Like many rivers on the Olympic Peninsula, the Quinault has two branches in the mountains, and it drains a large part of the southwestern Olympics. The North Fork, flowing down from Low Divide, and the East Fork, which heads near Anderson Pass, come together in the foothills. The river then flows through a broad, level valley to Lake Quinault. Glacial action created this lake during the Ice Age, when an alpine glacier deposited rock debris across the valley, thus damming the river. The lake lies on the edge of the mountains, midway between the river’s source and the Pacific Ocean. Below the lake the Quinault River meanders across the Quinault Indian Reservation.

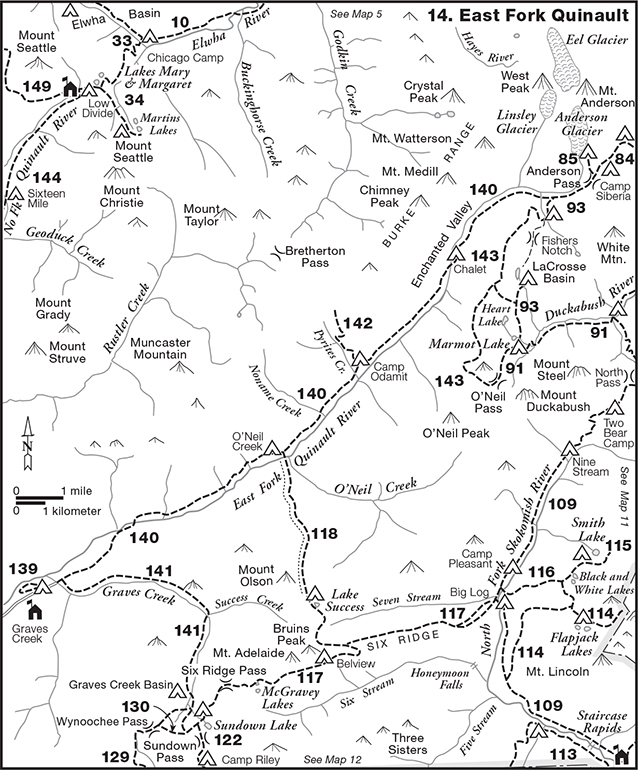

The East Fork Quinault, sustained by glaciers on Mount Anderson, sweeps in an almost straight line down a long, narrow valley bordered by timbered mountains. The deep upper part, walled in by precipitous slopes, is known as the Enchanted Valley. On the northwest, it is flanked by the Burke Range, so named in 1890 by the Press Expedition for Judge Thomas Burke of Seattle. The most important peaks in this range, which soar to almost 7000 ft/2134 m, are Crystal, Chimney, and Watterson. Muncaster Mountain, rising between the East Fork and Rustler Creek, marks the range’s western end. The major peaks southeast of the East Fork—LaCrosse, White, Duckabush, and Steel—exceed 6000 ft/1829 m in elevation.

Below Enchanted Valley the East Fork is bordered by high, forested ridges. The river is paralleled on the north by a ridge that extends from Muncaster Mountain to the forks of the river. South of the East Fork, the major tributaries—such as Graves Creek and O’Neil Creek—break the continuity of the ridges, beyond which lie the headwaters of the rivers that flow from the southern flanks of the Olympics.

Lake Quinault lies less than 200 feet above sea level, surrounded by low, forest-clad mountains which culminate in Colonel Bob (4492 ft/1369 m). The slopes north of the lake are in the national park, but the more impressive peaks and ridges to the south are in the national forest. The river flows into the lake’s northeastern end, where it has built a delta, then exits on the southwest side. Approximately 4 miles long by 2 miles wide, the lake covers 3729 acres and lies within the Quinault Indian Reservation.

The Quinault Valley is rain forest country, with an average annual precipitation of 140 inches on the lowlands and much more on the high peaks at the head of the valley. Because the temperatures are mild and the rainfall abundant, the trees on the river bottoms grow to enormous size, and the undergrowth is dense and luxuriant.

The East Fork Quinault was explored by Charles A. Gilman and Samuel C. Gilman in 1889 and by the O’Neil expedition in 1890.

