INTRODUCTION

The Strange Career of Len Zinberg

In 1967, the multimillion-copy selling, tough-guy mystery writer Ed Lacy published yet another of his highly successful mass-market detective stories featuring an African American protagonist, In Black and Whitey. The new novel was unlike Lacy’s previous, award-winning series of mysteries about a Black private eye named Toussaint Marcus Moore. Moore confronted the subtleties of racism while solving crimes in unusual settings, such as small-town Ohio and Mexico City. Lacy’s In Black and Whitey featured an African American police officer, Lee Hayes. Hayes is assigned, with a white partner, to cool off an explosively hot political situation in the Harlem ghetto.

In Black and Whitey is told entirely through the eyes of the young, very raceconscious Hayes, who sympathizes with many of the aims of the new Black Power movement even as he is skeptical of the motives and strategies of some of the self-proclaimed Harlem leaders. Moreover, Hayes is alternately intrigued and mystified by the personality of his white partner, Albert Kahn, who has a sort of dual ethnic identity. At times, Kahn is identified as “Whitey” by Hayes and also by some of the Harlem Black Power militants; he is undifferentiated from the Euro-American majority with its caste privilege. In other moments, the African American Hayes is acutely conscious of Kahn as a Jew, in ways that differentiate Kahn from other “whites.” Hayes takes note of Kahn’s supposed Jewish physical features (such as a “thick nose”) as well as his putatively Jewish “braininess” and bookishness.1 Kahn is also an obsessive weight lifter and consumer of natural foods. Moreover, some of the more fervent nationalists in the Black community, where Hayes and Kahn go under cover disguised as social workers carrying out an “Ethnic Survey,” immediately direct anti-Semitic remarks at Kahn, calling him “Jewboy” and denouncing “Jew control.”2

Kahn appears to have a classic left-wing attitude toward Jewish identity, abhorring anti-Semitism but making no concessions to Jewish particularism. Kahn is quick to mention that his parents “died in a Nazi oven.”3 However, he is equally quick to denounce Jewish nationalism and chauvinism. He admits that Jews can hold ignorant racist sentiments, even as he corrects one Black militant who thinks that the Yiddish word schwartzer (sometimes spelled schwartze) is necessarily tantamount to the epithet “nigger.”4 Expressing with a disconcerting articulateness his views about culture and history, Kahn goes so far as to repudiate all notions of ethnic heritage as the determinant of one’s worth, Jewish, Black, or otherwise. Paraphrasing Henry Ford’s famous comment on history, Kahn declares that “heritage is bunk” and argues in favor of “environment” as the explanation of differences in group behavior.5

Gradually the African American Hayes is attracted to Kahn, and indeed, so may be the reader who brings to the book a curiosity about or sympathy for radical politics. After all, despite Kahn’s occasional odd proclamations, one begins to sense that he may be a secret Red. Early in the novel Kahn corrects one of his police superiors who is worried about “riots in the Negro community”: “‘Well, sir . . .’ [Kahn] said, in that considered way he talked, ‘I look upon them as rebellions, not riots. I think many Negroes have reached the breaking point in ghetto fatigue; they’ve had it. Marches no longer mean much, and at best they provided only a minor frustration release. . . . If I was in a Negro ghetto, I think I’d be leading a pretty fair revolt myself.’”6 When one of the Harlem Black Nationalists offers a popular version of Frantz Fanon’s theories urging “colonials to fight and destroy Western civilization, as a form of revolutionary therapy,” Kahn steps in with a factual correction: “‘Fanon was born in Martinique, where Negroes are the majority. And with the Algerian rebels, the FLN, Fanon was working in a country where he was again on the side of the majority. Hence his theories only apply to an area where the . . . colonials constitute the majority of the population and not to a country where the colonials are but a small minority. I’ve read his Wretched of the Earth, and he does not advocate his theory for the U.S.’”7 At one point in the novel, another white cop, an overt racist, sneaks up on Kahn and knocks him out for being a “‘nigger lover.’”8

