Seven

THE MOUNT CLARE SHOPS

1828–1992

The Mount Clare Shops constituted a self-contained industrial city capable of supporting almost every facet of the B&O Railroad. It was the nerve center of one of the most important railroads in America and the site of many railroad firsts as well as the location of the origin of Samuel More’s first telegraph message. Located in west Baltimore, the shops were situated on a portion of an estate owned by James Carroll in 1828. He was a descendant of Charles Carroll the Barrister, a distant relative of Charles Carroll of Carrollton. From humble beginnings, the site would grow to become one of the largest employers in the city.

The shops evolved over time, based on need, and contained one of the first railroad depots in America. Buildings would be added, and eventually, the site would grow to include blacksmith, brass, and foundry shops; passenger car shops; machine shops; bridge-building facilities; locomotive-erecting and boiler shops; air brake shops; a grain elevator; and diesel-erecting shops. Several engine and passenger car roundhouses were added over time, including the sole surviving roundhouse on the site, designed by E. Francis Baldwin in 1884.

The decline of the shops mirrored the fortunes of the B&O. The last steam engine was built on-site in 1948, and fire destroyed the locomotive-erecting shops in 1962. Shortly after this, the B&O merged with the Chesapeake & Ohio Railway, and many functions would be moved to other facilities. By 1976, many of the buildings were unused and in poor condition, and they were demolished as the railroad downsized and eventually sold portions of the property.

Today, several buildings survive and form the core of the B&O Railroad Museum, including the Mount Clare Depot (1851), the passenger car roundhouse (1884), the annex (1884), the passenger car shops (1869–1870), and the freight-car repair shop (1919). Two buildings are in private hands, including the old mill complex (refurbished in 1908) and the test shop (rebuilt in 1924). The legacy of the shops continues, as the museum operates, maintains, and restores locomotives and rolling stock on the property. It is one of the oldest continually utilized rail facilities in the nation.

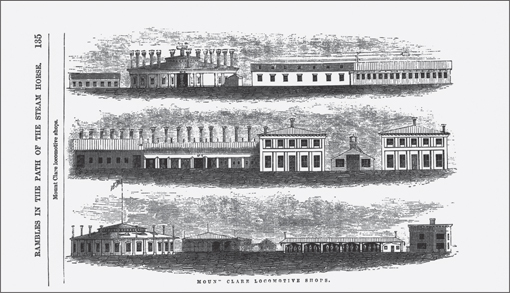

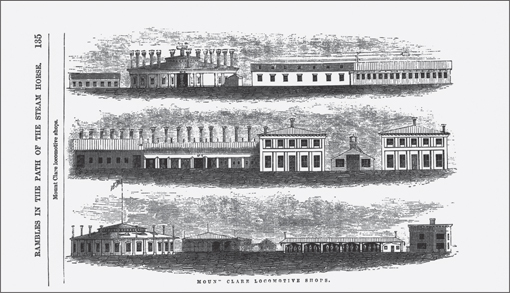

Shown here are the Mount Clare Shops as they appeared on the eve of the Civil War. This illustration comes from Eli Bowen’s Rambles in the Path of the Steam-Horse, published in 1855. The shops had grown to become an industrial city capable of meeting and producing almost all of the railroads needs.

