Two

THE B&O GROWS

1830–1865

From the B&O’s uncertain beginnings, the railroad would grow to be a regional power and play a key role in the American Civil War. During this time, the railroad opened a branch line to Frederick (1831), to Washington (1835), and reached its stated goal of the Ohio River at Wheeling, Virginia (now located in West Virginia), in December 1852. From its initial 13 miles, the B&O operated 382 miles by the end of the war, with stops throughout Maryland, Virginia, West Virginia, and Washington, DC.

The B&O’s route through Maryland touched major cities and small towns, encouraging growth and providing the impetus of economic development by moving people and goods along its lines. What is commonly referred to today as the “Old Main Line” was initially known as the main stem. Well-known stations opened at Ellicott’s Mills, Sykesville, Mount Airy, Point of Rocks, and Cumberland. Passenger service flourished along its route, serving commuters, immigrants, and long-distance travelers. Freight expanded, and Baltimore benefited the farther west the line reached. It hauled natural resources, such as coal, through the port. Technology advanced as well, as locomotives became more powerful and the early grasshopper locomotives were relegated to yard service.

When the Civil War began, the B&O was the most important rail line in the region. Situated along Maryland and Virginia, its business interests served both North and South. The Washington branch was the only route from the north into the capital, and its line west carried vital natural resources. It was the quickest and most direct route to the Ohio River Valley. Both lines were essential to holding the Union together. The railroad would be constantly disrupted and guarded throughout the war. It was so important that it would eventually be known as “Mr. Lincoln’s railroad.”

In the early days of railroading, the B&O partnered with existing businesses to sell or allow B&O agents to sell passenger tickets. Trains would stop at locations like Sykes Tavern, in present-day Sykesville. James Sykes built a hotel specifically to cater to railroad business, and Sykesville, like many other towns along the line, would grow with the coming of the railroad.

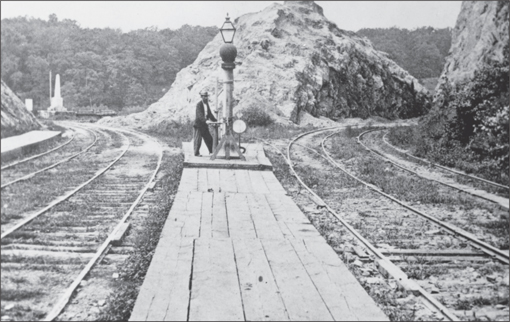

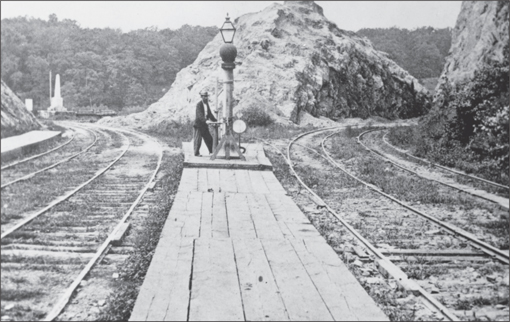

A signalman waits next to a signal stand west of the Relay Hotel at Relay, Maryland. It was here that the B&O’s Washington branch separated from the main line and headed south across the Thomas Viaduct. The tracks to the left turn toward the viaduct and pass the monument to the workers who constructed the bridge. The main stem continues west on the tracks to the right.

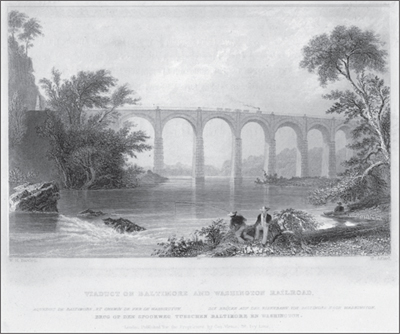

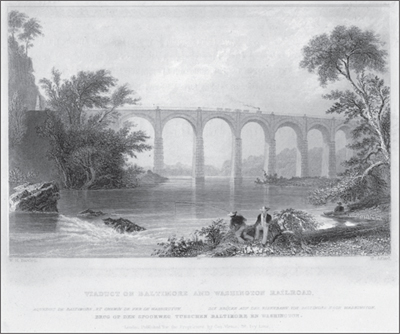

Completed in 1835, the Thomas Viaduct crosses the Patapsco River at Relay and Elk Ridge, Maryland. Designed by Benjamin Latrobe, it is named after B&O president Philip Thomas. The bridge spans over 600 feet and stands about 60 feet above the water. It cost $142,236 to construct and was made from granite quarried in the Patapsco River Valley. A monumental accomplishment, it is still in use today.

