“WOW! That tanker is going to sail right under us!” Vladimir rolled down the car window and stuck his head out to peer down into the waters of the Chesapeake Bay and the top deck of an enormous freighter.

Richard didn’t look. He hated crossing the Chesapeake Bay Bridge. They used to take a ferry to get to Maryland’s Eastern Shore and the Delaware beaches, but the bridge had opened two summers ago and now everyone used it instead. The bridge was four and a half miles long and nearly twenty stories high at its midpoint to allow big ships to pass under. It gave Richard the willies to look over the edge from that high up.

“Ooooo, I wanna see!” Ginny was sitting between the boys and clambered over Vladimir to poke her head out, too.

“All heads inside!” Don called from the driver’s seat. But he laughed as he said it. The family was on its way to Rehoboth Beach for Memorial Day weekend, and he was in a jovial mood. Abigail’s aunt had a summer cottage there and always lent it to them for the three-day weekend. It was the first time Don had been able to join them in years. Usually, Hoover had him doing some undisclosed task on those days.

Reluctantly, Ginny crawled back to the middle seat. “You know, Daddy, this is the third largest bridge in the world. The whole wide world! It’s just too exciting not to look.”

Vladimir chuckled. “You kill me, Gin.”

“Thanks, Vlad!” Ginny smiled up at him, charmed, like everyone seemed to be by him.

At this point, Richard had learned to squash whatever sudden pangs of jealousy he felt about Vladimir, given the double life he was leading with him. Vladimir had also been way cool when Richard fessed up to escorting Dottie to her sister’s debutante ball.

“No sweat, buddy boy,” he’d said. “She’s old news. We didn’t have anything in common, anyway. It wasn’t meant to be.”

Nor were Richard and Dottie.

Yes, the country-club ball had been as incredible a date as all his daydreams had promised. Dottie was beautiful, wearing another fancy sky-blue dress that accentuated her eyes and her increasingly womanly figure. The band was great. Richard stole his first sip of champagne. And he’d looked pretty darn swell in his rented tuxedo. His mom must have taken a gazillion photographs.