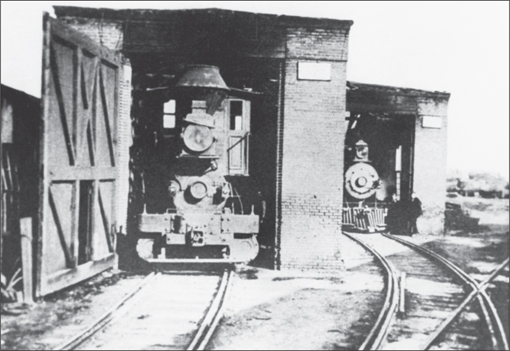

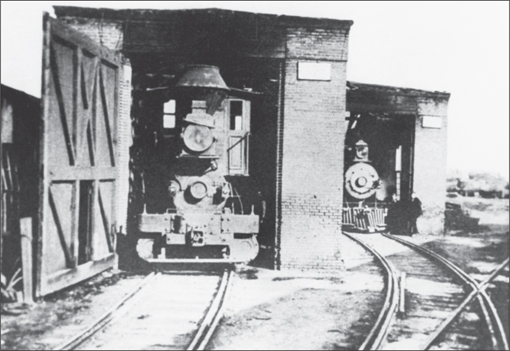

Located on the west end of the B&O Mount Clare property were brick engine houses situated at a 45-degree angle to the railroad’s track. The area was referred to as “Russia,” due to its remote setting. The buildings housed freight and passenger engines ready for service. The engine on the left appears to be one of the B&O’s famous Camel locomotives.

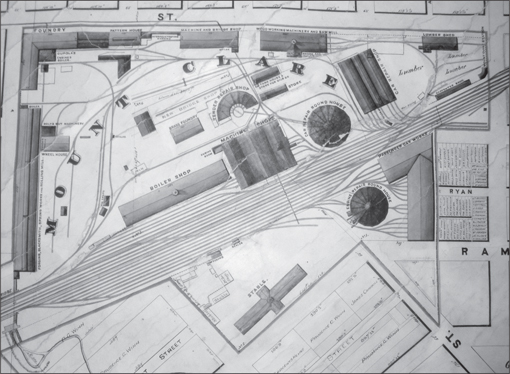

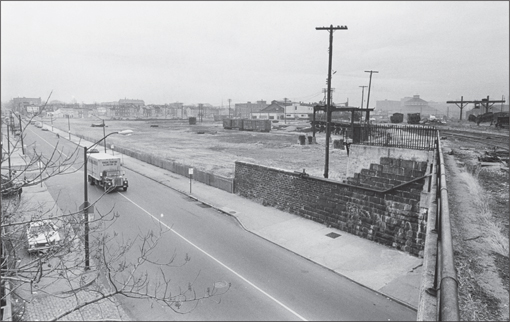

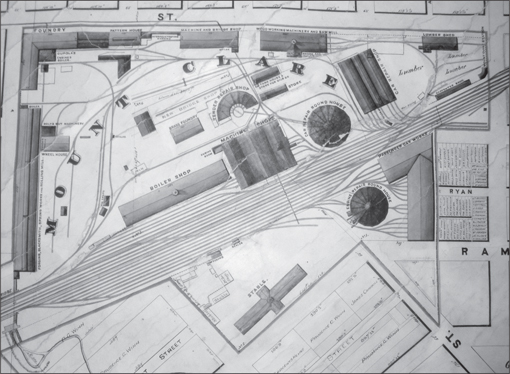

The map (above) shows the Mount Clare Shops in the early 1870s. It is incredible for the level of detail it provides, listing buildings and their functions. Most of the buildings and roundhouses no longer exist. The photograph below looks south across Pratt Street and shows the shops at approximately the same time. The building on the far left is one of the “half arrow” passenger car shops, located on the map’s right-hand side and labeled “Passenger Car Works.” The present-day roundhouse had not yet been built; its current location is the site of the lumber shed and yard in the foreground of the photograph and in the upper-right corner of the map.

