The routes of the ancient Silk Road travel through more than a dozen countries between China and the Mediterranean, crossing some of the most challenging and inaccessible regions on earth. In classical times, the arid deserts and freezing mountains were incredibly hazardous to the long-distance travellers, who hastened to their journeys’ end, pausing to rest only in the oases that had grown up along the way. Today, travelling the modern Silk Road, conditions are infinitely easier and more pleasant. The same fertile and hospitable oases remain, but the route between them is so greatly improved that the traveller is free to marvel at the natural beauty of endless, shifting sand dunes and serried, snow-capped mountains without fear of death through starvation, thirst, frostbite or attack by bandits (though modern hazards, notably motor accidents, may still pose a threat).

A camel silhouetted at sunrise.

Getty Images

A Kyrgyz family by Karakuli Lake.

Getty Images

The highway from Xi’an

The Silk Road starts life in the great city of Xi’an, formerly Chang’an, a modern metropolis, capital of China’s Shaanxi Province, and home of the extraordinary Terracotta Army. From here, National Highway 312 and the railway trace the old route west to Lanzhou, capital of Gansu province and the largest city in northwest China. Lying in a gorge, hemmed in by steep mountains, its strategic location has long made it an important garrison town. Surging through its centre is the Huang He, coloured a rich chocolate by the huge quantities of loess it carries downstream.

It took 20 days to travel the first stretch of the journey from Xi’an to Lanzhou by pony, which until the 1930s was the only way to go. Today, by coach or train, it takes eight hours.

Beyond Lanzhou the route continues through the long, narrow Hexi Corridor in some of the most dramatic terrain in all of China. Extending for about 1,000km (620 miles) to Yumen near the frontiers of Xinjiang, China’s westernmost province, this unwelcoming landscape is punctuated by fertile oases that form the basis for such old Silk Road towns as Wuwei, Zhangye and Jiuquan. To the north stretch the barren wastes of the Gobi desert, and to the south the permanently snow-covered peaks of the Qilian Mountains. They mark the northern rim of the great Tibetan plateau, product of the cataclysmic collision between India and Asia some 200 million years ago – a process that continues today, as the Indian plate presses into the Asian land mass at the rate of about 20mm (0.8in) every year.

“There are among them venomous dragons, which spit forth poisonous winds, and cause showers of snow and storms of sand and gravel. Not one in 10,000 of those who meet these dangers escapes with his life.” Faxian (5th-century Buddhist) on the Pamirs

The limits of China “proper”

Following the Old Silk Road, National Highway 312 is paralleled by the Lanxin Railway, and now carves its way west between these deserts and mountains, through a region that for centuries was seen by the Chinese as the limits of civilisation. Beyond Jiayuguan was alien territory, the home of wandering desert ghosts and fierce nomads, a land bitterly cold in winter and intolerably hot in summer, where a lack of water meant only a few hardy plants such as the desert tamarisk and sagebrush could survive. Journeying along any section of the Silk Road was an epic undertaking: merchants spent months or even years waiting for the season to change or a war to end. Men couldn’t travel faster than their feet, horse or camel could carry them, and steppe and mountains slowed their progress, forcing them to find navigable passes, food and watering holes.The oasis of Dunhuang, in Gansu Province, is the site of some of the greatest Silk Road discoveries. It marks the limits of China “proper” and the start of Central Asia, and is also where the route presents its first major division, offering three ways forward.

Seeing the sights on camelback at Bezeklik Thousand Buddha Caves in China.

Getty Images

Highway 312 takes the Northern route, signposted with the ancient beacon tower at Yumenguan and heading for the oasis of Hami. The old Central Route goes via Loulan and a howling wilderness, the Desert of Lop, vividly described by Marco Polo. This route was abandoned more than 1,500 years ago and until 1996 China tested its nuclear bombs here. The third, Southern Silk Road heads southwest from the crumbling beacon tower of Yangguan, across the arid wastes of the Kum Tagh “Sand Mountains”, home to China’s only wild camel reserve.

The Chinese authorities are rapidly changing the ethnic map of their great western province of Xinjiang, the “New Frontier”, allowing Han Chinese migrants to stream into the province where they now dominate Urumqi and the Dzungarian Basin in the north. But in the south, Uighur Turks and other related Turkic peoples are still predominant in many of the oasis towns that are strung like green jewels around the northern and southern rims of the Tarim Basin. On foot or by camel, the journey from Urumqi to Kashgar used to take about three months through the deserts of northwestern China. Men and camels died of thirst, lost among the dunes. When the railway arrived in the 1960s: the journey time fell to 24 hours. Today the flight time is 45 minutes. This is impressive country, centred on China’s largest desert, the incomparable Taklamakan (see box).

The Taklamakan

Of all the obstacles to progress along the Silk Road, the most fearsome was the Taklamakan desert. Its very name, Takla makan, means: “Go in and you will never come out”. At 1,000km (620 miles) long and 400km (250 miles) wide, covering 270,000 sq km (105,000 sq miles), it is one of the world’s largest sandy deserts.

