5

Disappearing Acts

HENRY ROTH’S LANDSCAPE OF GUILT

When recounting the fortunes of the Communist-led cultural movement during the antifascist crusade, one is tempted to explain the revolving door of personnel as a function of the Communist Party’s political mutations. The apostatic drama is heightened when famous writers depart the Party at critical turning points, sometimes with public fanfare. One thinks of James T. Farrell (1904–79) and John Dos Passos (1896–1970) breaking ranks during the Moscow Trials and the Spanish Civil War, Granville Hicks and Malcolm Cowley resigning from the Party and the League of American Writers in response to the Hitler-Stalin Pact; Richard Wright withdrawing from Party activity in revulsion because of its World War II policy subordinating African American protests to national unity; Ruth McKenney enduring public expulsion from the Party (as an ultra-Leftist) in the wake of the removal of Party general secretary Earl Browder (as a right-wing revisionist); and veteran Communist Howard Fast venting his anguish in The Naked God (1957) at the time of Nikita Khrushchev’s revelatory speech to the Twentieth Congress of the Communist Party of the Soviet Union.

Yet a focus on famous “breaks” with Communism tends to depreciate other salient factors in the forging of the Communist literary tradition. One factor is the ample number of writers whose departures from the tradition are not wholly explicable by political disillusionment at prominent conjunctures. Communist political beliefs do not always transcend other formidable facets of life. Overall, there is little evidence to substantiate the contentions of several pioneering books about the literary Left that writers were destroyed en masse by their Communist political commitments or that, after the early 1930s, only one-book authors and literary hacks were attracted to Communism. Such an assessment is essentially a reductionist conclusion to an abbreviated political critique.1 To be sure, turnover was continuous, and oppositional cultural movements such as the one led by Communists tended to attract more neophytes than established writers. But departures and unfulfilled professional lives often had their own explanations. Among the leading causes among rank-and-file members of the literary Left are traumas carried over from youth, inherited mental illness, physical ailments, premature death, lack of time and energy due to work obligations, expatriation, accusations of espionage, and diversions of interest. Some of these instances will be discussed here; others, in volume 3 of this series.

A pattern of quiet departures from the movement and the cessation of writing by promising writers began with the creation of the movement itself. The year 1934, however, has a peculiar prominence due to the spectacular disappearing acts of two young writers, aged twenty-five and twenty-eight. One, Henry Roth, authored what is now judged to be perhaps the most highly regarded novel of the pre–World War II Left, Call It Sleep; the other, Lauren Gilfillan, wrote one of the most widely read books in the early 1930s, I Went to Pit College. In early 1935, both writers signed the call for the First American Writers Congress on the cusp of the turn toward the Popular Front. After that, one vanished for three decades and the other for life. The failure of these two neophyte writers to follow up their initial successes can be blamed on neither Communism nor political commitment, but instead on the social and biological tragedies of humanity.

Call It Sleep was unquestionably drafted during Henry Roth’s accelerating political radicalization, although he drew on memories that had accrued during earlier decades. While attending City College of New York in 1924–28, Roth became sympathetic to the Left; his loyalties were not solely to the Communist Party, but he acutely judged the Soviet Union as “a new social order built on the proletariat.”2 He sensed such sentiments surfacing as a logical and organic outgrowth of the situation in which he and his contemporaries found themselves. One individual from City College he recalled was Morris U. Schappes. Like Schappes, many students were Jewish and the children of immigrants who worked in sweatshops. Characteristically, Roth’s initial sympathies for the Left were based on an abstract attraction to Marxism rather than readings of Marx and Lenin, which would come later. Moreover, the poverty he had known in his youth was no longer a pressing factor. By 1927 Roth was living with New York University English professor Eda Lou Walton (1898–1961), ten years his senior. When the Depression began two years later, the suffering of ordinary working people seemed to him like a spectacle with himself as an observer.

Wearing an English jacket purchased for him by Walton, Roth walked the streets and watched men standing in soup-kitchen lines and living in Hoovervilles. As he hovered on the fringes of the discussions in Walton’s literary salon, Roth observed the shift in the conversation of the salon’s intellectuals from quasi-mystical ruminations about the poetry of William Blake to impassioned arguments about the relation of the artist to Marxism and “the Revolution.” Between

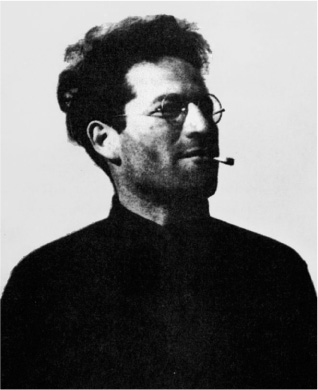

HENRY ROTH joined the Communist movement in 1933 and remained sympathetic for the next three decades. (Photograph by John Mills IV; courtesy of John Mills V)

1930 and 1932, Walton’s soirees began to attract adherents of the Communist Party.

Hitherto the salon had been primarily attended by poets such as Leonie Adams (1899–1988) and Lynn Riggs (1899–1954); friends such as Ann Singleton and Hal White; the critic William Troy (1903–61); and the anthropologist Margaret Mead (1901–78). Among the new participants were the pro-Communist poets Horace Gregory (1898–1982) and Genevieve Taggard (1894–1948). Soon Richard and Louise Bransten, wealthy Jewish Communist activists from California, joined the salon. Richard Bransten, an aspiring but unsuccessful novelist, was for Roth an imposing figure; in contrast to the memory of Bransten held by others, Roth recalled him as handsomely built, articulate, and able to summarize the political situation in a personal and comprehensible way.3 Roth’s gravitation toward Communist Party commitment accelerated as Call It Sleep poured out onto paper.

In the summer of 1932, Hal White helped Walton locate a cottage in Maine where Roth was able to complete the major portion of the novel. When Roth returned to New York in the fall, he struck up an acquaintance with a carpenter who had been called to his building to do some work for Mary Fox, a Leftist neighbor affiliated with Theater Union. The carpenter’s name was Frank Green, and Walton also subsequently employed him. Green was a Communist Party militant with a distinctive Irish accent who had traveled the world as a ship’s carpenter. Roth was enchanted with Green, and soon they became intimate friends.

Unsuspecting of Roth’s literary activities, Green brought him to a meeting of a waterfront unit of the Communist Party that had been organized to influence the International Longshoreman’s Association. At the meeting, Communist Party leader Charles Krumbein gave a speech and asked all visitors to join the Party. Green had brought another guest who declined, but Roth agreed to join and was soon writing leaflets and attending classes on Marxism. Walton was horrified by the news of her protégé’s Party membership; Roth recalled that she stayed up all night mourning what she feared would be the loss of his creativity. Walton’s concerns were magnified when the 1934 West Coast longshoremen’s strike broke out. The Party supported longshoremen’s leader Harry Bridges and began to distribute literature on his behalf. Roth was caught passing out leaflets under a viaduct by goons working for Bridges’s rival, and they beat him badly.

Roth’s decision to join a proletarian unit of the Party, rather than a unit of other writers, was symptomatic of his tormented psychological makeup. While others saw brilliance in his novel and in his conversation, he mysteriously suffered from low self-esteem and a strong sense of guilt prior to making his Communist Party commitment. He knew he had an ability to produce narrative, which he had demonstrated in a student essay he had published at City College in 1925.4

EDA LOU WALTON was a New York University professor who lived with and supported novelist Henry Roth during the 1930s. She became pro-Communist in the latter part of the decade. (From the Belitt Collection in the Howard Gotlieb Archival Research Center at Boston University)

Yet he nonetheless felt incapable of grasping abstract theories and following through on their implications, whether Marxian or Freudian. He also felt incompetent to handle office work and was therefore drawn to manual jobs, although Walton supported him for most of the 1930s. For reasons he could not explain, Roth was dependent on older and stronger individuals to care for him; his mother had, in fact, accepted his relationship with Walton precisely because she knew that he was being well fed, clothed, and housed.