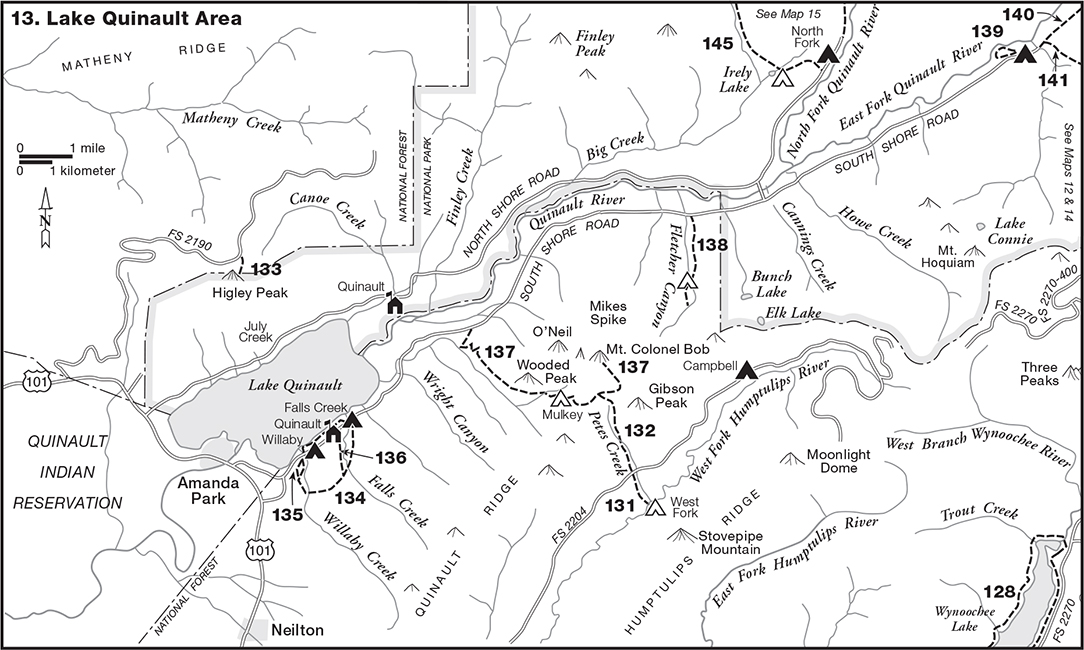

South Shore Road. The trails south of Lake Quinault and all those in the East Fork’s watershed are reached via the South Shore Road, which extends from the Olympic Highway, US 101, near the outlet of Lake Quinault, to Graves Creek on the East Fork. The road has two branches coming in from US 101 that form a Y at the west end. The north leg leaves the highway 0.1 mi/0.2 km south of the Quinault River crossing, 20.3 mi/32.7 km east of the Clearwater Road junction. The south leg leaves the highway 12.7 mi/20.4 km north of the Donkey Creek Road (FS Road 22) junction. (The distances to points on the South Shore Road are given here as if one were coming via the south leg; if approaching by way of the north leg, add 0.3 mi/0.5 km to the stated distance to any point.)

Along Lake Quinault the road goes by homes built among the spruce and fir trees and provides access to the Quinault Loop Trail and Willaby Creek Campground (1.5 mi/2.4 km). The road then enters Quinault (2.0 mi/3.2 km), where various facilities are located—including a lodge, general store, and ranger station.

Beyond Falls Creek Campground (2.4 mi/3.9 km), the road goes past farms and woodland homes—many well kept and prosperous looking, others not. The road continues through cutover land to Cottonwood Camp (11.3 mi/18.2 km), a primitive campground, then enters Olympic National Park (11.8 mi/19.0 km) at Bunch Creek, where the road closely parallels the river. Here one can look up the U-shaped valley and see snow-crowned peaks in the distance.

Within the park the stump ranches and fields are left behind as the road traverses beautiful rain forest. At Cannings Creek a bridge across the Quinault (12.8 mi/20.6 km) provides access to the North Shore Road. Beyond this point the route penetrates splendid stands of large Douglas-fir and spruce, as well as groves of gnarled bigleaf maples, garlanded with heavy growths of selaginella and mosses.

During the summer months, backpacking permits and trail information can be obtained at Graves Creek Ranger Station (18.5 mi/29.8 km). Graves Creek Campground (18.8 mi/30.3 km), located in a stand of fir and maples, is comparatively quiet, due to its isolated location; thus little traffic noise is heard. Nearby is the site of Graves Creek Inn, built in the 1920s and operated by the Olson family for many years. The road terminates at Graves Creek (19.1 mi/30.8 km), where the Enchanted Valley Trail begins.

Lake Quinault

The South Shore Road is subject to frequent closures, especially during the rainy winter and spring months. Before hiking extensively in this area, one should consult the National Park Service as to the conditions prevailing at the time.

FS Road 2190. This logging road leaves the Olympic Highway 2.1 mi/3.4 km west of the North Shore Road intersection and climbs through timbered country and clearcuts. One has a good view of Mount Olympus and Mount Tom from this road, but the scene is impaired by clearcuts on the intervening ridges.

The road climbs almost to the top of Higley Peak, then continues into the Canoe Creek drainage. The signed Higley Peak Trail is located at 9.6 mi/15.5 km.

Length 0.5 mi/0.8 km

Access FS Road 2190

USGS Map Matheny Ridge

Agency Olympic National Forest

The old Higley Peak Trail began near the national park boundary on the Haas Road, northwest of Amanda Park. The trail climbed the spur between Prairie Creek and Higley Creek to Higley Ridge, then followed the ridge to Higley Peak (3.0 mi/4.8 km), also on the national park boundary, north of the lake. However, since the construction of FS Road 2190, this old trail has virtually vanished. Mention is made of it here because of its historic importance.

The present trail (in the national forest) begins 9.6 mi/15.5 km from US 101 on FS Road 2190, at 2800 ft/853 m, where two small parking spots are located. The trail climbs through silver fir forest to the summit of Higley Peak (0.5 mi/0.8 km; 3025 ft/922 m).

This peak overlooks everything named Quinault—the lake, the valley, the ridge beyond—as well as Mount Colonel Bob and the forested ridges that lead to the snowy peaks of the Olympics. However, the view to the north is obscured by trees. The old lookout cabin was constructed in 1932 by the Forest Service and used during World War II as one of the government’s stations in the Aircraft Warning System. It was rebuilt on a wooden tower in 1964, then removed by helicopter in 1973. The building and tower are currently being used at Snohomish County Airport. A microwave reflector and tower that later occupied the space were removed in 2002.

Higley Peak was named for a pioneer family that settled on Lake Quinault. Alfred V. Higley, a Civil War veteran, and his son, Orte, arrived in October 1890, after following Lieutenant Joseph P. O’Neil’s pack train across the Olympics from Hood Canal via O’Neil Pass.

