APPENDIX 1

THE LINEAGE OF MYTH

The creation myths of the Middle East and Egypt are far older than their written forms would suggest. According to Budge,1 the earliest Egyptian myths in the Book of Coming Forth by Day originate from stories that must have been told orally and illustrated before the Fifth Dynasty of Egypt, in the mid-third millennium BCE. For example, the Egyptian myth of Osiris was apparently never fully written down in any language until it was transcribed into Greek by Plutarch, who visited Egypt from Greece in the first century CE. Throughout the earlier period, before 3500 BCE to 1000 BCE, the Egyptians’ popular understanding of the stories must have depended largely on the illustrations and the rituals that accompanied their recital in public celebrations.

The flowering of the Sumerian culture took place around 3,000 BCE.2 Sumerian myths followed an evolution similar to the Egyptian, starting as oral stories long before they were written in cuneiform in 2700 BCE. Frankfort points out that the earliest cylinder seals depicted scenes from daily life.3 Only later, perhaps in the early years of the second millennium, were mythic themes extensively developed. The myths are well represented on the cylinder seals in common use of the period.

In choosing and presenting myth we have taken pains to find the very earliest forms. To approach the very earliest meanings of the myths and to understand these ancient societies requires a breadth of view that encompasses their rituals, texts, architecture, and other cultural elements. In this appendix we attempt to provide the reader with insights into the lineage of the myths we use in the book built on all of these tools.

The Egyptian Lineage

Egyptian mythology is relatively uniform and recognizable over long periods in the texts and figures written on walls of pyramids, temples, and tombs, and even inscribed on mummy wrappings. The original hieroglyphic texts tend to be well known and repeated faithfully from place to place, but that is not to say that there were no changes over time.

The writing in Old Egyptian hieroglyphs used to record the Pyramid Texts in the pyramids in the Fifth and Sixth Dynasties, circa 2300 BCE, has an especial clarity and beauty. Modern scholars have discerned their meaning with the help of fragments of the extensive ceremonial figures that lined the once-enclosed pathway leading from the Valley Temple on the banks of the Nile up to the pyramid.4

In the subsequent Sixth Dynasty, pharaohs were commemorated in the pyramids of Saqqara with written texts, which are extensively enhanced in nearby temple chambers with stories depicted in the beautifully carved or painted images.

The much later Twelfth Dynasty structures, circa 2000 BCE, housed in the Karnak Temple Complex, used a similar technique of both texts and images. This continued into the two main Eighteenth Dynasty temples, circa 1500 BCE, one at Karnak and one at Luxor. Other important sources of written and pictorial materials from this time period are carved and painted in passageways and chambers of the tombs of the Eighteenth to Twenty-second Dynasty pharaohs in the Valley of the Kings, across the river from Luxor proper. Interpretation of Egyptian imagery plays an essential role in our modern understanding of the often terse or enigmatic written texts.

Translations of the Egyptian Book of Coming Forth by Day have been widely known since they were first published in both hieroglyphic form and English by Budge in the last years of the nineteenth century.5 Budge misnamed it the Book of the Dead, following Lepsius, who in 1867 used the German term Todtenbuchs for texts discovered before the first Pyramid Texts were found and translated. Faulkner’s translations used the Book of Going Forth by Day as well as the Pyramid Texts.6 Faulkner’s later translations have been of great value, even though they do not include the images that are an informative part of Budge’s translations. Even more recently, Ashby uses the more proper name the Book of Coming Forth by Day, which is the title we use here.7

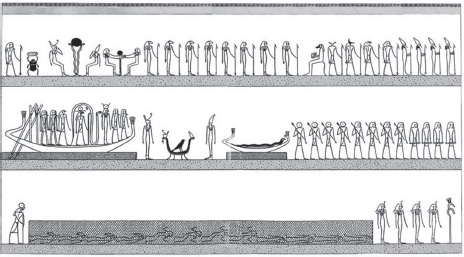

Budge points out that the very earliest Egyptian “sacred” writing refers to early versions of these texts, although for his own publications he uses revised and amplified texts written on papyri or on mummy wrappings from the much more recent New Kingdom, together with the illustrations that accompanied them. Also particularly useful are the Book of Gates, whose texts and scenes are inscribed on the walls of the tomb of Ramses I (Nineteenth Dynasty) and Ramses VI (Twentieth Dynasty), and the Book of What Is in the Duat, whose texts and scenes are inscribed in full on the walls of the tomb of Tuthmosis III (Eighteenth Dynasty).8 One panel is shown in figure A1.1. By the New Kingdom of the Eighteenth Dynasty, the Book of Coming Forth by Day included extensive commentaries added by the priesthood, marked by phrases such as “What then is this?” or “As others say.” In all cases, the translations are made clearer by reference to the many inscriptions and symbolic figurations that accompany almost all the texts. As is persuasively demonstrated by Naydler, it would often be difficult, if not impossible, to understand the textual symbolism without the accompanying images.9

