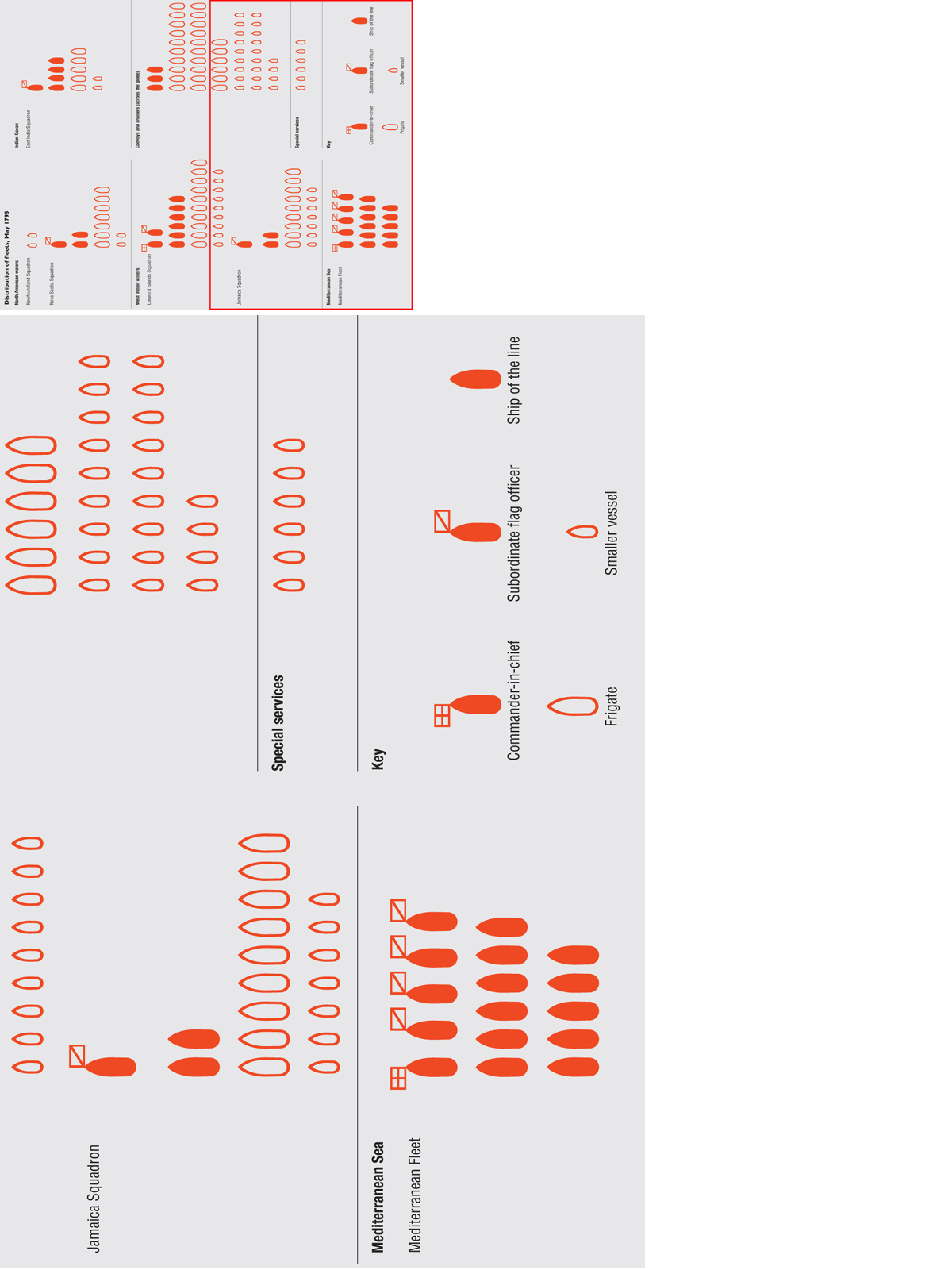

The highest form of operational organization in the Navy was the fleet. Under normal circumstances, a fleet was formed into a single line before action commenced, and in some instances broke apart in the course of the fighting into duels between individual ships. For this reason a subordinate admiral, whether in command of a division or a squadron, did not play a vital role in combat. He was advised by Admiralty instructions to ‘be particularly attentive in observing that a ship which carries his flag, and all the squadrons and divisions under his orders, preserve very correctly their station in whatever line or order of sailing the fleet may be formed’.

The manner in which an admiral divided his fleet lay entirely at his own discretion, though he generally apportioned at least ten of his ships of the line to a squadron. These could then be sub-divided into divisions while at sea or to function in this form in battle.

Squadrons were approximately of equal strength, with those at Trafalgar being 13 and 14 ships, respectively. In 1807, Admiral Gambier had three equal squadrons of ten ships, with each squadron divided into two divisions, under a rear-admiral or commodore. While cruising, fleets did not usually organize themselves according to the line of battle that they assumed when in the presence of the enemy. They might cruise in two parallel lines of approximately equal strength, a mile or more apart, with each line’s vessels sailing bow to stern with two or three cables (a cable being 100 fathoms, or 200 yards) between them, or in line abreast, with ships sailing on parallel courses. In order to maintain communications between the various divisions, frigates were positioned at various points around the fleet and lookouts kept aloft at their stations.

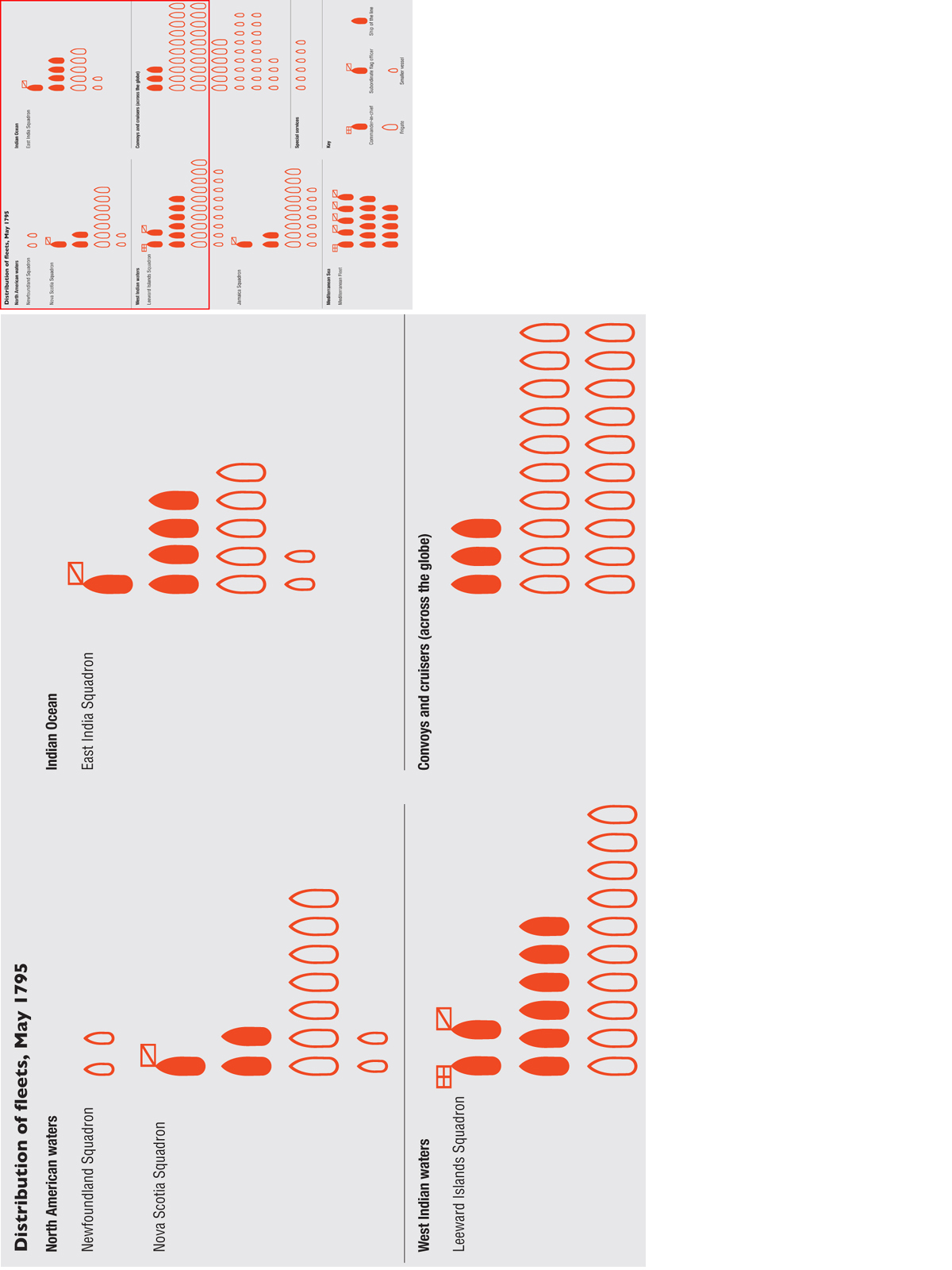

The vast majority of ships in the Royal Navy were assigned to one of the main fleets, which were distributed around the world. Some vessels served exclusively on convoy duty, while others, on individual missions from the Admiralty, were not attached to a particular fleet. Each fleet was led by a commander-in-chief – always a very senior admiral. While some squadrons were formed for specific purposes and often bore the names of their commanders, fleets were normally assigned to a particular stretch of ocean – a sort of geographical area of responsibility. The actual area covered was not always perfectly defined, so that, for instance, the Mediterranean Fleet served as far as the coast of Portugal, while the Channel Fleet cruised well into the Bay of Biscay as far as the northern coast of Spain. Needless to say, the strengths of the various fleets varied according to the relative importance of their roles and responsibilities. Thus, the Channel Fleet, whose principal function was to defend the southern coast of England and whose secondary role was to blockade Brest, was invariably maintained on a strong footing, whereas the West Indian fleets were generally scaled down once the French were driven from the Caribbean. The Newfoundland and Nova Scotia fleets were nearly always small, with little to do until war broke out with the United States in June 1812. In all, there were seven or eight main fleets with titles based on their respective geographical areas, in addition to numerous single ships and detached or independent squadrons, usually composed of frigates and smaller craft.

