6

The Conversion of the Jews

THE LOST WORLD

In a 1985 study in the New Left Review, “The Lost World of British Communism,” the British Marxist Raphael Samuel recalled his upbringing in a Jewish Communist family in the 1930s and 1940s. Samuel wrote that to be a Communist was to have “a complete social identity.” He recollected that, like practicing Catholics or Orthodox Jews, “we lived in a little private world of our own,” which he described as “a tight . . . self-referential group.” Samuel and his circle “maintained intense neighborhood networks and little workplace conventicles.” They “patronized regular cafés, went out together on weekend and Sunday rambles,” and took their holidays together at Socialist Youth Camps. They even had their own “particular speech. . . . Like freemasons we knew intuitively when someone was ‘one of us,’ and we were equally quick to spot that folk devil of the socialist imagination, a ‘careerist,’ a species being of whom I am, to this day, wary. Within the narrow confines of an organization under siege we maintained the simulacrum of a complete society, insulated from alien influences, belligerent toward outsiders, protective to those within.”1 Aaron Kramer (1921–97), a Jewish American Communist for two decades and a prolific poet who secured his reputation after the 1930s, conjured up a similar “lost world” when he reminisced about his own youth in the 1930s and 1940s.2

Kramer was born in 1921 to New York working-class Communist parents, Hyman, a bookbinder, and Mary, who, in the Great Depression, stamped laundry tickets. The Kramer family idolized Moissaye Olgin (1878–1939), for many years the Communist Party’s leader in Jewish affairs and the most notable figure of that era in the Party’s Yiddish-language daily newspaper, Freiheit. In 1931 Kramer was sent to an ultra-Bolshevik Yiddish School where his instructor had recently arrived from the USSR. In Kramer’s public elementary school, teachers would ask the students for the “news of the day”; most read from the New York Times, but young Kramer leaped to his feet with the Daily Worker in hand. In 1990 Kramer recalled that his favorite “newsday” was always the day after 1 May, when he could announce to the class, “‘A million people marched in this city, a million people marched in that city, fifty thousand here.’ . . . That was my text, and it remained my text for a very long time.”3

Kramer’s impulse to write poetry emerged independently, but as he approached adolescence, it was harnessed to his revolutionary political spirit. Kramer’s mother, who nearly outlived him and remained a Communist Party stalwart to the end, reported that at age two he was reciting rhymes, many inspired by the Yiddish, folk, and labor songs she sang. In first grade, at Public School No. 174 in the Bronx, Kramer wrote his first poem, a Mother Goose–inspired verse about a boy in a haystack. This came at the urging of Pearl Bynoe, the only African American teacher in the school in 1927 and probably the only Black person most of the all-Jewish class of students had ever seen. Kramer felt such gratitude toward Miss Bynoe, along with developing a mad crush on her, that forty-seven years later he established a poetry prize in her name for the student population of the school, now entirely African American and Latino/Latina.

Bynoe’s encouragement launched him, at age six, into an outpouring of nature poems. Initially, Kramer did not realize that he was unique in the intensity of his reactions to nature, to the sound of a train, or to the sight of the bricks on a building in an old town in Connecticut that he passed by. “I thought all children reacted that way and had a sort of romantic haze around the things that they saw.” The “nature phase” lasted through fourth grade. Then he experienced a clash in his emotions between the self-indulgence he associated with his immersion in nature and the seriousness he felt was demanded of him by his Marxist political environment. The resulting transformation was no doubt assisted by his first sighting of the poetry editor of the Communist children’s magazine, New Pioneer—Martha Millet, about five years his senior and “an absolutely gorgeous creature.”4

Overnight, Kramer tore up his notebook of nature poems and issued a ringing manifesto of socially conscious art:

Now is not the time for nature poems

When thousands upon thousands

Are losing their homes.

Not ballads of how princesses wed

When the problem is, “Where shall I find bread?”5

This annunciation of a new direction was promptly submitted to the New Pioneer, where Kramer became the principal poet for several years, until he graduated to the children’s page of the Sunday Daily Worker.

Kramer was raised in Yiddishkeit, yet a chief theme of his poetry through the

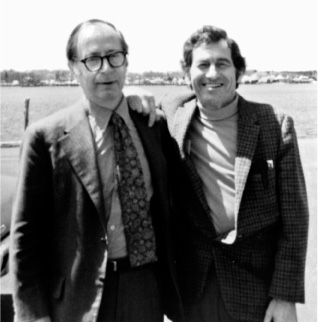

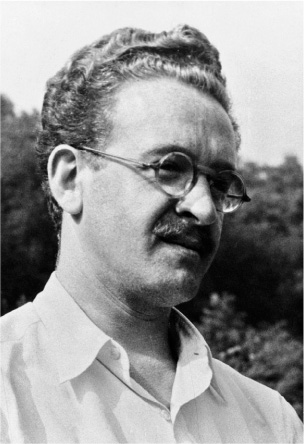

AARON KRAMER AND NORMAN ROSTEN were pro-Communist poets in the 1940s and remained friends during and after the Cold War. (Courtesy of Aaron Kramer)

1940s and early 1950s—and a strong presence even after that—was African American history and culture. Indeed, his poems in the New Pioneer included one on the Scottsboro case and another addressed to the imprisoned Black Communist Angelo Herndon. The latter begins

You youthful proletarian,

Of an oppressed and starving race;

Your hardships are the hardships

That all working youth must face.

It was signed “Aaron Kramer, 121/2.”6 The choice of Black rather than Jewish identity, to the extent that Kramer would later insist that he “felt Black” and that he glowed with pride when a Black writer said, “Kramer, you have a Black soul,”7 is partly explained by personal factors. These encompass his infatuation with Pearl Bynoe and the Communist political education he received through supporting the Party’s defense of Angelo Herndon and the nine Scottsboro Boys. A facilitation of this cross-ethnic identification may also be associated with the decision of his parents to identify themselves as Yiddish but not Jewish.

Such a perspective was a point of principle in his family, as it was among many pro-Communist Freiheit readers, and also for the popular Proletpen writers —Jewish Communist working-class poets writing only in Yiddish, such as Yuri Suhl and Ber Green, who took the adolescent Kramer under their wing.8 The Kramer parents spoke Yiddish, sang Yiddish, and ate Jewish foods (which they called Yiddish foods) but were not merely irreligious or nonreligious; they were actively antireligious. Living in a ground-floor apartment, they made a point of leaving their shades up so that the Orthodox Jews en route to the synagogue could see them eating on fast days. The Maccabees were worshiped as national liberation fighters, but Hanukkah, the Festival of Lights, was not celebrated. In fact, Kramer never missed a day of school during the Jewish holidays; in many classes he was the only child, staying all day and insisting on being taught, as an act of defiance.

Yet the Kramer family was not assimilationist. Like Proletpen and other Freiheit readers, the Kramers had no interest in taking on the dominant Christian bourgeois culture. Instead, they wanted to be internationalist and working class. The distinction to them was between dragging themselves back to their childhood memories and shtetl culture or looking forward to the future and fighting the oppression they faced today and would face tomorrow. From this perspective, the paramount issue in the United States became Jim Crow, anti-Black racism, and the struggle for liberation of Black Americans, who were indubitably working class, bearers of a rich and inspiring folk culture, and up against proponents of white supremacism that bore a striking resemblance to the ideology of those who carried out pogroms under the czar and fascist assaults under Hitler. “Yiddish but not Jewish” could mean, under these conditions, varieties of a Jewish identity integrated into an internationalist outlook, a standpoint scornful of Judeocentrism or Jewish chauvinism yet comfortable with Jewish secular traditions and history.

This brief profile dramatizes some of the salient features of the Jewish American experience with Communism, especially that of first- and second-generation Eastern European Jews. The inordinately large number of Jews in the intellectual apparatus of the Party as well as the panoply of cultural networks that appeared as part of the broader social movement was a pronounced feature that grew even more obvious during the antifascist crusade when Aaron Kramer found his poetic voice. How large was the Party’s Jewish American constituency? Reliable statistics are difficult to obtain, but there was possibly a Jewish American presence of close to 50 percent of the total of those who published regularly in Party-affiliated venues and joined Party-led organizations such as the John Reed Club, the League of American Writers, and the National Council of the Arts, Sciences and Professions. This is a remarkable aggregate; only 2 or 3 percent of the population of the United States was Jewish in the mid-twentieth century. Some Jewish American writers, like Kramer, came from Communist families; many more came to Communism by choice, albeit in numbers disproportionate to those for the general population. The justification for such an inordinate Jewish presence may be ascribed to manifold circumstances. These provide an explanation for the flow of Jewish Americans as a group into the Communist movement; what triggered the individual choices of particular writers can only be understood through case studies.

