ONE

LIFE AND MEANING IN MYTH

Ancient myths are part of our cultural heritage. The Sumerian, Egyptian, and Hebrew myths that we investigate here have remained virtually unchanged in form over thousands of years and across wide areas of varied and changing societies. Although this is impressive, our purpose here is to determine their continued usefulness for a modern-day reader. In this chapter we explore some of the reasons for their longevity as a means of preparing the reader for the detailed discussion of the myths later in the book. Preparation is essential. We need to discover for ourselves a different approach to reading these ancient lessons.

Some of the myths that we address were originally recited to audiences by storytellers who, like the troubadours of medieval Europe, must have been gifted in their ability to convey the meaning of the tales. The prodigious feats of memory involved in recitation of the longer myths are so vast that they would surely daunt today’s professional actors. To judge by the narrative forms in which we now have these myths, such recitals required many long periods of listening. It even seems likely, considering their poetic form and rhythmic repetition, that recitation usually involved audience participation in the more familiar lines. But whatever the methodology, and despite their length and intricacy, these tales drew in audiences and held their interest. People gave birth, new audiences emerged, and the stories were told again and again in an ageless cycle, even through remarkable changes in the social structure of the societies in which the stories originated. Even now the continuing popularity of the stories is unquestionable.

An active connection between the audience and the myth is an essential element in the success of the story and in its transmission to succeeding generations. Although the active link that engages the listener in storytelling may be somewhat altered when a myth becomes a part of literature to be read alone, a receptive state is also necessary when reading with purpose. When we listen to myths, are we better prepared to employ them for our own benefit in the modern world?

Some of us remember how as children we were exposed to oral readings of dramatic fairy tales or fables. We may also recall how certain tales became favorites for which audiences clamored for repetition. The warmth of the interest and the deeply satisfying emotional exchanges that arise through oral storytelling, and the effects on both the storyteller and the audience, may be an important aspect of sustaining family relationships in the over-busy modern world of computers. Oral storytelling may have played a similar role among adults in an earlier phase of the development of Western society. Yet it is clear that the particular myths that have been preserved for our study and benefit must have special characteristics that illuminate a common understanding of human aspirations. These characteristics are inherent in the content of the stories and are not dependent on their method of transmission.

In our own time, the power in storytelling that must have been exerted in ages long past might be experienced in the overwhelming sensory impacts of modern movies or in the emotional sensitivities of theater productions. Perhaps this power might even be experienced through the unconscious repetition of themes in modern television programs. The continuing social importance of enactments of life experiences in the arts is most certainly attested by the large sums of money and time spent on theatrical productions of musicals and dramas. Amphitheaters, churches, music halls, opera houses, art galleries, and museums are major architectural features of past and present in the world’s great cities, and have become focal points for tourist sightseeing. These devices are gradually being replaced for modern generations by other means of communication such as television, and the Internet. But to a large extent these modern entertainments are primarily meant as distractions, not reminders of the subtle effects and unfamiliar sensations that are intentionally evoked in myth and storytelling.

This brings us to pose a serious question: Can we realistically experience in our social lives the almost miraculous, spellbinding qualities that might have been encountered in, for example, the public hearings of the ancient myth of Gilgamesh? Although it is known to have existed in written form for at least four thousand years, the average person encountered it only in public performance. And what about the details of the origin and evolution of our world found in the creation myth of the Babylonians, known as the Enuma Elish, and in the more recently discovered but antecedent Sumerian versions? Most of these initially attracted the attention of nineteenth- and twentieth-century researchers who were looking for stories antecedent to the Old Testament of the Bible. Their interest was confined to primarily solving particular problems of religious lineage as opposed to understanding the power of spoken myth.

And what is so special about the Egyptian myths of creation and development? They were apparently first told in the “obscure” times before the advent of hieroglyphic writing and seem never to have been written down at all in a coherent story form in Egyptian, despite the long and copious hieroglyphic records of the society. When written down, they were represented by hieroglyphs that the Egyptians called by the word “mdw·w-ntr,” or as we can now translate it, “neter’s words” or “the words of the gods.”1 The stories told in these myths were very well known over the whole of the religious history of Egypt, but they were not actually presented in coherent written form until the Greek Herodotus referred to them after his fifth-century BCE visits. Plutarch presented the first coherent versions in the Greek language in the first century CE, long after the peak in Egyptian culture. From what remains in Egypt today it appears that these myths must have been incorporated in the long ritual celebrations led by the priesthood and frequently held throughout the country. Both the ceremonies and the stories they told are referred to in the many illustrations carved or painted on the walls of temples and tombs over a period of two thousand years (figure 1.1). The inscriptions and figures continued to be the major illustrations used through at least two significant social and political upheavals of the whole country, and they emerged once again as major themes of art, architecture, and literature at the very zenith of the society in the New Kingdom of the Eighteenth to the Twentieth Dynasty, circa sixteenth century–eleventh century BCE, about the time of the biblical Moses. These myths are now recognized as a substantial source of both stories and imagery used in early Greece and adopted in the succeeding Christian societies.2 Such a succession is almost unthinkable in today’s world without written texts.