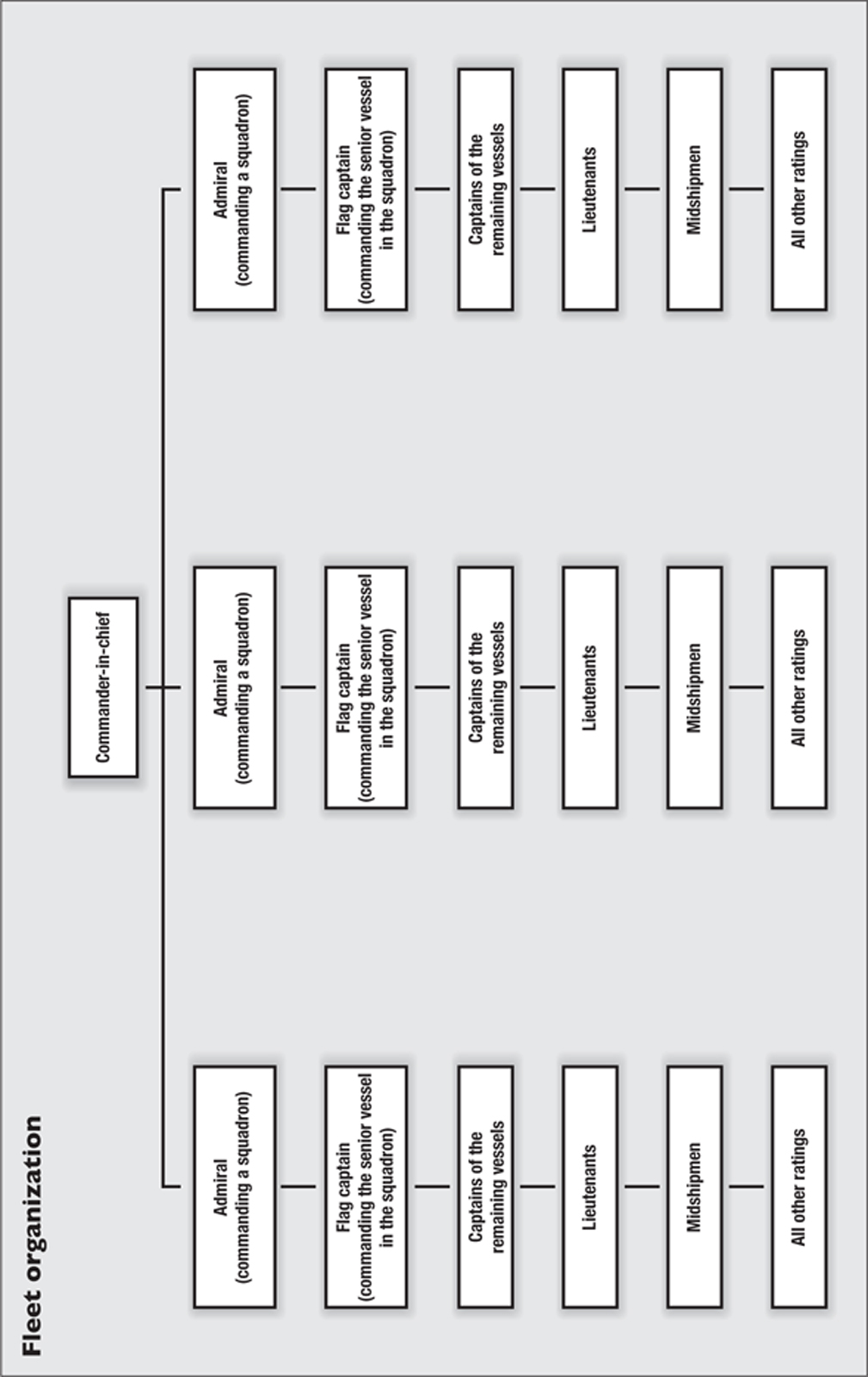

The primary function of the sailing warship, which was defined by the number of guns she carried, was to engage the enemy. Guns, today commonly referred to as ‘cannon’ but more correctly as ‘great’ or ‘long’ guns, were simply weapons consisting of an iron tube, without rifling, mounted on a heavy carriage with four small wooden wheels on fixed axles. A gunner could raise or lower the elevation of his weapon by +10 degrees or –5 degrees by inserting or removing a quoin, or wooden wedge. The carriage itself could be aimed to a limited extent by pulling on the gun tackles – a series of ropes fastened to the sides of the carriage and secured to the deck. Handspikes and crowbars were also employed in manhandling the gun into the desired position. Every gun was commanded by a ‘gun captain’ whose men varied in number according to the size of the gun. If a ship were firing from one side alone, the crew from the unengaged side would assist the men on the opposite side of the gun deck, so increasing the rapidity of fire. (Royal Naval Museum)

This shows the number of vessels assigned to the fleets, though the actual strength in situ could vary. Note that the Channel and North Seas fleets are not shown.

Given the sheer size of the Royal Navy it is easy to assume that the defence of the nation could be taken for granted. In reality, Britain’s naval requirements demanded the presence of its fleets across the world’s oceans, and hence the Channel, though well defended, was patrolled by only a fraction of the Navy’s resources.

All fleets were divided into divisions or squadrons, usually led by vice- or rear-admirals or commodores, with fleet commands normally held only by full admirals. Every ship was commanded by a captain, themselves supported by lieutenants and midshipmen.

The Channel Fleet served as the principal arm of the nation’s defence. It not only cruised the waterway between Britain and the Continent in order to prevent invasion, but kept constant watch over the French ports of Brest, Le Havre, Cherbourg, Lorient, Rochefort and others, engaging whenever possible vessels which ventured out. Brest was the principal enemy port in this area, but where sufficient numbers of ships were available the Channel Fleet could blockade the other French ports, as well as Ferrol on the north-west coast of Spain. In 1804, the fleet was to have 20 ships of the line to serve off Brest, with another seven off Rochefort, seven others off Ferrol and three more off the Portuguese and Spanish coasts. This ensured that no enemy could venture past Gibraltar without detection. The main bases of the Channel Fleet were Portsmouth and Plymouth, and it used the anchorages at Spithead, St Helens and elsewhere on the south coast of England.

In 1795 the Channel Fleet consisted of 26 ships of the line, plus 17 frigates. In 1800 it had three first rates, 11 second rates and 33 other ships of the line. With its frigates and other vessels it numbered in total 72 ships and smaller craft. In 1805 it numbered 35 ships of the line and 16 frigates, but by 1812 it was down to just 15 ships of the line, 14 frigates and ten other smaller vessels. Since the Brest Fleet was not present at Trafalgar it was never destroyed, and hence the strength of the Channel Fleet necessarily remained high. It fought one large action, at the First of June 1794, but notwithstanding French losses of six ships the remainder of the opposing fleet reached Brest and thereafter had to be continuously watched.

Based principally at Cork, in southern Ireland, the Irish Squadron existed to protect trade moving westwards across the Atlantic, as well as to defend Ireland from invasion, though its smaller numbers obliged it to depend on assistance from the Channel Fleet as circumstances required. In 1797 the squadron had 16 ships, only one of which was a line of battle ship, the others being frigates and sloops. This force was reduced two years later to 12 ships. In 1805 it had 23 ships, of which 12 were frigates and eight were sloops. In 1812, with naval supremacy achieved, the Irish Squadron consisted of only 13 ships, with no complement of line of battle ships.

The second most important major home command was the North Sea Fleet, whose name is slightly misleading since part of its area of responsibility extended into the Channel as far as the Dutch and Belgian coasts. In 1797 it numbered 56 ships, including 20 of the line. It was with this fleet that Admiral Duncan fought and won the battle of Camperdown in that year. Attached to the North Sea Fleet was the Downs Squadron, which protected the entrance to the Channel. When war began in 1803 this squadron and others were combined into a single fleet, which two years later, in the year of Trafalgar, reached a strength of 80 ships, including 11 of the line and 20 frigates, the whole divided into five squadrons, with responsibilities for blockading the French port of Boulogne, and the Texel and the Scheldt, the main entrances to the Dutch ports. The strength of the fleet fluctuated greatly over the years, with 34 ships in the Downs Squadron in 1807, of which one was a ship of the line. Eight vessels were based at Yarmouth, but none larger than a sloop; seven small vessels hailed from Sheerness; and 15 from Leith. In 1812, the Downs Squadron had 31 ships, but none of the line or frigates. At Yarmouth there were eight ships, half of them sloops. The force watching the Texel and the Scheldt had 53 ships, of which 27 were of the line, five frigates and 12 sloops. Fourteen ships, including two frigates and four sloops, were based at Leith.

As in the British Army, where a certain flexibility enabled the number of brigades composing a division to vary according to circumstances, the same principle applied in the Royal Navy, in which a fleet could consist of a fluctuating number of vessels depending on the resources available, the nature of the task to be fulfilled, detachments made for auxiliary operations or the acquisition of supplies, and other factors. Nor did a fleet necessarily operate as single, consolidated force. The vast expanse patrolled by the Channel Fleet required its commander to allocate a proportion of his vessels to blockade duty while the bulk of his ships of the line remained either in port or at sea, ready to confront a rival fleet when required. Similarly, whereas at Trafalgar Nelson assembled virtually the whole of the Mediterranean Fleet, his force at the Nile seven years earlier had comprised only a squadron from the same fleet (then under St Vincent), though naval historiography, both contemporary and modern, often refers to his ‘fleet’.

While important in British naval strategy, the Baltic Fleet was not always on station in great numbers, but rather was augmented as circumstances required. This was particularly true in 1801, when formation of the League of Armed Neutrality involving Denmark, Sweden and Russia led the Admiralty to dispatch a powerful fleet under Sir Hyde Parker, with Nelson as second in command. The fleet consisted of 21 ships of the line, 11 frigates and ships of 50 guns, plus a large armada of gunboats, brigs, cutters, schooners and luggers. In fact, it was more of a fleet assigned a special mission than a permanent fixture with a geographical designation. It was with this fleet that Nelson won the battle of Copenhagen.

The Baltic Fleet again assumed importance in 1807, when Admiral Gambier was dispatched with a fleet of 17 ships of the line to force the Danes into surrendering their ships in the wake of the accommodation between France and Russia in July. In the following year a permanent Baltic Fleet was established in reply to the French establishment of the Continental System and the belligerence of Denmark following Gambier’s seizure of its fleet. In 1812 the Baltic Fleet numbered 39 ships, including ten of the line, six frigates and 14 sloops.

The Mediterranean Fleet, second only in importance to the Channel Fleet, was a vital component of the Royal Navy, for the Mediterranean held important British strategic interests. The fleet was always led by a senior and experienced admiral whose primary responsibility lay in maintaining a close blockade on the principal French port, Toulon, and the Spanish port of Cadiz. This fleet fought off the Hyères Islands in 1795, and in three other battles of much greater significance – Cape St Vincent in 1797, the Nile in 1798 and Trafalgar in 1805. Like the other geographical commands, the fleet designated for service in the Mediterranean did not always confine itself to what ought to have been a clearly defined area. Thus, St Vincent and Trafalgar were fought west of Gibraltar; in the latter case Nelson even chased Admiral Villeneuve across the Atlantic before following him back to European waters. The Mediterranean Fleet varied in strength as circumstances required. In 1795 it had 31 ships, including five first and second rates, 11 third rates, and 11 fifth and sixth rates. In 1797 it surpassed even the strength of the Channel Fleet, with 62 ships, including 23 of the line, 24 frigates and ten sloops. By 1812 – years after the decisive victory at Trafalgar – it was even larger, with 90 ships, consisting of 29 of the line, the same number of frigates, and 26 sloops.

Action between the USS Argus and HMS Pelican, 14 August 1813. The American brig, cruising in British coastal waters, carried out the most destructive cruise of any US warship during the conflict with Britain, taking 19 merchant ships between the English Channel and southern Ireland, an area known as the Western Approaches. The Pelican, observing the burning wreck of one of Argus’s recent triumphs, gave chase, using her carronades to destroy her opponent’s main braces and after running rigging. This rendered Argus unmanageable, thus enabling Pelican to rake the stricken vessel until it struck its colours after 45 minutes’ resistance. (Stratford Archive)

Admirals and captains regarded gunnery more as an art than a science, and hence paid little attention to the study of ballistics. What mattered to them, as well as to warrant officer gunners, was that a gun crew could perform their drill as quickly and as efficiently as possible. Stated simply, once the ship closed with its opponent, rapidity of fire was what mattered most, and with captains encouraged to bring their vessels as close as possible to the enemy, the damage and casualties thus inflicted (and received) were usually severe. (Philip Haythornthwaite)

Whereas during the American Revolutionary War the West Indies had been a very active theatre of naval operations, particularly in the later stages of the conflict, this was not so during the French Revolutionary and Napoleonic Wars, when the French did not maintain a fleet there, particularly after the fall of Martinique. The British naval forces in the Caribbean were divided into two commands, one for Jamaica and the other for the Leeward Islands. The former was based at Port Royal. Its principal function was to combat privateers and provide convoy service in the western Caribbean. When the war began in 1793, the Jamaica Squadron consisted of a 50-gun ship, three 32-gun frigates, four sloops and a schooner. In 1795 there were 19 ships on the station – three ships of the line, two fourth rates, six fifth rates, a sixth rate and three schooners. Two years later the station had 31 ships, including seven of the line, 15 frigates and seven sloops. This was increased by 1805 to 51 ships, including three of the line, 14 frigates and 24 sloops. In 1812, with all of the French West Indian possessions in British hands, the station amounted to only 19 ships, of which one was a ship of the line, eight were frigates and the rest smaller vessels.

