, but the precise name that takes into consideration its genetic structure may be complicated. This is the situation of labeling of GM foods. The regulatory requirements for GM food labeling vary widely between countries.

In the United States, as of 2010, there was no requirement that genetically modified foods be labeled. This is perhaps a little strange since apple juice requires a label to show if it is made from concentrate or juice, and milk is labeled as homogenized or not, but plant or animal foods whose genetic structure has been modified require nothing.

In 2008, regulations were proposed that would not require producers to label most genetically engineered meat, poultry, or seafood. The rules treated altered DNA inserted into livestock as “drugs.” Companies are not required to alert consumers when antibiotics, hormones, or other drugs are used in animal development.

The FDA is making an exception in the case where genetic engineering alters the makeup of food. For example, companies are developing DNA that causes pigs to produce more omega-3 fatty acids in their muscles. In this case, the rules would require a label indicating the product is high in fatty acids, but not that it is genetically modified [36].

The U.S. government maintains this laissez faire, no labeling policy for genetically modified foods because:

1. Their analysis says there are no safety or health issues, and

2. The products are nutritionally equivalent to their nongenetically engineered counterparts.

Not everyone shares this view. In fact, there is a large grassroots effort to encourage food producers to voluntarily provide labeling. This sounds like a good idea, but voluntary labeling brings another set of problems. Every food producer can have its own terminology and definitions, so chances are that no two labels would have the same meaning. From the public’s perspective, you would know that some type of genetic engineering was involved but without strict labeling standards, the information would be hard to interpret.

Not all countries have the same view on GM food labeling as does the United States. For example, since 1997, the European Union has required labeling for food products that consist of or are derived from genetically modified organisms. Even genetically modified seeds must be labeled. The current version of this regulation (EC 1830/2003) [37] covers the traceability through the food chain and labeling of genetically modified organisms. It is clear that the European Union regulators believe that people should know about not just the ingredients, but also the genetic modifications that are deeply embedded in the food they eat. The labeling provides them a choice that is not widely available in the United States.

Other countries are at various stages of requiring GM food and feed labeling. As the world’s population continues to grow, the farming benefits of GM crops will continue to proliferate around the world. And let’s not forget that new life forms, that is, “products,” are being developed every year. We will learn either from science or time if genetically modified foods are as safe as the proponents claim, but in the meantime, in the spirit of personal risk management, everyone should at least have the right to know what they are eating.

ANIMAL PRODUCTION

Most animals destined for human consumption today are raised more in a factory than on a farm or ranch environment. One look at a typical supermarket meat section or fast food chain menu shows that there is no shortage of meat. And the prices are amazingly low considering the time, growing logistics, and transportation that are involved in getting the cows, chickens, turkeys, and ducks to restaurants and food stores. There is no magic here, only simple economics: the economics of scale.

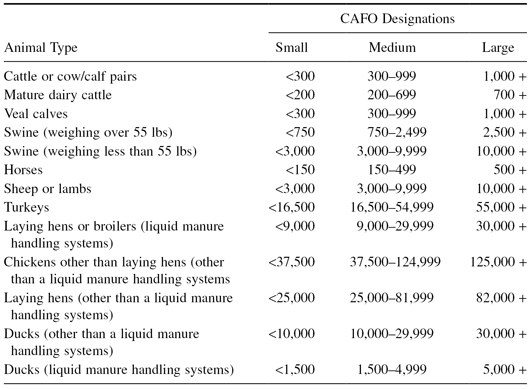

Production of this much meat at reasonable prices requires large-scale operations. These “factory farms” are called concentrated animal feeding operations (CAFOs). These facilities have the layout of a factory where animals are kept and raised in confined spaces. Feed is brought to the animals, and feces, urine, and other wastes are removed by specialized systems or processes. To give you an idea of the number of animals in these concentrated areas, Table 10.2 shows the animal counts required for a CAFO to be classified as small, medium, and large [38]. The EPA designates 19,149 U.S. farms as CAFOs. They also estimate that hundreds of thousands more facilities that confine animals (AFOs), not large enough to be classified as CAFOs, exist [39]. These meat production factories produce the bulk of the meat, poultry, and dairy consumed in the United States.

Table 10.2 CAFO Type and Animal Count Categories

From a risk management perspective there are benefits in the high animal concentration configuration to enable uniformity for applying growth hormones, regulating feed quality, and administering drugs. However, the same high animal concentrations require constant diligence to remove infected or otherwise diseased animals. Feed quality also becomes an important factor since all of the animals basically eat the same food at the same time. This was the root cause of the Salmonella enteritidis (SE) outbreak in the summer of 2010 [40].