Length 4.0 mi/6.4 km

Access South Shore Road

USGS Map Lake Quinault East

Agency Olympic National Forest

One of three trails south of Lake Quinault, this route makes an irregular closed loop that has no beginning or ending point, and it lies less than 500 feet above sea level. The trail is described counterclockwise, beginning at the parking area on the South Shore Road 200 feet northeast of the Pacific Ranger District, Quinault office.

The trail follows Falls Creek, which until 2002 had its banks lined with protective gabions (wire baskets filled with stones). The gabions (and a dam) have since been replaced with erosion-control structures made of rock and logs. A bridge over the creek leads to the campground and picnic area east of the creek; walk-in campsites on the west side are just ahead.

Coming out to the lake, the trail edges the shore, going by houses, garages, and boat landings, and one can hear the traffic on the nearby road. The path then crosses in front of Quinault Lodge. During hot, dry weather sprinklers on the roof of this imposing establishment keep it wet as a safeguard against fire.

The jungle along the lakeshore consists of a rank growth of blackberry, salmonberry, skunk cabbage, thimbleberry, and hydrangea that has gone wild. The view is good across the lake to beautifully forested Higley Peak and the ridges to the north, but the mountainside to the northeast is scarred by a real estate development on private land within the national park boundaries. At one point the hiker can look up the Quinault Valley and see Mount Colonel Bob.

At Willaby Creek Campground (0.9 mi/1.4 km), the trail turns away from the lake, then crosses Willaby Creek and goes beneath the highway bridge that spans Willaby Gorge. The trail now enters the primeval forest, where the coolness is inviting on a hot day. This section along the gorge, with its luxuriant display of rain forest vegetation and big trees, is the most beautiful and imposing part of the route. The broad, smooth path, bordered by protective guardrails, climbs as it parallels the steep-sided canyon, which is lined with ferns (particularly sword and maidenhair), devil’s club, huckleberry, and salmonberry. The trees are impressive: giant firs, spruces, and cedars lift lofty crowns high above the jungle that borders the clear, rock-bottomed stream. The forest floor is covered with oxalis and several kinds of ferns—deer, sword, and maidenhair. Signs posted along the trail give information about the rain forest.

The path climbs to a junction with the Quinault Rain Forest Nature Trail (1.2 mi/1.9 km). The trail then leaves the big firs as it descends through stands of western hemlock (apparently growing on an old burn), crosses Willaby Creek, and returns to the virgin forest. Here it enters a swamp where western red cedars are abundant, including numerous dead snags. The trail now consists of puncheon, much of it an elevated boardwalk that curves around the trees and piles of logs.

Leaving the bog, the trail follows Falls Creek to a junction with the Lodge Trail (2.9 mi/4.7 km), crosses the creek, and goes through stands of western hemlock. After crossing Cascade Creek—a series of cascades and pools—the trail descends to the South Shore Road and the parking area at Falls Creek (4.0 mi/6.4 km).

Length 0.6 mi/1.0 km

Access South Shore Road

USGS Map Lake Quinault East

Agency Olympic National Forest

This trail begins at the parking area on the South Shore Road west of Willaby Creek, 1.5 mi/2.4 km from US 101. The trail ascends through the Big Tree Grove, one of the most impressive bits of old-growth Douglas-fir remaining in the Pacific Northwest. Although larger firs are found in the Olympics, this is an even-aged stand approximately five hundred years old. The stately trees are almost perfect in form, and they are all about the same size—6 to 10 feet in diameter and about 275 feet tall. The straight columns rise free of limbs for a hundred feet or more, and little pads of moss cling to the ribbed bark. Other species present include western hemlock, red cedar, and Sitka spruce. Oxalis and ferns carpet the ground.

Benches have been placed along the trail at various points, where one can relax and look—and absorb the mystery of the rain forest. Although the trail is short, one should not hurry through but take time to savor the magnificence. This is easy to do because the forest is quick to assert its primeval mood upon the visitor. One is both glad and sad—glad that this splendid remnant has been preserved; sad to realize that millions of acres of forest like this have been destroyed by fires and logging since the white man came to the Pacific Northwest. The Forest Service estimates that the timber growing here upon a single acre (approximately the size of a football field) would provide enough lumber to build forty average-size houses. However, the recreational and esthetic value of the trees is considered to be far greater than their value as lumber; consequently, they have been preserved for the enjoyment of present and future generations.

Because Douglas-fir requires mineral soil and sunlight to grow, it does not perpetuate itself in the shade. Therefore, an opening must have been made here about the time that Columbus set sail for the New World. The open area may have resulted from violent winds or perhaps from a fire such as occurs in the rain forest every hundred years or so during spells of unusually hot, dry weather.

Near the grove’s eastern edge, adjacent to Willaby Creek, the trail ends in a junction with the Quinault Loop Trail (0.6 mi/1.0 km). Hikers can return to the parking lot by retracing their footsteps or by following the loop trail along Willaby Gorge to the road just east of the parking area.

Length 0.6 mi/1.0 km

Access South Shore Road

USGS Map Lake Quinault East

Agency Olympic National Forest

Used chiefly by tourists staying at Quinault Lodge, this trail extends southward and intersects with the Quinault Loop Trail, thus making possible a couple of loop hikes.

The graveled trail begins directly across the road from the lodge (220 ft/67 m) and climbs through a dense stand of small hemlock, where the undergrowth consists chiefly of red huckleberry and vine maple. The trail soon levels and changes to a dirt path about a yard wide—much broader than the typical backcountry trail. The trees are now larger; the route is bordered by excellent examples of Sitka spruce and western red cedar, with a few large Douglas-firs present. The forest floor is covered with many moss-covered logs and stumps and by a rich undergrowth of oxalis, ferns, and huckleberry.