The Leeward Islands Squadron was based at Antigua and Barbados, though it could also use Martinique and St Lucia once those French colonies had been captured. At the beginning of the war this force numbered nine ships of the line and 14 smaller ships and vessels, though it was increased within a year by three more ships of the line and seven other vessels, together with a large convoy of troops with which began the campaigns for the capture of the French West Indian possessions. In 1795 the Leeward Islands Squadron consisted of 26 ships, including eight third rates, ten frigates, six sloops and other vessels. In 1797 it numbered 44 ships – nine of the line, 16 frigates and 11 sloops. Thereafter the fleet was gradually decreased as a result of the capture of most of the French colonies. By 1801, just before a short-lived peace was signed at Amiens, the fleet was down to just 26 ships and vessels, including one of the line, nine frigates, seven sloops and other craft.

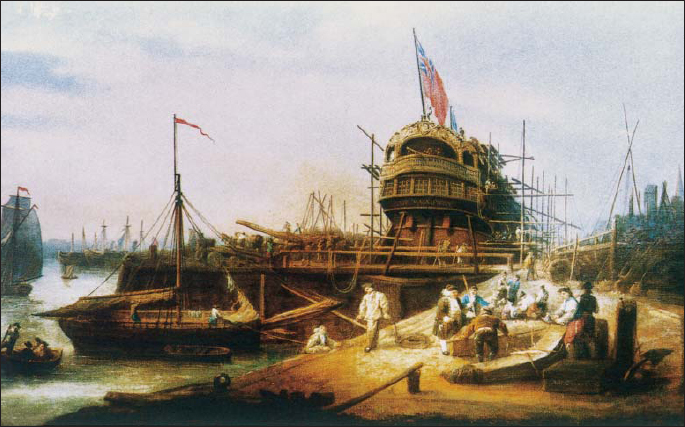

Launching a ship of the line. Ships of this size took years to construct, either in the Royal dockyards or in private yards. Much remains to be done to the ship depicted here, which must now be ‘fitted out’ with three vertical masts and a bowsprit, together with all the yards, booms, and gaffs to which sails will eventually be attached. Fully fitted ships were festooned with miles of rigging – all the ropes, cables and chains used to support the masts and spars and to raise, lower and adjust sails and yards – together with the tackle – pulley blocks, eyebolts and other apparatus used to hold or adjust them. After the rigging came all the ancillary equipment, including the rudder and wheel, anchors and their cables, capstans, the ship’s boats, the galley stove, pumps and other equipment. The ship’s armament was also added, together with the tools and tackle associated with it. The interior of the ship had also to be finished, including the cabins and quarters, galley, magazine and store rooms. Once complete, the ship was formally commissioned, at which point all her stores were added and a crew assembled to man her. (Royal Naval Museum)

As the settlement at Amiens restored most French possessions, when war resumed in 1803 the fleet in the West Indies had to be increased so as to enable it to capture these islands all over again. In 1805 it numbered six of the line, 13 frigates and the same number of sloops, but by 1812 it had again been reduced, owing to the fact that by 1810 all the colonies of France and her allies had been retaken. Royal Navy warships in the West Indies totalled 27, including one of the line, five frigates and 13 sloops.

Two squadrons were maintained off the American coast, with bases at Halifax, Nova Scotia, and at Newfoundland. These were considered minor areas of responsibility, for the United States remained neutral until 1812. When war with France began in 1793, the Halifax Squadron had only four ships and vessels, none of which exceeded 32 guns; the Newfoundland Squadron had one 64-gun ship, three frigates and five sloops. Nor did Royal Navy strength grow by an appreciable degree: five ships in 1797, seven two years later, 13 in 1805, and 12 in 1812. In 1795, the Halifax Squadron had ten ships, of which three were third rates. In 1800 this rose to 13, including two third rates. The number fell five years later to only eight ships, none of which were larger than frigates. As a result of the war with the United States, however, the waters along the American and Canadian coasts grew in importance, and by the late summer of 1812 the station had 25 ships, including one of the line, eight frigates and seven sloops. This increased again by the following year, when the North American station numbered 60 ships, including 11 third rates, 16 fifth rates and 25 sloops.

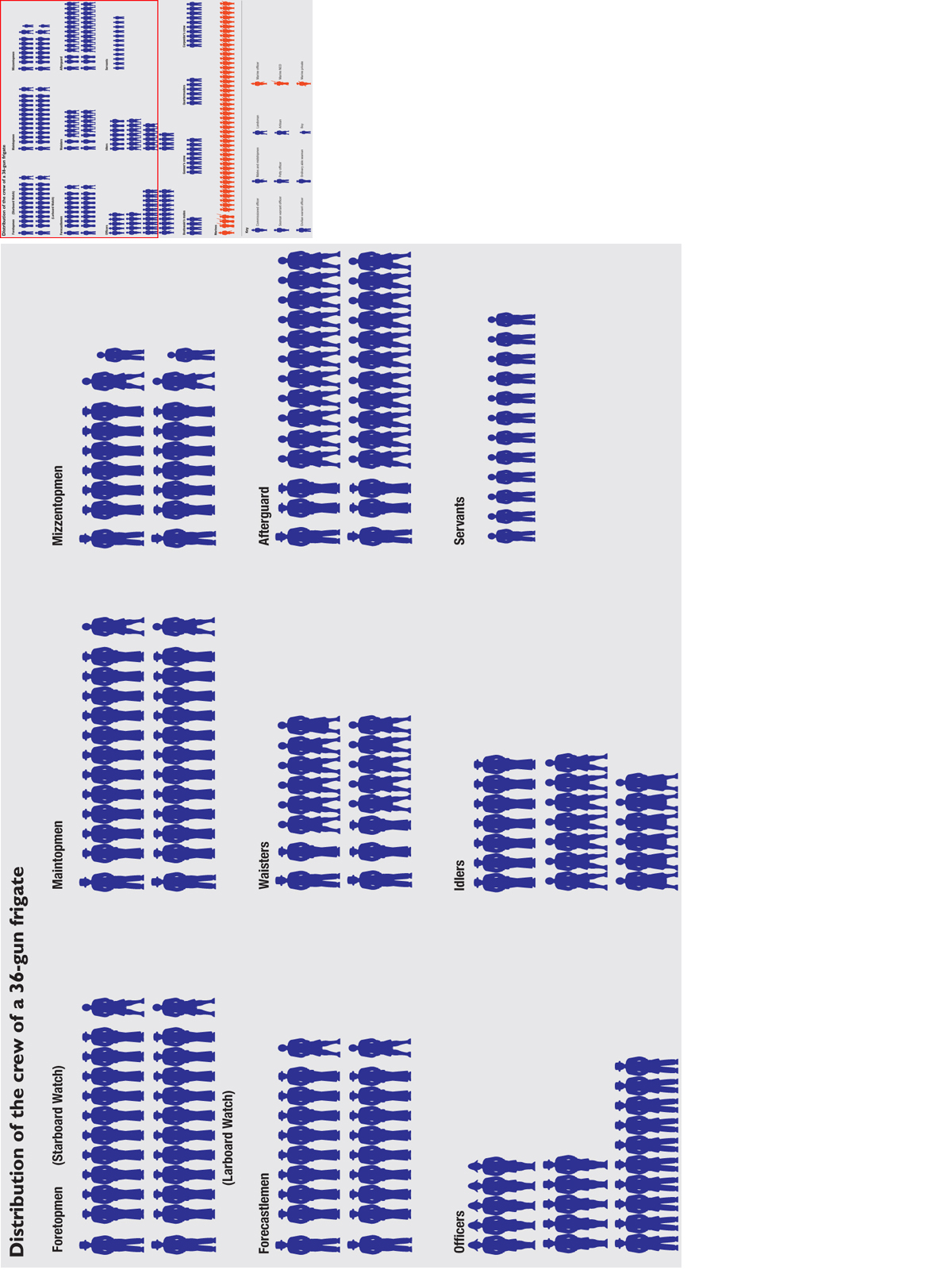

Every man on a ship was assigned a station based on aptitude, fitness, training and experience.

Ships assigned to these stations carried out raids in the East Indies and protected merchantmen in convoys bound for Europe. The East India Squadron in particular mostly protected trade originating from India. In the first year of the war it numbered 13 ships, including five third rates. By 1797 it had 32 ships, including ten of the line, 17 frigates and four sloops. Two years later this number had declined to 17, rising again to 23, including 17 of the line, by 1803. In 1805 it numbered 29 ships, including eight of the line. In 1812 the fleet was 24 ships strong, including one of the line.

No vessel could operate properly without an adequate system for the organization of its crew. Ships often carried considerable numbers of men, who could not be expected to perform usefully as a single entity. A first rate, for instance, contained over 800 men, and the larger frigates over 300, with some proportion being unwilling occupants, while others were unable to read, disaffected or lazy. There were also some affected by illness, tiredness or drunkenness, or who harboured grievances of one sort or another. In the face of all these obstacles, the ship, in all its complexity as something of a small floating village, had to be managed. As the same crew might remain aboard the same vessel – in extremely cramped conditions – year after year, with consequently little in the way of new social contacts, an exceptional degree of discipline and intelligent organization was required to keep the ship running efficiently.

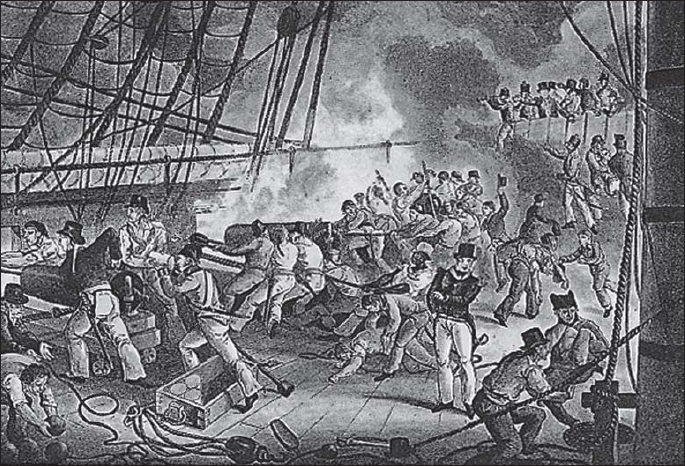

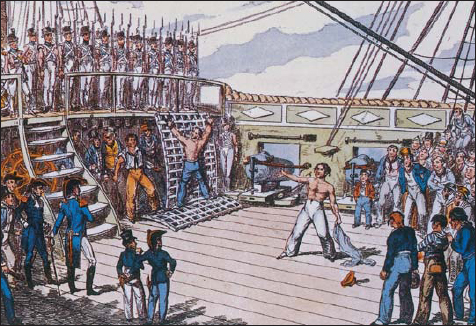

Boarding. In the frenzy of combat firearms could not be reloaded – hence the preference amongst most seamen for edged weapons. The attackers (right), largely armed with cutlasses – apart from the tomahawk-wielding sailor in the foreground – are led by an officer, identifiable by his bicorn hat worn ‘fore-and-aft’; that is, with the peaks to front and rear, as opposed to ‘amidships’, or side-to-side. The defenders (left) favour the pike which, while often effective for repelling boarders, proved a liability if an assailant managed to parry a thrust and skirt past the point of the weapon. (Royal Naval Museum)

The crew was divided into groups and assigned specific tasks, often several at a time depending on the mission of the ship at any given time. A sailor could be assigned to a specific part of the rigging, serve a particular gun during battle, or work the pumps if necessary. When the ship docked or disembarked, he might play some other role, and even this might change – for instance to duties connected with his mess at mealtimes – depending on which watch it happened to be. Whatever his responsibilities, usually assigned to him by the first lieutenant who first considered the man’s aptitude and fitness for the job – and these could be a dozen or two – a seaman was expected to perform them quickly and efficiently.

