Perhaps surprisingly, instructions to commanders-in-chief were not issued upon appointment, but rather, in lieu of a new set of orders, the new commander inherited the standing or unexecuted orders of his predecessor. Even then, he received little in the way of guidance, such that he regularly made decisions without regular communication with the Admiralty. This was natural, particularly for commanders in distant stations such as in the West Indies, the Indian Ocean and the Mediterranean. Instructions normally came in the form of individual dispatches. A station commander was expected to maintain a regular correspondence with the governors of British colonies in his area, overseas bases and army officers, consuls and diplomats ashore; to make decisions regarding convoy duty in his area of operations; ensure the proper supply of his fleet; detach squadrons or individual ships as needed to perform special tasks; to keep in regular contact with his squadron commanders and individual ship’s captains; to ensure the cleanliness and efficiency of the fleet; to arrange for ships to be refitted as necessary; to ensure that captains maintained the rigging, hull and stores of their ships in accordance with Admiralty regulations; and to send regular reports to the Admiralty on the affairs of his fleet.

Junior (vice- and rear-) admirals appointed senior captains to lead squadrons, particularly those composed of frigates. If, as it usually did, the fleet operated as a single cohesive force, junior admirals led divisions and squadrons within those divisions. A junior admiral led his division into action and saw that the individual ships in his division followed the orders of the commander-in-chief. The most senior of these men would also succeed the commander-in-chief in case of the latter’s death. A junior admiral might also command a detached squadron, such as Nelson did in 1798 when he was sent by his senior, Lord St Vincent, to pursue the French fleet which had left Toulon for an unknown destination – which in the event proved to be Egypt.

Beneath the admirals were the individual ships’ captains, who were responsible for the running of their ship. These men issued commands to their lieutenants who in turn executed them or passed them down to the midshipmen. The authority of the captain rested on more than his commission – and the fact that he could run his ship almost entirely as he saw fit – but on a combination of reward, punishment, courage, personal example and financial incentive. Thus, the captain possessed the power to promote on the spot anyone below the rank of midshipman and, indeed, often did in the wake of an action in which particular men had distinguished themselves. Punishments came in many forms, from ‘disrating’ (i.e. a demotion in rank) to the stopping of grog (the traditional sailor’s drink), to flogging, with a dozen lashes being the maximum allowed without recourse to a court martial. In practice, however, a captain need only charge the offender with several offences and tally up the lashes awarded. The most serious offences were referred to a court martial, which consisted of between five and 13 members, all officers. Large numbers of lashes could be ordered for those found guilty, or even hanging. Captains also depended on prize money to encourage their crews. A condemned prize could be sold to the Admiralty, with the proceeds allocated to the captors according to a man’s rank. Up to 1808 the captain was entitled to three-eighths of the prize money, with commissioned officers receiving one-eighth, warrant officers one-eighth, petty officers one-eighth, and the remainder of the crew, including marines, receiving one-fourth of the money paid for the prize. A new division of the spoils took effect from 1808

Earl Spencer, First Lord of the Admiralty, 1794–1801. The period of his tenure proved a remarkably successful one for the Royal Navy, which during these years seized nearly all of the French colonial possessions in the West Indies, decisively defeated the enemy’s Mediterranean Fleet, and generally drubbed it in all manner of engagements from ship-to-ship encounters to massive fleet actions. (Philip Haythornthwaite)

