‘At Sir Anthony Cope’s a house of Diversion is built on a small island in one of his fish ponds, where a ball is tosst by a column of water and artificial showers descend at pleasure. But the Waterworks that surpass all others of the country, are those of Enston, at the rock first discovered by Thomas Bushell Esquire.’

Dr Robert Plot, Natural History of Oxfordshire, 1677

‘Quaesisti nugas, nugis gaudeto repertis’ – ‘You were looking for trivial amusements – here they are, enjoy them.’

Inscription on people-squirting fountain at Augsberg, recorded by Michel de Montaigne, 1570

WHEN KENELM WAS fifteen, and under the tuition of Bishop Laud, he was given leave to go home for the feast of Trinity, and spent a day riding slowly east across the sun-parched countryside. As he rode he felt freed, gradually, of all the stiff, correct conduct Laud enforced, and their continual, courteous conflict on matters of religion. Kenelm had smuggled a copy of The Odyssey out of Laud’s library and plodding along, sometimes half-sleeping in the saddle, his mind drifted to monsters, whirlpools and mermaids’ tails. But whence did they propagate, if they had no legs?

In Oxfordshire, on the homeward stretch, he rode up through Pudlicote towards the River Glyme and spied a fine church tower and brook. This would do as a place to water Peggy, his pony, whose real name was Pegasus, but who was definitely a Peggy. As he approached, the bells began to ring out.

‘What church is this?’ he asked a woman passing by.

‘St Kenelm’s,’ she said, and left him standing all ablaze, as Peggy cropped the grass.

Such a feeling of special providence is always pleasant, but for a fifteen-year-old boy it was intoxicating. He had heard of the church, but had never seen it before. Well pleased with the form and shape of his church and particularly its solid tower, he surveyed it twice on foot in a circle, and lit a candle at the shrine of his namesake Saxon child-saint, before journeying further into the gold-green countryside.

He paused to cross himself in front of the lichen-mottled megalith at the crossroads, some giant’s old plaything with flowers tucked into its pock marks, and a bowl of milk left at its foot for Robin Goodfellow. A long stately drive, unmarked, attracted his attention and he wondered if it was Neat-Enstone, famous for its pleasure park and water-grottoes, built by Thomas Bushell, seal-bearer to Sir Francis Bacon. Kenelm had heard about its marvellous fountains. He turned his pony into the drive, though he had no invitation, and with the impunity of youth, headed straight ahead at a casual rising trot.

The trees along the drive were alternately tall then squat, so they resembled, to Kenelm’s eye, an Irish stitch. The trees barred the sun rhythmically so as he moved forwards he was dazzled by stripes of brightness, then shadow, brightness, shadow. The drive was quiet but he could hear in the distance, so he thought, a roar of water.

He tethered Peggy and proceeded down a curved, deserted forest path. Sensing he was being watched, and feeling, as teenagers do, that this moment might be of great import for the rest of his life, he removed his hat and ran his hand through his sweat-darkened hair. When he turned the corner he saw an open garden lawn before him, fringed with trees like a stage’s curtains, and hung with a very fine mist, resting on the air. A perfect rainbow arched across it.

Kenelm’s eyes welled at this sign of peace and forgiveness. Soon the rainbow would be dissected by Descartes, and anatomised by Newton, but from where Kenelm stood it was a symbol, mystical, allegorical. He knew, of course, that it was made of rain and sunlight and eyesight, and he knew that what he saw was an artifice, conjured out of carefully created spume. Because he had a mind that liked to understand what moved him – the type of mind that would, by degrees, create the modern age – he decided the water must have been forced through a very narrow fissure to create such a delicate spray, and he wondered how such pressure had been attained.

He thought he heard a laugh, or the rush of water, and turned around to follow the path till he could see, some way off, an ornate dwelling, perched at an improbable angle on the hillside, with rocks below it forming a cataract and tumbling cascade.

He followed the path onwards as it took him back into the hill, towards a fantastical grotto set into the cliff. It had been bricked all about, like a saint’s cave built into a cathedral, but it was still clear that it was nature’s work; no craftsman could obtain these molten patterns in the stone, curves and drips as from a frequently lit tallow candle. Inside the grotto it was cool and peaceful. He sang a few notes, just to hear the echo. Some of the rock-drips were protuberant, like long noses, polished by the action of water on them over hundreds of years. No doubt since the Flood. The villagers probably said a dragon had died here and these stones were formed by its blood trickling through the rock. In some ways it was a more compelling solution than ‘the sustained action of water on a particular rock’.

