4

A Rage in Harlem

THE BLACK CRUSADERS

In February 1942, the Reverend Adam Clayton Powell Jr. (1908–72), a flamboyant Harlem politician nicknamed “King of the Cats” by his biographer, launched an iconoclastic African American newsweekly that had Far Left politics.1 The People’s Voice was published in an office atop the Woolworth’s Department Store at 210 West 125th Street, across the street from the Apollo Theater. The paper’s editorial manifesto called World War II “one of the great crossroads of history” and invoked the obligation of all people to forge a unity against fascism. Indeed, the editors had earlier called their mission “The Crusade”—with the hope that it would advance in the tradition of the abolitionist Frederick Douglass, under the leadership of editor-in-chief Powell, who was elected to the New York City Council in 1941 and the U.S. Congress in 1945.2

In this spirit the People’s Voice editors and staff crafted the following covenant: “We are men and women of the people. The people are ours and we are theirs. We respect no authority except their authority. We obey no mandate except their mandate. We look to no one to judge us except—they the people!” To underscore its pro-socialist perspective, the editorial went on to state, “THIS IS A WORKING CLASS PAPER. We are a working class race. We pledge to the trade union movement our fullest cooperation.” The editors righteously boasted that they would eschew coverage of crime, the mainstay of most urban newspapers. Instead, “we . . . will fight to break down the walls of our ghetto by crusading for lower rent, better housing conditions, more and better health facilities, removal of restrictions against Negroes in the secondary school system . . . a just quota of jobs in all city, state and federal agencies.”

The manifesto’s political stance was slightly to the left of the Popular Front in its conspicuous stress on class and race. Thus it is surprising that the paper was silent regarding the pivotal war issues of Double V and the segregated military. On domestic issues the editorial was precise and programmatic, but of World War II the People’s Voice waxed rhetorical, affirming a capacious but ultimately evasive vision: “We believe firmly that this is the people’s hour to make democracy real and thereby make it world triumphant. If this is not done, we may lose this war. If this is not done, even though we win it, we lose the peace. . . . We are against Hitlerism abroad and just as strongly against Hitlerism at home.”3 Such a formulation camouflaged an ambiguity about what precisely constituted “Hitlerism” in Harlem and what might eventuate if antiracist activity should hamper war production for the anti-Nazi military effort in Europe. Nevertheless, it effectively created space in the pages of the People’s Voice for a plurality of approaches focusing on, but also extending slightly beyond, the Popular Front.

Powell to a certain extent resembled other independent leaders of the African American Left in the early 1940s, such as Paul Robeson, Langston Hughes, and W. E. B. Du Bois.4 The three were strongly attracted to the Soviet Union and variously sympathetic to the Communist Party, but they were uneasy with the Party’s policy formulation that “the greatest service that can be contributed to Negro rights is unconditional support of the war, without which equality and freedom is impossible for any people.”5 Accordingly, versions of both Double V and the Communist Party’s position appeared in the paper’s pages.

Backing for the People’s Voice came from several entrepreneurs associated with Harlem’s famed Savoy ballroom. From the time it opened in 1926 on Lenox Avenue between 140th and 141st streets, the Savoy welcomed integrated dancing to swing and jazz orchestras. Moe Gale (born Moses Galewski), one of two Jewish brothers who founded the Savoy, gave financial support to the paper, while Charles Buchanan, a Black Harlem real estate broker who managed the ballroom and was an ally of Powell’s, was the publisher.6 The paper was printed on the presses of PM, a daily Left-liberal paper founded by the millionaire Marshall Field III in 1940.7

Equally vital to the paper’s success was the technical support Powell received from his African American confidants in the Communist Party. Powell had been friendly to the Communists since the mid-1930s, welcoming them to the Abyssinian Baptist Church where he had succeeded his father as pastor. The church was the largest Protestant congregation in the United States, boasting more than 15,000 members.8 Powell was a self-promoting left-wing maverick, but his prolabor activities often coincided with the positions of the Communist Party. He had tended to be antiwar during the Hitler-Stalin Pact but became ardently prowar after Germany’s invasion of the USSR.9

The Communist intellectual most pivotal to Powell’s People’s Voice was the brilliant Harvard-educated Black lawyer and Party leader Benjamin Davis (1903–64). Davis had ample journalistic experience as editor of the Communist Party’s Harlem Liberator and also as a member of the editorial board of the Daily Worker. He collaborated frequently with Powell in the 1930s, although they had sporadic disagreements. In 1943 Powell launched a campaign for Congress and urged that Davis be elected his successor on the New York City Council, which he was. Davis was reelected in 1945 in a landslide victory that united the Blacks of Harlem with Leftists in working-class neighborhoods across Manhattan. In 1949, two years after Powell broke with the Communists and the People’s Voice collapsed, Davis was sentenced to five years in prison under Smith Act charges of conspiring to teach the overthrow of the government. During his confinement in the federal penitentiary in Terre Haute, Indiana, until 1955, Davis wrote his autobiography, Communist Councilman from Harlem, but federal authorities would not release the manuscript until after Davis’s death in 1964, when it was published.10

Another member of the insurgent African American left-wing brain trust that Powell attracted to the People’s Voice was Doxey Wilkerson (1905–93). Wilkerson was a onetime doctoral student at the University of Michigan who joined the faculty of the School of Education at Howard University in 1935. He then became a researcher and cowriter of Gunnar Myrdal’s An American Dilemma (1944) and served as vice president of the American Federation of Teachers from 1937 to 1940. Wilkerson joined the Communist Party in 1943 at the time he became a journalist for the People’s Voice. He rose immediately to the post of executive editor, which he held for the next four years. Subsequently he became a leading Communist Party educator until he resigned from the Party in 1957. Completing his doctorate at New York University in 1959, Wilkerson tried teaching at a college in Texas, but red-baiters forced his resignation within a year. He spent the last decade of his academic career, 1963 to 1973, as chairman of the Department of Curriculum and Instruction at Yeshiva University in New York.11

Another notable Communist writer for the People’s Voice was Max Yergan (1892–1975), a former activist in the Young Men’s Christian Association who had lived in India and Africa. Joining the Communist Party after visiting the Soviet Union in 1936, Yergan became a leader of the National Negro Congress and the Council on African Affairs, as well as a Harlem celebrity. In 1948 he suddenly lurched to the right; he first metamorphosed into a hired informant against Communists and then became a pro-apartheid lobbyist.12

The first phase of recruiting writers for the People’s Voice entailed a raid on the Amsterdam News, the established Harlem weekly that had long been denounced by Powell and the Left for its use of sensational headlines and the negligible attention it paid to social issues. Most significant among the talented journalists who made the switch was the distinguished writer Marvel Cooke (1903–2000), who had been the first woman reporter on the Amsterdam News in its forty-year history. Hired in 1931, Cooke had been drawn to the Communist Party in 1935 through her collaboration with Black Communists such as Benjamin Davis in activities supporting the strikers of the American Newspaper Guild. She joined the Party the following year but kept her membership secret for fear of losing her job. After leaving the Amsterdam News in disgust over its sensationalist coverage of crime, Cooke became the de facto managing editor of the People’s Voice throughout most of its existence, although sexism prevented her from holding the official title.

During the Cold War Cooke made front page news in the New York Times when she was subpoenaed by Joseph McCarthy in 1953 to testify about her People’s Voice activities. McCarthy asked Cooke questions such as “Were you known by the other employees [at the People’s Voice] as ‘Mrs. Commissar’?” and “It has been testified by a number of witnesses that you held a position so high that you gave orders to the Communist National Committee. Would you tell us whether that testimony is true?”13 Like most Leftists who did not want to be legally coerced into “naming names,” Cooke pleaded the Fifth Amendment and declined to answer.

This public assault on Cooke transpired at the very time when alleged Communists were being fired, beaten up, driven into exile, and imprisoned and when the Rosenbergs were executed. Her subpoena, and the overwrought testimony of a few former People’s Voice staff members who claimed that the paper was Communist-controlled, in all likelihood put a permanent damper on the willingness of people connected with the newspaper to discuss their activities and personal associations in subsequent years. Cooke, however, remained undaunted in her Communist commitment.