The path traverses above Falls Creek, then ends in a junction with the Quinault Loop Trail (0.6 mi/1.0 km). The hiker who wishes to return to the lodge from this point has a choice of three routes: going back over the route just walked or traveling east or west on the Quinault Loop Trail. The distance via the Lodge Trail is less than going in either direction on the loop trail.

Length 7.2 mi/11.6 km

Access South Shore Road

USGS Maps Lake Quinault East; Colonel Bob

Agency Olympic National Forest

Colonel Bob is the highest of four peaks clustered together about 5 miles east of Lake Quinault and south of the Quinault River. The name McCallas Peak—for John McCalla, one of the first settlers on the lake—was given in 1890 to one or perhaps all four peaks (considered as one), consisting of Mount O’Neil, Colonel Bob, Gibson Peak, and Wooded Peak. Colonel Bob was named later for the noted nineteenth-century agnostic Robert Ingersoll; Mount O’Neil, so named in 1932 for Lieutenant Joseph P. O’Neil, leader of the O’Neil Expeditions, was formerly called Baldy.

This collection of peaks forms part of the south slope of the Quinault Valley, between the lake and the national park. The beautifully timbered mountains rise 4000 ft/1219 m above the bottomlands along the river. This area is now protected because it is within the Colonel Bob Wilderness, which was established in 1984.

The trailhead (230 ft/70 m), located on the South Shore Road, 6.0 mi/9.7 km from US 101. The terrain is steep, and the trail begins to climb at once through conifer forests, where the undergrowth is mostly sword and maidenhair ferns. Mixed with the slender hemlocks are huge firs and cedars. Higher up the slope, some of the large trees have been scarred by fire. The big trees are survivors of a former stand; the younger hemlocks have grown up since the fire.

The trail climbs steadily, paralleling Ziegler Creek, which can be heard below, to the right. As the path switchbacks up the mountain, the Douglas-fir gradually disappears, replaced by silver fir. Big rocks covered with mosses and ferns lie scattered through the forest.

Mulkey Shelter (4.0 mi/6.4 km; 2160 ft/658 m) is located in a marshy, jungled area infested with mosquitoes; therefore, one would be better advised to camp farther on at Moonshine Flats. The shelter was constructed by the Forest Service in 1930 to replace a cabin built about 1910 by Mart H. and Purl Mulkey. The brothers had a trapline that extended from the Colonel Bob area to Bunch Lake, where they had another cabin.

Making about a dozen switchbacks, the trail climbs sharply to Quinault Ridge (3200 ft/975 m). Here the terrain falls away sharply on both sides, and the forest is mostly western hemlock and silver fir. Now comes a disconcerting feature—the trail zigzags down, losing considerable elevation, before traversing beneath a rock cliff, where it crosses avalanche tracks.

Beyond the junction with the Upper Petes Creek Trail (5.5 mi/8.9 km; 3300 ft/1006 m), the route is devious, and unless one knows the way it is difficult to follow when covered with snow. The trail emerges from the deep forest and enters more or less open country. A cliff rises to the left, and ahead one can see a huge talus cone or slide on Gibson Peak. The trail is now rocky, not smooth like it was in the forest, and it crosses a little basin, where big boulders lie strewn helter-skelter. The tall grasses wave in the wind, accompanied by its murmur in the trees on the ridge. Wildflowers bloom profusely, mingled with smooth-slabbed rock outcrops. Here one will note daisies, lupine, thistles, Columbia lilies, arnica, and pearly everlasting.

Beyond this point the trail might well be called Salmonberry Lane. During the next half mile or so the path is bordered by a rank growth of the bushes. When the sweet, delicious berries ripen—usually around mid-August at this altitude—they are abundant, and the hiker is apt to linger and feast on the fruit.

Leaving the switchbacks and salmonberries, the footpath climbs to a gap (3700 ft/1128 m) that looks out over Fletcher Canyon to the peaks beyond the Quinault. The trail now veers to the left and descends to Moonshine Flats (6.3 mi/10.1 km; 3500 ft/1067 m). This subalpine basin lies between Colonel Bob and Gibson Peak, at the head of the canyon. Large boulders are scattered about, intermingled with beargrass, heather, and huckleberry. Several campsites are located beside Fletcher Creek, which flows over a bed of living rock. The vegetation is typical of the Subalpine Zone; the trees are chiefly mountain hemlock and Alaska cedar.

Forks of the Quinault

Beyond the camp, the trail climbs steeply as it traverses beneath dark basalt cliffs and switchbacks up to the ridge, where the wind often howls in the hemlocks. Here one can look both north and south. The trail angles back east, beneath Colonel Bob, to a saddle above a rocky basin, beyond which rises a three-humped mountain. The last 100 feet lead up a rock face, via steps hacked in the rock, to the summit of Colonel Bob (7.2 mi/11.6 km; 4492 ft/1369 m).

The Forest Service built a fire lookout cabin on the top of this peak in 1932, but it was removed in 1967. Here one has an outstanding, unobstructed vista of the Quinault country—the lake, river, valley, timbered foothills, Pacific Ocean and snowy peaks to the north and east. Mount Olympus is visible on the skyline. The view to the south encompasses ridge after ridge, heavily forested but scarred by numerous clearcuts.

