The United States

The story of brewing and beer culture in most nations around the world is deeply rooted in, and affected by, an old and established tradition that continues to exert its influence today. In the United States, on the other hand, we find a situation where tradition was interrupted, suspended for a dozen years, effectively discarded for half a century, then completely reinvented. Since the final two decades of the twentieth century, American brewing and beer culture has been driven by brewers who approached a clean slate with single-minded determination, motivated by their own creativity, a near obsession with innovation, and a consumer base eagerly awaiting the myriad of fascinating new beer brands that are introduced each year.

Pitching Miller Lite to Chicago White Sox fans at US Cellular Field (formerly New Comiskey Park). A bottle of beer in the stands is an integral part of enjoying America’s “National Pastime.” Miller Lite, first test-marketed in 1973 was the pioneer brand in the reduced-calorie market segment in the United States. (SABMiller/One Red Eye/David Parry)

By the second decade of the twenty-first century, there were more than 2,500 hundred breweries in the United States, a 50-fold increase from 1980. One of this author’s greatest regrets in doing this book is that it is impossible to mention, much less describe in detail, more than a fraction of these. For every one that is described, there are many more who are worthy of mention, and worthy of celebration.

The history of brewing in the United States began with indigenous people, especially in the Southwest, but most of our familiar traditions arrived with the European immigrants. The English brought their top-fermenting ale yeasts with them and immediately established breweries in the Colonies. By the time of the American Revolution, ales and porters were well developed as part of daily life, and most landowners were as likely to have a brewhouse on their grounds as a stable. Among America’s early statesmen, not only Samuel Adams, but both George Washington and Thomas Jefferson were brewers.

Next, around 1840, the first wave of German immigrants introduced bottom-fermenting yeast to American brewing, and the United States soon became a land of lager drinkers.

In 1873, there were 4,131 breweries spread across nearly every small town and city neighborhood, each with its own special style of beer. The idea of a town or neighborhood brewer was as common as the town baker or neighborhood butcher. The advent of a continental railroad network and the invention of ice-making machines made possible the rise of megabrewers like Schlitz, Pabst, and Anheuser-Busch, who became large regional brewers. By World War II were in a position to launch truly national brands.

Enjoying beer, music and camaraderie in a painting by John Gannam. It was part of the 1950s “Home Life in America” series used in advertising by the United States Brewers Foundation in a campaign promoting “America’s Beverage of Moderation.” (Author’s collection)

In the twentieth century, things changed as nowhere else on earth except for parts of Canada and Scandinavia. Beer simply vanished from the tables of most Americans, and a great industry sputtered to a halt. The temperance movement led to the Eighteenth Amendment of 1920, which instituted Prohibition, a misguided experiment which decimated an industry and gave rise to organized crime on a heretofore unseen scale. When the curtain of darkness was finally lifted in 1933, only 756 breweries reopened, and many of these failed during the Great Depression. The rise of national brands, with their multi-site industrial-scale breweries, defined the landscape of an industry. Small local and regional brewers could not compete and many disappeared. By 1965, fewer than 200 breweries remained in the United States, and only 15 years later the number of brewing companies had fallen below 50. Meanwhile, the volume of beer produced by the national brands made the United States the largest brewing nation in the world for over half a century. From 105 million hectoliters in 1959, the industry doubled to over 200 million (170 million barrels) by 1979. The corresponding figures for second-place Germany in those years were 46 and 94 million hectoliters.

The Schaefer Brewery of Brooklyn was one of America’s five largest in 1948. (Library of Congress)

The recent chronicle of American brewing is a tale of two industries. There is a twentieth-century story of mega-brewers that rose to dominate an industry and rank among the biggest in the world, and a twenty-first-century story of the mushrooming interest in craft brewing by a consuming public interested in artisanal products and in distinctive, innovative cuisine choices. Recent trends in American brewing include higher ABV and higher hop content, including not only a proliferation of IPAs but double IPAs as well. Many American brewers are now barrel aging many of their beers in oak, and it is not uncommon to see unpressurized cask ale offered at brewpubs and specialty beer bars.

Serving Hamm’s, brewed in St. Paul, at a typical backyard barbecue, circa the 1950s. Hamm’s was once a major regional brand. (Author’s collection)

Brewery restaurants, with fuller menus than the average brewpubs, were pioneered by brewer Dan Gordon and chef Dean Biersch, who started their first in Palo Alto, California in 1988. Even as the concept proliferated among other restaurateurs, Gordon Biersch evolved into a multistate operation. Gordon Biersch was later sold to CraftWorks, which also owns the Rock Bottom brewery restaurant chain. Another, similar organization is the BJ's Restaurant & Brewery chain. Dan Gordon still operates a Gordon Biersch production brewery in San Jose, California. Numerous independent brewery restaurants, cropping up all the time, continue to operate nationwide.

Pouring a beer for dad. (Library of Congress)

Looking forward into the twenty-first century, the chronicle centers on the tale of a craft brewing segment that is growing by double digits annually, and, more important than that, it is controlling the narrative, not only in leading business journals, but among consumers—from the beer traveler visiting America to the “foodie” beer connoisseurs at home. Such people enthuse about beers such as Anchor Steam, Dogfish Head 90 Minute IPA, or Stone Brewing’s Arrogant Bastard, not the flavor-neutral adjunct lagers stacked in supermarket aisles.

One of Milwaukee’s greatest names, Schlitz was one of America’s “Big Three” for most of the twentieth century. The “cone top” can was introduced in 1935. (Author’s collection)

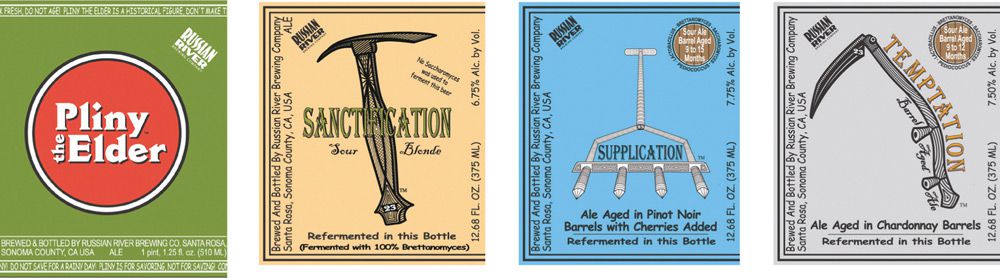

The story now is of brewing companies that were unknown in the 1990s when Anheuser-Busch last brewed more than 100 million barrels annually. Looking at the beers and breweries rated most highly by entities such as Beer Advocate and RateBeer, one sees names such as The Alchemist, AleSmith, Bells, Cigar City, Hill Farmstead, Founders Brewing, Three Floyds, and Toppling Goliath. These names may—or may not—change and be superseded in the pantheon by other names, but this will only speak to the vibrancy of the American craft brewing industry. One name, that of the Russian River Brewing Company, reminds us of their signature beers, Pliny the Elder and the rare Pliny the Younger, which consistently vie with Westvleteren 12 on the lips of consumers as they sip and designate the best beers in the world.

The Redhook Ale Brewery, founded in Seattle in 1981 by Paul Shipman and Gordon Bowker, was a pioneer microbrewery that did well. (Author’s collection)

Looking back before the turn of the century, Anheuser-Busch, the industry leader for half a century, controlled 53 percent of the market, and Miller Brewing had a 23 percent market share, with both companies brewing at many sites around the United States. Rounding out the Big Three was Adolph Coors of Golden, Colorado, controlling 13 percent of the market from the largest single brewery in the world. Within a decade of the turn of the century, they still maintain a volume lead, but their overall numbers are slipping, and their flagship brands are down by double-digit percentages. Furthermore, none of the Big Three is still American-owned. Anheuser-Busch was acquired by Belgian-Brazilian InBev, Miller was acquired by London-based South African Breweries, while Coors is the second name in a consortium in which the first name is that of Canada’s Molson.

Classic labels from well-known names of first generation microbreweries which are no longer with us. They include New York City’s Manhattan Brewing; Montana Beverages of Helena, known for reviving the Kessler brand; Catamount Brewing of White River Junction, Vermont; and Allan Paul’s much missed San Francisco Brewing, that city’s first brewpub. (Author’s collection)

To complicate the layman’s understanding of the corporate structures of Miller and Coors, the United States operations of these two entities formed a joined marketing company called MillerCoors in 2007, intended to share a common sales apparatus in the United States market.

Today, the lead brands of the Big Three still dominate the market. The top two in the United States, and the top brands behind China’s Snow worldwide, are Bud Light and Budweiser from Anheuser-Busch. In the next tier are Miller Lite and Coors Light as well Anheuser-Busch budget brands such as Natural Light, Busch, Busch Light, and Michelob, the latter once positioned as the Anheuser-Busch premium brand. Miller High Life and Miller Genuine Draft are at the bottom of the top ten, while the onetime flagship Coors (aka Coors Banquet Beer) brand is at the bottom of the top 25. All of them are “adjunct lagers,” meaning that they are brewed with rice and corn as well as barley malt, and they range between 4 and 5 percent ABV.

Fritz Maytag saved San Francisco’s Anchor Brewing from extinction, and became the indispensable role model for the craft brewing movement. (Anchor)

Another company included among the twentieth-century megabrewers is Pabst Brewing. Founded in Milwaukee, America’s one-time brewing capital, in 1844 by Jacob Best, and taken over by Captain Frederick Pabst in 1889, Pabst was one of the largest three or four brewing companies in the country for about a century with its flagship lager, Pabst Blue Ribbon. In 1985, Pabst was acquired in a hostile takeover by the enigmatic recluse Paul Kalmanowitz, who began closing breweries and selling assets. As Pabst declined, it became a holding company of bygone brands, buying the fading legacy names of defunct companies such as Heileman, Lone Star, Pearl, Olympia Brewing, Primo, Rainier, Schaefer, Stroh, and Schlitz, which for many years was, itself, one of the biggest three or four. Since 1996, Pabst has not brewed any beer, but has contracted with other companies to produce its products. In 2010, it was acquired by investor C. Dean Metropoulos, on whose watch the 4.74 percent ABV Pabst Blue Ribbon brand developed a cult following that turned the company’s image around. Despite its being a virtual brewer with no breweries, Pabst has more volume in the United States than any brewing company other than the Big Three.

The flagship brand for Anchor Brewing is their Steam Beer, which is still their most popular offering. (Anchor)

In the 1950-1975 era, as the biggest breweries grew bigger, and the regional breweries faded, mass-market beer gradually became “flavor neutral,” designed to appeal to a broader audience, and to do so on the basis of price, not flavor. This redefined American beer culture for at least two generations.

Rob and Kurt Widmer started their brewery in 1984, pioneered hefeweizen in American brewing and were part of making Portland, Oregon into a major craft brewing center. (Widmer)

Then, things started to change. Eventually, the craft brewing revolution would redefine the market the other way.

It was in 1965 that a recent Stanford University graduate named Fritz Maytag was given some startling news. The San Francisco brewery that brewed his favorite beer was about to go out of business. Dating back to 1896, the Anchor Brewing Company was typical of the hundreds of local breweries that had survived Prohibition only to be buried by the tide of mass merchandising that had created the national brands. For the price of a used car, Maytag bought a controlling interest in Anchor in 1965. The combination of chemistry, business, and tradition had an intoxicating effect on him. “I was made for this brewery,” he once told an interviewer. “It was a marriage made in heaven.” Though it would take a decade before the business was profitable, Fritz Maytag had seen to it that Anchor did not simply fade away. He also bought himself a career that would define the future of small-scale brewing in the United States.