From 1950 to 1952 she was a reporter and feature writer for the Daily Compass, which was one of several unsuccessful efforts to continue the Left-liberal tradition of PM. Its most well-known reporter was the radical I. F. Stone (1907–89). In 1953 Cooke became the New York director of the Communist-led Council of the Arts, Sciences, and Professions. In 1970, at the request of the Communist Party, she became coordinator of New York activities for the National United Committee to Defend Angela Davis, the Communist philosophy professor who was falsely accused of involvement in a courthouse shooting in Marin County, California. Until 1989, Cooke was vice-chair of the National Council of Soviet-American Friendship.14

Conspicuous among the talented left-wing artists who congregated around the People’s Voice was the noted cartoonist Oliver “Ollie” Harrington (1912–95), creator of the character “Bootsie.” On any given Wednesday, when the People’s Voice appeared, one might find an article by Paul Robeson, a poem by Langston Hughes, an excerpt from a work by Richard Wright, an essay by Alain Locke, or a theater review by Owen Dodson (1913–83), all of whom also appeared in the NewMasses and sometimes in the Daily Worker. With the onset of the Cold War, Wright moved to Paris, Robeson’s passport was revoked, and Dodson pulled back from the Left. Harrington, at that time a political independent whose cartoons during World War II reflected a Double V outlook, moved to Paris in 1951. In 1961 he moved to East Germany, where he lived for the rest of his life, sending his cartoons to the U.S. Communist press for publication after 1968.

At the climax of its six-year run, the People’s Voice was looking pretty Red. Powell would often be away on business, delegating day-to-day affairs to a Communist who was executive editor, Doxey Wilkerson. The duties of managing editor—including the supervision of all writing—were under the direction of another Communist, Marvel Cooke. And Communist Party official Ben Davis had his own column, in which he aggressively promoted Communist positions. FBI operatives frequently questioned staff members in the hope of uncovering Communist control of the publication, but the autocratic Powell was the paper’s unifying personality.15 While all writers adhered to the “crusade” championed in the People’s Voice, not all staff members had political associations as conspicuous as those of Wilkerson, Cooke, and Davis.

Among the cadre of defectors from the Amsterdam News to work for the People’s Voice was an aspiring young writer named Ann Petry (1908–97), who was born Ann Lane in Old Saybrook, Connecticut. Petry was proud that four generations of her family hailed from Connecticut, but she felt that her “outsider” status as an African American woman gave her a “tenuous, unsubstantial connection with New England.” As a young girl she felt a strong identification with Jo March, “the tomboy, the misfit, the impatient quick-tempered would be writer” in Louisa May Alcott’s Little Women (1868–69). Fairy tales and mystery stores enriched her imagination, as did family stories that bequeathed to her a “powerful oral-narrative tradition.”16 Some of these were about her maternal grandfather, who had escaped from slavery, and her father, Peter Clark Lane Jr., who had defied racist threats when he opened Old Saybrook’s first black-owned drugstore in 1902. Many more stories came from uncles who had lived all over the world and worked at many jobs. One had served in the Spanish American War, and another had been sentenced to five years on a Georgia chain gang. Petry’s mother, Bertha James Lane, was one of three sisters who had refused the role of housewife to become successful businesswomen who were financially independent; Petry’s mother’s company was called Beautiful Linens for Beautiful Homes.

At age four Petry accompanied her older sister to first grade; no one asked her to leave, so she commenced an early education. Although Petry was already writing stories and plays in high school, she chose to follow her father’s occupation by attending the Connecticut College of Pharmacy, from which she graduated in

ANN PETRY was a radical journalist and activist in Harlem in the 1940s who became an outstanding novelist and short story writer. (Photograph by Carl Van Vechten; courtesy of the Van Vechten Trust, Lancaster, Pa., and the Carl Van Vechten Collection, Yale University)

1931. Thereafter she worked for nearly seven years in the two family drugstores. During this time she met George David Petry, originally from Louisiana, on a trip to Hartford. In 1938 they were married. They moved to New York City, where George lived, to test their literary inclinations.

Petry quickly found a job with the Amsterdam News selling space for the advertising department, while her husband worked in a Harlem restaurant and attempted to write mystery stories before he eventually turned to working as a writer on the Federal Writers Project and then in marketing. A year later Petry published her first piece of fiction, a pulpish story, “Marie of the Cabin Club,” under the pseudonym Arnold Petri, in Baltimore’s left-wing Afro-American. The story is noteworthy for its anticipation of Petry’s evolution by the time of the publication of her most popular novel, The Street (1946). Like many episodes in The Street, the setting in “Marie” is an interracial nightclub recalling the Savoy ballroom and features a thriving African American trumpet player who takes the heroine for a ride in his fancy car. There are also stock characters from standard spy stories, including a sinister Englishman working for the Japanese government and a mysterious white woman who turns out to be a secret agent for the French. The former elements, closer to Petry’s own experience, would intensify, while the latter would vanish in her later fiction.17

In 1940 Petry joined the American Negro Theater, of which she remained a part for more than two years. During the first year, she played Tillie Petunia three nights a week in Abram Hill’s radical critique of the Black middle class, On Striver’s Row (1940). Among the left-wing African American actors and actresses associated with the American Negro Theater in the 1940s were Ruby Dee, Ossie Davis, Alice Childress, Canada Lee, Sidney Poitier, Frank Silvera, and Harry Belafonte. Concurrently, Petry furthered her studies in painting and the piano. During 1941 she joined her onetime Amsterdam News colleague Marvel Cooke on the staff of the People’s Voice.

While journalism at the new radical publication provided novel and edifying adventures, Petry still yearned for success as a fiction writer. She enrolled in a Columbia University writing class in 1942 and then a writers’ workshop in 1943, both led by Mabel Louise Robinson. Her next short story, “On Saturday the Siren Sounds at Noon,” was published in the Crisis in 1943. Although never reprinted, it constitutes another critical marker en route to The Street. Both the novel and the story focus on impoverished Harlem residents struggling against the economic odds and emphasize the special costs to children. In the short story, an exhausted Black worker returns home on a Monday to learn that his three children have been trapped in a fire in his apartment building; one is killed and two are injured. On the following Saturday morning he learns that the three youngsters had been locked in the apartment while his wife was with another man. In a daze he strangles her and then leaves for work in the late morning. When an air raid siren sounds at noon, the horror of the crime that he perpetrated is pulled to the surface of his consciousness, and he commits suicide by jumping in front of a subway train.18

The idea for “On Saturday the Siren Sounds at Noon” originated in a newspaper article that reported that two children had been burned to death while both parents were at work. Petry added the adultery and the revelation of the wife’s betrayal as the turning point in the story, and she used a flashback technique in which the guilt-ridden husband is prompted by the noonday siren to recall the events precipitating the murder.19 The story attracted the attention of an editor at Houghton Mifflin who encouraged Petry to plan a novel and apply for the company’s literary fellowship.

Petry competed for the fellowship after leaving the People’s Voice in 1944 and received $2,400 in 1945. When she reworked some of the material of her story into The Street, Petry retained mainly the discovery of sexual betrayal and a climactic Black-on-Black killing. She departed markedly, however, from the story by complicating gender roles in ways that contested the customary male and female stereotypes in “On Saturday the Siren Sounds at Noon.” The Street presents a cheating Black woman, Jubilee, but the woman defends herself with a knife against her outraged lover, Boots Smith. Later Boots Smith becomes the betrayer of another self-reliant woman, Lutie, and he ends up the victim of her murderous rage.