The summit is a pleasant place to spend some time on a warm, sunny day. The squawking of ravens in the forest below is the only sound heard above the whisper of the wind, and one feels far removed from the frenetic rush of civilization.

The impressive spire (ca. 4175 ft/1273 m) rising midway along the ridge between Colonel Bob and Baldy, or Mount O’Neil, is known as Mikes Spike. George A. Bauer and the late Mike Lonac spotted the pinnacle in 1974, and Lonac later made the first ascent. Climbers can reach it by leaving the trail near the base of the final peak and traveling cross-country about 200 yards.

Length 2.3 mi/3.7 km

Access South Shore Road

USGS Map Bunch Lake

Agency Olympic National Forest

This interesting but little-known trail begins on the South Shore Road 11.3 mi/18.2 km from US 101, at 400 ft/122 m above sea level. Near its beginning the trail goes by a big rock covered with mosses and ferns, then crosses a little stream, where a tiny pool collects drinking water. Ahead and to the right one can see an area where the wind has knocked down many trees. Because sunlight easily penetrates the thin forest canopy, red huckleberries grow profusely in the devastated area.

The trail avoids the windfall by switchbacking up to the left. Here it enters the dark realm of fir—dense stands of tall, slim evergreens. The forest floor is covered with ferns and mosses, and large boulders are scattered about. Although the grade eases where the trail crosses a rock slide, the ascent is unrelenting. The path is both smooth and rough, but generally the former, and as the trail traverses the mountainside the forest gradually changes to western hemlock and silver fir.

At 1.0 mi/1.6 km, the route climbs steeply through huge, moss-covered boulders. After going by a wall clad with mosses and ferns, the trail slides to the right—to use Forest Service slang—and descends to Fletcher Creek. The stream is bordered by currant and salmonberry bushes, and one can see a waterfall ahead.

A large foot log spans the creek, and the trail crosses to a campsite in Fletcher Bowl, a comparatively level area (1.9 mi/3.1 km; 1450 ft/442 m). Beyond the camp, the trail meanders through a heavy growth of salmonberry, where one cannot see the footpath, merely a “way” through the jungle; then, leaving the flat, the path leads uphill through hemlock forest. The trail is poor, dim in places, often scarcely discernible, but the way is marked with colored ribbons.

After topping a rise, the trail traverses above the canyon, then descends to the bottom, where it ends among the boulders in the rocky creek bed (2.3 mi/3.7 km; 1500 ft/457 m). During late summer the creek flows underground at this point. Slide alder and vine maple are abundant; avalanche debris is scattered everywhere.

One can, if he is foolish enough, travel cross-country from here to the Colonel Bob Trail, striking that route just below Moonshine Flats (4.5 mi/7.2 km), but it is rough going and not recommended. The hiker headed for Moonshine Flats would be better advised to take the Colonel Bob Trail.

Length 1.0 mi/1.6 km

Access South Shore Road

USGS Map Mount Hoquiam

Agency Olympic National Park

Used mostly by casual walkers, this trail makes a circle adjacent to Graves Creek Campground. One should hike the trail counterclockwise, thus saving the best part for last. The trail is so described here.

The trail begins and ends near the river, at the campground’s west end (570 ft/174 m). After traversing a lovely stand of bigleaf maple garlanded with mosses and ferns, the path descends to a flat by the river and crosses an old gravel bar. This former channel of the river is still largely devoid of vegetation. The trail then comes out onto a grassy bench above the Quinault. Although many large, old firs stand on the far side of the river, the forest along the trail is large second-growth fir and spruce on land that, in geological terms, was recently riverbed.

After a bit, the trail veers away from the river and crosses flats covered with typical rain forest, including a fairyland of impressive bigleaf maples. The trail then meanders through firs up to 4 feet in diameter, returning to the starting point (1.0 mi/1.6 km).

Length 18.9 mi/30.4 km

Access South Shore Road; West Fork Dosewallips Trail

USGS Maps Mount Hoquiam; Mount Olson; Chimney Peak; Mount Steel

Agency Olympic National Park

This major route, one of the most popular trails in the Olympics, apparently attracts every serious hiker at one time or another. People hear about it from other hikers, or they read something somewhere, so they have to go see for themselves. Few come back disappointed.

The trail begins where the South Shore Road ends at Graves Creek (600 ft/183 m). The road formerly extended 2.4 mi/3.9 km farther up the valley, but the section beyond Graves Creek is now part of the trail. The route ends at Anderson Pass, on the southern flanks of Mount Anderson.

Beyond the old bridge over Graves Creek—now used only by foot traffic—the trail climbs to a junction with the Graves Creek Trail (0.1 mi/0.2 km). As it follows the old roadbed, the route goes through a magnificent forest of giant firs and cedars. Many trees are 6 to 8 feet in diameter and more than 250 feet tall. The undergrowth consists largely of huckleberry, vine maple, and devil’s club. On the forest floor, queencup beadlilies and bunchberry dogwood add festive touches of color, scattered as they are among the sword and deer ferns.

A picnic table (2.4 mi/3.9 km; 1178 ft/359 m) marks the end of the abandoned road and the point where the forest changes to western hemlock and silver fir. The path descends steeply to the East Fork Quinault, and one can hear the river in the distance.

At the Pony Bridge (3.0 mi/4.8 km; 903 ft/275 m) the river plunges through a narrow gorge walled by layers of slate and sandstone inclined almost vertically, the rock sheathed with maidenhair ferns. A camp is located just beyond the bridge—the first of more than half a dozen riverside camps found along the trail in the next 2 miles.