The Taklamakan was a serious hindrance during the height of the Silk Road and it remains a perilous wilderness. The great Swedish explorer Sven Hedin (1865–1952) was nearly one of its victims when he spent two desperate weeks trudging through the sand only to realise he had been going round in circles. He was reduced to drinking camel urine and only had the energy to crawl on all fours towards the forested edge of the desert. Two human companions and all but one camel died.

Winter temperatures can plunge to −20°C (−4°F). In 2008, snow was recorded right across the desert, reaching a depth of around 4 centimetres (1.6 in). With howling winds and desert ghosts, it is almost completely waterless, and comparable in terms of both harshness and beauty to Arabia’s Rub’ al-Khali or “Empty Quarter”. Utterly uninhabited, the centre of the Taklamakan is filled with huge, shifting dunes, and it was only recently penetrated by two cross-desert highways built by the Chinese in their search for oil.

Over the roof of the world

The Northern and Southern Silk Roads reunite at the old caravan city of Kashgar before climbing into the once-impenetrable Pamir Knot and leaving China via three routes. For centuries this transitional region marked the point where Chinese influence ended and the Silk Road passed into western Central Asia. The most dramatic of these routes is the Karakoram Highway, a Chinese-built metalled road leading south and over the Khunjerab Pass (4,693 metres/15,397ft) to Pakistan. This is the highest paved international road in the world, and it descends through the awe-inspiring scenery of the Hunza Valley and within reach of Baltistan, home to five peaks in excess of 8,000 metres (26,000ft), including the world’s second-highest peak, K2, and some of the world’s longest glaciers.

A snowy section of Karakoram Highway in Xinjiang, China.

iStock

Two other roads head north and west from Kashgar, going via the Irkeshtam and Torugart Passes respectively, to neighbouring Kyrgyzstan. At 3,752 metres (12,310ft), the Torugart Pass through the Tian Shan is lower than the Khunjerab, but the road is narrow and difficult, often being blocked by heavy snow and avalanches. The easiest pass is the Irkeshtam, rising to 2,841 metres (9,321ft) before descending, via a narrow mountain valley, to the Kyrgyz city of Osh and the fertile Fergana Valley, most of which lies today within Uzbekistan. This is the heart of the Central Asian region known in antiquity as Transoxiana – the region beyond the Oxus River. In fact the region is watered by two great rivers, the Oxus and the Jaxartes, which the Uzbeks call the Amu Darya and Syr Darya. To the north lies the endless steppe of Kazakhstan, and to the south the jagged peaks of Afghanistan’s Hindu Kush mountains, crossed by the army of Alexander the Great in 326 BC.

In classical times a branch of the Silk Road passed south of the Oxus, through the sandy wastes of northern Afghanistan, past the fabled city of Balkh – now little more than ruins – and Mazar-e-Sharif, the principal city of northern Afghanistan, before turning south to Herat and on to the great northeast Iranian city of Mashhad. There was another route to the north, via the Dzungarian Gate between northern Xinjiang and Kazakhstan, that avoided the Pamirs, but at the cost of travelling far to the north through territory controlled by fierce nomads.

Sunset over Bukhara’s Kalon Mosque and Minaret.

Getty Images

So the main route continued west from Osh, through the settled Fergana Valley and the cities of Andijan and Kokand, to the former Sogdian centre of Chach – today the largely concrete city of Tashkent, the capital of Uzbekistan and the largest city in Central Asia.

From Tashkent the main branch of the Silk Road continued southwest, passing through the narrow defile called the “Iron Gates” in the Buzgala Gorge and on to the fabled Silk Road cities of Samarkand and Bukhara. Beyond Bukhara the old Silk Road left the banks of the Zerafshan River, crossing the Oxus near Chardzhou – now the city of Turkmenabat in Turkmenistan – and continuing over the black sands of the Karakum Desert to the old oasis city of Merv on the desert’s southern edge. The Arab historian al-Muqaddasi, writing in the 10th century, described Merv as “delightful, fine, elegant, brilliant, extensive, and pleasant”, but only the evocative ruins of the ancient city remain today.

Balkh in northern Afghanistan is one of the oldest Silk Road cities and is considered to be the first settlement to which the Indo-Aryan tribes moved from north of the Oxus River between 3,500 and 4,000 years ago.

Persia and the Arab heartlands

Merv was where the southern spur of the Silk Road running through Balkh rejoined the main route. Beyond it, the route led southwest across the modern Turkmenistan-Iran frontier to the ancient Persian city of Mashhad, a holy city of the utmost importance to Shia Muslims and distinguished by some of the finest Islamic architecture in Iran.

West of Mashhad the Silk Road continued across the semi-desert plains of Khorasan and northern Iran before traversing the foothills of the Elburz Mountains, dominated by the snow-capped cone of 5,671-metre (18,605-ft) Mount Damavand. From here it passed through the old Zoroastrian centre of Rey, a city long since surpassed by nearby Tehran, though the latter was not insignificant when the Silk Road was in its prime. To the south, en route to the Persian Gulf, lay the wealthy cities of Shiraz and Isfahan.

