GRIEF MADE KENELM’S mind turn over, like a boat, and—

Let me speake!

Those who would protect him told him he ought to put his mind upon a different subject. He could not sleep, or eat, but existed in a heightened state of consciousness—

Oh, is’t so indeed?

His beard grew untended, his hair unshorn—

Enough from you, who hath spoke so long! Let me have the reins awhile.

Note – The following is taken from Sir Kenelm Digby’s correspondence, including a long letter to his sons, written in the weeks after his wife’s death, 1633:

I can have no intermission, but continually my fever rageth. Even whiles I am writing this to you, the minute is fled, is flown away, never to be caught again.

I have a corrosive masse of sorrow lying att my hart which will not be worn away until it have worne me out.

Not only while I felt the first violence and heate of a passionate and extreme love; but even to her dying day, when I had time enough to observe her and to know her thoroughly, and that almost ten years had converted that which might be thought desire and passion into a solide vigorous and peacefull friendship which (believe me, my children) is the happiest condition and the greatest blessing of this life.

In a word shee was my dearest and excellent wife that loved me incomparably.

Many times she received very hard measure from others, as is often the fortune of those women who exceed others in beauty and goodness.

Although it be not the custom with us in England to have the husbands all the while present att their wives labours, yet she understanding that it was warranted by practise of most other countries – a mann’s strength as well as counsel being in these cases often times necessary – she would never permit me to be absent. She had so excellent and tender a love towards me that she thought my presence, or my holding her by the hand did abate a great part of her paines.

What she won at play furnished her with a certain large revenue, which she gave for the poor. Before she died she disposed of £100 in one lump, to be prayed for.

Whiles she did play, one could observe neither eagerness nor passion in her; no stander-by could have guessed by her countenance whether she won or lost.

Her presence and comportment was beyond all that I ever saw; it would strike reverence and love in any man at the first sight. Her cheeks grew pink through exercise . . . Her blue veins shewed in her forehead . . . Her face could not be expressed upon a flatt board or cloth, where lights and shadows determine every part. Even a little motion in so exact and even a face gave her a new countenance, the life and spirits of which no art could imitate.

[She lost some of her hair] with the birth of one of you boys. Nothing can be imagined subtiler than hers was [her hair]. I have often had a handful of it in my hand and have scarce perceived I touched anything. It was many degrees softer than the softest that I ever saw, which hath often brought to my consideration that [one] may judge the mildness and the gentleness of the disposition by the softness and fineness of one’s hair.

Her hands were such a shape, colour and beauty as one would scarce believe they were natural, but made of wax and brought to pass with long and tedious corrections.

Now towards her latter time she grew fatte, yet so that it disgraced nothing of her shape.

When she had been dead almost two days I caused her face and hands to be moulded by an excellent Master, and cast in metal. Only wanness had defloured the sprightliness of her beauty but not sinking or smelling or contortion or falling of the lips appeared in her face to the very last. The last day, her bodie began somewhat to swell up . . . which ye chirugions said they wondered she did not more, and sooner, being so fatt as upon opening up she appeared to be, and lying in so warm a room.

When she was opened—

Are you sure this is suitable for your readers – your little sons?

When she was opened, her heart was found perfect and sound, a fit seat for such a courage as she had when she lived. In her gall was found a great stone bigger than a pigeon’s egg. In her spleen, two cartiledges, quite extraordinary. There were severall of the most eminent doctors and surgeons of London at the opening of the body. There was but little brain left –

An autopsy such as this was unusual, reserved for deaths which were suspicious or unexplained.

– and this was thought to have caused her the most sudden and least painful death that ever happened.

A cerebral haemorrhage. It is also said she drank a preparation known as Viper Wine.

For to impute any cause of her death to Viper Wine is without any grounde at all . . . Of late she looked better and fresher than she had done in seven years before.

How old was she?

She was born on St Venetia’s day, 19th December 1600. She was designed for my salvation. And if here she was so faire, what will she be hereafter?

Come, sir. Crying will not help her now. Would it comfort you to speak a little more of times you passed together at Gayhurst? Have you returned there yet?

As I rode along, at every step some new object appeared to whett and sharpen my sorrow for they called into my memory a multitude of severall circumstances that had bin between my wife and me in that time which I may truly say was the happiest I ever enjoyed. A tree we sheltered under against a shower of rain. When we were hawking, retrieving of a partridge, I remembered how with admirable agility and without the help of any body she leaped from her horse to save the hawk from a dogg that else had killed her as she sat pluming the quarry in her foote. By heaven, I never saw anything so lovely as she looked then.

For of all the women that ere I knew (and I will except few men) she was most capable of true friendship. Now my mother, who was ever most averse to her in life, can say as much. If my wife had lived, they two had bin upon good terms by this time, for my mother was overcome by my wife’s goodness and had resolved att her next coming to London to have expressed it.

And her funeral?

The funeral was held by night, to enhance sorrow.

At midnight, the bell of Christ Church Newgate tolled the arrival of her bier, dressed with violets. Her black marble tomb was inscribed with copper gilt and set with a bust of her head and shoulders, a good likeness taken from her deathbed, that her beauty might be kept eternally in the mind of the living. The path to the door of the church was lit by flaming torches. Inside, the church was candlelit.

Many hundreds viewed and kissed her corpse. Never was a woman more lamented. Many observed they had never seen so much company. Most came of their owne free motion, for neither the shortness of the time nor the extremity of my passion admitted me to invite any. So many carriages came, Charterhouse was full. Guests included the Prince’s governess, secretaries of state, privy councillors, Aldermen and Sheriffs of London. She was given a Protestant burial.

The only way to have her funeral made public was to make it Protestant, although it meant that Chater was not able to attend, but stayed crying in the churchyard throughout. Amongst the elevated throng in the church, were there many strangers? Those who never knew her, but whose habit was always to go to notable funerals, where they never failed to shed a tear. Those who had waited, years ago, to see her carriage pass, cheering and waving to catch sight of her; those who were convinced of her goodness and kindness to the poor, her virtue as the author of A Mirrour for a Modest Wife.

And what of those who had done her harm? Was there, at the back of Christ Church, Newgate, behind a rotund Norman pillar, a familiar figure, soft and massive, one medicastra by the name of Begg Gurley? For she considered herself a rightful mourner. She was accompanied by her common-law spouse Thomas Leake, he as thin as she was plumpy, as if they had only a certain amount of flesh between them. Her shoulders were heaving as she cried for the loss of her Great Patron, and yet she was grateful that, during her life, she had at least been able to help her more than once.