The most compelling explanation for the high proportion of Jews is simply that the Communist movement in the United States had a solid foundation in Eastern European Jewish immigrant families; they brought to their new country not only an abhorrence of czarist autocracy but also working-class and socialist loyalties. Moreover, the Communist movement exhorted its members to adhere to a cultural pluralist and internationalist universalism, a stance that was attractive to young Jews emerging from families still shaped by the experience of shtetl and ghetto isolation. In contrast to the strict faith of their Orthodox elders, Marxist doctrine furnished the option of a moral life justified by supposedly scientific arguments and analysis. Jews nurtured by an atmosphere influenced by the study of holy books and ardent debates over segments of the Old Testament were well equipped for a political movement where hallowed writings by Marx, Engels, Lenin, and Stalin were fervently embraced as well as debated as guides to political practice. Such intellectually passionate individuals were excluded from many typical professions by anti-Semitism and the constricted economy of the Depression, while Communist institutions and organizations afforded a place to write, speak, teach, and interact on equal terms with non-Jews. In fact, a Jew entering the Communist movement had a range of choices through which to express his or her identity. On one hand, there were clubs and organizations immersed in Yiddishkeit; on the other, one could also assume a non-Jewish “party name” and a persona devoid of any ethnic attachment.

In the 1930s and 1940s, of course, the Communist movement was among the most aggressive forces in striving to prepare a response to the march of fascism across Europe. The effect on Jewish Americans can be seen in the large number of Jewish American youth who volunteered to battle the combined military might of Franco, Hitler, and Mussolini in Spain in 1936 by joining the Party-led Abraham Lincoln Brigade. Once overseas, they joined thousands of other Jewish internationalists from Europe and the Middle East to aid in the creation of a people’s army that comprised the International Brigades under the leadership of the Communist International. The chief ethnic component of this initial campaign to halt fascism by military force of arms was most likely Jews from numerous countries. Yet most of the Jews in the Abraham Lincoln Brigade regarded themselves primarily as antifascists and partisans of democracy, which is also representative of the frame of mind of most Jewish American Communist cultural workers until the post–World War II years. Of course, when the nonaggression pact was suddenly signed between Hitler and Stalin in August 1939, the Party endured profound embarrassment. Then Germany invaded the USSR in June 1941, and antifascism was restored as a major Communist theme. As the Party leaped to the forefront of supporting the Allies in World War II, a younger generation of Jewish American cultural workers emerged.

Antifascism was vital, but left-wing Jewish cultural workers also adhered to other convictions that comprised an interlocking worldview. These include an exorbitantly romanticized assessment of the USSR, a zealous championing of the CIO, and a burning abhorrence of white supremacy. From 1936 to 1939, belief in the Soviet Union’s steadfast antifascism certainly enabled many Jews to blind themselves to the criminal nature of the Moscow Trials; then, from September 1939 to June 1941, belief in the ultimate goodness of the Soviet Union was no doubt an important factor in the rationalization by many Jews of their acceptance of the eighteen months of the Hitler-Stalin Pact as a temporary tactical maneuver. What was perhaps singular in Jewish American left-wing antifascism was the political form it took: Jewish nationalism and any dependence on powerful Western protectors were eschewed; instead, Jewish Americans called for unified armed resistance among all the oppressed and expressed a sense of sympathy and solidarity with other non-Jewish groups suffering persecution, especially through colonialism and white supremacism. Their blind spot regarding anti-Semitism in the USSR flowed from the Soviet Union’s status as a bulwark of social justice, not from insensitivity to Jewish suffering.

BETWEEN INSULARITY AND INTERNATIONALISM

Communism’s appeal for Jewish American cultural workers profoundly affected intellectual life in the United States in the mid-twentieth century. Prior to the 1930s, the foremost authors in radical literary circles were the non-Jewish writers Jack London, Upton Sinclair, Floyd Dell, John Reed, and Max Eastman. During the Depression, when Communism displaced Socialism as the leading force on the Left, there was a sea change in the number of left-wing Jewish participants. A former playwright and journalist, Michael Gold, achieved international renown when his Jews without Money was published in 1930. Clifford Odets (1906–63) revolutionized the theater with Waiting for Lefty (1935), Awake and Sing (1935), and Golden Boy (1937). Lillian Hellman (1905–84) promoted anticapitalism with The Little Foxes (1939) and antifascism with Watch on the Rhine (1941). A legion of radical Jewish American poets emerged, such as Stanley Burnshaw (1906–2005), Joy Davidman (1915–60), Kenneth Fearing, Sol Funaroff (1911–43), Alfred Hayes (1911–85), Edwin Rolfe, Muriel Rukeyser (1913–80), and Louis Zukofsky.

Moreover, the post-Depression replenishment of the Communist literary tradition was already in progress, as the early writings of a younger group of Jewish American Left cultural workers developed from the Communist-led cultural milieu. In the 1940s, after the commercial failure of Somebody in Boots (1935), Nelson Algren, born Nelson Abraham (1909–81), won acclaim as the bard of the lumpenproletariat for Never Come Morning (1942) and The Man with the Golden Arm (1949), his novels about the Chicago urban underclass. Irwin Shaw published the best seller The Young Lions. Jo Sinclair, born Ruth Seid (1913–95), who likewise launched herself by writing radical fiction and drama (see the discussion in the Conclusion), brought out a prizewinning attack on homophobia and anti-Semitism, Wasteland (1946). Howard Fast, well regarded for his historical novels, publicly joined the Communist Party in 1943. Arthur Miller (1915–2005), a struggling Marxist playwright since the late 1930s, won the Pulitzer Prize for Death of a Salesman in 1949. Norman Mailer (b. 1923), a Communist fellow traveler, achieved both popular and critical success with his masterpiece of battle in the Pacific, The Naked and the Dead (1948). When HUAC hauled ten leading Communist screenwriters and directors before hearings in Washington, D.C., in 1947, which led to their imprisonment in 1950, six were Jews: Alvah Bessie; Herbert Biberman (1900–1971); Lester Cole, born Lester Cohn (1904–85); John Howard Lawson (1895–1977); Albert Maltz; and Samuel Ornitz (1891–1957).

Finally, the institutional presence of Jews in the cultural wing of the Communist movement was remarkable. The editor of the Party’s publishing house, International Publishers, was Alexander Trachtenberg (1884–1966); the chair of the Party’s cultural commission was V. J. Jerome, born Isaac Jerome Romaine (1896–1965); and the head of the Party’s important Hollywood section was John Howard Lawson. There was a substantial Jewish presence on the editorial board of the Party’s New Masses as well as its successors, Mainstream and Masses & Mainstream. The Party’s theoretical organ, initially called the Communist and then Political Affairs, was edited in the late 1940s and early 1950s by Jerome.

Yet what did it mean to be a Jewish American Communist if so many declared themselves as internationalists first? The Aaron Kramer paradigm offers a perspective on how varied identities—a Jewish identity, an identity expressing solidarity with African Americans, a proletarian identity, or a Communist identity—can be the basis for political activity of various types. On one hand, the insularity of the Jewish Communist cultural milieu could facilitate its participants’ adoption of a Communist outlook that was safeguarded from the effects of the dominant culture of the country or region. Thus many Jewish Marxists felt no temptation to adapt to middle-class Christian culture, detach themselves from Jewish folk culture, succumb to self-hatred, or embrace the various forms of ethnic prejudice widespread in the dominant culture of the United States. Many, although not all, especially if one’s family was educated and secularized, retained an affection for Jewish songs, foods, earthy humor, and a tradition of heretical thought and resistance to oppression. On the other hand, the largely insulated Communist culture had a selective, outward-looking component that emphasized internationalism, antifascism, anticolonialism, and a strong sense of identification with other groups at the bottom of the social ladder. The resulting ethos, a product of both insularity and internationalism, was expressed by Kramer in his life and in his poetry, and especially in his combination of a nonchauvinist Jewish pride and a crossover identity with Black Americans. A similar ethos was diversely exemplified in Kramer’s generation of Jewish Marxist activist cultural workers who were shaped by the specific problematic of the 1930s and who continued their work in the 1940s and 1950s.