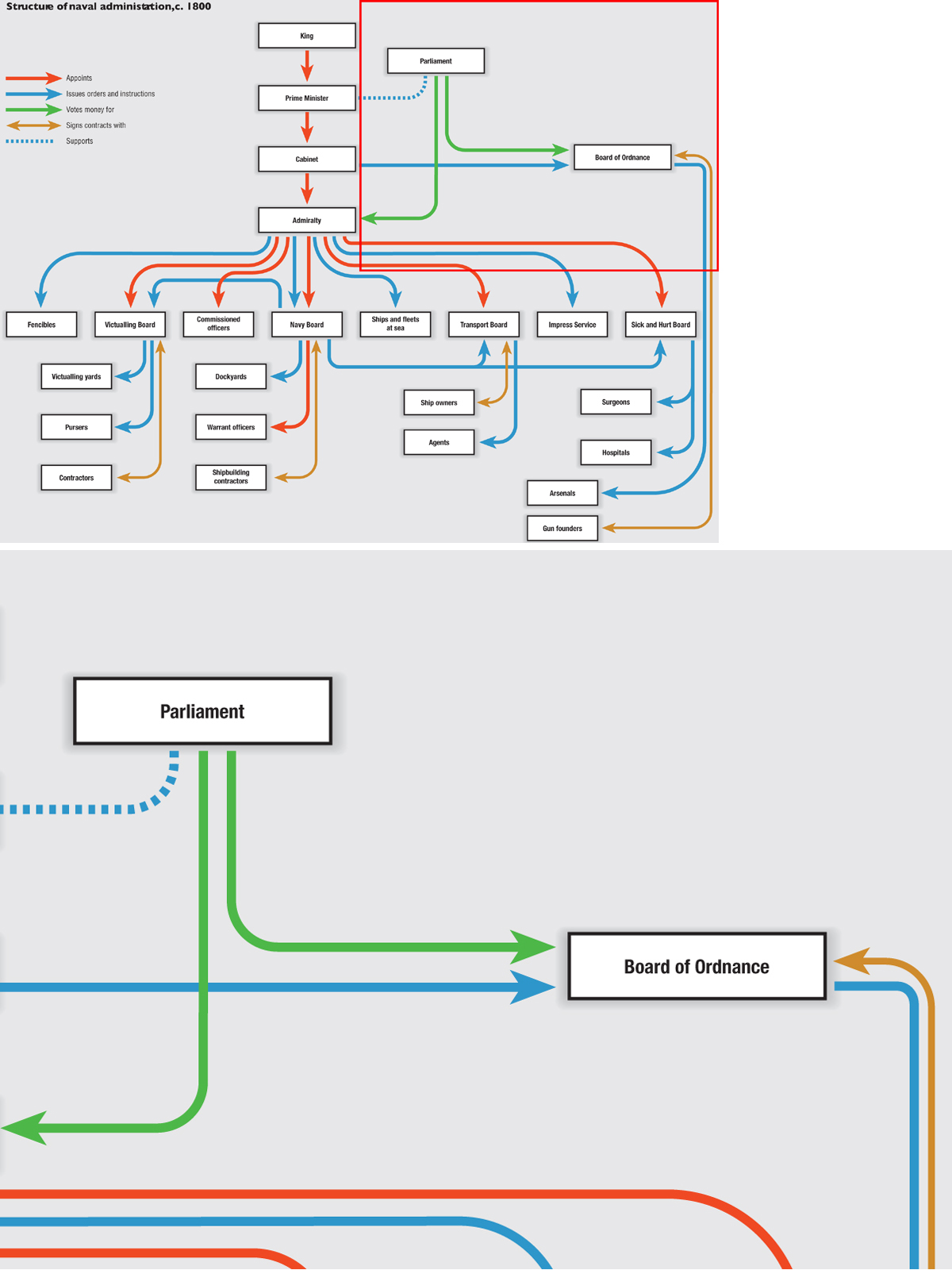

As Britain was a constitutional monarchy, the king, George III, did not exercise absolute power and relied on the prime minister and cabinet to make executive decisions, to which he almost invariably gave his consent, and to Parliament for the passage of laws and the allocation of funds for the running of the affairs of state.

With respect to the management of the Navy, the cabinet contained the First Lord of the Admiralty, whose decisions were subject to a consensus reached in cabinet meetings. Once a decision was made, the Navy depended on the House of Commons to vote it funds. The Commons, and to an extent, the House of Lords, took an active interest in naval affairs and regularly debated issues connected with the cost of the service and its role in the war. Above all, it voted the annual estimates that supplied it with money. The naval estimates were divided into three categories. The ‘ordinary’ funds covered the cost of maintaining ships and dockyard facilities. During peacetime these costs were generally higher, for during wartime much of the burden of maintenance was paid for under other categories. The second estimate was known as the ‘extra’, which were funds allocated for the construction of new ships. Lastly, Parliament conducted a vote to cover the cost of a particular number of seamen and marines, which largely determined the naval force available for that year.

The British Army was small as compared with Continental powers; the Royal Navy, on the other hand, exceeded 100,000 men and over 100 ships of the line, and had no comparable rival in the world, including France. Having said this, there were few checks to ensure that the money was used as intended, the number of men actually on service never quite reached the figures that Parliament pledged to fund, and there were no mechanisms to ensure that the money voted actually reached Navy coffers. More importantly, the money was never sufficient, so from year to year the Navy was chronically in debt. Contractors largely accepted this system, as payment eventually did reach them, so the Navy managed well enough from year to year, notwithstanding the fact that seamen’s pay could fall into arrears for years at a time.

| Naval expenditure, 1793–1802 | ||||

| Year | ‘Extra’ | ‘Ordinary’ | Number of seamen and marines | Total naval supplies granted |

| 1793 | £387,710 | £669,205 | 45,000 | £4,003,984 |

| 1794 | £547,310 | £558,021 | 85,000 | £5,525,331 |

| 1795 | £525,840 | £589,683 | 100,000 | £6,315,523 |

| 1796 | £708,400 | £624,152 | 110,000 | £7,613,552 |

| 1797 | £768,100 | £653,573 | 120,000 | £13,133,673 |

| 1798 | £639,530 | £689,858 | 120,000 | £13,449,388 |

| 1799 | £693,750 | £1,119,063 | 120,000 | £13,654,013 |

| 1800 | £772,140 | £1,169,439 | 120,000 | £13,619,079 |

| 1801 | £933,900 | £1,269,918 | 135,000 | £16,577,037 |

| 1802 | £773,500 | £1,365,524 | 130,000 | £11,833,570 |

Quite apart from the officers and sailors who manned the various fleets, the Navy required thousands of government officials, clerks, labourers, inspectors and others to support it. In terms of cost, technological sophistication and complexity, no other institution in the world could match it.