In the front pews, Olive, crying; Penelope, grim-faced, looking older than the week before; Aletheia, in her high mourning hat and cloak, with pale blue veins delicately painted in oil of Turpentine upon her forehead; Lucy Bright, veiled, her head bowed. The doctors’ account of the brain-spill, the blood-flux in Venetia’s mind which killed her, left some convinced, and others suspicious and uncertain. But all her friends were conscious of an inevitability, a just and fitting drama to her death. It had a certain flourish. To die so elegantly, leaving a husband distraught, a city talking; to die overnight, without blemish or ague; to sit to Van Dyck, after death: if anyone in their little set could pull this off, it would be Venetia. The women mourned and their cheeks were coursed with tears and all, except Penelope, were plumped and dark-eyed from that day’s Drink.

The chief mourner was, by tradition, a woman judged to be of roughly the same age and distinction as the deceased. She walked behind Venetia’s coffin, decked in violets. Her eyes darted and she opened her mouth frequently, as she looked at the mourners around her, as if she was pleased to recognise them and wished to speak to them. One would almost have thought she was enjoying her role, were that not such a regrettable idea. But Venetia could not have wished for a younger or more elevated woman to follow her coffin, for this was Lettice, newly Countess of Dorset.

Ben Jonson took up half a pew with his great bulk. He presented Kenelm with the manuscript of his new poem ‘In Praise of Venetia’, except the first part was not about Venetia, but swiped instead at Van Dyck, repeating that he, Jonson, was a worthier witness than any painter:

Not that your arte I do refuse

But here I may no colours use

Beside your hand will never hitt

To draw the thing that cannot sit—

By this last line he meant ‘the mind’. He found his stride later in the poem:

It were time that I dy’d too now shee is dead

Who was my Muse and life of all I seyd

The Spirit that I wrote with and conceived!

All that was good or great in me shee wean’d

And sett it forth! The rest were Copwebs fine

Spun out in the name of some of the old Nine . . .

So sweetly taken to the court of Blisse

As spiritts had stolen her Spiritt in a kiss

From off her pillow and deluded bed

And left her lovely body unthought dead . . .

For this so lofty form so straight

So polish’t perfect, round and even

As it slyd moulded off from heaven . . .

They were his old familiar rhymes, reheated for the purpose – and the one person who would have spotted the paucity of his invention, and teased him for it, was gone.

Kenelm gave a brief, half-mad funeral address.

Three weeks after her burial, my thoughts tumbled every corner of her grave where her face is covered over with slyme and wormes, or her hart has some presumptuous worme feeding upon it. I wake all bedewed with fears, womanish with weakness. I eat a miserable little pittance and scarcely gett an hour’s sleepe a night.

And the rest of the household – tell us, how does Chater take the loss?

As I sate this morning meditating deeply on my blessed wife’s death (which I do in particular manner every Wednesday) her old servant brought in her picture and sett it downe before me, going immediately out againe without speaking one word; which I perceived his teares that ran trickling downe his cheekes would not permit him to do.

Van Dyck’s painting is in your arms even now?

This is the onely constant companion I now have . . . It standeth all day over against my chaire and table, where I sit writing or reading or thinking, God knoweth, little to the purpose; and att night when I goe into my chamber I sett it close to my bed’s side and methinks I see her dead indeed; for that maketh painted colours look more pale and ghastly then they doe by daylight. I see her, and I talke to her, until I see it is but vain shadows.

Your children are still with their grandmother?

God knoweth it so fareth with me as I am not able to raise any in myself, much lesse to administer unto an other. As it fareth now, I am fitt not for society or relations of others to me.

You are to move house, I hear.

There is such desolation, loneliness and silence in the house where I have had so much company, so many entertainments, so much jollity.

My mother advises me ‘to put a bridle’ on my grief, as we should ‘not sett our hearts over much upon a fading subject’. Many of my discreetest friends advise me rather to seek all meanes to divert my botelesse thoughts from this sad object that can never be recovered; and they chide me because I do otherwise. But for my part I am resolved I will never beguile sorrow if I cannot master it: I will look death, and it, in the face; and peradventure when we are growned better acquainted and more familiar, we shall be good frendes and dwell quietly together.

I conclude from my premises that the golden chain of causes which by severall links reacheth from heaven to earth, beginning with God and passing through the Angels, the orbs of heaven and the planets, downe to the lowest elements, knitting together the intellectual, celestial and materiall worlds, and lapping in eternal providence and her two handmaids, chance and fortune, did bind together my wife’s and my handes, hartes and soules, which death cannot lose, but rather will ferry us over the tempestuous sea of this world to enjoy our friendship in tranquillity and aeternall security where the first knot of it was tied and where the first link of the chain was fastened.

For the first few months my soule has been oppressed with strange agonies. But now I lye quietly, and it lyeth gently upon me.

Sir Kenelm began the dissolution of his library by packing away the Americas.

He turned the pages of his pharmacopoeias, his uroscopies, his prognostics, his Terrestrial Paradise of John Parkinson, and the pleasure he used to take in their engravings was like ashes in his mouth. The seascape murals above him were flat and tawdry, the busts of the Great Authors were plaster bodges looking down on him. There were no Atomes dancing in any sunbeams here. The spirit of Mercurius was no longer in this house.

He packed away his Atlases and rolled his Mappes, although he barely had the strength to lift them.

The treasures he brought back from Florence – no, Siena – when he was seventeen stirred nothing but weariness in him. The perfume of their vellum was too rich for his senses. Livy’s Punic Wars, Cicero, Seneca’s tragedies, Petrarch’s sonnets: without any sentiment, without even a fond glance over his juvenile annotations, he thrust these in the box. They were going to a better place.

Through the painted glass he saw his Peruvian marigold, bent and blowsy, sorrowing in the garden. And yet the chattels in the house retained their freshness, pert and serviceable. He rebuked their callousness, their durability. Her possessions showed no Sympathy, her boots had kept their shape and her playing cards were impervious and bright, though she had been dead four weeks.

His vainglorious library, with its ceiling of clouds, its lovers’ motifs, its sententious aphorisms engraved across the walls: its whole conception and ethos was lost to him. He could not comprehend the babyish happiness he must have enjoyed in order to commission such a den.

There was but one remaining fixture of the library: his armillary sphere, sitting on the edge of his desk, brassy emblem of his former certainty, his mechanical universe. He ran his finger over it so its spheres spun around his little earth, cosseted at the centre of the sky. This model of the universe he now rejected. Galileo the Starry Messenger had sought to destroy his faith in it with reasoning; now life had done that job instead. He lifted the delicate mechanism above his head and slammed it onto the library floor, where one of the soldered brass hoops split resonantly. He scooped up this cracked ribcage of the heavens, to keep as his only trophy, emblem of his broken state.

He shut the door with easy finality, knowing he could always return in his mind.

‘Sir Kenelm donated fifteen trunks of books, comprising 233 codices, five rolls and a catalogue, to the library of Sir Thomas Bodley . . . He also gave “fifty good oaks” from Gayhurst. [for the provision of shelving].