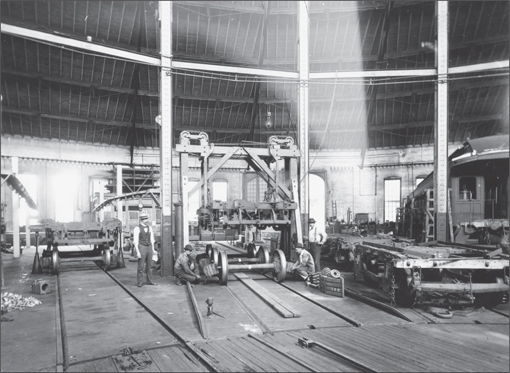

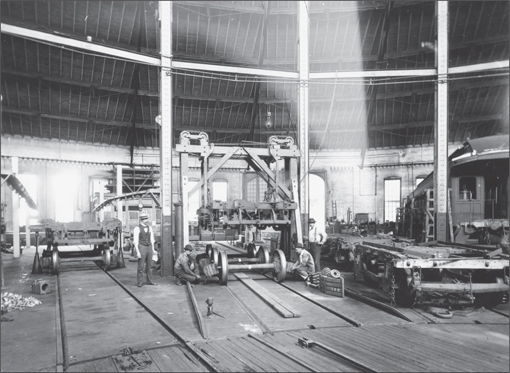

These photographs show the interior of the 1884 passenger car roundhouse, now home to the B&O Railroad Museum. In the above photograph, an employee pulls a passenger coach onto the turntable using a chain-and-pulley mechanism. Built to accommodate the B&O’s passenger coaches, the turntable was 60 feet in diameter. Below, workers use a crane to lower a truck assembly onto a set of passenger car wheels. The railroad could assemble passenger coaches, from the wheels up, inside the 22-bay building. The facility would become outdated by the late 1920s, when the B&O began manufacturing 80-foot-long passenger cars.

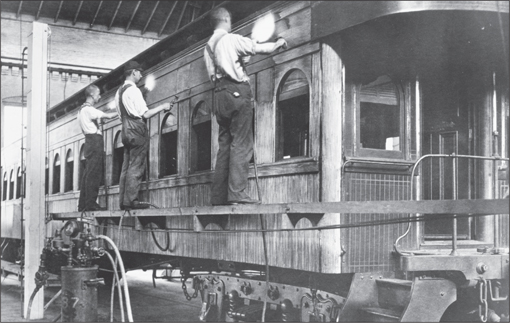

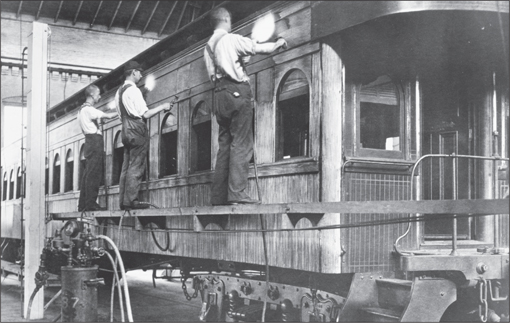

Employees use heat to soften and then scrape paint from the side of a passenger coach in preparation for repainting. The poles with wooden planks stretched between them served as scaffolding to allow work on the sides of the passenger cars at any height. The scaffolding system had adjustable pulleys that allowed the height to be easily set.

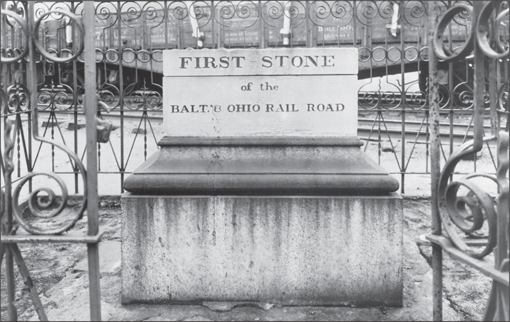

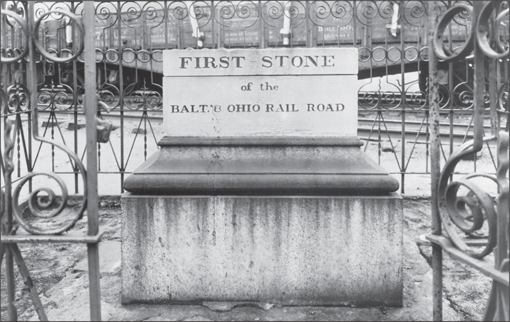

Lost to memory for many years, efforts were made to locate the first stone in the 1890s. It was found buried six feet underground. The stone was removed from the ground and placed on a marble pedestal and surrounded with a steel enclosure. Eventually, it would be removed and placed on display at the B&O Railroad Museum, where it remains to this day.