It was the first lieutenant’s responsibility to ensure that enough men were on duty at any given time so that the ship was safe and functioning well. He normally divided the crew, therefore, into two or three watches. The majority of ships used the two-watch system, which resulted in nearly every man belonging to one or the other, in nearly equal numbers, with the watches known as larboard and starboard. If both watches were on deck, those men assigned to the larboard watch might be responsible for the ropes and line of their side of the ship (the left-hand side as one faces the bow), while those of the starboard watch manned the other side.

Sailors floating on debris. Contrary to popular belief, ships rarely sank in battle; storms and shoals were the principal culprits. When a ship did sink, panic normally ensued, as one sailor described: ‘All hands were now struck with consternation and dismay, and everything was enveloped in uncertainty and gloom. The officers, hoarse by so much exertion of voice, issued their orders hesitatingly, and in vain. Subordination, the first and most important branch in naval discipline, seemed for the time being suspended in every man … In vain did the captain call out for all hands to remain on board till day break, when all would be saved; everyone acted to the best of his own judgement.’ (Philip Haythornthwaite)

Those men who were not a part of one of the watches were known as idlers, the name given to those whose services were needed on a constant basis during the day, and therefore were not expected to keep any of the night watches, unless of course all hands were summoned on deck at night. Idlers constituted about 7 per cent of the crew on a first rate and about 10 per cent on a sixth rate. Idlers included the master at arms and the various corporals, the armourer, sailmaker, cooper and the mates working along with them, the yeoman of the boatswain’s, carpenter’s and gunner’s store rooms. Other idlers included the cook and his assistants, butchers, hairdressers, barbers, tailors, pursers, poulterers, the first lieutenant’s secretary, the purser’s steward and various officers’ servants (not domestic servants – though they did perform menial services from time to time – but rather young officer hopefuls). Some of the marines would fall under the category of idler, as well, plus tailors, shoemakers, painters and bakers.

Apart from the idlers, the rest of the crew were assigned part of the ship for which they were responsible, a designation that gave rise to nicknames which reflected the area in which they carried out their tasks. Thus, the topmen, the most skilled seamen, worked aloft in the masts and amongst the rigging. Ships of the line had three types of topmen, one each for the fore (forwardmost), main (middle) and mizzen (rearmost) masts. Aboard smaller ships, the mizzentopmen formed part of the afterguard, which will be described later. The topmen, maintopmen, foretopmen and mizzentopmen had to be extremely fit and agile, for they had to perform work in the highest masts, sometimes in the face of high winds and rain and a rolling ship. Their numbers varied, but, for instance, aboard the San Domingo, a 74, there were 25 foretopmen, 27 maintopmen and 25 mizzentopmen in each watch. Each group was led by a petty officer, known as the captain of the foretop, mizzentop or maintop, as appropriate.

Owing to their specialist abilities and knowledge, the topmen enjoyed a virtual monopoly on work aloft, with the remainder of the crew rarely permitted (or indeed able) to go into the rigging. The forecastle men worked towards the front of the ship, known as the forecastle (pronounced ‘foc-sul’), and handled, amongst other equipment, the anchors. They were often the oldest and heaviest sailors, since they were depended upon for both skill and strength, not dexterity; nor were they required to act with particular swiftness, like those in the tops. A 36-gun frigate contained about 20 forecastle men, all but perhaps two of whom were petty officers or able seamen, led by a captain of the forecastle for each watch.

The afterguard, which worked on the quarterdeck and poop, was composed of men who almost never went aloft, except perhaps to help furl the mainsail (pronounced ‘mainsul’), and were effectively used for their brute strength, such as for pulling and hauling. Aboard a 36-gun frigate there were about 28 such men, perhaps half a dozen being able seamen, which is to say men possessing more skills than ordinary seamen. The waisters possessed the fewest skills of the men on deck, being composed of the least useful landsmen, whom some of the crew regarded as less than true sailors. Waisters performed the least interesting and most onerous work on the main, or gun, deck and sometimes assisted with the lines and ropes. A 74-gun ship might contain about 30 waisters in each watch.

These six parts of the ship (three types of topmen, forecastle men, afterguard and waisters), accounted for about half the ship’s company, the remainder being officers, marines, boys and servants.

Large and medium-sized ships were also organized into divisions to enable the officers to administer the ship’s company along logical administrative and social lines, as opposed to the system previously described, which concerned their duties only. According to the Admiralty Regulations and Instructions, the captain, aided by his officers, was to:

Divide the ship’s company, exclusive of the marines, into as many divisions as there are lieutenants allowed to the ship; the divisions are to be equal in number to each other, and the men are to be taken equally from the different stations in which they are watched. A lieutenant is to command each division; he is to have under his orders as many master’s mates and midshipmen as the number on board, being equally divided, will admit; he is to sub-divide his division into as many sub-divisions as there are mates and midshipmen fit to command under his orders.

Heaving the line, one of the innumerable tasks performed by sailors in the operation of a ship. Weighing anchor, for instance, required the combined strength of much of a ship’s company, not only to turn the capstan which raised the anchor (of which ships of the line carried several), but to coil the massive cables as they were hoisted aboard. At the same time, much of the remaining crew would be busy setting sail and thereafter make more, or shorten, sail depending on weather conditions and the captain’s instructions. (Stratford Archive)

The division enabled the captain and his officers to monitor the health and welfare of the ship’s company. Proper sanitation aboard the ship was essential in order to ward off sickness and disease, and thus the officers inspected the clothing and bedding of their division, and were responsible for seeing that the men did not swear or get drunk – no simple task. Petty officers and midshipmen kept lists of the men for whom they were responsible within a given division, each list indicating every sailor’s duty and the number of his hammock. When in port, those in charge of a division mustered their men each evening, and conducted inspections for health and cleanliness every Sunday morning.

Midshipmen were usually volunteers, aged between 14 and 18, eager to be commissioned as lieutenants – the first rung on the ladder of promotion in naval service. Some, however, were men promoted from the lower deck, such that midshipmen could be considerably older – up to perhaps 40 – having failed to pass the exam for lieutenant. Once aged 14 or older, a midshipman held the same rank as a petty officer, while younger midshipmen held the equivalent rank of an able seaman.

Midshipmen oversaw the work performed by most of the crew of lesser rank, and kept the watch system, whether two or three, functioning on time. The senior midshipman of the watch stood on the quarterdeck, the second on the forecastle, and the third abaft the mizzen mast. Others, of less experience, answered to their superiors and carried out all manner of tasks such as taking and recording soundings, notifying the officer of the watch of anything of note, and marking the log slate. Using sextants or quadrants, midshipmen would also record the ship’s position at noon, being careful to take this and other pertinent information down in their journals, which the captain would later inspect. Midshipmen oversaw signalling, commanded the boats and worked aloft, situating themselves, according to directions from a lieutenant, in one of the mast tops, where they supervised the furling and reefing of sails.

Each of the ship’s divisions was assigned a midshipman who was responsible for numerous tasks, such as ensuring that the men had clean clothing, that the ill were accounted for on the sick list and reported to the sick bay, and that hammocks were stowed after use. Midshipmen could inflict minor punishments on seamen, usually in the form of blows delivered by a knotted rope. Sailors with years of experience behind them, and sometimes considerably older than a midshipman, had no option but to endure the reprimands and punishments of mere teenagers.

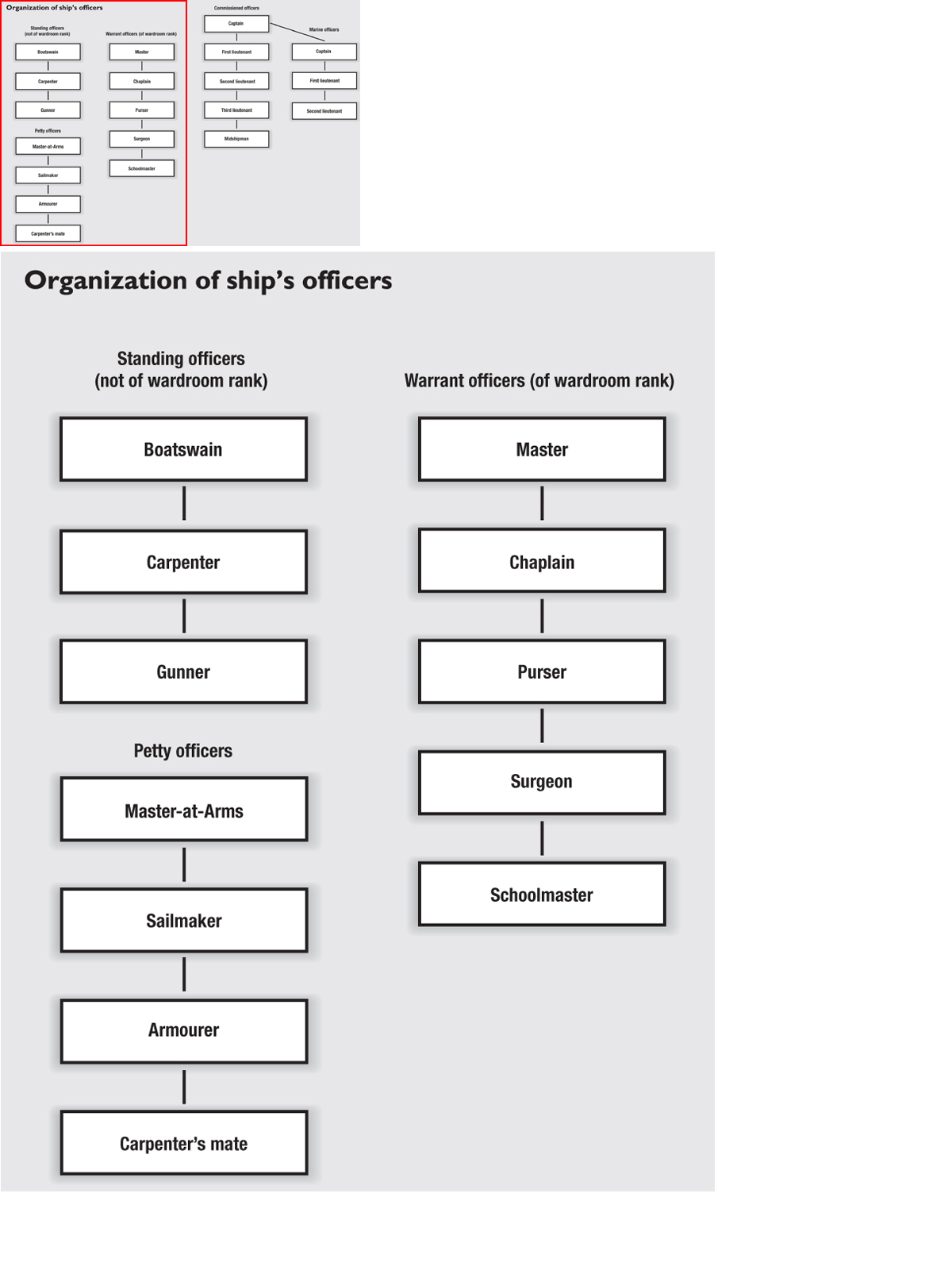

A ship contained four types of officers, the most senior being commissioned officers – the captain and his lieutenants – who were appointed by the Admiralty, with midshipmen training to become lieutenants. Warrant officers were next in importance, and consisted of the master, who was responsible for the navigation of the ship, the chaplain, who performed church services, the purser, who stocked, supplied and managed the ship’s stores, and the surgeon, who served as a physician as well as a surgeon proper. Standing officers – so-called because they remained with their ship even when it was de-commissioned – consisted of the boatswain, who supervised all the work conducted above decks, the gunner, who looked after the ship’s armament on a day-to-day basis and managed the guns during battle, and the carpenter, who cared for the yards, masts, hull and wooden fittings. Last came petty officers, consisting of men with various specialized skills.