The Index of Middle English Prose Handlist, 2007

Although the journey across the city seemed an impossible undertaking, with his groom’s help Sir Kenelm went down by carriage from Charterhouse to Van Dyck’s studio in Blackfriars. Kenelm’s groom turned the coach round while his servitor left him on the doorstep of the studio, with his potted sunflower and his smashed armillary sphere boxed up beside him. When the studio boy opened the door to the unkempt man in black waiting on the doorstep, he took him for a beggar.

‘If a man can poison his wife with impunity . . .’

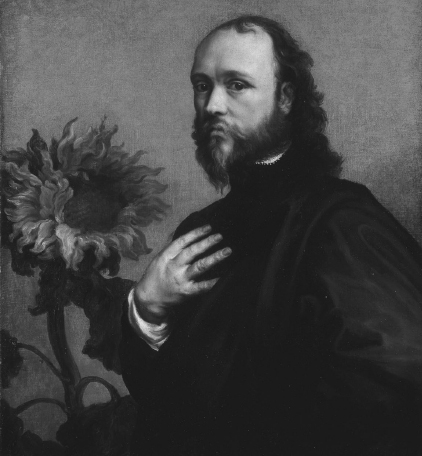

Van Dyck ran through all the possible backdrops: distant mountains, broken columns, rich curtains, garden views, imperial arches . . . Sir Kenelm motioned to his preference, which was a putty-brown drape of cheap material.

‘If a born Catholic can use his improper knowledge of plants and herbs to plot the downfall of his own wife, what harm might he do our country and our King?’

Sir Kenelm barely spoke during their session. Van Dyck imagined him as Harpocrates, except instead of depicting him with the index finger of silence held to his lips, Van Dyck showed how the tendrils of his beard grew almost over his lips, like ivy sealing up a gate.

‘As a wife she was hardly spotless – you can imagine he might do it in a jealous rage. Naming no names ;)’

Kenelm lay his right hand upon his heart, spontaneously, and Van Dyck saw he rested easily in this position of defensive sincerity, and asked him to remain thus.

‘They put poison in their bejewelled rings, see. And then they unclasp, flip and tip it into the wine-cup of anyone they wish to do away with.’

One finger on Kenelm’s right hand was trapped inside his black garb – his little finger. It was a natural detail, infinitely casual, and yet to anyone schooled in Hermetic wisdom, it showed that Kenelm’s powers were in abeyance, his riches lost, and his strength in decline. The little finger was the finger of Mercury.

‘I gave prophecy this marriage would come to no good ends, Lascivious Shee and Whoreson Hee, spawn of a plotter’s loin!’

Van Dyck talked as he painted. ‘So you know about the Sidereus Nuncius?’

Kenelm regarded him balefully.

‘Sentenced by the Papal Inquisition. He is under house arrest. He abjures, curses and detests his theories. In order to live, he has recanted heliocentrism.’

There was silence, except for the gluey sound of Van Dyck’s brush moving, its heavy swirl in the oil pot, and the bright tap of its shaft on glass.

‘She must have suffered the whole night through – just at the very going out of April and the coming in of May . . .’

The all-seeing sunflower knew that both the men were in the Catholic faith. Since his wife’s death, Kenelm had taken the sacrament from Chater, relapsing to the automatic faith of his childhood, the comforting folds of the Marian blue cloth, the heart’s-ease of the Miserere Psalm. Only the Catholic liturgy made sense to him. He would, in time, publicly confess his relapse, his homecoming. Not yet.

In the painting, Van Dyck made Kenelm’s face composed and sanguine, as decency demanded, but he let the sunflower next to him howl and weep, its petals shrivelled by an unseen blight.

Ovid wrote of Clytie, abandoned by her lover the sun-god Apollo, sitting naked and unkempt upon the ground, turning her face to watch the sun as it passed by. In time her legs became roots, her arms tendrils, her yellow hair was torn into petals, and she was transformed into a bloodless plant, a sunflower.

‘He’s said to be a broken man, but where is he? Has he been seen abroad in mourning clothes? Has he given out alms in her name, or set up any town monuments in her honour, or done penance beside her grave?’

Sir Kenelm’s mourning portrait was finished, copied, passed around. Its profundity and novelty were noted. It was not a memento mori; it contained no traditional mourning emblems. It was a problem painting. What shall he do now? What should be done with him?

‘We shall see many more cases like, unless this is brought to trial. And yet the Lord Chamberlain, the Master of the Rolls, the Archbishop himself, none do lift a finger against their friend Digby . . .’

It was high summer, and long days of thirsty drinking gave way to pale blue evenings, by which to wreak rough justice. The whisperings about Venetia’s death had built into a consensus, and the mob found itself with a righteous purpose. Where justice was perceived to have failed, savagery crept in. The mob smashed John Dee’s custom-made laboratory instruments in Mortlake in 1583, and drowned his devil books in the well. The mob hunted the astrologer John Lambe in 1628, hurling pebbles till he was blinded, and when he hid, cornered, it waited outside the door to complete its work when he crept out at dawn.

When angry men came to Sir Kenelm’s home, they stood on Charterhouse green bearing torches, stones and whips, chanting for justice to be done, for his Catholic books to be burned, and for his life-taking conjurations to cease. A local woman who did the Digbys’ washing shouted at them, as she hurried by, that they should feel compassion, but to the mob, Sir Kenelm’s misfortune was a stain, a sign of guilt.

When nightfall brought anonymity, the mob became stronger and more brutal than any of its members. It rammed down the back door with picks and shoulders, and ran into his courtyard, shouting to frighten off the bad spirits working in the service of Sir Kenelm, fearful that he – a murderer already – might wield a musket at them in the dark, or worse, operate his unseen instruments of sorcery. But they had no sport there, for the Digby library was already packed up, the household dispersed, all contents sold, all wishes spent and dreams departed, and Sir Kenelm gone.

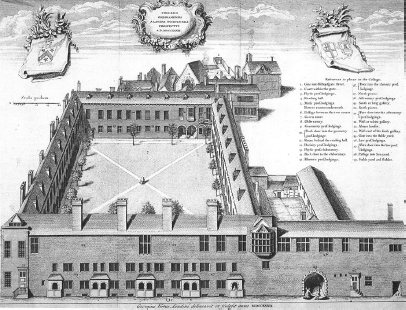

‘Gresham College is an institution of higher learning founded in 1597 under the will of Sir Thomas Gresham and today it hosts over 140 free public lectures every year within the City of London. Its original site in Bishopsgate is now occupied by Tower 42.’

Gresham College website, 2013

At Gresham College, that exalted seat of learning, the porters maintained a jovially paternal attitude to their charges, the professors. The college was founded in Elizabeth’s reign with provision for seven professors, a pleiades of experts in Rhetoric, Divinity, Music, Astronomy, Geometry, Medicine and Law, all supported by stipends and sheltered from the world that they might perfect it. Witnesses to the unseen Microcosmographies of life these gentlemen were, and masters of the circle and the square, with often two degrees from the Universities apiece – and yet between them they gave rise to so many crises, by forgetting to take their meals, losing their keys, exploding their laboratory furnaces, accruing debts mistakenly or falling a-prey to Abraham men and the like, that the only way for a porter to handle a professor was with firm and amused patience.

