16

Just a few days ago, I would have called you crazy for saying I’d miss Christopher Haines for any reason, but I’m not looking forward to a three-hour ride home from Yosemite with just Mom. Though the last day or two of vacation was at least a nominal cease-fire, Mom still hasn’t given up the idea that she should organize my life as well as she organizes the spices in the cabinet at home. She’s been bugging me about finding an internship again, asking what plans Topher has for his life, and even asking me if I ever heard Simeon talk about what he wanted to do in life, as if she can subtly discover his whereabouts.

In the car, I brace for another round of Vivianne Seifert’s Twenty Questions, but Mom surprises me this time by not asking me anything. She puts on the stereo and we listen to, ridiculously, a relaxation CD, bubbling brooks interspersed with wafting flutes. By the time we’re out of Yosemite Valley, it’s like water torture. I need a bathroom, and I’m fighting back giggles.

“Mom. Are you tense? ’Cause all this water makes me have to pee.”

Mom’s mouth twitches. “Sorry. I thought it would help.”

I find myself smiling. “Thanks…. But I don’t need any ‘help.’ I’m fine.”

Mom flicks a glance at me sideways. “Are you?”

“Not really, but who is?” I shrug. “It’s just life, Mom.”

“Can we talk about it?” my mother asks gently. And then her phone rings.

“Answer it.”

Mom gives me an incredulous look. “Not on your life! Lainey, you are far more important to me than anyone on the other end of that line. Believe me, it can wait.”

“But…” I don’t really have anything to say. “It’s nothing, Mom. Answer the phone.”

For a moment, Mom’s shoulders slump, but then she straightens. “I’m going to keep asking, Lainey,” she says. “I’m asking because I love you.”

“I know, Mom,” I say. “Answer the phone.”

Mom sighs and punches the button to activate her headset.

I’m relieved. I don’t want to talk to Mom anymore about Simeon. She’s going to say he wasn’t a good influence for me or something like that, that I’m a “great girl” and I’ll find someone who meets my high standards, blah blah. The thing is, his leaving still hurts, and what Topher told me hurts worse. I’m just not ready for the “lemons make lemonade” pep talk yet.

Mom stays on the phone all the way home. For the first time, I realize how much she’s put off to spend time with me. There are restaurant people and wedding coordinators and others who have left messages for her already today. There’s a food magazine that wants a shot of a certain dish and needs to schedule people. In between calls Mom’s been making voice memos to herself about things to do later. Once, I clear my throat, and she stops talking to glance at me.

“Did you want to say something?”

“Umm…no.”

A sigh. “Laine? Is there a specific reason you don’t want to talk to me?”

My stomach twists. “You want to fix everything…. Plus, you don’t like him.”

“I didn’t know we were talking about ‘him.’” She says it mildly, but I still react.

“We’re not. But…I don’t want you to say ‘I told you so.’”

A pause. “When have I ever said that I don’t like Simeon?”

“Well, you don’t. You acted like I was wasting my time by being friends with him.”

Mom sighs and changes lanes. “Remember when I told you that a great girl like you would find all kinds of people to appreciate her someday? I meant that. Elaine, it’s never a waste to be a friend to someone, and I’ve never objected to you being a friend to Simeon. What I’ve objected to is you pretzeling yourself around what he wants to the point that you’re cutting me off and changing who you are.”

“I haven’t changed,” I say defensively. “I’m the same person I always was.”

“So this time last year you were someone who lied to me and withdrew from my bank account without telling me? No. Don’t you see? Lainey, you compromised my trust. You put Simeon’s wants above your own knowledge of what was right. And now”—she grimaces—“you keep wondering why I can’t get past it. You know why I can’t? Because I don’t think you understand yet how serious this was. What else are you willing to do for a friend, Elaine? How much are you willing to give away?”

There’s an uncomfortable silence. Mom breaks it.

“I love you, Lainey. You know I do. And I’m sorrier than you know that Simeon is gone and there’s no resolution for you. I won’t say I’m not relieved you’re no longer involved with him, but it’s not about him, Lainey. My concern is all about you.”