A major practical issue associated with CAFOs is waste removal and processing. National and state governmental agencies monitor water quality and other variables to ensure the “emissions” are within the law [41]. With waste that is clearly identified chemically and by odor, violations do occur. Some are direct environmental infringements from unauthorized waste discharges with financial penalties. Others are violations of “Generally Accepted Agricultural Management Practices,” for example, spraying liquid manure on the 4th of July weekend is not a good neighbor relations tactic [42].

Given the current volume of meat production required to satisfy consumer demands, CAFOs and AFOs are technically efficient at providing our steaks, chicken, and hamburgers at reasonable prices. But there is a price. The Union of Concerned Scientists estimates that CAFOs leave staggering bills behind for taxpayers, including:

- $26 billion in reduced property values from odor and water contamination

- between $1.5 billion and $3 billion annually in drug-resistant illnesses attributed to the overuse of antibiotics in livestock production

- $4.1 billion in soil and groundwater contamination from animal manure leakage [43].

CAFOs and AFOs operate not as farms in the traditional sense but as low-tech chemical processing facilities whose product is meat. The literature is full of descriptions, video documentaries, and discussions about CAFOs and what they include in terms of the intense corn diet and antibiotic and other drug combinations that produce large animals in a short period of time. Obviously, this is good for business but at what price to our health? The food risk exposures are clear. Corn-fed, antibiotic-drugged, and growth hormone-laden livestock represent the bulk of our meat products today. The state and national agencies that inspect this intense industry do a good job most of the time with very few disease or animal product contamination outbreaks. The real risk is that no one really knows the long-term effects on humans of consuming such artificially treated food products and, just like with genetically modified seeds, only time will tell.

Rather than repeat what others have identified in terms of the risk exposures associated with these operations, l am taking you to a sustainable cattle farm where quality trumps quantity in an elegantly simple manner. I like to introduce you Betsy Ross.

Sometimes it takes an event completely out of our control to build something renewed. In the case of Betsy Ross, the birth of a premature grandson provided the incentive and drive to address issues in our food supply.

Ross believes she’s among the “last generation whose mamas knew where every bite they ate came from.” And while she herself moved out of that group during her career as a civil servant, at least when it comes to beef, she is back on the front lines.

Seeking the healthiest food for her new little one, Betsy Ross came back to the farm as a retiree to run cattle. Studying under the likes of Sally Fallon, Malcolm Beck, and Elaine Ingham, Ross came to realize that the soil itself was fundamental to the nutritional value of the animals raised on it.

“We were losing our shirts,” Ross said. “We were losing our grass to more and more weeds. Everything we were doing [to control the weeds] was unsuccessful.”

And so Ross continued her studies in the soil, taking classes within a national network of folks who sought to re-establish the healthy biology of the soil itself. Purchasing a $3,500 “tea brewer,” Ross soon began to recognize the benefits of reintroducing the natural organisms to the soil through composting and spraying the resulting organic “tea” on the pastures: “All of a sudden, the weights [of the cattle] were outstanding.”

At the time, Ross was one of just three women in her area of central Texas driving a tractor. “They called me the crazy lady with the green pastures.” And her results, in cattle weight, got the attention of her former “gurus.” The quality of her grass-fed cattle spoke for itself, and the student became the teacher. Ross began instructing prospective soil biologists, including those at Texas A&M University.

Ross runs her grass-fed beef farm as an organic farm. It’s labeled “grass-fed” rather than the even more restrictive term “organic,” as there is always the possibility that in a drought, the cattle will require a load of hay and organic hay may not be available. Better to forego the label than risk the cattle starve.

And Ross’ agenda remains with assuring the healthiest starting place for all she grows—and that is in the soil. She treats “pest” plants not as invaders in need of immediate chemical eradication but rather as indicators of the soil’s needs. Ross’ finely honed eye allows her to assess what’s growing unbidden and prescribe the appropriate enrichment for the soil that will make it less hospitable for the uninvited and, at the same time, more welcoming to the grass her cattle require. “If we just kill the weeds … we won’t know why they got there. And if you just get rid of it [without tending to the deficiencies of the soil] it just comes right back.”

Betsy’s sister and coworker Kathryn Chastant affirms the direction in which her sister leads. “We’re moving the land back to the way it was always done until after World War II when the chemical companies had to get rid of their nitrates.”

Just as Ross makes the best of the soil, she also seeks to raise the most productive grasses in each one’s time. For every season there is a grass. “It’s a matter of exploiting the opportunities nature presents,” she explains, speaking most simply about “one grass in dry weather, another that can withstand a freeze, and one yet that is very prolific each day the temperatures and water are available.”

Ross also employs a technique called “mob grazing.” Calculating the weight of food the herd needs each day, she positions the cattle into areas adequate for their grazing, then moves them throughout the day. While on the restricted patch of grass, the cattle eat, trample, and leave their waste products. In a short time, they consume much of what the small area has to meet their needs. Once moved, the area will be fallow for months. And within hours, dung beetles and other arthropods, fungi, and birds move in to pull down the manure left by the crowded herd. The residual returns to nourish the healthy soil. In addition, the short duration the herd spends on each patch of ground assures it not be hardened by trampling. As a result, the cattle incur many fewer shoulder problems. The softer ground also results in naturally polished and healthier hooves.