It was a rich foundation, newly built and endowed, and its gables shone very clean, painted against the ubiquitous coal dust, so it was white, whiter than any other building in the City. For all its eccentricities, it hummed with prestige. Gresham College was established in order to advance commercial interests, and it was far and away from the rowdy Universities. It was a rarefied laboratory of the future. Here, the acuity of human vision redoubled every two years – reaching outwards to the heavens and inward to the dust. The stars were becoming places, not five-cornered specks, and fleas were about to be revealed by Hooke as armour-plated, bristling monsters. The sound of the grinding of lenses, simple and compound, which echoed around the quad on Tuesdays, was the sound of the perimeters of the world extending, coming into focus.

What went on behind the closely guarded stone facade of Gresham College was, to the busy city street of Bishopsgate, uncertain, but occasionally signs of arcane experiments were visible. Small and large transparent spheres of wobbling soap came rising with serene iridescence over the gables of the college, before expiring into a single teardrop on the breeze. Sometimes the chimneys belched yellow smoke, or clouds of turpentine blue, or stank of sulphur. For half a term, the sound of cats wailing in concert emanated from the rooms of the Professor of Music; for years, the clanking of a heavy metal chain could be heard around the college, day and night, while Professor Gunter perfected his Instrument of Dimensurement. This was a favourite with the porters, who loved to recall how this massy great chain had been set up like a hazardous trap-fall all around college, which no one was permitted to move, only step across – and how, after long attempts at its perfection it had made the gentleman’s fortune many times over, being the best tool for surveying distance and calculating land-mass ever yet invented, as well as a sure-fire way to break your neck on a stairway.

Into the college, under the stone-carved grasshopper, which was the founder Thomas Gresham’s insignia, were conveyed many pieces of equipment: empty barrels, used to prove the spontaneous generation of mice out of the air; complicated pieces of blown glasswork, made to order, so that a glass beehive might be constructed, a furtive bee-peeper’s dream (unrealised until Christopher Wren’s residency, twenty-four years later); ores and heavy metals, to be used as medicines.

A file of inkhorns, intellectualists, tech nerds and business speculators waited by the back gate to attend the public lectures once a month. Otherwise, the college was private, hermetic. Professors who passed under the stone grasshopper into the college might spend a dozen years safely inside, shifting the heaviest presumptions with their minds, or blowing thought-bubbles.

In their well-swept rooms beside the green quadrangle they tasted caput mortuum and sniffed mercurial fumes until their skin turned grey. They spun quantities of numbers into logarithms and trigonometry, and cooked up new hypotheses on their retorts and alembics. At night in their cots they dreamed of binary code, and genetic therapies, bandages that glowed when they harboured poison, and magnetic devices that told where bullets lodged in breasts. They sleeptalked across the quad to one another of Voyagers 1 and 2, already bound for other planets, and babies generated out of dishes. With their half-awakened minds, in the grey dawn, they saw their quadrangle and their dining hall on Bishopsgate become, in time, the footprint of one of the soaring towers of the City, built of calculus, and topped with a constantly flashing light, to warn off angels.

One Sunday afternoon, when the daylight was so flat and uniform it seemed as if there was no source of light behind the clouds at all, the college’s peace was broken by a determined knocking. The duty porter rammed open the wooden window in the lodge’s great door, to discover there was nothing there except the top of the head of a girl.

‘Washermaid?’ he asked.

‘No, sir, I am Mary Tree,’ she said, stepping backwards so she might look the porter in the face. Conscious of her Mark, as usual, she was relieved when the porter managed to find it in his heart not to look at her too strangely.

The porter looked down and saw a fresh-faced maid without much to distinguish her from any other.

Mary swallowed. This was the last time, perhaps, that she would need to announce herself and her odd quest to a stranger. She began: ‘I have some business with Sir Kellem Digbaine—’

She broke off and tried again, more slowly. ‘I mean, Sir Kenelm Digby. Is he known to you here?’

‘Well,’ said the porter, with savour that presaged a long and equivocatory discourse. ‘If you mean the gentleman whose hair is long as an hermit’s, who never removes his black mantle, and rarely speaks a word, except to friends, and moreover, demands large quantities of crayfishes for calcification, then perhaps we have an understanding. But as you probably mean only to be meddling with his business of grief, then stay away.’

When you have been travelling for many months with one object in mind, and you come near to that object, almost within touching distance, small frustrations can be unduly discouraging. Mary Tree heard that tightening hum inside her head that told her she was close to crying.

Mary had already been forced to mourn her long-cherished idea of Venetia, and given up for ever her private fantasy of becoming her lady’s maid. Now her whole quest, her long ordeal, was being disparaged by this St Peter, this gatekeeper.

‘Is he here or not?’ she said in a voice that was more high-pitched than she wished it to be.

‘If you mean, is he present or absent, I can tell you that he’s not quite neither, since he’s so distracted by his loss, he’s liable not to hear you, or if he hears you, he may not see you, unless you be a crayfish, in which case he would have you calcified as soon as not.’ The porter looked at her sternly. ‘There are those who would prosecute him for his loss, and drag him through town for a business about which they know nothing, and if you’ve been put up to this by the Lord Chamberlain, and wish to get a false confession out of him, again I say, stay away.’

Mary Tree summoned the last of her strength. She knew she presented a poor spectacle of a girl: weary, with clothes grown shabby from journeying. She was stained across her face, and she could not read or write, but although she had no family, she was friends with all the world. She said with dignity: ‘I find your words an insult, sir. I’m here because he is the Keeper of the Powder of Sympathy, which is the only remedy to heal my kinsman, Richard Pickett.’

The porter’s hatch rammed closed in her face, and she thought her pride had ruined her whole enterprise, until the visitors’ door within the door clicked open, and the porter showed her in.

‘To avoid envy and scandal . . . he [Digby] retired into Gresham-colledge, where he diverted himself with his Chymistry and the Professors’ good conversation. He wore there a long mourning cloak, a high-crowned hat, his head unshorn . . . as signs of sorrow for his beloved wife.’

John Aubrey’s Brief Lives, 1669–96

Mary Tree sat on a step within the quiet embrace of Gresham College, clasping the bound and blackened shard of glass.

The college struck her as somewhere between an almshouse for the insane, and one of the old friaries. A man brushed past her, engrossed in a book that he held up to his face, reading as he walked, pigeon-toed, across the quadrangle. She held the cruel shard to her chest and considered its pathetic bandage, grown brown with dirt. This was the last of her many waits, and it was not a long wait, although it had a semblance of eternity as the light began to be lost from the quadrangle.

Sir Kenelm came moving quickly across the flagstones, his black garments clinging to his body, now so much leaner that he seemed taller. He was carrying the Powder in one hand, and a basin slopping with water.

