British naval strategy imparted numerous responsibilities upon the Royal Navy, including the seizing of the enemy’s colonial resources, the defence of the nation from invasion and the protection of British supplies from overseas. Control of the sea was largely maintained by frigates, which could operate as reconnaissance vessels, perform convoy duty, and fight in ship-to-ship actions. Ships of the line did not cruise the seas in this manner, but rather performed blockade duty and, when possible, confronted the enemy in fleet actions. This, indeed, was a fleet’s raison d’être: to bring a rival fleet to battle and destroy it.

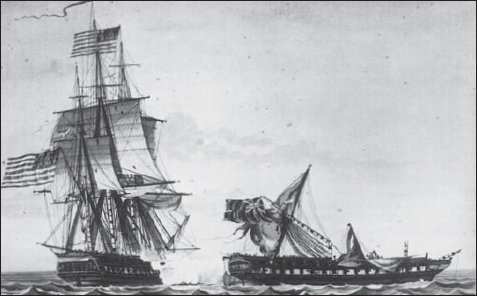

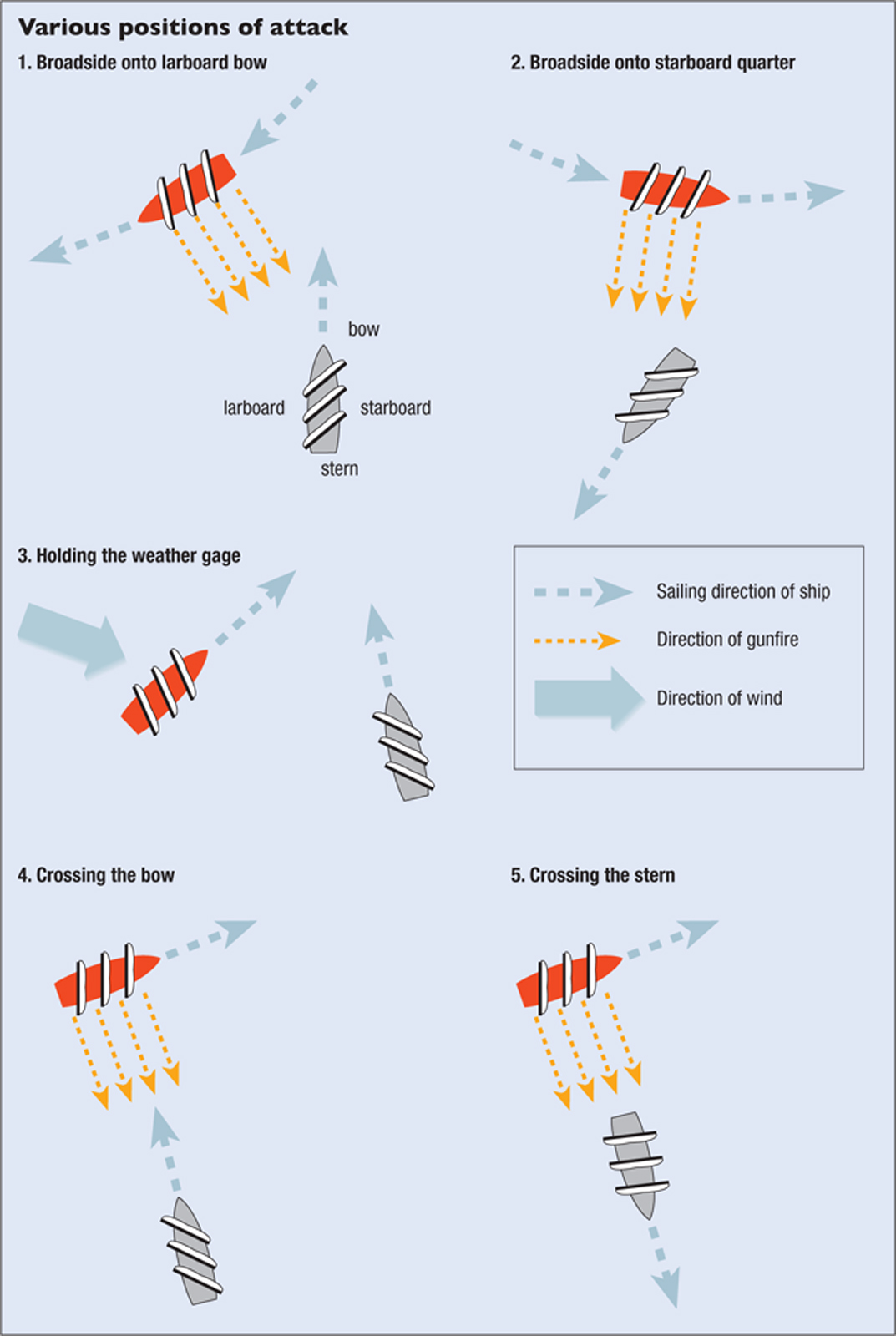

Once engaged with the enemy, general strategy gave way to the more technical art of tactics – the actual methods employed to defeat the enemy in battle. British tactics were based on the line of battle, which required an admiral to draw up his fleet in one or two lines, usually with the flagship in the centre and the frigates stationed on the unopposed side, so distributed along the line as to be capable of repeating orders from the flagship to the rest of the fleet before the engagement began. The enemy would also form a line, and the British attack would come either obliquely or in parallel, with, theoretically, every ship engaging an opponent of equal or weaker strength. By employing such tactics, the maximum strength of each ship’s broadside could be brought to bear. Prior to action, the admiral would already have decided whether he wished to attack with the weather gage or the lee gage. The side with the weather gage, by which the wind blew one’s force in the direction of the enemy, could almost invariably make contact with an opponent, whether he wished to engage in combat or not. The side with the weather gage also provided the attacker with the opportunity to double the enemy’s line (i.e. to attack him from both sides simultaneously) or pass through or break his line. On the other hand, the fleet with the lee gage could allow its weaker or damaged ships to leave the line when necessary. Moreover, the heel of the ship, which elevated the trajectory of the guns on the lower deck, allowed a vessel’s lower-deck ports to remain open longer, and provided more opportunities for firing on the enemy, the angle of whose opposing guns being depressed would not allow continuous fire. In short, a fleet determined to engage an enemy always favoured the weather gage, whereas a fleet seeking the lee gage normally did so to be sure of surviving an action, not least through the option of escape.