Crossing a bridge he glimpsed, through the leaves of a tree, girls splashing in a pond – sunlit, laughing, dancing whirlygirls. Three of them were playing catch, the water dragging their dresses as they leaped about. They were of different ages – sisters, maybe. Two more girls were lying talking together on a rock shaped like a lily-pad. He did not like this attitude of being a peeping Tom, so he walked boldly towards the nymphs.

‘One cannot imagine Kenelm Digby being, at any age, not a man of the world.’

E. W. Bligh, Sir Kenelm Digby and his Venetia, 1932

They did not stop to notice him, and he saw that in the middle of the pool, there was an island, and on the island, inside an oversized, open oyster shell, lay a girl.

She was on her back looking bored, with her heels kicking at the shell’s point, and her arms stretched slothfully behind her head. She wore a nymph’s silk gathered dress, which was – Kenelm swallowed – wet through. She did not appear to have noticed Kenelm; in fact, her eyes were closed, but he felt sure she knew he was there. She was the apotheosis of this pleasure ground, the spirit of the place. She was part of the display, exuding sensual luxury and extravagance from all her parts, in her dark tumbling hair, in her amused smiling mouth, in her curved cheek, in her breasts, rising and falling as she breathed. Lucky air, to penetrate her body. He could bear it no longer. Approach her, his instinct told him, accost her! He reached out to do what only a boy would do when confronted with this apogee of beauty – to splash her with pondwater.

But before he could do it, a shaft of water bounced onto the path in front of him, as if aimed by a cannon. And the next second, cold and unexplained, another shaft hit him in the face, slapping him back. The indignity of it! The water techniques that delighted him had now been used against him for a sportive soaking. This was a very trivial garden indeed.

From the house there came a catcall of triumph and a smattering of applause. Kenelm had no sooner regained his composure than another squirt got him in the chest. He fell backwards on his bottom like a toddler, and heard the girl in the shell laughing at him. Her laugh sounded like sunlight on the sea. Would he have a chance to tell her this? They looked at each other in the eye for the first time, and he felt her look echoing into his past and future, through all the caverns of his soul.

For her part, she saw in that one glance that change was possible. Her life need not be spent idly lying in a shell, a job that any plasterwork nymph could do. She became instantly conscious of the dubious nature of her current situation, and decided she must do something about it.

In other words, they noticed one another.

But the people in the house were laughing, and Kenelm saw he was now part of the entertainment, punished as any trespasser would be for enjoying the private pleasure gardens, like a churl in a morality tale who reaches for another man’s wife and finds her shrivel to a hag in his arms. Kenelm would fight the operator of this pleasureground, Sir Thomas Bushell, for this nymph’s honour, any day, with any weapon.

Smiling so as not to betray his feelings, he raised his hat and bowed, offering a graceful surrender and apology. They could see by his bearing and his dress that he was no lout or roaring boy. Soon the host, Bushell, came down to speak to him. After establishing his family and his nobility, which interested Bushell but little, Kenelm asked him many intelligent questions about the manipulation of the water, the contents of a rainbow, and so forth, and Bushell was only too happy to describe the hydraulics, showing him the various water cocks that were turned behind the scenes, and the tricks that could be thrown up by fountains, and the highest they could shoot, and soon the pair were conversing very like equals.

All the while Kenelm was thinking of the nymphs, and wondering if they were kept by Bushell as his secret harem or if they were Ladies disporting themselves in the fountains because it was a hot day. It was hard to say which was more likely. Kenelm fancied there was an air of luxury, a whiff of licence about the place. He asked, as casually as possible, who the dark maid was. ‘Venetia Stanley,’ said Bushell brusquely. ‘My ward.’

Later that day he finished his journey and was home again, sunburned and thirsty. He stabled Peggy, kissed his mother, and played catapult and Jack-a-rabbit with his younger brother, running together into the dead rooms of the house that had been shut up since his father’s execution. He puzzled constantly on the name of Stanley, turning it over in his mind, until, at dinner that evening, he asked his mother if she knew it. Mary Mulsho, the widow Digby, stopped with her soup spoon half-way to her face. ‘Why, Venetia? She was your playmate, your little friend. When her family were staying at the Abbey, your nurses put you together so you would sit there gabbling at one another, all nonsense, of course, and she being older than you would crawl away, but you could only lie there gurgling . . .’