In examining a range of writers and intellectuals, one finds that patterns of identity selection and construction could be constituted differently in different contexts. While the Jewish presence in the Communist cultural movement may lend itself to generalizations on a broad plane, these generalizations cannot in turn be imposed from the top on the complex individuals who comprised the movement.

Thus some Jews who took on the roles as spokespersons for the Party might ignore identity in all forms except that of a Communist. James Allen (1906–91), for instance, a University of Pennsylvania Ph.D. candidate, author of many of the Party’s scholarly tomes on “the Negro Question,” and eventually the president of the Party’s International Publishers, left behind his posthumously published A Communist’s Memoir: Organizing in the Depression South.9 Although the memoir exemplifies the characteristic sense of solidarity with African Americans, in 130 pages there is not one word about any feeling of Jewish identity, even when Allen heard blatant anti-Semitic remarks during the Scottsboro trial. His changing his name from Sol Auerbach to Jim Allen is explained only as a desire for anonymity, since he saw Jim Allen as a common name. However, when writer Irwin Granich chose to mask his own identity, he became Mike Gold—another common name but one that affirmed his Jewish background.

Perhaps in the middle of the spectrum, between Kramer and Allen, is Ben Burns (1913–2000). In 1945 Burns was the founding editor of the famous African American magazine Ebony. A Jewish American Communist who had been born Benjamin Bernstein, Burns was a man whose political convictions alone led him to antiracist journalism, which in turn placed him in contact with many African Americans who worked for the Black publications the Chicago Defender and the Negro Digest. In his 1996 autobiography, Nitty Gritty, Burns recalled frequently being told that he was “not a real white man” by John Johnson, the Black owner of Ebony, and other staff members.10 On occasion, curious visitors to Ebony’s offices would query, “Say, Burns, what are you anyway, Negro or white?” His response was “Neither—I’m Jewish.”11 This was not insignificant as an answer during the postwar era, when many Jews were identifying themselves as white.

Burns, Kramer, and hundreds of other journalists, editors, fiction writers, playwrights, scholars, film script authors, and poets belonged to this generation of midcentury left-wing Jewish American cultural workers whose sense of Jewish identity was largely informed by the belief that they shared with African Americans common goals and common enemies. Although they were antisegregationist on principle, their perspective for the most part cannot be understood as integrationist in the sense of “liberal integrationism,” denoting equality in formal political rights within the existing social system. Whether they came from Left Jewish families, like Kramer’s, or chose to link themselves to the antiracist tradition by identifying with the Communist Party was not decisive. The utopia of racial harmony to which they aspired would be forged in the process of common work not merely to “integrate” into a racist capitalist system but to overthrow the inegalitarian social system; it would be realized only in a world from which the underlying causes of racial oppression had been purged by collective action. The meeting ground for Blacks and Jews on the cultural terrain of the Communist-led social movement was envisioned mainly in the imagined narratives of left-wing plays, novels, and poetry. But in some cases it occurred in practice—on the battlefields of Spain, in clandestine meetings of self-organized and armed Black sharecroppers with Jewish union and Party organizers in the Deep South, and on the picket lines of industrial union struggles in the North.

The personal, political, and cultural commitments growing out of this movement were indissolubly linked to an ideology of antiracist radicalism as it evolved through two stages: first, in the context of the Depression and, second, during World War II and the Cold War. The view that anti-Black racism was the symptom of an inegalitarian capitalist economic order that was also dangerous for Jews and other oppressed groups was thus doubly reinforced. The rise of fascism illustrated that targeting of Jews in Europe was analogous to anti-Black racism in the United States; the era of the Cold War McCarthyite witch hunt revealed how racism, anti-Semitism, and anti-Communism were all linked as components of the assault on the Left.

Although Jewish American Left cultural workers and political activists of the generations of the antifascist crusade were passionate in their intellectualism, much of the foundation for such an ethos grew not from the study of particular party texts but from life itself, including the practice of the Party. According to Kim Chernin in her 1983 memoir, In My Mother’s House, her mother, Rose Chernin, the California Jewish Communist imprisoned during the McCarthy era, joined the Communist Party after a demonstration by the unemployed. Rose Chernin recalled that she looked up and “I could see those horses coming. It was a nightmare. And we were paralyzed. They were riding straight toward us, riding us down.” When she heard a scream, she imagined that she was “standing in a village and the cossacks were riding down.” She then added, “You could go so far back in Jewish history and always you would find that cry. Always, in the history of every people. And then people were running all around me, racing for the subway, screaming, crowding together. And I ran with them, and I was thinking, this, this is the answer they give to the demands of the people.” Chernin stood there, looking at the crowd: “My fear was gone. I felt angry, I felt exhilarated, and I felt purposeful. That was the day I joined the Communist Party.”12

Like the Kramer family, Rose Chernin was as militantly opposed to Jewish theology as she was fervently in solidarity with the Jewish people. Of Freiheit she recalled that “it was against religion and never lost an opportunity to attack the tradition.” Chernin noted further that in New York City in the 1930s there was an agreement that Yiddish papers would not come out during the Jewish holidays. Yet Freiheit appeared even on Yom Kippur, the holiest of holidays. She admired this policy and added, “To you this may not sound like anything very much, but to us it was the world turning upside down.”13

Notwithstanding the antireligious stance of Chernin and other Jewish Communist militants, the alternative moral principles they constructed in the course of their political struggles resemble the collectivist ethics found in aspects of Judaism, Christianity, and many other religions. They rejected the Jewish religion’s institutional forms but appropriated much of the moral content. Commenting on the efforts of the Party-led unemployed councils to get milk for children of Harlem and elsewhere in New York, Rose Chernin observed, “This struggle of people against their conditions, that is where you find the meaning in life. In the worst situations, you are together with people. If there were five apples, we cut them ten ways and everybody ate.”14

Despite its claim to be based on scientific analysis, the predominant pro-Communist radicalism of this era was also marked by illusions, oversimplifications, and self-deceptions. Perry Anderson identified the problem as flowing from a new form of nationalism that had emerged following the victory of Stalin’s faction in the Communist Party of the Soviet Union, based on the illusion that it would be possible to build socialism in a single, economically underdeveloped country. As a consequence, “the activities of the Third International were utterly subordinated to the interests of the Soviet state, as Stalin interpreted them.” The result was “the arresting phenomenon, without equivalent before or since, of an internationalism equally deep and deformed, at once rejecting any loyalty to its own country and displaying a limitless loyalty to another state.” The tragedy was played out “by the International Brigades of the Spanish Civil War, shadowed by Comintern emissaries—Codovilla, Togliatti, Gerö, Vidali and others—recruited from across all Europe and the Americas. With its mixture of heroism and cynicism, selfless solidarity and murderous terror, this was an internationalism perfected and perverted as never before.”15 Yet beneath this deformed internationalism, the antiracist radicalism to which Jewish Americans were attracted grew from heartfelt convictions and the situation in the United States; it was not imported from the USSR, and changes in Soviet policies did not decisively disrupt such commitments, even if tactics dramatically changed on various other fronts.

THE MIRROR OF RACE

As a chief theme in writing by Jewish American pro-Communists, the portrayal of racism against African Americans served a range of functions. Some Jewish Americans had grown up in proximity to African Americans, but segregation reigned to the extent that actual contact was minimal. Most of their African American literary characters and experiences were therefore very much imaginary constructions; moreover, the literary texts can be regarded as mirrors, in which the Jewish American writers illuminated dark others but were also bringing to life aspects of their own psyches that they did not want to engage directly. Several varieties of this complex relationship of autobiography and antiracism can be especially observed in the work of three prolific Left writers: John Sanford, Vera Caspary, and Howard Fast.

John Sanford (1904–99) used African American characters to assert his anger and outrage about the U.S. social system and to unveil his utopian dreams of carrying out some action in opposition to the system. He was born Julian Shapiro in Harlem, the only son of Russian Jewish émigrés. He was devastated by the death of his mother when he was ten; it was she who had instilled in him a love of books and American history. Emulating his father, Sanford chose a career in law and was admitted to the bar after being awarded a law degree from Fordham University in 1929.