The suggestion that Kahn, the Jewish cop, is a Leftist, as is Hayes, the Black cop, is reinforced if the reader recognizes that the names of the two officers who are trying to “do the right thing” in Harlem are the same as those of two famous pro-Communists: Lee Hayes (1914–81) was a singer and songwriter for Pete Seeger’s Almanac Singers and the Weavers as well as a minor mystery writer who appeared in the same publications as Lacy; Hayes was white but known for his use of Black musical traditions.9 Albert Kahn (discussed in Chapter 4) was the author of popular radical books on foreign policy, a contributing editor of the New Masses, a founder of the World Peace Council (generally regarded as a “Communist Front”), and co-owner in the 1950s of the left-wing publishing house Cameron and Kahn Associates. The use of Leftists’ names in Lacy’s novels is not merely coincidental. One of the villains in In Black and Whitey is named Eugene Lyon; Eugene Lyons (1898–1985) was a famous apostate from Communism who wrote the classic 1941 anti-Communist work The Red Decade: The Stalinist Penetration of America. Lacy’s earlier Black private eye, Toussaint Marcus Moore, was named after three political activists: Toussaint L’Ouverture, the leader of the Haitian Revolution; Marcus Garvey, the founder of the largest Black Nationalist movement in U.S. history; and Richard B. Moore, the famed Caribbean-born Communist who ran the Frederick Douglass Bookstore in Harlem. However, in the astounding and unexpected denouement of In Black and Whitey, it turns out that Kahn is not left wing but the villain of the novel. He has taken the Harlem undercover assignment precisely to ignite a race riot that will create a white backlash, and in the end, Albert Kahn engages in a bloody hand-to-hand battle to the death with Lee Hayes.

Can Ed Lacy’s portrait of a Jewish betrayer who takes advantage of the kindness, trust, and generosity of his Black partner actually be a vile contribution to anti-Semitic ideology? If so, of what race, ethnicity, and political orientation might the author of In Black and Whitey actually be?

To the contrary, the novel is hardly anti-Semitic, because it turns out that Officer Kahn is not really Jewish but the “100% Aryan” son of Nazi Party members who fell out of favor with Hitler over tactical differences and were sent to a death camp.10 Kahn is identified as not being Jewish near the end of the novel by Mr. Herman, an “authentic” Jew—a shopkeeper who lives in Harlem and whose daughter Ann is active in the civil rights struggle. Herman notes, “In Europe a name like Kahn can be Jewish or gentile. One of Hitler’s worst beasts was a Rosenberg.”11 Moreover, the author of In Black and Whitey, Ed Lacy, although thought by some readers to be an African American and, indeed, credited as the creator of the first Black detective and included in at least one collection of Black authors, was himself Jewish, born Leonard S. Zinberg.12

Despite the plot twist, the politics of the book are abundantly of the Left. Social reform, especially liberalism, is depicted as an insufficient solution to racist capitalism. Hayes rejects the ultraleft nihilism of the extreme nationalists as well, but he has something of a Leninist view of “the National Question”; that is, Hayes does not equate the extremist nationalism of the oppressors (e.g., white supremacism) and the Black nationalism of the oppressed. Such an equation is the way that the other, more careerist Black officers choose to see things. Moreover, although the novel includes no didactic lectures on “the Jewish Question,” its symbolic action seems to suggest that Jews can only oppose racism and fascist movements by becoming “race traitors” to whiteness. The action of In Black and Whitey argues that race hatred, in the form of white supremacism, is an American form of fascism, and the color line (“the visibility factor”) is fundamental. That is, race hatred takes root when any minority that can “pass” for white, such as Jews, allows itself to be absorbed even temporarily into the culture based on white identity and therefore privilege; the result will be that “the only minority in the U.S. will be colored.”13 Unlike the Jews of Europe, Jewish Americans have a choice about color, but to identify primarily as “white” could lead Jews to tacitly aid fascism. Most telling for Lacy’s political education in the Old Left is his plot of American Nazis fomenting anti-Semitic ideology to ignite a race riot in Harlem in the late 1960s; this conspiracy theme is lifted directly from the controversial analysis by the Communist Party of the Harlem Riot of 1943, an episode that will be discussed at length in Chapter 4.