All in all, the Betsy Ross grass-fed beef enterprise is one that demands overall health, from the roots up. Quoting Chastant again, “We consider ourselves stewards of the land.” And theirs is a careful and masterful stewardship, resulting in a quality that may well be unsurpassed. One of their primary distributors is the rising star in food delivery, Whole Foods, of Austin, Texas.

No longer a start-up but in fact a leader and member of a number of standards organizations, Ross remains true to her own roots. For her standards are higher than those of the USDA and any organization to which she might belong. In Betsy Ross’ words, “My name is on every piece of meat. It can’t have [any flaws].”

No pesticides, no herbicides, incredible production through attention from the ground up, elegant, and effective: an anomaly in our world of chemicals, and a hope. This author’s hat is off to Betsy Ross. (More information about Betsy Ross’ cattle, grass-fed beef, and soil biology can be found at http://www.rossfarm.com/.)

DISTRIBUTION

Unless you are castaway on a deserted island, you probably don’t grow, catch, or harvest all of the food you eat. Someone else does these things. The food products are processed, stored, transported, and then stored again, waiting your purchase either at the food store, farmers’ market, or in your neighbor’s kitchen. In terms of the latter case, you’re probably free of the issues discussed here. But how many of us live that close to the people who make our food?

The primary risk exposure from this element of the food chain is contamination. Spoilage is number two but if something is spoiled then you don’t eat it. In the case of contamination, the food can look good, smell good, taste good, and can still kill you. In 2009–2010, the United States imported agricultural products from over 170 countries [44]. Among the fastest growing categories were live animals, wine/beer, fruit/vegetable juices, wheat, coffee, snack foods, and various seafood products [45]. This is a lot of food to check! Just to give a realistic example of the enormous size of the food inspection issue, consider the following. At the Arizona border checkpoint near Nogales, in the peak winter season, almost 1,000 produce trucks arrive daily, carrying eggplants, cucumbers, tomatoes, peppers and other products destined for your food markets. How can you be sure that the inspections process works? Well, you can’t.

Here again you see a situation where the potential for harm is great and the resources to protect us are finite. Food is imported through a wide variety of pathways and food safety inspection resources are no match for the volume, diversity, and geographical distribution of entry points.

In 1997, during the Clinton Administration, a risk-based set of preventive controls known as Hazard Analysis and Critical Control Points (HACCP) was introduced. These procedures focus inspection efforts on the bottle necks (or critical control points) in the food chain. The method was actually created by NASA and the Pillsbury Corporation in the 1960s for food protection during human spaceflights [46]. The HACCP method has 7 basic steps.

1. Identify the hazards

2. Determine the control points and the critical control points

3. Set critical control limits

4. Monitor critical limits

5. Take corrective action when limits are exceeded

6. Establish an effective recoding system

7. Verify the system is working as planned.

The method’s philosophy is that if food is checked at its major processing points, that is, storage, defrosting, and cooking, then contamination can be identified and specific corrective actions can be taken early to minimize severity.

The government at the time used HACCP as a deregulation tool that allowed food manufacturers to do the critical point inspections themselves rather than through government inspectors. It also basically standardized food handling and food processing best practices in many different types of facilities. Regardless of the politics, the method is an important risk management tool being applied today internationally in a wide range of food production industries, including restaurants.

With food imports’ growing diversity, the HACCP approach is not reliable by itself as new regions and food products enter the marketplace. The data speaks for itself. Approximately 76 million food-borne illnesses occur annually in the United States involving more than 300,000 hospitalizations and 5,000 deaths [47]. These numbers appear large but let’s look at the exposure base. Assuming there are 300 million people in the United States and everyone eats three meals a day for 365 days, there are to 328.5 billion meals consumed each year. Dividing 76 million by this number estimates the probability of obtaining a food-borne illness per meal per person as 0.0002. This is a small number so your chances of getting sick from contaminated food are low, yet from a societal point of view, 76 million food poisoning illnesses is unacceptable.

It is clear that the HACCP method and other food safety measures are not working as well as required. Even though a risk-based process was being used, it had become static. Congress asked the Institute of Medicine (IOM), a nongovernmental organization under the National Academy of Science, to examine the gaps in the FDA’s food safety systems since it oversees the majority (about 80%) of U.S. food supply. Their findings commended the FDA in their risk assessment approach to food safety but also said that it was not enough. They claim the present system is reactive and places too much emphasis on case-by-case analysis. The IOM recommends the FDA adopt an enhanced risk-based approach to food safety including:

- Strategic planning with performance metrics

- Public health hazard risk ranking

- Targeted information collection

- Situation analysis and intervention planning, and

- Ongoing measurement and program reviews.