Instead of practicing law, he fell under the influence of his childhood friend Nathaniel Weinstein, who later called himself Nathanael West (1902–40), and started submitting stories to little magazines such as Pagany and Contact. In 1934 he published The Water Wheel, a stream-of-consciousness meditation on events in the life of a law clerk in the late 1920s. The book was praised for its graceful and clear prose and original language, but it seemed formless. Under West’s influence, Sanford adopted his new name, only half-admitting to himself that it masked his Jewish identity. West had urged that “Shapiro” be changed to “Star-buck,” a character in Herman Melville’s Moby Dick, but “Sanford” seemed more suitable because it appeared to have no special significance.

In 1935, after some years living on a dole provided by his father, Sanford published The Old Man’s Place, a horrific story of a group of World War I veterans who wreak havoc on a farm. The book was characterized by power and speed as if a bomb were about to explode, suggesting the influence of Erskine Caldwell, James M. Cain, and W. R. Burnett. Its success brought him an offer from Paramount pictures, and he moved to Hollywood. At Paramount he met his future wife, the screenwriter Marguerite Roberts (1905–89). Together they shifted from Paramount to MGM in 1938 and collaborated on a number of motion pictures. Following their success with Honky Tonk, starring Clark Gable, Sanford was offered a two-year contract. Instead of accepting it, he took up his wife’s offer to stay home and write novels, living on her income.

By the late 1930s, Sanford had been drawn to the Communist Party. His first

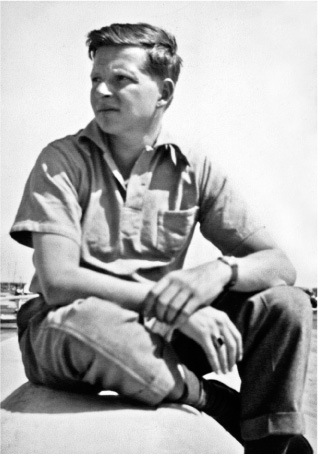

JOHN SANFORD joined the Communist Party in the 1930s while continuing to publish powerful and original novels. (From the Sanford Collection in the Howard Gotlieb Archival Research Center at Boston University)

step was to stop by Stanley Rose’s Bookshop, next door to a restaurant where he ate, so that he could pick up the Communist publications Labour Monthly and Imprecorr. Party members noticed his interest and invited him to meetings. Meanwhile, he had met the novelist and screenwriter Guy Endore through an introduction from Alvah Bessie, one of the readers of the manuscript of The Water Wheel at Scribner’s. They started playing golf together almost every morning, during which Endore discoursed on the situation in Spain. Although Endore was already in the Communist Party, he oddly discouraged Sanford from taking the same step. But they continued to be good friends and later taught a course together on the modern novel at the People’s Educational Center, the Communist-led school in Los Angeles. Sanford eventually became a Party member and a very regular attendee at meetings; Roberts joined the Party to keep him company.

As a Marxist, Sanford was committed more emotionally than intellectually. He understood the Party’s version of Marxist principles, but he never read much Marx. He did not consider himself theoretically astute, and the manifestation of Marxist ideas in his fiction and nonfiction was mainly in the form of broad principles. Even these had a Populist and Romantic aura, to wit that “the rich are thieves and the poor are decent people.”16 His first two novels, while not conceived with political aims, expressed some sympathy for the underdog, a sentiment that first emerged during his boyhood experience when he had to defend a cousin who was always being picked on. His politicization was more evident in his third book, Seventy Times Seven (1939). In this novel, he interspersed in the text chapters expressing his view of American history. The narrative involves a farmer accused of murdering a wanderer, who tells the story of his hard life to the district attorney. While his strategy bears some resemblance to the technique used by John Dos Passos in U.S.A. (1936), Sanford was more directly influenced by William Carlos Williams’s In the American Grain (1925), which he had read nearly fifteen yeas earlier. To his surprise, when he found himself wanting to make historical judgments in the mid-Depression, he felt inspired by Williams’s passion.

In his 1943 antiracist classic, The People from Heaven (reprinted in 1996), Sanford created a Black woman driven to shoot a local white bully who has raped her in an upstate New York town. There is no evidence that this tale came from material beyond Sanford’s own imagination, how he believed oppressed people had the moral right to act, particularly when the rest of the community remains unmoved. The emotionalism of his narrative is underscored by his decision to publish the book despite the pleas of some of his Communist Party colleagues in Hollywood not to do so because they thought it would exacerbate racial tensions when wartime unity was required.17

Sanford’s stubbornness in such matters made him feel that his work was produced entirely without the impact or influence of the Communist Party but came instead exclusively from his own beliefs and sympathy. When he ignored advice from the Communist Party committee in Hollywood that had been established to help writers with their work, he was not further pressured by his comrades. However, he was not promoted as a Communist Party writer. He only contributed a single poem to the New Masses, although he served as an editor of the Clipper, a publication affiliated with the League of American Writers, to which he submitted a half-dozen pieces.

Eight years later, in the middle of the witch hunt, Sanford self-published a 400-page modernist, proletarian novel, A Man without Shoes (1951). This novel depicts the developing political consciousness of a working-class youth, Dan Johnson, and the events that finally lead him to volunteer to fight with the International Brigades in Spain. To some extent, Dan Johnson is John Sanford as he might have been with a different class background that could have brought about an earlier political awakening. Dan reacts resolutely to events such as World War I and the execution of Sacco and Vanzetti and to race and class oppression—to which Sanford was oblivious in his youth. Dan is not Jewish, although he apparently has no particular religious or ethnic background. But the touchstone at every stage in Dan’s political development is an awareness of anti-Black racism, and the main influences on Dan are two African American friends. One mirrors Sanford’s background: His name is Julian, he aims to become a lawyer, but he ends up writing novels. The other, Tudor Powell, called “Tootsie,” becomes Dan’s partner in a shoeshine business that they call the Black and White Polishing Company. Tootsie’s decision to go to Spain inspires Dan to follow him, thus recasting Sanford’s decision to follow Nathanael West to Hollywood. There is but one Jew in the novel, Seymour Wolf, who appears in a paragraph. Wolf is subjected in school to anti-Semitic harassment, which Sanford depicts as being similar to but not as intense as anti-Black racism.

In 1951, Sanford and Roberts were named as Communists by the screenwriter Martin Berkely and subpoenaed by HUAC. Sanford, still a Communist, invoked the Fifth Amendment, and Roberts, her brief Communist involvement years behind her, invoked the First Amendment. Sanford the Communist had already abandoned his screenwriting career and could not be hurt by blacklisting. Ironically, the former Party member Roberts was terminated by MGM and blacklisted until 1960, when she wrote the film True Grit, starring John Wayne.

Following a trip to Europe financed with Marguerite’s severance pay, the Sanfords had their passports confiscated and decided to reside in Montecito, near Santa Barbara, in 1955. Sanford had been attending Party meetings right up until the HUAC hearings. Then he stopped showing up at events and lost all contact with the organization when he traveled abroad and later moved to Montecito. Nevertheless, he considered it a matter of pride that he never actually resigned from the Party. His basic outlook was not particularly affected by the 1956 revelations of the Twentieth Congress of the Communist Party of the Soviet Union or the invasion of Hungary. For a few years he continued reading the People’s World, but then he decided to read only materials that interested him or were relevant to his work.

Throughout much of the 1950s, Sanford struggled with a writer’s block induced by a sense of guilt for being responsible for the destruction of Roberts’s career. He simply could not get any words down on paper and was possessed by a sense that he was punishing himself. By 1947–48 he had already finished The Land That Touches Mine, about the disintegration of an army deserter; it was published first in England and then brought out by Doubleday in 1953. Another novel did not appear until Every Island Fled Away (1965), about a California minister who defends a draft resister.