One seaman described in his memoirs how:

We had a midshipman on board of a wickedly mischievous disposition, whose sole delight was to insult the feelings of seamen and furnish pretexts to get them punished … He was a youth of not more than 12 or 13 years of age; I have often seen him get on to the carriage of a gun, call a man to him, and kick him about the thighs and body, and with his feet would beat him about the head; and these, though prime seamen, at the same time dared not murmur.

Prior to battle, a midshipman would see that all the guns, powder cartridges and associated equipment were ready for use. When a ship stood in harbour, a specified number of midshipmen would be assigned to work around the clock in shifts, supervising the upper deck. As a midshipman was an aspiring officer, he spent what time remained between watches studying mathematics, navigation, trigonometry and seamanship, as well as writing in his journals. After about six years’ service, by which time he would be about 19, a midshipman would take his examination for lieutenant.

While lieutenants with sufficient experience commanded one of various types of small vessels such as sloops, armed cutters, brigs or schooners, they are best known as the group of officers immediately junior in rank to the captain. A lieutenant was expected to carry out the orders of the captain or more senior lieutenants quickly and intelligently, whether serving as the officer of the watch or in some other capacity. Specifically, he was to ensure that the ship sailed according to the course and direction dictated by the captain, and remain attentive lest rigging and sails suffer damage from a sudden shift in the direction and strength of the wind. According to Admiralty Regulations, the lieutenant of the watch was to remain on deck in a constant state of vigilance:

To see that the men are alert and attentive to their duty; that every precaution is taken to prevent accidents from squalls, or sudden gusts of winds; and that the ship is as perfectly prepared for battle as circumstances will admit.

A lieutenant was also responsible for the conduct of the midshipmen, mates and seamen under him, ensuring that they all carried out their duties properly. The senior lieutenant on duty was immediately to call the captain on deck if the weather suddenly changed, or if some other pressing matter required his attention.

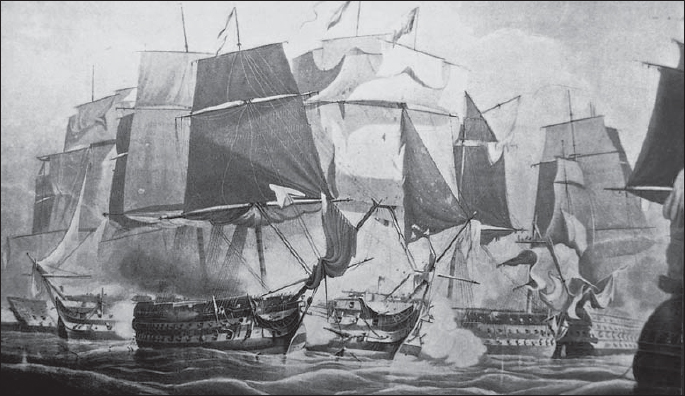

Trafalgar. By breaking the Franco-Spanish line in two places, Nelson was able to isolate Admiral Villeneuve’s centre and rear, thus compensating for the allies’ numerical superiority. (Philip Haythornthwaite)

Apart from the smallest ships, aboard which only one or two lieutenants served, each ship had a first lieutenant, whose seniority, based on experience, entitled him to the post of second in command. As such he was to report directly to the captain respecting the management of the ship and its crew. He ensured that watch and quarter bills were implemented correctly, which required him to list where all officers, seamen and marines were to be positioned when on watch or in action. The list also laid down the responsibilities to be undertaken by each man so as to cover all eventualities, such as manning the pumps, fighting fires, serving in or leading a boarding party, and sail-handling. The first lieutenant normally did not keep watches, but might be called on deck as needed by the officer of the watch. During battle the first lieutenant stood with the captain on the quarterdeck, and in the event of the captain being injured or killed, command immediately devolved upon the first lieutenant.

The more junior lieutenants each commanded a gun deck in action and oversaw the firing of the guns. With the assistance of midshipmen and quarter gunners, the lieutenant was responsible for seeing that the gun crews always had powder and shot to hand and that the men handling and firing the guns did not abandon their posts under the pressure of enemy fire. Any of the lieutenants not assigned to a particular gun deck would command the guns on the forecastle or quarter deck, or were positioned on the poop deck and given charge of signalling in the capacity of communications officer.

This rank was assigned to officers who commanded vessels smaller than a sixth rate, which is to say sloops and brigs. By the second year of the war, in 1794, the rank was replaced by that of commander, which was effectively the same as a captain of a larger vessel, the only distinction being that a commander was responsible for fewer men and guns.

A captain (or ‘post captain’, which distinguished the position from that of ‘commander’ who was effectively a ‘captain’ already, but merely of a small vessel) always commanded a ship of sixth rate class and above. These men normally rose from the rank of commander, though those who demonstrated particular promise or who had distinguished themselves might only hold the rank of commander very briefly before becoming captain. The captain was junior only to his superior squadron commander, who held the rank of commodore or admiral. Thus, aboard his own ship, the captain reigned supreme. He was ultimately responsible for all aspects of the running of the ship, not least the discipline of the officers and men, and directed the ship’s course and conduct during battle.

The rank of commodore was rarely filled, for it was in fact an intermediary post occupied by a senior captain temporarily commanding a small squadron or an important position on shore in the absence of an admiral. Specifically, the rank of commodore existed to satisfy the requirement of assigning part of a fleet to a senior captain while the admiral was commanding the remainder of the fleet on another assignment, or where the admiral was absent from the fleet altogether. A commodore could command an inshore squadron or a small number of ships, usually frigates, detached from their parent fleet to conduct the blockade of an enemy port, or he might also be assigned a particular task of attacking an enemy squadron or bombarding a position on the coast. If, as was usually the case, the appointment of commodore was only temporary, upon the expiration of his tenure the captain would revert to his own rank.

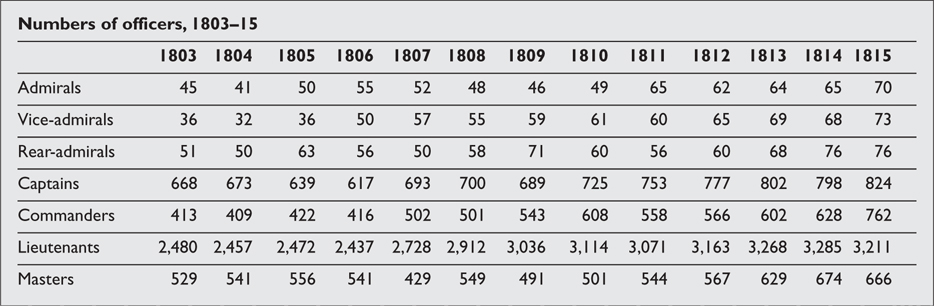

Those in command at the highest level, in the name of the Admiralty, were the admirals, who led squadrons of approximately ten or more ships, or two or three squadrons, which composed a fleet. These men, all with years of practical experience dating back to the time they joined the Navy as midshipmen, were promoted automatically by seniority from the rank of captain. By the time they reached this rank they had demonstrated thoroughly their abilities at seamanship and command. They were expected to have a good grasp of strategy and be relied upon to execute the Admiralty’s orders with steadfastness and intelligence, since poor communication and great distances would often require an admiral to use considerable discretion in the interpretation of his orders. The members of the Admiralty generally knew admirals personally, and therefore were confident in entrusting them with direct responsibility over large numbers of ships and men. Not all admirals were suited to fleet command. Some performed administrative tasks ashore, some commanded shore establishments, and others governed British colonies. Admirals could retain their positions and rank for life, and thus they could be quite old and inefficient. Some took voluntary retirement on a sizeable pension; others worked until infirmity or death. There was no shortage of men from which to choose admirals, and by 1807 there were over 150 of them, often known as flag officers.

The battle of Trafalgar, a victory so comprehensive as to confirm British naval supremacy for the next hundred years. (Philip Haythornthwaite)

Unsurprisingly, an admiral in charge of a fleet (normally comprising at least 20 ships of the line, plus ancillary vessels, especially frigates) had myriad responsibilities, as shown by Keith’s orders of 1799, which included 15 clauses. He was instructed:

To correspond with the governors of Gibraltar and Minorca, and all British consuls in the Mediterranean;

To give every assistance to the governor of Gibraltar;

To appoint such of His Majesty’s ships and vessels under your command to convoy the homeward bound trade, as are the least fit to remain abroad, as you shall judge sufficient for their protection;

To detain and keep under his command any ships sent out to him, except storeships, which were to be sent back when unloaded;

To send surgeon’s mates to help in Gibraltar hospital if needed;

To have his ships apply for provisions at Gibraltar;

To notify the Admiralty of any store and provisions lacking;

If purchasing any ships and vessels, to get Admiralty permission, and to have them surveyed by the commissioners at Gibraltar;

To conform to the established rules and customs of the navy;

Not to appoint any victualling officers on shore, but to apply to the Admiralty for permission;

To visit ships and muster men, and see that they were rated properly, and to look to the cleanliness and economy of ships under his command;

To have his ships refitted at Gibraltar and Minorca;

To order his captains to take good care of rigging, stores and so on;

Not to allow his ships to come home except in cases of necessity;

And to keep a journal, and send regular reports to the Admiralty.

The battle of San Domingo, 6 February 1806. Fought off the east end of the island of Hispaniola, in the West Indies, where a squadron under Vice-Admiral Sir John Duckworth defeated his French counterpart, Admiral Leissègues, whose vessel was forced ashore. As the British commander later reported to the Admiralty: ‘the French admiral, much shattered and completely beaten, hauled direct for the land, and, not being a mile off, at 20 minutes before noon ran on shore, his foremast then only standing, which fell directly on her striking.’ (Stratford Archive)

Admirals were classified according to three divisions, each of which contained three ranks. In the wake of the Anglo-Dutch wars of the 17th century, the Navy was divided into three squadrons, with a single colour designated for each, based on seniority: red was the highest, followed by white and blue. This flag was flown at the ensign staff of each ship in the fleet, though it is important to note that the white ensign was later altered to include the red Cross of St George in order to distinguish it from the flag of Bourbon France, whose flag was also white (though all possibility of confusion ceased when from about 1795 the French began to fly the revolutionary Tricolour). Admirals, like the red, white and blue squadrons of the fleet, were themselves subdivided into individual ranks, the most senior rank being (full) admiral, followed by vice-admiral and rear-admiral.