The report contains the details but there are some interesting aspects of the recommendations that warrant a mention here. Often, the adoption of a risk management approach to a business or activity is viewed as primarily a change of behavior of the current workforce. Risk management can be taught, but that takes time. Their recommendation included training employees but also hiring new personnel with risk management and analytical expertise. They also identified shortcomings in the FDA’s ability to collect, analyze, interpret, manage, and share data. These functions are essential for any effective risk management program.

Food safety is a complicated process in the United States, with state agencies responsible for intrastate commerce and the federal government, state, and local agencies all sharing the responsibility for interstate food commerce. The IOM’s report also highlights the need for agency policy and procedural integration to ensure effective risk communication and food safety education. And, of course, since you can’t change government actions without changing the laws, the report also includes a recommendation to modernize food safety laws. All of this translates to a major overhaul of a food safety system that may have worked well in previous decades, but, as of 2011, is out of date [47].

The FDA may not agree with the “out of date” part. More resources are being applied, and risk management is still the primary methodology. The FDA employs a risk-based method to identify high risk food establishments for its domestic and foreign food inspections. High risk food establishments are growers/harvesters, manufacturers/processors, packers, repackers, and holders of “high risk foods,” that is, those foods that can present hazards which the FDA believes, based on scientific evidence, can pose a high potential to cause harm from their consumption [48].

High risk food commodities include, but are not limited to, modified atmosphere packaged products; acidified and low-acid canned foods; seafood; custard-filled bakery products; dairy products including soft, semisoft, and soft ripened cheese and cheese products; unpasteurized juices; sprouts; ready-to-eat fresh fruits; fresh vegetables; processed fruits; processed vegetables; spices; shelled eggs; sandwiches; prepared salads; infant formula; and medical foods. This list is not inclusive because the identification of high risk food establishments is dynamic and subject to change in response to new information. For example, in recent years, FDA has identified high risk food establishments as those that include products whose formulations do not include an allergenic ingredient but, because the products are made in a firm that also makes allergen-containing foods, may inadvertently contain an allergen which is not declared on the label. Common allergenic substances include milk, eggs, fish, crustaceans, tree nuts, peanuts, and soybeans.

In the complex multiagency bureaucracy that manages food safety, there is always room for improvement and changes are being, and will continue to be, made. Risk management is fundamental to the current and future food safety strategies, programs, and activities. As to whether the current system is adequate, let’s extend the food poisoning probability calculations and see if you keep your appetite.

With a probability of 0.0002 (2.0 × 10−4) to obtain a food-borne illness per meal per person, let’s factor in how many meals you eat in a year. If you eat (3 × 365) meals per year, then your probability of food poisoning per year is 0.25 or 25%. You can decide for yourself if this current level of safety is acceptable or not. It is now appropriate to discuss the most important element of the food chain.

CONSUMPTION

Food poisoning is not the flu but it is defined as a flu-like illness typically characterized by nausea, vomiting, and diarrhea, due to something the victim ate or drank that contained noxious bacteria, viruses, parasites, metals, or toxins [49]. Approximately every second of every day, two people in the United States are stricken, and about 100 people die each week from food poisoning. These numbers probably underestimate the actual magnitude of the problem since doctors see only a small portion of the food-related illnesses. Many people with food poisoning assume they have a stomach bug (or the flu) and never visit the doctor. The costs? When tallied up in the United States, the consequences of foodborne illness including doctor visits, medication, lost work days, and pain and suffering amount to an estimated $152 billion annually [50]. Other researchers have cost estimates ranging from $357 billion to $1.4 trillion [51].

You can get food poisoning from eating the “wrong” type of mushrooms, the wrong parts of some fish, or food tainted with parasites. But the majority comes from eating food contaminated with different kinds of bacteria. The major pathogens are

1. Salmonella

2. Campylobacter

3. Shigella

4. STEC O157

5. STEC non-O157

6. Vibrio

7. Listeria

8. Yersinia

Even if you’re not a microbiologist, you probably recognize at least one of these names, perhaps from personal experience or from media coverage of food poisoning outbreaks around the country or world. Others may be less well-known but they all are major elements of our food risk that warrant our attention and understanding. The more you know about these risks, the more you can do to prevent getting sick or worse.

Salmonella [52] causes more food-borne illness than any other pathogen. It is a genus of bacteria with similar structural characteristics that live in the intestinal tracts of humans and other animals, including birds. Reptiles are particularly likely to harbor the bacteria. Animals can have the bacteria without getting sick. It is not paranoid to have anyone, especially children, wash their hands after handling a bird or reptile. The primary transmission pathway to humans is though foods contaminated with animal feces and it only takes a small, imperceptible amount to contract the illness.