In 1967 Sanford published his eighth and last work of fiction. The $300 Man treated the relationship between a man whose wealthy father had bought his way out of the military draft and the man who served in his place. Sanford then changed his literary interests and published four volumes of interpretative political commentary on U.S. history. The first, A More Goodly Country, was rejected by all of the eighty or so publishing houses that agreed to read it, but it was finally published to critical acclaim in 1975. It was followed by View from the Wilderness (1977), To Feed Their Hopes (1980), and The Winters of That Country (1984). Next he published a multivolume autobiography using an experimental, hybrid technique utilizing screenplays, prose poems, and a realist narrative. The overall rubric was called Scenes from the Life of an American Jew. The first volume appeared in 1985 as The Color of the Air. Four superb sequels were published over the next few years, along with four more that are semirelated spin-offs. His autobiographical strategy uses a blend of narrative and documentary forms. In a sequence of scenes, what Sanford and others said is recalled and dramatized, and letters and book reviews are reproduced verbatim. Many episodes were reconstructed with the assistance of Roberts’s marvelous memory, and Sanford read the text to her as the work was in progress, believing that the quality of her listening drew from him a synthesis of perspectives that transformed his revisions.

Scenes from the Life of an American Jew covers many of the same years as A Man without Shoes; but in the latter most of the characters are Jewish, and there are hardly any African Americans. There is a dramatic polarity between Sanford’s middle-class life experience and the imagined one of Dan Johnson. The central Black protagonists in Sanford’s early novels were essentially idealizations and surrogates who were presented to the readers as teachers, guideposts, and role models.

Another Jewish American radical writer who used imaginary African American experiences to reflect on her own life was Vera Caspary (1899–1989).18 Caspary was a notable popular writer of mysteries and romances whose political views were not known to her audience until she narrated a rather tame version of her 1930s Communist Party activities in her autobiography, The Secrets of Grown-Ups (1979). Earlier Caspary had fictionalized some of her experiences in a novel, The Rosecrest Cell (1967). Otherwise, her reputation was solely that of a skillful suspense writer who excelled at portraying characters under stress due to fear or as a consequence of a police investigation. The paradigmatic work of her career is Laura (1943), which features a police investigator who falls in love with a woman he believes to have been murdered. In Bedelia (1945), The Murder in the Stork Club (1946), Stranger Than Truth (1947), Thelma (1952), False Face (1954), Evvie (1954), The Husband (1957), and many other works, Caspary customarily employs multiple points of view and often presents a leading character dominated by a particular emotion.

In an earlier phase of her career, however, Caspary wrote novels with more visceral social themes. Her first novel, The White Girl (1929), is the story of a light-skinned southern African America woman who passes for white. Thicker Than Water (1932) is an “insider” narrative of the assimilation of a Jewish family as their Orthodoxy fades and materialism becomes dominant. The Dreamers (1975) traces the lives of three women from the late 1920s to the 1970s. Caspary also collaborated on writing plays with other Left writers, including Geraniums in My Window (1934) with Samuel Ornitz and an adaptation of Laura (1947) with George Sklar. Among her many screenplays, I Can Get It for You Wholesale (1951) was written in collaboration with Abraham Polonsky.

The use of race as a mirror is most apparent in The White Girl. The novel tells of a light-skinned African American who “passes” in Chicago and New York but commits suicide when the white man she loves rejects her after her dark-skinned brother accidentally shows up. In her 1979 autobiography, The Secrets of Grown-Ups, Caspary traced the origins of this novel to the day she read a newspaper article about a Black woman passing for white. Caspary was suddenly overcome with guilt and shame because she remembered a light-skinned African American girl in her high school class who apparently shunned both Blacks and whites. Although Caspary was fascinated by the woman’s beauty, she could never bring herself to approach her and wondered why she shunned both races. Caspary explained: “So she became the heroine of my story. Our experiences and characters were woven together. I knew her loneliness, her fears, hopes and shame; she shared my early jobs. I endured the snubs and insults of white people who believed themselves superior. When I walked on a crowded street or rode on the subway I was a black girl passing as white. She suffered and rejoiced as I had in love. I shed her childhood tears.”19 Caspary discussed how she acquired additional material from an African American male friend who had a cousin who passed for white.

Her memoir does not address the impossibility of her becoming the Black woman passing as white or that the blending of the two—herself, whom she knew very well, and the girl she hardly knew—created something quite different, a third person. This omission reinforces the impression that the story of the beautiful Black woman passing as white is also the story of Caspary’s own experiences as a Sephardic Jew negotiating her own ethnicity.20

Another variant of the connection between Jewish identity and the mirror of race arises in the account that the Jewish historical novelist Howard Fast provides in his 1990 autobiography Being Red. It concerns his 1944 novel Freedom Road, the story of a Black southerner, Gideon Jackson, during Reconstruction. While Fast conducted extensive research on the post–Civil War era, he lived for a while in the southern mansion belonging to the old aristocratic family of the wife of his publisher. Concealing his Jewish identity from them, Fast listened to their stories and was amazed at the ease with which “cultured” people could hold such blatant prejudices. He studied their attitudes and examined the artifacts in their museumlike house.

What had originally prompted Fast to write this novel was the combination of four events that paired anti-Semitism and anti-Black racism. First, during his youth he had hoboed through the South and had been appalled by the racism he witnessed. Second, Fast and his wife had spent an afternoon with the novelist Sinclair Lewis and had been horrified to find him expressing “genteel antisemitism.” Third, while working at the Office of War Information during World War II, Fast had initiated a project to study the possibility of integrating Blacks into the segregated army. Finally, as Fast recalled, “Reports were beginning to filter out of Germany about the destruction of the Jews. . . . [Hence] all the notes and thinking that I had done for a novel about Reconstruction came together—and every moment I could steal from my work at the OWI was put to writing the new book.”21

Thus Fast’s correlation of anti-Semitism, in both genteel and vulgar forms, with anti-Black racism on the part of rich and poor compelled him to write his first novel with Black central characters. Freedom Road went on to become a literary sensation worldwide; there are claims that it was the most widely printed and read book of the twentieth century. W. E. B. Du Bois wrote a foreword praising its psychological insight into African Americans, and Paul Robeson offered to play Gideon Jackson in a Hollywood film version. However, the proposed film was never made as both Fast and Robeson were soon blacklisted in Hollywood.22

FASCINATING FASCISM

During World War II, the menace of German fascism was an obsessive theme of writers with pro-Communist backgrounds, many of whom were Jewish. Their novels began to emerge in 1946, and most authors were combat veterans or war correspondents. Few would endorse the point of view of The Cross and the Arrow. Albert Maltz’s novel suggested that Germans were potentially normal citizens of the West, capable of decency but violently deformed by a monstrously indecent ideology and social system. Moreover, Maltz held that, while far more extensive, Nazism was nevertheless a continuation of other barbaric episodes in history.23 To the contrary, Martin Abzug’s Spearhead (1946), Stefan Heym’s The Crusaders (1948), and Irwin Shaw’s The Young Lions dramatized the argument that Nazi evil was sui generis. No Left novelist would admit to Vansittartism, but such a view is insinuated in these three novels principally by the displacement of a German penchant for militarism by an inordinate degree of anti-Semitism. This argument reached a climax in The Wine of Astonishment (1948), by Martha Gellhorn (1908–98), a Communist fellow traveler at the time of the Spanish Civil War. Her novel, which tracks the adventures of a Jewish GI in the last days of World War II, is close to a call for random retaliation against German civilians.

Spearhead was the first novel of Martin Abzug (1916–86). Abzug was born in New York City. He worked in his family’s garment business from 1934 to 1960 before becoming a stockbroker. As a young writer in the late 1940s, he was associated with the Communist political and cultural movements. In 1944 he married a radical lawyer from the same milieu, Bella Savitzsky (later better known as the congresswoman Bella Abzug).24Spearhead reflected Abzug’s military service and described the retreat of a U.S. Army artillery unit during the early days of the Battle of the Bulge. The plot centers on the tension between two of the unit’s officers. Lieutenant Knupfer is a worldly German refugee who considers the peculiar German mentality as beyond redemption, while Captain Hollis believes that Germans are just ordinary people who had received a rotten deal. Antagonism initially erupts between the two over the taking of German prisoners. Knupfer insists, “You should have shot them instead. . . . They can’t be changed—that much I know. A dead fanatic is better than a live one.” Hollis replies, “They didn’t act fanatic, Knupfer. They acted like you and I would have acted; they were scared and they gave up.”25

Knupfer is convinced that the U.S. Army is incapable of fathoming the depth of German depravity; he fears that the United States will leave Europe too quickly after the war, and the task of cleansing will remain unfinished. The strain between the two men and their rival philosophies erupts again when a captured German prisoner, Wunderlich, cries out to alert his fellow soldiers that U.S. troops are nearby. Knupfer attempts to silence Wunderlich by strangling him, but he is stopped by Hollis, who insists that “we don’t kill prisoners in cold blood.”26 As the novel moves toward its calamitous climax, Wunderlich manages to seize a pistol during the chaos of an attack and fatally shoots Knupfer. When Hollis finds out what has happened, he beats Wunderlich to death.