“TALENT AS A WEAPON”

Petry was fully committed to the People’s Voice throughout the 1940s, ideologically and as an activist. During her two-year tenure on the paper’s staff, she was editor of the women’s page, a reporter for stories dealing with the Harlem community as well as national protests, the author of a weekly column of announcements and gossip called “The Lighter Side,” and the editor of the politically focused “National Roundup” of news.20 In “The Lighter Side” column Petry’s maturing familiarity with the Left was in evidence as she publicized and commented on cultural, social, and political events held under the auspices of the anticolonialist Council on African Affairs and at radical venues such as Café Society. Among the many left-wing writers, artists, and musicians whose activities were reported in “The Lighter Side” were Anton Refregier, Leonard Zinberg, Josh White, Earl Robinson, Paul Robeson, Aaron Douglas, Andy Razaf, Elizabeth Catlett-White, Augusta Savage, Jacob Lawrence, Langston Hughes, Sterling Brown, Angelo Herndon, and Theodore Ward.

Politically parallel to Petry’s journalism was her role in organizing Negro Women, Inc., in May 1941. Sometimes shortened to Women, Inc., the group was described by Petry in the People’s Voice as the women’s auxiliary of the People’s Committee, in which any woman is welcome if “you believe in a fighting program for the rights of Negro women.”21 The People’s Committee had been set up by Adam Clayton Powell with his left-wing allies to quickly mobilize people in Harlem to protest and picket. The FBI carefully monitored the organization because of the central roles played by pro-Communists such as Ferdinand Smith, Max Yergan, Audley Moore, Benjamin Davis, and Theodore Bassett.22 Petry remained an officer of Negro Women, Inc., until 1947. Starting in 1942 her community activism broadened to include collaborating with the Laundry Workers Joint Board to devise programs for the children of laundry workers. In 1943 she became assistant to the secretary of the Harlem-Riverside Defense Council.

However, in interviews with and autobiographical statements made by Petry after the onset of the Cold War, references to her engagement in the Harlem “crusade” are sparse and entirely depoliticized. She customarily gives the impression that her work at the People’s Voice was merely a paying job on a traditional newspaper, or she confines her Harlem journalistic experience to the Amsterdam News.23 There are no references to the People’s Committee. Negro Women, Inc., is described by Petry as “a Harlem consumers’ watch group” that provided “working-class women with ‘how-to’ information for purchasing food, clothing, and furniture.”24 In glaring contrast, at the time Petry first came to national attention with the publication of The Street in 1946, she was straightforward about her radical convictions and activities, including her friendly attitude toward the Communist Party. Similar documentation is evident in African American, mainstream, and Left publications prior to 1950.

In a Chicago Defender profile and interview with Earl Conrad in early 1946, Petry is described as belonging “to the great, hopeful phalanx of labor advocates.” When asked what her solution to segregation was, she replied, “The group that would, more likely than any other, solve this question is labor. The labor unions primarily have fought for the Negro interest. If Christianity would be a living thing, it would be all right, but it does not live. The bulk of the population gives only lip service to the thoughts of Christianity. Labor and the Negro must mark off a path to each other.” Petry also insisted that there was not “much difference between the Republican and Democratic parties”; she believed that “a third party” is “feasible” if “the people can find a leader around whom to rally.”25

In an Ebony magazine interview and profile a few months later, Petry is described as “active in fighting for greater social rights and security for women.

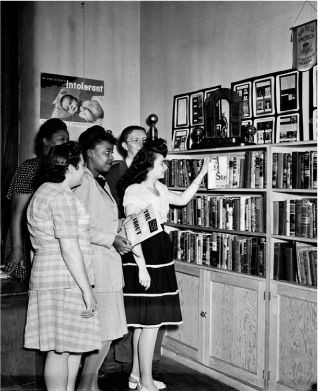

ANN PETRY (third from left) at a meeting of the Laundry Workers Joint Board in 1946. (From the Petry Collection in the Howard Gotlieb Archival Research Center at Boston University)

She is executive secretary of Negro Women, Inc., a kind of pressure group of New York Negro women who are dedicated to advancing the status of Negro women and all women.” Politically, Petry is said to “consider herself a ‘definite progressive’ on political and social matters. She finds the label ‘liberal’ a trifle vague and a little confusing.”26 Two years later, the Progressive Party electoral campaign supporting Henry Wallace for president would be launched, opposing President Truman’s Cold War policies and his domestic anti-Communism.27 However, before then, throughout the era of the Popular Front, the term “progressive” usually meant a radical who was willing to collaborate with Communists and who looked on the Soviet Union favorably as a force for peace and anticolonialism. Pro-Communists and nonpublic Party members sometimes called themselves progressives as well when they did not want to be labeled as Party supporters or members.

Petry first gained notice in the Daily Worker in March 1945, when she was awarded the Houghton Mifflin literary fellowship. She was identified as “executive secretary of Negro Women, Inc.”28 Added attention came after the publication of The Street, her novel about a single mother in Harlem, Lutie Johnson, driven to kill a Harlem nightclub band leader who tries to turn her into a prostitute. In the Daily Worker in March and April 1946, The Street was the subject of a review, a column, and a letter, and Petry was featured in a combination profile-interview. In May The Street was reviewed in the New Masses, and another review appeared in the first issue of the Communist-sponsored Mainstream in 1947.

The most positive commentary on the novel was by John Meldon, a writer who at one time covered waterfront issues, in the Daily Worker. Meldon characterized The Street as a “Harlem Tragedy” that unabashedly exhibits the good, the bad, and the ugly among Harlem residents but also “presents, with a cold and savage logic the underlying economic and social reasons” explaining the various types “who parade through The Street with an ominous tread.” Meldon anticipated a possible criticism by readers of the absence in the novel of any mention of the “progressive movement” in Harlem led by Adam Clayton Powell and Benjamin Davis. He insisted that the book was nevertheless realistic because such forces in Harlem were still a minority and inadequate; therefore many women, like Lutie, would not know to whom to turn for help.29 Shortly after, a letter to the editor praised the novel but contended that “somewhere along the line in 436 pages and in some corner of Ann Petry’s mind there should be minimum knowledge about a developing unity between Negro and white.”30

As it happened, the Meldon review and the letter to the editor appeared as the Party was in the midst of a debate over a New Masses essay by Albert Maltz published in February.31 One of Maltz’s chief antagonists in the debate, Communist literary critic Samuel Sillen, wrote a Daily Worker column linking Petry and Maltz. Sillen pointed out that Maltz had insisted that an artist could legitimately depict one “sector of experience,” such as an impoverished man committing a theft and being sent to prison, without having to include “the whole truth” of the national political situation or introduce into the narrative a council for the unemployed that would save the day. While Sillen concluded that Maltz’s claim had some veracity, he nonetheless felt that Petry confirmed the dangers of Maltz’s view by her omission in The Street of any “genuinely affirmative pressures in the Negro community.”

Sillen admired Petry’s novel in general but believed that her strategy rendered the final conflict in the novel “self-enclosed, circular,” resulting in “awkward and enforced melodrama.” While Sillen did not object to Petry’s writing tragedy, he felt that the climactic “Black-on-Black” violence was unilluminating. In a swipe at both Meldon and Maltz, he concluded that Petry’s art would be superior if she had resisted “the conventionally bourgeois divorce between the sector of experience” and “our total comprehension of reality.”32

Sillen was not linking Maltz and Petry hypothetically. Only a month before his column appeared, the Daily Worker had published writer Beth McHenry’s interview with Petry, in which Petry mentioned that she had been carefully following the debate over Maltz’s essay. The literary perspective embraced by Petry attests to her partisanship of Maltz’s approach, and she appears to offer the opinion that an open debate would enable Maltz’s perspective to triumph. Petry also generously praised Meldon’s “Maltzian” review as “one of the best,” because it went “to the heart of what I was trying to say.” Affirming her solidarity with the Left cultural movement, Petry described her role as an artist as an “emotional arouser” and said that she aimed to write a series of books that would “move [the public] to action.” Yet, aligning with Maltz’s perspective, she indicated some discomfort with the slogan “Art as a Weapon,” which Maltz felt could lead to formulaic writing. As an alternative, Petry stated that she looked on her own “talent as a weapon,” by which she meant that she was equally committed to the use of genuinely artistic methods.