Nelson explaining his battle plan to his captains prior to Trafalgar, October 1805. (Royal Naval Museum)

| Enemy ships taken, burnt or sunk by the Royal Navy, 1793–1815 | |

| (Approximate number of vessels mounting four or more guns) | |

| French losses, 1793–1802 | 370 |

| French losses, 1803–15 | 310 |

| Total | 680 |

| Dutch losses, 1795–1800 | 90 |

| Dutch losses, 1803–10 | 40 |

| Total | 130 |

| Spanish losses, 1796–1802 | 65 |

| Spanish losses, 1804–08 | 60 |

| Total | 125 |

| Danish losses, 1801 | 15 |

| Danish losses, 1807–13 | 70 |

| Total | 85 |

| Russian losses, 1808–09 | 4 |

| Turkish losses, 1807–08 | 13 |

| American losses, 1812–15 | 12 |

In most of the major actions of the French Revolutionary and Napoleonic Wars the British sought to break or otherwise disrupt the enemy’s line, and therefore sought the weather gage. Contrary to popular belief, the notion of breaking the enemy’s line was not original to Nelson, nor even a product of the wars in which he fought; rather it originated with Admiral Rodney who, at the battle of the Saintes in 1782, penetrated the French line in an unprecedented feat later repeated in similar style at the Glorious First of June (1794), Camperdown (1797), St Vincent (1797) and, of course, most famously at Trafalgar (1805). In all these instances British tactics were invariably aggressive, with admirals and captains taking the initiative to attack, confident that their better-trained crews, even when faced by a numerically superior foe, would carry the day.

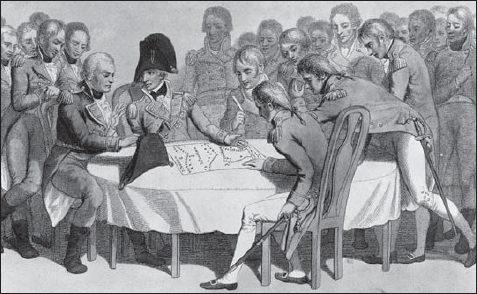

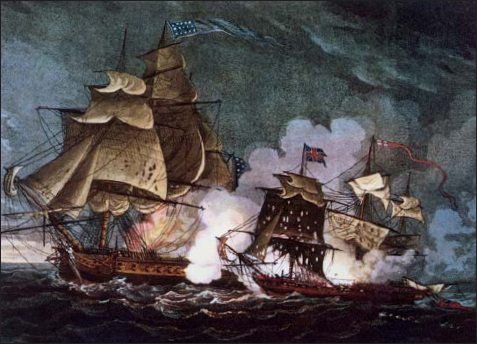

HMS Java (38) fights USS Constitution (44), on 29 December 1812, off Brazil. After a two-hour engagement, the wrecked Java struck her colours. (Stratford Archive)

1) Fleet in line of battle. This was the standard formation for attack, with each ship of the line (so-called because it was large enough to fight in the line of battle) drawn up bow to stern. The flagship, bearing the commander-in-chief, was positioned at approximately mid-point in the line to enable its signals to be seen clearly by the ‘repeating’ frigates. These were positioned to windward, so poised to be able to repeat the signals for the benefit of all the ships in the fleet.