Kenelm went bright red, and told his mother please to stop, but he also felt a deep sense of calm, as if his planets had simply turned in harmonious alignment. ‘She is fallen into a rare dishonour,’ said Mary Mulsho excitedly, forgetting, for a moment, her own despised state as the widow of a Gunpowder plotter.

‘Venetia’s father having lost his faculties, Thomas Bushell has bought her wardship, and keeps her as one of his marvels at Enstone House, like a fountain or a fancy rock. And they say,’ she added with heavy significance, ‘that Thomas Bushell’s friend Edmund Wyld has her portrait.’ She shook her head censoriously, and if that dear brother of Kenelm’s, John Digby, had not at that moment held up triumphantly one of his milk teeth, which had just fallen out, and wanted praising as he beamed gappily at them, then Mary Mulsho would have remembered to forbid Kenelm from associating with his former playmate.

Instead, Kenelm rose expressionless, and went calmly upstairs, until reaching his bedchamber he threw himself down on the floorboards and started performing exercises, fencing thrusts and lunges, lifting himself up by his forearms to the roof-beam, again and again. He used as weights the precious stack of books in his bedroom, the heavy volume of Ephemerides and the Hebrew Bible. He needed to build up his strength before he saw Venetia again. He worked on his learning, too, to make himself worthier of her love, and was very often lifting one book at the same time as reading another. It felt the right thing to do as he passed the unbearable time while waiting to see her. And so it was that Mary Mulsho spent the summer believing her son was riding out every day to make an antiquary’s record of the standing-stones and monuments in the district, as indeed he was. Apart from every hot day, when he went directly to Enstone House, to talk mechanics and hydraulics with Sir Thomas Bushell, and gazed discreetly, across the ponds, towards Venus in her shell.

‘It is believed Sir Kenelm brought edible snails from the South of France for Venetia, as these were thought to have curative properties . . . It is true that this species of snail is still occasionally found in the district.’

Stoke Goldington history society, 2013

THE HOUSEHOLD WAS in chaos, packing for London. Upstairs, Venetia was standing at her closet.

‘Red shoes, red waistcoat, Bible, sal aromatica . . .’ she said, passing the items to Chater, who stood behind her in black priestly vestments, his big sad eyes bulging, the better to look over her shoulder into her closet. He loved seeing all her apparatus of womanhood, the pads which shaped, the strings which bound. It was marvellous to think how this stuff came together to create a lady.

‘Rosary, sweet bags, pearls to be restrung. Will you have command of bringing with us my writing things, Chater?’

Chater was relieved; as their private chaplain, he had been hopeful but not certain he was going with the Digbys to London. He had feared being put in charge of the spiritual care of the children and servants here at Gayhurst.

He and Venetia had been each other’s boon companions when Kenelm was away, spending days together making designs for Venetia’s hats, debating questions of philosophy, or gossip, telling each other poems and songs. Chater had good taste, and he was cultivated – he had even been to Rome. It was said he might make a cardinal one day. He was one of the few Catholic priests in England legitimised by a grace note of pardon from the Crown, and he considered the Digbys were as fortunate to have him in their service as he was to serve. At Gayhurst he was the perfect companion for Venetia’s closet, full of advice on colours, styles and fabrics. She had her lady’s maid – but for urbane conversation, and modish judgements, Chater was invaluable. And while Venetia enjoyed receiving his advice, to contradict it gave her even greater pleasure.

His main calling was to save their souls at prayers, but he also made her laugh. He called Buckinghamshire The Void, and all those friends who would not come and visit he called Avoiders. She wondered if his sharp tongue turned against her in her absence.

‘We must finish the new Devotional Tract very soon,’ she said, reprovingly.

We? thought Chater. Pah. She means me. I write all her Devotions, every word, and then when they are circulated under her name, she forgets I had anything to do with them and believes the lie of her own authorship. My lady can persuade herself of anything. She is quite, quite magnificent.

Venetia continued listing her choices. ‘So, the sea-green, the farthingale in case the Queen still favours them, the fur hood . . .’

‘This blue silk would do you very well,’ said Chater, picking out one of her dresses and holding it up to his body.

‘The taffeta, the curling tongs . . .’

‘But this is the blue silk that corresponds with my lord’s blue silk.’

‘Yes, Chater, but I do not like it any more.’

‘It suits you so well,’ he said, putting his hand on his hip and stroking the full skirt.

‘I do not like to wear it any more.’

‘It was commended mightily at court when you first announced your marriage.’

‘It pleases me no longer.’

