and the Muses

The ad in the San Francisco Chronicle was basically truthful. “Nothing like this has ever happened before. Not, as in Denmark, a pornographic display, but an artistically free festival … where filmmakers publicly project their visions of human behavior, including in that range the sensual and the sexual.’’

The advertised event was the First International Erotic Film Festival, which took place in San Francisco on December 1–6, 1970. Its sponsors spent about twenty thousand dollars and took in about fifteen thousand, but aside from losing money, which they expected, they considered the Festival a success. They had wanted to encourage serious filmmakers to work on films that would be in some sense erotic and also artistic, and to provide a setting in which dirty movies could be considered as works of art. Most of the filmmakers who entered last year’s Festival seemed to be inhibited in various ways about sexual subject matter, but an institution has been created and this year’s films may be quite different.

The promoters and the filmmakers had a qualified success, but I am sure most of the audience went away disappointed. What they expected, I believe, after talking with a number of them, was an amalgam of pornography and art. They hoped for erotically arousing films that would also be edifying experiences. What they got was mostly standard underground (‘’New American Cinema”) films.

Because the sponsors had chosen not to define “erotic film,” anything the filmmakers submitted was considered. There was some nudity and some sex, often presented with a full range of visual razzledazzle—superimposed images, split screen and other optical printing effects, color solarization. There were several primarily humorous films, and several in which no human body appeared. And there were a few commercial sex films.

The audience had reason to expect a combination of art and porno. Leo Productions and the Sutter Cinema, the sponsors of the Festival, were just names to many of the filmmakers who entered. But in the Bay Area they are well known for hard-core pornography with artistic pretensions. Leo makes them, and the Sutter Cinema shows them. One Leo film exhibited at the Festival showed a girl masturbating while sitting on an American flag. If she had been sitting on a bed in a standard porno motel-room setting, that would have been mere pornography, but if she sits on an American flag, we may choose to believe that the filmmaker, whatever else he was doing, was Making A Statement.

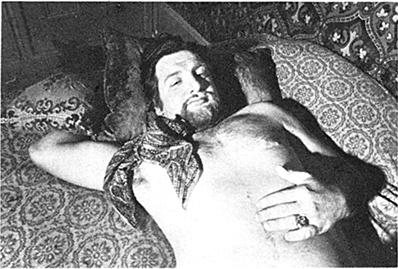

“Pickett: tonight’s guest in a Procrustean bed.” From Evergreen Review No. 88, April 1971.

Leo is headed by Lowell Pickett, thirty-six, and the Sutter Cinema by Arlene Elster, twenty-nine, who are business associates, close friends, and prominent members of the Sexual Freedom League. Their commitment to sexual liberation goes beyond the fact that they make a living by selling sexual images: when I first met them, more than a year ago, Pickett was holding Sexual Freedom League orgies in his home on Friday nights, and Elster was conducting a Wednesdaynight discussion group on outstanding pornographic books.

Aside from the personal reputations of the sponsors, there is the San Francisco scene in general. At this writing there are more than twenty theaters in San Francisco that show hard-core pornographic films, and several public places where live sex shows are put on. Variety recently reported that San Francisco is the hardcore capital of the world. That may be exaggerated, but an erotic film festival in San Francisco might produce very hot stuff indeed.

The advertising also mentioned four thousand dollars in prize money, with two thousand going to the best film in the Festival, and the three judges could hardly have been better chosen to support the audience’s hope for a marriage of art and porno. Arthur Knight, film critic for the Saturday Review, is coauthor of a long-running series of Playboy articles on sex in cinema. Maurice Girodias, of Olympia Press, publishes exactly that combination of hard-core pornography and mostly half-baked artiness that the Festival’s sponsors strive for in their own films. Bruce Conner, artist and filmmaker, is not especially associated with sex in film, although his Cosmic Ray, which showed a naked woman with clearly visible pubic hair, was pretty daring for 1962.

Last, there was the theater. The Festival was held at the Presidio, a well-kept art house in an expensive residential neighborhood. For some time it has specialized in films of sexual interest that are at least a cut above grind-house cheapies. It is too far away from downtown to attract the usual porno crowd: businessmen taking a long lunch hour, salesmen killing time, tourists who don’t know where to go, servicemen on leave. When the I Am Curious films played in San Francisco, they played at the Presidio, and it was an ideal choice for the Erotic Film Festival.