For some contamination pathways, we have little control over the risk. For example, the Salmonella outbreak in the summer of 2010 that forced the recall of 500 million eggs was caused by Salmonella-contaminated grain fed to chickens at several large egg-producing chicken farms [53]. How can you be sure the eggs you eat are safe? The answer: raise your own chickens. And then, do so carefully.

The good news is that thorough cooking kills Salmonella, but food may also become contaminated by an infected food handler who did not wash his or her hands with soap after using the bathroom, or from someone who handles raw eggs or meat and immediately afterward doesn’t wash his or her hands or clean the work area before continuing meal preparation.

Campylobacter is also one of the most common causes of bacterial food-borne illness in the world [54]. It is found in a variety of healthy domestic and wild animals including cattle, sheep, goats, pigs, chickens, dogs, and cats. It usually lives in the intestines as part of the normal flora and is shed in feces. The bacteria can live in water troughs, stock ponds, lakes, creeks, streams, and even mud.

Because Campylobacter can exist in many parts of the environment, food products (especially poultry, beef, and pork) are at risk of contamination during processing. It is readily destroyed by pasteurization of dairy products and adequate cooking of meat products. As in the case of Salmonella, a major risk exposure to humans is cross-contamination in the preparation of food by not washing hands or sanitizing work areas after handling raw meat and other uncooked food components. An additional risk exposure for people who contract this intestinal infection is the rare occurrence of Guillain-Barré syndrome, an autoimmune condition that attacks the nervous system. Recent research has shown that exposure to the Campylobacter infection can cause this serious secondary illness [55].

Shigella is a genus of bacteria that can cause sudden and severe diarrhea. It can occur after ingestion of fewer than 100 bacteria [56], making Shigella one of the most communicable and severe forms of bacterial-induced diarrhea. The bacteria thrive in the human intestine and are commonly spread both through food and by person-to-person contact. For example, toddlers who are not completely toilet-trained can infect people they contact, people of all ages playing in public untreated shallow water areas such as fountains are at risk, and other potential sources include flies that migrate from infected sites to people and inadequately washed vegetables.

STEC O157 is an abbreviation for “Shiga toxin-producing” Escherichia coli. First of all, E. coli is a large and diverse group of bacteria, and most strains are harmless. Others can make you very sick with diarrhea, urinary tract infections, respiratory illnesses, and other illnesses. Biologically, we need E. coli to maintain the delicate chemical balance of our intestines. It’s when the bacteria change slightly, or mutate, and have vastly different properties, that the problems begin.

The most common STEC O157 mutant in North America is O157:H7, found specifically in the intestinal tract of cattle. This strain of the Escherichia bacteria, discovered in 1982, was known then to cause sickness in humans but its food risk importance was not recognized for another 11 years. In 1993, after a fast-food outbreak that sickened more than 700 people and killed at least four children, both the media and food safety professionals began to treat this bacteria strain as a serious public health threat.

The bacteria’s name is actually written in a detailed code. The alphanumeric labeling, in a sense, is like the bacteria’s social security number, except that it refers to unique aspects of its structure. The O157 refers to a particular surface antigen marker on the outer surface of the cell. The H7 is another antigen that is located on the cell’s pilae or hair-like structures. These two markers identify the particular strain of the E. coli bacteria. Today several new strains have been identified [57], some of which will be mentioned in the STEC non-O157 discussion.

STEC O157 has the same contamination path as the other pathogens: your mouth. You either eat contaminated food or pass small, invisible amounts of human or animal feces from your hands to your mouth. You can get infected by swallowing lake water while swimming, touching the environment in petting zoos and other animal exhibits, and by eating food picked or prepared by people who did not wash their hands well after using the toilet. The risk mitigation actions of washing your hands, not swallowing lake or stream water, and knowing what you eat at restaurants sound pretty easy. They are—but don’t mistake simplicity for insignificance. The stakes are very high. STEC O157 infections are serious conditions by themselves, but the stress on other organs can induce hemorrhagic colitis and hemolytic uremic syndrome, requiring blood transfusion and kidney dialysis.

To minimize your risk exposure, stay away from unpasteurized (raw) milk, unpasteurized apple cider, and soft cheeses made from raw milk. If you work with cattle, then keeping your hands away from your face is a “no brainer,” but other risk exposures like eating undercooked hamburgers or contaminated but seemingly “fresh” vegetables can be more difficult to detect.