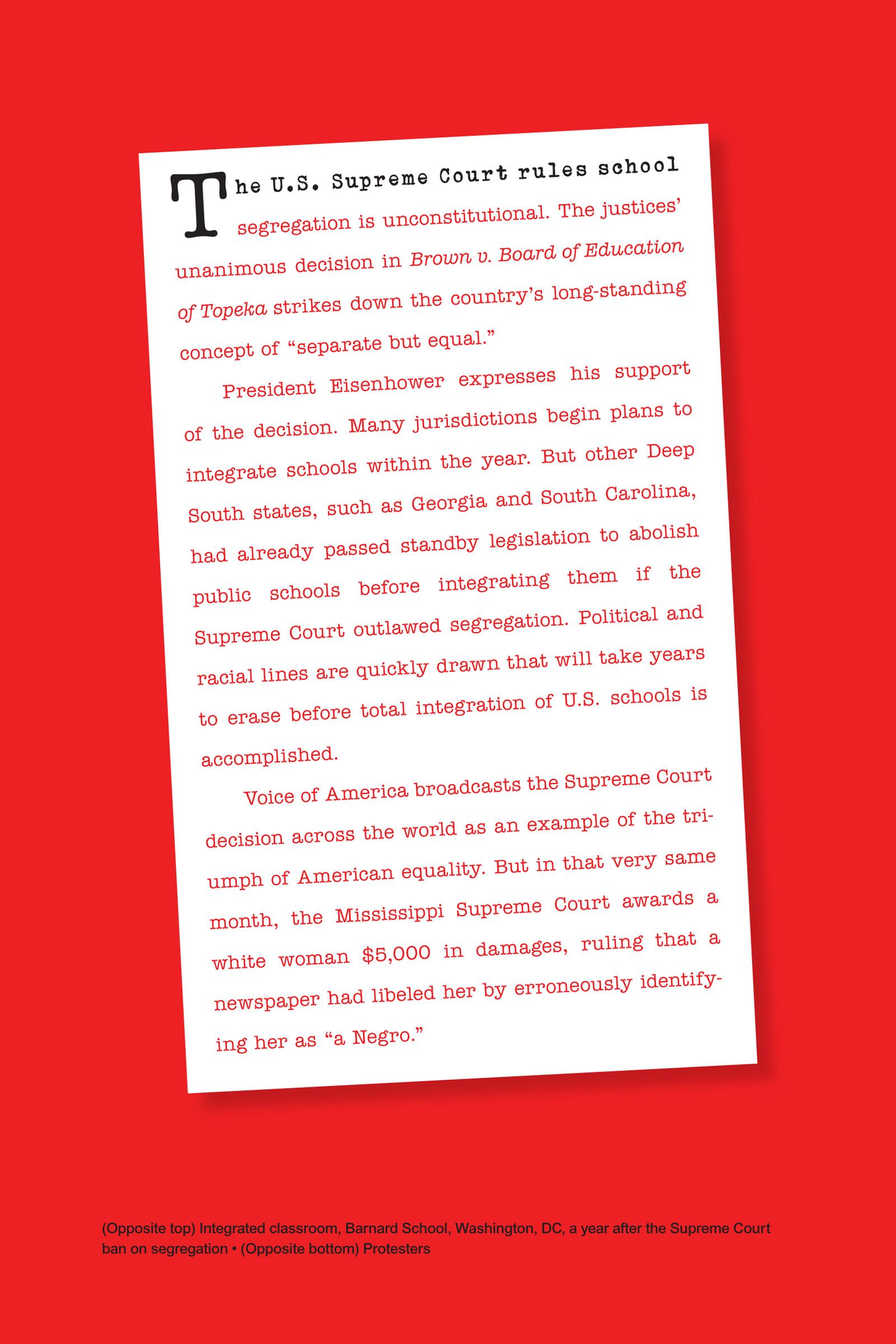

But Richard hadn’t really talked with Dottie since. She even managed to dart out of Biology class so fast when it was over that he couldn’t catch up to her. She was always surrounded by giggling girls, who suddenly turned serious and whispered behind their hands when they spotted him in the hallway. Right around the time the Supreme Court banned school segregation as unconstitutional, he was shocked to overhear one of the girls say something about his being best friends “with one of those n——lovers.”

So Richard wrote a song. About lost love. About insensitivity, humiliation, broken hearts. About love making a guy do things he knew were stupid. About popular girls stepping all over outsider boys’ souls.

I’m on the outside looking innnn,

Left broken and lonely from a heart made of tinnn.

Why she did it I’ll never knowww,

But Lord knows she left me feeling lowwww, so lowwww….