Roth remained an active Party member while he finished Call It Sleep in 1933. In 1934, with the help of David Mandel, a labor attorney and friend of Walton’s who was part-owner of Ballou Publishers, the novel was published. Although the New Masses issued a short, unfavorable notice, the Daily Worker immediately hailed it as a masterpiece, and the New Masses judgment was buried under powerful letters to the editors hailing the novel.5 Despite this reception, Roth minimized his contact with Party intellectuals, aside from an occasional discussion with Samuel Sillen. When Green went back to sea as a ship’s carpenter, Roth transferred his need for a political mentor to a German American Communist who used the Party name Bill Clay.6 Clay, who had worked baking cookies for the Nabisco Company, had lost a hand in an industrial accident and was also tormented by an unfaithful wife.

Roth’s semiautobiographical Call It Sleep seemed to demand a sequel as the logical next step in the author’s literary development. But Roth’s fascination with Clay convinced him that he must instead write a novel based on Clay’s life. Although scholars have speculated that pressure from the Communist Party caused Roth to change the subject of his projected novel, Roth contended that the primary influence of the Party on him was to broaden his horizons beyond New York City.7 Roth’s view of Clay as an exciting character on which to base a new novel was not the only reason why he could not plunge ahead with a sequel to Call It Sleep. More likely he was paralyzed because he found it impossible to move the autobiographical character David Schearl to the next level. To re-create his own experiences, he would have had to depict David in incestuous relations with his sister and cousin. Instead, in Call It Sleep Roth had not mentioned his sister and had shifted sexual tension to David’s Oedipal complex in relation to an imaginary mother based on Eda Lou Walton.8

Sixty years later, when Roth finally wrote and published sequels to Call It Sleep, he revisited his early years. This time he included frequent episodes of incest between the autobiographical character, now named Ira, and his sister and his cousin. But Henry Roth in 1934 could not confront his youthful violation of sexual taboos, in fiction or personally. He created a persona free of the predispositions and temptations that would lead to sibling incest. His novel’s title, Call It Sleep, connotes the world of the unconscious to which he hoped to consign the guilt that haunted him, with unanticipated punishing consequences for his literary career.

During the mid-1930s, Roth was vexed by the double guilt over his sexual transgression and his situation of unearned privilege by virtue of Walton’s financial support. Joining the Party, under the tutelage of older male mentors, Green and Clay, was a means not only of assuaging guilt but also of defying Walton, his mentor-protector, and making a belated transition from adolescence to manhood. His relationship with Walton was emotionally convoluted; she continued to have affairs with other men and to tell Roth about them. One of these was with David Mandel, whom she later married. Breaking with Walton seemed to be the logical next step, as a rupture with her held the promise of sexual well-being.

Throughout the time Roth labored over his unfinished manuscript about a German American worker, he was engulfed alternately by sexual reveries and self-loathing that he had hoped his Party commitment would purge from his consciousness. In his torment he felt that he alone suffered from such conflicts. The more he struggled to escape his distressed psyche by immersing himself in the “impersonal” class struggle, the more he began to feel that his mental state was afflicted by “aberrations in desire and sexuality and sexual fantasy.”9 To him, the effort to commit himself to an ideology functioned as a kind of corrective sexual puritanism; it was also a response to his mother, who held socialist ideas without having any concrete political perspective. But the contradiction was wrenching; he was emotionally caught up in sexual fantasy and uncontrollable desire while intellectually pledged to the revolutionary cause. For a while he succumbed to the former and dropped his Party membership, becoming a fellow traveler. It was in that capacity that he agreed to Richard Bransten’s request to submit a statement of support for the Moscow Purge Trials—a thoroughly apolitical statement that appeared in the 2 March 1937 New Masses, in which his denunciation of Trotsky’s “monstrous ego” was more likely a self-criticism.10

When Roth attended the Yaddo artists’ colony in 1938, he met not only the writers James T. Farrell and Kenneth Fearing (1902–61) but also a radical composer, Muriel Parker. He then returned from Yaddo to find that Walton had become a Communist and that David Mandel, originally hostile to the Party, was a fellow traveler. At that point Roth informed Walton that he was involved with Parker and that their relationship was ended. Still under the influence of Clay, however, he decided that he might finalize his break from Walton by living on his own for a time. The plan was for the two men to travel to the West Coast for five or six months. En route they had a mission to carry out: Clay had been born in Ohio under such murky circumstances that he was unaware of his birth date. In 1938 Roth accompanied Clay to city hall in Cincinnati to discover the truth. Clay was appalled to learn that he was fifty years old. The two friends continued their westward journey. Roth and Clay had conflicts while in California, but Roth returned to New York feeling stronger and more independent and finally free of his need for Walton.

At that time war was looming. Shortly after he married Muriel Parker, Roth rejoined the Communist Party, and his new wife joined as well. With millions of men being drafted, Henry trained as a tool-and-die maker and became active in the United Electrical and Machine Workers Union. Following the war he and Muriel decided that they did not want to raise their two children in New York City and moved to Boston, where Henry worked at making gauges and tools at the Keystone Company and attempted to carry out Party work. But they found a housing shortage in Boston and were unable to afford a comfortable apartment. They read about available cheap housing in Maine, and Henry moved his family into an old house on a 100-acre farm. Initially Henry remained in Boston alone, continuing his Party work, but he found himself unable to recruit a single worker. Muriel became the chief breadwinner, and Henry moved to Maine to raise geese and ducks while in 1949–50 also working at a mental institution.

Henry Roth continued to receive Party literature, and Party members visited his home to discuss the political situation. But he became increasingly suspicious that these visitors were really FBI agents. When he noticed that a car was following his, he canceled his subscription to the Daily Worker. In 1951 his confidence in the Soviet Union was badly shaken by the “Doctors’ Plot” (Stalin’s paranoid accusation that a group of Jewish doctors were engaged in an attempt to assassinate Soviet leaders). His sympathy for the Party was now accompanied by a degree of mistrust. His adherence was further eroded by the 1956 Khrushchev revelations, although his membership by then had lapsed, and he paid little attention to the resulting internal Party struggle. When the FBI came to his house to question him, partly out of a concern that the breed of ducks he raised was called “Muscovite,” he told them, “If you want to know the closest thing for which I stand, I’m a Titoist.”11 With his literary aspirations long banished, he devoted himself to calculus problems for the next four or five years instead of reflecting on his personal and political past.

Until 1967 Roth still regarded himself as a Marxist and believed that the example of the Soviet Union as a model for socialism took precedence over all other concerns. Even when the USSR invaded Hungary in 1956, he thought that Soviet leaders were justified in halting what he perceived as a capitalist restoration there. When the Cuban Revolution occurred in 1959, he was wholly on the side of Fidel Castro. But at news of the 1967 war in the Middle East, he experienced a certain reversal. His training in the Party’s version of Marxism told him that the Arab forces were the more “progressive,” but he was terrified that several million Jews might be slaughtered. He had felt this way before, during World War II—as if his own life was at stake when the Red Army went into battle against Hitler—and again in 1962, as the Cuban revolutionaries faced down President John F. Kennedy.

This time, perhaps as a much-delayed aftershock of the Holocaust, the feelings of strength and power he derived from identifying with the victorious Israeli state were far more intense. Following the emergence of his new sense of ethnic belonging, Roth struggled to reestablish his identity as a writer, with occasional stories and interviews. After Muriel’s death in 1990, what remained of his writer’s block dissolved, and a new version of his childhood began to appear in a sequence of novels he wrote covering his adolescence and young manhood. Roth died just as the novels were coming off the press, but he had become something of a literary legend during the last three decades of his life. Although he was not exactly a literary phoenix rising from the ashes, his creative powers had been sufficiently restored to allow him to craft several new semiautobiographical novels. No such opportunity came to his female counterpart.