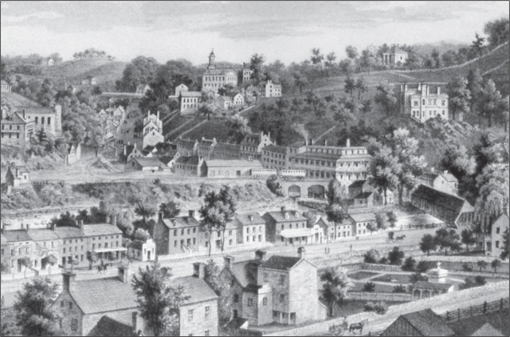

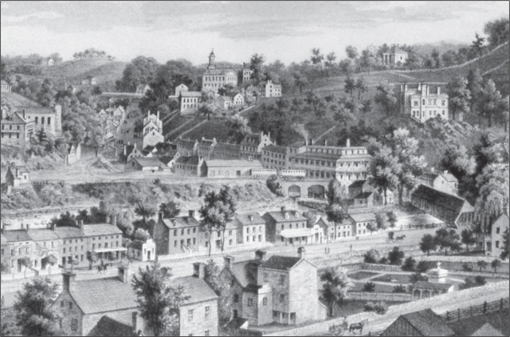

This view of Ellicott’s Mills shows the station in 1854. At this time, the depot (at center, with two passenger cars in front of it) was a freight-only facility. The station would be modified to also serve passengers in 1857. The road in the foreground, the Baltimore & Frederick Turnpike, runs uphill under the B&O’s Oliver Viaduct. (Courtesy of the Maryland Historical Society.)

This 1860s photograph shows Annapolis Junction and the platforms and hotels serving railroad travelers. This is where the B&O connected to the Annapolis & Elk Ridge Railroad and provided rail access to the state capital of Annapolis. The connection proved crucial to the nation during the early days of the Civil War. Union officials used the junction to transport soldiers from Annapolis to Washington, circumventing Baltimore.

The Philadelphia, Wilmington & Baltimore’s No. 51 Phantom sits in front of the Mount Clare depot in the 1850s. The locomotive was a classic “American-type” engine used on many passenger lines at the time of the Civil War. Mount Clare depot appears as it did prior to the construction of the 1884 roundhouse.

Service to Frederick on the Frederick branch began in December 1831. The original depot (pictured above), similar in design to the Ellicott’s Mills station, was built in 1832. It had door access for railcars to enter the building, and it continued to be used as a separate freight depot into the early 1900s. The 1854 passenger station (below) was located on the corner of All Saints and South Market Streets. Pres. Abraham Lincoln’s train stopped here in October 1862 after the bloody battle of Antietam. Lincoln gave an impromptu speech from the back of a passenger car to the waiting crowd, thanking the citizens of Frederick.