Responsibility for organizing the Royal Navy, planning and implementing its strategy and deploying its fleets and squadrons fell to, by modern standards, a remarkably small number of men at the Admiralty, who were responsible to the government. These seven men, the Lords Commissioners of the Admiralty, were not necessarily peers – indeed were often admirals – and answered to the First Lord of the Admiralty, who sat in the cabinet. As naval affairs were of such immense importance to the security of the nation, the Admiralty Board met on a daily basis in its offices in Whitehall, London, and determined the movement of ships as close as the Channel or as far away as the Indian Ocean and the Pacific. Supported by a working staff of 50 to 60, supervised by the First and Second Secretaries, the Admiralty performed various administrative functions, and saw to the commissioning and promotion of officers. These men exercised central control over the whole of the Navy, from determining the price the Navy would offer suppliers for food to deciding issues of great import such as the destination of a fleet in order to make contact with the enemy. Just as they exercised total control over the Navy, they also bore the burden of immense responsibility, for if through poor decision-making they contributed to major defeat, the security of the nation itself could be at stake.

At the time, the Royal Navy was the most complex and expensive institution not merely in Britain, but in the world, and its dockyards represented the largest industrial undertakings anywhere. From London the Admiralty executed the government’s instructions, major and minor, relaying orders by courier to the relevant ports, or using the telegraph system which, from 1796, connected London to Portsmouth, Chatham and Sheerness, and later to Deal. From 1806 a connection existed to Plymouth, and two years later to Yarmouth.

Employment at the Admiralty Office was much sought after, for it was well paid and clerks and officers often served for decades, with promotion available for those who acquired the requisite experience and demonstrated a high capacity for efficiency. Within the Office were four subsidiary boards: the Sick and Hurt Board, the Transport Board, and the Victualling Board, all of which were responsible to the Navy Board. The Admiralty was also responsible for the Royal Marines, the Fencibles (a type of seafaring militia) and the Impress Service (which, in all but name, kidnapped or otherwise compelled men into naval service), as well as for operating intelligence services.

| Expenditure on the Royal Navy, 1803–15 | ||||

| Year | ‘Extra’ | ‘Ordinary’ | Number of seamen and marines | Total naval supplies granted |

| 1803 | £901,140 | £1,488,238 | 100,000 | £10,211,378 |

| 1804 | £948,520 | £1,345,670 | 100,000 | £12,350,606 |

| 1805 | £1,553,690 | £1,394,940 | 120,000 | £15,035,630 |

| 1806 | £1,980,830 | £1,435,353 | 120,000 | £18,864,341 |

| 1807 | £2,134,903 | £1,557,934 | 130,000 | £17,400,337 |

| 1808 | £2,351,188 | £1,142,959 | 130,000 | £18,087,547 |

| 1809 | £2,296,030 | £1,408,437 | 130,000 | £19,578,467 |

| 1810 | £1,841,107 | £1,511,075 | 145,000 | £18,975,120 |

| 1811 | £2,046,200 | £1,578,113 | 145,000 | £19,822,000 |

| 1812 | £1,696,621 | £1,447,125 | 145,000 | £19,305,759 |

| 1813 | £2,822,031 | £1,700,135 | 140,000 | £20,096,709 |

| 1814 | £2,086,274 | £1,730,840 | 117,400 | £19,312,070 |

| 1815 | £2,116,710 | £2,278,929 | 90,000 | £19,032,700 |

| First Lords of the Admiralty, 1793–1815 | |

| 16 July 1788 | John Pitt, Earl of Chatham |

| 19 December 1794 | George Spencer, Earl Spencer |

| 19 February 1801 | John Jervis, Earl of St Vincent* |

| 15 May 1804 | Henry Dundas, Viscount Melville |

| 2 May 1805 | Charles Middleton, Lord Barham* |

| 10 February 1806 | Charles Grey, Viscount Howick (Earl Grey, 1807) |

| 29 September 1806 | Thomas Grenville |

| 6 April 1807 | Henry Phipps, Lord Mulgrave |

| 4 May 1810 | Charles Yorke |

| 25 March 1812 | Robert Dundas, Viscount Melville (until 1827) |

| * admirals | |

Each year the Admiralty commissioned ships with the funds provided for it by Parliament. The Admiralty was responsible for determining the basic specifications of a vessel before work began, with details provided respecting tonnage, dimensions, and the numbers and calibres of guns on each deck. Once these were laid down, the Surveyors of the Navy, employed in the Navy Board, would design the vessels on paper, to include details of the decks, hatchways, masts and other significant parts of the ship. Beyond this, the more intricate details such as the fitting and decorations were usually left to those at the dockyards themselves, where vessels were constructed either by workers at a government-maintained establishment, or by a civilian enterprise.