THE ORDEAL OF LAUREN GILFILLAN

Early in the summer of 1930, a twenty-one-year-old Smith College junior disrobed before an eminent physician in Kalamazoo, Michigan. The student’s worried mother had brought her home from Northampton, Massachusetts, where she had been hospitalized in a “highly nervous state” following repeated episodes of unconventional behavior.12 The student was Harriet Woodbridge Gilfillan (1909–78), and such episodes were not exceptional. Since age eight, when she had run away from home in quest of adventure, Harriet had exhibited high spirits and a rebellious temperament.

At age fourteen, Harriet displayed a precocious literary talent—producing diaries, poems, and letters—as well as an equally precocious preoccupation with sex. Harriet and her friends circulated “hot” books, one of which, The Plastic Age (1924), was about the dissipated life of a male college student; they disguised it inside the cover of Raphael Sabatini’s swashbuckling adventure novel The Sea Hawk (London, 1915; New York, 1924). In her early teen years, Harriet continued to disappear from home and frequently kept the company of homeless people whom, like everyone else, she affectionately called “bums.” She shocked her community by smoking in public, and she dreamed of having a Bohemian life. After graduating from Smith College, she planned to make a beeline for Greenwich

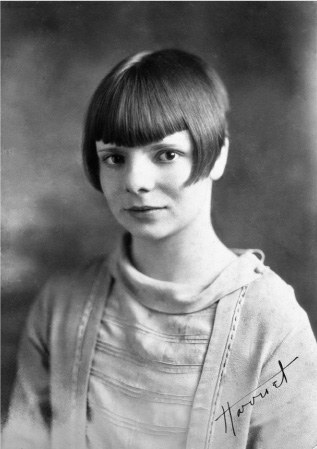

LAUREN GILFILLAN was a best-selling radical author of the early 1930s who disappeared from literary history. (Courtesy of Henry Gilfillan)

Village, where she would live in an artist’s garret and forge a career as a successful writer.

At age twenty-one, Harriet’s plans seemed threatened by incidents and episodes judged erratic by her family, friends, and teachers. The Kalamazoo doctor completed his examination, consulted with his colleagues, and presented Caroline Gilfillan, Harriet’s mother, his diagnosis of a psychological complex based on biological abnormalities of a sexual nature. Caroline quickly conveyed the diagnosis in a letter to Harriet’s Aunt Emily:

Her genital organs are undeveloped.

The uterus is infantile and she is so small that the doctors say she can never . . . deliver a child without a caesarian operation. . . . The doctors agreed that lack of development in the genital organs has its effects upon her mental make-up and that she will probably never be very stable. They say that her mentality is high and she may do splendidly in some congenial work—[but] she seems to live in a perpetual state of adolescence.13

Four years later, this perpetual adolescent who never grew taller than four feet, eight inches, was propelled to national fame when she published, under her new name, Lauren Gilfillan, the sensational best seller I Went to Pit College with the imprint of the Viking Press.

The book ostensibly was a nonfiction narrative in which a college graduate travels to the scene of the Great Coal Strike of 1931 in the coal town of Avella, Pennsylvania, thirty miles from Pittsburgh. “Pit College” is the ironic term that local miners use to refer to the mines, an allusion to the University of Pittsburgh, called Pitt for short, where the children of the wealthy went to college at that time. The protagonist, Laurie, disguises herself as a child, a boy, and a male coal miner, to gather information for a book during five weeks lived at a high-pitched intensity. The Pit College adventure includes hunger, violence, birth, death, romance, jealousy, and a sensational political trial—all the elements of a romantic or melodramatic novel. I Went to Pit College, however, was marketed as a mix of autobiography and reportage. Indeed, the very busy cover of the first edition features on the spine a photograph of the author in cap and gown at her graduation from Smith College; on the front jacket of the book are seven documentary pictures, one showing the author dressed in miner’s overalls beside a real miner and the others depicting various scenes of demonstrations, military occupation, shacks, and so on.

Selected as the Literary Guild Book for March 1934, I Went to Pit College was guaranteed an initial sale of 50,000 copies. But that scarcely accounts for the national sensation it created. There were more than seventy-five reviews; most were wildly enthusiastic, and some appeared on the front page of book review sections. Across the country there were announcements of meetings at public libraries and of small-town literary clubs where discussions of I Went to Pit College were to be held, usually preceded by a presentation on the book by a local woman. Gilfillan was the subject of dozens of news articles in which a standard biography recounted her upbringing in a family of social workers who lived in the Washington, D.C., slums at the time of her birth; the family’s subsequent move to the Midwest and Kalamazoo; Gilfillan’s dismay at finding herself unemployable after graduation from Smith College in the depths of the Depression; and finally, her acceptance of the “dare” of a publisher, George Palmer Putnam (husband of the aviator Amelia Earhart), to relocate to a coal mining town in order to immerse herself in an “experience” that would become the basis for a successful first book.14

Invariably as well, the authors of these interviews—usually male—would dwell on Gilfillan’s gender and physique to emphasize the contrast between her apparent female frailty and the horrors allegedly experienced by this “small Irish girl from Smith College” on her journey from middle-class security to the heart of darkness amidst western Pennsylvania’s coalfields. Typical was the amazement expressed by the leading critic Burton Rascoe in the March 1934 issue of Esquire: “A very sprite of a girl, so tiny, so doll-like and so helpless-looking that the almost uncontrollable masculine impulse is to pick her up and stuff her into an overcoat pocket, has written a book displaying terrifying courage.” The national acclaim accorded the book was well-summarized by the Raleigh, North Carolina, News and Observer. An article titled “Life in Mining Town Portrayed” referred to I Went to Pit College as the “book that has taken the country by storm” and went on to assert, “With one accord the book critics of the metropolis of New York have welcomed this volume as a harbinger of a new era in literature. A new star has swept into the literary firmament.”15

This new star, however, was to some extent an invention of the media, an invention required by the national imagination. The personality depicted in the papers facilitated the mediation between the America of the urban and the smalltown, book-reading public and the sudden, rather brutal emergence of an underclass that was forcing its way into the pages of literature and accordingly to the center of mass culture. The other America revealed in Gilfillan’s book, among many additional books in the 1930s, was largely peopled by the horrifically impoverished and exploited, most of whom were of Southern and Eastern European and African American ethnicities.

OF GENDERS AND GENRES

The naive, Girl Scout–like “Smithie” of the newspapers bore little resemblance to the real Gilfillan, as her life can be reconstructed or even as she engagingly appears in her own narrative. I Went to Pit College is a book that the scholar Paula Rabinowitz so aptly characterized in 1991 as “probably the most thoroughly self-reflexive piece of proletarian writing to emerge from the 1930s.”16 The headlines of the reviews from across the nation invariably emphasize an encounter between innocent, middle-class female vulnerability and the brutal “raw life” of the proletariat. Gilfillan seems to stand for the known and familiar, an extension of the reader’s sensibility, while the miners are both the other and the frightening reality. “College Girl in the Pennsylvania Mines” read the headline on the front page of the New York Herald Tribune books section, accompanied by a full-page color painting of a ramshackle Pittsburgh mine with two bent-backed workers walking in front of it. Other headlines include “College Girl among Striking Miners,” “Girl Reporter in Coal Country,” “Girl’s Story of Mine Town Is Grim but Fascinating,” “A Girl Writes of Miners,” “Girl in Mining Town,” “Smith Girl Observes Life among Poor Miners,” and “A College Girl Paints Life of Coal Pit Folk.”17 The Communist Daily Worker headline was a bit less dramatic, but the contrast of gender and class was still evident: “A College Girl Writes about Western Pennsylvania Miners.”18 A typical variation of such headlines would be “Degree in Raw Life Was Hers.” And to emphasize the corrosive effect of attending proletarian Pit College after the well-to-do and all-female Smith College, the issue of Time magazine for 5 March 1934 ran a photograph of Gilfillan looking quite prim and proper, while underneath the photograph a caption read, “Her make-up wore off.”19