‘Soft, my lord’s horse comes, blue caparisoned, his trumpeter’s cordalls also, and his girdle, bridles and banners – then my lady following on wearing this correspondent colour—’

‘Stop ye,’ she said in a voice full of passion. ‘It does not fit me, Chater.’

He looked at his shoes.

‘It shows too much of me here, and here. It is immodest. There used to be less of my person, and now I can only wear it on its loosest girth and so the dress has none of its shape and purpose. I feel foolish in it. I am grown more like a woman, Chater. I like my new person. In some ways I believe, after all these years of compliments, I am only finally, now, become a beauty.’

Chater made a small intake of breath. Oh, he adored her. Such lies she told, with such conviction.

‘I used to look at myself in my glass, every hour – more. But I am grown in understanding of Venetia, and, yes, I say – I like her.’

His jaw twitched as if he suffered from keeping quiet.

‘I feel I walk solidly upon the ground now . . .’

She is right in that respect, at least, thought Chater, who could not suppress a smirk.

‘Perhaps because of the love of my boys and my husband. But to wit: stockings, one pair of white, one scarlet . . .’

Chater decided this was his opportunity. He had been waiting for it for some time. He took a deep breath, made his voice low and matter-of-fact: ‘My lady has not been keeping Fridays for fish.’

‘No, she has not.’

‘She has not fasted neither.’

‘I have been with child.’

‘John is almost suckled, my lady. The wet-nurse has been here a year. We are all corpulent beings in the eyes of God, and the purification of the flesh by fasting would be remarkably beneficial to my lady’s . . . spiritual progress.’

Venetia threw a fiery glance at him. Traitor. Kneeling, picking up her old slippers in her closet, she fancied they were a tiny person’s shoes that would never fit her again, and she felt a new thickness to her hands and wrists, and thought how typical, how characteristic it was of Chater to tell her the disquieting truth. He was very like a salamander who would tell no lies, even if he burned. He was a good friend, but oh, he had teeth for biting. She managed to speak quite naturally.

‘Black jet bead cross, a present from my lord. I think I will leave that here. My Dutch fan, yes; my old kirtle, no. Chater, please take the things down to Mistress Elizabeth. Tomorrow you must advise me on the fasting that my spirit so requires.’

‘I will look at the liturgical calendar. There are a few important saints’ days next month.’

‘I think a full day’s fasting sooner rather than later, no?’

‘I am, as ever, impressed by my lady’s commitment to her faith.’ Chater bowed.

‘Go on, sir, go on with you.’

With a little snort, Venetia pinned back her hair cruelly and screwed open the jar on her dressing table containing her summer night-time face cream, a bright turquoise preparation made of verdigris, boiled calf’s foot, myrrh, camphor, borax and finely ground seacockleshells, which she rubbed violently over her face.

Poor Chater. She supposed it was not very fulfilling for him, living here in The Void, so far from his Popish friends and brothers. Letters from Chater’s mentor Father Dell’Mascere had arrived so frequently at first, each one putting him into a radiant good temper, but then the Father’s letters came more scantly, and now not at all; Chater was losing his friends and taking the pain of it out on her.

It was darkening, and she had the sense of losing another day. Down on the east lawn she could hear Kenelm huff-puffing as he ran about the garden, skidding and back-tracking on himself, chasing the over-sized snails that raced away, leaving silver skids. Time was slippery for Sir Kenelm, who surfed its eddies and slip-tides. His snails moved super-fast.

Wheeling and diving after them, he called out to young Kenelm, who although he was only six years old, understood that his father was highly unusual. And yet he panted back and forth obediently in the half-light. ‘They are fast as Mercury tonight!’ Kenelm shouted, as a great whorled murex disappeared out of his grasp across the lawn, skidding towards the dark undergrowth.

‘Let us creep up on them!’ Kenelm whispered to his son, who joined him, tiptoeing, in silent ambush of the bolting snails.

Venetia, sitting on her bed, re-re-read (for the third time) her latest letters, which served for company. One from Penelope was full of detail about her dogs, so boring it became quite amusing. There were two pages of an effusive letter in a smooth French script from Henrietta-Maria’s lady-in-waiting Angelique, saying goodbye as she had been sent away from court. There had been a rout of the Queen’s Oratorian priests and Catholic retinue, who were summarily exiled from the English court when a letter intercepted showed plans for a Counter-Reformation in England. Buckingham himself sent them home. Venetia burned the third page of that letter, where Angelique had written, with dangerous complicity, ‘you and I know this country is not kind to us’. There was no need for that to linger in her closet. There was also a letter in the intense, effortful hand of Lettice Stanley, her little cousin. Had she replied? She could not recall.