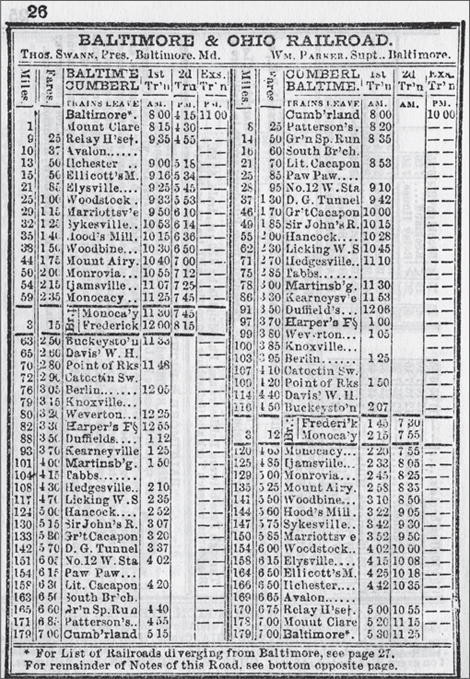

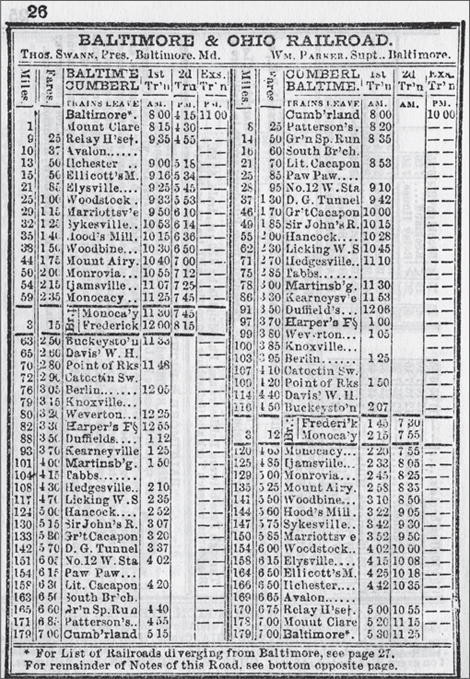

The railroad’s 1840s timetable was included in Appleton’s Railroad and Steamboat Companion. When the guide was printed, the B&O had reached Cumberland, Maryland, a distance given as 179 miles from Baltimore. The entire journey took an incredible 9 hours and 15 minutes, at a cost of $7. The average rate of speed was a little over 19 miles an hour, which included stops for watering, fuel, and food. The guide, and others like it, provided useful information on times and rates. In addition, it included railroads that connected with the B&O and information on the Frederick and Washington branches. It also included information on stagecoach lines, steamboats, and packet steamers. As is the case today, early long-distance travel often required several forms of transportation to complete the journey.

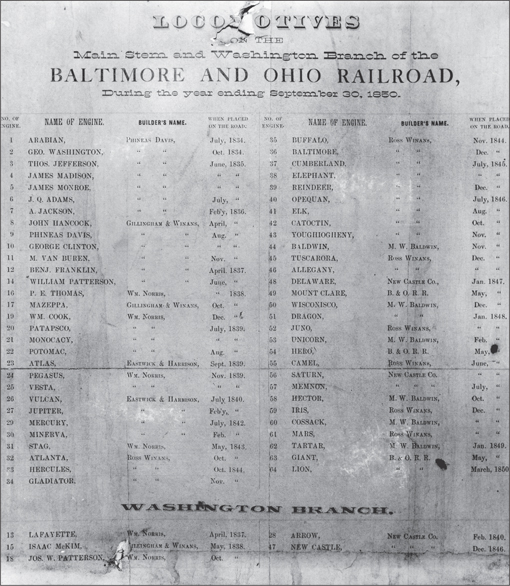

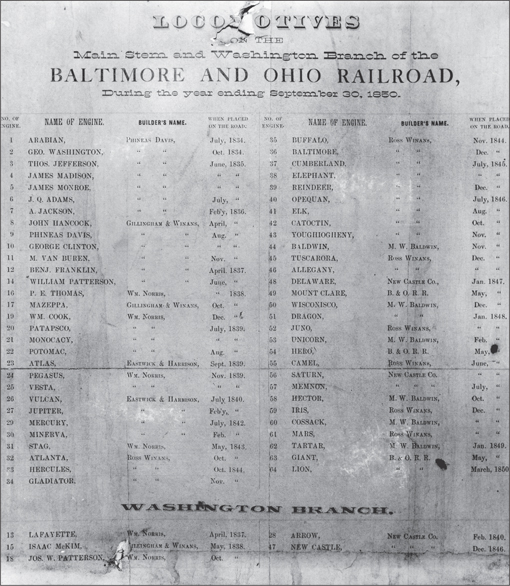

An 1850 roster of locomotives used on the B&O’s main stem and Washington branch lists 64 engines in service. Many of the early grasshopper locomotives built in the 1830s are still in service at this time. Because locomotives could cost as much as $10,000, a large sum of money for the time, it was in the best interest of the railroad to keep any serviceable locomotive in operational condition. Also interesting to note is that the B&O used many contractors to supply its locomotives. The most notable is Ross Winans, who initially worked for the B&O. He built locomotive shops directly next to the Mount Clare Shops to provide more efficient service to the railroad. Winans would become known for creating “Camel”-style locomotives (so named for the placement of the cab directly on top of the boiler instead of near the back). His disagreements over their design led to a major rift with the B&O.

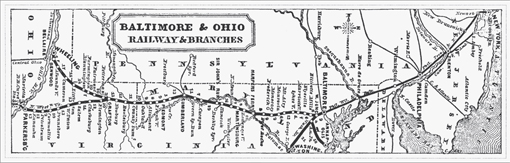

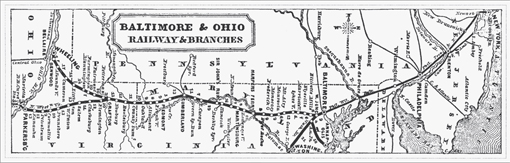

This map shows the route of the B&O in 1860 and its connections to many strategic cities in the region. By the outbreak of the Civil War, the B&O’s line stretched west from Baltimore to Wheeling, Virginia, and over a branch line to Parkersburg, Virginia (both now located in West Virginia). The Washington branch headed south from Relay, Maryland, providing the only route by rail to the nation’s capital from the north during the war. From the B&O’s Annapolis Junction, the Annapolis & Elkridge Railroad provided service to Maryland’s capital. The Philadelphia, Wilmington & Baltimore line provide the northern connection to the B&O between Baltimore, Philadelphia, and, ultimately, New York.