He barely looked at the girl, but he registered that her eyes were sincere.

‘We shall perform the ceremony on the grass here, so that the healing Atomes may be carried through the air to your – your father, is it? What is his name?’

‘He is my kinsman – but only by marriage,’ said Mary, before clasping her mouth as people do when they wish to take their words back. ‘I mean, he is as much my father as any man in this world. His name is Richard Pickett.’

Sir Kenelm paused. He stopped his hand.

‘Oh, my dear,’ he said. ‘I have received word of him last month. I knew of him a little for his learning of the Caesars. I had a letter which told me of your journey, and – would you like to see the letter?’

Mary Tree nodded first, and then shook her head.

‘I cannot read, so you best tell me.’

Sir Kenelm sat down with her quietly on the cloister wall. He noticed that she must once have had a mulberry stain upon her cheek, which was now as faint as the moon in the afternoon sky.

‘The letter that came, from Devon, I think, from one calling themself a neighbour of the household, makes me think we shall never send forth enough healing Atomes to help him now, for his mechanical physiognomy is beyond our reach.’

‘Has he gone to France?’ said Mary keenly, rising up.

‘No,’ said Kenelm. ‘No, it is further than that he has gone. The letter bid me tell you that he would never rise again, being sick of his wound unto death.’

Mary Tree considered the grey pall that coloured the sky, and shivered.

‘He made a good end of it, passing quickly with a hot distemper upon his heart,’ said Kenelm, who had been moved by the letter.

Mary Tree seemed to be muttering to herself.

‘I should have been faster on my journey,’ she said, more to herself than Kenelm; then, ‘I have let him down.’

Sir Kenelm did not appear to have heard her, or if he had, he did not seem to know what to say. Mourning had clogged that quick facility he always had for talking. But with an effort of will it began to return.

‘If the wound was so penetrating as it sounds to have been, the Cure would not have helped him,’ he said. ‘It treats infection following on from wounds, not the injuries themselves. So your journey might have taken, oh, months, and he would have been no more saved.’

She wiped away a snot-smear.

‘Does the letter speak of a dog called Asparagus?’ asked Mary.

‘I think no, but I will have another look betimes. We shall find you a place here tonight so you can rest a-while and take some sustenance,’ said Kenelm. ‘There are many rooms here in this college, wherein all my world is now. It is a Sympatheticall place. There are sizars and servants here, though there are not many who are as yourself, which is to say, women – but you will find that Goodwife Faldo who runs the household will look after you.’

He saw that this cheered Mary Tree, and he smiled at her with his new, uncanny, counterfeit smile, and whispered, less to her than to the cold and darkling night itself: ‘I have many pertinent designs for the Divine Regeneration of Beings.’

The college quad caught and magnified the whisper, so that it reverberated as clearly as if he had spoken the words in the great amphitheatre at Ephesus.

After achieving sleep for a few hours, Kenelm woke and bid good morrow to his wife. He fancied she was as pale as ever, although, in keeping with his new habit, he moved the painting into the daylight with him when he rose out of bed, holding it to the window to check she had not developed overnight a blue pall, nor any other distemper of the grave.

As she was making up Sir Kenelm’s fire, Mary Tree made a resolution that when Asparagus was conveyed to London, he would be Sir Kenelm’s constant companion. The morning needs of a wolfhound, however base, would be preferable to this daily practice of picture-gazing, which she could not help but consider morbid. In his empty rooms there was precious little else to look on. He would be so much the better when he had that grey-whiskered muzzle to gaze upon every morning.

Kenelm’s bookshelves were bare, and in need of dusting. Mary was surprised that so great a scholar as Sir Kenelm possessed no books. She, Mary Tree, loved to hold the three books she owned, and when he found her looking at her small volume of flower remedies, he took it from her, and then returned it to her instantly, as if it burned his hand.

At the sunlit breakfast table of Gresham College’s great hall, Sir Kenelm instigated a conversation about the custom of the farmers of Saxony, where families who are struggling to feed themselves through a hard winter first toast their grandparents with Meth or Hydromel, then inter them into coffins laid in the ice, where the old people remain frozen until the arrival of more abundant food in spring, when they are disinterred and revived again with more strong drink. The Professor of Astronomy, who was morose after a long night waiting for clouds to part, thought this sounded like an errant foolery. The Professor of Divinity chewed his bacon collops, and did not speak; but when Kenelm used the word ‘resurrection’, he stopped chewing momentarily, showing a face that was highly discouraging.

None of the other professors would sit by Sir Kenelm, as they had developed a prejudice against him for the pungent smell about the east side of the college, caused by his experiments with crayfish. This was the first reason that they kept their distance. The second reason was the common belief that he had murdered his wife. These two offences combined extremely effectively, even in the mind of the Professor of Logic.

Most mornings, Sir Kenelm sat with Mary Tree, reading aloud from Discorides’ book of medicine, while Mary Tree followed another copy with her eyes. Since he had no books now, he had been obliged to borrow both of them from fellow Greshamites. He handled the book he read from carefully, as if it were the first he had ever seen, and he spoke slowly, taking care to see that she had the right place, so that with time she would be able to read for herself, he hoped.

Later, while the morning sun was still golden, Mary Tree went down to the banks of the Fleet where Sir Kenelm sent her looking for nettles, cuckoo-flower or sweet william. ‘They must be fresh and fair, for my purpose,’ he told her. ‘Both buds and flowers withal.’ She carried with her a basket and wore Sir Kenelm’s hawking gloves.

Kenelm sat cross-legged before the fire, meditating upon the meaning of ‘metempsychosis’.

At noon, Mary Tree spent an hour in conversation with Chater when he came to Gresham to get his washing done and collect his stipend. She perceived instantly, by his walk, by the sit of his hat, by the cast of his eyes, that he was a Catholic, though he wore no illicit garments. But she was not afraid to talk to him, nor he to her, it seemed. He was the type who found her Mark more fascinating than repellent, she supposed, and he hung about her as she performed her tasks, looking moody and uninterested but, as she perceived, taking solace from their conversation, which was necessary for his uneasy soul. Although Mary Tree was loath to show too much prurient interest in talking about Venetia . . .

‘Ommmm . . .’ said Kenelm, meditating. ‘Pherecydes of Syros taught Pythagoras who taught Plato that souls migrate, by metempsychosis, into other bodies. Orpheus turned into a swan; Thamyrias a nightingale; tame beasts were reborn as wild creatures, and musical birds in the bodies of men . . .’

. . . Chater wished to talk of nothing else: Venetia’s illness, how he had tended her, and his fears for her, which were rebuffed by her constant affirmation that she was perfectly well. Mary Tree expected him to talk of how dignified and gentle she was, and how she gave to charity, but none of these topics seemed to move Chater; he did not expound on her sweet nature.