The main differences among the modern-day translations of the Egyptian texts, and they are quite substantial, are a result of varying interpretations by modern translators. There is a distinct difference in tone between the translations of Budge and much of the more recent material. Recent linguists and translators hold Budge’s versions to be woefully outdated;10 however, in our eyes, Faulkner’s translations of the Pyramid Texts—which do not include illustrations—are sometimes completely unintelligible.11 More recently, a version published and illustrated by Naydler demonstrates the advantages of an author having an appreciation of the environment in which Egyptian beliefs developed.12 J. P. Allen’s book The Ancient Egyptian Pyramid Texts updates the full collection of texts from ten Old Kingdom pyramids.13 We use Allen as it is the most comprehensive collection, and he provides a full concordance table for the use of anyone interested in referring to the other collections.

Figure A1.1. Tenth Hour of the Book of What Is in the Duat, from the tomb of Tuthmosis III. From West, Serpent in the Sky.

It is also essential to reference the major work of R. A. Schwaller de Lubicz, Le Temple de l’homme (The Temple of Man).14 Schwaller and his wife, Isha Schwaller de Lubicz, spent decades in Egypt exploring the Ancient Egyptian culture. In his book The Temple of Man he presents an exhaustive exposition of Egyptian mathematics, geometry, architecture, and art. In doing so he gains insights into the cultural and spiritual underpinnings of the ancient Egyptians. He shows how differently they approached life. From his work they are seen to view the world as an eternal, creative whole with a unifying life force.

The Sumerian Lineage

Similarly, for the Sumerian myths, we must draw on the translated texts as well as images. While we have access to a number of translated texts, many others remain untranslated. Unfortunately, in contrast to the historical record in Egypt, we have only limited and secondary information about Sumerian rituals. We draw on the available Sumerian, and subsequent Babylonian, materials to explore the nature of the information the Mesopotamian myths contain. In doing so, it is important to note that the wedge-shaped Sumerian cuneiform script is totally different from the alphabetic Semitic language in which the later Babylonian versions were written. Mitchell points out that “Sumerian is a non-Semitic language unrelated to any other that we know, and is as distant from Akkadian as Chinese is from English.”15

Johnson points out, in relation to the Mesopotamian myths, that the earlier Sumerian culture transitioned into a quite distinct later Babylonian culture through “development of the basic institutions of ‘civilization’ . . . the growth of cities; the specialization of labor; the hierarchy of rulers, intellectuals and priests; the development of written records, libraries, courts of justice, measurement, astronomy; a common calendar; and a rich literature more than a thousand years before the Bible or the Iliad. It was the function of myth and ritual to bind the rich farmland of the rural areas to the capital city, and to bind the city to the temple, the palace, and the deified ruler. The primary role of the New-Year festival was to harmonize the cycles of earth, rural and urban, with the cycles of heaven.”16 This highlights the importance of the myth to the society over a very long span, before 3000 BCE to 1600 BCE, in parallel with the Egyptian culture.

For the Sumerian myths, Dalley, working with only written texts, points out that the written forms in which we have the various versions of the Sumerian myths may be quite different, both in their outline and in their thematic emphasis.17 The subject matter included in a late rendering of a text may entirely leave out one of the more central themes of an earlier version. In her opinion, some differences may be explained by the fact that not all versions were intended to be read to audiences; some are in the form of aides-mémoire, or summaries. In these documents, parts of the myth might be sketched in outline, while clearly important events may be referred to elliptically if at all. These short versions were used to assist reciters, to prompt teachers, to recruit entertainers, and even to record particular presentations. In keeping with this view, she notes that some of the earliest Sumerian versions of a myth may give us a rather longer and more complete form than the later versions, which appear in various languages (largely without illustrations) in the libraries of the second millennium BCE. As authors, we have found the need to maintain flexibility in our approach to their study, not placing undue reliance on any one version. We attempt to keep our view of what is said in the various sources as open as possible, without sacrificing attention to trends and without missing the deliberate alterations that arose in the various societies where the myths appeared.

In Mesopotamia, we see the continuing interest that the ancients took in their legends through the many copies of the cuneiform text that have been found throughout the area. The story of Gilgamesh was copied and recopied over a period of nearly two thousand years, from the third-millennium BCE text fragments found in the remains of the very early Sumerian culture of ancient Mesopotamia to the most complete edition, an Akkadian Semitic version found at Nineveh from the seventh-century BCE library of Assurbanipal, last king of the Assyrian Empire, written on twelve cuneiform tablets.