Not surprisingly, Petry told the Daily Worker that she profoundly disagreed with the critics who maintained that her novel would have been more effective if it presented a hopeful ending: “I feel that the portrayal of a problem in itself, in all its cruelty and horror, is actually the thing which sets people thinking, and not any solution that may be offered in a novel.” Regarding The Street, Petry alluded to one of Maltz’s most critical arguments—that the reader does not approach a novel with an empty head. She speculated that most people who would bother to read a novel such as The Street would already hold antiracist sentiments, “but they’ll have to be made to feel—anger, horror, indignation—before they’ll actually move on any program to solve the problem.”

Petry concluded the interview by stating that she was “not affiliated with any party” but regarded this as a “mistake” because she “believes the only way a responsible human being can be an effective one is to join the party of his choice and become involved in its activities.” As an example of her activity, Petry mentioned her job as executive secretary of Negro Women, Inc., “which functions as a progressive community organization in Harlem.” Although Petry announced her intention to eventually move to a small town, she stressed that she was going to combat political isolation by dividing her time so that she “can come across with full-time community activity for at least three months of every year.”33

The next month the New Masses carried a review far more disapproving than any of the commentary in the Daily Worker, a review that addressed problems that had been raised in the critical letter to the editor and the Sillen column. Writing under the pseudonym Alfred Goldsmith, the short-story writer Saul Levitt (see discussion in Chapter 6) linked Petry to Richard Wright, now regarded by the Party as a betrayer of the Left, because of her “opportunism” in the creation of character. Levitt saw the predicament of writing about African Americans as being that an author is faced with the unique complexities of African American life—characters caught between desires to “change” and to “escape,” as well as seething “with the interaction of national and class drives.” Unfortunately, Petry evaded this complex challenge by resorting to a juxtaposition of dark, stereotyped Black male villains and “the two-dimensional effect of an early movie starring Lillian Gish.”

Assuring his readers that he was not demanding that Petry should show “a way out,” Levitt insisted that the character of Lutie should have been more extensively realized. This would allow the nature of Lutie’s individualist desire for escape and the one-sidedness of her “hatred of the tragically malformed personalities around her” to stand out more boldly.34 Like Sillen, Levitt was selling short the capacity of the likely readers of Petry’s fiction to contextualize the action of the text.

A year later, a final evaluation of The Street appeared in the Communist press. In the inaugural issue of Mainstream, a literary journal launched in 1947, African American playwright Theodore Ward (1902–83) included Petry’s novel in a survey of five African American novelists. All five are variously indicted for failing to make the necessary link between the contemporary racist horrors of capitalism and “the new being born within the old.”35 The charge echoed the pivotal issue in the Party’s debate with Maltz over the linking of sectors of experience. More specifically, Ward accused Petry of seeing African Americans “caged in by white prejudice, economic injustice and hate.” Ward called this a vision of “despair” and an example of “burning support of the theory that in America life for the Negro inevitably ends in a cul-de-sac.” Both Levitt and Ward linked Petry to Richard Wright and Chester Himes, but inasmuch as Petry did not explicitly attack the Communist Party, Ward noted that “it should be stressed that unlike Wright and Himes she employs it without political bias.”36

Petry’s final unabashed expression of her politics during the Harlem years appeared three years later. In a photographically illustrated essay about Harlem that Petry contributed to Holiday magazine at the end of the 1940s, she featured photographs of Powell’s Abyssinian Baptist Church (with the caption “Progressive institutions and courageous individuals offer Harlem hope”) as well as of Powell and W. E. B. Du Bois, accompanied by two poems by Langston Hughes. Without mentioning the now-defunct People’s Voice, she repeated its traditional criticism of the Amsterdam News for its headlining of “the ripest scandals and the goriest murders” alongside editorials that are “as sedately written and as innocuous as those in the New York Sun.”

Petry concluded her survey with the description of an invented Black worker named George Jackson as a symbol of the Harlem population. The fictional Jackson was politically educated by Adam Clayton Powell’s 1941 election campaign for the City Council, after which he helped elect Powell to Congress for two terms: “This same George Jackson has twice helped to elect Benjamin J. Davis., Jr., a Communist, to the seat that Powell held in the City Council.” This did not mean that Jackson had actually joined the Communist Party: “The chances are that he voted for Ben Davis because he felt Davis would never sell Harlem down the river.”37 Jackson’s political evolution likely mirrors her own. Moreover, her statement was an implicit act of solidarity with Davis. Petry would surely have been aware that, nine months earlier, six FBI agents had burst into Councilman Davis’s home and arrested him on the charge of teaching the violent overthrow of the U.S. government. Petry’s choice to stress the controversial Ben Davis over Adam Clayton Powell may also reflect her disillusionment with Powell’s shift toward anti-Communism.

It was the bravery and commitment of Ben Davis, not the Communist Party, that shaped her esteem. In all probability, the publication in the Daily Worker of the Sillen column and in the New Masses of the Levitt review alienated Petry from the Communist Party’s cultural milieu. If the two sectarian appraisals of her novel did not do the job, then assuredly she was estranged by Maltz’s humiliating self-criticism only a few weeks after the publication of her interview endorsing Meldon’s “Maltzian” interpretation.38 Her anger was still evident four years later, in “The Novel as Social Criticism,” an essay she published in an anthology called The Writer’s Book (1950). The essay was among the last nonfiction expressions of Petry’s fading commitment to the quasi-Marxist spirit of the World War II era progressive crusade in Harlem.

In her essay, Petry was still unrepentant, and even belligerent, in referring to The Street as a novel of social criticism. Noting that the latest fashion among critics was to condemn novels of social criticism as “deplorable,” she claimed a long and noble genealogy for such literature, extending from the Bible to Willard Motley’s recent Knock on Any Door (1947). Contrary to those who disparaged “propaganda novels,” Petry argued that “all truly great art is propaganda,” and she offered a common axiom of historical materialism: “The novel, like all other forms of art, will always reflect the political, economic, and social structure of the period in which it was created.”

Yet Petry insisted that a social critic need not be a Marxist but merely “a man or woman of conscience.” She quoted Richard Rumbold’s 1685 oration on the scaffold about class oppression, 150 years before Marx, and suggested that the reading public has a psychological need for literature that reminds society of its failings. But she warned of the danger that a social perspective might transform a novelist into a “pamphleteer” and “romanticist.” In a rejoinder to her Communist critics, as well as the critics of Maltz, she repudiated those who demanded the appearance in the text of “a solution to the social problem [the author] has posed. He may be in love with a new world order, and try to sell it to his readers; or, and this happens more frequently, he has trade unions, usually the CIO, come to the rescue in the final scene, horse-opera fashion, and the curtain rings down on a happy ending as rosy as that of a western movie done in technicolor.” This criticism seems a bit unfair when applied to the Communist literary tradition of the United States, but it reveals the depth of her frustration with the critics of her bleak description of Harlem life.39 She then provided a persuasive insight into one of the principal challenges facing all left-wing writers of committed literature, including herself. She pointed out that in indicting society, one must avoid the temptation to place blame totally on social, political, and economic circumstances, lest characters become cardboard due to the absence of “each individual carrying on his own personal battle against the evil within himself.”40 This statement helps explain why Petry resisted creating characters in The Street and her other writings whose views and behavior might be mechanically due to their status as social victims of racism and class oppression.

LUTIE JOHNSON’S WAR

Indications of Petry’s increasingly intricate social vision and approach to literary characterization are discernible in the third and last short story she published before The Street. “Doby’s Gone” appeared in 1944 in Phylon, the magazine founded by W. E. B. Du Bois at Atlanta University four years earlier. It concerns a six-year-old African American girl, Sue Johnson, and her imaginary male friend, Doby. Sue has moved from an isolated rural existence into a small town, and Doby accompanies her everywhere. As the only Black child in the town’s school, Sue is subjected to expressly racial harassment and threats of violence by the other children, who force her to run home every day. Yet she explains to her mother that “Doby doesn’t like the other children very much.”