She met Lettice at Tonge castle, ten years ago, when Lettice was a young girl who was in love with her, following her everywhere like a spaniel, gazing at her, sending billets-doux and leaving presents of rosebuds and sweetmeats under her pillow. Lettice must be twenty-two now, and she had not married, and yet she had not taken orders either. Lettice was ambitious and full of life, and stayed most of the time in Shropshire with her mother, who was frail, and when she came to court with her father, she would not stop talking, telling hugely long stories about people no one knew, and holding forth on her opinions on the estate of matrimony, of the conditions of the poor, and habits and customs practised in France, all topics about which she knew very little, and soon everyone at court was most fatigued by her. Thomas Killigrew nicknamed her ‘Mistress Furtherto-Moreover’, which was picked up in many quarters, so she was also sometimes ‘Mistress However-Because’ or just plain ‘little Nonsuch-Nevertheless’.

But to Venetia she was still devoted, and what could Venetia do but accept her devotion? Besides, Venetia believed that beneath her anxious, unformed exterior, she was a dear person with a pure and thoughtful heart, and Venetia felt sorry when people avoided her at court, and she encouraged her fashionable friends to think better of Lettice; Venetia cherished Lettice, particularly because no one else did. She was her little Shropshire pony. Venetia had effected various introductions for her, well aware they would come to nothing, but trying, nonetheless; organising for Emilia Lanier to teach Lettice music, so that she might make friends with some of the Queen’s ladies. And because Venetia hoped she might speak less if she knew how to sing.

The fourth letter in Venetia’s closet was a legal missive – the last Will and Testament of Kenelm’s mother. Venetia had it drawn up by their lawyers in London as a precaution against the future. Although Gayhurst and most of the family money had passed to Kenelm at his majority, Mary Mulsho, to call her by her maiden name, still owned land in Ireland, as well as the dower house. Venetia had a secret presentiment that her husband might convert to the Protestant faith, since Catholicism was now his only obstacle to high office. But if he did convert, Mary Mulsho might seek to disinherit him again, as she had tried to once before, when they were first married. So her Will was a sensitive matter that ought to be resolved. Venetia would arrange for Kenelm to visit the dower house, taking with him some other letters, and the Will to be signed, and some tasty present, a game pie or pudding, and Mary would be so pleased to see her son, her golden boy, that she would, most likely, sign.

Venetia was quietly mindful of these matters; she practised daily vital diplomacies which her husband never noticed, writing letters of thanks and love, remembering saints’ days and confinements, negotiating tenancies on the estate, creating friendships and alliances. She hated mundane tasks, which she was expected to perform in order to leave Kenelm free to dream, and she did them impatiently, dropping them at any moment to follow her diversions. She was more likely to drape the room in yellow taffeta than she was to make sure it was swept and ordered. The household was comfortable because she had good servants who loved her. People were what she lived for, company, wit and friendship, whether it be playing with her baby John, or seeking out Chater to show him a new tiffany sleeve or dispute with him about a biblical commentary.

Venetia was wise as Solomon, except when she was foolish. In company she was often silly, laughing as if her head were full of nothing more than pretty bubbles, and she was beloved for it. But the better you knew her, the more you saw her methods, which were often deep.

She heaved herself out of bed, and took her letter box down to join the rest of her luggage, so it would not be forgotten in the rush tomorrow. By the main door she noticed a huge and ominous collection of books, at least fifteen or twenty large bundles tied together with string. For a second she could not understand what they were doing there, and then she was shocked when she realised that Kenelm wanted to take them – all of them – to London, though Kenelm’s bibliomania should not have surprised her any more. She knew what he would say.

‘My darling, if I am without my private library I am less of a man. It is the apparatus that keeps my mind revolving, like the planets that girdle Saturn. I must take all these, as I cannot tell which books I may need next for my Great Work, for my poetry, my travels, my experiments in Hydrogogie, the study of water-works . . .’

La, la, la, thought Venetia, as she climbed the stairs back to bed. Well, this makes my great trunk of beauty seem a little less. I should have packed my second-best cape and some kirtles had I known the coach would need an extra pair.