Admiralty Board Room. Decisions connected with the deployment of the Navy’s ships and their operations were made here by a handful of senior naval officers and civilians. Note the maps rolled up and mounted above the fireplace. (Royal Naval Museum)

The Admiralty, the branch of government responsible for most of the administration connected with the nation’s senior service and for the formulation and implementation of naval strategy. (Author’s collection)

The Navy Board, also responsible to the Admiralty, had to produce and deliver all the other needs of the Navy. This responsibility involved ensuring that ships were constructed, repaired and supplied with stores and equipment. The Board also controlled all the government’s shipyards. Much of its work was contracted out to civilian companies which themselves employed a civilian workforce, and thus the Navy Board was sometimes thought of as the civilian branch of the Navy. The Navy Board had to ensure that the ships were adequately manned, and it was to it that fell the unpleasant task of gathering crews for the always expanding fleets and paying the men their wages. The offices of the Navy Board stored thousands of documents including contracts, lists, reports and letters, all filed and maintained by hundreds of officials and clerks, supported outside London by inspectors.

John Jervis, 1st Earl of St Vincent (1735–1823). When war broke out with France in February 1793, Jervis commanded a naval expedition to the West Indies, where his squadron took the French islands of Martinique and Guadeloupe in the spring of 1794. He was briefly commander-in-chief of the Mediterranean Fleet in 1795–96, but the conclusion of a Franco-Spanish alliance obliged the British to withdraw their ships to the safety of Gibraltar. In February 1797, Jervis stood off Cape St Vincent, on the coast of Spain to prevent French and Spanish ships from the Mediterranean linking up with those at Brest with the intention of supporting a French invasion of Britain. Jervis’s victory over the Spanish on 14 February, aided by Nelson’s extraordinary conduct, put an end to the threat of invasion and Jervis was raised to the peerage as the Earl of St Vincent. In 1800 he took command of the Channel Fleet, and kept a continuous watch over Brest. He was appointed First Lord of the Admiralty during Henry Addington’s ministry between 1801 and 1804. Although dictatorial and harsh, St Vincent set high standards for discipline and contributed much to the organization of the Navy. (Philip Haythornthwaite)

The Navy Board was responsible for building and supplying the ships and managing the dockyards, as well as the purchase and manufacture of all the equipment and stores required by the Navy. It also appointed most of the warrant officers, many of whom it examined. This whole enterprise involved thousands of men. The Board was virtually independent of the Admiralty and was the only one of the four boards that kept accounts. The Navy Board consisted of ten members, a combination of naval officers and civilians, whom the Admiralty Board usually appointed for life. A commissioner from each royal dockyard had a seat on the Board, the whole institution led by the Controller of the Navy, who was invariably a senior officer. While the Admiralty commissioned ships, the Navy Board designed them, usually care of the Surveyors of the Navy and their assistants and draughtsmen. British ships were often copied from captured French vessels, whose designs were much admired and often considered superior to those of British ships. After the Navy Board and Admiralty approved a design, the draughts were copied for the shipyards. In cases where ships were built in private yards, the Navy Board had to seek out builders and negotiate the cost from various competing firms.