2) The fleet to windward enjoyed the advantage of being able to choose the approximate time and point of attack. Here, the windward fleet approaches in an attempt to manoeuvre around the head of the enemy’s line, so forcing it to accept battle.

3) The windward fleet attempts to engage an enemy which, positioned to leeward, has the option to avoid battle by turning away and fleeing with all its sails deployed.

4) The windward battlefleet successfully engages the enemy fleet, which is sailing to leeward.

5) Breaking the line. The attacking fleet passes through the opposing line in order to engage the enemy on both sides – a manoeuvre known as ‘doubling’. This tactic was employed successfully by the British fleets at the Saintes (1782), St Vincent (1797) Camperdown (1797), the Nile (1798) and Trafalgar (1805).

6) Isolating the van. Having passed through the opposing line, the attacker isolates the enemy van, thus preventing him from escaping to leeward.

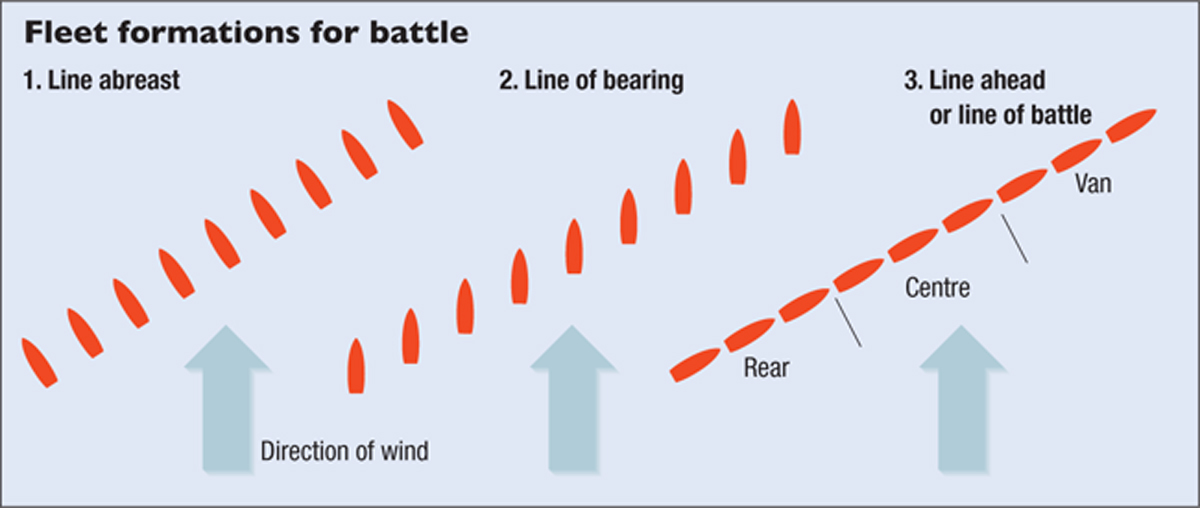

1) Line abreast was often adopted in waters where the presence of an enemy fleet was considered remote. Still, patrolling frigates positioned around the fleet performed the task of reconnoitring to ensure that an admiral was not caught unawares.

2) Line of bearing enabled ships both to communicate easily with each other and to form into line ahead with a minimum of time and effort.

3) Line ahead (also known as line of battle) had since the mid-17th century remained the standard method of deploying ships of the line preparing to engage the enemy. By the end of the 19th century, however, bolder, more innovative commanders such as Nelson had begun to depart from the Admiralty’s official Fighting Instructions in order to break the enemy line and fight what he called a ‘pell-mell’ battle; that is, pitting individual ships against one another in scattered positions, relying on superior British gunnery and discipline to decide each contest and thus achieve a successful outcome for the battle as a whole.

1–2) Broadside onto larboard bow and broadside onto starboard quarter. As shown here, vessels able to bring to bear their full broadside against an enemy whose position limited his own field of fire, enjoyed a significant tactical advantage. Thus, with skillful manoeuvring an attacker could maintain such a position – more often in a ship-to-ship, rather than in a fleet, action – so crippling an enemy whilst sustaining relatively little damage in return. It was precisely in such circumstances where superior seamanship, as opposed to superior gunnery, often told.

3) Holding the weather gage. A vessel so positioned enjoyed the advantage of determining the approximate time and place of engagement, though it could not usually prevent the enemy from avoiding battle if he so desired.

4–5) Crossing the bow and crossing the stern. These were the most effective positions of attack, especially the latter. Also known as crossing the ‘T’, this position enabled the attacker to fire with virtual impunity against the most vulnerable parts of the enemy vessel, above all the stern windows of the opposing captain’s cabin. Round shot fired along the length of an enemy’s lower decks inevitably caused frightful havoc, overturning guns and bowling over men like ninepins.