This c. 1900 photograph shows the interior of one of two smaller roundhouses located at the Mount Clare Shops. Several B&O wooden bobber cabooses are in various states of assembly. The roundhouse’s clerestory level allowed light and ventilation, and a small turntable in the center allowed the cars and wheel assemblies to be pushed into the appropriate bay for work.

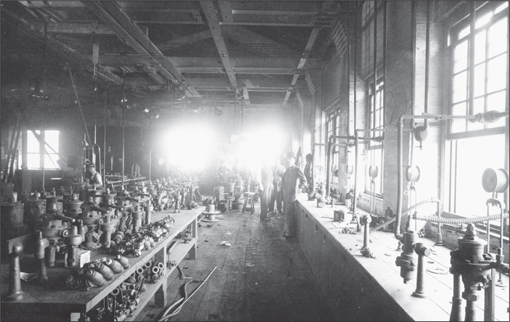

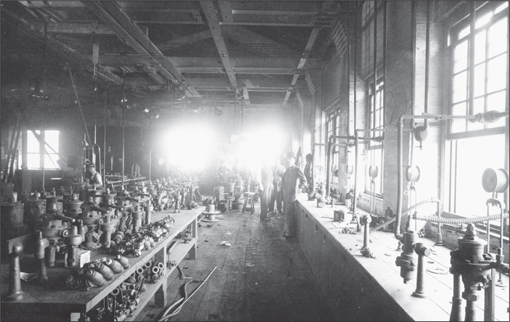

An interior view of the air brake shop in 1915 shows a table loaded with control handles and valves for steam engines. Invented by George Westinghouse in 1868, air brakes revolutionized railroad safety. Air brakes allowed the engineer to control braking from his seat, and valves located in the caboose allowed the conductor to apply the brakes in an emergency.

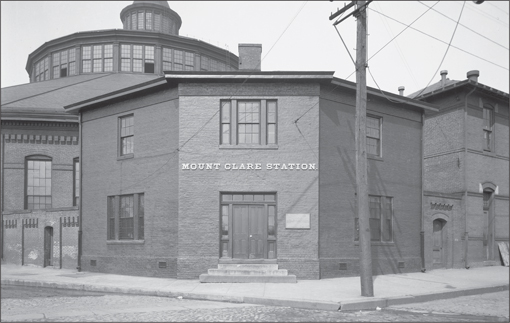

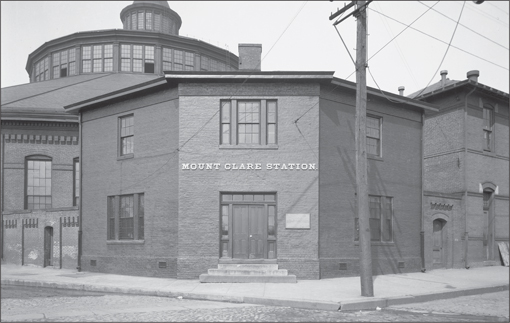

The historic Mount Clare Station and B&O’s passenger car roundhouse are seen here in the 1920s. Located on the corner of Poppleton Street, the station dates to 1851. It replaced a wooden structure on the site that had been used for passenger and freight service. The plaque on the building erroneously claims the station was built in 1830; however, subsequent research clearly proved this was not the case.

Located behind the roundhouse was an air-conditioning test shed. The building was 90 feet long and 28 feet wide, long enough to allow a passenger car to be brought inside for testing. The B&O was the first railroad to experiment and install air-conditioning on its coaches, in 1931. The shed was constructed in the early 1930s and was still in place in the 1950s.