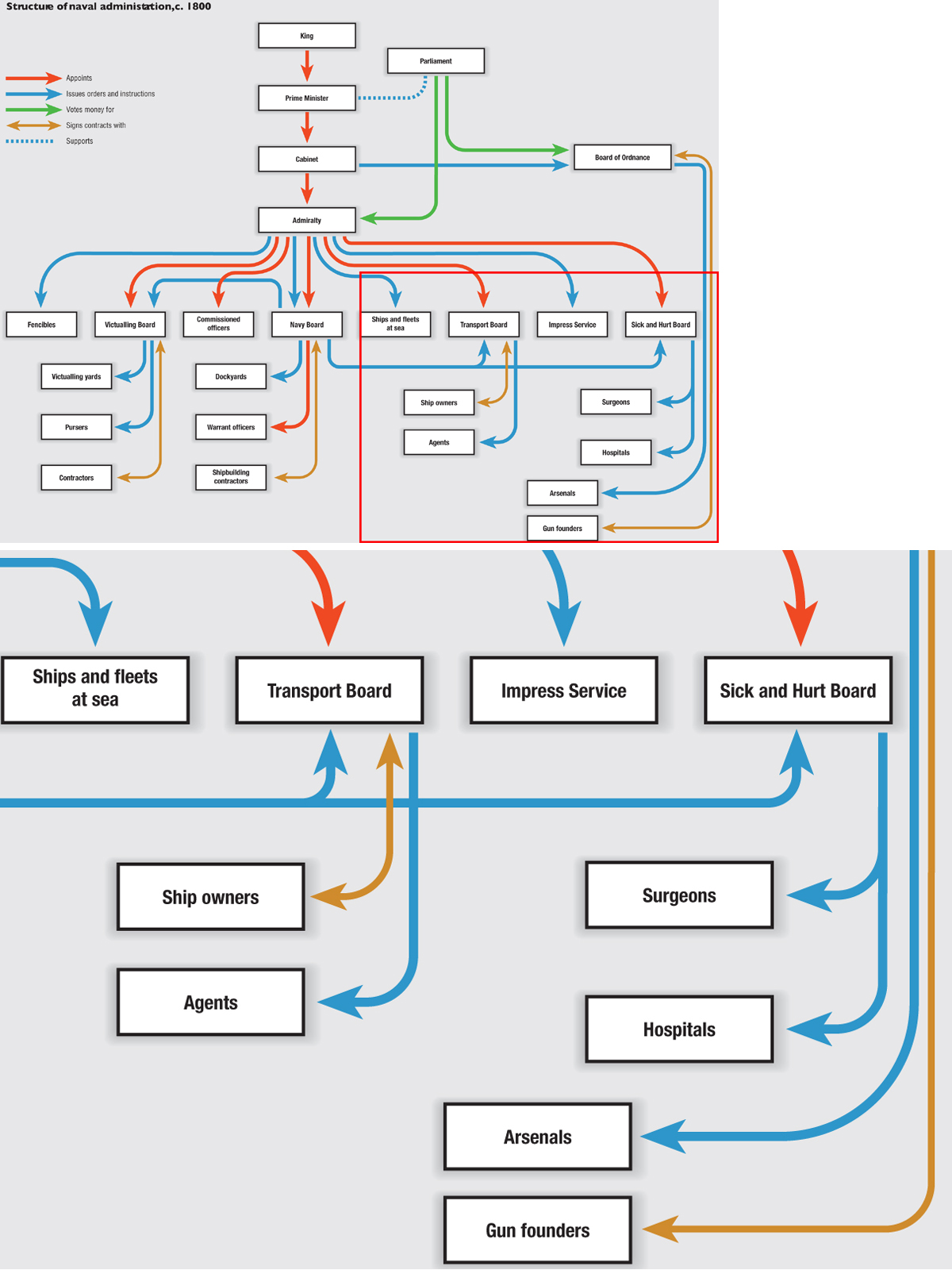

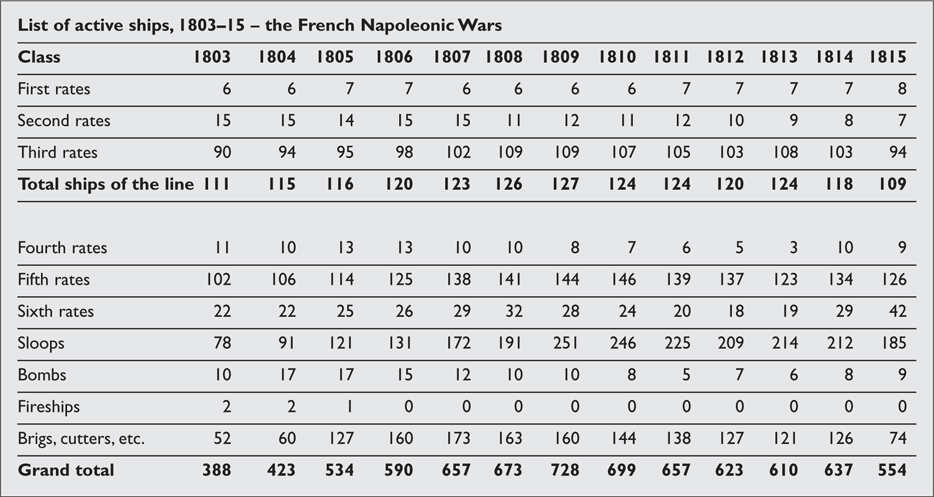

In the course of the wars the Navy Board built approximately 100 ships of the line and 700 smaller ships and craft, representing over half a million tonnes, plus other ships built overseas. The largest ships – the first and second rates – were constructed in the Royal dockyards, with the remainder built in private yards. The Board dispatched someone to monitor the construction of all the vessels, which were often built in various sites along the Thames. Shipbuilding required the skills of 11 types of trade, above all that of shipwrights who reached this senior position only after seven years of apprenticeship in design and construction. Building a ship was a major enterprise: six months were required to build a sloop, between two and three years for a two-decked ship, and several years for a three-decker. Even then, once it was ceremonially launched, a ship still required several months for the process of fitting it out, including the erection of masts and placement of rigging, sails, stores, guns and other matériel.

Three subsidiary boards worked under the Navy Board umbrella: the Victualling, Transport, and Sick and Hurt Boards, all of whose members were, like the Navy Board, appointed by the Admiralty. The Victualling Board supplied the Navy with food, drink and clothing, and appointed pursers to oversee the distribution of such articles aboard ship. It ran its own bakeries, slaughterhouses and breweries to meet the needs of the sailors, and had its own ships to convey provisions to the Board’s naval facilities at Gibraltar and elsewhere. The Sick and Hurt Board conducted examinations for surgeons, supplied their equipment, and managed the Navy’s hospitals. The Transport Board conveyed Army and Navy personnel aboard a combination of privately hired merchant vessels and Navy ships. The Transport Board was noted for its efficiency and ran between 40 and 50 storeships for the Navy alone, with many more used for the Army. In 1796 the task of managing prisoners of war passed into its hands from those of the Sick and Hurt Board.

The Board of Ordnance, a government department separate from the Admiralty and based in the Tower of London and at Woolwich, held responsibility for supplying all the Navy’s (and Army’s) armaments – everything from pistols and dirks to cannon. The Board ran the factories that manufactured powder and guns; it provided the transport to convey the munitions and arranged contracts for work through civilian firms. It also experimented with new types of guns and powders and made studies of existing weaponry. The Board of Ordnance not only maintained supplies, it also had responsibility for equipment already aboard vessels and in the dockyards. This meant liaising with ship’s captains to determine the condition of every weapon on his ship and the amount of shot and powder used, both during practice and in action. Guns and powder captured from the enemy had to be logged by captains, with the list of items sent on to London.