Finally Sue is trapped by a group of white children and decides to fight back, hitting them with her fists. In the midst of this struggle, she realizes that Doby has disappeared, but she continues fighting until the white children flee. At first she searches for Doby but realizes that “he had gone for good. . . . She decided it probably had something to do with growing up.” A few minutes later several of the white children return and befriend her. When she arrives home late that afternoon, in their company, with scratched legs and a torn dress, she explains to her mother that “Doby’s gone. I can’t find him anywhere.”41

In 1988 Petry published a memoir revealing the origins of “Doby’s Gone.” When Petry was four, she and her older sister were walking home from their first day at school when a gang of older white boys began stoning and insulting them. The sisters fled to their house in tears, but their parents told them that they must return to school the next day and that they would be safe. Although dubious, the girls set out for home the following afternoon. When the gang of boys appeared and started to throw stones, “two of our uncles appeared, quite suddenly, and started knocking the attackers down—some of them they held and knocked their heads together, as they threatened them with sudden and violent death.”42 After that the sisters strolled home from school without harassment.

The modifications Petry made between the factual occurrence and the fictionalized rendition are instructional. Petry was born in Old Saybrook, Connecticut, but the fictional Sue is a new resident from upstate New York. Petry was only four, but Sue is six, the same age as Ann’s older sister. Ann accompanies her sister as Doby accompanies Sue. The sisters are attacked by older boys, but Sue is beaten by boys and girls who are the same age. The sisters are rescued by male uncles who meet violence with violence and terrorize the harassers, while Sue defends herself and ultimately earns the friendship of her antagonists. No doubt the most dramatic modification is the disappearance of the uncles from the fictionalized version. If the uncles had remained in the fictional version, there would have been no need for Sue’s dramatic change. This change occurs because, in defending herself, Sue frees herself of her dependence on a fantasy friend and learns how to cope with painful reality. In the context of the racist assault against Sue, this is a crucial step to her reclaiming her human agency in an unjust world of which she had been previously ignorant.

The other changes are significant as well, in that the story was published exactly six years after Petry moved from Old Saybrook to Harlem. It insinuates an allegory of the dramatic adjustment Petry had to make in her own sensibilities as she moved from her relatively protected small-town life to the shocking world of urban racism. No longer could her imagination continue to be nurtured by the fantasy and mystery reading of her youth, which was still evident in “Marie of the Cabin Club.” What was required was a new sense of reality as portrayed in “On Saturday the Siren Sounds at Noon.” Equally important was Petry’s growing consciousness through her activities in Negro Women, Inc., of the triple oppression of African American working women by race, gender, and class. Thus it was crucial, in her literary depiction of social forces as well as her characterization, to consciously turn her back on the customary portraits of African American women being trapped in religious ideology, passivity, or sexual promiscuity that had dominated American culture, including fiction by Black authors such as Richard Wright.43

The Street is set in 1944, a pivotal year in World War II. It was the year that the Allies liberated Italy and opened a second front with the invasion of Normandy. The Soviet Union drove the Germans out of Finland, Latvia, Estonia, and Lithuania, and the United States retook the Philippines. In the United States, Franklin Roosevelt won his fourth term, and the Communist Party dissolved into the Communist Political Association. In The Street, however, the only battles that occur are on the streets of Harlem, and the conflict is largely between African Americans and the environment in which they live, or between Black men and Black women. Prostitution and graft are rampant, and the only antiracist utopia extant is the white-owned Junto Bar and Grill, where African Americans with money are treated with respect.

When the World War II antifascist crusade is discussed in The Street, it is from a standpoint that challenges the Popular Front at its roots and even the more moderate versions of the Double V outlook. The most sustained reference to Nazism comes when Boots Smith, a former Pullman porter who leads the band at Junto’s, receives a draft notice and tells his boss that he needs to have it “fixed.” In answer to Junto’s questions about why he won’t fight the Nazis, Boots explains that “none of it means nothing. . . . They hate Germans, but they hate me worse. If that wasn’t so they wouldn’t have a separate army for black men.”

When Junto persists in asking what would induce Boots to fight, Boots responds, “Them white guys in the army are fighting for something. I ain’t got anything to fight for. . . . I got a hate for white folks here . . . so bad and so deep that I wouldn’t lift a finger to help ’em stop Germans or nobody else.” When Junto protests that “I don’t see—,” Boots interrupts him: “You never will because you ain’t never known what it’s like to live somewhere where you ain’t wanted and every white son-of-a-bitch that sees you goes out of his way to let you know you ain’t wanted. . . . Don’t talk to me about Germans. They’re only doing the same thing in Europe that’s been done in this country since the time it started.”44 The war in Europe, let alone the one in the Pacific, is seen through Boots’s eyes as immaterial to the survival of the Blacks of Harlem.

For Petry, the antifascist crusade could only have meaning to Boots and other African Americans if it also proposed action that addressed issues that immediately affected the lives of Harlemites. To be sure, the Popular Front policy promoted by the Communists at least rhetorically proposed to combine domestic antiracist struggles with antifascism, but its action program was constrained by the axiom that the defeat of the European fascists and Japan was the precondition for enhancing democracy in the United States. Publications such as the People’s Voice reflected a degree of overlap between radical expressions of the Popular Front and restrained expressions of Double V, although it seems that Petry’s characters, like those of John Oliver Killens in And Then We Heard the Thunder and Chester Himes in If He Hollers Let Him Go, could only be inspired by the most combative aspects of Double V—ones that proposed immediate struggles to uproot racism at home by means of militant mass action, work stoppages, and civil disobedience, regardless of whether they obstructed the Roosevelt government’s efforts in waging the war. To those beyond the constrictions of the Communist-led Popular Front, advocacy of rebellion in the streets was not excluded, or at the minimum, it was an understandable response to the insufferable state of affairs for most African Americans.

Boots, flush with the security of his new job at Junto’s, appears to have withdrawn from the battle of the streets as he also avoids the draft. Lutie Johnson, however, is still waging a war for daily survival; she shows no interest in the antifascist crusade, which appears principally in background conversation as remote. But Lutie’s war is waged under an obfuscating veil. Although she has partial insights into her situation, she cannot cut through the reified class and race oppression that dooms the efforts of herself and her son, Bub, to escape the fate of most African Americans. She knows that she is primarily in a war against the street, which symbolizes the poverty, the dirt, and the threat of violence surrounding the lives of the Harlem poor. She also wages a war against other African Americans—predominantly men who seek to exploit her for sexual gratification.

Perhaps more ominously, Petry sees an impending race war emerging from the tension in the Harlem community following incidents such as the stabbing of a poor Black man by a baker who claimed he was being robbed. The following day, as Lutie walks by the bakery, she sees “two cops right in front of the door, swinging nightsticks. She walked past, thinking that it was like a war that hadn’t got off to a start yet, though both sides were piling up ammunition and reserves and were now waiting for anything, any little excuse, a gesture, a word, a sudden loud noise—and pouf! It would start.”45 Lutie never verbalizes an attitude toward World War II similar to that expressed by Boots Smith. Instead, she is trapped in a wartime totalitarian-run house of her own, one that recalls the ghettoization of European Jews: “Streets like the one she lived on were no accident. They were the North’s lynch mobs, she thought bitterly; the method the big cities used to keep Negroes in their place. . . . From the time she was born, she had been hemmed into an ever-narrowing space, until now she was very nearly walled in and the wall had been built up brick by brick by eager white hands.”46 From the perspective of the Popular Front versus Double V debate, as presented in Killens’s And Then We Heard the Thunder, this is a house of racism that clearly cries out to be immediately torn down and built on new foundations—not one to be defended in the hope of gaining postwar rewards.

Petry’s literary strategy in The Street partially simulates the strategy of other radical urban novels—including James T. Farrell’s The Studs Lonigan Trilogy (1936) and Richard Wright’s Native Son (1940)—in its use of naturalist imagery, like the wind ripping down the street, to reify social oppression. While such motifs promoted critics to classify this type of literature as “naturalism,” the outlook of such Left writers cannot be reasoned out in terms of the passivity in relation to the power of environment or the denial of human agency that the term “naturalism” connotes. Ironically, the aim of Farrell, Wright, and Petry was to spur the reader to surmount the apprehension of social forces as the fixed forces of nature, which was how their fictional protagonists misunderstood their situations. In that these novelists were variously drawn to Marxism, they wished to move their audience to a clear critical consciousness that apprehended the class basis of institutionalized poverty and racism. This “dereified” understanding in turn would point the way toward the collective efforts needed for social transformation. But how does an author use the techniques of art to accomplish this end?