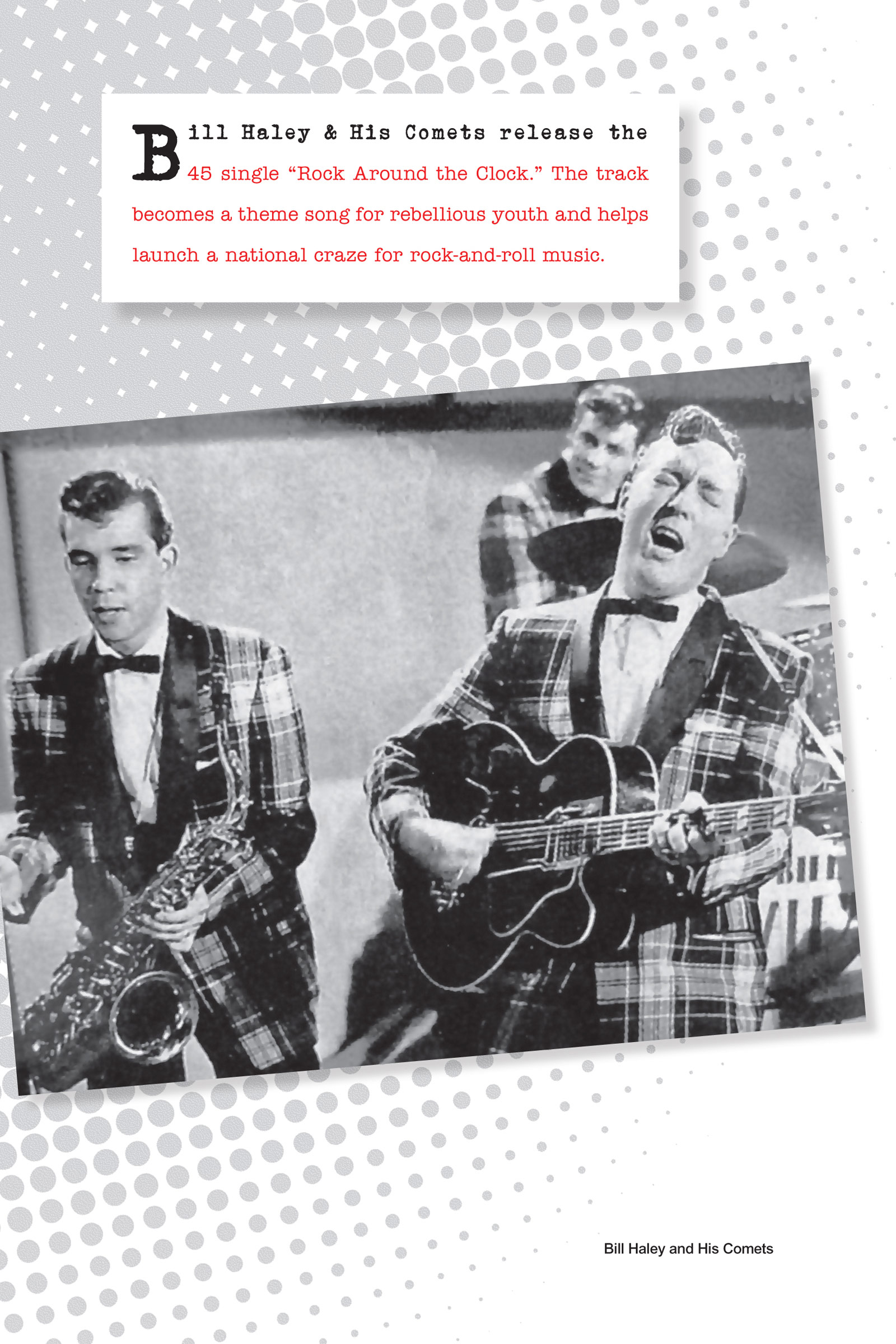

Vladimir was almost done composing a saxophone melody for it. What he played so far ached with hurt and longing, bitterness and hope, and a sense of resignation. The song would be a total tearjerker. Like that Billie Holiday song “Fine and Mellow.”

Richard had never heard of Billie Holiday before meeting Vladimir and Natalia. Now he was listening to her all the time, too.

Interrupting Richard’s thoughts, Vladimir said, “Hey, Mr. Bradley, thanks again for asking me to come this weekend. I really appreciate it. I haven’t been to a real beach for a while.”

“Sure, son. I know how tight you and Rich are. Besides, your being with us fleshes out the brotherhood, gives us a majority over the ladies.”

Everyone laughed.

Boy, Dad is in a good mood, thought Richard. He tried to assess Don’s expression from what he could see of his profile as Don glanced over his shoulder to talk to Vladimir. Was there a twinge of guilt in his face, too? Maybe inviting Vladimir was a way of making up for spying on his family. Or was it just Richard ladling his own discomfort onto his dad?

That night, they all went to the boardwalk. After hours of riding bumper cars, shooting water guns into the mouths of cardboard clowns, laughing at their distorted images in wacky mirrors, and eating weird-colored cotton candy and saltwater taffy, Ginny announced she’d had enough. She wanted to go home. She was reading The Lion, the Witch and the Wardrobe and had just gotten to the part where Edmund agrees to spy on his siblings for the White Witch in exchange for some Turkish Delight candy. “I’ve got to see what happens next. Can you believe? Agreeing to rat on his own brother and sisters and Mr. and Mrs. Beaver. For candy!”

Vladimir laughed. “Have you ever tasted Turkish Delight, Ginny? It’s a British favorite, with dates and nuts and jellies. It’s brilliant, it is, as my English mates would say. I can see it seriously tempting a guy’s soul. Legend says it is so delicious, it stopped a sultan’s wives from squabbling and brought peace to the palace!”

“Humph. Well, I wouldn’t spy on my friends and family for the enemy,” Ginny said steadfastly. “No matter what.”

Richard winced.

Abigail took Ginny’s hand. “Come on, sugarplum.” As they walked away swinging their clasped hands, Richard could hear his mother begin to explain that C. S. Lewis wrote Edmund’s temptation as a metaphor for the disciple Judas, who betrayed Christ for money.

“Oooooooohhhhhhh.” Ginny’s voice trailed off into the shadows of the dimly lit boardwalk.

Was it the cotton candy that made Richard want to vomit or his suddenly feeling a parallel to Judas?