Stefan Heym’s The Crusaders commences with a corresponding polarization of U.S. Army soldiers. Sergeant Bing, another German refugee, albeit Jewish, reacts to the taking of German prisoners of war in a manner similar to Lieutenant Knupfer’s: “I hate ’em.” Lieutenant Yates, formerly an assistant professor of German at a midwestern university, protests that “this is a scientific war” and offers a rationale for the humane treatment of German prisoners: “The man over there’s been doing the same thing you’ve been forced to do: He’s followed orders. . . . He’s the victim of his politicians as we’re the victim of ours.”27

Other themes in The Crusaders are comparable to those encountered in Abzug’s and Shaw’s novels, notably the opinion that U.S. soldiers have never been educated about the democratic and antiracist goals of the war, and that the military defeat of Germany will not necessarily mean de-Nazification unless extreme measures are taken after the war’s end. Moreover, Heym’s treatment of the early postwar occupation period suggests that the United States is only interested in promoting an order where capitalism can flourish. General Farrish, whose behavior suggests General George S. Patton’s, aims to create an efficient postwar administration by employing former Nazis.

Heym (1913–2001) was born Helmut Flieg into a Jewish family in Germany. Drawn to Marxism in his youth, he aspired to become a journalist and entered Humboldt University in Berlin in 1932.28 In March 1933, following Hitler’s ascendancy to power, Heym was forced to flee Germany at age nineteen; his father, after being held hostage, committed suicide. In Czechoslovakia Flieg adopted the name Stefan Heym, continuing as a journalist but also writing poetry, literary criticism, and drama. In 1935 Heym received a scholarship from the Jewish American academic fraternity Phi Sigma Delta, which was established to allow German Jewish students to continue their education.

Heym soon came to the University of Chicago to study German literature, but he also began publishing in German-language journals as well as in the Nation magazine in 1936. He received a B.A. and then an M.A. degree from the University of Chicago, with a thesis on the German poet Heinrich Heine. Sympathetic to Communism and fiercely anti-Nazi, Heym moved to New York to edit the pro-Communist German-language Das deutsche Volksecho until 1939. He later indicated that he had been a member of the Communist Party from 1936 onward. Subsequently he worked as a salesman for a printing company.

By 1942 Heym had published his first novel, Hostages, about life under the Nazis; it became an instant best seller. At that time he legally changed his name to Heym and fell in love with Gertrude Gelbin, a widow twelve years older than himself; they were married the following year. Likewise a member of the Communist Party, Gelbin was employed by MGM and, under the name Valerie Stone, published children’s stories and articles on subjects of interest to women.

Heym joined the U.S. Army in 1943 and was trained in military intelligence. In 1944 he published Of Smiling Peace, a failure as a work of literature, although it portends the more ambitious The Crusaders. Based on research, the novel is set in North Africa (where Heym had never been) and uses the problems of an emancipated colonial state to consider the motivation for the war and the nature of the fascist cast of mind. In June 1944 Heym landed in Normandy just after D-day and spent the rest of the war close to the front lines. His work involved interrogating prisoners, writing leaflets, broadcasting using loudspeakers to enemy positions, and especially writing radio programs as part of a Mobile Radio Broadcasting unit. Since his unit was near to the front, there was often the danger of attack and capture, and Heym was awarded a Bronze Star for bravery. After the war Heym spent three years working on The Crusaders, which he cut down to 300,000 words from a much longer manuscript. The novel went through four printings in the first three weeks of publication, and eventually 2 million copies were sold in English and other languages.

The Crusaders differs from Spearhead and more closely resembles The Young Lions in that a Jewish soldier is killed and the naive liberal, Yates, eventually forms a mature understanding of the nature of the evil he must face. The Crusaders also resembles The Young Lions in that anti-Semitism in the U.S. Army is emphasized and Nazism is depicted as an all-encompassing corrupt force. The hard-bitten Sergeant Bing is taken aback and descends into a deep depression when he visits the German city where he had been born and raised, only to find its citizens thoroughly depraved by fascism. Where Heym differs from both Abzug and Shaw is in his placing a strong emphasis on the fascistlike behavior of U.S. officers, who make common cause with the Nazis to gain economic profit.29 Like Spearhead and The Young Lions, however, The Crusaders admonishes the reader—to wake up, to develop a new consciousness, and to finish the sanguinary job of eradicating German fascism at its vile roots.

By the start of the next decade, the novels by Jewish pro-Communists had become less vituperative and waxed nostalgic for the fraternity of men who had worked together to save democracy. The Sun Is Silent (1951), by Saul Levitt (1911–77), traces the journey of a group of men from their army air force training through the completion of their bombing raids over Europe.30 Levitt had served as a radioman-gunner on a B-17, and his novel was especially effective in dramatizing the elements of a bombing mission—the alert, the briefing, the takeoff, enemy fighter attempts at interceptions, the bomb run, and the return flight. Moreover, although his novel has a collective protagonist, Levitt managed to infuse members of the bomber crew with distinctive personalities.

Levitt was born in Hartford, Connecticut, and attended the City College of New York. A close friend of the Communist writer Arnold Manoff (1914–65), Levitt was a pro-Communist in the 1930s and published in the Anvil, the New Masses, and the International Publisher’s collection Get Organized! (1939). During World War II he was a correspondent for Yank while serving in the air force, and he continued to write literary reviews and political commentary for the Communist press as Alfred Goldsmith. In the 1950s he was one of the writers for the television programs Danger, You Are There, Wide Wide World, Climax, and other shows while publishing short stories in Harper’s, Atlantic Monthly, American Mercury, Fortune, and the Nation. In 1959 he produced a two-act play about an incident from the Civil War called The Andersonville Trial, which was rewritten and expanded to achieve acclaim as an Emmy Award winner in 1971. In 1971 he also produced The Trial of the Catonsville Nine, a play based on the trial of the pacifist Berrigan brothers.

Face of a Hero (1950) by Louis Falstein (1909–96) is noteworthy for its modest portrayal of an ordinary man who performs his duties as a committed antifascist. Falstein was born in the Ukraine and came to the United States at age sixteen.31 His father had orchards in the Ukraine, but he became a businessman in the United States. The family had no interest in either radical politics or Zionism, and Falstein lacked direction as an adolescent. He was forced to go to Hebrew school but found it dull. He attended but did not graduate from high school in Chicago, although he later secured a diploma by taking a special course. During the early Depression he found work for a while as a shoe salesman, but he was mainly unemployed. In 1934 he came to Detroit to seek work in the auto plants. At this time he was drawn to the John Reed Club, where he became friends with the African American poet Robert Hayden and developed an admiration for the radical attorney Maurice Sugar. Occasionally he wrote skits for fund-raising events. His name appeared (as Lewis Fall) as one of the editors of the Detroit Left publication New Voices, but he published nothing. After changing his name for a while to Fallon, because of the Ford Motor Company’s reputation as being anti-Semitic, he at

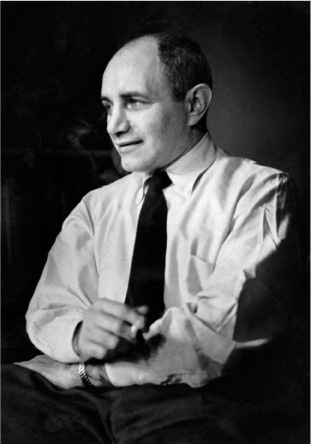

During the 1930s and 1940s, SAUL LEVITT published fiction widely under his own name and wrote criticism for the New Masses as Alfred Goldsmith. After World War II he published a novel and achieved success as a playwright. (Courtesy of Howard Gotlieb Archival Research Center at Boston University)

last found work. But when a union leaflet was discovered in his lunch bucket, he was fired and was forced to apply for “pick and shovel” work with the WPA. To his good fortune, he secured a job with the Federal Writers Project.