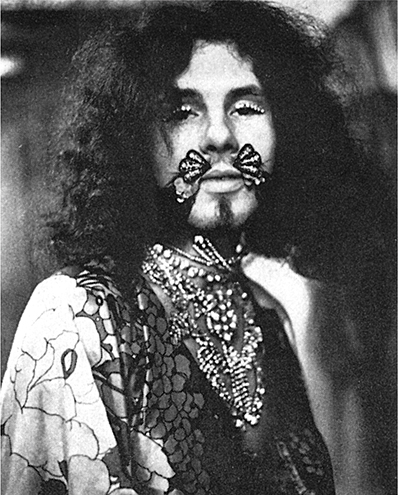

Opening night was crushingly well attended. There were some of the middle class and middle-aged, and some of San Francisco’s nobility and gentry in search of titillation provided under respectable auspices, but it was mostly a young, long-haired, marijuana-smoking audience, with almost as many women as men. The underground press turned out en masse, to report and to freeload. Sitting behind me were two people who said they were from Zap Comix. When I asked if Zap reviews films, they said it might in the future. The aboveground press was also there. Film people came. Almost the only thoroughgoing exhibitionists in the crowd were the Cockettes, a troupe of female impersonators who do satirical material.

“A Cockette. ‘The only authentic exhibitionist.’” From Evergreen Review No. 88, April 1971

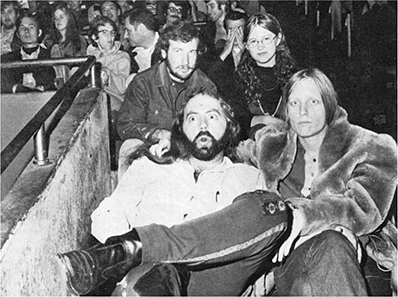

“Festival Audience. ‘It applauded, booed, hissed, yelled “Right on!” and “Bullshit”’” From Evergreen Review No. 88, April 1971

The Festival audience was extraordinarily responsive; it applauded, booed, hissed, and yelled, “Right on!” and “Bullshit!” On opening night the last film was a commercial sexploitation number, The Zodiac Couples, that ran for an agonizing sixty minutes. The audience engaged the film’s narrator in a sprightly dialogue, and those who did not walk out—there was a lot of voting with the feet—had a good time laughing at the film and applauding their own wit.

Partly because of the diverse nature of the entries, and the lack of a definition of “erotic film,” the judges decided that no one film was so far ahead of all the others as to deserve the two thousand dollar prize, and so they divided the money equally among four films. Dead-heat first prizes went to Scott Bartlett of San Francisco for Lovemaking; to James Broughton of Mill Valley, Cal. for The Golden Positions; to Karen Johnson of Northridge, Cal. for Orange; and to Michael T. Zuckerman of New York for Secks. According to a statement issued by the judges, these decisions were unanimous.

It was more difficult to agree on the second prizes, five awards of two hundred dollars each. Two judges voted for each film; the third disagreed, often violently. Second prizes went to John Dole of San Francisco for The Miller’s Tale; to Victor Faccinto of Sacramento, Cal. for Where Did It All Come From? Where Is It All Going?; to David Kallaher of Cincinnati for Verge; to Dirk Kortz of San Francisco for A Quickie; and to Carl Linder of Los Angeles for Vampira.

There was too much disagreement to award third prizes to particular films. The rest of the prize money, one thousand dollars, went to Canyon Cinema, a West Coast cooperative that distributes films by many of the entrants, “to encourage the production of more—and better—erotic films in the Bay Area.”

The four first-prize films were a various lot. The judges stated that Scott Bartlett’s Lovemaking “most closely approximated their idea of what an erotic film could be—an imaginative, suggestive, nonclinical evocation of the sexual act.” (What kind of fascist nonsense is this—the sexual act? Gentlemen, there are an awful lot of sexual acts.) The film began with a few squiggles of light moving on a dark screen, and I wondered if I was going to see a wholly abstract work. But then the screen was filled with what I took to be the skin of a naked woman—a small part of a naked woman—standing under a shower. From the sound track we heard a rushing of water.

Later—I am describing a few of the more identifiable pictures Bartlett has made for us—we see what I took to be a woman’s vulva, photographed upside down, with fingers stroking it. Still later the lower half of a woman’s torso, with the head of a man apparently kissing her vulva. The whole film ran to abstraction and partial views of the body. For me the most direct and least fragmented suggestion of “the sexual act” came from the sound track, which seemed to consist largely of cries by an excited woman. I found Lovemaking visually and aurally agreeable, but it is neither a turn-on film nor a statement about sexual passion. Bartlett avoids things, which is perfectly all right in a single film, but disturbing to me if that film is presented as the judges’ ideal of what an erotic film could be.