The Deschutes Brewery started by Gary Fish in 1988 as a small brewpub in Bend, Oregon, but it grew into one of America’s largest brewers. (Deschutes)

In 1975 Maytag revived a tradition, long dormant in American brewing culture, of brewing an annual Christmas Beer, priding himself on using a completely new recipe every year. Though he departed from Anchor Brewing in 2010, he left a legacy of serious attention to detail and quality that remains with the company. The products include 4.9 percent ABV Anchor Steam Beer, which has been the brewery’s flagship product since before Maytag took over; 5.6 percent Anchor Porter; and 5.9 percent Liberty Ale, which was Anchor’s 1976 Christmas Beer.

Inspired by Fritz Maytag, the craft brewery revolution started with the now extinct New Albion Brewing of Sonoma, California, which was founded by Jack McAuliffe in 1976. At the same time that McAuliffe was getting started, there was a growing public awareness of beer styles—such as ales, wheat beers, and stouts—that were rare or even unknown in the United States.

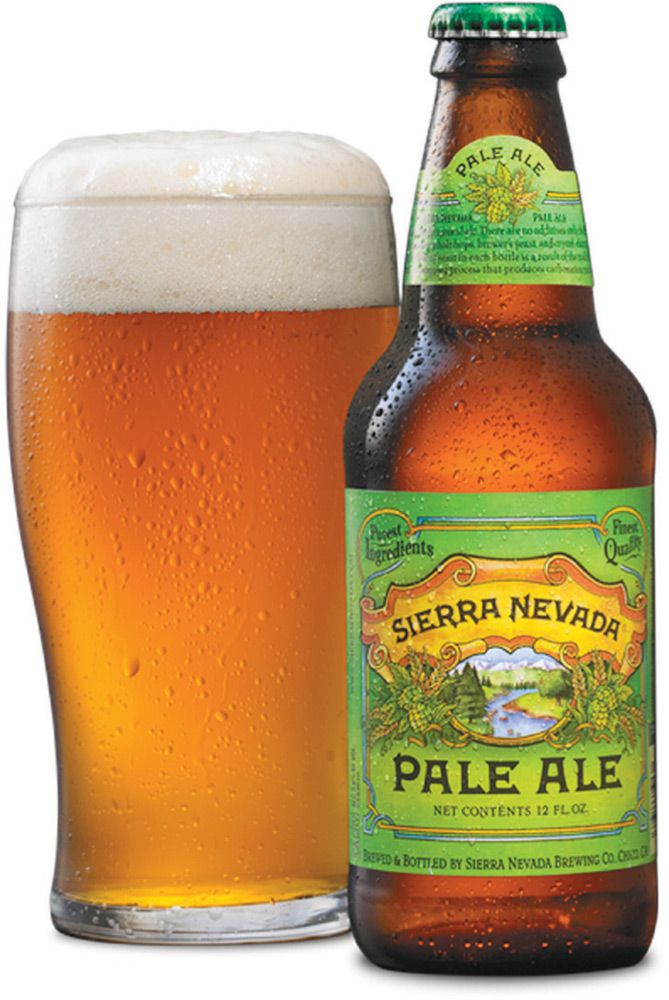

In 1979, Sierra Nevada Brewing was founded in Chico, California, by homebrewers Ken Grossman and Paul Camusi. It is notable that Sierra Nevada would go on to experience an extraordinary 1,500 percent growth surge during the 1990s that would place it solidly among the top ten American brewing companies.

The craft beer revolution spread to Colorado in 1980 with the opening of the Boulder Brewing Company (Rockies Brewing from 1993 to 2004) and to New York state as William Newman began brewing in Albany the following year. Paul Shipman’s Redhook Ale Brewery opened in Seattle in 1981. In Portland, Oregon, Kurt and Rob Widmer, who founded Widmer Brothers Brewing Company in 1984, went on to pioneer an American variation on the German hefeweizen (wheat beer) in 1986. They were also among the first breweries to introduce seasonal beers other than Christmas beers into America.

In 1980, Ken Grossman helped start Sierra Nevada Brewing in Chico, California, and grew it into one of America’s largest brewing companies. (Sierra Nevada)

In the early days, the new craft breweries were called microbreweries, the original definition of which was a brewery with a capacity under 3,000 barrels. By the end of the 1980s this threshold increased to 15,000 barrels as the demand for microbrewed beer first doubled and then tripled. Another new entity born of the craft brewing revolution was the “brewpub,” a microbrewery that both brewed and served its beer to the public on the same premises. Brewpubs had existed in the United States in the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries, but after Prohibition it was illegal in most states to both brew beer and sell it directly to the public on the same site. Changes in local laws since the early 1980s rescinded these outdated restrictions and made it possible for brewpubs to become widespread.

In Yakima, Bert Grant would open America’s first brewpub in more than a century in 1982, and others soon followed. Mendocino Brewing, which was established in the appropriately-named village of Hopland, about two hours north of San Francisco, opened in 1983 and was followed by Buffalo Bill Owens’ brewpub in Hayward, across the Bay from San Francisco. By the time that Allan Paul opened San Francisco Brewing in the old Albatross Saloon in 1986, there was a rush of new brewpubs opening throughout the United States. Mike and Brian McMenamin led the brewpub revolution into the Northwest in 1985 with the Hillsdale in Portland, and within four years they had six brewpubs in western Oregon. Today, McMenamins operates 65 brewpubs, microbreweries, music venues, hotels, and theater pubs across Oregon and Washington.

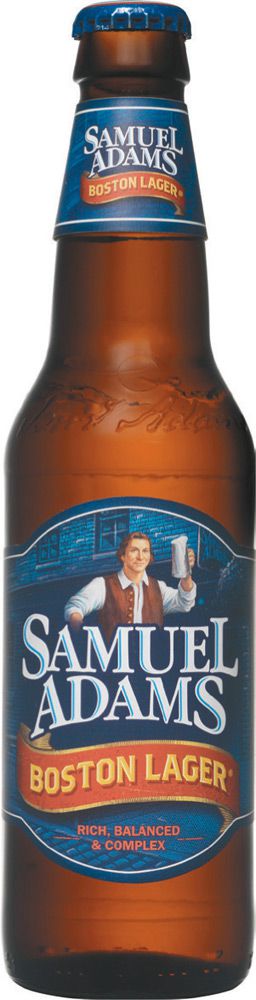

In 1984, Jim Koch founded the Boston Beer Company and created the Samuel Adams brand. Over time, his company became the largest craft brewer in America. (Boston Beer Company)

Gary Fish, who established the Deschutes Brewery as a small brewpub in Bend, Oregon, in 1988 is a case in point of the staying power of craft breweries. Said Fish of the maturing craft brew market of the 1990s, “This industry has more credibility now.…It has grown, and the quality of the beer has improved. Failures are just business, not a fad gone awry. We think there are very good times to come for this segment of the industry.”

Today, Deschutes is America’s twelfth-largest brewer in a much larger field. The American brewing industry that was down to fewer than 50 companies in 1980, had topped 1,500 by 2000 and surpassed 2,500 breweries a decade later.

Despite the disproportional differences in size and market share, the megabrewers took notice of the craft brewers and were befuddled by their popularity, but they did not ignore them. In the 1990s, they even tried to imitate them. Anheuser-Busch introduced an ersatz craft beer called Elk Mountain Amber Ale, and Miller produced its Red Dog. Despite much hype and fanfare, neither survived. Coors was more successful. They even started a “microbrewery,” called Sandlot at Denver’s major league ballpark. It was here in 1995 that brewer Keith Villa created 5.4 percent ABV Blue Moon Belgian White, a Belgian-style witbier. Coors eventually took the beer national, and it still remains. A decade later, in 2006, Anheuser-Busch rolled out its own 5.2 percent witbier called Shock Top. This brand later became the umbrella for a family of AB InBev seasonal beers which replaced the variants of the venerable Michelob brand in the company’s portfolio.

Anheuser-Busch also moved to acquire a minority stake in several craft brewing companies. In 2011, they bought a controlling share of the Goose Island Brewery, started in 1988 in Chicago. Goose Island had become famous in the early twenty-first century for its critically acclaimed 13 percent ABV Bourbon Country Stout.

Among the first craft breweries in the East outside the Empire State were D.L. Geary Brewing in Portland, Maine, and Catamount Brewing in White River Junction, Vermont, which opened in 1986 and 1987 respectively. Another early Eastern micro was Mass Bay Brewing—famous for the Harpoon brand.

On the East Coast, many companies of craft brewing’s first generation did not immediately open breweries but contracted with existing regional breweries to produce their beer. Among these was entrepreneur Jim Koch, who formed his Boston Beer Company in 1985 to produce Samuel Adams Lager. His idea was to create an American beer, which he named for the eighteenth-century Boston patriot and maltster Samuel Adams. In 1988, Koch began brewing at the renovated former Haffenreffer Brewery in an old brewing neighborhood in Boston. By the early 1990s, Sam Adams was available throughout the United States.

In 1988, Ed Stebbins and Richard Pfeffer started Gritty McDuff’s as a brewpub in Portland Maine. Since then, Gritty McDuff’s has opened additional locations in Freeport and Auburn, and has become a Maine institution. (Gritty McDuff’s)

With brewing operations in Boston and at a larger facility in Breinigsville, near Allentown, Pennsylvania, the Boston Beer Company produces a sizable number of products, including more than a dozen core beers as well as many annually rotating seasonal beers and many that are brewed on a temporary basis. The flagship products are 4.9 percent ABV Boston Lager (the first Samuel Adams beer, launched in 1984) and 5.4 percent Boston Ale, first released in 1987 to celebrate the opening of the Boston brewery. Other core products include 4.9 percent Cream Stout (since 1993) and 5.5 percent Revolutionary Rye (since 2010). Seasonals include 5.6 percent Winter Lager (since 1989) and 5.3 percent Summer Ale (since 1996). Other beers have included 10.3 percent Infinium, a 2010 limited release of a collaboration with Germany’s Weihenstephan. In 2013, in cooperation with Jack McAuliffe, Boston’s Jim Koch reintroduced the New Albion brand, the original microbrew, on a limited basis. A 6 percent ABV pale ale, it is said to approximate the 1976 original.

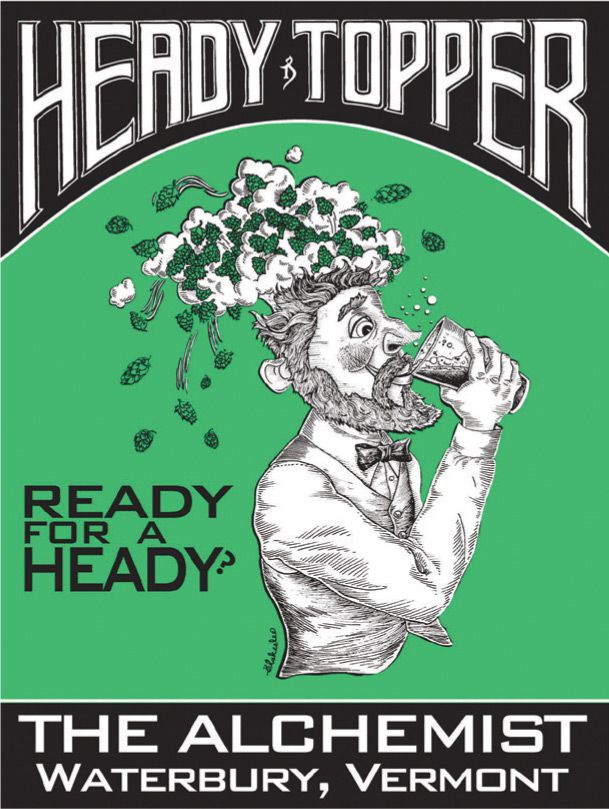

John Kimmich started the Alchemist Brewery in Waterbury, Vermont in 2003. His Heady Topper has a cult following throughout the Eastern United States and is rated among America’s top ten by leading beer enthusiast journals. (Alchemist)

The new microbreweries were not the only institutions that would benefit from Fritz Maytag’s bold experiment. Among the other beneficiaries of the interest in craft brewed beer were the other independent regional brewers who, like Anchor, had been bucking the consolidation trend for decades. Just as beer drinkers were discovering a new generation of brewers who were recapturing beer and brewing styles that were an homage to the brewers of their grandfathers’ day, others were enjoying beer from the same breweries that had supplied their grandparents. A case in point is the brewery founded in 1829 by David Gottlob Jüngling in Pottsville, Pennsylvania. D.G. Yuengling Brewing is now the oldest brewery in the United States. In 1985, as the craft brewing movement was just beginning to sweep the country, Richard L. “Dick” Yuengling bought the family “microbrewery” from his father. The brewery’s success was a corollary to the success of the craft brewing movement.