Was that an “I told you so”? Or did I already know that?

It’s the last week for pea shoots. Mom, Pia, and the sous-chef have discussed changing some items on the menu to later-spring dishes, like grilled vegetables, but I still find myself with a sink full of the delicate greens, washing them carefully. I feel like I’ve been standing elbow deep in water for the last week, but I’m happy to be back in the kitchen.

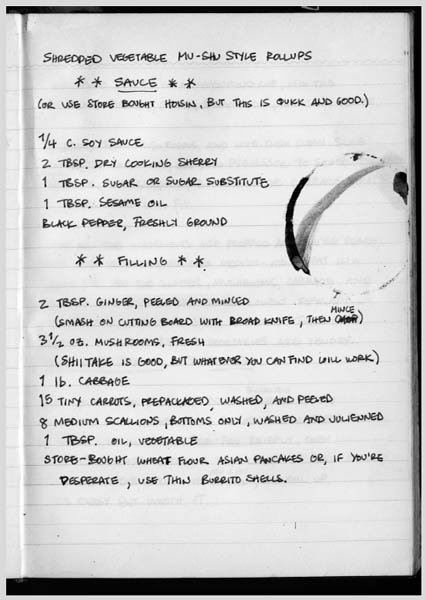

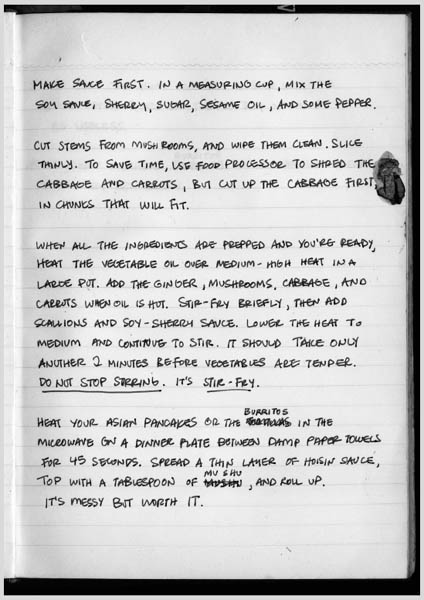

Mom decided that I don’t need to check in with her at the restaurant anymore, but I’ve been coming in every evening anyway, mostly because being alone in the house gives me too much time to think. I stay up late and sleep in. I watch reruns of Baking with Julia, and I flip through my notebooks, Mom’s cookbooks, and all my food magazines to find something new to create every day. I even make a time-consuming mu shu, from the thin pancakes to the filling to the sauce. There are still too many hours to fill.

There hasn’t been any word from Simeon, and the number I had for him has been disconnected. The gray spy car wasn’t here when we got home. It’s like he no longer exists. I don’t know what to think.

Every night, I walk, taking a roundabout way to La Salle, and try to get everything out of my system. It’s really starting to hit me that I have nothing to do, no one to try to organize but myself. I’m slowly starting to take the idea of an internship seriously. I’ll probably need to find a paying internship, since I doubt I’ll see Simeon again with my money, and Mom’s account isn’t open to me anymore. Suddenly the shape of the future looks really, really different, and I don’t know how I feel about it. Life—real life—is approaching fast.

I walk with quick, determined steps, and I’m a block past the hospital before I start to slow down. It’s a warm night in San Rosado. People are just getting home from work, and there’s a banner over the road, between Sophie Lane and Mulberry, advertising the First Street Festival to coincide with the farmers’ markets again this season.

There’s a crowd in front of Copperfield’s, sitting at the open-air tables and chatting. I can smell coffee mingling with the harsher smell of smoke as people unwind with their newspapers and cell phones. A bunch of guys look like they’re actually playing some kind of board game while they’re drinking their coffee. A huge pair of dice with something like fourteen sides clatters off the table. One of the guys dives into my path to grab it.

“Sorry.” I give him a half smile and keep going. He’s kind of cute, in a completely mad-scientist, antisocial way, but it makes me depressed that he’s outside on a nice evening playing a game with a bunch of geeky guys. Where’s the romance in the world?