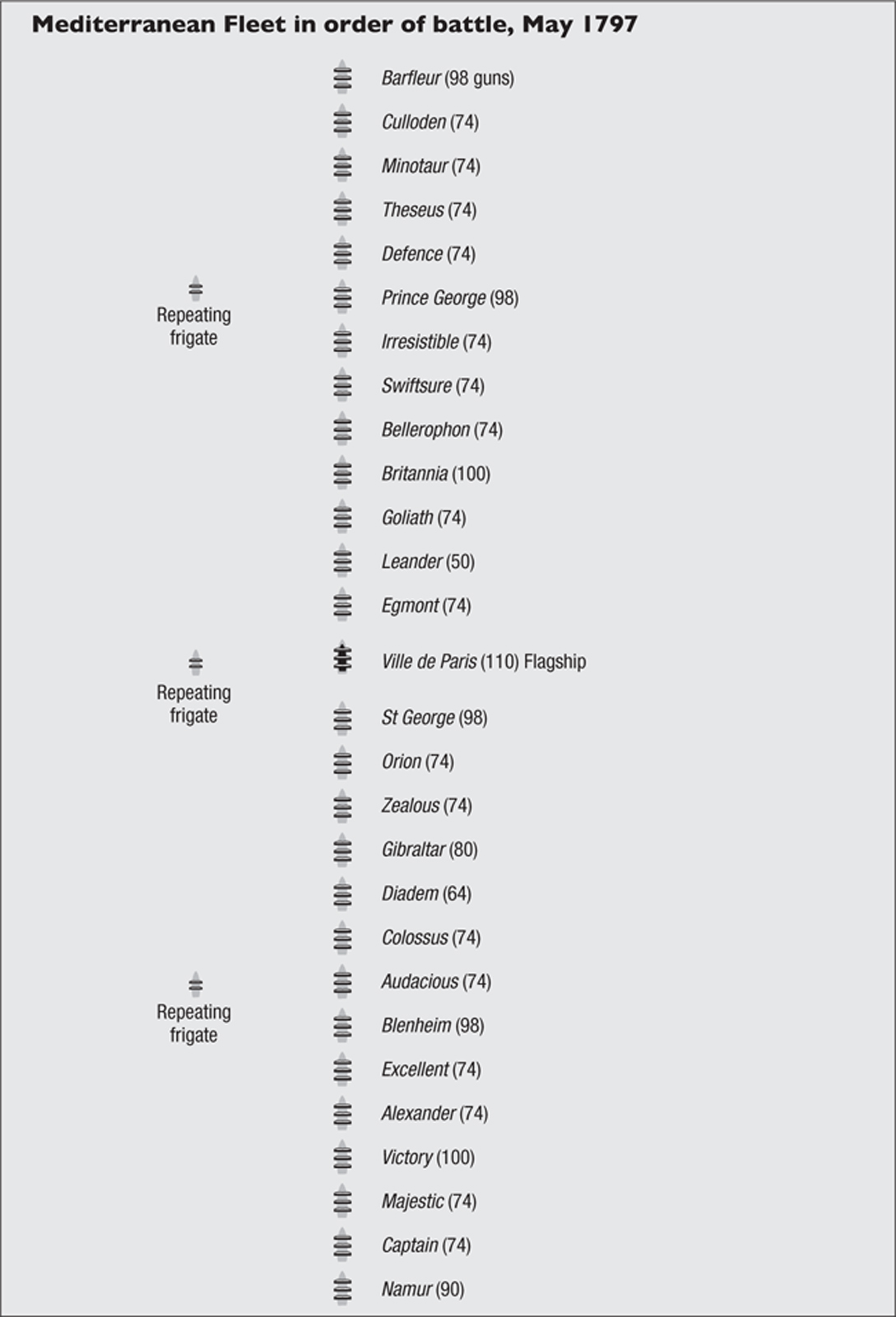

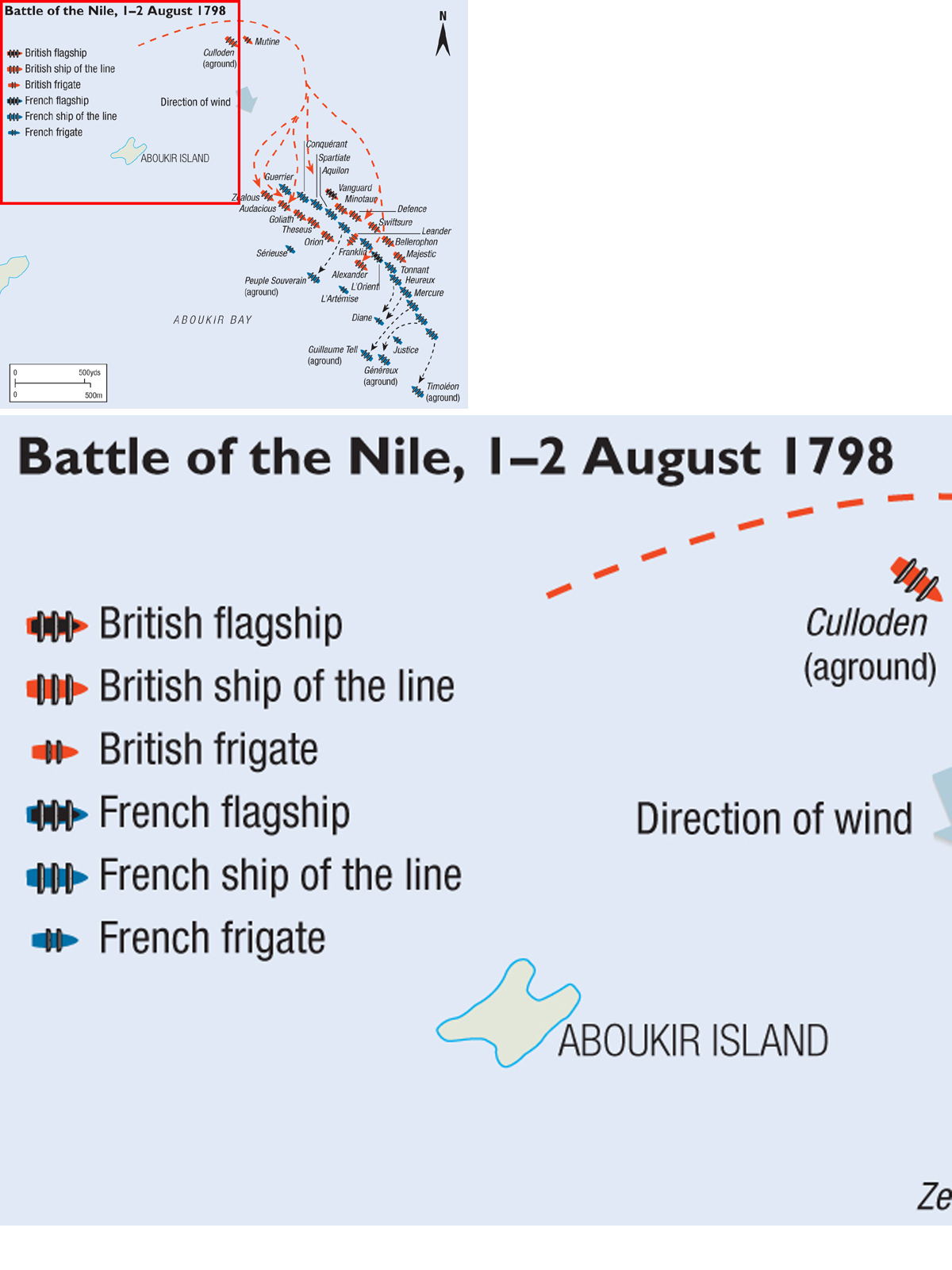

The battle of the Nile was fought in Aboukir Bay on the Egyptian coast, approximately 15 miles east of the mouth of the Nile. Admiral Brueys, commanding the French Mediterranean Fleet, chose this open anchorage for his 13 ships of the line and four frigates, secure in the knowledge that his position was, if not unassailable, at least strong enough to prevent the British from dislodging him. Specifically, he deployed his ships in a close line near to a shoal, with his weaker van protected by a six-gun battery situated on a nearby island and his strongest vessels composing the centre and rear. His brigs and frigates, together with gunboats and bomb vessels, sat on the landward side where it was presumed they would enjoy protection from an attacker. This deployment seemed the most sensible option given the shape and depth of the harbour; indeed, it ought to have been had Brueys been opposed by a less intrepid opponent, for no sooner had Nelson entered the bay than he was advised by one of his captains of a fundamental flaw in the French defence.

This shows the standard formation in battle, line ahead, the most effective means by which ships could bring their guns to bear against the enemy. Once engaged, however, such pristine formations could not necessarily be maintained, for damage, the enemy’s movements, new signals from the commander, and the general chaos of battle could throw a battle line into disarray.

Crucially, Brueys had been at anchor for a month and was not aware of Nelson’s approach. As a result, hundreds of his men were ashore collecting water for the fleet. Nor did Brueys expect Nelson to attack so late in the day or believe his opponent’s ships could negotiate the shoals that partially protected the opening of the harbour. In addition, dusk was already looming when the British fleet went into action – further cause for Brueys to assume Nelson would not attack until the following day. The French were also unprepared on their landward side, on the basis that their commander thought it impossible for the British to double his line owing to the shoals – the flaw identified by the British. Brueys did manage to clear for action on his starboard (i.e. seaward) side, but his captains had time before the British attacked around 1830hrs neither to put springs on their ships’ cables – a procedure that would have enabled them to swing themselves into new positions – nor to bring up their stern anchors. The French were thus forced to fight in a static position and could do nothing to prevent the British from engaging from the landward side – a position thought to be too shallow for a ship of the line to negotiate.