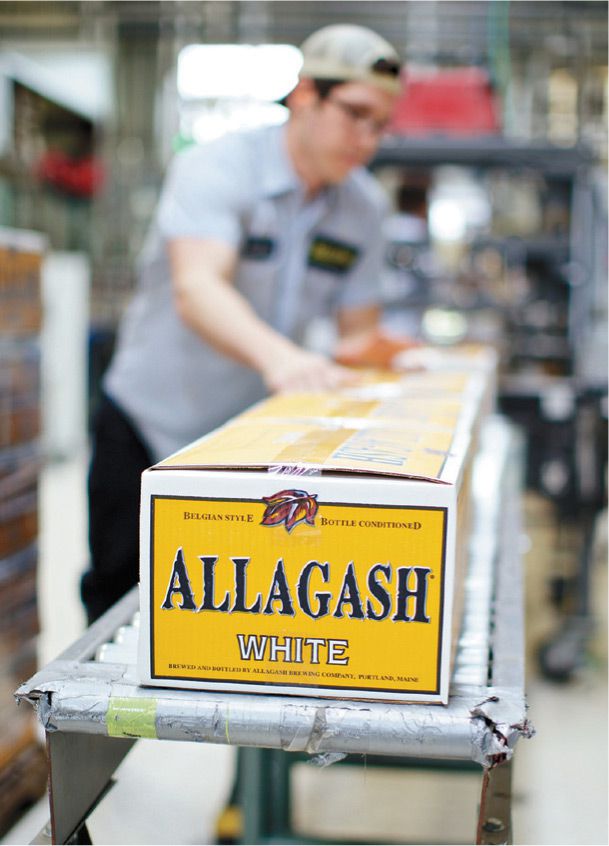

Scenes from the Allagash Brewing Company of Portland, Maine. Allagash White is the flagship brand. Curieux, an 11 percent ABV tripel, was the “first foray into barrel aging…[placed into] bourbon barrels for eight weeks in our cold cellars.” (Allagash)

Still headquartered in Pottsville, Yuengling brews there as well as in Tampa, Florida. Widely distributed in the Eastern United States, Yuengling’s products include 4.4 percent ABV Yuengling Traditional Lager, 5.4 percent Lord Chesterfield Ale, and 4.7 percent Yuengling Porter, which was in the portfolio for many decades in the twentieth century before craft brewers rediscovered porter as a style.

Genesee Brewing (known as High Falls Brewing between 2000 and 2009) of Rochester, New York, was one of numerous fading regional breweries in the 1980s when it reinvented itself as a contract brewery of other companies’ brands. In 2009, it was acquired by the investment firm KPS Capital Partners, who rolled it into a holding company called North American Breweries, to which they added the United States operations of Canada’s Labatt. In 2012, this entity was sold to Costa Rica–based Florida Ice & Farm, the parent company of Cervecería Costa Rica.

Also part of the holdings of North American Breweries at the time was Magic Hat Brewing, a craft brewery started in 1994 in Burlington, Vermont. In 2008, Magic Hat had acquired Pyramid Breweries of Seattle. Originally started as Hart Brewing in 1984, Pyramid had grown into a large regional brewing company, with brewery restaurants across the Pacific Northwest and California, and in 2004 had acquired the Portland Brewing Company, makers of the MacTarnahan’s brand.

In the twenty-first century, with Pabst as a virtual brewer and the Big Three plus Genesee now foreign owned, Yuengling, Koch’s Boston Beer, and Grossman’s Sierra Nevada became the three largest brewing companies owned in the United States who actually brew beer in the United States. The annual output for both Yuengling and Boston Beer is roughly tied at around 2.5 million barrels, while Sierra Nevada produces about 800,000 barrels.

Sierra Nevada has brewed at the same plant in Chico since 1989 and added a new facility in Mills River, North Carolina, in 2014, which will greatly expand its market presence in the East. The flagship product since the beginning has been 5.6 percent ABV Sierra Nevada Pale Ale. Other products dating from the early days include 5.6 percent Sierra Nevada Porter and 5.8 percent Sierra Nevada Stout. Another product dating to the 1980s, and now a seasonal “special release,” is 9.6 percent Bigfoot Barleywine Style Ale. Two products released in 2009 which earned high marks from critics were 7.2 percent Torpedo, an IPA, and 6.7 percent Chico Estate Harvest Ale, originally released in 2008, which was made with organic hops and barley grown on land that is part of the brewery premises.

Across the continent, meanwhile, one finds an especially high concentration of highly regarded craft brewers in New England. John and Jen Kimmich opened The Alchemist in Waterbury, Vermont, in 2003 as a brewpub and began brewing a range of beers. One of the beers that attracted special attention was their unfiltered 8 percent ABV Heady Topper double IPA, which became so popular that they began packaging it for retail sale. Thought it is unavailable outside the immediate area, it has attracted worldwide attention. In 2013, Beer Advocate rated it as the number-one beer in the world, calling it “a complex web of genius.”

Shaun Hill’s Hill Farmstead Brewery on the family’s Vermont farm was rated by the RateBeer website as the best brewery in the world in 2013. (Bob M. Montgomery photos)

Allagash Brewing, founded in Portland, Maine, in 1994 by Rob Tod, is best known for their highly regarded flagship brand, 5 percent ABV Allagash White, a widely distributed “interpretation of a traditional Belgian wheat beer. Brewed with a generous portion of wheat and spiced with coriander and Curacao orange peel.” Other beers include their 7 percent Dubbel Ale, their 9 percent Tripel Ale, and 11 percent Allagash Curieux, made by aging Tripel Ale in bourbon barrels for eight weeks in cold cellars. The aged beer is then blended back with a portion of fresh Tripel.

The first of several Heartland Brewery locations opened on Union Square in New York City in 1995. (Bill Yenne photo)

Gritty McDuff’s, also in Portland, started in 1988 as a brewpub in which this author spent a memorable snowy evening about a decade later. Another pub with a larger brewery opened in Freeport in 1995, and a third brewpub was added in Auburn in 2005. The bottled product portfolio includes Original Pub Style, which is based on the early draft beers. Other products include 5 percent ABV Maine’s Best IPA and 5 percent Gritty’s Best Bitter as well as seasonal 6 percent Halloween Ale, 6.2 percent Christmas Ale, and 4.9 percent Vacationland Summer Ale.

The Hill Farmstead Brewery, located at the end of a dirt road near Greensboro, Vermont, is a true farmhouse brewery that happened to be named as the 2013 Best Brewery in the World by RateBeer, who listed eight of their offerings among its top ten new beers in the world. Owners Shaun and Darren Hill name the beers of their popular “Ancestral Series” after their own ancestors, who have lived on the same farm for more than two centuries. Ephraim, for example is named for great-great grandfather Ephraim Hill, who was born there in 1823. The brewery is several hundred feet downhill from the land that he and his father settled. The beer is a 9.8 percent ABV unfiltered and double dry hopped imperial IPA. Topping RateBeer’s list is Ann, a 6.5 percent saison aged in French oak wine barrels, and Society & Solitude #2, a 9.5 percent black ale.

Filling barrels for aging at the Rock Art Brewery in Morrisville, Vermont. (Rock Art)

Matt Nadeau started his Rock Art Brewery in 1997 in his Johnson, Vermont, basement, but moved to a larger brewery in nearby Morrisville in 2001. The beers include 7.2 percent ABV Rigderunner, 5 percent Whitetail, 8 percent Double IPA, and a 10 percent barleywine called Vermonster.

In upstate New York, many breweries have come and gone since William Newman’s pioneering efforts in the 1980s. Beginning in the 1990s, brewpubs such as Big House Brewing and Malt River Brewing came and went, while Brown’s Brewing and the Albany Pump Station came and stayed. Scott Vaccaro’s Captain Lawrence Brewing in Elmsford, New York, came to stay as well. Named for Captain Samuel Lawrence, who served in the Westchester County Militia in the American Revolution, the brewery’s lineup includes 9 percent Captain’s Reserve Imperial IPA.

New York City’s first, and long departed, craft brewing companies included Manhattan Brewing, a brewpub started by Robert D’Addona in 1984 in a former Con Edison substation in Soho, as well as Old New York Brewing, known for its Amsterdam Amber, which was brewed under contract by F.X. Matt Brewing in Utica, in upstate New York.

F.X. Matt, also known as West End Brewing, would evolve into one of the largest of the contract brewers in the East during the late 1980s and early 1990s. Originally founded in 1853, the company that had long been famous for its own Utica Club brand would contract brew for a number of eastern companies during the 1980s and 1990s.

New York City has seen the comings and goings of a number of brewpubs since Manhattan Brewing, including the now defunct Zip City and the Heartland Brewery chain, which started in 1995 and has grown to multiple Manhattan sites. Heartland brews for these locations at a production facility in Brooklyn. Best known of the craft brewers in that borough is the Brooklyn Brewery, started in 1987 by Steve Hindy and Tom Potter. Their beer was brewed upstate at F.X. Matt until they acquired a brewery site in Brooklyn in 1996. As a brewmaster, they hired Garrett Oliver, formerly with Manhattan Brewing and the author of The Brewmaster’s Table: Discovering the Pleasures of Real Beer with Real Food. The Brooklyn beers include 4.5 percent ABV Brooklyn American Ale, 10 percent Brooklyn Black Chocolate Stout, and 4.5 percent Blanche De Brooklyn.

Rosemarie Certo of Dock Street Brewing. (Dock Street)

Down the shoreline, the Tun Tavern in Atlantic City is an example of a single-site brewery and restaurant with an enviable location. Named for Philadelphia’s historic eighteenth-century Tun Tavern, it opened in 1998.

In Pennsylvania, the first generation of craft brewers, circa 1986, included Jeff Ware and Rosemarie Certo of Dock Street in Philadelphia and Tom Pastorius, who started Pennsylvania Brewing, aka Penn Brewery, in Pittsburgh. Both contracted production elsewhere until 1989, when brewpubs were legalized in the state, and then both opened as their own facilities. Dock Street existed as both a brewpub and an offsite bottling operation until 2000.