At the novel’s end, the police, both white and Black, cover up the truth about Kahn. They place the blame for the Harlem troubles on the Black Power movement instead of on the white supremacists and facilitate Kahn being trumpeted in the newspapers as a heroic son of concentration camp victims who gave his life to stop racial violence. When Hayes reads in the papers a proclamation by the mayor of New York that the situation in Harlem was defused by “Negro-Jewish-Italian-Irish teamwork on the part of New York’s finest, truly an all-American team,” he renounces the police force for its “fink stink” and decides to accept his girlfriend’s offer to move to the Caribbean.14 The political implications of the overall narrative design express a Marxist sensibility: The state power constructs a false history in an almost “naturalized” way, the police infiltrate the Black ghetto in the guise of social workers conducting an ethnic survey, and the liberal rhetoric of “multiculturalism” is glibly invoked by the city administration to celebrate a spurious victory that changes nothing.

To what extent can In Black and Whitey be written off as an anomalous product of the late 1960s, a bizarre work by an unregenerate Leftist who happened to be on the scene and sought to capture the zeitgeist? Ed Lacy was, in fact, a mass-market phenomenon throughout the entire Cold War era; at his death in 1968, the year after In Black and Whitey came out, the New York Times reported that 28 million copies of his novels had been sold in twelve countries.15 Moreover, Ed Lacy was far from atypical. His biography, political evolution, absorption with the ideology of racism, and dual literary career (before the Cold War as Zinberg, then under the name Lacy and other pseudonyms) are very much rooted in the generation that came of intellectual age during the antifascist crusade. Trinity of Passion will demonstrate that what, at first, might seem to be the strange career of Leonard S. Zinberg ends up being perhaps not so strange after all.

The career of Leonard Zinberg is offered here at the outset not merely to unveil the hidden identity of Ed Lacy—as a secular Jew, a former Communist, and a proletarian writer turned pulp writer extraordinaire. The career of Zinberg is also

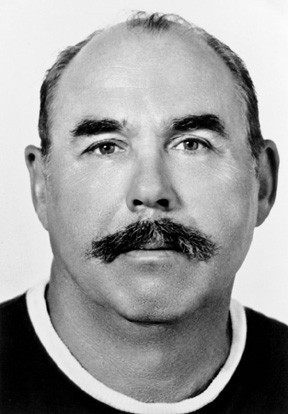

LEONARD S. ZINBERG was a pro-Communist novelist in the 1930s and 1940s who reinvented himself during the Cold War as a leading pulp fiction and mystery writer often featuring African American characters. Under the name Ed Lacy he sold millions of copies of his books and won a prestigious award. (From the Zinberg Collection in the Howard Gotlieb Archival Research Center at Boston University)

exemplary for its birthright in the antifascist crusade, its transit from the small magazines of the Left to the mainstream publications of mass culture, its manifold engagements with the ideology of racism and the travails of working-class life, and its dogged loyalty to fundamental class-based ideas of social transformation, albeit in a changing world.

Leonard S. Zinberg, known as Len, was born in 1911 in upstate New York to Max and Elizabeth Zinberg. The couple was divorced a few years later, and Elizabeth married Maxwell Wyckoff, a Manhattan banking lawyer. After age ten, Len resided with his mother and stepfather on West 153rd Street, at the edge of Harlem.16 For a while, in the late 1920s, he attended City College of New York, and in the early 1930s he traveled across the country, working at odd jobs. Then his stories started to appear under his own name in pro-Communist publications such as the New Masses, Blast, and New Anvil and in commercial publications such as Esquire, Coronet, and Story. In 1940 he published Walk Hard, Talk Loud, about an African American boxer in love with a Black Communist activist. This was produced as a play in 1944 by the American Negro Theater Company in Harlem, with a script by an African American veteran of the Federal Theater Project, Abram Hill (1910–86). The responses to Zinberg’s first novel by African American writers from a range on the political spectrum were sympathetic to his cross-cultural efforts. Ralph Ellison’s comments in the New Masses merit quoting at length, inasmuch as they might seem surprising in light of Ellison’s later reputation:

For several years Len Zinberg, a young white writer, has been producing short stories that reveal an acute and sympathetic interest in the Negro’s problems. . . .