Karen Johnson’s Orange, which ran for only three minutes, began with a lovingly photographed closeup of the skin of an orange. The camera’s gaze moved around the orange and settled on its navel. A thumb tip appeared and pushed into the navel. Other fingers joined it and tore open the orange, broke it into sections, and put them into a full-screen mouth which ate the orange. At the end of the film the audience burst into explosive applause.

That was all. The use of extreme closeups in sharp focus produced a sensual if not sexual feeling that was quite compelling, and it is possible to think of eating an orange as symbolic of a sexual act. I liked it myself. Bruce Conner said he thought it was the best film in the Festival, and it was warmly received, but I would still rather not think of this year’s Festival as being dominated by a magnificent film of the opening of a champagne bottle.

The Golden Positions, by James Broughton, did not purport to be an “evocation of the sexual act” or a statement about Eros. As Broughton quotes Confucius, the golden positions are standing, sitting, and lying, and the film explores the visual possibilities of posing and moving the human body. Among the credited performers were several dancers, including Ann Halprin, who did a charming and funny vaudeville bit.

At the beginning, we see a man’s naked midsection, with the navel at the center of the screen, and we hear a narrator’s voice saying, “Let us contemplate.” Contemplate—naveI—get it? The camera backs off, the man’s whole body appears, and the narrator says, approximately, “The subject of our lesson for today is the human body, which is the proper study of man and the measure of all things.” I may have garbled the words, but I have retained the tone, which is deliberately banal and sententious.

Broughton presents a series of poses and brief intervals of dance movement, sometimes humorous, sometimes humbly admiring of the body, and sometimes hard to figure out. The narrator gives us a parody of a religious service, and the musical accompaniment gives us parody hymns to the body. For me that sound track was unpleasantly distracting; sophomoric jokes can be very funny, but they pall after a time.

That is also my feeling about the film as a whole. The Golden Positions would have been a stunning job at seven minutes and impressive in a stately way at twenty minutes. At its actual length, thirty-two minutes, it is a laudable failure. Its virtues and faults are those of Pacifica Radio and educational television, and its appeal will be to much the same audience, which seems to prefer having its esthetic experiences certified by great expanses of dignified boredom.

The remaining first-prize film, Secks, by Michael T. Zuckerman, was described by the judges as “abounding with humor and fertile with suggested points of departure for at least half a dozen more pictures.” In the first of several enjoyable though hardly unified bits, a naked girl walks out of an apartment building and into an open convertible. She is driven around New York City by a chauffeur, and the other drivers don’t notice. The sky doesn’t fall, traffic doesn’t jam, New York doesn’t pause in its unseeing busyness.

Among the cast credits I noticed the names of Donna Kerness and Bob Cowan, two superstars from the stable of filmmaker George Kuchar, and in its tone Secks often reminded me of Kuchar’s work. But there is much more visual trickery in this film, and Zuckerman seems to have set out to show everything he could do with the medium in a single film. I hope the next Zuckerman film I see is less fertile with suggested points of departure and rather more pulled together, but Secks had some very nice moments.

Some other films deserve mention. I had a good time watching Andromeda by George Paul Csicsery of Berkeley, which suggested the world of classical mythology. Stamen, a male homosexual film by P. Lane Rapère of San Francisco, was full of superimposed and color negative images, but maintained a warm emotional tone in spite of its visual bravura. Jerrold A. Peil, also of San Francisco, gave us How To Make, a “satirical guide to the making of pornographic movies.” YOU NEED SYMBOLISM, says one title, and we see three people fondling a cat; YOU NEED SUSPENSE, says another, and the screen goes blank for a while.

Two films I found hateful but nevertheless respectable were Cybele, made in Japan by Donald Richie of the film department of the Museum of Modern Art, and The Christ of the Rooftops, by Herbert Jean deGrasse, of Comptonville, Cal. Richie’s film, whose performers appeared to be dancers or dance-trained actors, has the obtrusive visual beauty provided by its Japanese setting. The action, presumably based on ancient myth, and described in the titles as a pastoral ritual in five parts, runs to a comically portrayed sadomasochism. A very odd job. The Christ of the Rooftops is, among other things, a crude effort to illustrate that familiar piece of barroom wisdom, “If Christ came back today, they’d crucify him again.” DeGrasse handles this theme less well than Dostoyevsky, but his film is often boisterously funny in spite of what it is trying to say.

On the whole, the quality of the films was respectable, and the sponsors of the Festival are to be thanked for putting on a good show of underground films even if they disappointed the lay audience. It would have been better if more films had been entered. The sponsors expected at least five hundred films and were prepared for a thousand or more; in fact there were about eighty. Conner said that about ten percent were worth looking at as films, which he considers a normal percentage for an underground film festival. Perhaps unfortunately for the audience, fifty percent of the entries were shown at the Festival, rather than Conner’s ten percent or less.