Farrell chose to confront the reader with the banality of Studs Lonigan’s musings and perceptions, while posing on the horizon an alternative perspective through the means of a minor character, Danny O’Neill, and intimations of a growing radical movement. Wright used a lengthy courtroom speech by his alter ego, Mr. Max, a humanitarian Jewish lawyer and Communist fellow traveler. Ann Petry, in her quest to develop characters shaped by yet beyond the determinations of social existence, fashioned a third, riskier way.

Lutie Johnson commences her war against the street—in effect, the domestic equivalent of fascism—with an inappropriately elitist philosophy. Her middle-class assessment of 116th Street in Harlem as a “jungle” filled with “the snakes, the wolves, the foxes, the bears that prowled and loped and crawled on their bellies” would ultimately segregate her from any possible community, setting the stage for her isolation and consequent downfall.47 Additionally, Lutie finds nothing in her understanding of African American culture to assist her efforts to resist. Unlike Petry’s own experience, the stories of Lutie’s Granny are simply “nonsense” to her.48 The Black church, a force for change in Harlem at the time, is perceived as meaningless by her. Adhering to an ideology of self-reliance inappropriate to her circumstances, Lutie thinks she understands the street; she believes that one can fight it by way of a personal resolution to earn money in a dignified manner and rise above others. Yet she ends up killing another victim of forces stronger than himself, Boots Smith, and as a result condemns her son to a destitute childhood without his mother.

The method that Petry used to avoid the pitfalls of reductive characterization and the interpolation of idealized solutions might be identified as one of subtraction. Subtraction occurs in the sense that a general view of potential social solutions—such as those found in the 1942 People’s Voice editorial—was familiar to Petry. These in all probability shaped her approach to many aspects of the novel but were deliberately excluded from dramatic representation either in the form of events or by articulation of her fictional protagonists. The Street’s characters are destined to proceed in the absence of such solutions. Negative factors are very much present, and some characters become increasingly cognizant of them; but Petry excludes dialogue or symbolic actions that point the way to a positive resolution of her characters’ situation.

Her strategic decision not to dramatize facile answers remains grounded in a social-realist strategy, quite unlike the modernist and postmodernist advocacy of an open-ended play of signifiers wherein the reader may construct his or her own contingent meanings. The distancing of social cause in Petry’s novel is used for the artistic purpose of accentuating her characters’ internal struggles. Thus the reader principally witnesses Lutie not as determined by particular societal agents but as psychologically ensnared by her unsuitable philosophy that was inspired by the writings of Benjamin Franklin. This leads to Lutie’s uncharitable, occasionally racist perceptions of her fellow Harlemites, as well as her reified, naturalist view of the street.

Consequently she acts in ways that show little understanding that the class and race domination of her fellow Harlemites requires a collective response. As in James T. Farrell’s work, one sees glimmers of ambient factors that could, under other circumstances, lead toward a dereified consciousness and eventual social amelioration. These include Lutie’s startling recognition that the women in the waiting room at the Children’s Shelter were bonded by poverty, not race, and her momentary sense of community and power as she emerges from the subway in Harlem after being in the white sections of New York.

The raw materials of The Street are substantially based on what Petry saw and learned during her activities as a People’s Voice reporter. In 1943 Petry joined Harlem’s Play School Association Project at Public School No. 10, working as a recreation specialist developing community programs “for parents and children in problem areas.”49 Petry could conceivably have been Lutie, if she had been suddenly deposited as an unemployed single mother in Harlem without the strong nurturing family and professional skills she had acquired in Connecticut and the political consciousness she had gained from her experiences at the People’s Voice.

Although its name, Junto, is the same as that of a business club associated with Benjamin Franklin, the interracial lounge in the novel derives certain of its features from the Savoy ballroom. The Savoy’s owner was white, but he remained in the background while a Black man managed the ballroom. Perhaps the character of Junto appropriates elements of Dutch Schultz (a pseudonym for Arthur Flegenheimer), who grew up in Jewish Harlem and later forced his way into a partnership with the Black gangsters who ran the numbers game.50 The political implications of the novel suggest that Petry had formulated an outlook on antiracist politics during World War II influenced by yet broader than the Communist-led Popular Front.

“HITLER’S UPRISINGS IN AMERICA”

Her politics are abundantly evident if one scrutinizes a story that Petry published a year later, one that is less beholden to the strategy of subtraction and comes closer to addressing the politics of social change. “In Darkness and Confusion” appeared in the third of Edwin Seaver’s annual literary anthologies, Cross-Section: A Collection of New American Writing (1944).51 The twenty-page story is a forceful literary portrait of the Harlem rebellion (customarily called the Harlem Riot) of 1943; it also presents poor African Americans in a light acutely different from Lutie Johnson’s conceptions of them. Most significant, perhaps, is that the political take on the rebellion in the story is categorically at odds with that of the Communist movement at the time of the rebellion, which occurred four years prior to the publication of the story.

The Detroit and Harlem riots and the so-called Zoot Suit Riot in Los Angeles about which Chester Himes wrote in 1943 were disconcerting jolts to the Popular Front strategy during World War II. The violence in Harlem, which had a distinctly anti-Semitic component—Jewish shopkeepers were central targets—was a clear disruption of the war effort, since work was halted and resources had to be diverted to quell the disorder and looting. Moreover, the episodes were major embarrassments to the effort of the United States to present itself as the beacon of freedom and democracy. In addition, it would be easy to conclude from these and similar urban revolts that the Blacks and Chicanos involved in them did not share the view that the only road to liberation was through the subordination of all other struggles to achieving victory over the Axis.

The urban rebellions created a dilemma for the Communist Party, which was fiercely committed to antiracism. It had a long and honorable history of defending oppressed people who had committed violent acts or committed crimes as a consequence of the deprivations and pressures of class society and bigotry. How could the Communists maintain their antiracist stance and simultaneously oppose any activities that might jeopardize war production? The Party’s solution was to take the position that all three “riots” were instigated by profascist agents and their domestic allies (fifth columnists); such elements were accused of manipulating the racially tense situations in all three cities to create “insurrections” against a pro-Allied government in a manner calculated to assist the fascist and Japanese war efforts. This enabled the Communists to denounce racism and appropriately link it to fascism, but at the cost of minimizing the horrific conditions of ghetto poverty and of depicting the African Americans and Mexican Americans who exploded in pent-up rage and frustration as the unwitting agents of Germany and Japan.

No evidence at that time (or later) came to light giving credibility to the Party’s explanation of the riots. Of course, there were racist and fascist-like groups in all urban centers. Detroit was home to Father Coughlin’s Christian Front and Gerald L. K. Smith’s America First Party, and there was at least one clash there in which Ku Klux Klansmen played the instigating role. Pro-Japanese propaganda circulated in a number of African American communities. Moreover, in New York, anti-Semitism had been present in Harlem long before the war, inflamed by African American distrust of Jewish shopkeepers and resentment of the “Bronx Slave Market” where Black women gathered each morning to make themselves available as domestics to a clientele that was heavily Jewish.

These facts notwithstanding, all available evidence indicates that the three riots were triggered by different instances of interracial conflict, although in each case the incidents became extravagantly distorted as accounts of them were spread by word of mouth. In Detroit and Harlem, the incidents ignited long-simmering rage and distrust in the Black community, not only about the persistence of racism and economic oppression, but about the mistreatment of Black soldiers in the segregated military.52

In “Fifth Column Diversion in Detroit,” a protracted report published in the Communist Party theoretical journal, The Communist, Max Weiss claimed that “the nation has been the shocked witness of . . . Axis-inspired riots in Mobile, Beaumont, Los Angeles, Chester, Newark—and their culmination in the insurrection in Detroit—which brought the full extent of these Hitler diversionary tactics to the attention of the nation.” Moreover, the fascist conspiracy had been successful: “The direct results achieved by the fifth-column forces responsible for these outrages can actually be measured in terms of the man-hours of war production lost—more than a million in Detroit, and hundreds of thousands in Beaumont, Mobile, and other places.” Further, Weiss claimed that this “Axis fifth-column plan to disrupt and divert the home front” was also evident in the strikes of the United Mine Workers.