[In] Walk Hard, Talk Loud [he] indicates how far a writer, whose approach to Negro life is uncolored by condescension, stereotyped ideas, and other faults growing out of race prejudice, is able to go with a Marxist understanding of the economic basis of Negro personality. That, plus a Marxist sense of humanity, carries the writer a long way in a task considered extremely difficult: for a white writer to successfully depict Negro character. Another element in the author’s success is a technique which he has modified to his own use, that of the “hard-boiled” school. This technique, despite its negative philosophical basis, is highly successful in conveying the violent quality of American experience—a quality as common to Negro life as to the lives of Hemingway characters.17

In one of two columns devoted to Zinberg in the African American newspaper Pittsburgh Courier, the editor George Schuyler wrote,

Len Zinberg, a young white author, has written a novel . . . which . . . is superior on several accounts to Richard Wright’s Native Son. . . . Zinberg’s Negroes are not caricatures as were Wright’s. The red blood of authenticity pulsates through all of them. The Harlem jive is as realistic as it could possibly be. The picture of Harlem and the plight of its denizens, of all Negroes, is impressively authentic. . . .

[The protagonist’s] sweetheart . . . is one of the finest female Negro characters yet created as characteristic of the modern age . . . far above the . . . liquor-sated Bessie of Native Son.18

In the era of the antifascist crusade, efforts by Euro-Americans to delineate Black life from an antiracist standpoint were often applauded by African American intellectuals. The situation would shift dramatically after the 1967–68 controversy about William Styron’s Confessions of Nat Turner.19

During World War II, Zinberg served in the Army Air Corps from 1943 to 1945, rising to the rank of sergeant and spending most of his time in southern Italy. He was a correspondent for Yank magazine and won a Twentieth Century Fox Film Literary Fellowship award that brought him to Los Angeles for 1945–46. At the same time, Zinberg began contributing to the New Yorker, publishing a dozen and a half stories between 1945 and 1947. A number of these addressed the problem of the adjustment of ex-servicemen to the postwar climate and satirized both ultramasculine behavior and racism. Before the war, Zinberg held membership in the Communistled League of American Writers; afterward he was active in the Communist-influenced National Council of the Arts, Sciences and Professions.

In the late 1940s, he published two more novels under his own name, including a radical one about the Depression-era Left, Hold with the Hares (1948). In this novel, the central character, Steve Anderson (the name anticipates one of Zinberg’s later pseudonyms, Steve April), is a working-class WASP aspiring to a career in journalism. Steve’s heart is with the Left, but he continually rationalizes the opportunistic choices he makes in the years between the Depression and World War II, under the delusion that, once he becomes successful, he will have the power to say what he “truly” thinks and will have some influence. Along the way, Steve meets several Jews who have responded to their Jewish identity in different ways, although anti-Black racism is a touchstone in each instance. One Jewish friend has assimilated simply to remove an obstacle blocking his career, and he frequently uses racist epithets; another, from the South, affirms his Jewishness, but he does so by refusing to fight the Jim Crow system because he does not want to reinforce the southern stereotypes of Jews, including the one of the Jew as a radical troublemaker.

Both of the Jews are doppelgängers, reflections of Steve’s own political opportunism, and Steve likes them because their behavior confirms rather than challenges his own, although clearly the author Zinberg does not like them. What turns Steve around at the climax of Hold with the Hares is the influence of Pete Wormser, a revolutionary white sailor of unstated ethnicity who first fights with the International Brigades in Spain and then with antifascist partisans in World War II; finally, Pete travels to the Carolinas with Operation Dixie, an effort of the Congress of Industrial Organizations (CIO) to organize Black mill workers.

This section features a shootout with a racist, antiunion lynch mob in which Pete’s Black comrade Oliver—whose name suggests Oliver Law, the African American martyr of the Abraham Lincoln Brigade in Spain—is killed. Pete then flees to New York and goes underground. Although the Communist Party wants Pete to return to stand trial, Pete feels he would have no chance in a southern court. Thus, in events somewhat based on those of Communist union leader Fred Beale and the 1929 Gastonia, North Carolina, textile strike, Pete decides to escape to Europe. At this point Steve quits his big-time journalism job and, breaking with his past, sneaks Pete out of the country. In the final pages of the book, Steve launches a new life as a radical writer by taking over a small-town newspaper that was being run by an aged member of the Industrial Workers of the World, in order to fight a kind of guerrilla war against the capitalist system.