The problem of describing the narrative’s relation to reality was as vexing for critics as articulating the exact genre of the narrative. Among the most tortured remarks were those of midwestern writer Zona Gale that appeared on the front page of the Herald Tribune books section: “In the accepted library classification of ‘fiction’ and ‘non-fiction’ . . . this book belongs to non-fiction, for it is a straight record of fact. But it is as absorbing as the best in fiction, and it is out of the stuff of which fiction is made.” At the same time, however, Gale apparently saw Pit College as some kind of photographic fiction. She concludes, “There is no brief, no thesis, no accusation. It accuses no more than the picture of typhoid fever. . . . It is today’s fiction—the new fiction that is about something vital concerning a group of today. Such fiction, being truth, is as strange and as terrible as truth always is. The book is fiction as Les Miserables is fiction—not because it tries to be, but because it cannot help it.”20

Such riddles became commonplace as various reviewers tried to reconcile their belief that the events depicted must be true with their sense that they were reading a novel. William Soslon declared in the 2 March 1934 New York American that the book has “the feeling of true reporting.” The New York Sun of the same date proclaimed it “good Reporting. . . . It is a superb piece of reporting.” And yet, “It reads like a novel.” Time magazine agreed that it “reads like a first-rate novel.” Herschel Brickell, in his column “Our Table” in the New York Post, explained that “it becomes more of a novel than many books that are classified as novels” but it is also “a fine and valuable social document.” “Social reporting after Survey Graphic’s heart,” stated the Survey Graphic of Concord, New Hampshire. The Nation simply characterized it as “a document of the plight of one group of workers.” “Essentially honest reporting” was the view of the “Books on Parade” section of the New York East Side Home News.21

Burton Rascoe went much further, proclaiming it “one of the great masterpieces of reporting.” Yet, the Yonkers New York Record insisted that “what results is an almost unbelievable account of her experiences.” Several other responses challenged the veracity of the text. Communists in the Daily Worker and the New Masses, although praising some aspects of the book, insisted that the portraits of Communist activists and the descriptions of YCL meetings were total fabrications. A minister who had worked in Avella insisted that the descriptions of the insensitivity of the church were slanderously false.22

Fifty years later an enterprising journalist for a western Pennsylvania newspaper went to Avella to interview participants in the Great Coal Strike. When the subject of Gilfillan’s book came up, those interviewed universally condemned it as fiction. They claimed that Gilfillan had dramatically exaggerated the degree of poverty, hunger, and ignorance of the population—the very issues that had so captivated the reading public.23

As might be expected, the Communist press took the most searching approach. After all, the book was about “their class”—the industrial working class moved into action by Depression conditions. Moreover, the Gilfillan phenomenon—the middle-class artist seeking to represent the proletarian other—was then a central issue of debate within the Party-led John Reed Clubs. In the May 1934 New Masses, there was a review by Party member Helen Kay. This was a pseudonym for children’s author Helen Goldfrank, who would later be revealed as a central character, Shirley, in Gilfillan’s book. Kay stated, “Many of the chapters lose out by the author’s efforts at fiction—which, if given in pure truth, would have added much to her work.” Gilfillan’s account of a Communist meeting, according to Kay, was typical of her fantastic fictionalizing. While acknowledging that other scenes, such as those of workers’ daily lives, comprised “a fine piece of reporting,” Kay nonetheless regarded I Went to Pit College as a “respectable college girl’s adventure among the savages.”24

Gilfillan posed an enigma for the Left. Clearly, she was sympathetic to the Communists’ aims, but she was also satirically critical of the Party members she depicted. She was especially amused by what she saw as their inappropriate tactics and their illusions about workers being motivated by a higher class-consciousness rather than pragmatic economic self-interest. Thus, it was nothing less than sensational when Gilfillan herself appeared at the John Reed Club meeting on 16 April 1934 to speak on the topic “The Ideology, Political and Literary, behind My Book.” What radicals called the bourgeois press, which covered the event, reported that Gilfillan admitted at the outset that she had had to look up the meaning of the word “ideology” in the dictionary before coming to the meeting. But all accounts—in the Communist as well as the mainstream press—agreed that she held her own in spite of a tumultuous situation that might have been any other author’s worst nightmare.25

According to a long description of the event in the Daily Worker by Nathan Adler, later an eminent clinical psychologist in the Bay Area, the floor was immediately taken by the New Masses reviewer Helen Kay. Kay revealed that it was she who had been portrayed in I Went to Pit College as the exotically beautiful Jewish “villainess” Shirley. In the Daily Worker, the amazed Adler depicted Kay’s intervention as that of “a character [who] was walking out of the pages of [Gilfillan’s] book to challenge the author, her ‘creator.’”26 In the book Shirley, the Communist Party organizer who is to some extent motivated by her jealousy over the transfer of the affections of Johnny Cersil, a young worker aspiring to be a writer, from herself to Laurie, persecutes Laurie as a possible ruling-class spy. In a memorable scene, Shirley delivers a powerful tirade against “art for art’s sake”—to which the awestruck and apparently worshipful Laurie can only reply, “Shirley, you’re beautiful!”27

Next spoke Pat Touey, a leader of the National Miners Union, who said that he had come to the event with “blood in his eye,” prepared to take revenge on the author—“but didn’t have the heart, after he saw this honest and disarmingly charming slip of a girl.”28 The most extensive remarks appeared in Partisan Review, then an official organ of the John Reed Club. The reviewer was Ben Field, a pseudonym for Moe Bragin (1901–86), at that time a short-story writer and later a quite prolific novelist. Field complained that Gilfillan’s work was corrupted by her insistence on remaining an outsider to the proletarian movement and that she could only shed her college miseducation and “imagery” of “middle class consciousness” by using Marxist analytical instruments and participating in the struggle.29 The Daily Worker reporter lionized Field as an example of a writer from the middle class who had given himself totally to the workers’ cause: “Field has come to us from her [i.e., Gilfillan’s] world and he has come to us simply, giving all of himself. He is earnest and humble. He knows and spoke honestly of the middle class artist grappling to destroy his old self so that he may approach the revolution.”30

Gilfillan defended her work, as reported in the Daily Worker, by saying that although she was struggling hard to make herself into a “revolutionary artist,” she found that “Communists sometimes showed too much fervor and not enough tact or appreciation for the psychological problems the individual was faced with.” She listened but did not capitulate to the onslaught of John Reed Club members, one of whom argued that “the writer with a middle class background dissects himself, all activity paralyzed; he retches painfully, tearing up clots of his innermost self; in the end he drowns in his own foul vomit.” Gilfillan retorted that the Communist “technique was bad. She said we wanted to knock her down and drag her home. She would come in her own way.”31

Gilfillan had been in dialogue with Communist Party members at least since the summer of 1931. In 1932 she cast her vote for Communist presidential candidate William Z. Foster. But she had consistently held her ground against the prevailing John Reed Club notion of writers transforming themselves into proletarian cultural soldiers in the Revolution. However, her insistence on retaining the “right” to her own personality was not so much due to her middle-class origins or Smith College education as the Communists and others thought it was. Despite her intense love for her family and a genuine adulation of her working professional mother, Gilfillan had long sought a release from middle-class conventionality. Her experiences at Smith College seem to have played a role only as a counterexample to a real education, which she identified with her work experience. It was Gilfillan’s radical, proletarian, and Bohemian identity—one that she had worked so hard to construct—that she was unwilling to simply “destroy.” It was by writing I Went to Pit College that she had finally and most fully given birth to her new identity, which was signaled by her abandoning the name Harriet, which she hated, for Lauren, which she thought was more colorful and less feminine.