Not only were the French crews under strength, but they had also stacked boxes, barrels and crates on the landward side of their decks, making it, at least initially, impossible to handle the guns on the port side. Appreciating that the enemy rear was in no position to assist the centre and van, Nelson concentrated his initial attack on only a portion of the French line, bringing for this purpose 13 ships (the fourteenth, HMS Culloden, had grounded on a shoal at the mouth of the harbour and took no part in the action) to engage only eight French. This numerical advantage, compounded by the superior rate of fire of the British crews, enabled Nelson to overwhelm each enemy ship in turn, and move successively down the line, disabling and capturing more vessels after fierce exchanges of fire. Not only could the ships composing the French rear offer no assistance to their consorts further up the line, but most of these eventually succumbed to the British onslaught, with only two ships of the line and two frigates managing to escape.

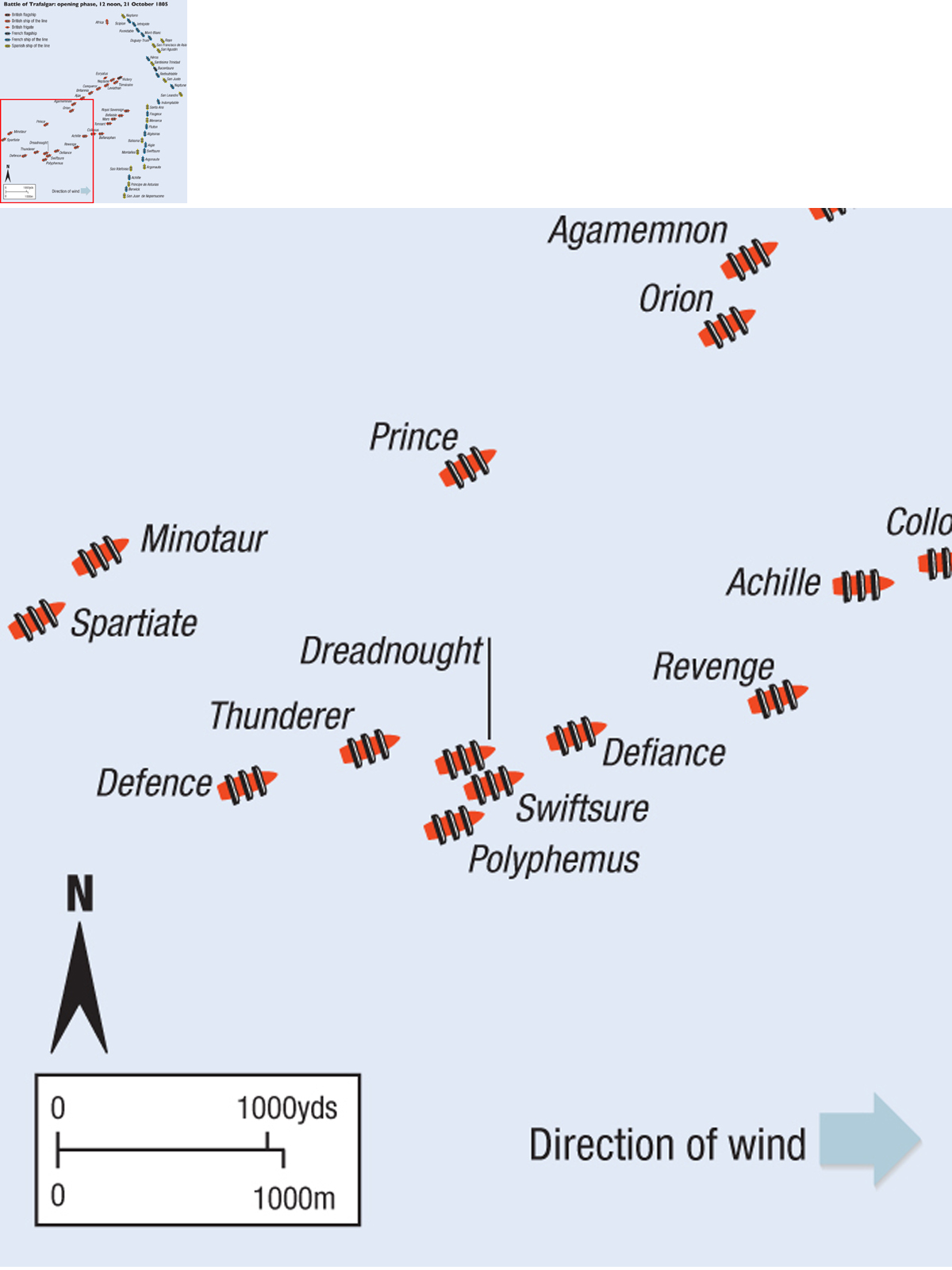

At Trafalgar – unlike at the Nile, fought in the open sea – Nelson divided his fleet into two roughly equal-sized columns, one of which was to separate the Franco-Spanish centre and rear from their van. The other would pierce the enemy line through its centre. By doing so, the van would be unable to support its consorts without coming about – a process that could take so long that the battle might already be lost. By isolating the van, Nelson not only compensated for his own numerical inferiority (33 Franco-Spanish ships of the line to his 27), but also could then himself outnumber his opponents in the centre and rear. This form of attack entailed a certain degree of risk, however: the leading vessel of each column, by sailing directly against the enemy’s broadsides, would receive fire against its stern without any means of reply until the line was reached. In the event, the Victory and the Royal Sovereign reached the enemy line without injuries serious enough to prevent them from passing through Admiral Villeneuve’s line, against which a whole succession of British ships issued devastating broadsides while crossing the enemy’s ‘T’.

Once both columns broke through, Nelson relied on individual captains to engage the enemy’s ships and capture or destroy them through superior gunnery, morale, discipline and seamanship. The admiral knew that once battle was joined, issuing new signals would probably be of little use, for they would probably be unseen in the smoke and confusion. It was for this reason that Nelson issued instructions which covered all contingencies: ‘In case signals can neither be seen nor perfectly understood no captain can do very wrong if he places his ship alongside that of an enemy.’ As expected, the fighting then developed into a series of ship-to-ship encounters – what the admiral called a ‘pell-mell’ battle – including several unsuccessful French attempts to board the Victory and other vessels. Very belatedly, the Franco-Spanish van attempted to wear and come to the assistance of the centre and rear, detaching ten vessels for the purpose. Ships from Collingwood’s column, however, prevented Admiral Dumanoir Le Pelley from rescuing a hopeless situation by interposing themselves between the shattered centre and rear and the as yet unengaged Franco-Spanish van. The resulting British victory was nothing if not decisive: 18 enemy ships of the line captured or destroyed – more than half Villeneuve’s force.