“Okay, men.” Don clapped his hands together. “That’s a signal for us to take a walk on the beach and patrol for enemy subs!” He laughed at himself. “Seriously, let’s walk off that cotton candy glop. If we head toward the old World War II watchtowers, we’ll be away from all the surface light and have a great view of the stars.”

So Don, Richard, and Vladimir strolled to the boardwalk’s end. “It’s hard to imagine today,” he said as they walked, “but Nazi U-boats trolled along here, unchecked. Right out there. In fact, in the first months of 1942, right after Pearl Harbor, Nazi subs sank nearly four hundred American freighters and tankers off our Atlantic Coast, most between here and North Carolina’s Outer Banks. None of those old tubs were armed. The Nazis called it the Great American Turkey Shoot, the SOBs. Thousands of our guys died.”

They stepped onto the cool sand, and Don gazed out onto the dark waters.

“My uncle rejoined the Merchant Marine during the war to keep supplies going to England. Trucks. Guns. Food. Medicines. A lot of old geezers re-upped. Percentage-wise, the Merchant Marine suffered the highest casualty rate of any of the Armed Forces. And people never think about them.” Don stopped and did a salute toward the sea. “Thanks, Uncle Jack.”

They kept walking. For a long while, the only sound was the boom and fizz of waves slamming the beach, creating sudden shallow pools bubbling and sliding forward, then hissing sadly as they were sucked back into the ocean, making way for the next crash of surf.

When they were illuminated only by moonlight, Don announced, “This is perfect.” They flopped onto a dune. Don pointed toward the Atlantic: “There’s Sagittarius, the archer. See? That arc of stars that looks like a bow? Low on the horizon, just above the ocean.”

The boys nodded.

“Above us, that lopsided W, that’s Cassiopeia’s chair. And over there,” he said, pointing slightly inland, “is Cygnus. Look for a cross of stars that makes a stick body. Can you see what looks like a swan’s outstretched wings?”

Hushed, Vladimir and Richard looked to where he pointed. Gazing at the heavens was quieting the guilt Ginny had unwittingly poured on Richard. He barely breathed, worrying about distracting Don.

“Now sit real still and focus, boys. Stay on Cygnus. See that very faint swath of gray white around it?” Don held up his hand and swept it from left to right.

“Oh, yeah! I see it!” Vlad said quietly. He nudged Richard and pointed, and soon Richard found it, too.

“That’s the Milky Way. Keep an eye out. Don’t move and you’ll eventually see something bright skip across it. That’ll be a shooting star.”

Amazed by the unmistakable reverence in his dad’s voice, Richard glanced over and saw a quiet, peaceful smile on Don’s face.

“I didn’t know you knew so much about stars, Dad.”

“What?” Don frowned a little. “Yeah, I guess we haven’t had enough time for sitting and talking about stuff like this. That’s going to change, Rich.” He reached over and ruffled Richard’s hair without taking his eyes off the sky.

All three kept their gaze heavenward, chins up.

“Did you study astronomy in college, Mr. Bradley?”

“Nope. Political science and frat parties. Wish I’d been more of a reader, like you two.”

Vladimir elbowed Richard and gave him a wink that said Hear that?

Don laughed, noticing the gesture. “No, I learned about the stars during the war. On the way home from missions. The Brits flew night raids. We went in daylight. But sometimes, on our runs into Germany, we didn’t get back to our base in England until the sun was long set. After all that exploding flak, planes rupturing and going down, the cannon fire of the Messerschmitts chasing us, the flash-bang of ack-ack guns from below…” He trailed off for a moment and then almost whispered, “If we were lucky enough to make it back to it, there was a blessed darkness over the English Channel.”

He paused. In the gloom, Richard could see his father lift his hand as if brushing away a mosquito. But Richard wondered if it was a tear, if Don was thinking about his own plane rupturing and his capture and…

“Up front,” Don almost whispered, “the pilots could spot those bright white cliffs of Dover shining through the gloom. That’s what they flew toward like starved, thirsty men. For me, back in the tail, it was seeing the stars suddenly pop out, one after another, like angels showing up to tell me I was going to survive. I learned to pick out the constellations that took me closer and closer to base, to going home to Abby.”

Richard had never heard his dad talk like that before. He seemed so different.

“AHA!” Don pointed. “There! Did you see it?”

A razor-thin streak of golden fire.

“I did!” Richard cried.

“I did, too!” called Vladimir.

Don laughed. “Make a wish, boys.”