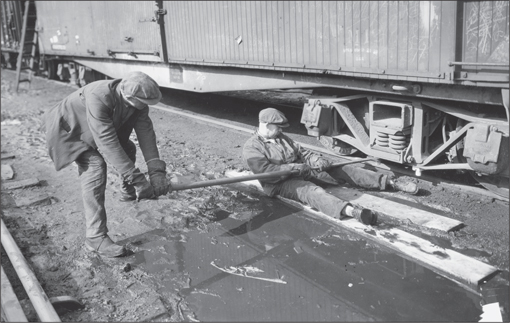

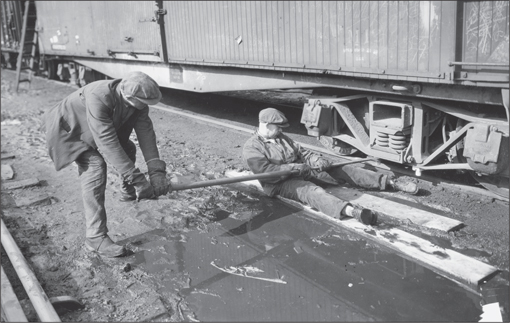

Workers at the Mount Clare Shops tighten the bolts holding an arch-bar truck together on a B&O boxcar sometime in the 1930s. Not all railroad jobs were as glamorous as the engineers or conductors, as this photograph shows. The use of wooden boards to stay dry shows a good bit of ingenuity on the part of the workers, performing an otherwise thankless but necessary job.

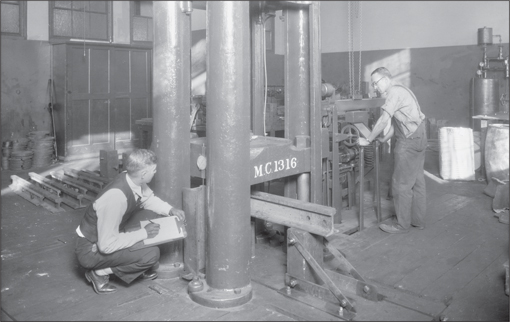

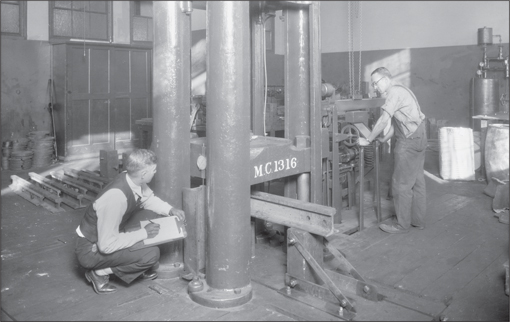

B&O employees test the strength of a rail at the Mount Clare Shops. Quality control and constant review were important for safety as locomotives and rolling stock grew in size and weight. Rail defects and failure, caused by a variety of reasons, including manufacturing problems, inadequate design, or wear, could have deadly results.

Mount Clare workers use compressed air to tighten bolts on the joint bar connecting two sticks of rail. The unique frame mounted on railroad wheels contains an I-beam that supports and holds the heavy weight of the rotary machine used to tighten the bolts. The Mount Clare passenger car repair roundhouse is in the distance.

Female workers from the Mount Clare Shops pose with their tools. During both world wars, the B&O hired women to work in what were typically male occupations. They worked in the shops, as machinists, on rivet crews, and on track gangs, in addition to more traditional roles as station maids, car cleaners, telephone operators, and office clerical workers.