There’s a vendor in front of Soy to the World, selling tie-dyed scarves and dolphin toe rings. I sidestep her warily. All I need is someone trying to talk to me about peace and love. I know my walk is turning into a pity party, but I can’t help it. I feel like everything that could unravel with my life has.

Everywhere I look, there are people wandering out in the balmy evening air, looking happy with their world and completely absorbed in their friends. The library is having a used-book sale, and I stop for a moment to browse. I’m always on the lookout for old cookbooks. I flip through a few, then sigh and keep walking. Even cooking doesn’t seem worthwhile.

Tonight the restaurant seems foreign to me. I feel like I’m in the way. Mom and Pia are busy, running around and making special orders. Ming asked if I’ve found my internship yet, and Gene wanted to hear about my college choices, but things got busy when a huge party came in and everyone had to move tables and recheck the menu to accommodate food allergies. One of the diners is allergic to lettuce. Seriously.

By the time the rush is over, I’ve paced Mom’s office like a caged panther, gone down to the kitchen twice to watch everyone running around, and refused a plate when Pia offered me one, and now I’m standing at the back door, watching the little slice of sky visible from the alley where the busboys take their smoke breaks. The clouds have rolled in. It’s threatening to rain or at least get unpleasantly foggy and make my hair frizz up all over my head.

My mother appears next to me and puts her hand on my shoulder. The two of us stand quietly, watching the storm come.

I keep hearing what Mom said to me, about how much I’m willing to give away to keep a friend. Was I willing to trade her? Was she just being overdramatic? I’d like to think so, but I remember how I felt when I thought Simeon needed me. When I start thinking that Mom’s got it all wrong, I remember how good it felt, how much it filled me, and then I wonder…is she right?

The first week back to school always sucks, but this first week of the last grading period is really “craptacular,” as Cheryl says. For one thing, it’s the beginning of senior countdown, and all I see everywhere is signs about the prom, the Last Dance, which is Redgrove’s cheap and casual all-school party for those who can’t afford the prom, and all final projects, final tests, and final everythings. The eight weeks ahead loom like an overstuffed burrito; niceties like time to sleep, put on makeup, or eat seem to have fallen messily by the wayside. Every night that I’m not at the restaurant, I’m at a tutoring session for either physics or trigonometry.

The good news is that I got into the California Culinary Academy in San Francisco, starting in the summer if I want it or fall if I don’t, and I got in at Mills College with an “undeclared” major, and I’m wait-listed for UC Berkeley. The bad news is, our teachers keep saying that acceptance letters are no guarantee if our grades tank these last few weeks, so I know I’d better keep on top of things. When I find out that Cheryl is a tutor for English lit, I wonder briefly what it would take to bribe her into writing my last paper for me. Cheryl just laughs when I ask her.

Vocal Jazz has added even more urgency to life with an impending performance. Our upcoming spring show means that zero period turns into boot camp each morning and Ms. Dunston puts us through our paces.

The second week after break, I get a letter from the Just Tomatoes contest I entered. It is polite, a “thank you for taking the time to enter our contest, your entry was very creative” type of form letter, but a rejection is a rejection no matter how nicely they put it. This is kind of the last straw. I am so depressed I don’t even go to the gym, even though I know the corn bread I baked from scratch for last night and the bag of kettle corn I bought at the cafeteria snack shop on Friday have made themselves at home in my body somewhere. What makes it worse is that the kettle corn didn’t even taste all that good.

As is the tradition at Redgrove, the seniors “surprise” Ms. Dunston at our last Vocal Jazz rehearsal before the show. One of the tenors, who went to Hawaii with his family for break, brings a two-pound box of chocolate-covered macadamia nuts. Ms. Dunston opens the box at the end of class, and I am feeling so crappy I eat three pieces. There are 204 calories in an ounce of plain macadamia nuts. I don’t even want to know how many calories there are if you add chocolate. I only hope I can fit into my Jazz uniform one last time.