Richard’s was that the night would never end.

But, of course, it had to.

On the walk back, Vladimir darted away from Don and Richard, waving his arms wildly, to chase the zigzagging eddies rushing up the beach and then back toward their mother ocean. They laughed at his antics. Vladimir rarely acted so silly. Richard shook off the thought of how his friend’s unabashed glee would vanish if he knew that Don was spying on him. And that the surveillance was prompted by Richard’s ratting on Vlad’s family.

Richard didn’t want to think about it. The night was too wonderful for that. Instead, he said, “This is great, Dad.”

“That it is, Rich. Sure beats the heck out of what I’ve usually been doing over Memorial Day.”

At that moment, when his dad seemed so open, so at peace with himself, Richard dared ask, “What were you doing, Dad?”

Don drew in a sharp, deep breath. But he answered quietly: “Placing bets for Mr. Hoover at the horse races.”

“What?” Richard exclaimed, before he could edit himself.

Don looked over at Richard and smiled sheepishly. “He and the FBI’s number two man, Clyde Tolson, vacation in San Diego every year, enjoying box seats at its famous Del Mar racetrack. For free, I might add.

“But the director doesn’t want people knowing that he likes to wager on horses on a regular basis. Hell, betting is something McCarthy uses as evidence against people—claiming it makes them vulnerable to being blackmailed by commies into doing traitor’s work. Some federal workers lost their jobs because they like to lay down a few bucks on a race.”

Richard was stunned, listening. That was so…so…Dare he think it? So hypocritical.

Don seemed to read his mind. “There’s a lot of hooey in our government these days.”

He paused a moment and then continued, “But here’s the thing, Rich. There are people out there in the world who do hate America. Hate the way we live. Hate our freedoms, our individualism. A lot of Communists want to destroy democracy because they don’t understand it. They’ve been told it’s corrupt. They’ve been fed a lot of propaganda about capitalism and our supposed greed and evils. They have set up spies among us, and seduced or coerced some of our fellow Americans to betray us.”

Richard nodded to keep his dad talking. Thinking about Vladimir and what he may have done to his best friend’s family, he needed to hear this truth, this rationale, as much as Don seemed to need to say it.

“The Cold War is real,” Don continued. “The Soviets have the bomb. Communism is spreading. Now China is Red. North Korea. North Vietnam. The Cubans almost turned into a satellite for the Russkies a few months back—just one hundred miles from Key West! Communism is bad mojo. Look how viciously the Soviets put down the East Berliners who simply wanted to reunite with their neighbors.

“So I’m like those old merchant mariners. I know there are some serious holes in the boat, but there’s a job that needs doing against bad guys. Right now, it ain’t perfect, but the FBI is my best ship. Does that make sense?”

Richard couldn’t tell if Don’s question was really for him or not. But he answered anyway. “Yes, sir. That makes sense.”

Don studied Richard’s face for a moment, then shrugged off whatever he was thinking. “Anyway, going back to my placing bets for the director. The deal at the bureau is this: if you screw up a case, you’re on the outs with Mr. Hoover. You have to work your way back into his graces with stuff like placing bets for him. Running errands. Painting his house.

“But looks like there’ll be no more of that for me. That’s finally changed.”

Don put his arm over Richard’s shoulder, and the two of them stopped to watch Vladimir run up and back, up and back, laughing with the waves.

This, this kind of connection, this kind of conversation, seeing his dad calm, his sense of purpose restored, this was Richard’s Turkish Delight. He looked to the heavens for another falling star to sanctify his new wish—that it would all be worth selling out his best friend’s family.

The next day, Vladimir and Richard were lying on the beach as Ginny frolicked in the waves. Don had taken Abby out for lunch, saying he wanted a date with his sweetheart, and the boys were in charge of keeping watch over Ginny.

“I really like how much your dad still goes weak in the knees over your mom,” Vladimir said.

Richard laughed. “Yeah, but sometimes it’s embarrassing how gooey they get.”

“Better than the alternative, trust me.”

Richard looked at Vladimir with surprise. “Your parents get along.”

“Oh, sure. But it’s not the same. My dad is all about his job. And Mom—you wouldn’t notice it—she hides it well. But Mom is pretty haunted. I don’t think Dad gets it, and that kind of puts a distance between them.”

Richard propped himself up on his elbows. “Gee, I’m sorry, man. I had no idea. It doesn’t show at all.”