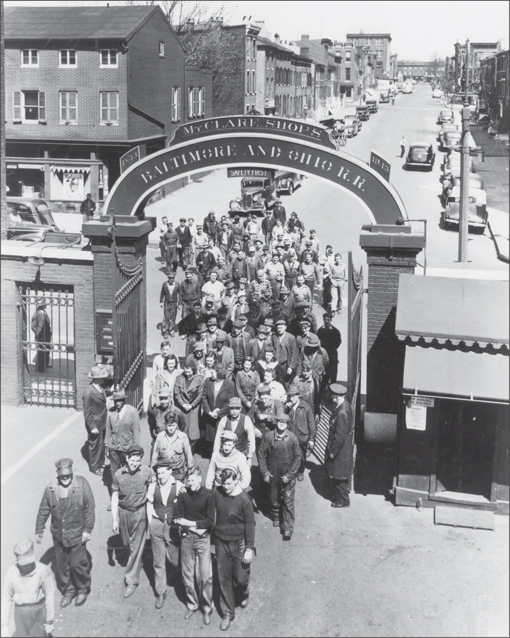

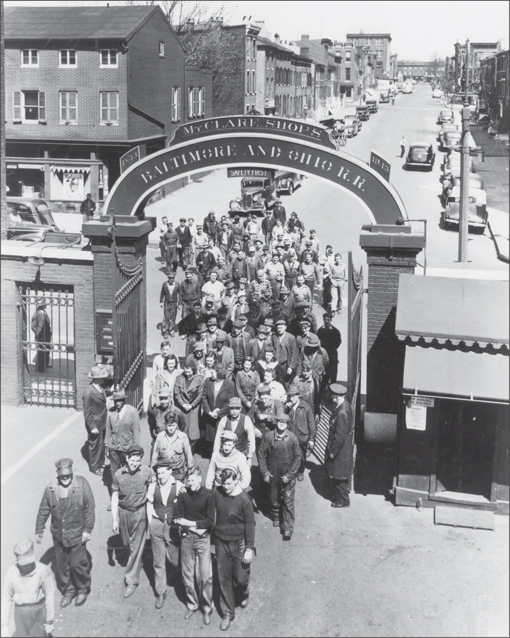

Workers file past B&O police at the railroad’s main gate on Arlington Avenue. This 1943 photograph is likely a public relations product. During the height of World War II, the B&O benefited from the increased demand for military hardware and other supplies, which spurred an upturn in the American economy and an increase in rail traffic. In order to help the B&O and other railroads cope with an increase in demand and a shortage of labor, many workers pushed back or returned from retirement, and women were hired in increasing numbers to fill the gaps. The gate served as the main entrance to the site for countless generations. Images of the entrance can usually be dated because the railroad changed the year on the sign above the gates. The metal gates still exist and are in storage at the B&O Railroad Museum.

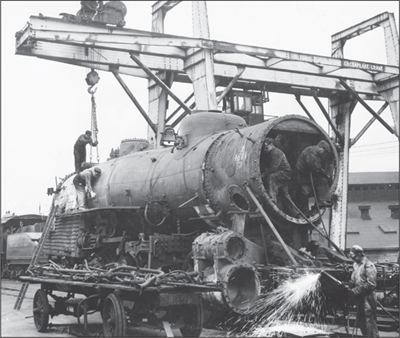

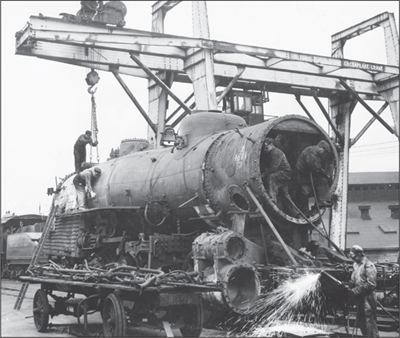

Mount Clare workers strip down a Mikado locomotive prior to a major rebuild. Baldwin Locomotive Works built the first Mikado 2-8-2 locomotives for shipment to Japan around 1900. Many of the B&O’s Mikado locomotives dated to the 1910s and were rebuilt in the 1940s. This extended the service life of equipment that was 40 or 50 years old. The engines continued in service until the mid-1950s.

Constructed in 1910, the grain elevator at the Mount Clare Shops is shown here in the 1940s. This towering building dominated West Baltimore’s skyline for years and served as a loading point for bulk transportation in B&O freight cars. It also served as a photography platform, providing a bird’s-eye view of the shops. It was dismantled in 1976.

This celebration marks the completion of the 40th, and last, T-3 locomotive to enter service on the Baltimore Terminal Division. Almost 2,000 workers joined B&O president Roy B. White and company officials for the send-off. The rally took place on October 18, 1948. The No. 5594 was dropped from the company roster in 1956, only eight short years after entering service.