The trail parallels the East Fork and is characterized by numerous ups and downs as it traverses moraine, terraces, and deposits of river gravel, descending to the stream’s banks at the various camps. The forest now includes Sitka spruce, with a few big firs scattered among the alders and maples on the bottomlands. The broad-leaved trees are festooned with mosses, lichens, and liverworts. As it follows the meandering river, the trail winds through shadowy forest aisles.

The valley is pleasant, cooled by gentle breezes that come down from the snowfields at the river’s head. Most of the time the Quinault rushes by noisily, but where it is deep and quiet the sound is soothing and peaceful. Except for the show of white water when it is broken by rapids, the river is pale green, especially in the morning; but it becomes turbulent on warm afternoons when the snow melts rapidly.

O’Neil Creek Camp (7.0 mi/11.3 km; 1179 ft/359 m), reached by a spur path, lies between the trail and river, opposite the point where O’Neil Creek flows into the East Fork. At this camp one can ford the Quinault to reach the abandoned Mount Olson Trail on the opposite side.

Beyond O’Neil Creek, the trail crosses numerous streams, several of them bordered by alluvial fans. A good campsite is located at Noname Creek (8.5 mi/13.7 km) and another at Pyrites Creek (10.0 mi/16.1 km; 1450 ft/442 m), where the old Pyrites Creek Trail begins. This site was named Camp Odamit by the party Lieutenant Joseph O’Neil sent to Mount Olympus in 1890. As it meanders up the valley, the trail crosses a number of small tributaries, but only one, Lamata Creek, has been named.

The path enters Enchanted Valley at the point where the river is spanned by a footbridge (12.6 mi/20.3 km; 1920 ft/585 m). Fred W. Cleator, a Forest Service employee, named Enchanted Valley in the late 1920s, when it was part of the Mount Olympus National Monument.

As the name implies, the valley is a lovely place, its charm enhanced by its isolation from highways and vehicular traffic. Perhaps it could best be described as somewhat resembling a miniature Yosemite. A glacier which filled the valley during the Ice Age deposited a moraine at the lower end. When the glacier retreated, the moraine dammed the river, thus creating a lake. However, both the glacier and the lake have been gone for thousands of years. On the valley floor the Quinault splits into a multitude of braided channels. The flats along the river, covered with lush grasses and alder groves, are bordered on the northwest by a cliff, 4000 ft/1219 m high, the sidewall of the Burke Range, which isolates the valley from the streams that flow to the Elwha River. The ridge from O’Neil Pass to Anderson Pass forms the less abrupt southeastern side, which is heavily forested. The valley floor is more or less open and free of evergreen forest—possibly due to heavy accumulation of snow during the winter.

When the snowdrifts on the Burke Range melt in early summer, hundreds of cascades plunge down the cliffs. They are responsible for another name, Valley of a Thousand Waterfalls. By late summer, when the snow is gone, most of them have disappeared, but a number remain. During the winter and spring, avalanches sweep down these cliffs, and the snow piles up, creating snow cones at the bottom. Accordingly, tiny ice fields cling to the mountainside near its base.

Enchanted Valley Chalet (13.3 mi/21.4 km; 2000 ft/610 m), a three-story log structure built in 1930, now serves as a ranger station only and is not available for visitor use except during an emergency. (The National Park Service does not consider poor weather to be an emergency.) The chalet stands near the western end of a flat, grassy meadow. The view from here includes the Linsley Glacier on Mount Anderson, as well as the valley’s northwestern wall, with its waterfalls and pockets of ice. Fingers and islands of Alaska cedar break up the continuity of the barren cliffs, which are composed of slate and sandstone mixed with greenstone (a metamorphosed basalt).

At the head of Enchanted Valley, about 2 miles beyond the Chalet, the trail begins its ascent to Anderson Pass. The largest known western hemlock stands near the trail, its status proclaimed by a sign. The tree is almost 9 feet in diameter, and other hemlocks in the vicinity are nearly as large. The river, now constricted between steep, timbered slopes, cascades noisily over boulders and rocks. At this point Anderson Creek tumbles down from Linsley Glacier on Mount Anderson, adding its volume to the river.

As it climbs out of the valley, the trail makes an ascending traverse high above the roaring Quinault, going through stands of silver fir. The trail crosses White Creek just below a waterfall. This brawling stream flows down the north slope of White Mountain. Beyond the junction with the O’Neil Pass Trail (16.9 mi/27.2 km; 3200 ft/975 m), the trail switchbacks as it climbs steadily toward Anderson Pass. On warm days torrents of water plunge down the slopes of Mount Anderson, and on rare occasions the stillness may be broken by the crash of ice falling from Linsley Glacier. When the weather is hot, one should make the climb to the pass during the morning because the afternoon sun bears down upon this mountainside.

The view from Anderson Pass (18.9 mi/30.4 km; 4464 ft/1361 m) looks east across the valley of the West Fork of the Dosewallips, west down the Quinault. At the pass the route becomes the West Fork Dosewallips Trail, and the Anderson Glacier Trail ascends the lower slopes of Mount Anderson.

Length 8.6 mi/13.8 km

Access Enchanted Valley Trail; Six Ridge Trail

USGS Map Mount Hoquiam

Agency Olympic National Park

The Graves Creek Trail branches right from the Enchanted Valley Trail just beyond Graves Creek bridge, follows the stream to its headwaters, then traverses the Graves Creek–Six Stream Divide to Six Ridge Pass. Of botanical interest on this route is the fact that large trees persist to comparatively high altitude. Several vantage points along the trail afford splendid views of the Graves Creek gorge and early-season waterfalls on the opposite mountainside.