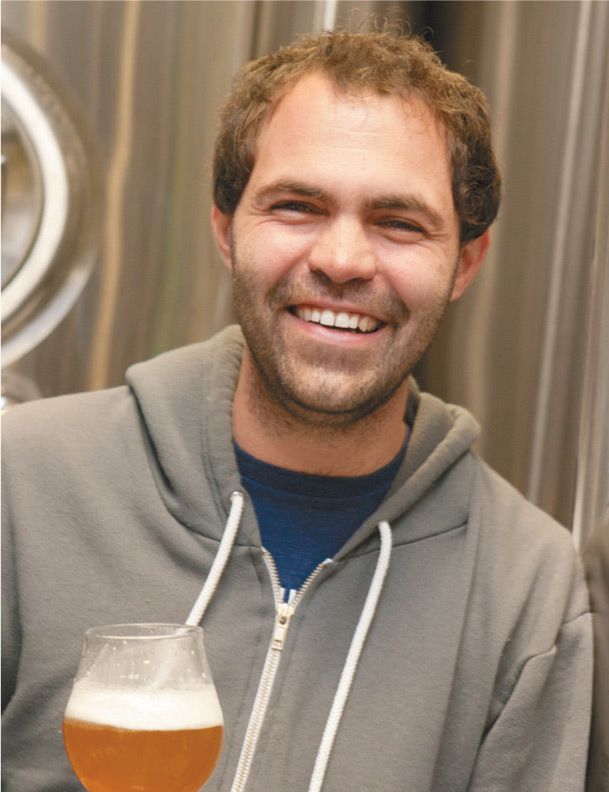

Joe Coffee Porter and Walt Wit witbier from Philadelphia Brewing. (Philadelphia Brewing)

Jeff Ware moved overseas, but Rosemarie Certo reacquired the brand and reopened Dock Street as a brewpub in 2007. Pastorius restored the former Eberhardt & Ober Brewery. The company was acquired by an investment firm in 2003 and sold to other investors in 2009.

Chris and John Trogner of Tröegs Brewing in Pennsylvania. (Tröegs)

Part of a newer generation is Philadelphia Brewing, founded in 2007 by Bill Barton, Nancy Barton, and Jim McBride. Brewing was originally outsourced, but operations are now in the nineteenth-century Weisbrod & Hess Oriental Brewing building, where they brew 5 percent ABV Joe Coffee Porter and 4.2 percent Walt Wit witbier.

Tröegs Brewing was founded in 1996 in Harrisburg, Pennsylvania, by John and Chris Trogner, but relocated to larger facilities in Hershey in 2011. The product line includes a larger than typical proportion of seasonal beers. Year-round beers include 4.8 percent ABV Dreamweaver wheat ale and 8.2 percent Troegenator double bock. Autumn-December beers include 11 percent Mad Elf, and spring beers include 9.3 percent Flying Mouflan barleywine.

The Dogfish Head portfolio includes 90 Minute IPA, Indian Brown Ale, 60 Minute IPA, Midas Touch, and Palo Santo Marron. All are high in both ABV and IBU (International Bitterness Units). (Dogfish Head)

The Dogfish Head Brewery was started in 1995 in Milton, Delaware, by Sam Calagione, but it was in the twenty-first century that the popularity of the beer and the notoriety of the brand became the subject of national media attention. Between 2003 and 2006, the brewery experienced a 400 percent growth spurt, and it has been featured in several television documentaries including the Discovery Channel’s Brew Masters series. Calagione started with a brewpub in Rehoboth Beach and has licensed the brand to Dogfish Head Alehouse brewpubs in Maryland and Virginia. He is also the author of several books on the business of brewing.

Calagione is part of the “extreme beer” school of brewing, which experiments with large quantities of non-traditional ingredients, high ABV, and extreme quantities of bittering hops. Dogfish Head’s flagship product line is a series of IPAs whose names indicate the boil time during which hops are continuously added to the wort while brewing. This group includes the 6 percent ABV 60 Minute IPA (rated at 60 IBU), introduced in 2003, and 9 percent 90 Minute IPA (90 IBU), introduced in 2001. There is also a limited-release 18 percent 120 Minute IPA with a bitterness of 120 IBU. Other year-round brands are 9 percent Midas Touch, introduced in 1999 and made with honey, white muscat grapes, and saffron; 12 percent Palo Santo Marron, which is an unfiltered brown ale fermented in Paraguayan palo santo wood; and 8 percent Raison D’Etre, a Belgian strong dark ale brewed with beet sugar and raisins. Dogfish Head has also brewed beer in collaboration with other brewers, such as Epic Brewing of New Zealand, in which the beer was fermented with tamarillo (a tomato-like fruit also called the tree tomato) which had been smoked using wood chips from the Pohutakawa tree. Other collaboration partners have included Stone Brewing, Three Floyds, and Victory Brewing. For the 5.5 percent Repoterroir in 2011, Dogfish Head teamed with Sierra Nevada, Avery Brewing, Allagash Brewing, and Lost Abbey.

Sam Calagione of Dogfish Head. (Dogfish Head)

Tap handles at the Flying Dog Brewery. (Flying Dog)

The Flying Dog Brewery started as a brewpub in Aspen, Colorado, in 1990, acquired a production facility in Denver in 1994, and purchased Frederick Brewing in Frederick, Maryland, in 2006. In 2008, the Denver plant closed and production was moved east. Of note were the labels, designed by illustrator Ralph Steadman. Products include 5.5 percent ABV Doggie Style Classic Pale Ale, 8.3 percent Raging Bitch Belgian-Style IPA, and 9.2 percent Gonzo Imperial Porter.

Scenes from the award-winning Blue Mountain Brewery in Afton, Virginia. Started in 2007, it is part of the “Brew Ridge Trail,” a series of craft breweries along the along the Blue Ridge Parkway. (Blue Mountain)

In Virginia, the state’s original large-scale craft brewer, Old Dominion, was relocated to Delaware in 2006 after 17 years, but around that time a series of new brewery restaurants were established along the Blue Ridge Parkway. The first of these was the Starr Hill Brewery, which moved from Charlottesville to Crozet in 2005. In 2007, the Blue Mountain Brewery opened in Afton, and in 2008 Devils Backbone Brewing Company arrived in Roseland. Blue Mountain products include 5.9 percent ABV Full Nelson Virginia Pale Ale and 10 percent Dark Hollow Artisanal Ale.

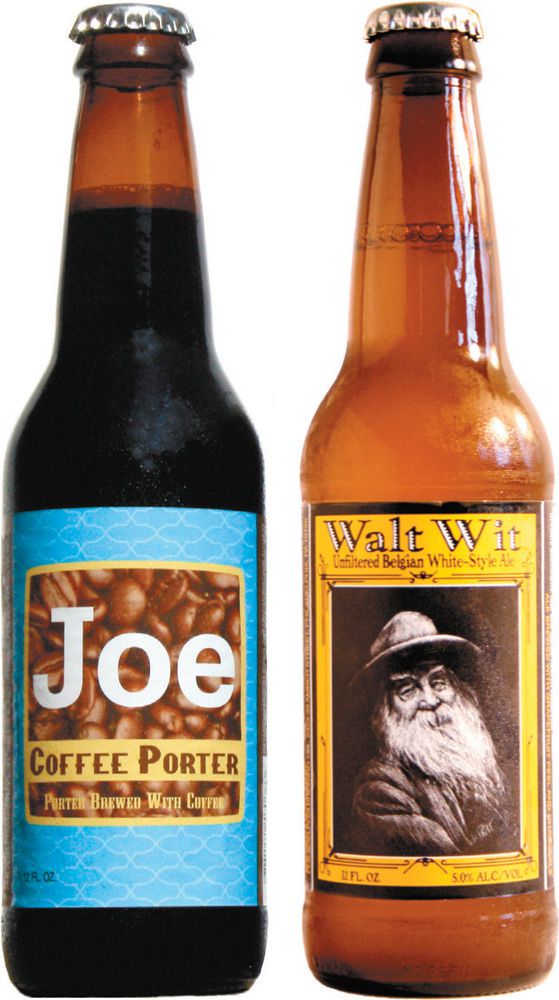

Beers from Cigar City Brewing of Tampa, Florida include 9 percent ABV Bolita Double Nut Brown Ale, 11 percent Cognac Barrel Aged Imperial Sweet Stout, and 7.5 percent Humidor Series IPA. (Cigar City)

Cigar City Brewing in Tampa was, according to its mission statement, “founded with two goals in mind. The first to make the world’s best beer and the second to share with people near and far the fascinating culture and heritage of the Cigar City of Tampa…[f]rom its past as the world’s largest cigar producer to its Latin roots.” Cigar City consistently wins awards and critical acclaim. In 2012, it was named as the number four “Best Brewer in the World” by RateBeer. Among its most highly rated beers are 11 percent ABV Hunahpu’s Imperial Stout, 11 percent Marshal Zhukov’s Imperial Stout, 8.5 percent Good Gourd Imperial Pumpkin Ale, 7.5 percent Jai Alai IPA, 9 percent Bolita Double Nut Brown Ale (named in honor of the popular Bolita games), 11 percent Cognac Barrel Aged Imperial Sweet Stout, and 7.5 percent Humidor Series IPA.

Back in the 1970s, in the heyday of Willie Nelson and the “Outlaw” movement in country music, San Antonio had been the brewing capital of the Lone Star State and the “National Beer of Texas” was San Antonio–brewed Lone Star. However, the brewery soon went through a revolving door of ownership before being closed permanently in 1996. The leading beer in Texas today is a brand that has been around since 1909 and is brewed by one of the top ten brewing companies in the United States. This is Shiner, from the Spoetzl Brewery in Shiner, Texas, south of San Antonio. Founded by Kosmos Spoetzl, a German who once brewed in Egypt, the brewery was not on the national radar until Carlos Alvarez of San Antonio bought the company in 1989 and increased sales eight-fold by the early twenty-first century. Today, the “National Beer of Texas” is probably 4.4 percent ABV Shiner Bock, a beer that his been around for decades and is finally getting its due. Other beers include 5.5 percent Shiner Hefeweizen and 4.9 percent Shiner Kosmos Reserve.

Spoetzl Brewery’s Brewmaster Jimmy Mauric on the bottle line, and Shiner Bock, the flagship brand. (Spoetzl)

Boulevard Brewing, who began marketing its beer in 1989, grew into the largest specialty brewer in the Midwest by the twenty-first century. Founded by John McDonald, Boulevard underwent small expansions in 1999 and 2003 and a major enlargement of operations in 2005 that gave it a 700,000-barrel annual capacity for its 5.4 percent ABV Pale Ale, 4.4 percent Unfiltered Wheat Beer, 6 percent Bully! Porter, 8.5 percent Tank 7 Farmhouse Ale, 8.5 percent Double-Wide IPA, and various seasonal beers.

August Schell Brewing in New Ulm, Minnesota, was started in 1866 by August Schell, survived the ups and downs of industry consolidation in the twentieth century, and is today the second-oldest family-owned brewery in the United States after Yuengling. Having acquired the classic Grain Belt brand in 2002, it is now the largest brewing company in the northern Midwest. Its flagship is 4.8 percent ABV Original Deer Brand lager, complemented by 5 percent FireBrick. Seasonal beers include 4.4 percent Hefeweizen and 5.1 percent Schmaltz’s Alt. The Grain Belt portfolio includes 4.6 percent Grain Belt Premium and 4.7 percent Grain Belt Nordeast. Schell recently released The Star of the North, their 3.5 percent interpretation of a traditional Berliner Weisse.

KBS (Kentucky Breakfast Stout) and Double Trouble IPA from Founders Brewing. KBS is rated by beer enthusiast journals in America’s top ten. (Founders)

Another Minnesota brewery of note is Summit Brewing, started in St. Paul in 1986 and now the state’s second largest. They are known for their 5.5 percent ABV Extra Pale Ale, 6.4 percent IPA, and 6.6 percent Oktoberfest.