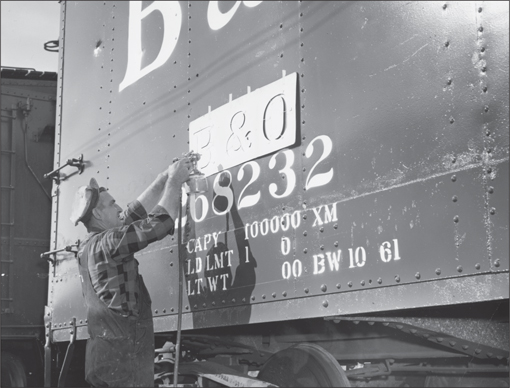

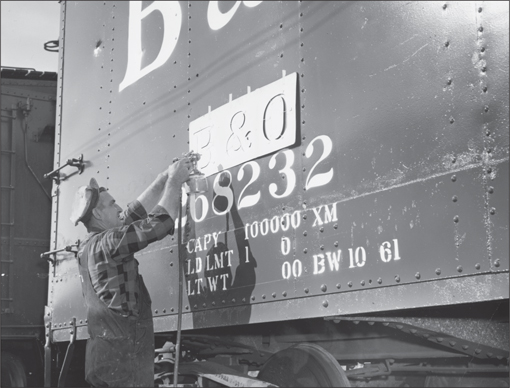

A painter stencils “B&O” on the side of a freight car using an air-gun sprayer. Stenciling and painting a railcar was a skill. Stencils were handmade from cardstock and metal wire and were taped or held in place while the paint was applied. Even with the advent of air-powered sprayers, car lettering was still done by hand well into the 1940s and 1950s on some B&O passenger cars.

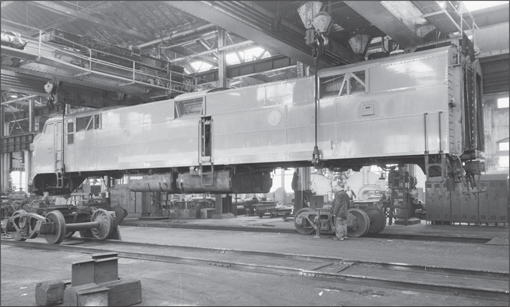

Shop workers performed a variety of tasks on freight and passenger cars at the Mount Clare Shops. Here, two employees lower a truck assembly onto a set of wheels in the late 1950s. They are aligning the assembly by using the journal box covers to push and guide it into place.

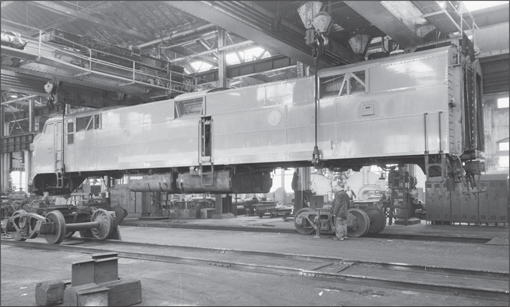

Located on the eastern end of the locomotive-erecting shop was the smaller diesel-erecting shop. The 300-foot-long shop provided maintenance facilities for a growing fleet of diesel engines. It contained cranes capable of lifting locomotive bodies or replacing diesel engines. Diesel technology first appeared on the B&O in 1925 and would eventually spell the end to the steam era, as diesel locomotives proved more cost-effective to operate and maintain.