‘Oh, to make her wait was foolish, such impatience she had!’ he said. ‘Sometimes she was taken by choleric moods, when she would suffer to have no one with her but her Chater.’ His lower lip was beginning to quaver with fond remembrance. ‘In those moods she could put lightning up me just by looking.’ Tears were welling in the undersills of his eye. ‘I would jump to serve her, and she would tolerate me only, letting me know of my foolishness with the tilt of an eyebrow.’

‘She was so unkind?’ asked Mary Tree.

‘She was so magnificent,’ said Chater. ‘Such a one as her leaves this life’s little stage empty. She had a mirror placed high in the alcove of her withdrawing salon,’ he said almost to himself, smiling.

‘So she could regard herself secretly?’ said Mary Tree, who thought she was beginning to understand Venetia’s character.

‘Ha! No, not for such seeming shallowness. She was not vain, you understand. She merely had splendour to maintain. No, she fixed the mirror there because she used it to secretly view the cards her friends held, I fancy. Winning was everything to her. To take money from other gamblers – this was her best delight.’

Mary pondered this. ‘Even from her friends?’

‘Oh, more from her friends than anyone.’

That these words came from a priest made them even more confounding.

‘She loved Sir Kenelm?’

‘Oh, unto death. She thought he was growing maggot-brained, and she used to say she despaired of him, and she thought no one else would have him, except her. When he went away she declined like a plant without the light. She would rather go hungry than appear before Sir Kenelm without her face painted and her eyes coloured, except when she was in the mood for candour, when they would spend all day at home together in their bedchamber . . . I brought them sweet sack and figs and books. I was their trusted one.’

When he spoke of her illness, Chater referred darkly to ‘the drink incarnadine’ or ‘the ruby wine’. He never said that this drink was to blame for her death, and yet he came always to the brink of saying this, and would then go no further, switching instead to the theme of his loyalty to Sir Kenelm, and asking moon-eyed questions about Sir Kenelm’s health and vigour, and once even enquiring if the shape of his calf held up, which was a question Mary could not answer.

‘Ommmm . . . We must all be reborn, says Plato, because there are a fixed number of souls, and many bodies constantly being born, so each soul must play its part again, and again . . .’

It seemed to Mary Tree, as she banked Sir Kenelm’s fire, while he sat muttering in front of it, that no one would have any peace until they had a better understanding of why Venetia had died, but then Mary had to go and put the ashes out by the kitchen garden, and service the water butt, and clean the swilling-house floor, before it was time to turn the maslin bread, and at last, to sit silently at the servants’ table. Here, she discerned that the others, in imitation of their professors, held away from her, putting up a discreet barrier of indifference, as if she, too, smelled of crayfishes and slander.

When she made Kenelm’s bed, Mary was frightened by a cold hand which she clasped under the pillow. It was so heavy it felt as if it were drawing her down, and made her start, but she quickly realised that it was a bronze made from a cast taken of Venetia’s hand, and Mary understood why Kenelm would wish to hold it close to him. She propped it up on the counterpane, but it looked amiss, almost as if it were waving, so she tucked it under his pillow again.

‘Ommm . . .’ His concentration slipped, and . . . Ping! Celestial spam arrived in the brain of Sir Kenelm.

‘Private cord blood storage facility – insure the future health of your loved ones by preserving their precious stem cells.’

Sir Kenelm accepted this enticing premise. ‘Umbilical cord blood and tissue is one of the richest sources of stem cells in the body with even better regenerative potential than bone marrow . . . We use cryo-preservatives, which are easy to remove post-thawing. Storage facilities are monitored with twenty-four-hour security. From £2,000 with additional phlebotomy costs.’

The Buckinghamshire radio mast was becoming less discriminating in the messages it sent to him. Previously it had blocked requests for money.

‘Cord blood can be used for treating: juvenile chronic leukaemia, Diamond-Blackfan anaemia, Neuroblastoma, Sudden Death Syndrome, autoimmune disorders including Omenn’s disease . . .’

Too late, too late, sighed Kenelm, and the message disappeared. He could feel himself becoming, for the first time in his life, self-involved, greedy in his thinking, when he should be disinterestedly intellectual. Grief seemed to have taken away all his strength. At least he was doing one pure, unmotivated thing, besides working on his project of palingenesis. He was teaching Mary Tree how to read.

Mistress Elizabeth came to Gresham College to deliver a basket of Kenelm’s bedding and sundries. After the dissolution of the Digby household she was expected to go and live with the boys and Mary Mulsho on the Gayhurst estate, but it emerged, to everyone’s surprise, that she had a husband in service with another recusant family in the city, and she was setting up house with him instead.

Mary Tree took the opportunity to question Mistress Elizabeth about Venetia’s possessions and the contents of her closet when she died. Elizabeth responded with guarded hostility, thinking this wench wanted a garter, or an under-garment, or a scrap of lace or tiffany for a talking point. And so she kept her counsel, and told Mary Tree nothing.

When Mistress Elizabeth had gone, Mary discovered, at the bottom of the basket, a pair of lady’s silver slippers, very finely made, with short heels and marks where chopines or pattens had once been attached. Mary sat a little straighter as she held them, as if they had rebuked her for her impropriety, and yet she also wanted to hold on to them, like treasure, as they gleamed. When Sir Kenelm came in he looked at them absently, and took them into his hands with ceremony, as if to say they were now in his safekeeping, and as Mary crept away, she thought she overheard him saying ‘in case she has need of them again’.

‘Palingenesis,’ said Kenelm, over a spoonful of potage, ‘from the Greek, palin, again, and genesis, birth, means the re-birth, revival, resuscitation or regeneration of living persons from their ashes or putrefying matter . . .’

‘’Tis more effective to make anew,’ muttered the Professor of Geometry, ‘which is why Talus the Iron Groom in Spenser’s book is germane to the purpose, being composed of an un-compostable ferrous material, which is to say, in a word—’

The Professor of Divinity broke in: ‘I thought “palingenesis” referred more usually to the conjuror’s impostorous practice of creating a miniature castle, flower or other such vain fancy out of ashes, for the amusement of a vulgar crowd. In my ignorance I was not aware that it had been practised upon persons living, or dead.’

Sir Kenelm did not notice the professor’s withering tone of voice. ‘Aye, there’s the rub, sir,’ he replied enthusiastically. ‘Not yet, not yet! It is not practised, but it exists in the minds of men already, as a word, an idea, an ideal and a dream, and as we know that truth and fiction are so intimately connected that Galileo calls his astronomy a fiction—’

‘Iron,’ continued Geometry. ‘Iron will, and no discernment, this is what makes an Iron Groom. He is in truth a weapon that walks about upright, composed of armour and clockwork. Armies of Iron Grooms would spare a nation in the wars . . .’

‘Then Spenser’s verses brings ideas to birth also,’ said Kenelm. ‘Make him, sir. Make the Iron Groom. Bring him to being. For as we dream, so we ought to do.’