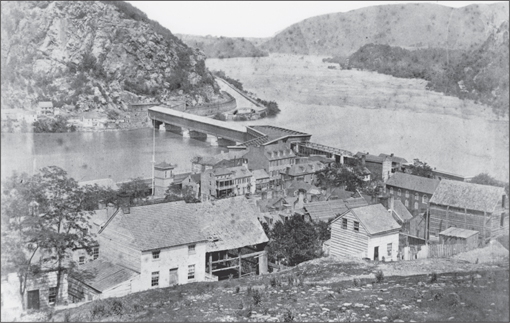

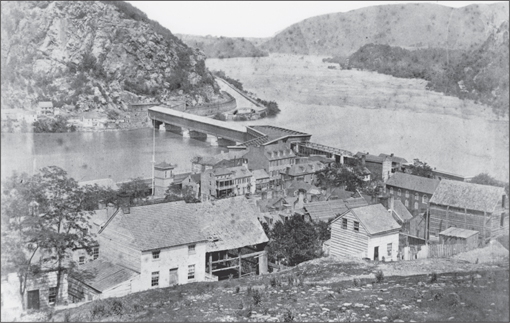

This view from a Harpers Ferry hillside shows the B&O’s bridge and road crossing the Potomac River where it meets the Shenandoah River. On the far side is Maryland Heights. The track heads into Maryland, bearing right along the C&O Canal toward Point of Rocks. The bridge is almost entirely in Maryland, since Maryland owns the Potomac River to the Virginia shoreline.

A B&O passenger train stops outside of Frederick Junction in 1858 during the Artist Train excursion. The branch line to Frederick proved instrumental for the growth of the city. Straddling the Baltimore & Frederick Turnpike and the railroad’s main line, this branch would be vital to the area during the Civil War. The transportation hub was the focus of the Battle of Monocacy in 1864.

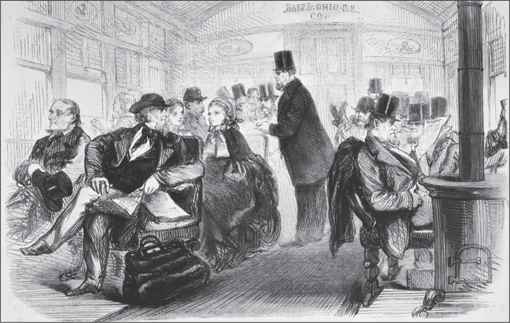

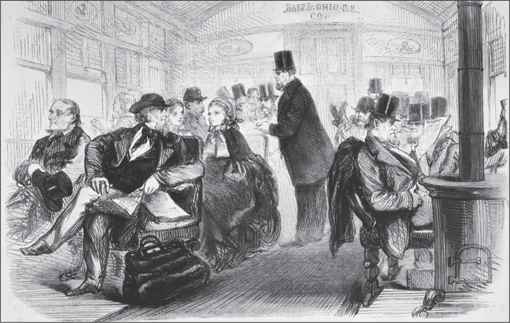

This interior view of a B&O passenger car provides a glimpse of 19th-century rail travel, with all its “comforts.” The cars featured plush seats and were enclosed against the elements. They were heated with stoves, and coaches near the front of the train often had problems with soot when the windows were open. The man standing is a conductor, collecting tickets from passengers.

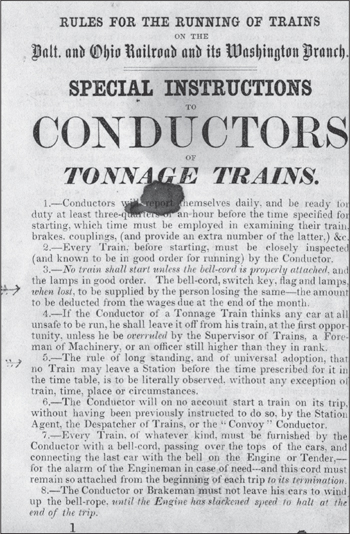

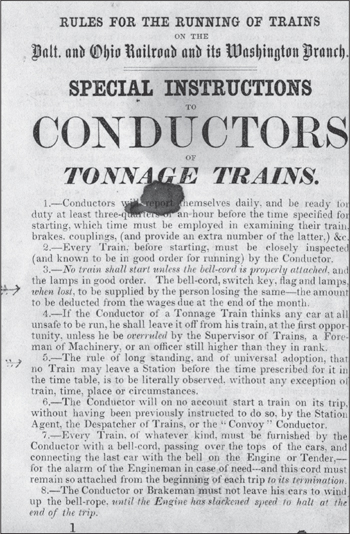

The B&O Railroad provided its employees with rules for operating trains. The page shown here is from an 1856 book that outlined the rules of the road for conductors, engineers, and brakemen. It gave information for the use of whistles and bells for signaling, passing other trains, applying brakes, and managing freight trains. The book was the property of John Shepler, who worked on the Cumberland division.