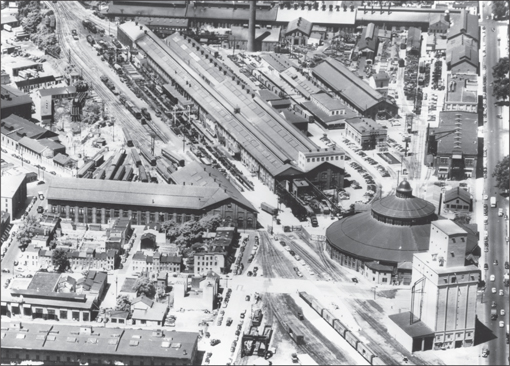

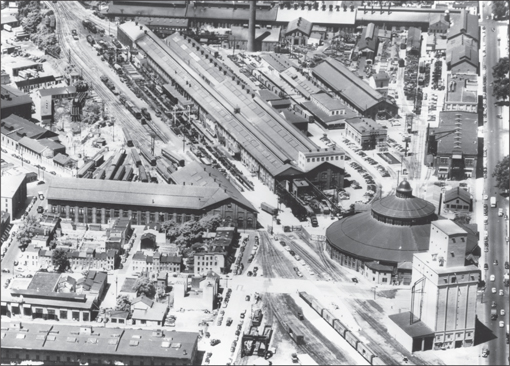

This aerial photograph of the Mount Clare Shops looks west in 1953. The site is seen prior to its decline in the 1960s and 1970s. At lower right is the grain elevator and the 1884 roundhouse that housed the newly opened B&O Transportation Museum. At center, positioned diagonally, are the machine and locomotive-erecting shops. The L-shaped buildings to the left are the passenger car shops.

Pictured here are the bustling tracks of the Mount Clare yards, looking east toward Baltimore in the late 1950s or early 1960s. The diesel engine on the left is a Fairbanks Morse H12-44 switcher, built in 1957. No less than 10 tracks at this point in the yards are occupied by both freight and passenger cars. The roundhouse and car shops can be seen in the distance.

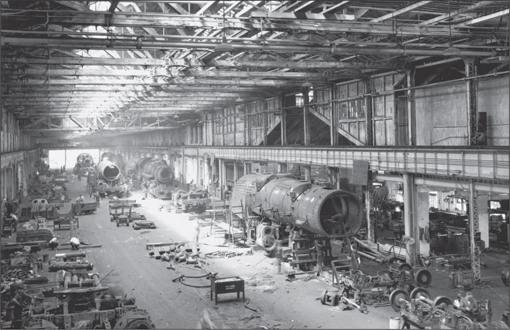

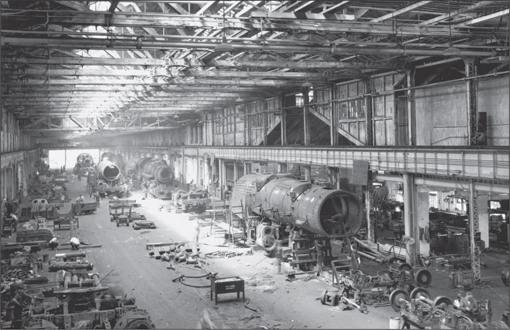

The above photograph provides an incredible view of the interior of the locomotive-erecting shop, also known as the boiler shop, during the heyday of steam in the 1920s. At least five steam engines are being serviced in this huge structure, which stretched over 1,000 feet. Located behind the present-day roundhouse, the building expanded to cover a significant part of the shop property. Large windows allowed additional light into the building, and an overhead crane was one of two 80-ton cranes that provided massive lifting power. The erecting shops burned down in 1962, gutting the figurative heart and soul of the B&O’s operations. The C&O Railway purchased the B&O in 1963, and while the shops continued to function, the erecting shops were not rebuilt.

The B&O cleared the abandoned and unused buildings in 1976. Here, the wreck cranes demolish a portion of the foundry on the corner of Pratt and Carey Streets. The only historic structures to survive demolition were the roundhouse (1884), annex (1884), Mount Clare Station (1851), the north and south passenger car shops (1867), the sawmill (rebuilt in 1908), and the office building and test shop (rebuilt 1924).

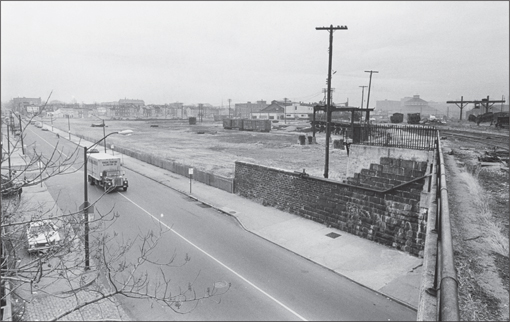

This photograph looks northeast across the Carey Street Bridge after the majority of the old shop buildings had been cleared in 1976. Gone are the brass foundry, iron foundry, and the blacksmith shop that lined the street, all dating to the 1860s. The site is currently home to a shopping center called Mount Clare Junction.