At the WPA Falstein found himself under attack by the Black Legion, a neofascist organization that denounced him and other radicals as Red spies and threatened their lives. Falstein recalled that he was referred to in the newspapers as an “agent of the Third International.” Shortly afterward a coworker on the Federal Writers Project was murdered. In order to help save the WPA from elimination, Falstein joined the Save Our Jobs March in Washington, D.C., spending a week living in a tent in Potomac Park and lobbying congressmen. At this time, Falstein became obsessed with the Spanish Civil War. He generally felt like an unheroic, perhaps even cowardly person, but the logic of his political views made him susceptible to pressure to take action on behalf of the Spanish Republic.

When two of his friends joined the Abraham Lincoln Brigade and were killed in battle, Falstein volunteered. Before he could depart, however, he received a court order to appear as a witness at the impending trial of the members of the Black Legion. This was an event that attracted worldwide attention. Legion “executioners” paraded before a crowded courtroom and bragged about their exploits in killing scores of persons—sometimes by burying them alive in lime pits—because they were African American or “Red unionists.” When the trial was over, Falstein found work at a General Motors plant, only a week before the famous sit-down strike began. He remained in his plant for six weeks. He was often frightened by the efforts of the police and vigilantes to evict the strikers, but he drew strength from his sense of solidarity with other men and women in the battle.

Just before the start of World War II he moved to New York. As a Communist he believed that he should participate in the war, even though he felt fearful and unsuited. To his amazement he was accepted for combat duty in the army air force and managed to fly fifty bombing missions from 1943 to 1945, receiving a Purple Heart and Air Medal with three clusters for his service. Face of a Hero was written to show that even a man with as little self-confidence as he had could survive and carry out his duties.

In the process of writing the novel, he discovered how easily he could put words together. The book’s sudden best-seller status in the United States, along with its success in Britain, bolstered his ambitions. In the postwar period the New Republic published everything Falstein submitted. Politically, he remained outside the Party membership but was more loyal to the Party than ever. He faithfully read the Daily Worker and the New Masses and its successors. Through the dancer and poet Edith Siegal he met Michael Gold, and he knew Len Zinberg as well. He believed that Stalin could do no wrong and was unaffected by the revelations

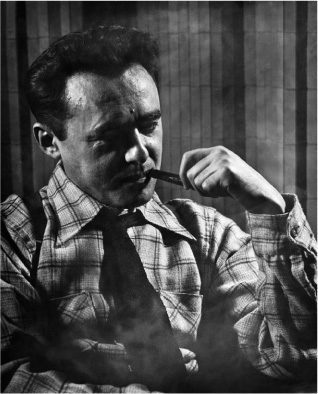

LOUIS FALSTEIN, a pro-Communist from the 1930s until the end of his life, wrote a popular novel about World War II. (Courtesy of Louis Falstein)

at the Twentieth Congress in 1956, and he continued to read and study Marx in his spare time. His wife worked as a guidance counselor, and in 1946–48 he took courses at New York University, after which he taught writing there in 1949–50 and at City College in 1956.

Falstein’s forte was writing popular literature. He greatly admired Harold Robbins’s A Stone for Danny Fisher (1952), and in 1953 he published his own urban crime novel, Slaughter Street, billed on the cover as “a savage novel of crime and lust in the big city.” In 1954 he published a thriller, Sole Survivor, about a concentration camp survivor who encounters his Nazi tormentor in New York. In 1965 he published a memoir of his family in Europe, Laughter on a Weekday, and in 1968 he wrote a biography of Sholem Aleichem. His last, unfinished work was an autobiographical novel based on his experiences with the WPA in Detroit.

FROM EMILY DICKINSON TO EMMA LAZARUS

If the Jewish cultural Left was literarily involved in a group of pro-Communist publications, it was the individuals who kept those publications afloat who gave the tradition its unique stamp. One of the most pivotal was Morris U. Schappes (1905–2004), who was born Morris Schappeslevetch in the Ukraine, although his family was already living in Brazil.32 His father, an illiterate but skilled anarchist worker, had gone there in search of employment. Schappes came to New York in 1914 speaking Portuguese, Spanish, and Yiddish. A brilliant student at Public School No. 64, he skipped grades five times and was sent to a special high school on the City College campus where he completed a four-year curriculum in three years, during which time he developed a stuttering problem. After graduating from City College, he attended graduate school at Columbia University and received an M.A. in 1930. He commenced work on a dissertation on Emily Dickinson’s poetry and joined a Marxist study circle whose participants analyzed the socialist classics “not just line by line, but comma by comma.”33 In 1932 his academic work encountered a crisis. Schappes had been the first to discover that Emily Dickinson’s family had modified her unpublished poems. After he published his findings in American Literature, the Dickinson estate broke off all relations with him.34 He concluded that to continue working on his doctorate would mean starting over with a new dissertation topic. Accordingly he turned his energies to teaching, writing, and left-wing activities. During the early 1930s, he published a great deal in the literary pages of the New York Post. He also wrote an essay for Modern Monthly in 1933 on T. S. Eliot’s anti-Semitism, and he contributed to Poetry and the Symposium.

By 1932 academics were for the first time becoming attracted to the Communist Party, especially through the activities of the League of Professionals for Foster

MORRIS U. SCHAPPES was a popular English teacher at City College of New York who joined the Communist Party. He was blacklisted after serving a prison sentence and became a prominent editor and authority on Jewish American life. (Photo by Nell Greenfield; courtesy of Morris U. Schappes)

and Ford and later the Pen and Hammer, a small group with a headquarters on Sixteenth Street that was similar to the John Reed Club but with a less visible Party presence. The Pen and Hammer was comprised primarily of scholars who were literary critics, historians, and social scientists, but it also included a few physical scientists. Schappes, who was already teaching at City College, joined the Pen and Hammer in 1931 and a year later became its national executive officer. For the Pen and Hammer magazine, he used the name Vetch, which was the last part of Schappeslevetch. The only active branch of the Pen and Hammer was in New York, although there were individual correspondents around the country. The Pen and Hammer fell apart in the period leading up to the Popular Front.

In 1934 V. J. Jerome signed Schappes’s application to the Communist Party, wherein he enrolled under the name Alan Horton. What convinced Shappes to join was an incident in which the Communist Party members active in the Pen and Hammer took what he believed to be the wrong side in a dispute. He met with Party leader Earl Browder to complain. Browder agreed with Schappes, who concluded that the best way to influence Party policy was from the inside. Since there did not yet exist any units for Party academics, Schappes joined a branch of industrial workers and became its educational director.

By 1936 Schappes had taught at City College for eight years without gaining tenure, which was at the time a prerogative of full professors and a status conveyed by the president. In April 1937 the English Department chairman happened to walk into his class and heard Schappes reading from the work of Percy Bysshe Shelley, which he mistook for a writing by Marx. Soon thereafter, Schappes received a notice that he would not be reappointed in the fall. Within a short time protests came from unions all around the country, and hundreds of students staged a sit-in.35 When Schappes was reappointed, further left-wing activity was galvanized on the campus.

The first Communist Party unit at City College had been connected with the Harlem section of the Party because of the college’s location. The three founding members began recruiting around issues of tenure, working conditions, and the need to combat fascism, for which they set up the Anti-Fascist Association of Staff of City College. In 1934 separate units had been established at the Brooklyn branch of City College, Hunter, and Queens College. The Communist publication Teacher-Worker was an eight-page printed bulletin issued anonymously, and Schappes was among the editors. The publication was distributed through the college’s mailroom. The Communist Party’s influence was so great in the Instructional Staff Association that the Party members had a policy of deliberately maintaining a majority of non-Communists on the association’s executive committee; the Party members thought that it was better to lead, and sometimes be outvoted, than to merely dominate the organization. Through the efforts of Party members, a more democratic tenure system was proposed, and strong ties with the labor movement were created.