Some of the Mesopotamian myths known to us as rather extensive epics, such as the Epic of Gilgamesh with its story of the Flood, may have begun as shorter stories dealing with specific topics. The original eleventh tablet of this myth contains what is called the Chaldean account of the Flood. Significant fragments of the story of the Flood have been found at second millennium sites of the Hittite Empire in Anatolia, written in Semitic Akkadian. A Canaanite version was excavated from sites at Sultantepe in southern Turkey, and a Palestinian version from Megiddo.

The many parallels between the Mesopotamian story of the Flood and the later Hebrew and Christian stories make it apparent that the Hebrews modeled their story on the earlier version. They may have adopted it from their Babylonian captors or from a source that the Babylonians also used, all of which descended from the writings of the Sumerians.

Whichever path provided the transmission of the story, the Flood presented in the Bible is accepted by many as being derived from the Epic of Gilgamesh, a work that was known in the third millennium BCE, more than two thousand years before the Old Testament was composed.

Many different shorter tales, especially among the noncosmogonic, may have been utilized as oral storytelling material as part of the evening entertainment for commercial caravans in their increasingly extensive expeditions through the Middle East. Dalley believes that some versions of Mesopotamian myths found in excavations bear evidence of “competition” literature.18 She uses this term to describe situations in which storytellers, who regularly joined caravans in journeys over the deserts and took part in long sea voyages, were invited to vie with one another for the interests of their captive audiences. Records must have been kept of the stories that were particularly valued.

Our attention has been drawn especially to Mitchell’s version of the Gilgamesh legend; he reviewed seven previous translations in the process of producing it.19 Among the most important of the scholarly efforts for Mitchell is a modern English edition that includes both transliteration and cuneiform versions of the text written by George.20 Mitchell points out that the account accepted by scholars as the standard version of this epic was produced some five hundred years before the story discovered at Nineveh (dating to about 650 BCE), but much later than the Sumerian fragments that still exist and were used in chapters 2 and 3. This “ancestor” of the Gilgamesh epic is known as the Old Babylonian version and was written in Akkadian. It paraphrases some of the earlier Sumerian stories, which tell parts of the story of Gilgamesh and Enkidu, and includes Sumerian stories we have discussed that are not an integral part of the Gilgamesh epic.

Mitchell also points out that the Old Babylonian version is not really the basis for the story as we now have it because that version is very fragmentary. Instead, we have a translation produced by a scholar-priest named Sin-leqi-unninni, who elaborated on the Old Babylonian version some five hundred years after it was produced. His writing is now referred to by scholars as the standard version. Mitchell calls Sin-leqi-unninni a conservative editor, in that most of his translations, where it is possible to check the original, copy it line for line, with no changes in vocabulary or word order. However, with the unavoidable fragmentations, resulting in lost text, he ventures into expansions that show him to be an original poet. We are indebted to his intelligence and creativity, for they have assisted our understanding of the effect that such an important myth has had on our heritage.

Mitchell’s version is a refreshing new account representing a change in the general level of our understanding of ancient myths in recent years. To some his work will appear brash. We therefore need to recognize a new sense of value being shown in recent times. Advances in our understanding better reflect the ancient community of seekers who composed the Sumerian and Egyptian myths. No longer do we talk of ancient Egyptians as writing in “spells.”*12

The Potential for Shared Influences

Central to our study of myth is the book by Giorgio de Santillana and Hertha von Dechend titled Hamlet’s Mill.21 They provide a clear argument for an in-depth astronomical knowledge by ancient societies that has become a major source of information for subsequent cultures right up until today. For example, the sexagesimal system—which is the basis of the current system of degrees, minutes, and seconds of arc in the measurement of circles; the description of navigational geographic coordinates; and the measurement of time—is now recognized as a Sumerian invention for measuring angular changes in the position of astral bodies.

De Santillana and von Dechend demonstrate that the gods associated with the various constellations appear in the myths of Egypt and Mesopotamia. Further, these myths symbolically describe the relations among the stars, the planets, the sun, and the moon in their daily, monthly, annual, and precessional cycles in the skies. While we may never fully understand the extent to which these astronomic events shaped the ancient myths, there can be no doubt that they were a major factor.

Making Use of the Ancient in Modern Times

We have no particular expertise or objective basis for identifying the precise date of the first formulation of these myths. The subject is still a matter of debate among archaeologists and religionists whose special area of study is the geographic area of concern to us. Frankfort’s interpretation of the data, however, based on his wide experience, provides a reassuring guide for exploring this information. In particular, he points out that there is strong evidence for early (predynastic) exchanges between Egypt and Mesopotamia, but goes on to say, “comparison between [them] discloses, not only that writing, representational art, monumental architecture, and a new kind of political coherence were introduced in the two countries; it also reveals the striking fact that the purpose of their writing, the contents of their representations, the functions of their monumental buildings, and the structure of their new societies differed completely. What we observe is not merely the establishment of civilized life, but the emergence, concretely, of the distinctive ‘forms’ of Egyptian and Mesopotamian civilization.” 22