Myths and storytelling must, in fact, have been essential elements in the development of societies everywhere, and must have been intentionally employed in this manner. The myths we have chosen are the survivors of many that may have actively circulated for two thousand years or more and entered into the various present-day cultures through having been recognized as important by those who felt responsible for the well-being of the age.

Manuscripts, as well as orally transmitted stories, are vulnerable to the ravages of time. Most of the stories we have chosen to review here were lost to European civilization for nearly two thousand years. They were recovered only as recently as two hundred years ago. Even the languages in which they had been written down were no longer understood. It is, therefore, remarkable that today this situation is so radically changing. Excavations of archaeological material probably began simply as adventures of exploration and treasure hunting; however, by the middle of the eighteenth century CE, artifacts from the whole of the Levantine region had stimulated the interests and efforts of travelers, explorers, and scholars alike. A series of fortuitous accidents led to improvements in interpreting the art, architecture, languages, and religious practices reflected in the many writings that were exposed.

Figure 1.1. The Great Hypostyle Hall of the Karnak Temple Complex, Luxor, Egypt.

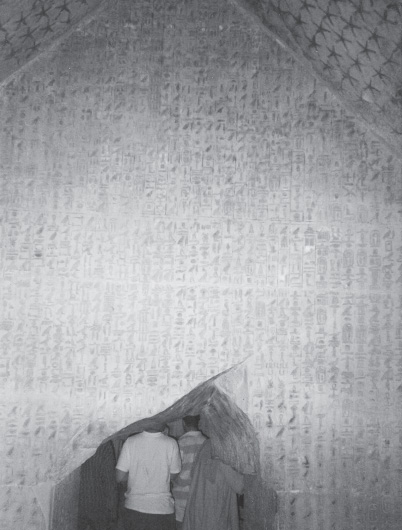

In addition, during the early years of the nineteenth century CE, beautifully detailed descriptions and illustrations of the settings and the visible remnants of ancient structures were created by Napoleon’s famous coterie of scientists, artists, and scholars, who he added to his military expedition to Egypt.3 Still, until the middle of the eighteenth century CE, the purposes for building and decorating the ancient structures of the Nile region were matters of sheer conjecture. Until then, the promise of possible access to meanings had attracted scholars and travelers to the hieroglyphic scripts on monuments and in the cuneiform records found in ancient sites from Persepolis to Cairo. (Figure 1.2 shows an example of hieroglyphs as they appear in an early pyramid.) Their interpretations led to some imaginative results.

Figure 1.2. Columns of hieroglyphs from the first chamber in the Fifth Dynasty Pyramid of Unis, showing the presentation of the Pyramid Texts in the earliest pyramids.

Following Napoleon’s Egyptian expedition, it became clear that the Rosetta Stone from Egypt and the Rock of Behistun from Persia, present-day Iran, each contained trilingual inscriptions, opening the possibility of translation of the material into known languages. By the 1820s in France, the possibilities inspired the work of Champollion on the Egyptian material, and in 1846 in England, Sir Henry Rawlinson published translations of ancient Persian.4 These advances set the scene for renewed activity in excavation, translation, and reinterpretation of much that had been neglected or misconstrued until then. The cumulative result of this upsurge in interest and activity allows us to begin to discern shadows of what was important enough to past ages to have occupied a significant part of the resources of the societies. These remarkable combined efforts now create for us the possibility of comparative study, which has a continually increasing breadth and depth, almost from year to year. We believe that this wealth of new material not only speaks of what was known in the past, but offers inspired wisdom to a world that, while open to new meanings, more often shows itself in danger of losing its sense of values.

Unearthing the Evidence and Methodology of the Initial Study

To truly grasp these ancient myths, we believe that an understanding of both their intent and their content is required, and for this we need a context wide enough to embrace our growing perception of their enduring importance. Some of the tales we study here were first written down by the middle of the third millennium BCE. That is, we are trying to determine the meaning of tales that originated five thousand years ago. This is no simple task. The tales may have passed through major social upheavals in the civilizations through which they endured, which could have brought about changes in the storylines to fit each new society’s needs and expectations. We must also ask whether our Western value system is so different from that of the cultures in which the stories originated that the original intentions of these tales are obscure or indecipherable. Could our perceptions of normal have changed so much over time that important aspects of the tales have been rendered virtually unintelligible to us?