The novel can perhaps be read as a psychohistory of Zinberg. Using the extent of opposition to anti-Black racism as a constant litmus test for one’s morality, Zinberg rejects the possibility of presenting a protagonist who finds self-realization as a Jew, because he feels, and the novel suggests, that there were no individuals who joined the vanguard of the antiracist struggle on the basis of their Jewish identity. Zinberg thus, through his surrogate Anderson, opts for a proletarian internationalist identity, although apparently, in his support of Pete’s flight, he indicates a preference to act as a radical free agent rather than a disciplined Party cadre.

With publication of the paperback crime novel The Woman Aroused in 1951, the same year the Communist Party leadership was jailed under the Smith Act, Zinberg became reborn under the name Ed Lacy to protect himself from blacklisting and harassment. As early as 1946, he had been named in a New York Times article reporting on allegations of Communist influence in a New York post of the American Legion.20 Never again, during the next two decades, did he refer to his earlier career or earlier novels in autobiographical statements or in biographical information provided for book jackets. His multiple identities were not even known to most of his left-wing friends from the literary workshops and discussion groups hosted by editors of the Communist journal Masses & Mainstream that he attended at the home of Dr. Annette T. Rubinstein, a blacklisted school principal, throughout the 1950s. Len Zinberg was married to an African American writer, Esther Zinberg (1910–83), who contributed stories as Esther Lacy to the New Yorker, the Negro Digest, the Baltimore Afro-American, and the Contemporary Reader (published under the auspices of the Writing and Publishing Division of the New York Council of the Arts, Sciences and Professions in the early 1950s). Esther Zinberg was also an office worker and was employed for some years as a secretary at the Yiddish Communist newspaper Freiheit. The decision of the interracial couple to adopt a child was another reason for Len to guard his new professional name from any linkage to his political past in the era of red-baiting.

In the 1950s and 1960s Zinberg as Lacy became distinguished among mystery writers for his use of African American characters as protagonists, including two series characters, Toussaint Marcus Moore and Lee Hayes. A third series, which features the character Dave Wintino, includes Lead with Your Left (1957) and Double Trouble (1965). Wintino is part Italian American and part Jewish American and has a Black police partner. Radical politics are pervasive in the Lacy novels; Zinberg was the main opponent among hard-boiled mystery writers to the ultra-reactionary author Mickey Spillane and Spillane’s red-baiting private eye, Mike Hammer. Sin in Their Blood (1952), his second novel as Lacy, depicts a right-wing organization that is blackmailing African Americans who are trying to “pass.” Go for the Body (1954) tells of the interracial marriage of a Black boxer who lives in exile due to racism in the United States and of a scheme to strike a blow against elements of Italian and German fascism that are organizing for a postwar comeback. A Deadly Affair (1960) and Sleep in Thunder (1964) treat racism against Puerto Ricans. The Napalm Bugle (1968) attacks the U.S. government’s role in Vietnam, and Breathe No More, My Lady (1958) favorably depicts a blacklisted radical professor, formerly a professional boxer. Zinberg also published hundreds of short stories in various mystery, pulp, and popular magazines.

The shift from novels in the proletarian tradition to pulp fiction by Lacy was more a matter of entering the mass market than a change in his form or ideology. In all phases of his career Zinberg’s disconcerting irony and multilayered perspectives challenged prevailing constructions of racial and ethnic identity, and especially white male pretensions to ultramasculinity. The post–World War II effort to mask his earlier Communist persona actually functioned to heighten and complicate his approach to such constructions. Starting with his pieces in the New Yorker, Zinberg turned his skills to capturing the nervousness of the post–World War II and Cold War cultural climate. For example, in his second work of pulp fiction, Sin in Their Blood, Lacy rewrites Hemingway’s modernist classic, The Sun Also Rises (1926), for a new age.