Proper functioning of this organization would not have been possible without a large number of officials and clerks, and the offices of the Board of Ordnance were lined with pigeon holes and boxes containing information in the form of lists and correspondence received from ships around the world concerning all the ordnance aboard every ship in the Navy. Every captain was required to account for the expenditure of all ammunition and shot, barring which he received a reprimand from the Board, wherever in the world he might happen to be.

At the beginning of the wars Britain maintained six dockyards, all run by the Navy Board. By 1815 these had launched 41 ships of the line and 78 other ships. About 60 private yards constructed another 60 ships of the line and over 600 other ships, some produced according to Admiralty design, others of the merchant yard’s design with the intention of selling the vessels to the Admiralty. Private yards of course also produced merchant ships, some of which the Admiralty chose to buy and convert for its own needs. In addition to ship construction, the Royal yards also had to provide workmen for the Navy and repair and maintain its ships. Royal dockyards were situated at Portsmouth – the largest in the country – Plymouth and Chatham. A naval hospital stood at Haslar, near Portsmouth, together with an ordnance depot, a gunwharf and a marine barracks. Chatham and Plymouth had similar facilities. Portsmouth, Chatham, Sheerness and Plymouth were all fortified and were situated near the main anchorages. Ships in service only docked in port for refitting or to allow their crews leave; otherwise they remained at their respective anchorages, offshore, from where they could put to sea with little delay. Ships operating out of the Nore watched the Dutch coast; those in the Downs covered the North Sea and the southern coast of Holland; the anchorages at Spithead and St Helens were bases for ships monitoring the Channel; and Torbay served as the station from which to watch Brest, Spain and the Atlantic. Ships based at Plymouth operated in the Atlantic and beyond.

The Royal Dockyard at Chatham, in Kent, which could cater for just about any ship’s material needs. Vessels ordered by the Admiralty were constructed according to plans based on a scale of 1:48. The keel was laid first, with the stem and sternposts attached and the frames erected to define the shape of the hull. Before the sides were planked with oak the frame of the ship was shored up to keep it vertical, and left to stand to season, sometimes for more than a year. In the course of construction and fitting out, a 74 required approximately 100 tons of ironwork, 30 tons of copper bolts, 12 tons of oakum, 5 tons of pitch, 12 tons of tar to coat the hull, 12 tons of copper sheathing and 4½ tons of paint. (Philip Haythornthwaite)

The possession of these establishments across the world not only enabled Britain to protect her trade and colonies but to harass those of her enemies. The relatively small extent of the Empire at this period reveals that the great age of British imperial expansion – a prominent feature of the mid- to late-Victorian era – had not yet begun. British possessions on the Indian sub-continent in the early 19th century were still largely confined to Bengal, which, like Canada, had been conquered during the Seven Years’ War (1756–63). Cape Colony, in southern Africa, was seized from the Dutch, a French ally, while New South Wales had been founded only a few years before the outbreak of war with France in 1793. Malta and Gibraltar, captured in 1800 and 1704 respectively, occupied key strategic positions in the western and central Mediterranean. Although extremely small in geographical terms, Britain’s West Indian colonies remained her most valuable overseas possessions, with sugar, slaves and rum generating vast wealth for the Treasury.

Dockyards in home ports could provide most of the needs of the Navy, but with its world-wide responsibilities the Royal Navy had to maintain bases across the globe. These facilities contained stores, food, depots for munitions, and equipment and materials for repairing ships afloat. In some cases medical care was provided, such as at Gibraltar. A civilian representative of the Navy Board oversaw the bases.

At the beginning of the wars in 1793 the Navy’s overseas bases were located at Gibraltar, Halifax in Nova Scotia, and Jamaica and Antigua in the West Indies, but these were added to throughout the conflict so that by 1815 British ships could defend all the nation’s principal trade routes. To supply the bases, the Admiralty bought naval stores in Britain and left their conveyance abroad to the ships of the Transport Board. The Victualling Board purchased food and drink for the use of the Navy, though supplies could be acquired locally when ships docked in foreign ports. As at home ports, the Board of Ordnance provided ordnance to British ports overseas, where ships repaired and replaced damaged weaponry.