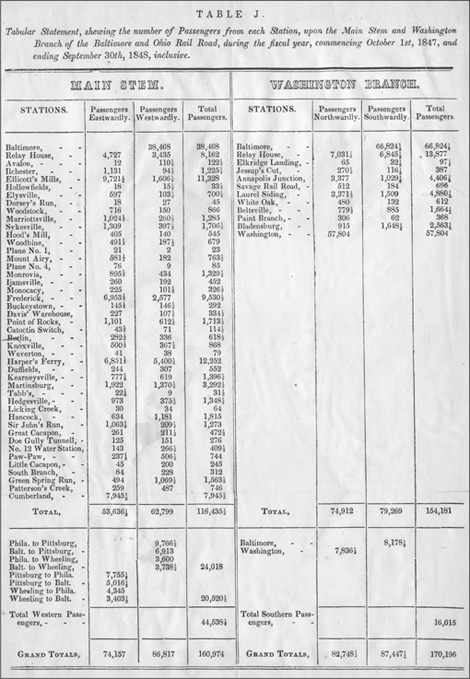

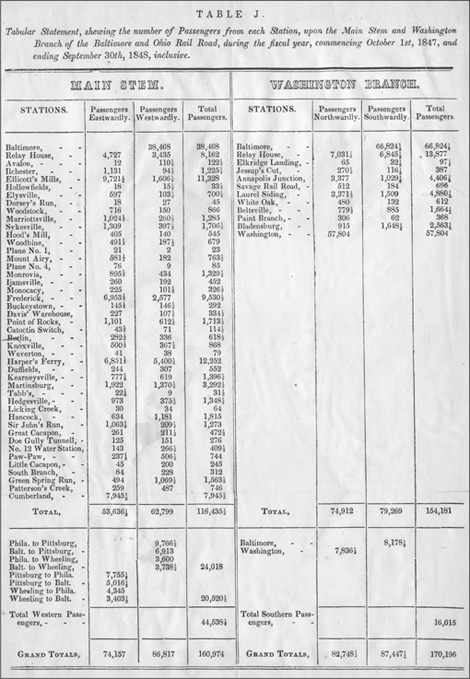

A table from the B&O’s annual report gives passenger traffic totals for the main stem and the Washington branch for the fiscal year running from October 1, 1847, to September 30, 1848. Passenger traffic on the Washington branch was always more significant than that on the main stem and totaled over 154,000 passengers for the year, almost 40,000 more than traveled on the main stem. Baltimore was the leading point of origin for travelers taking both branches. Harpers Ferry and Ellicott’s Mills were second and third, respectively, on the main stem. Washington, DC, was the second-busiest point of departure for the Washington branch. These figures emphasize the growth of passenger travel on the line and the importance of these cities to the region, where industrialization and politics played a major role in their significance.