Weiss held that anyone who insinuated that the Detroit and Los Angeles riots were “purely American” race riots similar to post–World War I riots in Chicago and East St. Louis was guilty of absolving “the Axis and its American fifth column from their direct and immediate responsibility.” Moreover, any attempt to suggest that the violence was caused by growing “tension” between whites and people of color would be tantamount to saying that the Nazi persecution of Jews was the outcome of tension between the two groups. To the contrary, he maintained that Negro-white unity in the United States had been clearly on the up-swing during the war.

What had occurred, according to Weiss, were “insurrections against the war effort, consciously and deliberately organized by Hitler’s fifth column in America, with the weakest link in the chain of our national unity—the integration of the Negro people into the war effort—selected as the sector of the home front on which to make a break-through.” Weiss conceded that in Detroit “90 per cent of the Negroes killed were killed by the police” and “85 per cent of those arrested by the police were Negroes.” However, this toll only confirmed that the “fifth column has, through one or another of its many agencies, penetrated quite extensively into the police forces in a number of cities.”53

Following the August riot in Harlem, the 14 September 1943 issue of the New Masses featured Earl Browder’s article “Hitler’s Uprisings in America.” The episodes in Detroit, Los Angeles, and Harlem are described as “Hitler at work on our own soil, dealing us blows heavier than those he has inflicted against us on the battlefield.” Detroit, according to Browder, was “the clearest and most outstanding example of Hitler’s invasion of America to date.” Browder was particularly rankled by the statements of those who “deny any Hitlerite origin or significance” to the events and who claim that “these disturbances are all of domestic manufacture, one hundred per cent American.” The “cold truth” was that the Los Angeles, Detroit, and Harlem explosions had occurred precisely “in the middle of 1943, on orders from Berlin, at a moment chosen by Hitler, for objects that benefit Hitler.”

Browder also took a strong rhetorical stand against the segregated military. He observed that the racist practice hindered the efficiency of the army, branded the United States with a moral stigma in the eyes of the world, and caused “the patriotic Negro population, ten per cent of the country, [to be] aroused to a high pitch of indignation by the treatment of its men in the armed forces.” Browder also took exception to the concept that “we ‘postpone’ the fight against anti-Negroism and anti-Semitism until the war had been won, because, forsooth, this fight might ‘interfere with the prosecution of the war!’” On the contrary, “Defeat and abolition of these doctrines of racial superiority, the complete removal of their influence from social and political relationships within the nation, are a necessary part of achieving victory in the war.”

What actions, then, did Browder propose for confronting anti-Black racism? His concluding point was that “anti-Negroism in all its manifestations of Jim Crow segregation, poll-tax laws, and all their consequences, must be rooted out of American social and political practice by laws, by energetic administration, and by public education.” Absent from his proposal were the usual endorsements of radical tactics of mass social action such as strikes, sit-ins, and any other activity that might be considered disruptive but could bring a more immediate redress. Moreover, Browder used the abstract but noble sentiments the Party shared with the Double V movement to provide cover for the unconscionable smear that the revolt in Harlem was created and manipulated by outside, Nazi agitators.54

In The Street there is not the least indication that fascist agents were manufacturing the potentially incendiary conditions so graphically depicted by Petry. The environment of domestic race and class oppression was an adequate justification for the eruptions. The triggering circumstances are foreshadowed. The only space relatively free of racism in the Harlem community is among gangsters, which insinuates that gangsters might have the capacity to gain yet more influence, even in the political sphere. Yet the main gangster in The Street, Junto, has fought his way up from the depths of the poverty-stricken sector of New York and is genuinely puzzled by Boots Smith’s negative attitude toward the antifascist crusade. Although Petry obviously intends the Black-on-Black violence to be a misdirected expression of legitimate rage, there is no suggestion that appropriate targets of Black rage should be fifth columnists or American fascists such as the Ku Klux Klan. Petry’s target is primarily the social, political, and economic system in the United States that fosters race, class, and gender oppression.

Even more compelling evidence of Petry’s outlook on the homegrown nature of wartime rage in Harlem can be found in her 1947 short story, “In Darkness and Confusion.” Her protagonist is named William Jones, who shares the same last name as the depraved and threatening building superintendent in The Street. But this Jones is the devoted husband of an enormously fat and very dark woman called Pink, and he is father to his son, Sam, and a niece, Annie May, who lives with them. Sam’s plans for college were dashed when he was drafted into the army and sent to Georgia for training. Annie May is a defiant eighteen-year-old who stays out half the night and cannot hold a job. Much of Jones’s reflections and conduct are devoted to protecting Pink. He is concerned about Sam, who has stopped sending the family letters; he worries about Annie May, who seems headed on an irresponsible and self-destructive course; and he is especially worried about Pink, whose obesity and hard life threaten to worsen her heart condition.

Jones is employed as a porter in a drugstore. After work he wanders over to a barbershop to get a haircut and participate in the latest discussion about the course of the war. Among the customers he spots a soldier on leave from Sam’s base and quickly drags out of him the shocking news that Sam is in an army prison. Sam was shot in the stomach by a military policeman for refusing to obey the Jim Crow law requiring him to ride in the back of a bus. Sam, in turn, shot the MP in the shoulder. He was sentenced to twenty years at hard labor.

Jones returns home desperate to keep the upsetting news from Pink. But he has a run-in with Annie May, who is exceedingly rude to him and announces her intention of moving out. When Pink returns from work at midnight, she takes Annie May’s side, and Jones is left to ruminate on the failures of his life. The next morning is Sunday, and Pink prepares to go to church all day by herself. After a few hours Jones goes to a bar to think more about Sam’s situation. The bar opens into a hotel lobby, and at this point Jones witnesses events roughly identical to those that scholars now believe set off the Harlem Riot in August 1943.55

In the lobby a white police officer is involved in a conflict with an inebriated Black woman, and an African American soldier intervenes. The tall soldier resembles Sam, and Jones watches in horror as the soldier wrests away the police-man’s nightstick and hits him on the chin. With a crowd gathering, the policeman reaches for his gun, and the soldier starts to run. A shot is heard, and the soldier drops to the ground; word starts to spread through the crowd that the soldier is dead. To Jones, “it was like having Sam killed before his eyes.”56

An ambulance arrives to take the soldier to the hospital, and the crowd, now in the hundreds, starts to follow the vehicle. Mounted white police officers fruitlessly try to disperse the throng. Jones joins the mob as his rage against Sam’s twenty-year sentence is transmuted into rage at the police. He also recalls that the hospital toward which he is marching was where he and Pink had been subjected to racist insults when their last child died there. He begins to take pleasure from the power of the throng and the fear visible on the faces of the white authorities: “He began to feel that this night was the first time he’d ever really been alive.”57

He then runs into Pink, who is carrying a large bottle of cream soda, amidst a group of women emerging from late church services. Jones abruptly blurts out the news of Sam’s twenty-year sentence and then tells her of the killing of the soldier in the bar—although he admits to himself that he does not definitely know if the soldier was killed. Jones’s only explanation of the shift from his protective attitude toward Pink is “She had to know sometime and this was the right place to tell her. In this semidarkness, in this confusion of noises.”58 Pink emits a high-pitched wail and heaves her soda bottle through the plate glass window of a furniture store. She then grabs a footstool and uses it to break the window of a dress shop.