Backstage at the spring show Friday night has the feel of the kitchen at La Salle. Between numbers, the jazz band plays swing music, and we can hear the audience applauding soloists, dancers, and instrumentalists. Every few minutes some minor drama breaks out, and hysterical giggling is shushed or someone starts sniffling or rushes off to the bathroom. The theater girls, in copper satin dresses, are clustered in front of mirrors, pinning fake white roses in their hair for the final piece. The Vocal Jazz group, the girls in hideous teal dresses and the guys in matching vests, is just getting ready for its cue. We’re holding no music, no props, nothing. Our final performance is like a prix fixe menu, a smorgasbord of the year’s performances, and only Ms. Dunston, chic in a little black dress with diamond pins in her hair, knows what our encore will be. This performance counts for a third of our grade.

“Hey, Laine.” Topher is standing next to me, looking cautious. “Good luck tonight.”

I smile over at him. The teal makes his dark gray eyes stand out. “You too. I just hope we don’t have to sing ‘Java Jive’ for the encore.”

Topher opens his mouth to say something else, but Ms. Dunston hisses, “Places!” and all chattering ends as we quickly shift into position. I catch Topher’s smile and return his quick thumbs-up. This is it—our last song.

Applause washes over us as we stride onstage. Of course, Mom took an hour or so off from La Salle, and I look out into the audience, blinded by the footlights and flashes from hundreds of cameras, hoping to see her. As my eyes wander over the darkened auditorium, I glimpse someone standing by the side entrance, leaning against the wall with his arms crossed. My brain identifies Simeon Keller long before my eyes do. I suck in a huge breath.

The basses start the first notes to Ellington’s “It Don’t Mean a Thing,” and I’m caught off guard. I glance at Ms. Dunston, and she’s pointing at the altos. We come in, our “doo-wop, doo-wop, doo-wop” synchronized perfectly with the tenors, just like we’ve practiced. I snap my fingers with the rest of my section on cue, but my stomach is roiling. What’s he doing here? Was that really him?

It’s a busy song, full of quick changes and tandem movements, and I can’t afford to get lost. Finally, we reach our big finish, but when I glance that way again, nobody’s there. It’s crazy. He wouldn’t come back now, I know, and certainly not back to a school show. But still, there’s a deep disappointment that drags at me throughout our performance. Even the encore, “A Quiet Place”—my all-time favorite song—does nothing for my mood. I skip the after-show reception and opt to leave with Mom.

“You looked like you were having fun up there tonight,” my mother says. She turns down the street from the school and merges into the busy traffic. “If the food business doesn’t work out for you, maybe you can hire yourself out in Las Vegas.”

“Oh, nice.” I mock-scowl. “Like I haven’t had enough with the sequins and I need feathers.” I touch my fingertips to the rose Ms. Dunston got all of her seniors. I feel a little melancholy. Already the edges of the petals are curling.

“Sure you don’t want to wear this in the kitchen? All the line chefs will want to see it.”

I laugh and look down at my finery. “Yeah. I can hear them now. No, I’ll just change and be over in about an hour.”

“Why don’t you drop me at La Salle and drive back? It’s still a little drizzly for walking.”

“Mom, I need to walk after standing still in these stupid shoes all night. Don’t worry about it, okay? A little rain won’t melt me.”

My mother makes a noncommittal noise and smiles. Since we’ve been back, I’ve sensed that she’s been trying to keep her distance, trying not to order and organize me quite so much. It’s still a struggle for her, but she’s trying. In return, I’m trying not to mind so much when she does look at me and sees what I could be instead of what I am. Maybe it’s part of being a mother, maybe it’s a management skill she’s picked up from La Salle, but I am learning to live with it and with her.

At home, I slip out of the hated teal dress one last time and wonder gleefully which unlucky underclassman will inherit it from me. Pulling the pins out of my hair, I wind it into a simple bun on the nape of my neck, relieved to be looking more like myself. The front door closes, and I grab my sweatshirt and jog down the stairs, smothering my irritation.

“Mom, I said you didn’t have to wait….” My voice trails off as I realize the room is empty. “Mom?”

I come down the last few stairs, frowning. As I reach the door, I glance at the coffee table. I see my name on an envelope in a familiar scrawl, and it hits me. It was not my imagination.

I snatch open the door.

“Simeon!”