Leading Midwest brands include Deer Brand and Schmaltz’s Alt from Schell; Great Northern Porter and Pilsner from Summit Brewing, and Unfiltered Wheat from Boulevard in Kansas City. (Courtesy of the breweries)

Like Schell, the Stevens Point Brewery, aka “Point,” has been brewing since the nineteenth century. Founded in Stevens Point, Wisconsin, in 1857 by George Ruder and Frank Wahle, Point provided beer for troops during the Civil War and went through a number of private owners before being sold to Barton Beers, a Chicago-based distributor, in 1992. Since being resold in 2002 to Milwaukee-based investors, it has acquired outside brands, including Augsburger from the late megabrewer Stroh, and those of the Wisconsin microbrewery James Page Brewing, which existed from 1986 to 2005. Once available only within a narrow radius of Stevens Point, the products are now sold in most states. These include 4.7 percent ABV Classic Amber, 5.38 percent Belgian White, 5.2 percent Black Ale, 5.4 percent Cascade Pale Ale, 6.5 percent Beyond The Pale IPA, 3.5 percent Drop Dead Blonde, 5 percent Burly Brown, 3.65 percent Horizon Wheat, 4.7 percent Amber Classic, and the iconic 4.5 percent Point Special Lager.

Part of the portfolio from the Stevens Point Brewery in Wisconsin. Dating back to 1857, it is one of the oldest privately-held breweries in the United States. (Stevens Point)

The “World's Largest Six Pack” in LaCrosse, Wisconsin is a group of a half dozen fermenters built in 1969 by G. Heileman, and now owned and operated by the City Brewery. (Bill Yenne photo)

Founders Brewing Company in Grand Rapids, Michigan, produces some of the most highly-rated beers in the Midwest. Their 11.2 percent ABV Founders KBS (Kentucky Breakfast Stout) is rated by Beer Advocate among the top ten in the United States. RateBeer named Founders as the third-best brewery in the world in 2013. Founders was founded in 1997 as Canal Street Brewing by homebrewers Mike Stevens and Dave Engbers. They named the brewery after the street where many early breweries had been and pictured these on their labels with the word “Founders” above. This name caught on, and the company name changed. Among their other highly rated beers are 8.3 percent Founders Breakfast Stout, 10.5 percent Founders Imperial Stout, an 9.4 percent Founders Double Trouble IPA.

Kim Jordan of Colorado’s New Belgium Brewing, and highlights from her portfolio. (New Belgium)

New Belgium Brewing in Fort Collins, Colorado, well known for its 5.5 percent ABV Fat Tire Amber Ale, is the second-largest brewer in the Mountain West, after Coors, and the eighth largest in the United States. The story began in 1991 when homebrewer Jeff Lebesch began operating commercially. On a trip across Belgium on a fat-tired bicycle, Lebesch was inspired by the imaginative beers that he discovered in Belgium—hence the brewery name and the brand name. In the early days, it was a family business, with Lebesch’s wife, Kim Jordan, as part of the team. They have since divorced, Lebesch left the company in 2001, and Jordan is now chief executive. The product line includes 5.6 percent 1554 Enlightened Black Ale, 7 percent Abbey Belgian Style Ale, 6.5 percent Ranger IPA, 6.2 percent Snow Day Winter Ale, and 7.8 percent Trippel Belgian Style Ale.

Highlights from among the extensive offerings from Odell Brewing. (Odell)

Also in Fort Collins, but less than 10 percent the size of New Belgium, is Odell Brewing, started in 1989 by Doug Odell, his wife Wynne, and his sister Corkie. Their beers include 4.2 percent ABV Easy Street Wheat, 5 percent Levity Ale, 7 percent IPA, 5.2 percent 5 Barrel Pale Ale, 5.3 percent 90 Shilling Ale, 5.5 percent 90 Oak-Aged Shilling Ale, 5.5 percent Cutthroat Porter, and 9.2 percent ABV Myrcenary Double IPA.

The Odell Brewery in Fort Collins, Colorado. (Odell)

A six-pack of 5.3 percent ABV Moose Drool Brown Ale, the flagship product from Big Sky Brewing of Missoula, Montana, and the man who brews it, head brewer Matt Long. (Loren Moulton, Big Sky)

Products from Great Northern Brewing of Whitefish, Montana include 4.75 percent Wheatfish Wheat Lager, 5.9 percent Snow Ghost Winter Lager, and 5.7 percent Going To The Sun IPA. (Great Northern)

Montana, meanwhile, has had a long history of craft brewing, beginning with Montana Beverages of Helena, which brewed between 1982 and 1999 under the fondly remembered brand of the Kessler Brewing Company, which itself had existed in Helena from 1865 to 1958. They also produced products for craft brewing companies throughout the West. Helena is now home to Blackfoot Brewing and Lewis & Clark Brewing. Another early Montana brewer is Bayern Brewing, started in Missoula in 1987 by Thorsten Geuera and Jürgen Knöller and now the oldest operating brewery in Montana. The state’s largest brewery is Big Sky Brewing started in Missoula in 1995 as a microbrewery by Neal Leathers, Bjorn Nabozney, and Brad Robinson. It is now a major regional brewery with sales in much of the United States. Its flagship brand is 5.3 percent ABV Moose Drool Brown Ale, while other beers include 4.7 percent Scape Goat Pale Ale, 6.2 percent Big Sky IPA, 7.2 percent Powder Hound Winter Ale, 4.8 percent Summer Honey, and 4.7 percent Montana Trout Slayer Wheat Ale.

Classic labels of some of the early craft beer brands in the Pacific Northwest include Seattle’s Redhook ESB, Full Sail Amber Ale and Full Sail Wassail Winter Ale, and Dead Guy Ale from Rogue Ales of Newport, Oregon. All are still brewed, though labels have changed. (Author’s collection)

Another notable Montana brewery is Great Northern Brewing in Whitefish, started in 1995 by Minott Wessinger, the great-great grandson of Oregon brewing legend Henry Weinhard. The flagship beer is 4.5 percent ABV Black Star, a double-hopped golden lager. Production of this beer was suspended in 2002 when Wessinger left the company to pursue other interests. Both Wessinger and Black Star returned in 2010. Other products include 4.75 percent Wheatfish Wheat Lager, 4.6 percent Wild Huckleberry Wheat Lager, 5.7 percent Going To The Sun IPA, and 5.9 percent Snow Ghost Winter Lager, a Munich-style dunkel.

Rogue Brewmaster John Maier with Chuck Linquist and Rogue founder Jack Joyce at Rogue’s Bayfront brewpub in Newport in 1991. (Bill Yenne photo)

The Pacific Northwest quickly became one of the most important—or, by local reckoning, the most important—centers of craft brewing in the Western Hemisphere. Back in the twentieth century, the Northwest had been home to three major household-name regional breweries whose geographic scope was much greater than most strictly regional brewing companies east of the Rockies. Each of them withered late in the century under competition from national brands. Blitz-Weinhard in Portland, Oregon, which originated with Henry Weinhard in 1856, was closed in 1999 after acquisition by Miller Brewing. Olympia Brewing Company dates back to the brewery established in 1896 in Tumwater, Washington, by Leopold Schmidt, a German immigrant from Montana. Sold to Pabst in 1983, it later passed to Miller and was closed in 2003. The Rainier brand from Seattle dates back to 1884 at a brewery started in 1878. The Rainier brand and brewery was acquired in 1935 by Emil Sick, who used it as the flagship of an international empire of breweries stretching from Oregon to Montana to Alberta that survived until the 1970s. The Seattle brewery was later sold to Pabst and closed in 1999.

Brewmaster Cam O’Connor at the Deschutes Brewery. (Deschutes)

Fast forward to the craft brewery revolution—the next big grouping of Northwest names included Redhook in Seattle (1991); Full Sail in Hood River, Oregon (1987); Deschutes in Bend, Oregon (1988); Rogue in Newport, Oregon (1988); and a large group of breweries in Portland. These included BridgePort (1984), Portland Brewing (1986), and Widmer Brothers (1994). In 2008, two of the largest of these, Redhook (now with breweries Woodinville, Washington and Portsmouth, New Hampshire) and Widmer, merged to form the NASDAQ-traded Craft Brew Alliance (CBA).

Popular brands, including the flagship. As the company notes “with a dark beer as our first and flagship brand, Black Butte defined Deschutes as a radical player.” (Deschutes)

While brewing and brands remained distinct, the joint venture, especially though a minority ownership by AB InBev, gave them a substantially improved nationwide marketing and distribution network. In 2010, Kona Brewing joined the CBA. Today, the CBA ranks ninth among all American brewing companies and Deschutes is in twelfth place.

Redhook brands include 5.8 percent ABV Redhook ESB, 6.2 percent Redhook Long Hammer IPA, and 6 percent Redhook Winterhook. Widmer’s product line is headed by its flagship 4.9 percent Widmer Hefeweizen, the most visible wheat beer on the West Coast, as well as 5.7 percent Drifter Pale Ale and 6.5 percent Pitch Black IPA.

American Beer Festivals

The Great American Beer Festival (GABF), hosted annually in Denver by the Brewers Association, the American craft brewers’ trade group, is the largest paid-admission beer festival in the United States. It has an annual attendance of close to 50,000 patrons sampling roughly 3,000 beers from 500 American breweries. Started in 1982 by Charlie Papazian, the three-day event has grown in importance through the years as the gold, silver and bronze medals awarded in more than 80 style categories are considered among the brewing community as the definitive measure of quality. The Brewers Association also hosts the World Beer Cup, an international beer competition heavily weighted to American brewers.

One of the biggest and most popular American regional beer festivals is the Oregon Brewer’s Festival, held in July since 1988 in Portland’s Tom McCall Waterfront Park. It is attended by more than 60,000 people. Other important festivals include the San Francisco International Beer Festival, started in 1983 and held each May, and New York City’s Brewtopia Great World Beer Festival, which was started in 2002 and is held in October. Also in the East, the Mid-Atlantic Beer Festival, which began in 2001, has been held both Baltimore and Washington, DC.

(Festival photo of J.R. Hubbard and Mike Bolos by the author. Commemorative coasters from the author’s collection)

Various cities around the United States also play host to Oktoberfest celebrations, with some of the largest and best known being those in Cincinnati, Ohio; San Francisco; Denver and Leavenworth, Washington.

In recent years, the event calendars in many American cities have come to include an annual “Beer Week,” often sponsored by local brewers’ organizations. Cincinnati, New York, Grand Rapids and San Francisco hold theirs in February; Chicago, San Antonio, Seattle, Madison, Wisconsin, and Asheville, North Carolina all have their Beer Weeks in May; Philadelphia’s is in June; Austin’s is around the end of October; and Houston’s is in November.

The Deschutes portfolio is headed by 5.2 percent ABV Black Butte Porter and 5 percent Mirror Pond Pale Ale but also includes 11 percent The Abyss, a highly regarded imperial stout.

A wide-angle look into the busy inner workings of Seattle’s Pike Brewery. (Pike Brewery)

Having dwelt upon the Northwest’s new generation of mega-brewers, it should be mentioned that the region is literally alive with such a wonderland of microbreweries and brewpubs that a beer traveler could not exhaust them, even on an extended visit. There is the Bayfront Brewery in Newport, Oregon, the showplace of Rogue Ales (and fond memories for this author) since 1989. A traveler might stop here for a 6.5 percent ABV Dead Guy Ale, a 6 percent Smoke Ale, or a 6.1 percent Shakespeare Oatmeal Stout, one of Rogue’s original beers.