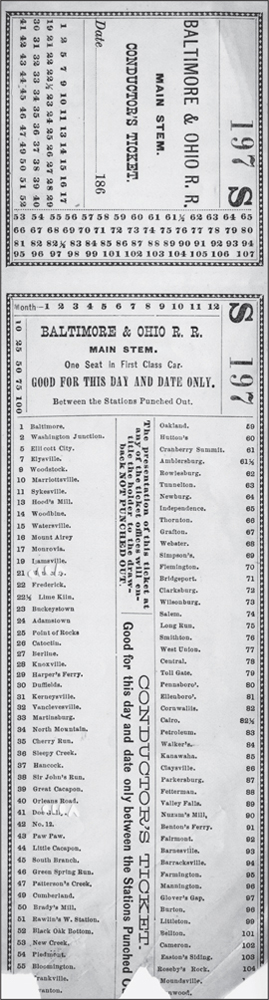

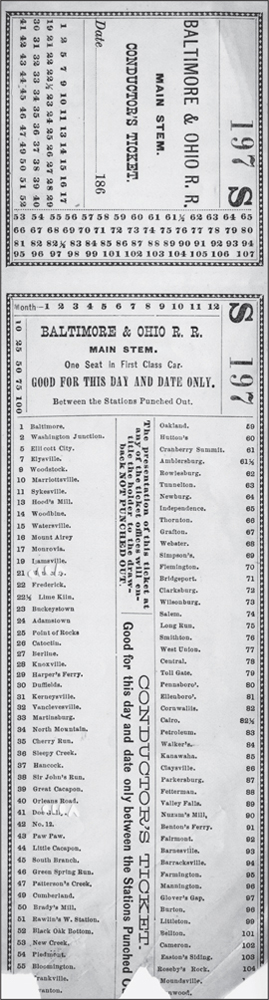

This punched ticket was used for travel on a first-class car in the 1860s. It lists 107 stops along the line between Baltimore, Maryland, and Wheeling, Virginia. The ticket could be torn to allow both the conductor and the passenger to retain a copy. The bottom section listed the stations and their assigned numbers; the shorter portion of the ticket listed just the numbers of the stations.

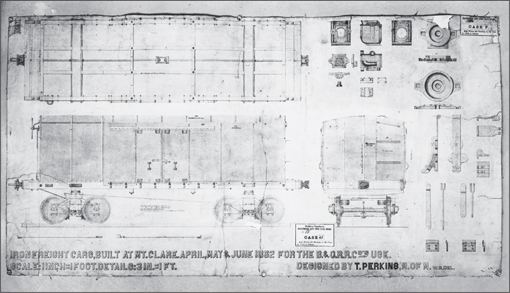

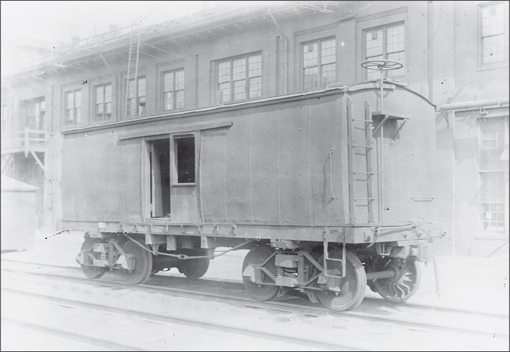

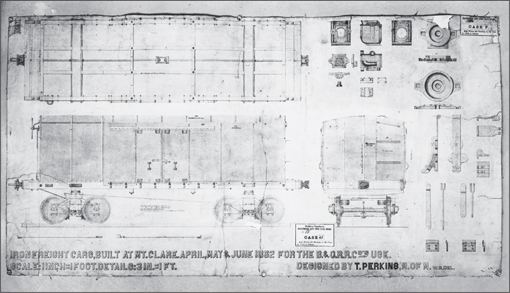

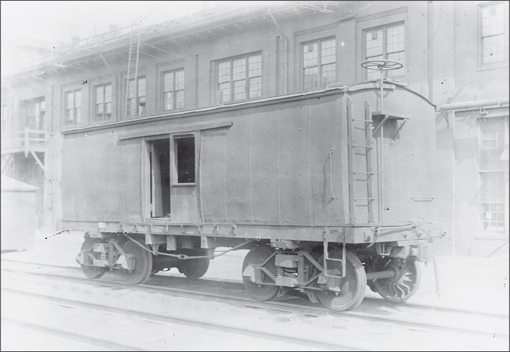

The B&O used iron boxcars to carry freight along its route. These cars were manufactured at the B&O’s Mount Clare Shops using the specifications laid out in the plans above. The cars were designed by Thatcher Perkins, who served as the railroad’s master of machinery during the Civil War. Perkins is sometimes remembered more for the 10-wheel locomotives he designed; however, the iron boxcar proved crucial to rail operations and served as the basis for the Civil War boxcars created to protect soldiers. The photograph below shows a surviving iron boxcar in Baltimore. The collection at the B&O Railroad Museum includes two such cars, one of which was damaged in the roof collapse of 2003.

This 1850s photograph shows a typical coal train on the B&O’s line. When the B&O reached Cumberland and points west, coal became black gold to the railroad and a significant source of revenue. CSX continues to haul coal on the old B&O line to the port of Baltimore, where it is shipped abroad for foreign consumption rather than domestic use.