“One is not alarmed by robbers, but…by fierce tigers and lions who will attack passengers, and unless these be travelling in caravans of a hundred men or more…they may be devoured.” Hou Han Shu (5th century Chinese chronicle)

Next came the wild Zagros Mountains, the last serious upland barrier before the Mediterranean Sea. The road passed through Hamadan, a city dating back to 3000 BC that was formerly the capital of the Achaemenids (559–330 BC) and, during the Silk Road’s greatest period of prosperity, the summer capital of the Sassanids (AD 226–651). The surrounding mountains are home to Iran’s Bakhtiari tribe, many of whom are still pastoral nomads.

After leaving the Zagros, the road descended to the plains of Mesopotamia, passing through Ctesiphon and – after its foundation by the Abbasid Caliph al-Mansur in 761 – Baghdad, the modern capital of Iraq and second-largest city in the Arab world after Cairo. The route then led northwest, between the Tigris and Euphrates rivers, to Dura Europos and the eastern frontiers of Syria. Today much of this territory is desert, but in the Silk Road heyday it was forested, and we know from Arab and even Chinese accounts that it supported large numbers of wild animals, including lions.

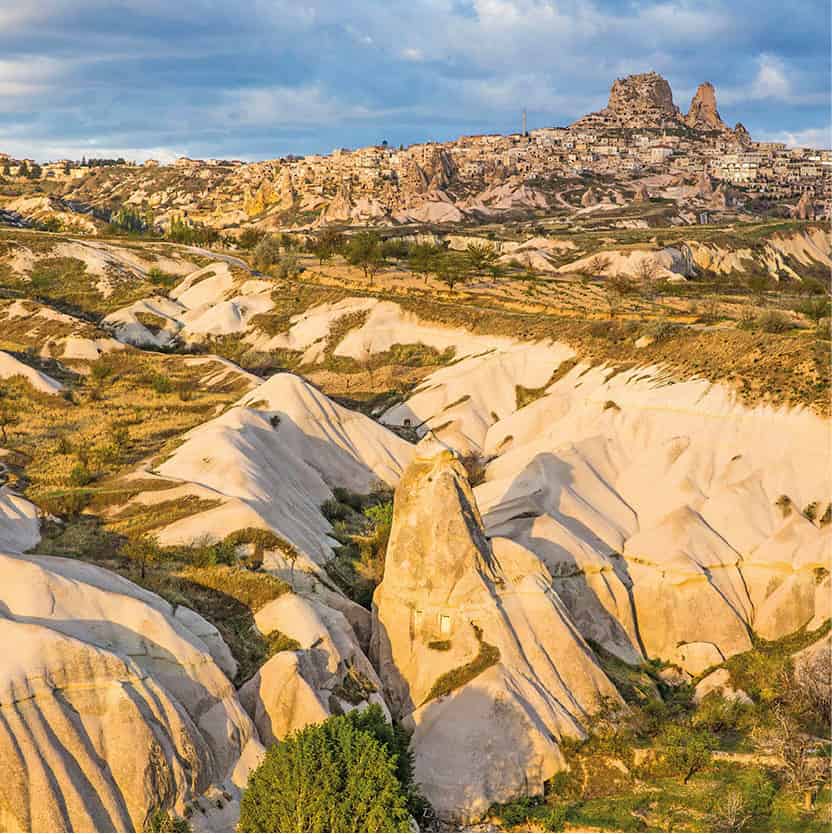

The distinctive landscape of Cappadocia in Turkey.

Getty Images

The next major population centre was the Graeco-Roman caravan city of Palmyra, sometimes called the “Queen of the Desert”. Here the road split, the southern branch leading to the capital, Damascus, while the main, northern branch led through the age-old mart of Aleppo, a trading centre from 5000 BC, remarkable for its Old City, Citadel and souks until the terrible destruction wrought by the conflict of recent years.

As it neared the Mediterranean, the Silk Road branched out, like the delta of a river, from the Levant to Anatolia. One of the main end points was Antioch, today’s Antakya, a somnolent Turkish port – still claimed by Syria – that was the capital of the Seleucid Empire in the 4th century BC. Across the Anatolian plains, the Seljuks secured trade by building a series of hans (caravanserais). Here the Silk Road largely followed the ancient Persian Royal Road before reaching its ultimate destination, the great city of Constantinople.

Architectural gems

The Chinese Silk Road offers awesome natural beauty, but rather less in the way of classical architecture. The ancient cities of the Tarim Basin are largely in ruins, and while Kashgar is justly proud of its great Id Gah Mosque it cannot compare with the architectural gems of Samarkand – the Registan, Bibi Khanum, Gur-i-Mir and Shah-i-Zindah – or Bukhara (with its Poi Kolon complex, Ark citadel and Samanid Mausoleum), or indeed the cities of Iran like Isfahan. In the ruins stakes, Iran also has Persepolis, while further to the west the great city of Palmyra in the Syrian desert was one of the greatest sights of the Silk Road.