An admiral senior enough to command an entire fleet rather than merely a squadron normally positioned his flagship at its centre, whereas a vice-admiral, serving as second in command, directed the activity of the van (the leading squadron of the fleet), with a rear-admiral, as his title implied, commanding the rear. The senior post in this hierarchy – Admiral of the Red – required an officer to rise nine places once he was promoted from captain or commodore. Thus, his long ascent, facilitated by the retirement and death of those senior to him, began as Rear-Admiral of the Blue, which was the lowest rank of the lowest squadron. This was modified in 1805 when the rank of Admiral of the Red was redesignated to fall between Admiral of the Fleet and Admiral of the White, thus requiring those seeking the highest position to ascend ten places on the ladder of promotion. The most senior position of all – Admiral of the Fleet – entitled the holder of that rank to fly the Union flag (or ‘Jack’) at the head of the main mast.

Richard, Earl Howe (1726–1799). Commander of the fleet on the North American station during the War of American Independence (1775–83), Howe was one of Britain’s most accomplished naval commanders, finishing his career with his tactical victory over the French at the battle of the Glorious First of June in 1794. He provided assistance to his brother, Sir William Howe, commander of British forces in North America, between 1776 and 1778, before assuming command of the Channel Fleet, in which capacity he brought relief to the besieged British garrison at Gibraltar. At the Glorious First of June, Howe captured six French ships from the fleet under Admiral Villaret-Joyeuse, for which achievement he was promoted to full admiral. He retired in 1797, though he was held in such high esteem that the Spithead mutineers approached him with their petition for referral to the government. (Philip Haythornthwaite)

The ranking of admirals can thus be summarized as follows:

Admiral of the Fleet

Admiral of the Red (rank created after 1805)

Admiral of the White

Admiral of the Blue

Vice-Admiral of the Red

Vice-Admiral of the White

Vice-Admiral of the Blue

Rear-Admiral of the Red

Rear-Admiral of the White

Rear-Admiral of the Blue

Seamen were categorized as befitted their experience and ability, and were divided into three rates: ordinary seaman, able seaman and petty officers. These men generally worked aloft, maintaining the sails and all the lines that controlled them, splicing and knotting, handling the rigging and heaving the anchors. Each man would perform his duties on one of two or three ship’s watches, and bore responsibilities connected with each mast. As described earlier, topmen – the fittest and, often, the youngest and most agile men – worked in the highest yards where work was precarious but vital. Older, stronger seamen performed their duties amongst the lower yards and on the forecastle. Finally, those of the afterguard worked on the quarterdeck and around the mizzen mast. Once battle commenced, however, most of the men, whatever their usual station, would be required to work the guns. Thus, in the course of only a short period at sea the ratings acquired a host of skills that enabled them to work in various capacities aboard ship. Beneath the ratings were landsmen who possessed no skills in seamanship and therefore were used for their brute strength to haul on ropes, rotate captans, and perform other laborious tasks. They could potentially acquire skills in the rigging if the captain allowed them into the lower rigging, but for the most part they remained on deck.

An ordinary sailor could rise to able seaman, which depended on his ability in certain skills. According to the Admiralty:

The letters A.B., which mean Able Seaman, are placed against the names of only those who are thorough-bred sailors, or who, in the sea phrase, can not only ‘hand reef and steer’, but are likewise capable of heaving the lead in the darkest night, as well as in the daytime; who can use the palm and needle of a sailmaker; and who are versed in every part of a ship’s rigging, in the stowage of the hold, and in the exercise of the great guns … In these, and twenty other things which might be pointed out, he ought to be examined by the Boatswain and other officers before his rating of A.B. is fully established on the books.

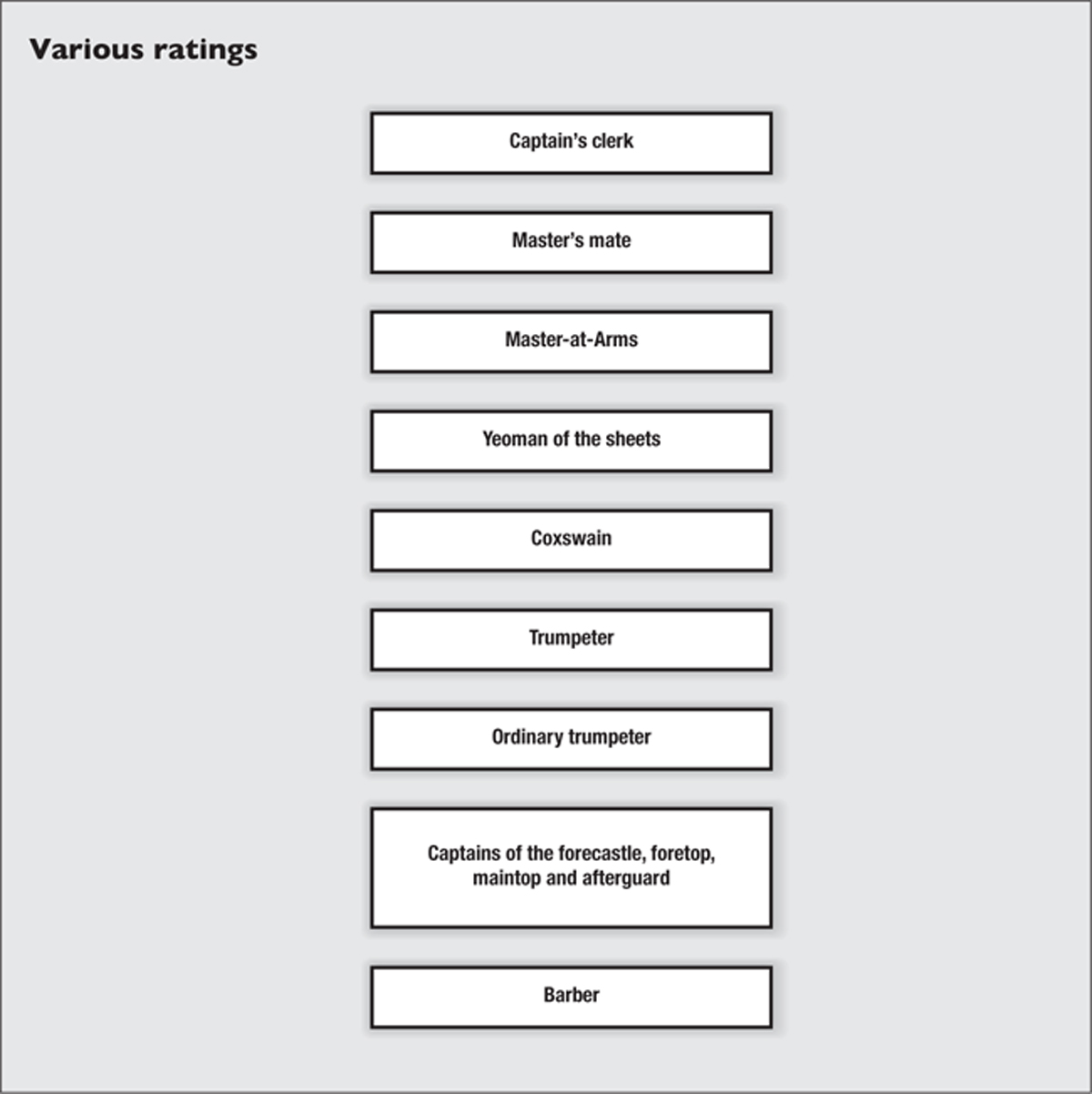

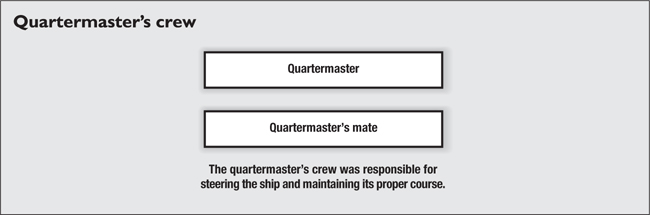

Examples of some of the many titles held by ordinary seamen aboard a British warship. In addition to his specialist skills, nearly every sailor understood the functions of the many miles of the ship’s rigging and could find the correct line even in darkness or in the midst of a storm. He could tie perhaps two-dozen knots with ease, splice ropes in several ways and recognize the many hundreds of features aboard his vessel, from sails and spars to armament and equipment. If sent aloft, he could speedily make his way to the end of a yardarm to furl or reef a sail as required, applying his strength and dexterity under highly dangerous conditions.

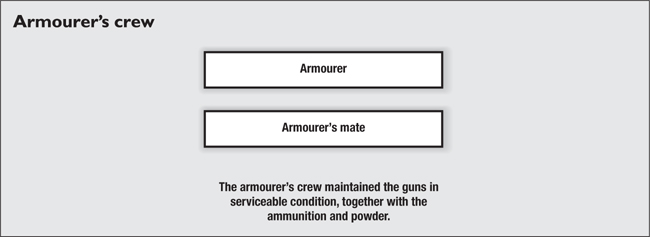

Warrant officers were men with specialist skills responsible for the maintenance and management of the ship. In contrast to officers of the wardroom who had become lieutenants with a commission granted by the Admiralty, the warrant officer received his commission independently from the Navy Board. Warrant officers had to be literate, as they were required to manage the ship’s stores and keep an accurate account of them. They were subdivided into four categories, the first of which contained men enjoying the privileges of the wardroom and consisted of the master, surgeon, purser, chaplain and schoolmaster. The second category comprised the standing officers, being the boatswain, gunner and carpenter. The third section consisted of petty officers – the master-at-arms, sailmaker, armourer and carpenter’s mate. Finally, belonging more properly to the lower deck, were the cook, caulker, ropemaker and sailmaker’s mate.

The master was the most senior warrant officer, and was responsible to the captain for everything concerning navigation, steering and the general manner of sailing the ship. Thus, the master had charge of all navigational instruments, including charts, compasses, nautical tables and astronomical instruments. His additional duties required him to look after the condition of the rigging, sails, anchors and cables. It was his responsibility moreover to ensure that the ship sat evenly in the water, which meant that he had to supervise the stowage of provisions. Stores improperly loaded would adversely affect the ability of the ship to sail at its most efficient and could even imperil those aboard by causing the ship to heel. The master also maintained the security of the ship and had charge of the spirits aboard it, as well as the ship’s logbook, or journal. It was this vital document that was produced at a court martial in the event the ship grounded, foundered or was otherwise lost. Masters often entered the Navy from the merchant marine, though others joined first as midshipmen or lieutenants, or had attained their rank by advancing up from quartermaster or as a mate from the lower deck.

The Surgeon was not trained by the Navy, but would have learned his profession as a civilian and then entered naval service after passing an exam at Surgeon’s Hall in London or by a Physician of the Fleet if he applied for work while abroad. The Navy Board having granted him a warrant, he then served an apprenticeship as a surgeon’s mate before receiving promotion to surgeon.