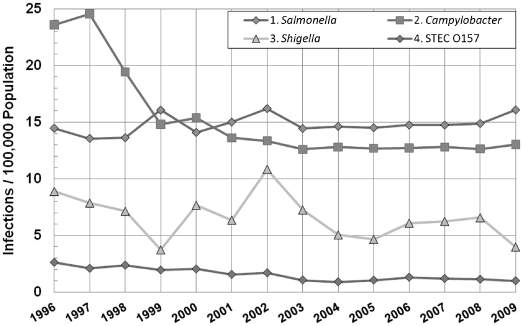

The bacteria infection agents I’ve mentioned so far—Salmonella, Campylobacter, Shigella, and STEC O157—are the major food risk exposures we share each day. We hear about the major outbreaks, the sickness, and sometimes tragic deaths but the magnitude to the risk exposure is not adequately represented by sporadic news events. The risk exposures and the human suffering from these food-related illnesses are continuous. Figure 10.6 shows the frequency of occurrence of the four top food-borne pathogens in the United States from 1996 to 2009 [58]. The vertical axis is the number of infection cases per 100,000 people. The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention also publish national health objective targets for three of the four pathogens shown here. How these targets are selected is a subject for another book. However, to show you how the United States is actually managing our national food safety risk, the target for Salmonella is 6.80; the 2009 result was 15.19. The target for Campylobacter is 12.30; the 2009 result was 13.02. The target for STEC O157 is 1.00; the 2009 results were 0.99. As of 2010, no national health objective has been set for Shigella.

Figure 10.6 Part one: top eight food infections, United States, 1996–2009.

The next four pathogens have lower infection frequencies but are still major risk exposures. We begin with STEC non-O157. Shiga toxin-producing E. coli identification is usually done through lab testing of stool specimens. For STEC O157 strains, there are common diagnostic protocols, standards, and testing facilities, but the same cannot be said for STEC non-O157 bacteria. The testing procedures require different training and equipment and as of 2010, there are no clear guidelines for reporting, testing, and interpretation of results. Most labs can determine if an STEC is present and can identify E. coli O157 but to determine the O group of non-O157 STEC, strains must be sent to a state public health laboratory.

The six most common strains of non-O157 E. coli are O26, O45, O103, O111, O121, and O145. All of these relatively new pathogens have a track record of causing food poisoning outbreaks. Researchers believe that risk mitigation practices are the same as for the STEC O157, strains which is the good news. The food risk exposure lesson here is that basic tenets of good hygiene and food preparation practices are the best defense against this ever-changing bacteria offense.

Vibrio is a genus of bacteria that requires the salt environment of sea water for growth, so it is limited to seafood. Vibrio is also very sensitive to temperature and proper storage below 40°F, and sustained cooking above 140°F, will kill the bacteria. This bacteria can be problematic for countries where the diet consists primarily of seafood, for example, Japan (and any sashimi serving for that matter), where seafood is often consumed raw.

The Listeria [59] genus of bacteria is widespread in nature. L. monocytogenes is the particular strain that has caused the most illness although, evidently, not all humans are susceptible. Research has shown that this strain may actually exist in the intestines of 1%–10% of humans with no ill effects. It has also been identified in 37 species of domestic and feral mammals, at least 17 species of birds, and in some species of fish and shellfish [60].

What makes L. monocytogenes so dangerous is its resiliency. It can grow in refrigerated temperatures as low as 37°F, and also survive temperatures of 170°F for a short time. The bacteria’s most favorable growth conditions are moist areas such as around drains and air conditioning vents that develop condensate.

Despite the small number of cases reported each year, the mortality rate (20%) is relatively high. Pregnant women and their fetuses are the most susceptible to severe illness and death. The CDC reports that pregnant women are 20 times more likely to become infected than nonpregnant healthy adults [61].

Last, but not least, in the list is the Yersinia bacteria family. In the United States, most sickness is caused by one particular strain called Y. enterocolitica. The bacteria can be found in pigs, rodents, rabbits, sheep, cattle, horses, dogs, and cats. Humans can get sick from eating contaminated food, especially raw or undercooked pork products [62]. The abdominal pain and diarrhea usually lasts from 1 to 3 weeks. While the symptoms are unpleasant, the bacteria doesn’t have the life-threatening potential compared the others previously mentioned.

Figure 10.7 shows the infection rate for last four bacteria families in our list. What is particularly noteworthy about this plot are that apparent trends. Since the y-axis is computed in terms of the number of infections per 100,000 people, population growth by itself is not a factor here. Notice that the infection rates for Listeria, Vibrio, and Yersinia have converged and stabilized at about 0.35 infections per 100,000 people. However, the infection rate for STEC non-O157 bacteria has roughly increased 300% from its 2001–2002 level. Shiga-producing toxin E. coli may be increasing in nature, diagnostic technology may be improving, there may be a growing awareness of the toxicity and nature of non-O157 strains, or all of these factors may have contributed to the sharp increase. The increase has been noted by the USDA’s new food safety chief, Elisabeth Hagen, and additional regulations for beef processors are being planned to change the infection trend shown in Figure 10.7 [63].

Figure 10.7 Part two: top eight food infections, United States, 1996–2009.