Lacy’s hero, Matt Ranzino, like Hemingway’s Jake Barnes, emerges from a war—in this case the Korean War—with a mysterious wound. The doctors in the hospital insist that Ranzino, a former private eye, is cured, yet he continues to believe that he has symptoms. His friends are distressed about his condition, and his former girlfriend, now the mistress of his ex-partner, asks, in a reference to Jake Barnes’s emasculation, “God, Matt, you weren’t wounded there?”21

Matt was not; but his attitude toward women has changed, and he sees the world of the 1950s through new eyes. He is disgusted that his former partner has taken on a “new executive look” and has turned the detective agency into a red-baiting/blacklisting enterprise along the lines of Red Channels. The unnamed modern city he surveys, like T. S. Eliot’s London, has became a commercialized wasteland: “I took in the skyscrapers, the movie houses, the gin mills, the bookie joints that passed as cigar stores, the radio station tower that disappeared into the blue sky, a modern monument to nothing. I watched the people hurrying by, the crowded restaurants and orangeade stands, the heavy traffic—and I knew the street didn’t mean a thing to me any more.”22

Events in the novel, though, force Matt out of his lassitude as he decides to combat the very detective agency for which he had once worked. Haunted by the mass murder he has witnessed in Korea, he refuses to cash in on his veteran status by playing the patriot. He finds himself no longer comfortable with the ideology of toughness to which he once adhered. Even more astounding, for a novel published in 1952, he is drawn to a woman who talks of the need for equal rights, dresses only to please herself, and makes him share the housework. Yet Matt must fight back in an effort to resist the triumph of this new and corrupted wasteland. In contrast to his onetime mentor Hemingway, who draws on the metaphor of the bullfight to promote the need for grace in the face of eternal meaninglessness, Lacy uses a boxing match—the exercising of skill in combat with human opponents. The need to survive and win rekindles Matt’s memory of his old boxing coach, Pops—a moral and socially conscious alternative to the champion of the bullfight ethic, Papa Hemingway.

Twelve years after Sin in Their Blood challenged the Hemingway ethic, Lacy published a full-blown attack on the bullfighting paradigm as an elaborate fraud. Moment of Untruth, set in Mexico rather than Hemingway’s Spain, depicts a Black private eye who exposes a charlatan matador, Cuzo, an Indian, notorious for his womanizing and macho antics. Once exposed, the bullfighter commits suicide—an apparent commentary on Hemingway’s death the year before Lacy’s book was published. Like Lacy’s other books, Moment of Untruth is a troubled study of the difficulty of a modern sensibility coping with the myths of bourgeois society. His Black private eye (this time it is Toussaint Marcus Moore), a target of racism in the United States, is told that he will encounter “no color problems” in Mexico.23 Instead, he finds that he is frequently perceived as if he were a white man and he needs to be repeatedly educated regarding his American chauvinism.

Even more disconcerting, Toussaint’s task is to discredit a pure Indian, the bullfighter Cuzo, who is known as “El Indio,” a member of the bottom rung of the racial hierarchy in Mexico, even as he, Toussaint, walks a sexual tightrope between two white women. One is a masculinized scientist specializing in poisonous snakes; the other, a blond bombshell with big breasts who seems to stalk Lacy characters throughout all his books.

In the last pages of the novel Toussaint painfully reflects: “For all my hatred of Cuzo, I knew he was born a slave and only generations removed from slavery. As an Indian in Mexico he faced the same general problems I had in the States. I could understand only too well what made him tick. . . . I [had] this terrible feeling I was being an Uncle Tom, doing the white folks a favor, somehow, by knocking off El Indio. It was driving me crazy. . . the idea that I was betraying my color.” Toussaint’s final thoughts, then, are far from triumphal at his successful resolution of the case. They show him reflecting an unhappy consciousness resonating with the author’s awareness not only about contradictions of racism in a capitalist society; the passage also suggests that Lacy is disturbed by his participation in the mass culture industry, which by its nature dilutes and compromises the radical sensibility he aspires to impart to his writing. This melancholy mood, a sense of historic entrapment joined with a desperate need to fight on nonetheless, is characteristic of the legacy of the antifascist crusade in U.S. literature.