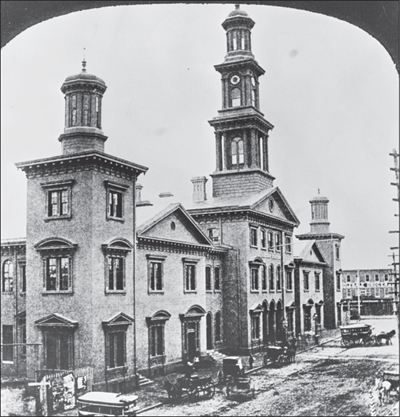

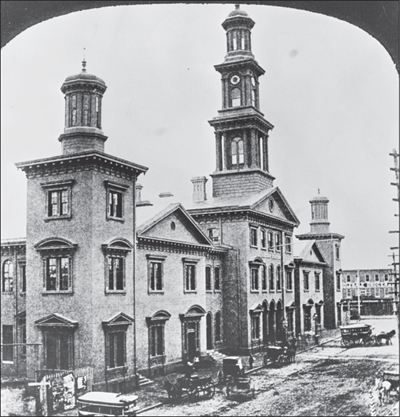

Opened in 1857, Camden Station served as the B&O’s premier Baltimore passenger station and headquarters until the mid-1880s. Designed by Baltimore firm Niernsee & Nielson, it was built in the Italianate architectural style. The railroad purchased the site in 1852 and cleared existing properties and began construction in 1856. It housed offices, passenger accommodations, and freight facilities and saw many changes over its history.

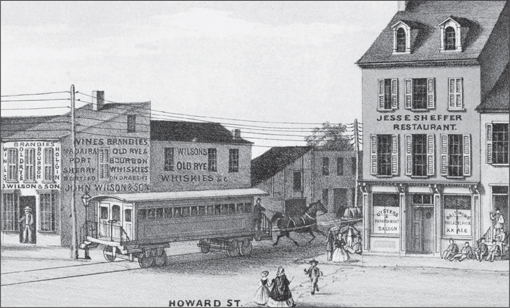

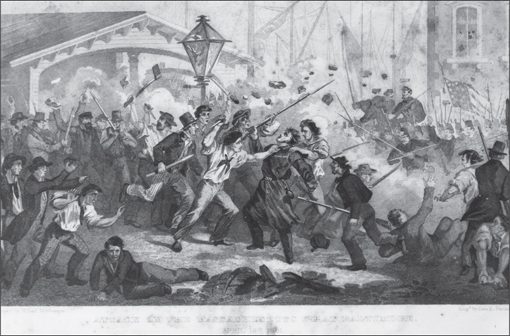

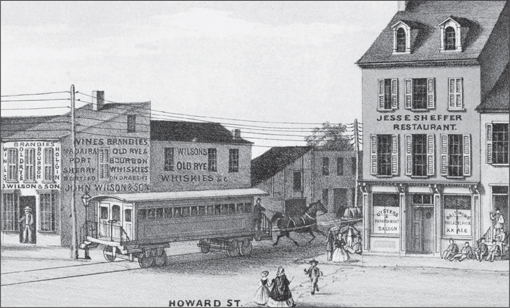

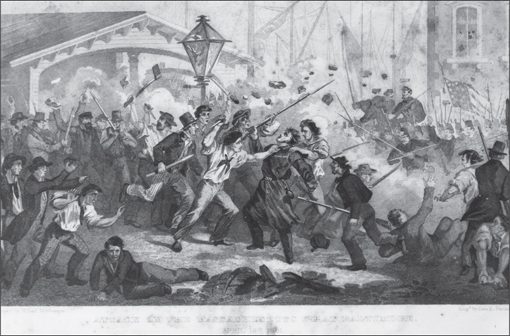

The above image is a detail of a Civil War–era print showing Baltimore City’s Pratt Street and a B&O passenger coach being pulled by a horse. Baltimore City ordinances prohibited the use of steam engines in the downtown business district at the time. The law was created because of the fear of fire, scaring horses, and disrupting business in the bustling downtown. This contributed to the Pratt Street Riot in April 1861. As depicted below, Southern sympathizers attacked a Massachusetts militia moving through the city on its way to Washington following the attack on Fort Sumter. Residents blocked the rails, forcing the troops to march to Camden Station. The ensuing chaos led to casualties on both sides—the first deaths of the American Civil War.

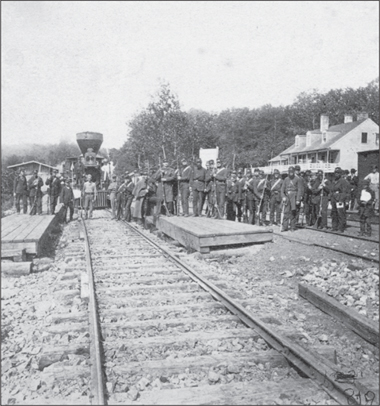

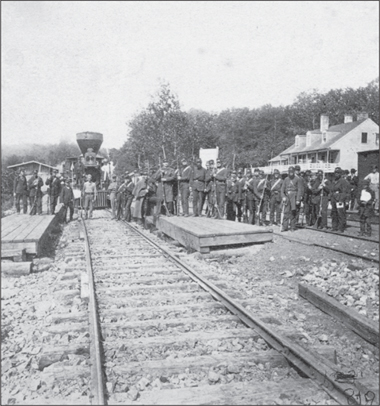

The B&O’s Washington branch provided the only rail route into Washington, DC, from the North, and it was critical that the Union maintain control of the tracks. B&O trains carried hundreds of thousands of soldiers and necessary war supplies throughout the conflict. Vital junctions, like Relay House, were guarded throughout the war against possible sabotage and to ensure the line remained open. Here, Union troops pose on the passenger platforms in front of Relay House.