THE WOUND AND THE BOW

The writer who went to Pit College was not at all a girl who clung to middle-class respectability or feared dirt, poverty, powerful emotions, and raw life. By and large, the middle-class values and ties demonstrated by the protagonist Laurie in the novel reflected Gilfillan’s self-satirization as remnants of a Harriet who had not yet been fully purged. The author who wrote the book was neither Harriet nor Laurie but Lauren, which was the name she called herself and wanted others to call her. Lauren was the antibourgeois Bohemian who readily took to the road with bums without a penny in her pocket and who sought out the roughest and wildest neighborhoods in which to live, furnishing her room with odds and ends that she borrowed, picked up on the street, or stole. Lauren was scarcely a repressed, middle-class puritan. She led a fast-paced and varied sexual life, sometimes with three dates a day. From the time she was a teenager her engaging personality attracted so many ardent male admirers that she could not help but break hearts, including that of “Johnny” in Avella.

In such a context, Gilfillan’s radicalism, although not essentially ideological, was strong and present as a natural expression of personal and cultural rebellion. After her stay in Avella, Gilfillan befriended the Left journalists Harvey O’Conner (1897–1987) and Jessie Lloyd (1904–88) in Pittsburgh. She was attracted to the idea of accompanying Lloyd to Kentucky to cover the murder trials that had grown out of the labor struggles there.32 Later Gilfillan lived at the Michigan home of the Federated Press editor Carl Haessler (1888–1972). She was fascinated by this “millionaire Communist” whose troupe of visitors had freshly returned from the USSR.

In the year between her departure in the fall of 1931 from Avella and her writing of I Went to Pit College in the winter of 1933, Gilfillan lived in both the African American community and Bohemia of Chicago, where she knew Ben Ray Reitman (1897–1942), the famed whorehouse doctor and lover of Emma Goldman. In correspondence with friends, and with George Palmer Putnam, the editor who had dared her to write I Went to Pit College and who acted as her literary agent in selling several excerpts from it, she frequently told them that she might join the Communist Party. Yet she also reported hilarious episodes where both she and the Communists trying to recruit her looked downright silly. Then suddenly in the midst of the debate about Party commitment that had surrounded her appearance at the John Reed Club, Gilfillan announced (at the beginning of that meeting) that she had recently married a Communist—the Hungarian-born anti-fascist militant Andrés Kersetz. The two were already deep into studying Lenin and about to depart for the Soviet Union.33

A year later, however, they quietly divorced. Gilfillan’s last publication, “Why Women Really Might as Well Be Communists as Not, or Machines in the Age of Love,” an essay that appeared in the dissident Marxist journal Modern Monthly, had been published in February 1935. By midsummer Gilfillan had vanished completely from public view. I Went to Pit College continued to sell steadily through the 1930s, going into its sixth printing in 1938. It was one of 200 best sellers chosen for the library of the White House, and in 1936 it was declared one of 700 books necessary for a home library.34

Gilfillan’s effort to tell what it was like to attend Pit College seems trapped between her need to respond to the Depression conditions by creating a character who behaved like many male role models in literature and the socially constructed female ideal that readers and reviewers attached to a female author and protagonist. The male role model character was, of course, the prevailing vehicle for a writer in quest of exciting material for a popular book; male experiences were normally acquired by fighting in a war, hitting the road, or seeking some other adventures. As the class struggle merged with antifascist sentiments after 1933, such a masculinist view of “real experience” was behind George Putnam’s dare to Gilfillan to move to the strike venue to gain material for a book. Indeed, Putnam had dared his son, David, to go to Antarctica to acquire material for a book, which he had done.35

On the other hand, when she was among the working-class community in Avella, and again as she faced the critics who reviewed her book and publicized her story, Gilfillan was placed in the conventional idealized role of a middle-class young woman. Harriet’s efforts to become Lauren were mostly misunderstood or not recognized. Nevertheless, the female protagonist of Pit College persists in trying to become Lauren. She smokes in public to the dismay of the Communists. She goes freely where she wants and speaks without restraint, to the astonishment of most of the men of the town who know only married or “bad” women. She cross-dresses without thinking twice. Then, after toying with her ardent lover Johnny, she goes absolutely gaga over the exotic Shirley. All of this is largely unremarked in reviews or in biographical sketches.

Like many women’s autobiographies, I Went to Pit College aims to make the invisible visible. Yet the emotional terrain the heroine treads is subordinated to the disclosure of the portrait of the reality of class oppression of the “other America” comprised of Slovaks, Poles, Germans, Italians, Lithuanians, Greeks, Russians, Bulgarians, and African Americans. While there are other women in I Went to Pit College and there are a union, political parties, and families who want to take her in, Laurie remains isolated to the end.

Following Gilfillan’s medical examination in Kalamazoo in 1930, her doctor prescribed a period of hospitalization for a nervous disorder; from this point, biological explanations continued to be sought to explain her unusual behavior. In 1931, following her stay in Avella and Pittsburgh, Gilfillan was again hospitalized, this time for malnutrition. Instead of returning to New York, she went home to Kalamazoo and unsuccessfully struggled to write her book, although she produced one chapter that Putnam sold for $300 to the magazine Forum. But her behavior became erratic once more; her symptoms included sudden rudeness, insomnia, impulsiveness, and a writing block that produced both a fear of failure and suicidal moods. She complained of a pain in her head that had lasted for more than a year, which she convinced herself was caused by vertebrae twisted out of shape at the base of her skull that pressed on a nerve center, the result of years of nervous tension. She called this affliction “sciatica neuritis” and thought that an operation to rectify the condition would make her more personally stable. In June 1931 she met a rambling poet at a Kalamazoo literary gathering, fell violently in love with him, and brought him home to live with her, thus precipitating a family crisis. Within days the man fell ill, was hospitalized, and then was forcibly taken back to Canada by his father, after which he apparently died.

In a distraught state, Gilfillan went to Chicago, where she believed the poet had left some manuscripts. A few months later she was again taken ill and returned home. This time she renewed an acquaintance with an old high school classmate, Clarence Young, an aspiring novelist who took a job as a handyman in the Gilfillan home. Young nursed and guided and harassed Gilfillan into writing I Went to Pit College during the winter of 1932–33. By the time the manuscript was completed, George Putnam had quit the publishing business, leaving Gilfillan herself to bring the work to New York City in the spring of 1933. Once there, she supported herself by taking jobs in department stores and kitchens while the manuscript was making the rounds to publishers. She sold another narrative, “Weary Feet,” based on her new experiences.36

Her life becomes sketchier following her marriage in 1934, the publication of her book, and her appearance at the John Reed Club meeting. In the summer of 1934 she participated in a New Masses symposium on Marxist criticism,37 and she won a fellowship to the Bread Loaf Writers Conference in Vermont. In February 1935 she published two more pieces, a portrait of her life residing near Union Square (in which she appears as a single woman) and the satirical essay on women and Communism in the Modern Monthly.38 She signed the call for the Communist-led First American Writers Congress and joined the League of American Writers. To her friends and relatives, she announced her plans for a new book, based on the character of one Jimmy-the-Jockey, who had lived next door to her in Chicago.

On 18 August 1935, however, Gilfillan was taken by friends to a New York City hospital after she was discovered talking to imaginary characters from her new book. She was then brought back to Kalamazoo, and in October she was hospitalized at the University of Michigan in Ann Arbor. Over the next thirty-nine years, Gilfillan remained hospitalized primarily at the Kalamazoo State Hospital for the Insane, where she was treated with electric shock and insulin therapy and possibly underwent a lobotomy. In 1973 she showed small signs of improvement and was placed in a boardinghouse in Kalamazoo where five years later, at age sixty-nine, she died in obscurity.39 Her only writings that survive from this entire period are some short notes to her aunts thanking them for gifts in the late 1930s; they were signed Harriet, rather than Lauren.