However, regulations are not a guarantee that any of these eight major bacteria groups discussed here will not enter the public food supply. For right now and for the foreseeable future, it is safe to say that food safety represents, and will represent, a significant societal and personal risk exposure.

Your food safety risk management should engage both your mind and your senses. Pay attention to the sanitation conditions of the restaurants where you eat out and in the stores and markets where you buy food. Pay attention to the temperature, color, aroma, texture, and taste of the food you buy, cook, and eat. Unless you grow and cook all of your own food and watch your own food-handling habits, there is no guarantee that you won’t become a food poisoning victim even if do all of the right things.

And from this section on, your view of bathroom hygiene should take on a new level of cause and effect importance. For example, why do restroom doors only have handles on the inside, requiring you to touch the handle of the door to leave? Shouldn’t it be the other way around?

HEALTH

The last element of the food chain is “where the rubber meets the road,” or perhaps a better metaphor is “where the food meets your mouth.” At supermarkets, convenience stores, or restaurants you choose what you are going to eat. Here’s where your tastes, education, training, intellect, and yes, survival instincts come into play. It might be unfair to say that “you are what you eat” but then again, maybe not. Take, for example, the amount of fruits and vegetables you consume on a daily basis. Sure, it’s common knowledge that a healthy diet consists of several portions of these foods daily. But for you agnostics or ambivalent believers, recent research makes a very compelling argument. Here’s a brief description of several research projects.

- An analysis compared studies involving 257,551 individuals with an average follow-up duration of 13 years. The results were based on the observed health characteristics of those individuals who ate fewer than three daily servings of fruit and vegetables. For participants who ate three to five servings, the stroke risk was reduced 11%. For those who ate more than five daily servings, stroke risk was reduced 26% [64].

- An analysis of several studies that observed the diets and health of 90,513 men and 141,536 women showed for each daily serving of fruit, stroke risk was reduced by 11%. Additional vegetable daily servings only decreased stroke risk by 3% [65].

- In a study of 72,113 women over eighteen years, those individuals whose diets consisted of more fruits, vegetables, legumes, fish, and whole grains had a 28% lower risk of cardiovascular disease and a 17% overall lower mortality risk [66].

- In a Harvard study of 91,058 men and 245,186 women, for every 10 grams of fiber consumed daily by the participants, there was a 14% decrease in heart attack risk and a 27% decrease in fatal coronary heart disease [67].

- A study of over 300,000 people in eight different European countries showed a 4% risk reduction in heart attacks caused by reduced blood supply problems for each portion of fruits and vegetables above two daily servings [68].

The large study group sizes and result consistency presents a very convincing case that it is definitely worth your time to take your diet more seriously. These studies are also interesting in that they provide a sliding scale for stroke and heart risk as a function of the daily amount of fruits and vegetables consumed. You can choose your risk reduction by the number of daily servings you decide to eat. From reading the details of these studies, it appears to me that “You ‘are’ (to some extent because of) what you eat.”

With fruits and vegetables you can see their differences. Asparagus doesn’t look like broccoli, and apples are easily distinguished from bananas. For these food groups, we can look, touch, smell, and squeeze the products before we eat them. Have you ever done this at a food store and, based on some negative feedback, decided not to buy the item?

But not all food can be examined this way. Sure we can (and should) examine the food for contamination characteristics but now it’s time to use a more intellectual approach: READ THE LABELS.

Food labeling is a mixture of science, art, and politics. The science is the easiest part. Each term used on a label has a specific meaning. Once you know the language, like the meaning of the various types of fats, sugars, preservatives, oils, and alcohols, just to name a few things, you’re in pretty good shape. Based on the creativity of some new courses offered in higher education, I am surprised that colleges don’t have courses on food label chemistry or “how to read food labels” since everyone has a vested interest in the subject. The art form refers to what is said and shown graphically on the label, how the words and pictures are perceived and what they really mean. Food labeling content, word size, and even position are regulated in most countries. The laws appear strict when you read them but in reality, there’s plenty of wiggle room for producers to present an image that’s not totally accurate.

The laws require the caloric value, fat intake, and nutrient contents per serving. In addition to these items, labels will tell you all of the ingredients, including preservatives, and the relative amounts of each. But does the nutrient and ingredient data really describe what’s inside the package? Let’s do an experiment.

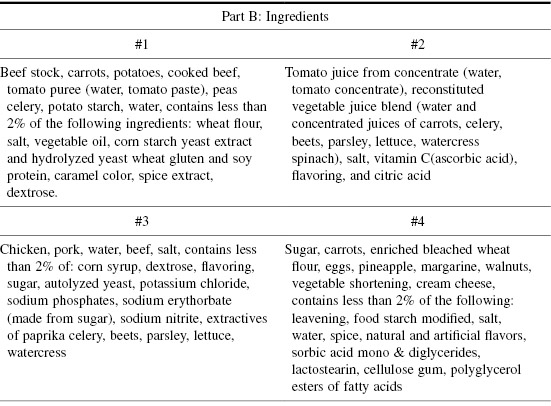

In Table 10.3, there are four label descriptions I’ve taken from common foods, and their four sets of ingredients. The information on these labels is impressive. But, is it useful? First, see if you can match the following nutrient descriptions to the ingredients. Then identify the food each set describes. The answers are at the end of the chapter.