Vladimir’s answering smile was rueful. “Yeah, well, I see it on her face when she thinks no one’s looking. Like when she’s painting. Or when she listens to music by Dvořák or Janáček. Horrible things happened all around her when she was not that much older than we are. She lost a lot of friends and family to the Nazis. That kind of thing has to wreck your heart.”

Vladimir grabbed a handful of sand and let it drain like an hourglass. Richard had no idea what was appropriate for him to say. So he stayed silent, to let Vladimir speak again or to change the subject.

“To tell you the truth,” Vladimir went on, his voice low and serious, “I think sometimes she feels really weird about being the wife of a U.S. diplomat. First off, the Allies basically sold out her country in the Munich Pact and handed it over to Hitler. All to appease the SOB and avoid another fight. But the war happened anyway.”

Richard shifted uncomfortably. What Vladimir said was totally true. The Allies had betrayed the Czechs. His History teacher had talked about it.

“Mom has a lot of guilt about being able to escape Czechoslovakia as the Nazis marched in. She could get out because she was a U.S. diplomat’s wife. But she couldn’t take anyone else with her, other than me and Natalia. I think she feels like a traitor. To her family, anyway. Most everyone else she loved was trapped. One side of her family completely disappeared in concentration camps. Others died fighting in resistance groups.”

Richard cleared his throat. It was dry with discomfort. Americans didn’t talk about this kind of stuff. They might joke about how hard it was to get gasoline and shoes and sugar that were rationed during the war, but nothing about losing their entire family.

“Then”—Vladimir drew out the word before continuing—“in the final days of the war we let the Soviets ‘liberate’ Czechoslovakia and Eastern Europe. The Soviet occupation was just swapping one form of slavery for another. We just stood by with our hands in our pockets and let the commies take over. What little bit of family Mom has left is in terrible danger. Anybody who is pro-democracy or has some relative living in the West is.”

He sighed heavily. “That’s why she’s working so hard to find her cousin.”

“Who?”

“You know that guy she was arguing with up in New York?”

Richard sat up abruptly. “Yeah.”

“Remember the AP bureau chief the Czechs arrested a few years back and just released recently?”

Richard’s heart started beating loudly. He itched to tell his best friend about seeing the magazine article—that’s the kind of thing best friends shared and noodled out the riddles of together. Unless, of course, one friend was spying on the other. So he asked as nonchalantly as he could: “You mean the journalist who says he was tortured by the commies into confessing he was spying on them for us, when he really wasn’t?”

“That’s the one.”

Richard nodded. “Yeah, I remember. Dad told me Voice of America called him the first American martyr for freedom of the press behind the Iron Curtain.”

“Yup. That’s true.” Vladimir hesitated. “Maybe I shouldn’t talk about this. Mom’s got no love for that guy.” He looked over at Richard. “You won’t tell anybody?”

Richard felt his face flush. “No.”

“Swear?”

Richard swallowed hard. “Sure.” What a liar he had become.

“Well,” Vladimir began, “the journalist had three Czechs working for him—finding him sources and stories. Like one article about a coal mine strike in a small town about twenty miles outside Prague. A Communist government doesn’t want information like that getting out. All its workers are supposed to be happy!” Vladimir snorted in disgust.

“What’s this got to do with the guy your mom was yelling at in New York?”

Vladimir startled. “I shouldn’t be talking about this.”

Richard kicked himself. He needed to be patient, that’s how confessions worked in his detective novels. Just let Vladimir tell the story how he wanted to. Don’t ask questions, or he’d spook.

“Seriously, man”—Richard tried to soothe him—“I’m sorry for interrupting. I’m just really interested, that’s all.”

“Well, you should be. It’s real 007 stuff.” Vladimir fell silent, staring at the ocean. But after a long pause, he spoke again, obviously worried about Teresa and proud of her, too. “Mom’s cousin was one of the Czechs helping the American journalist report stories. Right before the AP bureau chief was arrested, her cousin was dragged off by the Státní bezpečnost, the StB, the Czech secret police.”

Richard nodded. He’d gotten that man’s arrest story from snooping into the article on Teresa’s desk.

“The journalist’s trial was anti-Western propaganda all the way.” Vladimir grew agitated as he talked. “The charges against him were totally trumped up to convince Czechs to hate the United States, to make it seem like we’re sending saboteurs in to undermine their country. And to scare the bejeebees out of anyone thinking of leaking information to American reporters.