HMS Sibylle (38) in single combat with La Chiffonne (36) off Mahé, on the Indian coast. On 18 April 1801, discovering the French frigate anchored with a damaged foremast, Captain Charles Adam anchored 200yds from his opponent and began an action lasting 17 minutes, in the course of which the Sibylle received raking fire from a French battery positioned on the coast (left background). La Chiffonne, having suffered 53 killed and wounded, cut her cable, lowered her flag in token of surrender, and drifted on to a reef. Captain Adam, with only two men killed and one wounded, sent a boat to take possession of the prize and, turning his guns against the enemy battery, forced its surrender. As with most French vessels captured in serviceable condition, the Admiralty purchased La Chiffonne and commissioned her into the Royal Navy. (Stratford Archive)

Over 700 surgeons served in the Navy during the French Revolutionary and Napoleonic Wars. As to be expected, the surgeon was responsible for the health of the officers and crew, from administering the very crude forms of medicine of the time to those laid up ill, to coping with injuries from accidents, to performing operations, particularly in the wake of battle. He was also responsible for the management of the ship’s sick berth, which stood on the orlop deck.

It was generally maintained that:

A naval surgeon of abilities and circumspection is generally the most independent officer in the ship, as his line of duty is unconnected with the others. He has the entire charge and management of the sick and hurt seamen on board his ship; is to perform surgical operations on the wounded as he may deem necessary to the safety of their lives; and to see that the medicines and necessaries with which he is supplied from the said board, or their agents, are in good in kind, and administered faithfully to the sick patients under his care.

Much has been said about surgeons being quacks or drunkards; clearly a few were incompetent or inebriated on duty, but most surgeons were well-intentioned and conscientious men with a good understanding of contemporary medical science (such as it was), who did their best under difficult circumstances.

Indeed, the difficulty of those circumstances is difficult to exaggerate. Surgeons had to cope with every conceivable malady and injury on a daily basis, including seasickness, abscesses, boils and toothache, to physical injuries – a common problem aboard ship with strenuous work so much a part of the regular routine – such as fractures caused by falls or concussion resulting from banging one’s head on low deck beams or being struck by a falling object. The daily lifting and lowering of heavy objects like casks, barrels and boxes sometimes resulted in internal injuries and hernias.

Surgeons faced all manner of illnesses to try to prevent and treat, a problem exacerbated by the fact that contagious disease spread easily in an environment where all hands were confined to a small space. Thus, influenza, typhus and consumption (tuberculosis) could strike many members of the crew in a short period, while tropical diseases – malaria, cholera and yellow fever being the most common – found their way aboard, particularly among vessels operating in West Indian waters. Yellow fever was amongst the nastiest and most difficult diseases to treat.

On the rare occasions when men were allowed ashore, they sometimes returned with gonorrhoea and syphilis, and though scurvy had largely been eradicated by this time, it could occasionally crop up when supplies of fresh fruit and vegetables were exhausted and no rapid means of replenishing them existed. The resulting bleeding gums, listlessness and anaemia caused by the lack of vitamins became a daunting challenge to a surgeon for whom the necessary medications and citrus juices were unavailable.

Infection was one of the most common causes of death, whether from simple cuts or bullet or splinter wounds, the latter of which required either probing for the foreign object or amputation. If a limb were removed, the surgeon had to tie off the severed arteries and blood vessels with ligatures that were then left and allowed to fall off from the stump over time, thus leaving the exposed area at risk from infection. A sailor could endure a considerable amount of pain during the course of an operation – particularly in an age of regular hardship – but he still faced the great risk posed by post-operative infection, which, at its most extreme, could develop into gangrene or tetanus. Gangrenous tissue could be cut away during a subsequent operation, but lockjaw usually resulted from tetanus, from which recovery was rare.

During battle the most common injury was caused by flying splinters, showers of which were produced by shot striking and shattering wood planking, beams, stays and other features of the ship. A man hit by a ball itself might survive, though usually not without the loss of one extremity of another. In the midst of battle surgeons attended patients in the order in which they fell, irrespective of rank or severity of injury; triage did not yet exist. Amputation was commonplace and was carried out in a matter of minutes, not simply because of the urgency of other cases, but owing to the absence of anything like modern anaesthesia. A blow to the head or abdomen from a round shot usually spelled instant death, and there were many recorded instances of men being decapitated, though injuries of various kinds always outnumbered deaths. Surgeons also had to tend to men who received burns from the discharge of the guns or from fire; fever and shock often followed such traumas to the body. Perhaps the most unlikely form of death connected with combat was what contemporaries called ‘wind of ball’, which meant the internal injuries caused by the flight of a round shot in close proximity to the victim’s body. No outward signs of wounds were produced by this phenomenon, but there are a number of documented instances of passing shot, speeding past a seamen, causing instant death, though the victim was sometimes spared when the projectile passed his head rather than his abdomen.

| Estimated number of fatal casualties in the Royal Navy, 1793–1815 | ||

| Cause of death | Number | Percentage |

| Individual, non-combat (illness and personal accident) | 84,440 | 81.5 |

| Collective, non-combat (foundering, shipwreck, fire, etc.) | 12,680 | 12.2 |

| Enemy action | 6,540 | 6.3 |

| Total | 103,660 | 100 |

The death of Lieutenant Grant at Copenhagen – a heavily sanitized version of the actual event, in which a round shot carried away Grant’s head. The deck would also have been strewn with torn canvas, spent ammunition, severed lines, splinted wood, fallen men and pools or rivulets of blood, depending on the roll of the ship. (Philip Haythornthwaite)

The purser served in a civilian capacity in charge of managing the provisions aboard ship. As such, he procured all the food, spirits, wine, clothing, tobacco, bedding and other provisions needed for the entire ship’s company. He actually ran a business of sorts, for while the Navy provided these various commodities, the purser was required to purchase some of these items with his own means and sell them on to the crew either for a profit in the case of clothing, or slightly under weight, in the case of food, profiting from the difference. Thus, for every pound of food supplied to the ship, the purser issued 14 ounces. When he sold clothing or tobacco he took a commission of five per cent and ten per cent, respectively. He also managed the distribution of coal and wood for the galley fire, the heating stoves of the officers’ cabins and the lower decks, as well as lanterns, candles, wooden cutlery and other items.

The chaplain held the same rank as the master and surgeon, though obviously his position was not so essential to the daily routine of the ship. As a result, very few could be found aboard ships lower than third rates. Chaplains during this period were in all cases Anglicans, with responsibility for conducting religious services every Sunday for the entire ship’s company, irrespective of the denominations actually represented. They were always in attendance at funeral services, which in almost all cases concluded with burial at sea, and held services of thanksgiving after battle. Chaplains were often learned men with training in theology, classical languages and modern languages – these last skills being useful in interpreting captured or intercepted dispatches and in communication with foreign ships and ports.

The schoolmaster, normally only found on a ship of the line, was principally concerned with the education of midshipmen in mathematics, theoretical navigation and trigonometry in order to prepare them for commissioning. Candidates for schoolmaster underwent an examination to ensure their fitness for the post. They might also teach reading and writing to the younger members of the crew.

The boatswain held many responsibilities and was answerable to the ship’s master for all matters connected with the rigging, sails, cordage, blocks, anchors, cables and ship’s boats. The boatswain was greatly experienced in all aspects of seamanship, and held the rank of a standing officer, which meant that he remained aboard the ship even when it was laid up and out of service. This ensured that when the ship was recommissioned, the same boatswain bridged the transition, for his intimate knowledge of the ship was invaluable to the captain. The boatswain not only inspected the rigging every day, but saw that his mates (all petty officers) roused the men to take up their watch on deck or aloft. Regulations required that he be:

Admiral Cuthbert Collingwood (1750–1810). Collingwood commanded the Barfleur (98) at the battle of the Glorious First of June in 1794, but later transferred to various other ships, eventually becoming captain of the Excellent (74), then serving in the Mediterranean. In 1797 he distinguished himself at the battle of St Vincent where he captured two Spanish ships. Thereafter Collingwood took part in the blockade of Cadiz, becoming a rearadmiral in 1799 and transferring to the Channel Fleet, which blockaded Brest. Promoted to vice-admiral in April 1804, he commanded a squadron that joined Nelson off the Spanish coast in the autumn of 1805. At the battle of Trafalgar Collingwood, second in command, led the lee column and succeeded to commander-in-chief of the Mediterranean Fleet on Nelson’s death. Collingwood continued to serve in the Mediterranean until he succumbed to exhaustion and died in 1810. (Philip Haythornthwaite)

Very frequently upon deck in the day, and at all times both day and night, when any duty shall require all hands being employed. He is, with his mates, to see that the men go quickly on deck when called, and that, when there, they perform their duty with alacrity and without noise and confusion.

Responsible for the sails and a large amount of stores and equipment, the boatswain was required to provide monthly accounts to the captain indicating the articles purchased or used during that period. To prevent fraud, the ship’s provisions were gathered and inspected by boatswains from other ships, and the boatswain would in turn perform the same service aboard other vessels. Prominent among his responsibilities was ensuring that the sails were kept in good condition and properly aired and dried. The boatswain saw to it that all the stores were removed and stowed ashore during re-fitting or when the ship was laid on its side and cleaned, a process known as ‘careening’. Once the ship was ready for sea, the boatswain ensured that all the stores were returned aboard. While the ship sat at anchor, the boatswain saw that the sides were washed and kept free of lines or ropes.

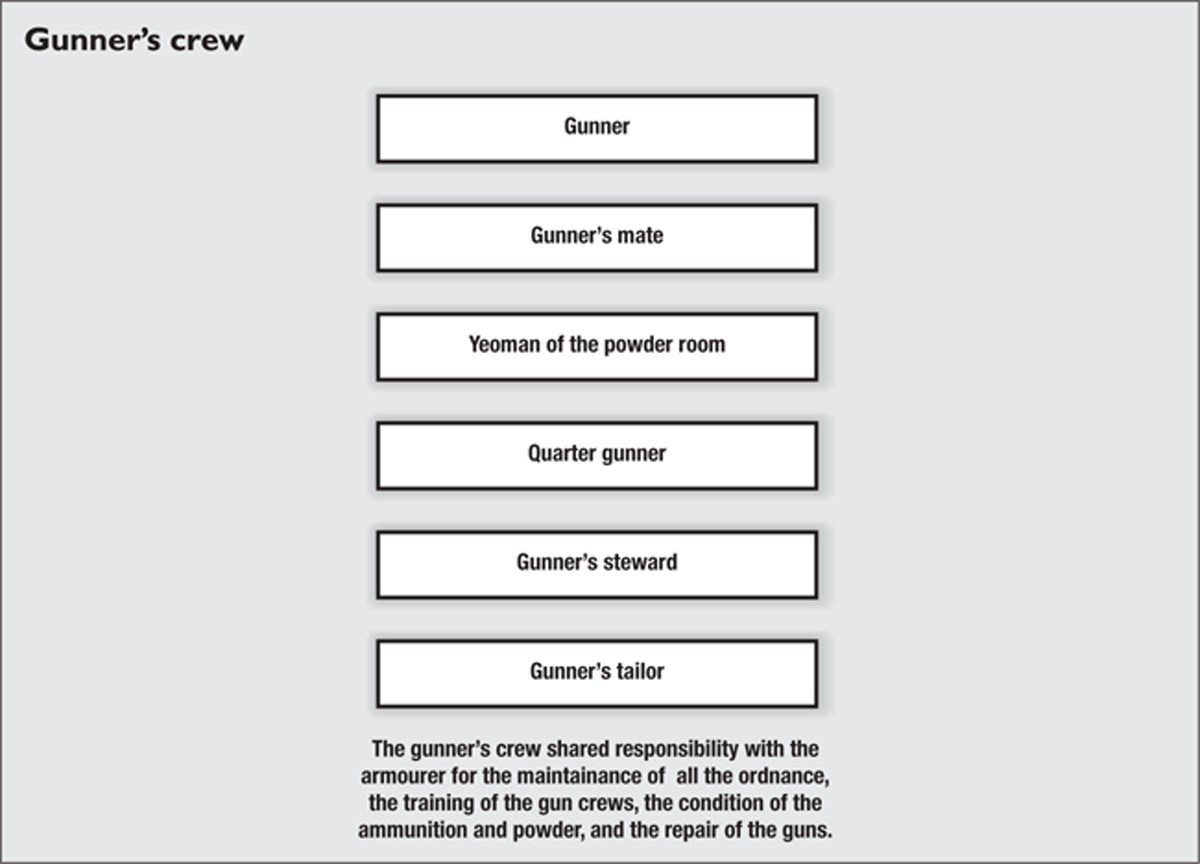

The gunner was responsible for the ship’s ordnance, which meant more than merely the guns themselves, but also the magazines, gunpowder, shot, cartridges, gunlocks and other equipment such as small arms and edged weapons. The gunner remained with the ship when it was decommissioned, ensuring that it was ready for service at short notice. Together with the Inspector of Ordnance, who was dispatched by the Board of Ordnance, the gunner inspected all the guns and carriages supplied to the ship. He also checked to see that all magazines were dry and ready for the arrival of the powder to be stored there. In addition to examining all the stores and equipment connected with gunnery, the gunner had charge over his mates, the quarter gunners, yeoman of the powder room and gun captains, and saw to the training of the gun crews.