Gilfillan’s diaries, which commence when she was fourteen, demonstrate that from an early age she used a highly dramatized imagination to take control of her life—to give it order—amidst a social and personal world of increasing confusion. The confusion was probably exacerbated by the social upheaval of the Depression, but there were more personal matters as well. Family correspondence indicates that in the 1920s, her older sister, Frederika, was removed from Smith College and hospitalized after suffering from delusions. In the mid-1930s her father, Edward, was advised by doctors to leave Kalamazoo and move to Chicago after he experienced violent obsessions regarding his wife as well as developing a compulsion to spank his children. Genealogical research on the Gilfillan family—which turns out to be Scottish, not Irish, as the newspapers had claimed—reveals a long history of “talented” members, sometimes poets, who are just as frequently described as “unbalanced.”40 Harriet’s (or Lauren’s) affliction seems to have been genetically inherited. Is the narrative of her remarkable journey in search of an “other America” and her rejection of middle-class values simply the work of a madwoman?

Edmund Wilson, in his writings collected as The Wound and the Bow (1941), uses the Greek mythological character Philoctetes—with his incurable wound and invisible bow—as a symbol of the creative artist. Wilson’s image of torment producing art may have application to Gilfillan, but this is not to suggest that mental illness generates creative talent. Rather, a central feature of Gilfillan’s writing is her remarkable recognition that her unconventionality, in part her mental instability but also her refusal either to be middle class or to give herself wholly to some fantastic and romanticized vision of the working class, was both her strength and her dilemma. I Went to Pit College mocks the less mature persona, Laurie; it courageously exposes Laurie much as it insists on her tenuous autonomy, harnessing her uncertain sense of self to prefigure the complex self-consciousness of James Agee and Walker Evans’s far better known Let Us Now Praise Famous Men (1941).

Beyond that, however, I Went to Pit College is a text that redelineates the proletariat in a new borderland of the class struggle, one in which boundaries and norms are destabilized. Gilfillan, who came from the bottom rung of the middle class and a very dysfunctional family, sequentially assumed new identities ranging from an indigenous street urchin to an elite and pampered collegian to an irresponsible “art for art’s sake” Bohemian to a suspected company spy. At the same time, her vision of America became transformed through her encounter with ethnicities and members of the working class that had not been part of her Smith College education. Her creative tropes—her bendings of borders, genders, and genres—were an expression not of madness but of the power of the creative imagination in the service of a humanizing art, to overcome the tragic consequences of biology. Both Gilfillan and Henry Roth left their mark on the 1930s. Roth’s work will endure, but Gilfillan’s has been lost to all but a handful of scholars.

AN ORDINARY LIFE

Not all disappearing acts were as spectacular as Roth’s and Gilfillan’s. Of the hundreds of young writers drawn to the pro-Communist movement, few had the talent that Roth displayed or the phenomenal instant success of Gilfillan. The career of Joseph Vogel (1904–90) is more representative of that of rank-and-file pro-Communist cultural workers. Like many others, Vogel was bonded to the Communist movement not as a Party activist but through his membership in Communist-led organizations, such as the John Reed Club in the early 1930s and the League of American Writers after the Popular Front, as well as his circle of friends on the Federal Writers Project. Their primary struggle was to find a way to keep writing and publishing with few financial resources and little or no institutional support, outside the occasional windfall from a patron. A profile of Vogel’s career reflects the press of daily activities and work of writing, which became central in his drift away from the movement.41

Vogel was a warm and gentle man whose first novel, At Madam Bonnard’s (1935), created the atmosphere of a Bohemian rooming house in the early Depression. His father, Morris Vogel, was a Jewish immigrant from Warsaw, Poland, who worked on the streets of New York pushing a scale on which people could weigh themselves for a penny. He then delivered milk for the Borden Milk Company using a horse and wagon. Finally he became a housepainter after the Vogels relocated to Utica. The family, while Jewish, was unconcerned with religion and attended services only two or three times a year.

Both of Vogel’s siblings dropped out of school at an early age, but Vogel was remarkable in childhood for his extraordinary capacity for reading and writing. At four he was copying whole sentences from newspapers and was soon promoted a grade. He started taking several books a week out of the library, devouring them in the evenings. He also developed a knack for eavesdropping on

JOSEPH VOGEL in 1940. A promising novelist of the Great Depression era, he drifted into obscurity in later decades. (Courtesy of Joseph Vogel)

adult conversations while reading, which provided him with a store of material he would use when he began writing creatively.

Vogel graduated from the Utica Free Academy in 1922, specializing in drafting and printing as well as taking college preparatory classes. By chance he enrolled at nearby Hamilton College and worked his way through school as a waiter, librarian, tutor, and designer of wall charts for a geology professor. Prior to attending college Vogel had systematically read a large number of classic works of fiction, but he was particularly transfixed by Fyodor Dostoevsky, who inspired his first stories. Although Vogel’s early efforts saw publication and even won prizes, his writing teacher at Hamilton declared that he must have gotten his material from “the sewers,” a comment that in part prompted Vogel to switch to a major in philosophy.

Upon graduation from Hamilton, he turned his back on his earlier aspiration to study law and moved to New York City, where he held a long series of jobs for economic survival. He worked on a daily trade paper covering the men’s clothing business; but his literary interests were too distracting, and he was fired. He then signed up as a crewman on an Italian ship taking a load of wild mules to Italy; this adventure became the subject of his first unpublished novel, of which some sections appeared as short stories. Next he edited his own publication in the clothing industry, meanwhile making a small name for himself with fiction he published in little magazines. In 1929, the year his magazine folded and he was married, the poet Louis Zukofsky (1904–78) approached him as an emissary from Ezra Pound, who was seeking promoters of his work in the United States. For a while Vogel corresponded with Pound, but he broke off the relationship when he became aware of the bizarre nature of Pound’s economic theories.

For three years in the early 1930s, Vogel worked in a New York art gallery and bookstore hanging exhibitions, selling books, and writing pamphlets about artists. After that he worked as a shipping clerk, a researcher for a professor, and a part-time teacher of journalism in a private business school. Finally he had a breakthrough. Over the years he had kept up an acquaintance with a Hamilton College trustee, Charles A. Miller, who was a well-to-do banker and attorney. Miller had followed Vogel’s literary career and occasionally took him to dinner when he came to New York. Suddenly, in 1934, he offered Vogel a $100-a-month stipend to write a novel. For his topic, Vogel chose life in a New York rooming house just before the onset of the Depression. At Madam Bonnard’s was a literary success, although sales were modest and Vogel, now the father of a young daughter, was still plagued by lack of a steady income.

Vogel had considered himself a radical while at Hamilton, and among the places to which he successfully submitted his early work was the New Masses. This caused his classmate, the psychologist B. F. Skinner, to record in his autobiography that “Vogel was contributing to a communist magazine.”42 The magazines where Vogel published fiction—Blues, Morada, Blast, and Anvil—were generally associated with the Left, and many of his acquaintances were pro-Communist. Since writers in the Soviet Union were supported by the writers’ union and could devote themselves full-time to their writing, Vogel fantasized that they lived in paradise. However, the struggle to earn a living and work hard at his writing was so time consuming that he did little more than discuss revolutionary politics. But politics did not determine his literary strategy; he always saw his artistic project as the creation of characters. In 1935 he wrote to Horace Gregory, who had reviewed At Madam Bonnard’s, that “the test of good work is the creation of revealing characters; in a book like Man’s Fate the incidents alone are sufficient to raise it above the level, but it is Malraux’s creation of characters that raises the book to greatness.”43

Vogel’s next job was as a “relief investigator” for a public welfare office in Brooklyn, which paid about $100 a month. Vogel was assigned to what was dubbed the “silk-stocking district,” where persons who had once earned a high income had been humbled by the Great Depression and were compelled to apply for welfare aid. Vogel interviewed applicants from this area and then wrote their case histories. Although Man’s Courage (1938) was far from Vogel’s thoughts at the time, the experiences he gained proved useful in writing the novel.