Some highlights from the Pike portfolio include 6.5 percent ABV Pike IPA, 7 percent Pike XXXXX Extra Stout, 9 percent Monk’s Uncle Tripel, 9.9 percent Pike Old Bawdy Barley Wine, and the annual 5.5 percent Auld Acquaintance Hoppy Holiday Ale. (Pike Brewery)

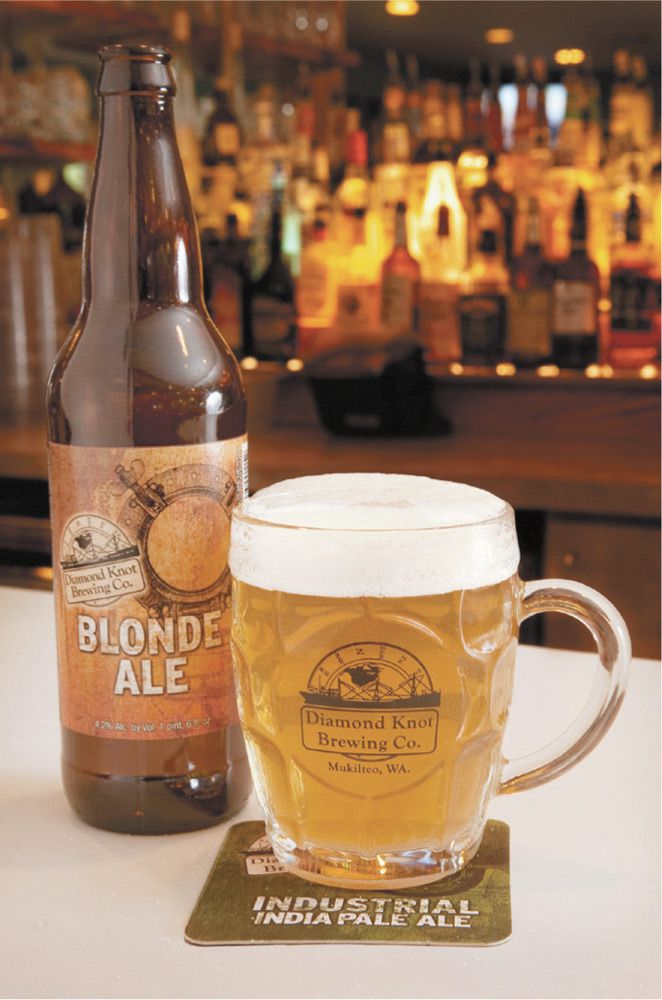

Also overlooking the salt water is Diamond Knot Brewing, a brewpub started back in 1994 in Mukilteo, Washington. According to the Seattle Times, they are “widely regarded as producing some of the best, most innovative beers in the region.” In Seattle itself, the traveler may find Georgetown Brewing, a brewpub started in 2002 by Manny Chao and Roger Bialous.

Inside the pub at the Pike Brewery, with founders Rose Ann and Charles Finkel, and a pasta pairing featuring Pike Pale Ale. (Pike Brewery)

If the beer traveler has time for but one Seattle stop, it should be the Pike Pub & Brewery in the Pike Place Market. It was started in 1989 by Charles and Rose Ann Finkel, who, though their company, Merchant du Vin, were among the first importers of select specialty beer from Europe. As the company’s official fact sheet points out, Merchant du Vin “became the exclusive agent for some of Europe’s finest independent brewers including Ayinger, Lindemans, Melbourn Bros, Orval, Pinkus, Samuel Smith and Traquair House. Their's was the first company to offer a range of Belgian beers; to work with British brewers to create long forgotten styles like Oatmeal Stout, Porter, Imperial Stout and Scotch Ale; and to repackage [their Celebrator, a] classic Bavarian doppelbock under a private label that eventually became the Ayinger Brewery’s world-wide brand. They introduced many people including many early craft brewers, to the glories of great beers.” Indeed, this is how this author first came to know them.

At Seattle's Georgetown Brewing, the tap handles and a brewer adding hops to the brew. (Georgetown)

Charles Finkel is one of the most important men in American beer connoisseurship in the past generation. Among other things, he was also a pioneer in the art of beer and food pairings. He is remembered as the man who convinced the Plaza Hotel in New York City to introduce a beer list to complement their wine list. This was in the 1980s, well before it was as common as it has become in the twenty-first century.

Serving up a Blonde at Diamond Knot in Mukilteo, Washington. (Diamond Knot)

The Finkels, in turn, founded their own brewery in Seattle in 1989. Some of the beers which they and their crew at Pike serve up are 6.5 percent ABV Pike IPA, 5.3 percent Pike Pale, 7 percent Pike XXXXX Extra Stout, 9 percent Monk’s Uncle Tripel, 9.9 percent Pike Old Bawdy Barley Wine, and their annual 5.5 percent Auld Acquaintance Hoppy Holiday Ale.

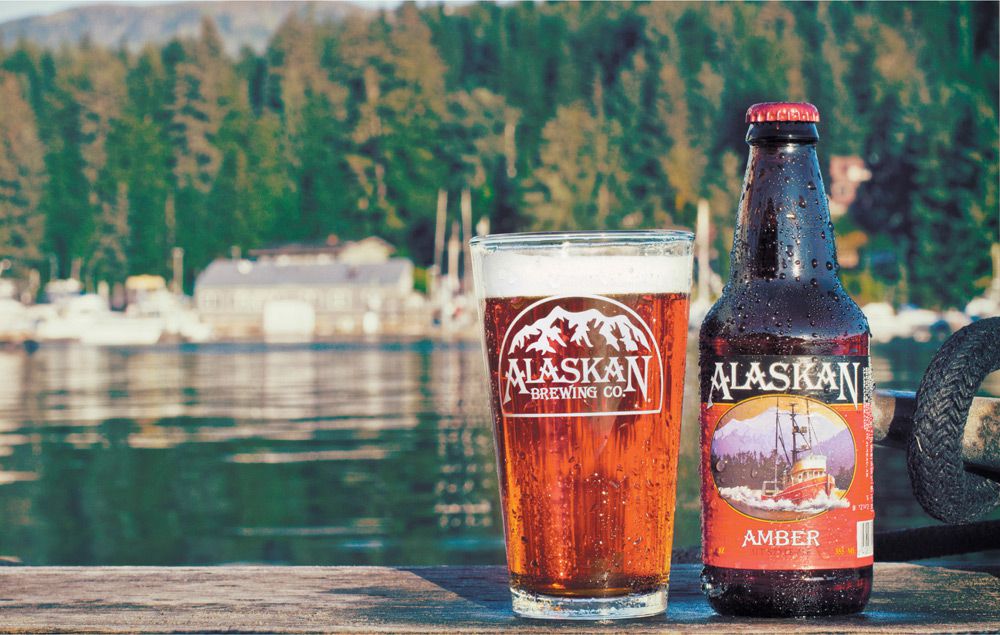

At the extreme corner of the Northwest, Alaskan Brewing in Juneau is still owned and managed by Marcy and Geoff Larson, who founded the brewery in 1986. The long-time flagship, 5.3 percent ABV Alaskan Amber, an alt beer, heads a list that includes 5.3 percent Freeride American Pale Ale, 6.2 percent Alaskan IPA, and limited releases such as 6.4 percent Alaskan Winter Ale and 6.5 percent Alaskan Smoked Porter.

These scenes from Alaskan Brewing of Juneau include founders Geoff and Marcy Larson on the bottle line, and product shots of their limited release 6.5 percent ABV (and 45 IBU) Smoked Porter, launched in 1988, and the flagship 5.3 percent Alaskan Amber. (Alaskan Brewing)

In California, where craft brewing was born with Fritz Maytag, Jack McAuliffe, and Ken Grossman, there are literally dozens of microbreweries and brewpubs from one end of the state to the other. On a drive south from Oregon, one passes through Humboldt County, home to Mad River Brewing in Blue Lake and Lost Coast in Eureka. Mad River was started in 1989 and today brews a variety of beers including its flagship 5.6 percent ABV Steelhead Extra Pale Ale, 6.5 percent Steelhead Scotch Porter, 6.6 percent Steelhead Extra Stout, 8.6 percent Steelhead Double IPA, and 6.5 percent Jamaica Brand Red Ale.

Brewmaster Dylan Schatz with a bottle of his Steelhead Extra Pale Ale. (Mad River Brewing)

Long-time portfolio highlights from the Lost Coast Brewery in Eureka, California. (Lost Coast)

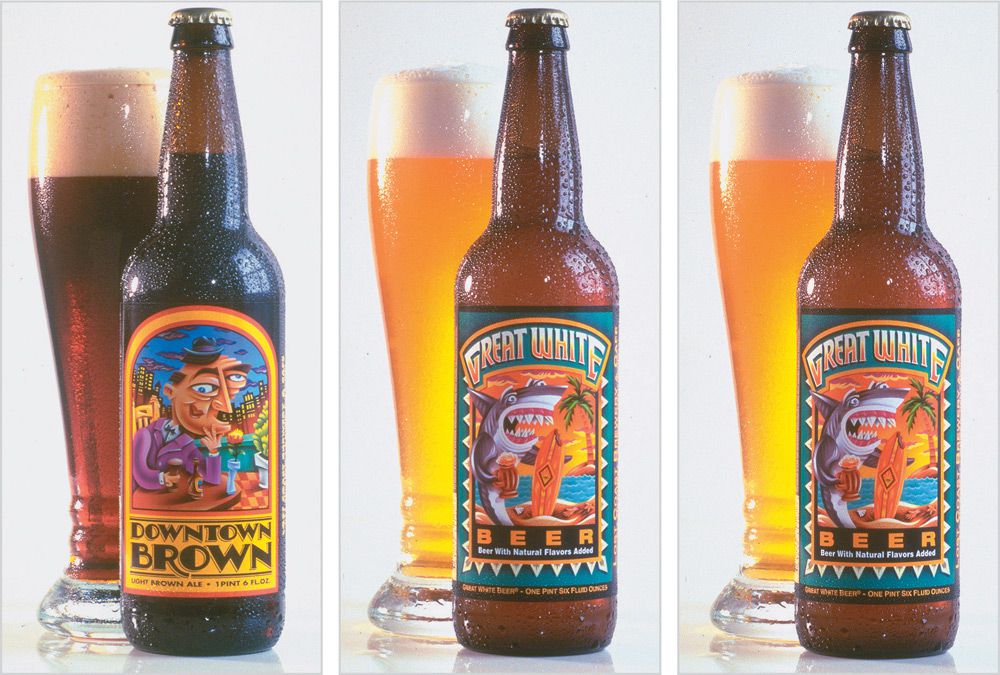

Lost Coast was opened as a brewpub and café in 1990 by homebrewers Barbara Groom and Wendy Pound in the former meeting hall of the Fraternal Order of the Knights of Pythias. The production brewery was moved offsite in 2005. Influenced by British brewing traditions, the portfolio includes 5 percent ABV Downtown Brown, 4.8 percent Great White, and 5.5 percent Alleycat Amber.

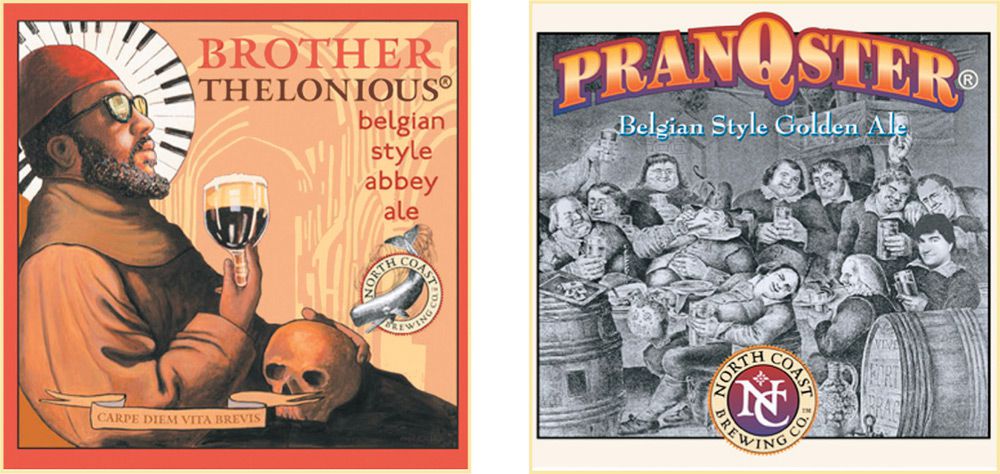

Down the coast in Fort Bragg, one finds North Coast Brewing, which opened in 1988 as a local brewpub. Since that time, brewmaster Mark Ruedrich has transformed North Coast into a major regional brewery with distribution to most of the United States, Europe, and beyond. Among their beers are 9 percent ABV Old Rasputin Imperial Stout, 7.6 percent PranQster Belgian Style Golden Ale, and 9.4 percent Brother Thelonious Belgian Style Abbey Ale. The latter is a reference to jazz pianist and composer Thelonious Monk, and a pun on his surname because abbey beers are associated with monks. North Coast, meanwhile, is a major sponsor of the Monterey Jazz Festival, SFJazz, the Mendocino Music Festival, and the Oregon Jazz Party.