British sailors and marines made numerous landings on enemy coastlines, either in support of the Army or to attain objects of naval significance. Landing parties carried out raids on docks, anchored naval vessels, fishing or merchant fleets, gun emplacements and arsenals in ports, and on fortified positions. Aboard ship, marines stood guard over the captain’s cabin, the magazine and the ship’s supply of alcohol, enforced discipline amongst the crew, lent their muscle for particularly arduous tasks such as raising the anchor, and sniped at the enemy during battle. (Philip Haythornthwaite)

As with the boatswain, the gunner was responsible for a large amount of stores and equipment, and thus had to provide accounts to the captain on a monthly basis showing the articles expended. In addition, he would account for the amount of powder, shot and small arms ammunition expended during practice firing. Again, like the boatswain, the gunner’s stores were inspected by gunners from other ships to protect against fraud, and in turn he himself would be called upon to do the same aboard other ships. When the ship sat in dock for refitting or to be heeled over and its hull cleaned to remove barnacles and other sea creatures, the gunner saw that all the guns and associated stores were transferred to facilities in the dockyard. When the ship was ready again for sea, the equipment and guns were then re-embarked.

The carpenter had to serve a seven-year apprenticeship on shore before taking up his position aboard ship, which meant that he would have begun his trade as a civilian. He might then have spent another seven years in the capacity of a carpenter or shipwright before joining the Navy. Many such men had worked in the Royal dockyards or in private facilities or been seized from merchant ships. The carpenter was responsible for a large quantity of supplies and equipment and therefore was accountable to the captain every month with lists showing the items expended in the course of his duty. He used specialist equipment, plus an array of other items such as nails, bolts, copper and lead sheeting, glue, glass, paint, pitch and tar. The nature of his trade also required that he managed a supply of timber to enable him to repair the hull, as well as spare spars which lay in a crudely cut state to be prepared to the required specifications, whether for yards or topmasts, as circumstances demanded. The carpenter paid particular attention to masts that split as a result of heavy seas or high winds. In these cases, he attached a type of splint to reinforce them. As with the boatswain and gunner, the carpenter’s stores were periodically checked to ensure that he was not engaged in fraudulent activity. As the carpenter worked only during the day, he did not keep watches like most of the rest of the ship’s company, and hence came under the category of ‘idler’.

Carronades in action. Gun crews varied in number depending on the size of the weapon: the heavier the ordnance the more men were required to handle it. These numbers fluctuated in any event, since some members of the crew might fall in battle or could be called away to perform another duty, such as taking part in a boarding party, working a pump when the ship sprang a leak or suffered an injury below the waterline, trimming the sails, or plugging a hole. Normally, the guns on one side of the ship remained unengaged, which meant that half the gun crews were theoretically available to assist their counterparts on the opposite side of the deck. In this case, the gun captain on the engaged side remained in command of his weapon, while his counterpart from across the deck became his second in command. (Angus Konstam)

The carpenter was responsible, in addition to the aforementioned tasks, for determining if the hold contained any water that had leaked in, and if so to see that it was pumped overboard. He ensured that all the ship’s pumps were in proper working order – a vital service, for without them the ship potentially stood in mortal danger. Water trapped in the bilge also had to be extracted, for it could have a deleterious effect on the health of the crew. The carpenter and the carpenter’s crew played an important role in action, when they stood in the depths of the ship, below the waterline, ready to plug shot holes with oakum, nails, sheet lead and wooden plugs. When the ship was moored for refitting or careening, the carpenter would see that the hull was properly shored up by stout timbers, and that any newly fitted masts were firmly fixed at each deck level.

The armourer worked with the gunner, looking after the small arms, both firearms and edged weapons, including muskets, pistols, cutlasses, pikes and tomahawks (sometimes called ‘boarding axes’). In this respect he possessed skills as a blacksmith and understood and could repair the mechanisms and component parts of firearms. His task extended beyond weaponry to a limited extent, for he repaired anything aboard ship made of iron and could produce replacement articles such as nails, bolts and hinges. Often a civilian locksmith or blacksmith before entering naval service, the armourer repaired locks and any other device that required skills in metalwork.

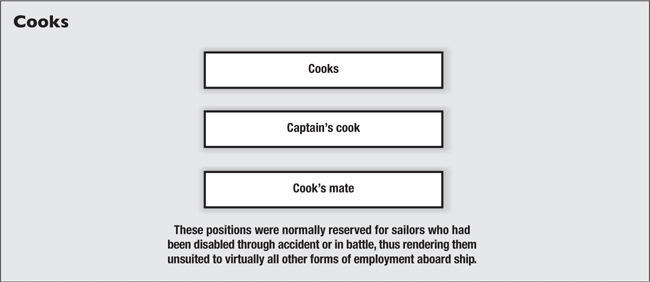

A ship’s cook need not have any specialized skill in cooking, though he occasionally had civilian experience of working in a tavern. Occasionally the cook was a disabled sailor whose impairment fitted him for no other position aboard ship. The most junior of the warrant officers, the cook nevertheless held this position above the ordinary seamen as he had the important responsibility of maintaining the safety of the galley stove fire – the only major fire hazard aboard ship. In addition to preparing the ship’s company’s meals, the cook had to present clean utensils and pots for inspection every afternoon.

| Ship losses through accident, 1793–1815 | ||||

| Rating | Foundered | Shipwrecked | Burnt/exploded | Totals |

| Line (64 guns and over) | 3 | 17 | 8 | 28 |

| Frigates | 4 | 67 | 2 | 73 |

| Sloops, brigs, etc. | 68 | 170 | 5 | 243 |

In addition to its ordinary crew, every warship from sloops through frigates and ships of the line was supplied with a contingent of marines, who comprised about a fifth of a ship’s company. Approximately 120 marines served aboard a 74-gun ship, whose full complement numbered about 550. About 150 served aboard a first rate. Marines (who were designated ‘Royal Marines’ from April 1803) had originated as soldiers, drawn from foot regiments and assigned for service at sea. Unlike many sailors, marines were never pressed, but rather were composed entirely of volunteers who normally agreed to serve for the duration of the war. Many other differences separated sailors and marines, as one contemporary observer noted:

No two races of men, I had well nigh said two animals, differ from one another more completely than the ‘Jollies’ and ‘Johnnies’. The marines … enlisted for life, or for long periods as in the Regular Army, and, when not employed afloat, are kept in barracks, in such constant training, under the direction of their officers, that they are never released for one moment of their lives from the influence of strict discipline and habitual obedience. The sailors, on the contrary, when their ship is paid off, are turned adrift, and so completely scattered abroad, that they generally lose … all they have learned of good order during the previous three or four years. Even when both parties are placed on board ship, and the general discipline maintained in its fullest operation, the influence of regular order and exact subordination is at least twice as great over the marines as it can ever be over the sailors.

The launch in 1766 of HMS Magnificent, one of many ships of the line constructed in the mid-18th century yet still serviceable during the Napoleonic Wars. (Stratford Archive)

When hostilities began in February 1793 the marines numbered only 5,000, but by 1802 they had expanded enormously to 30,000, a figure which remained about the same until fighting with France ended 12 years later. The Royal Marines were based at four locations: Chatham, Portsmouth, Plymouth and Woolwich.

Flogging. Discipline aboard ship was harsh, with sometimes dozens of lashes with a cat-o’-nine-tails administered for drunkenness, sleeping on duty, brawling and other infractions. Note the marines posted on the poop deck to ensure that the punishment is carried outwithout interference from the ship’s company, the whole of which was required to observe proceedings. The accused is shown strapped to a grating awaiting his fate, while in the centre another sailor appears to be confessing to the crime in order to spare his (presumably innocent) comrade. Flanking the captain (left foreground) is the first lieutenant and two particularly young midshipmen. Two carronades, easily recognizable by their characteristic slide mountings and short barrels, may be seen on the ship’s port side. (Stratford Archive)

Landing troops on shore. This was no easy matter, especially during a rough tide, as confirmed by one of thousands of British soldiers who disembarked in Mondego Bay, near Lisbon, in 1808: ‘A rapid succession of these boats, closely packed with human beings, went tumbling through the surf, discharging on the beach their living cargoes, with little damage beyond a complete drenching. But as the day advanced, the surf increased, and each succeeding boat encountered increasing difficulties in reaching land, (Philip Haythornthwaite)

The Marines performed two functions: when at sea when their ship was not in the presence of an enemy they stood watch at various points in the ship such as at the admiral’s and other officers’ quarters, the magazine, the spirit room (where alcohol was stored) and other areas that required some form of security. In this capacity, marines served to prevent indiscipline and mutiny, and it is unsurprising that their own quarters, separate from those of the sailors, were strategically located near the wardroom, thus providing a buffer between the officers and seamen. When not acting as sentinels, marines assisted in various tasks, such as in adding their strength to those seamen engaged in heavy lifting and hoisting. Marines often assisted in hauling ropes, turning the capstan when raising the anchor to get under way, and carrying heavy loads. Marines were not required to work amongst the rigging, but might do so as volunteers keen to acquire the skills of an able seaman.

When their ship engaged the enemy, the marines’ principal function was to provide small-arms fire, usually from the quarterdeck, when an opposing ship came within range of their muskets. They would also lead boarding parties or repel boarders on to their own vessel. Where their firepower and close-quarter fighting skills were not required, marines assisted at the guns, usually in some simple capacity that would enable them to leave this temporary post to assume their customary role elsewhere. During operations they provided a spearhead for soldiers or sailors, particularly against fortified positions and naval installations. Marines were also used in cutting-out operations, which involved seizing enemy vessels at anchor and either sailing them away as prizes or setting them alight. Marines could also be sent ashore to guard prisoners, weapons, powder or buildings.

British sailors and marines landing under fire at Aboukir Bay, on the coast of Egypt, 8 March 1801. (Philip Haythornthwaite)