The trailhead (646 ft/197 km) is located in a setting of western red cedar. The path first climbs above Graves Creek—which can be heard but is not visible—onto a bench covered with stands of hemlock, cedar, and fir. Little streams are numerous, and the ground is blanketed with luxuriant undergrowth, such as oxalis, vanilla leaf, queencup beadlily, and ferns (sword, deer, and maidenhair). This is also elk country, and the animals’ tracks are everywhere. On occasion the lucky hiker may see a herd.

The trail gains elevation gradually, and the sound of the creek disappears. Then, after a bit, the trail descends, and Graves Creek, still hidden, can be heard again. In fact, this stream is just the reverse of what children are supposed to be like—it can be heard continuously but is almost never visible.

As it follows the creek’s course, the trail traverses high above the deep, curving canyon. The forest here is in a state of transition. Large firs are not numerous, and several big ones have fallen in recent years. When a trail crew cut out sections of two trees that were lying across the trail, the men recorded the number of growth rings. One tree was 563 years old; the other, 643 years.

Traversing high above Graves Creek, the trail rises and falls as it crosses several streams. Now, for the first time, one can glimpse the creek occasionally, the white water rushing furiously through a box canyon walled in by timbered mountainsides. The creek has a steep gradient, with many falls and cascades, hence the booming and thundering. The sound is intensified after heavy rains or when the snow melt in the high country is at its peak.

The trail climbs steadily, crossing avalanche tracks overgrown with maple, salmonberry, and slide alder, then descends to Graves Creek just below its confluence with Success Creek (3.5 mi/5.6 km; 1880 ft/573 m). The stream is not bridged, and the crossing is difficult in late spring and early summer when the water is deep and swift; but one can cross easily in late summer and fall.

Beyond the ford the trail switchbacks up through hemlock and silver fir, makes a long traverse to a large creek, then descends to a camp on Graves Creek (5.3 mi/8.5 km; 2520 ft/768 m). The camp is located at the lower end of Graves Creek Basin, which consists of a series of openings in the forest where the stream is no longer in a canyon.

At this point the trail again crosses the creek, which must be waded if one cannot find a suitable log to serve as a footbridge. However, the stream is much smaller here. After crossing two avalanche tracks, the trail intersects the Wynoochee Trail (6.0 mi/9.7 km; 2700 ft/823 m) in a stand of western hemlock and silver fir, then switchbacks up the mountain, following the course of a stream.

Temporarily marked by ribbon tied to bushes beside a large cut log (6.6 mi/10.6 km; 3400 ft/1036 m), a faint track leads uphill on the right side of the trail. This is the eastern terminus of Sundown Lake Way Trail.

As it climbs higher, the trail breaks out into little bits of meadow on the steep sidehill, then bigger, more extensive openings. The trees are now mostly hemlock (both western and mountain) and subalpine fir. Here several rock-bottomed streams flow down the mountainside, where big boulders, covered with lichen and moss, lie scattered about. The view to the north down Graves Creek includes snow-clad peaks beyond the forested ridge in the foreground.

The junction with the Upper South Fork Skokomish Trail (7.2 mi/11.6 km; 3820 ft/1164 m) is located in a big meadow. This is lovely subalpine country—beautiful meadows framed by mountain hemlocks, with masses of showy white beargrass plumes and an abundance of dwarf huckleberries. The latter tempt one to linger even when time is pressing.

Beyond the meadow’s far edge, the trail contours a steep slope through stands of large, pistol-butted mountain hemlocks. When the trees were young, the snow pushed against the trunks, causing them to lean; then they grew upright again, creating the pistol butt effect at the base of the trees.

A shelter once stood near the outlet of Sundown Lake (7.5 mi/12.1 km; 3900 ft/1189 m). No more. This oval-shaped tarn lies at the bottom of a steep-sided glacial cirque. The lake is bordered by narrow fringes of meadowland and brush, with forest above, and is oriented so that the outlet—and the only view from the cirque—is toward the setting sun in summer; hence the name. The lake is popular with fishermen because it is stocked with rainbow trout. A large meadow, where a few patches of snow linger throughout the summer, extends from the head of the lake to the ridge crest.

Beyond Sundown Lake the trail climbs through stands of big mountain hemlock as it traverses the cool, shaded north slope beneath low cliffs, then crosses broad meadows made attractive by groves of subalpine trees, rough sandstone boulders, and wildflowers, including the white lupine. The common blue lupine, beargrass, and false hellebore are abundant. Huckleberries also grow profusely here. The sweeping view is dominated by Mount Olympus on the horizon. The trail then climbs sharply, switchbacking up steep, forested slopes that alternate with meadowland as the route climbs to Six Ridge Pass (8.6 mi/13.8 km; 4650 ft/1417 m), where the path becomes the Six Ridge Trail. At this gap in the narrow divide, the gentle summer breezes murmur faintly in the hemlocks. During other seasons, however, the trees struggle for existence, pitting themselves against the fierce winds and the cold.

The view from the pass is splendid. Mount Rainier stands to the southeast, appearing ethereal and unreal. The Sawtooth Range, less than 10 miles distant, is dominated by Mount Lincoln and Mount Cruiser. One looks down the valley of Six Stream, which is bordered on the north by Six Ridge and on the south by the Three Sisters. One of the McGravey Lakes glimmers in the forest below. Beyond the heavily-timbered ridges rise snow-clad peaks—among them Mount Henderson, Mount Duckabush, and Mount Olson.