HMS St Albans (64) being launched at Deptford, a private dockyard which supplied the needs of both the Navy and civilian commercial firms. Newly built ships in British yards were launched stern first, in contrast to vessels built on the Continent, and then towed away to be provided with masts and fittings elsewhere. The masts and yards for a third rate weighed about 70 tons, rigging and cordage a further 40 tons, cables and cordage about 44 tons, anchors 13 tons and sails eight tons. In addition to the various stores and equipment brought aboard a fully fitted ship, a 74 carried about 160 tons of ordnance, approximately 50 tons of ammunition and 350 barrels of powder. (Stratford Archive)

Various new ports were acquired during the course of the wars, two of the most important being in European waters. In the Mediterranean, the Army captured Minorca in 1798, thus enabling the Navy to use Port Mahon thereafter. When, however, peace with Spain was renewed in 1802 by the Treaty of Amiens, Britain restored the island to her erstwhile enemy. Port Mahon was of particular importance in enabling a fleet to watch the main French Mediterranean port at Toulon. Malta fell to British forces in 1800 after a two-year siege, providing the Navy with the invaluable port at Valetta, which was retained throughout the wars and formally acquired by Britain in 1814. The value of Malta as a base was recognized by many, including Admiral Lord Keith:

Malta has the advantage over all the other ports … that the whole harbour is covered by its wonderful fortifications, and that in the hands of Great Britain no enemy would presume to land upon it, because the number of men required to besiege it could not be maintained by the island … At Malta all the arsenals, hospitals, storehouses, etc, are on a grand scale. The harbour has more room than Mahon and the entrance is considerably wider.

In North America, the Navy had use of Halifax and Bermuda, at the latter of which construction of a dockyard began in 1809. Britain also had temporary use of Alexandria, Egypt, in 1801–02, and Ajaccio, Corsica, from 1794 to 1796. Lisbon was available from 1808 to 1814 as a result of the British campaign in the Iberian Peninsula. In the Caribbean the Leeward Islands Squadron used the base at English Harbour, Antigua, while the Jamaica Squadron used Port Royal. Martinique was under British control from 1794 to 1802 (like other colonial possessions, returned to France at the Peace of Amiens), and Curaçao was taken from the Dutch in 1807. Ships operating as far as India made use of the base at Madras and the East India Company’s dockyard at Bombay, which produced several ships purchased by the Royal Navy. In southern Africa, on the route to India, the Navy had access to Cape Colony with the fall of that Dutch colony to an expeditionary force in 1795. This was returned to Holland in 1802, but recaptured in 1806. One of the directors of the East India Company summed up the importance of this distant base:

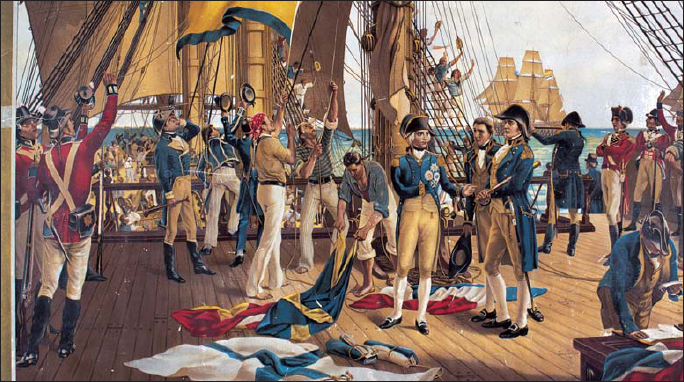

Horatio, 1st Viscount Nelson (1758–1805). Britain’s greatest admiral and perhaps the most accomplished naval commander of any era, Nelson typified the bold, resourceful, aggressive character of so many Royal Navy officers of the French Revolutionary and Napoleonic era. When the war began in 1793, Nelson was captain of the 64-gun Agamemnon and served in the Mediterranean under Lord Hood. He first came to prominence in February 1797 when he demonstrated his daring at the battle of St Vincent by first cutting the Spanish line and then boarding two ships in rapid succession. He was badly wounded in a failed attack on Tenerife later that year, but his injury did not prevent him from further service, and he rejoined the Mediterranean Fleet in the Vanguard (74). In 1798 Nelson utterly crushed the French at the battle of the Nile, bringing an end to Bonaparte’s dreams of an empire in the East. In April 1801 Nelson led the successful though costly attack against the Danish fleet at Copenhagen, adding further laurels to his reputation. The climax of his career proved, however, to be his apotheosis: victory over the combined Franco-Spanish fleet at Trafalgar on 21 October 1805 ended all realistic prospect of an invasion of the British Isles for the remainder of the Napoleonic Wars, but it cost Nelson his life. (Royal Naval Museum)

The importance of the Cape, with regard to ourselves consists more from the detriment which would result if it was in the hands of France, than any advantage we can possibly derive from it as a colony. It commands the passage to and from India as effectually as Gibraltar doth the Mediterranean; and it serves as a granary for the Isles of France; whilst it furnishes no produce whatsoever for Europe, and the expense of supporting the place must be considerable.

Communication at sea proved one of the most difficult problems to overcome in the age of fighting sail. Admirals could speak face-to-face with their captains from time to time, particularly before battle if time permitted, and written orders could be sent to the various ships in the fleet by summoning boats to the flagship to collect such orders. If vessels passed close enough messages could even be passed vocally through a megaphone, though this was not always possible. In any event, such forms of communication were slow and altogether impossible during enemy action. The alternative was the use of flags. Prior to the new system developed at the turn of the 19th century, signalling flags had specific meanings. This served commanding officers reasonably well throughout the 18th century, but flags were limited in their application to particular circumstances, foreseen during peacetime, yet not always practical during wartime.