‘Now I consider it, the phoenix rises from the ashes,’ said the Professor of Divinity. ‘It is no work of man to bring this about, though. It is heresy to attempt it.’

‘Try, try, try, and let them try me,’ said Kenelm. ‘La.’

The others ignored him, being busy looking into their own thoughts and pottingers.

Mary Tree having the duty of cleaning Sir Kenelm’s belongings, it was natural that she should find among them various relics of Venetia, including a box containing cosmetic pots and other feminine impedimenta, which she dared to suppose were the contents of Venetia’s closet. For the first week she respectfully refused to look inside it, and for the second week she left it in a prominent place in his rooms, hoping Sir Kenelm would do that instead of her. By the third week, she decided to take the matter in hand.

Two gallypots of subliming calomel; a beaker of brandy; a few sticky vials stained red; private correspondence with a midwife; a large quantity of bloody face-bandages, hidden in a wash-bag; dried herbs that Mary Tree could not identify, though they made her sneeze; a wrapper bearing the wax seal of a fat viper, and a few words of commendation from an apothecary; an enamel box containing two milk teeth, thought to be young Kenelm’s; and a large quantity of millipedes in a jar, presumably waiting to be used in a beauty preparation.

Mary Tree did not know what to do with this intelligence, only that she must keep it in mind. As she fell asleep she ran over the letters and word-sounds Sir Kenelm was teaching her, and she recited this list over and over, laying the letters out in front of her eyes, which started to crawl before her as she fell asleep, and formed into snakes like the fat viper on the apothecary’s seal.

All around her, in their lamplit kingdoms, the Gresham professors followed their callings, the Astronomer using his mariner’s astrolabe to navigate stormy seas of cloud, and the Professor of Law poring by candlelight over his edicts and assizes. The Professor Without Portfolio, for his part, gazed for hours into the red glow of his furnace at the ashes of a mound of cow-parsley, willing them to revive.

When the night was at its darkest, and the ashes were cool, he put on his black overmantle and took, after the fashion of a Melancholy Man, solemn perambulations about the gardens of Gresham and beyond, walking in the figure of the circle and the square. He smelled the spirits of the earth, rising up as the ground exhaled its night vapours, and he wondered whether the world still turned or if it was all over now.

Moonlight picked out the veined cheeks of ivy leaves, and the willow tree’s hair fell finely as it turned its back to him. Sir Kenelm glided beyond the kitchen gardens, and he saw the stock pond wink at him, and the long white arms of the path rise to beckon him. He lay down on the wet grass and rested his face on the breast of the earth, and talked to the soil.

He did not convene with ghosts, but apparitions of men who had not yet been born. Pre-ghosts, proto-ghosts. Widowers with pink eyes and foreign clothes, heavy spectacles misted with tears. He could not understand their customs, or their style, or rank, but he recognised their suffering.

‘Have you found no cure for this, three, four hundred years hence?’

‘No cure, no cure,’ sighed the wind.

‘Some ease for the mind,’ drawled the earth. ‘Talking, talking.’

‘Shock therapy,’ lashed the tree.

‘But no ease for the soul,’ sang the wind.

‘Pills to take away the pain. Sleeping draughts for wakeful hours,’ groaned the willow.

‘No cure for loss,’ spat the wind.

‘This is love’s price,’ announced the bell of the church of St Margaret. Four in the morning.

Sir Kenelm lifted himself upon one elbow, into the pose of Melancholy Thoughtfulness. A pattern of grass-blades was indented on his cheek and he was numbed by cold, as he desired. He resembled the statuary upon his own tomb. He realised why he felt no fear of the darkness, nor of the spirits he encountered. He had become a ghost himself.

But as the dawn came, when he paced lightly back to his rooms across the quadrangle, his feet left prints upon the wet grass.

[Sir Kenelm’s words are in the following chapter taken verbatim from a transcript of his lecture made at Gresham College in 1665 to the embryonic Royal Society.]

THE LECTURE HALL at Gresham College was full of contained expectation, like a pot before the boil. This being the occasion of Kenelm’s first public address since the accident, it was the cause of much interest, some salacious, and a large and varied crowd assembled, each trying to wear a casual face. Alongside the usual Gresham lecture-goers, the earnest autodidacts and shrewd men of business, there were more dubious visitors, newsbook writers, and common tongue-wags, as well as idle moochers come in out of the cold. They sat mixed amongst Sir Kenelm’s coterie, his correspondents through the Invisible College, Sir John Scudamore, Samuel Hartlib and Endymion Porter, his hair flowing over his collar, and out of breath, coming in at the last. There was also a distinguished divine, sent to gather intelligence by Archbishop Laud, while at the back of the hall glowered a row of half a dozen Puritans with their high hats on and their arms folded.

Chater could not help staring at Endymion. His countenance was too tight about the eyes and jowls, which had been clipped and pinned. His nose seemed to have been worked over as an afterthought, and it was somewhat raw, as if grated. After feasting his curious eyes too long, Chater pretended to look away. Endymion tapped Chater on the shoulder, while Chater shrank like a guilty sea urchin. In a low voice, Endymion told him to keep his eyes to himself.

‘Or else take a closer look at what my surgeon has effected,’ said Endymion, leaning in towards Chater, his vein-shot eyes bulging as he raised his collar to show off a blood-blister, ‘to put right the ravages of cannonshot. I’ve been taken by pirates in the Channel oft enough on my service for the King, and now I’ll not be served with timid prying eyes, so look at me and take your fill, sir.’ Endymion sat down with heavy satisfaction.

Sir Kenelm came in walking slowly, an antic figure.

‘He [Sir Kenelm] lived like an Anchorite in a long grey coat accompanied by an English masty [mastiff] and his beard down to his middle.’

Finch Manuscripts, 1691

While Kenelm arranged his papers, his dog Asparagus settled under his chair. Kenelm surveyed the crowd. So many shunned him now. There was no Davenant, no Killigrew, no Cavendish, no Thomas Howard, no, not even James Howell, even though his life was once saved by practice of the Cure of Sympathy.

Kenelm started with a few droll asides, about the longness of the lecture and the shortness of life, to put everyone at their ease. He was thinner, and his hair was scarce, but he still had an easy and natural manner of speaking, a warmth that was almost entirely unforced. He enjoyed his own presence and his voice; he was made for broadcasting.

He started off with simple figures:

‘Seeds growing are not a perpetual miracle, though you could be excused for thinking so . . .’ He delivered to the audience a reassuring smile.

‘An ackhorne grows to a spread, vast oak. A single bean to a tall green tender plant . . . And after, death, which is an essential dissolution of the whole compound, must follow: the perfect calm of death.’

The lecture hall’s attention tightened like an archer’s bowstring.

‘Trees look dead during drought, till some rain do fall to cure them of their sickness,’ he said. ‘And then vegetables take a new green habit. Now, my spagyrick art tells me it is nothing else but a nitrous salt which is diluted in the water . . .’