Entries had been solicited from filmmakers’ coops, university film departments, and other likely sources, but the invitations went out about a month and a half before the judging, and that turned out to be not enough time. Films were still being received after the Festival began. As for the international aspect, although films were received from Australia, Brazil, and Canada—one film from each country—I would hope for more foreign films next time. Post mortem discussions suggested that simply transporting a film from one country to another often required more time than was available, not to mention the possibility that Customs might delay some films.

This year’s Festival is scheduled for November, and the call for entries will go out six months before the deadline, a period intended not only to make international participation easier, but also to allow films to be made especially for the Festival. Already more than fifty filmmakers have called up the sponsors to ask about the 1971 Festival, and a satisfyingly larger number of entries seems likely.

Before the 1971 Festival takes place, I’d like to express a few general observations about this year’s films and some hopes for the future. Many of the observations are concurred with by Bruce Conner, with whom I discussed the Festival at length; my preferences and hopes are my own.

The invitations specified that entries might be in 8mm, 16mm, or 35mm format, and, if 35mm films are wanted, I’d like to see entries of the caliber of Bergman’s Smiles of a Summer Night, or the Japanese masterpiece Thousand Cranes. This year there were no feature-length theatrical films from major producers.

One reason why Lowell Pickett and Arlene Elster sponsored the Festival is that they cannot find many dirty movies that are any good at all artistically. They commission independent filmmakers, some of whom have done nice films on nonsexual subjects, in hope of getting something better than routine porno. They want to occupy a position like that of Maurice Girodias in Paris in the 1950s; much of what he published was garbage, but he also published books of real literary merit. Most of what Arlene Elster shows at the Sutter Cinema is garbage, but she is quite eager to find the cinematic equivalents of Beckett, Burroughs, and Nabokov. After much disappointment, she feels that filmmakers are ashamed of sexual subject matter and do not really believe it can be treated artistically. The Festival is an attempt to break down that mental resistance.

In Oriental cultures there is a tradition that allows direct sexual representations to be considered high art, and in Japanese prints the artist is allowed not only to show the sexual organs plainly, but to exaggerate their size. The films shown at the Festival suggested to me that many filmmakers believe that hiding or blurring the outward appearances of the genital organs is art, while showing them clearly is porno. Undoubtedly some of this runs parallel with the tendency toward abstraction in twentieth-century painting and sculpture, but I think a lot of the abstraction I saw was modesty—or shame—disguised as an art.

Another reason for the prevalence of visual dazzlement is that many filmmakers seem to identify themselves with a bag of tricks. I know how to do superimposed images, runs the reasoning; I like superimposed images; therefore any film I make is going to be full of supers. In any erotic film made by some of these people, Venus would be merely tonight’s guest in a visual Procrustean bed.

Which leads me to some of the limitations of the underground film. People who dislike pornography complain that the characters have no depth and no history, and do not exist in any seriously developed psychological or social context. They are bodies, and they perform sexual acts in an unidentified bed. The same complaint can be lodged against most of the films in this festival, although their creators might be insulted at being compared to pornographers.

To mention the most brutal limitation, character development seems to call for dialogue, which requires synchronized sound, which requires equipment most underground filmmakers cannot afford. Another limitation is that while Ingmar Bergman is a writer, most underground filmmakers are not. They generally do not have trained actors at their disposal. One way around this limitation is to use dancers and dance movement, as Broughton did quite successfully in The Golden Positions. Another way to achieve sustained action without creating a story out of nothing is to use a ready-made story, as in the film made from Chaucer’s The Miller’s Tale. (But that film had a written narration and used professional and semi-professional actors.) Still another way to organize sustained action is to suggest myth or ritual, as in several other films.

When I discussed this point with Conner, he said filmmakers like to do what they think they do well, and most underground filmmakers think of themselves as photographers and film editors. Not playwrights, directors, or choreographers. We are going to have the visual razzle-dazzle for a long time, and some of it is marvelous.

But, if I may address myself to Santa Claus, in this year’s festival I should like to see less embarrassment about sex on the part of the filmmakers. An orange can indeed be a symbol, friends, but so can a cunt. And I’d like to see more interest in what the performers are doing and why, not just in their possibilities as visual elements. And evidence of a broader spectrum of talents than those of photographer and editor. As for superimposed images used as substitutes for thinking about Eros, and as cheap approaches to the sublime, we had enough the first time around.