Admiral Lord Howe invented a system that employed 14 different flags, each of a different design, which was added to the Signal Book of 1790. These included ten flags representing the numbers one through nine, plus zero. Each numerical flag had a particular meaning, while four further flags were used to signify ‘substitute’, ‘preparative’, ‘finishing’ and ‘affirmative’. Howe’s system could create approximately 260 messages, though over time these were expanded in number and the design of the flags improved.

The most effective system of signalling, however, was the product of Admiral Sir Home Popham, who realized that Howe’s system remained of limited value. In 1800, employing the same flags as Howe had used, he developed a system that came into immediate use. Popham’s system involved the use of a combination of flags to represent words and phrases that enabled captains and admirals to create thousands of words very rapidly. The main advantage, however, rested on the ability to expand the vocabulary for words not already represented by flags. Any word could be spelled out letter by letter by using a flag for each letter of the alphabet. So comprehensive was Popham’s system that when Nelson issued his famous signal, ‘England expects that every man will do his duty’, only the word ‘duty’ needed to be spelt out as individual letters.

The battle of Copenhagen, 2 April 1801, an extremely hard-fought action in which the North Sea Fleet fought a formidable combination of shore batteries and enemy ships of the line at anchor. (Philip Haythornthwaite)

In addition to their being used to pass the admiral’s orders, flag signals were employed for various purposes, particularly for conveying intelligence. Frigates were so placed around a fleet as to be in position to relay messages from one ship to another, to observe the horizon, and provide the admiral with timely warning of an approaching enemy. This was all very well in practice, but in reality a captain or admiral still had to decide up which mast his signal was to be hoisted to enable the recipient to see it clearly, considering the fact that the ships’ positions sometimes shifted owing to winds, currents, or the decisions of individual captains. Lookouts had to keep a keen eye out for signals, otherwise the sender had to fire a warning gun to attract their attention. At night, signals could be sent using a combination of guns, flares and lights, with approximately 70 messages available by these means. Of course, in the smoke of battle, in fog or where relaying frigates were not to hand, signals might go unseen or fail to be understood. In rare instances, signals were ignored, the most famous instance being when in 1801 Nelson chose to disregard Admiral Parker’s signal to withdraw from action during the battle of Copenhagen. Placing the telescope up to his blind eye, Nelson declared to the officers around him: ‘I have only one eye. I have a right to be blind sometimes. I really do not see the signal.’

As we have seen, Popham’s signal system was successfully employed at Trafalgar, and was the means by which Nelson’s famous signal was conveyed to the fleet, read in the following order:

Read down the mainmast

Read down the foremast

Read down the mizzen mast

Read down the peak, or gaff

Read down the starboard side of the mainmast

Read down the port side of the mainmast

Read down the starboard side of the foremast

Read down the port side of the foremast

Read down the starboard side of the mizzen mast

Read down the port side of the mizzen mast

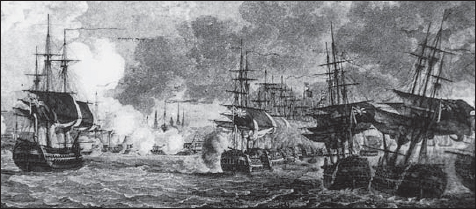

Admiral Lord Hotham’s action, 13 July 1795, off Hyères, near Toulon. In the course of watching Toulon with the Mediterranean Fleet, Hotham enjoyed only limited success, proving himself unable either to contain in port, or bring to battle in a decisive encounter, the French fleet. He managed to capture the Alcide (74), but shortly after she struck, this prize caught fire and blew up with the loss of her entire complement of 615 officers and men. (Stratford Archive)

Nelson’s famous signal at Trafalgar, 21 October 1805. (Royal Naval Museum)

By interpreting the flags in the foregoing order, other ships could discern the message as follows:

Mainmast: ‘2’, ‘5’, ‘3’: ‘England’

Mainmast: ‘2’, ‘6’, ‘9’: ‘Expects’

Foremast: ‘8’, ‘6’, ‘3’: ‘That’

Foremast: ‘2’, ‘6’, ‘1’: ‘Every’

Mizzen mast: ‘4’, ‘7’, ‘1’: ‘Man’

Gaff: ‘9’, ‘5’, ‘8’: ‘Will’

Mainmast (starboard side): ‘2’, ‘2’, ‘0’: ‘Do’

Mainmast (port side): ‘3’, ‘7’, ‘0’: ‘His’

Foremast (starboard side): ‘4’: ‘D’

Foremast (port side): ‘2’, ‘1’: ‘U’’

Mizzen mast (starboard side): ‘1’, ‘9’: ‘T’

Mizzen mast (port side): ‘2’, ‘4’: ‘Y’

As can be seen, however, the signalling system had its limitations; Nelson originally intended to say ‘Nelson’ rather than ‘England’ and ‘confides’ rather than ‘expects’, until his signalling officer, Lieutenant Pasco, observed that, as these words did not exist in the vocabulary, they would have to be spelled out, adding considerably to the number of flags required to make out the signal. Nelson readily agreed to the substitution, and the signal was duly transmitted with a manageable number of flags flying aloft.