In fact, the reality of changes in the understanding and valuation of basic facts led to the publication of Hamlet’s Mill: An Essay Investigating the Origins of Human Knowledge and Its Transmission through Myth. This volume, which assesses the differences in knowledge and understanding between modern and ancient peoples, has proven to be a major landmark in recapturing meaning from mythology. The authors, de Santillana and von Dechend, brilliantly and patiently expose the consequences that have attended the loss by modern scientists, archaeologists, and artists of an understanding of even the basic facts of the night skies, so well-known by the peoples of early civilizations. They show how our modern ignorance of these common phenomena has led to a complete misconception of the knowledge and motivation of the ancients.5

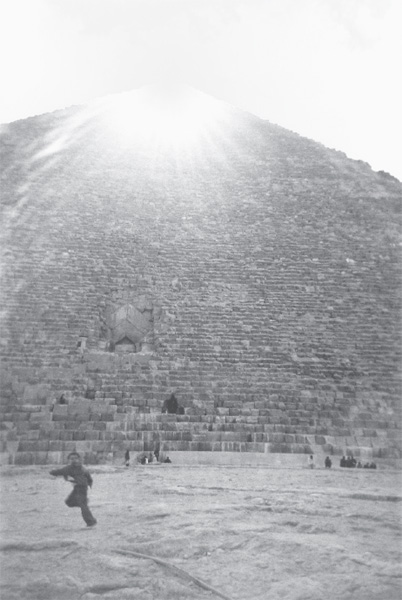

The authors proceed by tracing intricate details of the evolution of the story of Hamlet, so well-known to English-speaking audiences from Shakespeare’s play. They follow it through a number of earlier literatures of Europe and point to the evidence that ancient civilizations, especially those that developed under the clear sky conditions of the Levant, were able, perhaps compelled, to measure the positions and times of the rising and setting of the stars and planets that occupied the night sky in relation to the movements of the daytime, life-giving sun (figure 1.3). It was in these circumstances that humans must have first perceived the seasonal path of the sun and both the night and daytime paths and forms of the mysterious moon; the more erratic patterns of the planets; and the mysterious annual movement but near stability of the distant stars—all of which are so apparently and inevitably intertwined with the mysteries of the birth, life, and death of humankind. In a remarkable tour de force, they demonstrate something of the power of the necessary common background among different peoples, accounting for the various dramatic versions of the stories that resulted.

Figure 1.3. Sun at noon sighted at the top of the Great Pyramid at Giza.

They draw particular attention to the ancient awareness of the very large-scaled and mysterious celestial phenomenon gradually becoming better known by us as the precession of the equinoxes. They lead us to appreciate the effect that these common observations had on ancient peoples, who found in the highly complex but vast and regular pattern of celestial movements the basis for the characters of the many levels of gods on whom humankind depended and with whom humans lived—exposed and vulnerable. De Santillana and von Dechend’s careful study of myth reveals that the knowledge of vast heavenly movements had persisted over millennia.

De Santillana and von Dechend then demonstrate how the loss of present-day concern with all but the more dramatic events in the night and daytime sky makes it difficult for modern humans to appreciate the power of this original basis for understanding myths. Our difficulty in empathizing with the importance that ancient humans found in the influence of these inexorably changing and overriding external phenomena on problems of social and political interactions dulls our sensitivity to the remarkable insights into human interactions and perceptions that are embedded in the tales. We therefore need to question whether this ancient attribution of causes really differs from or is inferior to our current faith that social and political structures can be held responsible for events in our present-day world. Could an understanding of the more vivid apprehension by the ancients of the influences that affect us help us be more sensitive to the subtlety of cause and effect of events among our own societies, countries, people, and individuals?

The perspective afforded by Hamlet’s Mill also helps us appreciate one of the puzzling practical problems set for us by the symbolic content of myth. Knowing that an understanding of solar and stellar cycles was common among early civilizations makes it possible to accept that tales told in quite different and separate societies could have a strong similarity of themes, even without evidence of cultural contact among them. It also explains the parallelism and persistence of myths that arose throughout the ancient near and Middle East, in Sumer, Egypt, Babylonia, Assyria, Palestine, and Greece. Evidence of actual physical contact has only recently been confirmed in a number of cases by scattered fragments of literature found among archaeological remains.6 Only in the past twenty-five years has it become widely known that fragments of writing found at Amarna from the reign of Amenhotep IV, commonly called Akhenaten, in the Eighteenth Dynasty of Egypt, contain snippets of the Babylonian versions of the early Sumerian story of Enkidu’s descent to the underworld.7

Such findings add to the remarkable stories of discovery and the accounts of difficulties of acceptance of interpretation of the myth of Gilgamesh that are described in the introduction to the modern translation by Mitchell.8 He points out how even the facts of parallelism between the ancient Sumerian and Hebrew versions of the story of the Flood were for a long time resisted in Europe, fueled by the persistent prejudice that stories told in Christianity must have originated directly from special inspiration within it. In parallel with this, we can perhaps appreciate the limitations in our present ability to accept new points of view about familiar myths; thus, the need for this chapter in preparing the reader for what is to come.