Many obscure careers in literary radicalism such as Zinberg’s are evoked in Trinity of Passion, with the aim of deepening and complicating rather than creating a counterparadigm to the past five decades of scholarship about the U.S. literary Left. The marvelous founding studies tended to treat World War II as a sad coda: “The Long Retreat,” in Walter B. Rideout’s The Radical Novel in the United States: Some Interrelations of Literature and Society, 1900–1954 (1956); “Disenchantment and Withdrawal,” in Daniel Aaron’s Writers on the Left: Episodes in American Literary Communism (1961); and “The Politics of Collision,” in James Burkhart Gilbert’s Writers and Partisans: A History of Literary Radicalism in America (1968). A few older books examine the literature of the Spanish Civil War in isolation from other U.S. writings of the Depression era to achieve a sustained analysis of the genre, sometimes in an international context.24 Most books about radical fiction published since the 1970s are informed by theoretical perspectives and focus on the 1930s; none substantially takes up the broader Left in World War II.

In 1996, Michael Denning’s The Cultural Front: The Laboring of American Culture in the Twentieth Century contributed a dramatic shift in perspective engaging a spectacular sweep of cultural references. Although Denning did not treat World War II as a discrete moment, he included a positive view of cultural workers of the 1940s in this treatise on the long-term liberating effects of Popular Front culture. Subsequent to Denning, and with comparable sympathies, several persuasive books examining the African American cultural Left have incorporated components of the 1940s into their narratives: Bill Mullen’s Popular Fronts: Chicago and African-American Cultural Politics, 1935–46 (1999); James Smethurst’s The New Red Negro: The Literary Left and African American Poetry (1999); and Stacy I. Morgan’s Rethinking Social Realism: African American Art and Literature, 1930–1953 (2004). Earlier, Susan Schweik’s A Gulf So Deeply Cut: American Women Poets and the Second World War (1991) had brilliantly explored the experience of war as an ideological construct in relation to gender.

There are additional studies to which I am particularly obliged that speak to aspects of culture and politics in World War II. I read Chester E. Eisinger’s Fiction of the Forties (1963) as an undergraduate and was enraptured by his narrative sweep of politics and literature. I was also taken with the photographs on the cover of the paperback edition of the faces of Irwin Shaw, Budd Schulberg, Nelson Algren, James T. Farrell, and others who imparted an aura of realist and naturalist writers earnestly engaged with ideas. To George Lipsitz’s Rainbow at Midnight: Labor and Culture in the 1940s (rev. ed., 1995) I owe many methodological debts, including Lipsitz’s expansive notion of the category of class.25 I much admire Andrew Hemingway’s Artists on the Left: American Artists and the Communist Movement, 1926–1956 (2002) for its holistic approach and the author’s effort to restore to the Communist movement the credit it merits without blurring its political flaws to the reader. Both Andrew Hemingway and I see the Popular Front as the continuation of a troubled tradition in new forms rather than a genuine solution to earlier predicaments.

There also exist numerous scholarly works that do not engage literature but nevertheless reflect on writers in relation to the major political controversies of the Spanish Civil War and World War II. The dispute over the 1939 Hitler-Stalin Pact and the political cost of later delusions about the USSR have been traced in works such as William L. O’Neill’s The Great Schism: Stalinism and the American Intellectuals (1982). The political somersaults of the Communist movement before, during, and after the 1941 German invasion of the USSR were derided in Irving Howe and Lewis Coser’s The American Communist Party: A Critical History (1957). Even the 1946 literary controversy surrounding screenwriter Albert Maltz, a critical episode in Trinity of Passion, has been a principal focus of scholarship since it was reported forty-five years ago in Aaron’s Writers on the Left; most recently it was a centerpiece of Ronald Radosh and Allis Radosh’s history, Red Star over Hollywood: The Film Colony’s Long Romance with the Left (2005). Several of these books attack Communist foibles with such prosecutorial zeal that it is hard to see the reasoning by which intelligent, humane, and talented writers would choose to devote themselves to what is painted as predominantly a foolish and corrupt cause. But I do not dispute the rudimentary facts they present.