As Pink, whose name seems to have revolutionary political connotations, continues her destructive spree, the mob follows suit, and Jones feels a great pride in his wife. Jones also begins thinking about how old he will be when Sam is finally released from prison, and this spurs him to accompany Pink as she leads the mob in attacking one white-owned store after another. When Jones spots Annie May destroying a naked white clothes dummy, he suddenly feels compassion for her: “She never had anything but badly paying jobs—working for young white women who probably despised her. . . . She didn’t want just the nigger end of things. . . . All along she’d been trying the only way she knew how to squeeze out of life a little something for herself.”59

Before Jones can connect with Annie May, he is swept to another intersection where the police are clubbing and arresting looters, and cars with loudspeakers are calling on the “good people of Harlem” to desist. Jones is revolted by the loudspeakers, as he repeats the phrase “of Harlem”: “We don’t belong anywhere, he thought.”60 In response to the appeals, he grabs a summer suit from a clothing store, then finds himself in a music store smashing all the records. By the time he finds Pink again, her rage against “the world that had taken her son” has reached a zenith. She rips the iron gate off a liquor store and, with eyes “evil and triumphant,” urges the mob “to drink up the white man’s liquor.”61

Yet Pink quickly finds that it is the iron gate (or the world) that had actually triumphed, for she starts to stumble as “the rage that had been in her was gone, leaving her completely exhausted.”62 Jones tries to lead her home; but she collapses along the way, and her heart gives out. In the final sorrowful paragraphs, Jones discovers that he has changed:

All his life, moments of despair and frustration had left him speechless—strangled by the words that rose in his throat. This time the words poured out.

He sent his voice raging into the darkness and the awful confusion of noises. “The sons of bitches,” he shouted. “The sons of bitches.”63

Petry’s view of the crisis of the Harlem Riot is unambiguous: The riot in Harlem grew out of homegrown racism, as expressed in the terrible social and economic circumstances that were exacerbated by wartime conditions. In particular, drafting Black men from the North into a segregated army and sending them to the Jim Crow South for training for mainly menial service jobs added insult to injury.

The rage in Harlem grows in the absence of a radical social movement in which Harlemites could gain access to the ideas and ideology that might afford hope and a political strategy. It is not surprising that rage experienced “in darkness and confusion” might transmute into looting and violence. It is indicative of the failure of the Harlem Left that the unidentified community leaders who emerged in cars with loudspeakers to pacify the crowd are met with contempt by Petry’s protagonist. To be sure, the perspective of the politically sophisticated Petry should not be confused with Jones’s perspective. Nevertheless, in crafting this plot Petry was fully aware that the leaders of the Communist Party in Harlem and others grouped around the People’s Voice (Adam Clayton Powell was out of town) had been central to the pacification efforts she depicts in the story.64

Petry’s political and literary evolution after The Street is marked by several abrupt developments. These are likely connected to her increasing disillusionment with the organized Left and her understandable desire for some self-protective cover, given the onset of Cold War–McCarthyite political repression. As The Street was receiving national attention, Petry boldly announced a plan to write a series of novels addressing various facets of African American life. She was asked by Ebony in April 1946 if she might soon write about Euro-Americans. Her reply was reported as follows: “She admits to being primarily interested in writing about Negro life though she will not say she will never write a book with a non-Negro theme.” She is then quoted: “‘For the moment . . . I am mainly concerned with Negro life.’”65

Yet only one year later she published her second novel, Country Place (1947), which focused on white characters in a rural setting with few African Americans. Taking into account the length of time it takes for editors to accept a novel, recommend revisions in the text, and move through the production process, it is hard to guess when this full-length work was written or how her decision to focus on white characters so quickly displaced her previously announced plans.

Country Place appears as if it were a partial retreat to Petry’s earlier pulp-fiction literary strategies. Although she would always describe it as a novel about a storm in a rural area, Country Place is actually about the consequences of wartime adultery and features a womanizer who sleeps with both a mother and her daughter.66 In 1971 Petry denied that she intentionally wrote the novel to extend her repertoire into new racial terrain. She explained that “I happened to have been in a small town in Connecticut during a hurricane—I decided to write about the violent, devastating storm and its effect on the town and the people who lived there.” She subsequently identified the town as Old Saybrook and the year of the storm as 1938; her explanation for the predominantly white characters is that the novel reflects the actual racial composition of the town.67 The text of the novel and her statements about it seem to contradict her statement a year earlier in the March 1946 Daily Worker that she regarded herself as an “emotional arouser” who aimed to write a series of books that will “move [the public] to action.”

At the moment Country Place was published, Petry moved with her husband to her birthplace of Old Saybrook; this time there were no interviews in which she might be asked to explain her rapid change of circumstances. She was then thirty-nine, and she resided in Old Saybrook until her death fifty years later. Although Petry episodically reviewed novels for New York newspapers in the late 1940s and early 1950s, most of her literary efforts were devoted to writing fiction for children and young adults. These include The Drugstore Cat (1949), Harriet Tubman, Conductor on the Underground Railroad (1955), Tituba of Salem Village (1964), and Legends of the Saints (1970). In 1958 she wrote a screenplay for Columbia Pictures (intended to be “That Hill Girl,” starring Kim Novak) and five short stories. Her political concerns are still evident in many of these stories. Moreover, her third and final novel, The Narrows (1953), which will be discussed in volume 3 of this series, would be a monumental work that reconfigured the issues of race, gender, and Cold War repression on a new and striking plane.

In later years, Petry claimed that she left the People’s Voice in mid-1944 because it was closing. However, the newspaper lasted until 1948. Among Petry’s personal papers is the notification of her dismissal in mid-1943 due to staff cutbacks made for financial reasons. After her departure, both her “Lighter Side” and “National Roundup” columns were briefly assumed by Marvel Cooke before they were dropped. Apparently Petry appealed her dismissal to the Newspaper Guild on the grounds that she had not been given proper advance notification. The dismissal did not alter her commitment to the People’s Committee.

Petry would later assert that she left New York City because she could not cope with her fame there; in particular, she did not like to “answer questions.”68 Perhaps coincidentally, the timing of her move back to Connecticut was congruent with the launch of the Cold War and the purging of left-wing staff members from the People’s Voice. By the mid-1940s, Adam Clayton Powell recognized how vulnerable he was to having the Communist label pinned on him. So in 1946 he fired Doxey Wilkinson and forced Max Yergan to resign from the People’s Voice. Marvel Cooke left in protest, and the paper filed for bankruptcy in 1947 and ceased publication the next year. Petry never said a word about any aspect of this period in her autobiographical writings or in interviews. Indeed, the author of a 1996 dissertation subtitled “The Short Fiction of Ann Petry” observed with justification that Petry, all the way up until her death, “has not been particularly forthcoming or cooperative concerning her career.”69 This reticence is clearly corroborated by Petry’s grumpy and brief responses to questions from various interviewers over the years.70

There is reason to distrust Petry’s terse answers to some questions. In an exchange that might have cast light on her role with the People’s Voice and the People’s Committee, and their relationship to her writing, Petry was asked by an interviewer, “I know that you worked as a reporter in Harlem for six years. Did this experience affect your writing in any way, perhaps both your style and subject matter?” Petry’s monosyllabic reply was “Doubtful.” There is evidence that something other than “doubtful” could have been said in response to the question. A compelling example can be found in a March 1946 interview in the Left-liberal newspaper PM, to which Petry occasionally contributed and whose printing presses were used to print the People’s Voice. Petry stated forthrightly that “the kinds of violence” she wrote about in The Street came directly from her work as a reporter. She specifically related how she covered the stabbing in the back of an African American youth by a white delicatessen owner. The same incident is introduced in The Street, but the delicatessen owner is a baker who stabbed a Black youth for taking a piece of bread, recalling the “crime” of Jean Valjean in Victor Hugo’s Les Miserables (1862).

Petry’s interviews in the 1970s and 1980s show that she was happy to provide the names of all her relatives, writing teachers, and authors whom she met, but long after the end of McCarthyism, not one of her fascinating People’s Voice comrades is recalled. Marvel Cooke, the Communist and People’s Voice managing editor subpoenaed by HUAC, nonetheless insisted that she and Petry were “very good friends” and that she had spent “many weekends” visiting with Petry. Cooke was also sure that Petry was well read in Marxism and that she considered herself to be “very friendly” to, although not a member of, the Communist Party.71 As for providing a literary interpretation, Petry’s interviews in 1946 reveal an eagerness to explain her fiction and its underlying purpose; after the 1950s, she resists interpretation of her work.