Abandoned trail, no longer maintained

Length 3.0 mi/4.8 km

Access Enchanted Valley Trail

USGS Map Chimney Peak

Agency Olympic National Park

An old trail that is virtually nonexistent today, this route should be reopened by the National Park Service to give backpackers access to the Burke Range, particularly the beautiful high country of Muncaster Basin. The trail is on the route taken by the party Lieutenant Joseph P. O’Neil sent to Mount Olympus in 1890.

The trail began—one hesitates to say begins—at Camp Odamit (1450 ft/442 m) on the East Fork Quinault River and followed Pyrites Creek about two-thirds of the way to the ridge between the East Fork Quinault and Godkin Creek. Although a few fragments can still be found, it is easier to forget the trail and just go straight up the mountain, traveling parallel to the creek, but following the bits and pieces of the path when they are encountered. The trail kept close to the creek the first half of the ascent, then angled away from the stream, ending not far above The Crow’s Foot, where three branches of Pyrites Creek come together (3.0 mi/4.8 km; 3800 ft/1158 m).

Length 7.4 mi/11.9 km

Access Enchanted Valley Trail; Duckabush Trail

USGS Maps Mount Hoquiam; Mount Olson; Chimney Peak; Mount Steel

Agency Olympic National Park

This trail begins at a junction (3200 ft/975 m) with the Enchanted Valley Trail near White Creek, 2.0 mi/3.2 km below Anderson Pass. The trail goes southwest to O’Neil Pass, at the head of the Duckabush River. This gap was used in 1890 by the O’Neil Expedition’s mule train when it crossed the Grand Divide.

At first the trail climbs through the forest to an attractive camp at the lower end of beautiful White Creek Meadow (0.6 mi/1.0 km; 3750 ft/1143 m), which is characterized during the summer by vivid displays of wildflowers, particularly lupine. Here the hiker has a good view of Mount Anderson and Linsley Glacier. This is just below Bull Elk Basin, where the expedition killed an elk. The trail meanders over the meadow east of White Creek, then crosses the stream. (The experienced mountaineer can leave the trail here and travel cross-country to Lake LaCrosse.)

The trail then goes back into the forest and traverses below the ridge that borders LaCrosse Basin on the west. Because the slope is steep, this is an avalanche area, and after winters of heavy snowfall the route may be blocked by deep drifts until late summer. Most of the distance, however, the trail goes through scenic stands of conifers that alternate with snowslide tracks. This traverse overlooks Enchanted Valley, and when the skies are clear Lake Quinault and the Pacific Ocean glimmer in the distance. Mount Anderson and Linsley Glacier still dominate the northern skyline, but now one can look directly across Enchanted Valley to the Burke Range, topped by Chimney Peak (6911 ft/2106 m). The cliffs that form the northwest wall of the valley, crowned by snow cornices and streaked by cascades and waterfalls, stand in full view, rising almost directly from the braided channel of the Quinault.

Beyond a junction with the Heart Lake Way Trail (3.8 mi/6.1 km; 4300 ft/1311 m), the trail comes out to a big basin (5.7 mi/9.2 km; 4700 ft/1433 m) on the northwest slope of Overlook Peak. This basin is often covered with snow. The path then rounds the peak’s western spur, where it goes through dense growths of young conifers (mostly mountain hemlock), among which stand many large, dead snags. The thick undergrowth consists of heather, mountain ash, and huckleberry. The presence of the latter probably explains why O’Neil’s men saw several bears on this mountain.

The trail almost encircles Overlook Peak as it contours above Upper O’Neil Creek Basin. Below the trail an old path—probably a remnant of O’Neil’s mule trail—leads down into this beautiful area, where a small stream flows through the meadow. The expedition had its Camp Number Fifteen here. One should watch for elk; their tracks are almost always visible in the mud and snow. This basin is often covered with snowdrifts until midsummer, but when they disappear the wildflowers bloom profusely. Large marmots, mottled black and brown, whistle warnings when hikers approach. The narrow ridge to the south is covered with mountain hemlocks, and an elk path leads across it to O’Neil Creek Basin.

O’Neil Pass (7.4 mi/11.9 km; 4950 ft/1509 m) is merely a tree-covered notch in the ridge between Mount Duckabush (6233 ft/1900 m) and Overlook Peak (5700 ft/1737 m). The view is good when the peaks are not hidden by clouds: to the north are Mount Anderson, Linsley Glacier, and White Mountain; the bulk of Mount Duckabush is close at hand to the south. The eastern scene includes the upper Duckabush Valley and Mount Elklick; the western one, the Quinault Valley and O’Neil Peak. Beyond the pass the trail becomes the Duckabush Trail.

The hiker with a flexible schedule can make the trek over to O’Neil Creek Basin, one of the loveliest places in the Olympics, which may be reached by following the elk trail from Upper O’Neil Creek Basin. Lake Ben and two smaller, unnamed tarns are located in the center, surrounded by subalpine meadows where the hiker can roam at will. Good examples of quartz can be observed in the rock slides, and the outcrops reveal evidence of glacial polish. The view down O’Neil Creek is striking, and several until recently unclimbed peaks rise directly south of the basin. The view from the divide east of the lakes makes the steep scramble up worthwhile because snow-clad peaks are visible in all directions, and one can look directly down to the North Fork Skokomish. Camp Nine Stream, little more than a mile distant, lies 3000 feet below the observer.