Although her task of packing for court was done, she felt less prepared than ever, less able to face those inquisitive eyes and assessing tongues. Chater had made her feel no better this evening. She wanted some new project to consume her, as her love for Kenelm and then her babies had consumed her. Perhaps she should become devout – a hairshirter with a scourge always in her hand. She could minister to the poor, and catch the plague for her pains. Or perhaps she should turn bibulous, a mead-swiller or ale-sot. It would blunt her boredom, and lift her thoughts, but she had not the taste for it.

As the sky condensed to indigo, and Kenelm skidded after his giant snails in the last of the light, Venetia remembered there was a plate of stale quince comfits in her bedside cabinet, and with bored, then relishing bites, she munched them one by one till they were gone.

‘Imagination is more important than knowledge. For knowledge is limited, whereas imagination encircles the world.’

Albert Einstein, 1931

Kenelm lay sweating, victorious from his snail-chase. His snails were in their snail-urn, a huge pot he kept for their containment, until he cooked them up with rosewater as a stew. A nice hot bowl would be a cheering surprise for Venetia. Young Kenelm had been rewarded for his endeavours by being invited into his father’s study, and father and son were lying in the hammock that hung from its rafters. Sir Kenelm, during his time at sea, had come to prefer a hammock to a bed.

He had decided to attempt to lay a foundation of alchemy in the boy’s mind. It was early to start, but . . . ‘All imaginations are mirrors. Yours, mine, Chater’s. But the alchemist’s imagination is more like a mirror than anyone’s. We see how every thing has its opposite twin, to which it is attracted and repulsed. “As above, so below” is one of our rules. D’you see?’

Inconveniently, a young maid came in to lay the fire for them, and he had to wait until she had gone before continuing with his dangerously simple exposition, which any maid might overhear. ‘Vulgar secrets to vulgar friends, but higher secrets to higher and secret friends only.’

‘What does “as above, so below” mean?’ said young Kenelm.

‘Perhaps it means that we are a looking-glass version of the heavens. Perhaps it means that everything operates according to opposites. But there’s beauty of it. It can mean so many things according to your imagination. It is a precept which you have in mind to guide you as you do your alchemy. Do you be paying attention?’

‘Yus.’

‘We believe in the anima mundi. Everything is ensouled – whether it is the wind or the trees, which are obviously soulful, or something like a jewel or a clock, which ticks or sparkles, and is guided by its own stars.’

Standing by the armillary sphere, which was at his eyes’ height, young Kenelm was gravely tapping it with his finger so the world turned, and turned, and turned. He had an impatient facility for the mechanism that impressed and disquieted his father.

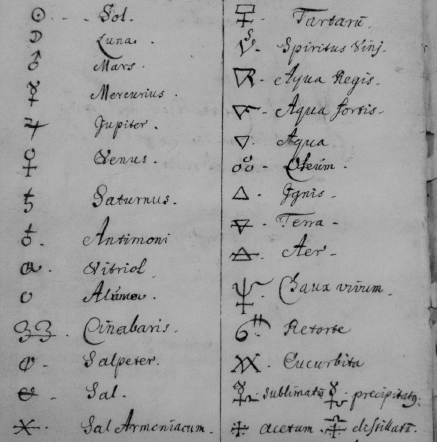

Sir Kenelm got up, standing in front of his limbecks and retorts. ‘Here,’ he announced, ‘are the rudiments of the process by which, eventually, base metals may be turned to gold. First . . .

‘Calcination.’ He rapped the furnace.

‘Solution.’ Ping! He flicked the glass.

‘Separation.’ Shh. He slid a finger down the conical flask.

‘Conjunction.’ He bent on one knee as if to pray.

‘Mortification.’ He pointed sternly to the fire-pan.

‘Putrefaction.’ Rattle! He shook the slop bucket.

‘Sublimation.’ He waved the fingers on one hand.

‘Libation,’ He blew bubbles from his wet lips.

‘Exaltation.’ He held a bowl up ceremoniously.

‘Some stages take a long time: others are swift. We practise them like games of the mind. Each has a hundred different possible outcomes, depending on the conditions, lunar and sublunar.’

Kenelm looked at Kenelm. He hoped he had not gone too far for one so young. The boy’s mouth was moving; he wanted to speak.

‘It reminds me very much of the brewing of ale that Mistress Elizabeth does down in the barn.’

Kenelm’s tufty yellow eyebrows rose very far up, as far as young Kenelm had ever seen them rise. He started putting away his apparatus quietly, humming to himself. ‘Well, sir, indeed. What did I say to you? As below, so above.’