An exceptional work of political history that has not received attention commensurate with its originality is Frank A. Warren’s Noble Abstractions: American Liberal Intellectuals in World War II (1999). Warren draws a distinction between the Popular Front of the late 1930s and the post-1941 confluence of liberals and Communists around the antifascist crusade in World War II. Neither, of course, was a genuine Popular Front in the sense of constructing a form of organization-to-organization unity achieving governmental rule. But Warren observes that the World War II coalition gave a lesser role to the political influence of the Communist Party. This is partly because the Communists, contrary to their image as extremists in the popular mind, repeatedly went farther to the right than many liberals in their idealization of the Democratic Party, their hostility to the militant wing of the African American civil rights movement, and their inclusion of rivals (Norman Thomas Socialists and Trotskyists) into their amalgam of a “fifth column” that needed to be governmentally suppressed. Noble Abstractions is not, however, just one more book about Communist blunders; Warren’s principal attention is devoted to the liberals’ own illusions that World War II was somehow “a democratic revolution” and an international civil war between democracy and fascism.

Trinity of Passion, in contrast, is about writers and literary trends, where there was a stronger continuity over the decades for those who perceived Spain and World War II as stages in an elongated contest to transform capitalism by defending it against the internal and external forces of the Far Right. Still, the antifascist crusade in culture was far from seamless, even for those pro-Communists who are the subject of this study. The belief systems of the writers were perpetually challenged by calls to alternately embrace and then flay liberal allies; to instigate and then oppose strikes; to urge, then resist, and then again urge U.S. governmental action against fascism; and to identify racism in the United States with fascism abroad, then to subordinate struggles against the former for the sake of national unity against the latter. With the exception of the unmitigated threat posed by the Nazis, the social and political terrain was fraught with contradictions. None of these obviated the need to destroy fascism by military force, but they did pose questions about the ideological and strategic aims of the Allies.

The capitalist democracies were compromised by their colonial empires, class oppression, and virulent racism, and their Soviet partners masked a brutal dictatorship behind the guise of “socialism.” Moreover, the war in the Pacific had a disturbing racial character. By and large the Communist-led wing of the antifascist crusade, particularly strong in literary circles, demanded an exacting loyalty to shifts in Soviet policy that would permanently taint Communist Party claims to be consistently prolabor and antiracist. In 1946, in the course of a bitter postwar debate in the pages of the New Masses about the slogan “Art as a Weapon,” the Communist Party’s political and cultural leadership stuck fast to its tradition of judging literature by current Party policy; thus the fault lines first exposed by intra-Left debates in the 1930s were visibly deepened.26

Most novelists in the pro-Communist tradition sought to accomplish meaningful ideological work in their creative efforts. Many drew considerably on models of the realist and naturalist schools and sporadically on modernist strategies, to restore historical consciousness to the reader by reproducing the forces shaping character, society, and belief. Their aim of dereifying the reader’s mental world is an honorable artistic objective, but creative work is always revelatory in aspects unexpected and even unintended by its authors. That is why a cardinal concern of Trinity of Passion resides beyond formal ideology. Although a comprehensive reconstruction of all of the elements shaping a writer’s consciousness is unattainable, the discernment of the intricacies of his or her political passions can modify, enrich, and challenge earlier interpretations of novels, poems, and plays. Traces of the piercing convictions of the day can also be detected in works published decades later, frequently in forms that are masked and modified.

More than fifty years later, signs of the literary origins of Len Zinberg and many others who launched careers in the antifascist era are far less decipherable than those of writers who came into their maturity during the 1930s. Writers of the Depression forthrightly declared their aims of producing “revolutionary poetry,” “workers theater,” and the “proletarian novel.” Writers of the 1940s were more integrated into mainstream and popular literature.

The argument of Trinity of Passion, as is that of Exiles from a Future Time, is not that Communism has been the secret glue of U.S. literature in the 1930s, 1940s, and 1950s. To the contrary, Communism, or even political commitment in general, is by itself a deficient and distorting prism through which to view the narrative imagination. Too often a preoccupation with Communist affiliations leads to the deductive fallacy of making presumptions about the artistic process according to supposed political loyalties of authors. Trinity of Passion intends to offer a judicious assessment of the intricacy of the lives of those writers in which a shared yet individualized political commitment played an indispensable part. It also aims to consider the implications of the transit through the antifascist crusade that are dispersed across the horizon of mid-twentieth-century literary history. To that end, the account begins with literature that responded to the founding moment of the antifascist crusade, the civil war in Spain, and proceeds to several fronts of World War II.