‘Spagyrick?’ said one would-be inkhorn in the front row to another. ‘Alchemical,’ scrawled his friend on his parchment.

‘Salt,’ announced Kenelm, ‘is the food of the lungs and the nourishment of the spirit.’

He explained that just as the drought-dead tree revives with nitrous salt, so ‘if it were made proportionable to mens bodyes there is no doubt but it would work alike effect on them’.

The direction of this lecture was emerging. Its immortal preoccupation was attracting newcomers, and the back of the hall became crowded with more figures: the shadowy form of Sir Francis Bacon, dead seven years ago of a cold caught in the snow at Highgate while investigating the possibility of freezing bodies for their resurrection. Another figure came shuffling in: Old Parr, the Shropshire farm tenant brought to London by Aletheia and Thomas Howard because he was said to be 152 years of age, and who died shortly after his inspection by William Harvey, who declared that the cause of Old Parr’s death was his removal to London. Behind him peeped Mary Shelley, a teenager, 161 years unborn, clasping a notebook.

Sir Kenelm continued quietly, controlling his voice. ‘In a villa in Rome Cornelius Drebell made an experiment in which salt revived a plant – I saw the wonderful corporifying of it . . . Quercetanus, the famous physician of Henri IV, did the same with flowers – rose, tulip, clove-gilly flower. On first view, they were nothing but a heap of ashes. As soon as he held some gentle heate under any of them, presently there arose out of the ashes, the Idaea of a flower, and it would shoot up and spread abroad to the due height and just dimensions of such a flower.’

‘The Idaea of a flower?’ asked the autodidact.

‘That is,’ whispered his neighbour, ‘the Platonic ideal, or archetype. The flower in the mind of God.’

‘But whenever you withdraw heate from it, so would this flower sink down, little by little, till at length it would bury itself in its bed of ashes.’

Kenelm was talking loudly now, with glittering eyes. The urgency of his grief pulled him forwards, and the audience with him, into Dark Territory, where he groped for Science.

‘Athanasius Kircherus at Rome promised he had done it,’ said Sir Kenelm, ‘but no industry of mine could effect it.’ The audience wilted with disappointment. ‘Until . . .’ said Kenelm, reviving them with the word. ‘Until . . .’ He shuffled his papers, cleared his throat.

‘I calcined a good quantity of nettles – roots, stalks, leaves, flowers. In a word, the whole plant. With fair water I made a lye of these Ashes which I filtered from the insipide Earth. I exposed the Lye in the due season to have the frost congeal it. I performed the whole work in this very house where I have now the honour to discourse to you. I calcined them in the fair and large laboratory that I had erected under the lodgings of the Divinity Reader.’

The Divinity Reader, who was sitting in the front row, changed his expression so subtly it was almost impossible to discern the displeasure this had caused. Asparagus watched him with one eye.

‘And I exposed the Lye to congeale in the windows of my Library, among my lodgings at the end of your Great Gallery.’

Most of the audience assumed his library was richly furnished, but Mary Tree, peeping in at the back of the hall, knew how bare he was at heart.

‘And it is most true that when the water was congealed into ice, there appeared to be an abundance of Nettles. No greenness accompanied them. They were white. But otherwise, it is impossible for any painter to delineate a throng of Nettles more exactly. As soon as the water was melted, all these Ideall shapes vanished, but as soon as it was congealed again, they presently appeared afresh. And this game I had severall times with them, and brought Doctor Mayerne to see it, who I remember was as much delighted with it as myself. What reason this phoenomenon?’

‘He’s cracked!’ whispered one tongue-wag to another; the hall murmured with awe and disquietude. Sir Kenelm imagined this meant his audience had grasped the eternal repercussions of his experiment: palingenesis, revivification, transgenic cloning.

‘Good experimental practice,’ muttered an autodidact. ‘But to what infernal end?’

‘The essential substance of a plant is contained in his fixed salt. This will admit no change into another Nature; but will always be full of the qualities and vertues of the Plant it is derived from; but for the want of the volatile Armonicall and Sulphureall parts, it is deprived of colour. If all the essential parts could be preserved . . . I see no reason but at the reunion of them, the entire Plant might appear in its complete perfection. Were this not then a true palingenesis of the Originall Plant? I doubt it would not be so.

‘Then we come to Real palingenesis – as what I have done more than once upon cray-fishes . . .’ He smiled at the cameras, the live link-up with his laboratory.

‘Boyle them two hours in faire water. Keep this decoction, and put the crevisses [crayfishes] into a glasse-limbeck, and distill all the Liquor that will arise from them; which keep by itself. Then calcine the fishes in a reverbatory furnace, and extract their salt with your first decoction, which filter and then evaporate the humidity . . . In a few dayes you shall find little animals moving there, about the bigness of millet seeds. These you must feed with the bloud of an Oxe, till they be as big as pretty large buttons. You may bring them on to what bignesse you please.’

The back of the hall had become a Sergeant Pepper’s gallery of faces, Sir Walter Raleigh and Helen of Troy, Dr Dee and Marilyn Monroe and Guido Fawkes, and also your face, and the face of every other reader of this chapter, and the present author, wanting to see everything, but caught behind the crowd of long-dead figures, and busy imagining what was going on instead.

Sir Kenelm was in his stride: ‘All this leadeth me to speak something of the Resurrection of Humane bodyes—’

The puritans at the back of the hall took this as their cue to stand up and shout, each in turn:

‘Necromancer!’

‘Abominable Popist!’

‘This meddles in life and death!’

Zealots of many stripes, Ayatollahs and Popes and pro-life campaigners yelled:

‘Do ye not respect the sanctity of the grave?’

‘Where lies your dead wife?’

Asparagus barked at them, and Sir Kenelm tried to answer their questions one by one, facing down their protests with the bald strength of a man who has already been to his wits’ end and back, but Endymion Porter and Sir John Scudamore set about a scuffle with them, restraining one Puritan man and knocking another’s hat off. The Puritans continued shouting all the while, proclaiming that Judgement was nigh. Chater made a discreet and hasty exit on his own. The Gresham College porters soon came and bundled the Puritans out of the hall, and the audience of learned men and cavaliers were left in uproar, arguing over the innocence of the widower, and the insupportable nature of Puritans. Sir Kenelm remained in the midst of them, silenced. The cold draft of dissent blew through the hall; all the spirits in attendance were long departed.

Later that evening Mary Tree tended Kenelm like an invalid, so weakened was he by his lecture. As she took away his cups and plates, and watered the sick sunflower that crisped upon his windowshelf, she decided that until Venetia’s death was solved, he would never be able to heal himself, and moreover, until he cleared his name, he would never be easy.

‘Credulity mingled with precise observation in his wide-ranging, receptive mind . . . Some of his research made positive contributions to scientific progress.’

The Oxford Dictionary of National Biography, 2012

‘He was the very Pliny of his age for lying.’

Henry Stubbes (1605–1678)