Table 10.3 Food Labels: What Are the Foods?

Do you think we could invent a new kind of trivia game here?

In addition to the chemical contents and ingredients, products that have been irradiated contain a radura, the international symbol for irradiation, and must display the notice: “treated by irradiation” or “treated with radiation” on their packages. Consumer products that include irradiated ingredients like spices do not require any special labeling.

Here’s how this radiation process works. Food is passed through an electron, x-ray, or gamma ray field for various durations, depending on the type of product, and never comes in direct contact with the radiation source. The radiation kills bacteria and other food borne pathogens like Salmonella, E. coli O157:H7, Campylobacter, and others, with a minimal loss of nutrients. There are some new chemical compounds formed called “radiolytic” products that are common in glucose, formic acid, and, after very extensive research, nothing has been found that poses any harm to the consumer.

Today, food irradiation is used in more than 40 countries to help reduce food contamination risks. Even though NASA has fed irradiated food to its astronauts since the Apollo 17 moon mission in 1972, there still is a concern about the safety of preserving food through radiation when it will be consumed by the general public.

Introducing the U.S. general public to irradiated food has been compared, by some public health analysts, to the controversy that arose before the initiation of pasteurization in the early 1900s. The same concerns for loss of nutrient value, formation of harmful byproducts, and taste changes were seen. However, widespread public acceptance has been hindered by the radiation exposure’s perceived danger [69].

Probably the most used and abused word on labels is “natural” or, in some cases, “100% natural.” You see it on food products which are trying to appeal to the logic of “If it is natural, it must be good for you.” Well, mercury, lead, arsenic, and uranium are all from nature, as well as hemlock, but I have yet to see these natural elements as part of our dietary requirements. On actual product labels, the ingredients may have natural ingredients such as apples, raisins, carrots, and oats, but if you look closely at the list you might also see very unnatural ingredients such as partially hydrogenated oils or high fructose corn syrup (HFCS). So the word is meaningless, but it is great marketing.

The FDA is starting to address the definition of “natural” in food labeling by stating that HFCS does not qualify for the “natural” label. The official statement by the FDA on their website is:

From a food science perspective, it is difficult to define a food product that is “natural” because the food has probably been processed and is no longer the product of the earth. That said, FDA has not developed a definition for u se of the term natural or its derivatives. However, the agency has not objected to the use of the term if the food does not contain added color, artificial flavors, or synthetic substances. [70]

So the government provides us general guidance and the individual players are left on their own to work out the details. For example, the Corn Refiners Association trade group claims that HFCS is derived from corn, so it is a natural sweetener. On the other side of the issue are the Sugar Association and consumer groups such as the Center for Science in the Public Interest. In 2007, both Cadbury Schweppes and Kraft decided to remove "natural" labels from their products containing HFCS. Why? They were threatened with lawsuits [71]. The FDA’s lack of specificity on this issue creates legal and market risk exposures where the rule of law is settled by lawyers. This is one example but generally speaking, the FDA has been selective in setting food labeling policy.

As mentioned in the previous section, mandatory labeling of genetically modified foods has been proposed in the United States, but nothing has been done by Congress. The European Union requires labeling and has been resistant to even the marketing of genetically modified food in the region. Some products are approved [72, 73] but generally the Europeans have a different view of genetically engineered foods than the U.S. Congress and the food industry. To give you a perspective of the extent to which genetically modified have penetrated U.S. food products, it has been estimated that about 75% of processed food on supermarket shelves, such as soda, soup, and crackers, contain genetically engineered ingredients [74]. If Congress required genetically engineered food labels, I think we would be surprised to learn the true effect this technology has on the food we eat.

While the United States does not require labels on genetically modified foods, there are very strict regulations and operational guidelines for foods that have the “organic” label. This is one label that means what is says: only natural fertilizers, no pesticides, no herbicides, no animal antibiotics, and no animal growth hormones. In many ways, organic farms are sustainable ecosystems compared to the food factory practices of CAFOs and related farms. Organic certification is an ongoing process and the rigorous certification process helps maintain a respected level of credibility.

There are however, variations in “organic” labeling that you should know about. The first two categories are permitted to display the unique USDA Organic seal.

- “100% organic” labeling means just that. All of the ingredients qualify to be organic by the previously mentioned criteria.

- “Organic” on the label by itself signifies that at least 95% of the ingredients are organic.

- “Made with organic ingredients” means that at least 70% of the ingredients are organic.