Once again, Vogel’s benefactor, Charles A. Miller, came to his rescue when the Munson-Williams-Proctor Institute of Utica was organized with Miller as chairman of the board. Vogel was again offered $100 a month, this time as a creative writing fellowship. Vogel moved back to Utica, to an upstairs, back-door-entrance apartment, and planned his novel about a poverty-stricken Polish immigrant family. With his prior experiences in the welfare system and his choice of his hometown for a setting, Vogel literally wept as Man’s Courage poured from him. The manuscript took little more than a year to complete and was published by Knopf to rave reviews. The New York Times carried one that began by calling the book “a novel of distinguished power” and concluded, “This novel takes first rank in this year’s fiction.”44

After the completion of Man’s Courage, Vogel spent two weeks at the Yaddo artists’ colony, where he began planning his next novel about a young man going away from home for the first time and encountering a world of violence unexpectedly connected with his own family. Upon returning to Utica, Vogel started writing the novel, which he set in an imaginary amusement park north of Utica, near a village he dubbed Bridal Veil. The Straw Hat, which suggests a new, psychological direction in his art, was published by the left-wing house Modern Age Books in 1940.

When Vogel returned to Brooklyn in 1938, he expected to resume his welfare office job; but during his long absence the department had been taken over by the civil service, and he was told to wait until the next series of exams was given. He then turned to the Works Projects Administration (WPA),45 hoping to find an assignment that would allow him to write his own material. Instead he was assigned to the folklore department, which required that he walk the streets of Brooklyn to gather children’s songs about jumping rope and bouncing balls. He quickly accepted another offer from Charles A. Miller, but this time to assist in the preparation of Miller’s autobiography. Again the salary was $100 a month, and Vogel’s task was to type Miller’s dictation.

Soon after he completed this job, in 1940 Vogel accepted employment as a prison guard with the U.S. Bureau of Prisons. He hoped to gather enough material in a few months to produce future articles and books. Instead, a lack of alternative prospects for economic subsistence led him to spend the next quarter of a century working, mostly as a counselor, at the federal penitentiary at Lewisburg, Pennsylvania; the Federal Correctional Institution at Milan, Michigan; the National Training School for Boys in Washington, D.C.; the Federal Prison Camp at Maxwell Air Force Base in Montgomery, Alabama; Kilby State Prison in Montgomery, Alabama; West Virginia Penitentiary in Moundsville, West Virginia; and the Ohio Penitentiary in Columbus, Ohio. During these years Vogel continued to publish when and where he could, in periodicals such as True Detective and publications related to his profession, such as the Juvenile Offender. As a result of many years of chain-smoking, Vogel suffered a heart attack in 1964 and decided to return to more sustained efforts at writing. He found work teaching English composition at Ohio State University, and after a year he was given classes in advanced expository composition and narrative writing. Before he retired in 1970, he had published a play and a piece called “Prison Notes” in the literary magazine of the English Department. After that, Vogel devoted himself to creating handmade lettered books with the texts from Lewis Carroll and James Joyce. As in the case of numerous other rank-and-file participants in the literary Left, few knew that Vogel was still alive or that he had returned to his art.

FROM NEW MASSES TO MASS MARKET

Even a writer with a national reputation and who made a good living through sales of his or her work could mysteriously disappear. Of all the pro-Communist writers who made the transition to mass culture during the antifascist crusade, Ruth McKenney (1911–72) is the one whose fame was greatest and the one who plummeted the farthest. She was born in Mishawaka, Indiana, and grew up in Cleveland, Ohio. Her mother, Marguerite Flynn, was a public school teacher and an Irish nationalist. She encouraged Ruth toward radical politics but died when her daughter was eight. John Sidney McKenney, her father, was employed as the manager of a factory. It was a sad childhood, and Ruth discovered how to disguise her unhappiness with humor.

Ruth McKenney attended but did not graduate from the Ohio State University in the late 1920s. Journalism was her passion. At age fourteen she began working on the Columbus Dispatch; she first learned the trade of printer and then, at seventeen, switched to reporting. In 1932 she started writing for the Akron Beacon-Journal and soon won awards for her feature reportage. Her radicalism became more pronounced as the Depression evolved. By 1933 she had a reputation as an independent Leftist and a good reporter who wrote funny stories, some of which exhibited the influence of humorist James Thurber, who had preceded her at Ohio State. Along with another Leftist, B. J. Widick, she organized the Columbus local of the Newspaper Guild, and Widick became its vice president. Widick remembered her as looking “Shanty Irish, vivacious with a mug face, heavy set and unhappy about it,” and that she sometimes had the trace of a snarl on her face.46 Widick also recalled that the men on the paper were quite jealous of her abilities, and that she was strongly supported by Jack Knight, owner of the paper.

By the mid-1930s McKenney was drawing close to the Communist Party and was much influenced by Heywood Broun, a Communist fellow traveler and a leader in the Newspaper Guild. With encouragement from the noted columnist Earl Wilson, McKenney moved to New York City and spent 1934 to 1936 employed as a feature writer on the New York Post. Subsequently she used her savings to launch herself as an author.

McKenney’s first writings would be her best-known. These were short stories about her zany younger sister, Eileen, that initially appeared in the New Yorker starting in 1936. The wittiest were collected in her inaugural book, the bestselling My Sister Eileen (1938). In 1940 Eileen McKenney moved to Hollywood, where she married novelist Nathanael West, but the newlyweds were killed in a car accident in December of that year. The play version of My Sister Eileen opened only a few days later, in early 1941, and subsequently become a smash hit. Then a movie was made of it in 1942, a Broadway musical called Wonderful Town appeared in 1953, and a new film based on the musical came out in 1955. McKenney wrote many other madcap tales about her family that appeared in three subsequent collections: The McKenneys Carry On (1940); The Loud Red Patrick (1947), which also became a Broadway show; and All about Eileen (1952). Less successful were two autobiographical humor books about her later life, Love Story (1950) and Far Far from Home (1954).

Like Len Zinberg, McKenney learned very early to present a Marxist sensibility in forms accessible to a broad audience. My Sister Eileen provides many episodes in which the “truth” of experience is counterpoised to cultural myths that usually stem from institutionalized religion and the commodification of culture. Even though the work is a contribution to popular culture, McKenney repeatedly satirizes mass culture, such as the movies, which are said to attain value from a strictly consumerist point of view because they last longer than other forms of mass distraction. On the other hand, sometimes mass culture tells more about social reality than the versions offered by the cultures of family and church, as in the case of the “Chickie” cartoon featured in one episode. Rebellious behavior is the source of much of the humor of the tales, and such behavior is also valorized as superior to the foolishness that prevails among those who carry out their social roles unthinkingly. This unthinking quality is suggested by those whose lives are regimented in the summer camp that Ruth and Eileen attend. Implicit Communist attitudes are sometimes present in passing, as when Ruth acquires anticapitalist and atheist values from a robust unionist organizer. So are quasifeminist opinions, as when Ruth’s father, fascinated by capitalist gimmicks, is outsmarted by his clear-thinking daughter. In sum, the My Sister Eileen tales can be regarded as the story of the making of two inner-directed female rebels, during which the antinomies of mass culture are interrogated in a mass culture form.