As a result of his encounters with anti-Semitism at City College, Schappes experienced his first sense of his connections to Jewishness. There were anti-Semites on the college faculty, and a German professor was accused of anti-Semitic behavior. After a brief period of doing research on the English poet Christina Rossetti (1830–94), Schappes found himself captivated by the Jewish New York poet Emma Lazarus (1849–87). His fascination with women poets seemed to be connected with the education on “the Woman Question” that he had received in Communist circles. The Communist orientation did not address sexual issues; it was primarily aimed at securing the rights of women in trade unions. It also had a goal of electing women to leadership positions in local Party units and state committees. Schappes discovered that nothing of significance had been published about Lazarus since the early 1900s; scarcely more than one of her sonnets was known to the public. Since he had become active in the Communistled Jewish People’s Fraternal Order, Schappes applied for and received $100 to subsidize his research on Lazarus.

Schappes’s scholarship and political activism went hand in hand. In 1938 the Anti-Fascist Association of City College persuaded the administration to call a collegewide antifascist meeting. Schappes was chosen to speak for the faculty, and 3,000 students attended the assembly. This was a time of great influence by and prestige for the Party, but much of it evaporated at news of the Hitler-Stalin Pact. Then, while the Party was at its weakest and most isolated, the Rapp-Coudert investigation of subversives in the New York state school system began.36

Schappes had used a Party name and published anonymously to protect his job, but he nonetheless sold the Daily Worker on campus. Faculty, students, and staff knew that he was a Party member. He was investigated and faced the dilemma of lying about his Party membership or admitting it at the cost of his job. Schappes lied, claiming that he had left the Party a year earlier and that all the members he had known had vanished from the scene. He was then tried for perjury. While he was out on bail, he completed his project on Lazarus. At the New York Public Library he was befriended by Joshua Bloch, who had been chief of Jewish acquisitions for thirty years. Bloch made available to Schappes unpublished writings of Lazarus and introduced him to the New York Public Library Bulletin, in which Schappes published a group of Lazarus letters.37 The library’s board of trustees was upset by this, but Bloch vouched for Schappes, telling them that he was a first-rate scholar.

While serving his prison sentence for perjury in the Tombs, Schappes began research on the history of Jews in the United States. Bloch arranged for publishers to send him books, which is the only way that prison authorities would allow him to receive them. In prison Schappes completed the major portion of his background reading on the topic and decided what he wanted to do. In 1944 he was paroled on condition of obtaining employment. A friend procured for him a job producing electronics in a war production plant. After he finished his parole, he began his history of the Jews in the United States in earnest. He also lectured on the topic for small fees. His lectures were from time to time sponsored by the International Workers Order, an organization that not only sold insurance but promoted a rich cultural life. His wife, Sonya, was a teacher but found that she had been blacklisted because she had refused to shed the Schappes name. She then began working for booksellers and reprint houses and for the Communist Party bookstore at the Party-led Jefferson School of Social Science. The two lived frugally and decided not to have children so that they could devote themselves fully to the revolutionary cause.

While in prison, Schappes had been offered a contract by the Alfred Knopf publishing house to write a history of Jewish Americans, but Schappes was hesitant to make a commitment at that time. His main interest was to do literary and scholarly work, and so far as he knew, no history of Jews in a particular country had been published by a Marxist anywhere in the world, not even in the USSR. But Schappes was concerned that it would seem like a retreat to emerge from prison and bury himself in writing a book, as if he had gotten scared and was dropping out of political activity. So he went to Earl Browder to ask for a political assignment from the Party to prepare the history. Browder, who was always sympathetic to scholarly and cultural work, gave him a written statement declaring that he was to be assigned to the Jewish history project full time. William Z. Foster, too, had a close relationship to Jewish workers, especially garment workers, and looked favorably on the effort. Schappes was forced to carry out most of his research by correspondence, but he found archivists quite willing to help him.

In 1938 the New York State Committee of the Communist Party had sponsored a publication called Jewish Life, which was an official Party organ. Schappes had been a member of the editorial board, along with Rabbi Moses Miller and Party leader Alexander Bittleman. The Communist Party financially supported and sponsored the magazine but did not promote it. Jewish Life lasted only sixteen months, collapsing after the Hitler-Stalin Pact. The Party then published Jewish Survey, which lasted a year and a half, followed by Currents, which appeared during World War II.

In October 1946 a new version of Jewish Life appeared, again led by Communists but without a specific Party connection. Unfortunately, at the same time an Orthodox Jewish magazine with the identical name appeared. In the early 1950s, when the Communist editors of Jewish Life were called before investigating committees, the editors of the Orthodox magazine became fearful of being identified with alleged subversives. Consequently its publisher approached the district attorney and charged the pro-Communist Jewish Life with a copyright violation. In 1958 Schappes and the other editors were forced to put several notices in the magazine explaining that the two publications were unrelated. The name of the Communist periodical was changed to Jewish Currents at the beginning of the next year.

In the late 1940s Schappes began to realize that his thinking about Jews had evolved dramatically. At first he held views akin to an assimilationist indifference about Jewish culture. Then, provoked by Hitler, he became concerned with anti-Semitism. He now realized that he had developed a genuine fascination with Jewish affairs. Previously his main association with Jewish culture had been through his parents. He had eaten with them once a week until he was married. However, instead of using the visits to improve his Yiddish, he had tried to get his mother to upgrade her English. But after the battles against anti-Semitism on the City College campus, Schappes began to frequently interrogate his parents about their own experiences. Schappes’s father died while Morris was in prison, but after his release he visited his mother and sister regularly to ask them about their Jewish experiences.

Throughout the Cold War Schappes rendered his services to Jewish Life and to Jewish Currents on a voluntary basis. His wife continued to support him, although he had a small income from lectures and some of his publications. The magazine was published in the offices of the Party’s Yiddish-language paper, Freiheit, so there was no phone bill, rent, or printing costs. In the early 1950s, when the Party began sending a section of its leadership underground, the magazine moved to Union Square due to fear that there might be a police raid on the old building and the subscriber list would be confiscated. The new space had been previously occupied by the Jewish Labor Committee, which had been created by Communist Party member and union leader Ben Gold during World War II. Although the committee had folded, its furniture remained, and Jewish Life took possession of it.

Working on his book on Jewish American history and putting out the magazine were Schappes’s major political responsibilities, but he also taught at the Communist Party’s training school. Originally, he had taught the theory of “the Negro Question” until the Black Party leader Doxey Wilkerson produced a study arguing that the Black Belt region in the South had shrunk to a point where Marxists could no longer refer to it as a nation. The Black Belt nation had been the basis of the Party’s theory and program relating to African Americans. Schappes supported Wilkerson, and they became a minority opposed to the Party’s traditional view. Accordingly, they were both switched to teaching other topics. Schappes began to specialize in propaganda techniques and “the Jewish Question.” For him, like other Jewish Communist cultural workers, the topic of anti-Black racism was a major issue of concern. But his politics had formed first through developing an internationalist identity and then by turning to Jewish history and culture within an internationalist framework.

From the time that Jewish Life began, it had followed Party orthodoxy, such as supporting the expulsion of Earl Browder and ignoring the implications of the infamous Doctors’ Plot in the Soviet Union in 1952. The magazine’s policy, being so adamantly pro-USSR, had the effect of allowing Schappes greater flexibility in his other relations with the Party. When the Party leader Bob Thompson lambasted Schappes’s old friend Bill Lawrence (a pseudonym for William Lazar) at a Party convention, Schappes felt he could protest the attack with impunity. Likewise, Schappes violated the Party injunction not to recognize expelled members by continuing to talk to Bella Dodd, the onetime leader of the Communist teachers. But the connection between orthodoxy and privilege was not discerned. The editor Louis Harap defended the 1952 Prague trials in Eastern Europe not because he believed that this would give him wider latitude in other arenas but because he sincerely believed the charges. Later, Schappes and Harap came to see themselves as having been like horses wearing self-imposed blinders; they could not see the crimes of Stalin and the other Soviet leaders, and they confidently dismissed criticisms of Stalin and the others because they believed that the sources of such criticism were contaminated. Within such a framework, they imagined themselves to be absolutely honest and consistent. The premise that the Soviet leadership was benign had to be accepted if one were to be part of a wonderful movement for a better world.

However, there were certainly moments of intellectual grappling and questioning. When friends of Schappes returned from World War II and told stories about Russian soldiers misbehaving and expressing anti-Semitic views, the Jewish Currents editors could neither believe nor entirely disbelieve the stories. Consequently, they attributed the stories to the fact that U.S. troops had entered the war late and that the Soviet troops were the recently drafted, backward peasant elements.