North Coast’s 7.9 percent Le Merle, a rustic Belgian-style saison took a gold medal at the Brussels Beer Challenge in 2012.

Brother Thelonious and PranQster, two Belgian-style ales from North Coast Brewing of Fort Bragg, California. (North Coast)

Pouring pints at Karl Strauss Brewing in San Diego. (Karl Strauss)

Were the beer traveler to begin the trek at the opposite end of California, the first stop would naturally be San Diego, which has developed a beer culture to rival those of San Francisco and the Pacific Northwest. One of the earliest fixtures on the San Diego craft brewing scene was Karl Strauss Brewing, founded in 1989 as a brewery and German restaurant by Chris Cramer, Matt Rattner, and Cramer’s cousin, Karl Strauss, who had spent 44 years with Pabst. A decade later, they expanded, with a large production brewery in Pacific Beach and other brewery restaurants across San Diego County and beyond. They now operate restaurants at the international airports of both San Diego and Los Angeles as well as at the Universal Studios “Citywalk” entertainment district.

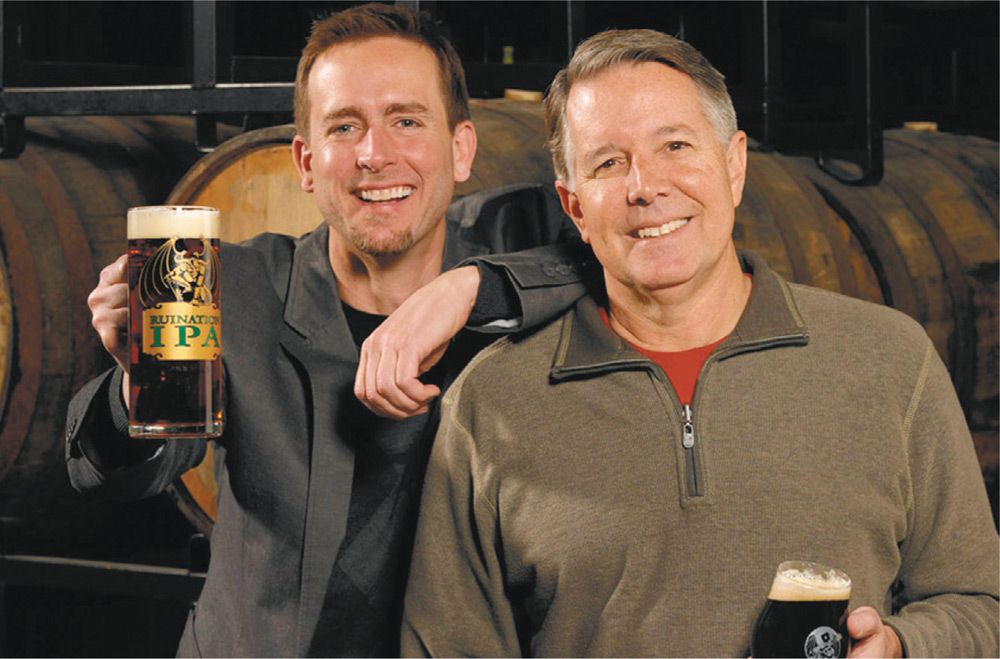

Greg Koch and Steve Wagner, founders of San Diego’s Stone Brewing. (Studio Schulz)

The Karl Strauss lineup of regulars includes 3.3 percent ABV Endless Summer Light, 4.2 percent Karl Strauss Amber, 5.5 percent Pintail Pale Ale, 5.8 percent Red Trolley Ale, 6.5 percent Tower 10 IPA, and 5.1 percent Windansea Wheat. The latter is named for Windansea (not Windandsea) Beach, a legendary San Diego County surfing location.

The high ABV/high IBU lineup at Stone includes the flagship Arrogant Bastard, Double Bastard, IPA, Ruination and Levitation. (Studio Schulz)

Stone Brewing of Escondido in San Diego County owns a box seat on the leading edge of the “edgy” category within the genre of extreme brewing. Founded in 1996, Stone has grown steadily, occupying a seat among the top 20 brewing companies in the United States. In 2011, the readers of Beer Advocate magazine named it as the “All Time Top Brewery on Planet Earth.” Typical of many California brewers in the twenty-first century, Stone’s beers are highly to extremely hopped, frequently in double digit BV percentage, and often aged in oak. Stone is perhaps best known for their 7.2 percent ABV Arrogant Bastard Ale, which is marketed with the arrogant slogan, “Hated by many. Loved by few. You’re not worthy.” Other Stone products include 5.4 percent Stone Pale Ale, 4.4 percent Stone Levitation Ale, 7.2 percent Oaked Arrogant Bastard Ale, and 7.7 percent Stone Ruination IPA.

Chris Cramer and Matt Rattner, founders (with Karl Strauss) of San Diego’s Karl Strauss Brewing. (Karl Strauss)

The Karl Strauss portfolio includes Red Trolley Ale, Tower 20 IPA, and Windansea Wheat. (Karl Strauss)

Other important San Diego County breweries include AleSmith Brewing, started in 1995 by Skip Virgilio and Ted Newcomb, and now owned by brewmaster, Peter Zien; Ballast Point Brewing, founded in 1996 by Jack White and Yuseff Cherney; Green Flash Brewing, started in 2002 by Mike and Lisa Hinkley; and Lost Abbey Brewing, founded in 2006 in a brewery that was previously operated by Stone Brewing.

Half Moon Bay Brewing in Princeton, California. (Bill Yenne photo)

A vintage coaster from Half Moon Bay Brewing. (Author’s collection)

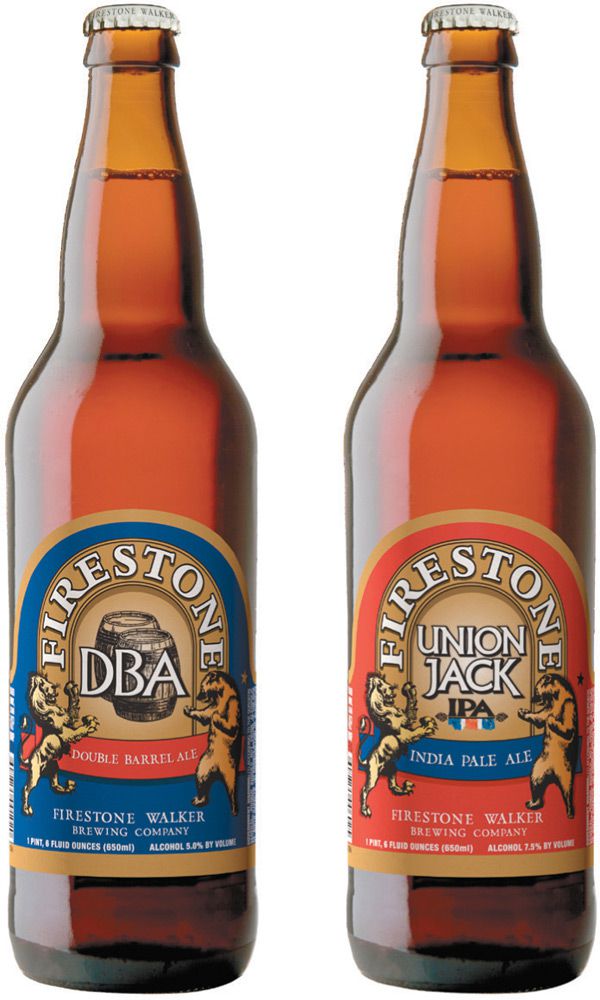

On California’s Central Coast, Firestone Walker Brewing was started in 1996 by brothers-in-law David Walker and Adam Firestone, the son of Brooks Firestone, the owner of Firestone Vineyard. Located in Paso Robles, their brewery “was inspired by the old Burton Union system, once a staple of British beer making. The Burton Union was developed around 1840 as English tastes shifted from London porters to pale ales crafted in Burton-upon-Trent.” Firestone Walker is thought to be the only brewery in the United States to currently employ the “double barrel” union brewing method. Their products include 5 percent ABV Double Barrel Ale and 12 percent Double Double Barrel Ale as well as the critically acclaimed 12.5 percent Abacus barleywine, 9.5 percent Double Jack, 7.5 percent Union Jack IPA, and 8.3 percent Wooky Jack. Their 13 percent Parabola imperial stout ranks in the Beer Advocate top ten worldwide.

Double Barrel Ale and Union Jack IPA from Firestone Walker Brewing. (Firestone Walker)

Farther up the coast, a favorite of this author is the Half Moon Bay Brewing brewpub in Princeton-By-The-Sea, an unincorporated village just north of the town of Half Moon Bay, which is adjacent to the well-known Mavericks surfing location. Founded in 2000, they have always offered 4.8 percent ABV Mavericks Amber Ale as their flagship beer, and today, the entire lineup bears the Mavericks name. Other beers include 4.8 percent Mavericks Big Break Golden Ale, and 4 percent Mavericks Bootlegger’s Brown Ale.

In a list headed by the city’s well-established Anchor Brewing, San Francisco is home to well over a dozen brewpubs and microbreweries of varying sizes and has seen at least that many come and go since Allan Paul started San Francisco’s first brewery since Prohibition back at the dawn of craft brewing. Some of the early names included the Twenty Tank Brewery. Gordon Biersch opened one of their earliest brewery restaurants here in 1992 but closed it in 2012. This left Thirsty Bear Brewing, a brewery restaurant specializing in Spanish cuisine that opened in 1996, as the city’s oldest brewery restaurant.

The Beach Chalet Brewery was established in 1997 by Gar and Lara Truppelli and Timon Malloy in a 1925 Spanish Colonial Revival–style restaurant building overlooking the Pacific Ocean at the western end of San Francisco’s Golden Gate Park.

Also in 1997, on Haight Street at the opposite end of Golden Gate Park, a passionate university-trained brewer named Dave McLean opened his Magnolia Gastropub & Brewery. McLean opened a second gastropub in the Dogpatch neighborhood in 2014. He writes that his pub “marries a Slow Food-like respect for tradition with a Grateful Dead-esque approach to inspired creativity.” The choices at McLean’s gastropubs vary widely, but 4.8 percent Kalifornia Kölsch, 4.8 percent Cole Porter, 7.2 percent Proving Ground IPA, and 10.2 percent Magnolia Old Thunderpussy Barleywine are typically offered.

Shaun O’Sullivan of the 21st Amendment Brewery and Richard Brewer-Hay of the Elizabeth Street Brewery. (Bill Yenne photo)

Speakeasy Ales & Lagers was founded in 1997, not as a brewpub, as were so many San Francisco breweries of its era, but as a production brewery. Nevertheless, they do have a taproom and host frequent Friday night parties. Speakeasy beers, branded with the iconography of the Prohibition era, are widely available in California and other states. Their beers include 6.1 percent ABV Prohibition Ale, 6.5 percent Big Daddy IPA, 9.5 percent Double Daddy Double IPA, 5.5 percent Scarlett Red Rye, and 8 percent Butchertown Black Ale.