In 1937 Ruth McKenney married a prominent Communist journalist, Richard Bransten, who used the pen name Bruce Minton. After Eileen McKenney’s death, the couple adopted her son from an earlier marriage as well as Bransten’s son from his first marriage; they also had a daughter of their own, named after Eileen. McKenney’s political views were as ardently Communist as her husband’s, and during the late 1930s and early 1940s she had her own weekly column, called “Strictly Personal,” in the Party’s New Masses.

McKenney considered her humor writing as merely a source of income, “to make a living while composing weightier opera.”47 The first of her “weightier” works was a nonfiction novel called Industrial Valley (1939), based on events in Akron from 1932 to 1936. The documentary form of the work, which uses experimental techniques to dramatize the Goodyear rubber strike and the beginnings of the CIO, led the New Republic critic Malcolm Cowley to declare it “one of our best collective novels.”48 Jake Home (1943), her second proletarian novel, was less enthusiastically received by the popular press and even caused a controversy in the pages of the Daily Worker.

Jake Home commences with the extraordinary, agonizing, three-day Cesarean birth of the twelve-pound Jake in 1901. It concludes with the third or fourth in a series of traumatic personal-political rebirths wherein Jake finally assumes his role as a working-class Communist leader. The overall style of Jake Home is much in the mode of John Dos Passos, a one-volume U.S.A. without the experimental interchapters. McKenney includes events in Pennsylvania, New York, Chicago, and the far West and dramatizes historical events such as the 1919 steel strike and the Sacco-Vanzetti defense campaign. There are suggestions that Jake is an embodiment of the leadership potential of the working class in the United States, perhaps an alternative to Dos Passos’s character Mac in U.S.A. Her fast-paced, realist-naturalist prose technique catches the flavor of many decades, and her sketches include a range of familiar and symptomatic personality types. But her work is also similar to Dos Passos’s in that she never quite achieves emotional depth in her main characters.

A primary source of contention among those who sent letters of complaint about the novel to the Daily Worker was McKenney’s proletarian übermensch, Jake Home, who is tempted into co-optation by two women. One is Margaret, an upwardly mobile western Pennsylvanian; the other is Kate, a rich New York socialite who is slumming in the Communist movement. It was accepted by readers that effeminacy, literary interests, and sensuality were linked to middle- or upper-class corruption; the objections were to the lack of decent Communist women in the novel. The women in Jake Home never share Jake’s fundamental loyalty to the working class. His first wife, Margaret, is simply unaware of his formative proletarian experiences; she marries him in ignorance of his underlying values. Treated with little sympathy by McKenney, Margaret is depicted as a corrupt hypocrite who has sex with Jake twice during her visit with him when she is supposed to be finalizing her divorce so she can marry a wealthy industrialist.49

Jake’s second wife, Kate, is depicted as no less savory but is seen more as a victim of her class background. Kate enters the relationship with a full awareness of Jake’s political convictions and, indeed, is drawn to him precisely for that reason. Moreover, Kate has outspoken feminist attitudes, declaring herself sexually a free agent and refusing the role of a “breeding machine.”50 However, Kate’s umbilical cord to wealth and privilege prevents her from full integration into the Communist movement, despite her Party membership, as well as integration into her marriage to Jake. Kate’s “infidelity” to the Communist cause is paralleled by her sexual infidelity to Jake, which usually occurs with wimpy, literary males.

Jake Home was intended to be a study dramatizing why a talented person who might rise to wealth as a boss or bourgeois politician would throw in his or her lot with the working class. It seemed, however, also to reflect McKenney’s and Bransten’s need to purge bourgeois ideas and temptations from their consciousness. The depiction of Jake as having a clear conscience and finding fulfillment only when he repudiates class corruption expresses the ideal that they sought but were incapable of sustaining.

From a regional perspective, western Pennsylvania functions primarily as a background in the novel. It is the proletarian cradle of Jake’s Communism, distant from the fleshpots of New York, and the memory of his origins holds Jake steady.51 The feminist politics of the book are hardly revolutionary; McKenney advances a progressive liberal view of gender relations in the home. The perspective is the same as that proposed in her autobiographical Love Story: A woman has a right to a career and a family; this can be hellishly stressful but is still a step forward from the traditional role of women in the nuclear family. However, the husband must share domestic duties, and it is strongly desirable to have modern appliances and maids, cooks, and nursemaids.52

The Daily Worker debate about Jake Home demonstrates the ongoing use by many Communist reviewers and activists of political criteria to judge fiction, and their obsession with the need to create admirable Communist leaders in fiction. At first the novel was overpraised, and then two Communist political militants—Peggy Dennis, the wife of leader Eugene Dennis, and Israel Amter, an admired leader in New York—attacked her portraits of Jake and Kate as miseducating the American public as to the real character of Communist leaders. There may be such individuals in the movement, the two insisted, but they would not be leaders. McKenney defended herself by stating that the depiction of Jake Home was the first part of a trilogy, and that his subsequent development would fulfill expectations for a man of his political stature—including the appearance of a loyal wife and family. As for Kate, she was not a wicked woman but one to be pitied because she lacked the strength to carry out the life required by Communist convictions.53

In her memoirs, McKenney reported that the criticisms were an all-out assault—Jake was “kicked black and blue” by the Daily Worker. In reality, most of the specific objections were couched in respectful praise showered on other aspects of the novel, and on her talents in general. McKenney’s Daily Worker reply at the time expressed gratitude for the attention given to the novel and considerable humility, peppered with obsequious references to the Communist Party leadership and a quotation from Stalin. Yet in her memoirs she reported that she was “heart-broken.” She had apparently regarded Jake as an “immortal” hero, and she had shown a draft to important Communist leaders in the labor movement as well as in the Party literary circles. Her explanation for the uproar was that “a famous personality in the left-wing movement” had let it be known that Jake was “a mean, nasty, overheated version of himself.” Years later, McKenney concluded that she got what she deserved. She had attempted to fashion a novel to serve a cause and had been judged by the criterion of how “useful” the book might be to the cause.54 A year after the debate, Ruth McKenney and her husband were living in Hollywood and collaborating on film scripts. Bransten planned to write a scholarly tome on economics; McKenney, a new novel about wartime Washington. Neither materialized.

During 1945 and 1946 the Communist Party was in turmoil as the Party’s leader Earl Browder was accused of right-wing deviations, replaced, and cast out. Bransten and McKenney were publicly expelled a few months after Browder, although the accusation against them was “ultraleftism”; they were charged with being part of a faction that felt that the anti-Browder correction had not gone far enough. Subsequently McKenney and Bransten took their family to Western Europe to avoid the conservative atmosphere sweeping the United States with the onset of the Cold War. They eventually settled in England, and from there they coauthored a very successful travel book, Here’s England (1950).

However, both were tormented by personal demons. Bransten committed suicide on McKenney’s birthday in 1955, just before McKenney’s last major work appeared. Mirage (1956) was a pedestrian historical novel about Napoleon in Egypt. A few years later McKenney returned to the United States, where she was periodically institutionalized for depression. Suffering from a heart ailment and diabetes, she died at Roosevelt hospital in New York at age sixty-one.

McKenney resembled Len Zinberg in holding a dual identity as a proletarian and a popular writer; yet their dispositions did not match. By all accounts, Zinberg declared that there were no contradictions between the two; as Ed Lacy he was pursuing Len Zinberg’s life as a literary radical by other means. McKenney, in contrast, asserted that she was conflicted; her successful popular writing was merely a means of making easy money to sustain her serious, proletarian work. Other writers who found a home in mass and popular culture as the climate of the antifascist crusade mutated into that of the Cold War would offer a variety of other explanations for their choices. What is evident is that the conversion of proletarian writers from the New Masses to the new mass market did not require an abandonment of aims, only a new literary venue. A comparable conclusion might be drawn from a survey of the large number of Jewish Americans who converted to the internationalism of the antifascist crusade. For the most part, the conversion of the Jews neither obliterated nor fully obscured where they had come from.