Ancient knowledge is not often well preserved through the long periods of disorder that follow the decline of a society. The ancient Sumerian culture was not even recognized as a distinct entity until the latter part of the nineteenth century CE. Kramer23 points out that it was not until the writings of Oppert in 1869 that scholars accepted the suspicion of Rawlinson24 that an entirely unknown non-Semitic language existed. Considerable progress has been made over the past half-century in finding resolutions for the sometimes vigorous debates over the translation and interpretation of the fragmentary evidence. Much of what has been found in official archaeological expeditions has now been carefully catalogued, and much of it is also published in forms that allow comparison by scholars. Initially these scholars were from the European nations that sponsored the excavations. However, interest developed in North America by the late nineteenth century and, in recent years, spread increasingly to various Asian centers with particular interest displayed by the nationals of the modern states in which the ancient ruins are still being excavated.

The spreading interest has encouraged excavators on many fronts, and inevitably, with time, substantial numbers of new fragments have appeared in the hands of commercial dealers, who have bought them from the original sellers or their representatives, and eventually sold them to the professionals. While some of these fragments have supplied vital information, the translators may be unable to establish the exact provenance of the materials themselves. The very proliferation of sources has added new work of examining and matching complementary fragments, or matching them with illustrations from various places. Ironically, parallel with this proliferation of source material has also come a proliferation of information, analyses, and discussions through the Internet, such as on the ETCSL site. Information of varying quality is made readily available there and is subject to varying degrees of synthesis and interpretation. This imposes a new requirement for discrimination on the part of readers that was not so evident in relation to more conventional, published scholarly efforts.

We can illustrate the kind of problem that can appear by drawing a parallel with the difficulty in confirming and releasing to the public the newly found and newly translated versions of books from the Old and New Testaments of the Bible. It was not until the mid-1900s that highly significant new sources for this venerated literature were found, both in Palestine and in Egypt. Preservation, translation, and interpretation of the new finds have occupied many experts, the results of whose efforts are only now, a half-century or more later, becoming widely known.

An important new perspective on what had initially been accepted as original, even inspired texts has resulted, generating controversy among both individuals and institutions. This is of particular interest for us because it demonstrates deep interest in spiritual matters in our Western society, despite the fact that it is largely secular in its outlook. It clearly speaks to us of the need for an open mind in attempting to arrive at a sense of original intentions.

The myths used here introduce questions and ideas about the origin and nature of the world, the arising of the gods, and the way they created and interacted with humans. It is of critical importance to current audiences that we see these creations and interactions as occurring within us—not in some external fairy-tale land. Through the myths, whole communities, perhaps at widely separated places throughout this ancient world, found a commonality of outlook that was important background for the arising of various religions. The stories themselves must have been repeated many times in different circumstances, and became widely known before they were written into the literature, which now affords us a chance to hear the tenor of the original aspirations. These stories incorporate important lessons about our inner self that were preserved for generations. This preservation may have been a stronger motive for the invention of writing than the more commonly acknowledged motive of keeping tally in early commerce.

We believe that recognition and communication of what is gradually being brought to light by these efforts results in new opportunities for making use of ancient knowledge. Recognition of the state of preparation of those who have supplied recent translations will be clear to all who are able to follow the lineage of the transcriptions over time. As an example, the recent publications by Naydler (Shamanic Wisdom of the Pyramid Texts) and Allen (The Ancient Egyptian Pyramid Texts) on the Pyramid Texts get a lot of meaning out of the order and location of the specific texts within the Pyramid complex. Without such knowledge of the flow of the corpus, much of our present understanding would be lost.

However, in addition to carefully adding new translations of ancient lore to our pool of knowledge, we must recognize that Western society tends to discount the importance of myth and equates technical superiority with superior intelligence. In our modern era, we can only speculate on the human motives and drives of the ancient past that led to these ancestral productions and ensured their preservation for our time. With the recovery of new fragments of these myths of old, however, Western society has begun to appreciate their magnitude and significance, not only to ancient audiences, but also to today’s seekers, who now lead widespread efforts to penetrate meanings first expressed in story form more than five thousand years ago.

To equate the ancient with the primitive, as suggested in Budge’s use of the derogatory word “spells” for the Pyramid Texts, creates an obstruction in an important pathway toward wisdom. It is important to see for oneself that the ancient understandings are far from primitive. In this book we have focused on creation myths, which we take to include the creation of the heavens and the earth, and of gods and humankind, together with certain necessary details for organizing rulership among the gods and over humankind in the gods’ attempts to serve their own needs. Myths that refer to the netherworld or tell mainly about the adventures of human or semidivine heroes, such as Gilgamesh, seem to deal with similar themes from a different perspective. In all we find common allusions to the arising of a greater being that can be equated to higher consciousness.