The battle of Trafalgar, 21 October 1805. Nelson, with 27 ships of the line, smashed the combined Franco-Spanish fleet of 33 vessels in the most decisive naval encounter in modern history. (Umhey Collection)

The battle of the Nile, 1–2 August 1798, the most decisive naval encounter of the 18th century. In very few engagements, whether on land or sea, may one side genuinely be described as having been annihilated. At the Nile, British tactics proved so effective as to trap all but a handful of French vessels within the narrow confines of Aboukir Bay, with the opportunity for escape passing before the course of the battle turned – virtually from the outset – decisively in Nelson’s favour.

Nelson chose to attack with two divisions of approximately equal strength, driving through the Franco-Spanish line in order to isolate and defeat the centre and rear before the van could make the wide turning movement required to enable it to assist its beleaguered consorts to the south. The British could rely with confidence on the notion that, once evenly matched in numerical terms because of the isolation of the enemy van, their ships would overwhelm their opponents in the inevitable slogging match that would develop once the Franco-Spanish line had been broken. Nevertheless, the line of approach adopted by the columns under Nelson and Collingwood, respectively, exposed their leading vessels to considerable danger, for whereas the defenders could concentrate their full broadsides against the bows of their attackers, the British could offer no reply until they reached the enemy line.

Men clinging to wreckage and fallen rigging during the battle of Trafalgar. Notwithstanding their intimate connection with the sea, very few sailors could actually swim. (Philip Haythornthwaite)

The brig HMS Little Belt and frigate USS President exchange fire, 16 May 1811, more than a year before hostilities broke out between the United States and Britain. Commodore John Rogers of the President had been sent to cruise off New York to prevent British ships from stopping and searching American vessels in pursuit of British seamen seeking to avoid service in the Royal Navy. Rodgers pursued and confronted the Little Belt but could not make contact until darkness had fallen. The British sloop refused to identify herself, whereupon a shot was fired – neither side laying claim to it – and a 30-minute action ensued, leaving 11 British dead and 21 wounded, to the Americans’ single injured ship’s boy. While Rodgers himself expressed regret for the action, his countrymen and government were growing increasingly irritated by the impressment of American citizens by Royal Navy captains. (Stratford Archive)

The classic naval encounter between the 38-gun HMS Macedonian and the USS United States (44) in October 1812 as described by Samuel Leech gives a good impression of how a ship prepared for battle and actually fought.