Dave McLean’s Magnolia Gastropub & Brewery on San Francisco’s Haight Street. (Bill Yenne photo)

Across town, another San Francisco brewery celebrates the constitutional amendment that ended Prohibition. The 21st Amendment Brewery, best known locally as “21A,” was started in 2000 by Nico Freccia and Shaun O’Sullivan, a veteran of Berkeley’s Triple Rock Brewery. The brewpub is located only two blocks from the major league ballpark that is home to the San Francisco Giants, though brewing and canning for outside distribution takes place at Cold Spring Brewing in Cold Spring, Minnesota. O’Sullivan’s popular portfolio includes 8 percent ABV 21st Amendment IPA, 6.8 percent Back In Black black ale, and the popular 4.9 percent Hell Or High Watermelon Wheat Beer.

The lineup includes the flagship Racer 5 IPA, Red Rocket Ale, Hop Rod Rye IPA, Big Bear Black Stout and Café Racer 15, with IBUs in excess of 100. (Bear Republic)

Also available recently was 8.5 percent Imperial Jack ESB, created by Richard Brewer-Hay at San Francisco’s Elizabeth Street Brewery. The story of the latter beer is one of those remarkable tales from brewing lore that begs retelling. Richard had been brewing an ESB named “Grandpa Jack” in honor of his late grandfather, Jack Newbould, when he and O’Sullivan decided to collaborate on a stronger version at the 21A brewery, renaming it “Imperial Jack.” As they explain, “in 2010, we entered it in the international World Beer Cup competition, and it won a gold medal in the Other Strong Ale category.” They later traveled to London, where they brewed Imperial Jack with Angelo Scarnera, the head brewer at Brew Wharf. They describe this as “an amazing event for both of us, the chance to brew this beer in London. The idea of bringing the Imperial Jack recipe back to England where Richard's grandfather spent his life was a real emotional journey for Richard, one that will be cherished for a lifetime.”

North of San Francisco, in Sonoma County, there is a concentration of some of the most well-known breweries in the United States.

A look inside Bear Republic Brewing of Cloverdale, California. Above is Richard G. Norgrove, the co-owner and brewmaster; while metal meets the oak in the Bear Republic cellar on the opposite top. (Bill Yenne photos, both)

Bear Republic Brewing was founded in 1995 by brewmaster Richard G. Norgrove and his father, Richard R. Norgrove, who serves as the company’s CEO and master of sales and marketing. Many of the brewery’s products bear references to Richard G.’s ongoing second life as a stock car driver, which has become part of Bear Republic’s image. When this author visited him at the brewery, he pointed out a car door, battle damaged in a recent race, that was going to be displayed on the wall of one of the brewery’s retail accounts in New York City. Bear Republic operates a production brewery in Calistoga as well as their original brewery and restaurant in Healdsburg, where smaller, experimental brews are carried out. The flagship beer is 7 percent ABV Racer 5 IPA. Other products include 6.8 percent Red Rocket Ale, “a bastardized Scottish style red ale that traces its origins to our homebrew roots,” as well as 8 percent Hop Rod Rye IPA, 8.1 percent Big Bear Black Stout and 9.75 percent Café Racer 15, a double IPA with IBUs in excess of 100. In Healdsburg, cask-contained ales are being aged, and experimental lambic-type beers are being made using spontaneously-fermenting Brettanomyces yeast species indigenous to Sonoma County.

Lagunitas brewmaster Jeremy Marshall in the Petaluma brewhouse with Mary Bauer, head brewer at the Lagunitas Chicago brewery. (Bill Yenne photo)

The flagship Lagunitas IPA and the seasonal Little Sumpin’ Wild. (Lagunitas)

Lagunitas Brewing was started in 1993 by homebrewer Tony Magee in Lagunitas, but the popularity of the beers dictated a move to a location in nearby Petaluma with freeway access for the trucks. One of the fastest-growing craft breweries in the United States, their output quadrupled between 2004 and 2010, catapulting it into the top ten of American brewing companies. With capacity topped out in Petaluma, a second brewery in Chicago, with a 600,000 barrel capacity, was opened in 2014. The best-selling IPA in a state where IPA is the de facto national beer style is the brewery’s 6.2 percent Lagunitas IPA, the flagship beer. This is complemented by 8.2 percent Maximus IPA, a “bigger” IPA with 70 IBUs, and 8 percent Hop Stoopid, a double IPA with over 100 IBUs that is made with hop extract and oils rather than hop flowers. Also produced outside the IPA family are 6 percent Lagunitas Pils, 9.99 percent Brown Shugga, and 7.5 percent Little Sumpin’ Sumpin’ Ale, with “Millie,” the iconic, but imaginary, spokesmodel on the label. A higher gravity seasonal variation on the latter is 8.8 percent Little Sumpin’ Wild, made with Westmalle Trappist yeast.

The Little Sumpin’ spokesmodel on the brew kettle window. (Bill Yenne photo)

At Russian River Brewing, two people who grew up in the California Central Valley wine industry bought a brewery from a winery and came to brew what are recognized by critics and consumers as some of the world’s greatest beers. Vinnie Cilurzo and his wife Natalie came to Sonoma County in 1997, when Vinnie left his Blind Pig Brewing Company in Temecula to come to work at Russian River when it was owned by Korbel Champagne Cellars. In 2003, Korbel left the beer business and sold the brewery to the Cilurzos. Today, they maintain a brewpub in downtown Santa Rosa, as well as a production brewery where they produce their beer for a growing circle of retail accounts in the West and as far east as Pennsylvania.

Ranks of fermenters that are part of the 600,000-barrel capacity at Lagunitas Brewing in Petaluma, California. Annual output here quadrupled in the first decade of the twenty-first century. (Bill Yenne photo)

Accounting for more than half of their production, the flagship brand is 8 percent ABV Pliny the Elder, a double IPA named for the ancient Roman historian who discussed hops in his early encyclopedia of natural history. Hops are important to Vinnie Cilurzo. They play a key role in finely balancing everything that he brews, even the handful of beers on his list that are less than 6 percent ABV. One might say that he has forgotten more about hops than most of us will ever know, except that one doubts he has forgotten anything.

Inside the brewhouse at the Russian River Brewing Company’s main production site on the outskirts of Santa Rosa, California. (Bill Yenne photo)

The nephew of the beer named for Pliny the Elder is named for the historian’s actual nephew. Pliny the Younger is a 10.5 percent triple IPA which, along with its uncle, shares a place on most lists among the best half dozen or so beers in the world. While the Elder is widely available, the Younger is so rare as to have global cult following. Released for just two weeks each February, it is available only at the Brewpub and at select accounts in California. The lines rival those at a Hollywood premier. A 2013 report from the Sonoma County Economic Development Board devoted three pages solely to the $2.36 million economic impact of the two-week release of Pliny the Younger. Other Russian River beers include 6.1 recent Blind Pig IPA, 7 percent Damnation golden ale, and a long list of barrel-aged beers fermented with Brettanomyces, including 5.5 percent Beatification and 7 percent Supplication, aged 12 months with sour cherries.

Major Russian River brands include the flagship Pliny the Elder, as well as the barrel-aged Sanctification, Supplication, and Temptation. (Russian River)

Across the Pacific in Hawaii, the American brewing tradition goes back to the Honolulu Brewing Company, started in 1898, and the Hawaii Brewing Company (also in Honolulu) that was formed in 1934. The latter became famous for its Primo brand that dominated the Hawaiian market until Schlitz bought the company in 1964. Primo faded quickly when Schlitz moved production to the mainland in the 1970s, and the brand disappeared for decades before being revived in 2007. Breweries operating in Hawaii today include the Aloha Beer Company in Honolulu, Hawaii Nui Brewing in Hilo, and Maui Brewing in Lahaina.

Natalie and Vinnie Cilurzo, owners of the Russian River Brewing Company, enjoy glasses of Pliny the Elder while his cousins age in the background. The prior photo shows the racks of aging barrels. (Bill Yenne photos)

The largest and best known craft brewing company in Hawaii is Kona Brewing on the Big Island of Hawaii. Started in 1994 by the father and son team of Cameron Healy and Spoon Khalsa, Kona’s first bottling was in February 1995. In 2010, Kona joined with Widmer and Redhook as part of the Craft Brew Alliance, which gave Kona access to their production facilities to brew its beers for the mainland market. Kona’s flagship beers are 4.6 percent ABV Longboard Island Lager, 4.4 percent Big Wave Golden Ale, and 5.9 percent Fire Rock Pale Ale. Kona also produces seasonal brands, including 5.5 percent Koko Brown Ale, and beers such 5.6 percent Lavaman Red, which are available only in Hawaii.

Kona Brewing Company, based in Kailua-Kona on Hawaii’s Big Island, is the largest brewery in the state.

Inside Kauai Island’s brewpub. (Kauai Island)

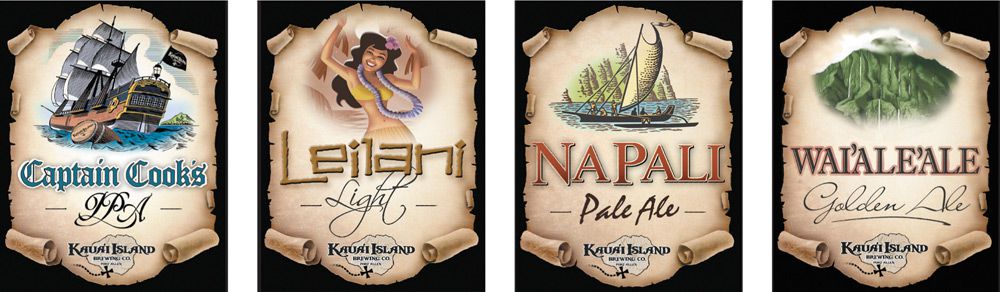

At the opposite end of the Hawaiian archipelago, in Port Allen on the island of Kauai, is “The World’s Westernmost Brewery.” As they say at Kauai Island Brewing, their beer is the “last beer before tomorrow.” Indeed, for the beer traveler, this is the end of the line. There are no breweries on earth between here and the International Dateline. The previous westernmost brewery was Waimea Brewing, was about a half-dozen miles farther west. When the lease was up at this location in 2011, owners Bret and Janice Larson, along with their brewmaster Dave Curry and his wife Christina, decided to come together and become co-owners of Kauai Island, which opened as a brewpub in 2012.

Longboard and Pipeline are two of their leading brands. (Kona)

The beers which Dave Curry has brewed for the travelers who come here to watch the sunset at the last frontier of the world of beer include 5.4 percent ABV Na Pali Pale Ale, 4.3 percent Pakala Porter, 3.8 percent South Pacific Brown, 4.3 percent Leilani Light, 6.3 percent Cane Fire Red, and 4.8 percent Wai’ale’ale Ale, a beer with a tongue-in-cheek-twisting name that pays homage to Kauai’s Mount Wai’ale’ale, the alleged wettest place on earth. Travelers will enjoy the 5.5 percent Captain Cook’s IPA, named for a fellow traveler from the tall ship era who “discovered” Hawaii. Indeed, his first landfall in Hawaii was only eight miles from the brewery’s location. As Curry writes, “Created after the hoppy ales brewed in the 1700s for the long journey from England to Hawaii, this Ale is one of our hoppiest beers ever [67 IBUs] using 15 pounds of hops for 155 gallons of beer.” Grab one and join me outside for the sunset, there’s a tall ship on the horizon.

The Kauai Island brewhouse. (Bill Yenne photo)

Bret Larson and Dave Curry of the Kauai Island Brewing Company enjoy a round at their pub in Port Allen on the island’s south shore. It is the westernmost brewery in the world. (Kauai Island)

This selection from the Kauai Island portfolio includes Captain Cook’s IPA, Leilani Light, Napali Pale Ale, and Wai’ale’ale Ale. (Kauai Island)