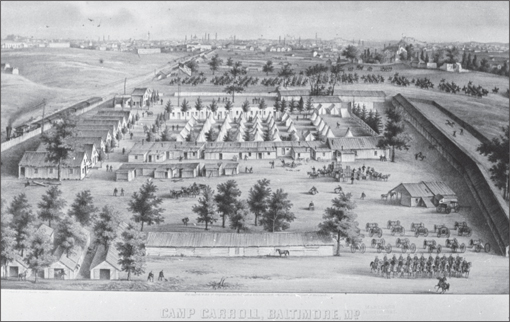

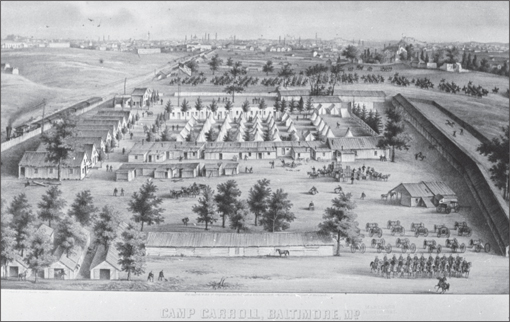

Camp Carroll was located along the B&O’s right-of-way, about a mile from the Mount Clare Shops. The camp served as a training ground for newly formed units. Soldiers from the camp also guarded the railroad and were called out on several occasions to deal with disagreements between pro-Union and pro-Confederate shop workers.

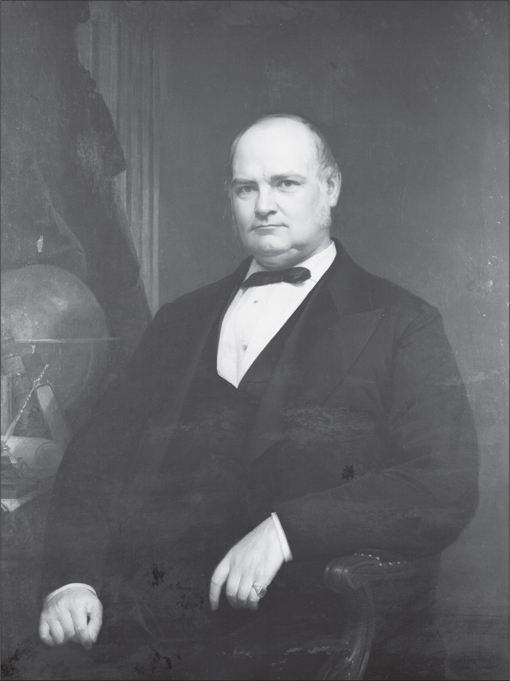

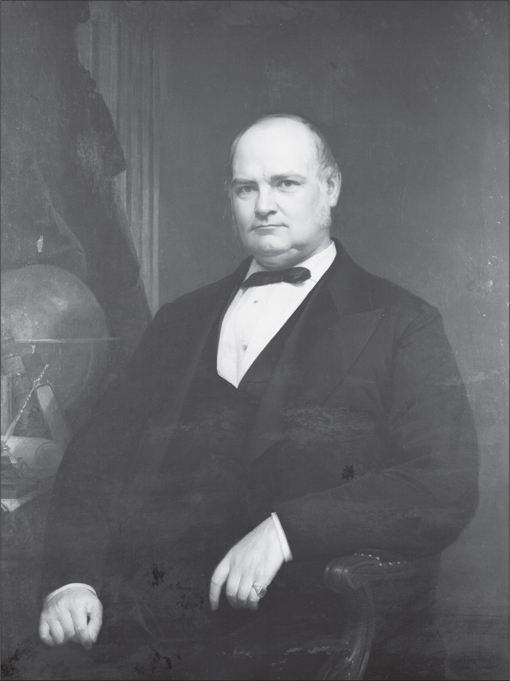

John Work Garrett (1820–1884) was one of the most successful and prominent railroad presidents of his time. He guided the B&O for 26 years, through financial uncertainty, the turmoil of the Civil War, and labor unrest in 1877. Garrett expanded the B&O into one of the most influential railroads in America. Garrett County, Maryland, was named for him in 1872.