A lookout high in the rigging, possibly perched on one of the tops (a platform fixed up each mast), indicated the presence of another vessel with the words, ‘Sail ho!’. The captain immediately came on deck and called for the direction of the strange ship and enquired into its nationality. On hailing the lookout again, after a few minutes passed, he received the information he required. Once it was identified as an enemy – in this case an American – ship, the captain issued his command and the ship was readied for battle:

All hands clear the ship for action, ahoy! The drum and fife beat to quarters; bulk-heads were knocked away; the guns were released from their confinement; the whole dread paraphernalia of battle was produced; and after a few minutes of hurry and confusion, every man and boy was at his post, ready to do his best service for his country …

To ensure that every man remained at his respective station, the junior midshipmen were told to shoot anyone who deserted his post. The guns were loaded and the slow matches lit, in case the matchlocks misfired. A proportion of the men were then allocated the task of making up a boarding party, should one be required. Leech then described how:

A lieutenant then passed through the ship, directing the marines and boarders, who were furnished with pikes, cutlasses, and pistols, [and told] how to proceed if it should be necessary to board the enemy. He was followed by the captain, who exhorted the men to fidelity and courage, urging upon their consideration the well-known motto of the brave Nelson, ‘England expects [that] every man [will] do his duty’.

The men in the tops, usually responsible for working the sails, were issued with small arms so as to direct fire down on the enemy. Below, on the main deck, Leech was stationed at the fifth gun, where he was responsible for ensuring that his gun was supplied with powder by running up and down the ladders to and from the magazine with cartridges covered by his jacket. The ship was then manoeuvred to enable the starboard guns to come into action, with a telltale sound indicating the start of the engagement. Leech recorded that:

HMS Guerriere (38) v USS Constitution (44) one of several epic frigate actions fought during the Anglo-American War (1812–15). Contrary to popular belief, guns were not fired simultaneously as one thunderous broadside, except perhaps for the opening salvo, for the shock to the ship and crew would be extremely great. Guns were normally fired on the orders of individual gun captains who timed ignition according to the moment during the constant roll of the ship when their guns came to bear on the enemy. (Stratford Archive)

A strange noise, such as I had never heard before, next arrested my attention; it sounded like the tearing of sails, just over our heads. This I soon ascertained to be the wind of the enemy’s shot. The firing, after a few minutes’ cessation, recommenced. The roaring of cannon could now be heard from all parts of our trembling ship, and, mingling as it did with that of our foes, it made a most hideous noise. By-and-by I heard the shot strike the sides of our ship; the whole scene grew indescribably confused and horrible; it was like some awfully tremendous thunder-storm, whose deafening roar is attended by incessant streaks of lightning, carrying death in every flash and strewing the ground with the victims of its wrath; only, in our case, the scene was rendered more horrible than that, by the presence of torrents of blood which dyed our decks.

Throughout the fight Leech heard the cries of the wounded all around him – some men dismembered by shot and others disfigured by flying splinters. The wounded were carried below to the cockpit, the dead heaved overboard. One of the powder monkeys was severely burned in the face when a cartridge in his hands caught fire. ‘In this pitiable situation,’ Leech wrote, ‘the agonized boy lifted up both hands, as if imploring relief, when a passing shot instantly cut him in two.’ One of the other members of the gun crew lost his hands to a passing shot, followed by a second which opened his bowels. With no hope of survival, he was thrown overboard by his comrades:

Such was the terrible scene, amid which we kept on our shouting and firing. Our men fought like tigers. Some of them pulled off their jackets, others their jackets and vests; while some, still more determined, had taken off their shirts, and, with nothing but a handkerchief tied round the waistbands of their trowsers, fought like heroes.

Men aboard ship, frightened though they might have been, had no means of escape from the combination of shouts, screams, smoke and the roar of gunfire. There was little choice but to carry out the tasks for which they had been trained, as Leech further observed:

We all appeared cheerful, but I know that many a serious thought ran through my mind … To run from our quarters would have been certain death from the hands of our own officers; to give way to gloom, or to show fear, would do no good, and might brand us with the name of cowards, and ensure certain defeat. Our only true philosophy, therefore, was to make the best of our situation by fighting bravely and cheerfully.

Soldiers and sailors throughout history have sought protection in battle through prayer. Even those, like Leech, who had no particular religious dispositions, still sought divine intervention when faced with the imminent prospect of death:

I thought a great deal … of the other world; every groan, every falling man, told me that the next instant I might be before the Judge of all the earth. For this, I felt unprepared; but being without any particular knowledge of religious truth, I satisfied myself by repeating again and again the Lord’s prayer and promising that if spared I would be more attentive to religious duties than ever before. This promise I had no doubt, at the time, of keeping; but I have learned since that it is easier to make promises amidst the roar of the battle’s thunder, or in the horrors of shipwreck, than to keep them when danger is absent and safety smiles upon our path.

As fate would have it, her American adversary easily outgunned the Macedonian, and Leech, together with the remainder of the crew, was taken prisoner.