“During his trial, the journalist confirmed that Mom’s cousin worked for AP. My dad and I think the journalist just didn’t realize what his confession would allow the commies to do to his Czech employees. Mom’s cousin was sentenced to twenty years. Twenty! He didn’t even get a chance to defend himself.”

“Geez Louise,” Richard murmured. It wasn’t fair to blame the AP chief, but he could see why Teresa had drawn horns on his photo, given her perspective.

“I only met her cousin a couple of times when we were in Prague after the war and before the Communist coup six years ago. But I remember his playing charades one Christmas. He gave me that hand-carved marionette that’s hanging in my bedroom.” He shook his head. “He was a real nice man, very idealistic. I remember that.”

“So, what will happen to him?” Richard was beginning to feel queasy. This story wasn’t matching his interpretation of the stuff on Teresa’s desk at all.

“No one can survive twenty years in a Czech prison. Mom’s found out that he’s being held in Ruzyně, a hellhole just outside Prague. She’s trying to get him out. Find some official or guard she can bribe. She has a childhood friend who fled Czechoslovakia during the coup and made it to Paris. But he still manages to slip back and forth, smuggling people out. He’s even got the chutzpah to carry radio transmitters in so Czechoslovakians can hear Voice of America broadcasts. He’s trying to get whatever information he can about her cousin.”

The refugee doing “mysterious errands” in the article. It had to be. Richard felt himself begin to tremble with misgivings.

“And if that doesn’t work,” Vladimir continued, “her backup plan is to try to sweet-talk the wives of the Czech Embassy here into asking their husbands to help. Those guys are all big-time operators in Czechoslovakia’s Communist Party or they wouldn’t be trusted enough to be sent to Washington. That’s why Mom plays cards with those women. I swear I hear her vomiting in the bathroom every time she comes back from seeing them.”

Richard’s head was spinning. Suddenly, all those maps and clips and letters on Teresa’s drawing table made sense. She wasn’t a Red. She wasn’t a pinko. Even with all her artsy, crazy, left-wing ideas. She was the exact opposite!

Oh God. What have I done?

“Hey, Rich?”

“Yeah?”

“Where’s Gin?”

Richard looked toward the ocean. For the last half hour, Ginny had been right in front of them, jumping up and down, splashing, up to her knees in calmer water, a few yards inland from the breaking surf. He’d checked that she was still there a few minutes before. But now she wasn’t.

He scanned the beach to the right, to the left, looking for her red, white, and blue polka-dot swimsuit and the conical Japanese straw hat she’d gotten at the cherry blossom festival. Children digging, mothers scolding, teenagers roasting. No Ginny.

Richard stood, feeling the slightest shadow of panic. He looked back toward the house. Maybe she needed the bathroom? No. No recent wet footprints heading that way, either.

Shading his eyes, Richard looked more closely at the water. A couple of people were floating, treading water just beyond the cresting waves.

“Would she have gone out beyond the break line?” Vladimir asked.

“Maybe. She’s pretty gutsy.” But she sure shouldn’t be. Ginny wasn’t that strong of a swimmer yet.

He jogged toward the water, watching the floaters. The sun was so bright, the water glinted and glimmered, blinding him. He couldn’t make out their faces. One of them had to be Ginny, though.

But just as Richard waded in up to his thighs and cupped his hands to shout for her, a woman several yards down cried out and fell up to her neck, sliding several feet toward the crashing waves until her husband grabbed her.

“Oh, my,” she spluttered, as he righted her. “That undertow is horrible today. It just yanked me off my feet.”

Undertow! Richard’s heart sank. “Ginny!” he shouted. “GIN-NY!!”

He watched for a response from the floaters as he scrambled into the cold water. Nothing. He dove in and started swimming out to them, holding his head above water so he could see, when he heard Vladimir calling.

“Rich!”

He turned, kicking to keep himself afloat. Vladimir was pointing frantically past Richard. “She’s behind you!”

Richard turned around just as a wave crested and crashed down on blond curls and flailing arms.

“GIN-NY!”

Dark swirling water surged over him, crushing all the air out of his chest. Richard came up coughing. “GIN-NY!”

He lunged through the water to where she had been. He whipped himself around, searching. There! Just above blue-ink waters—her upturned face. Thank God, her eyes were open. He could see her gasping for breath.

“GINNY! Swim to me.”

He almost cried when he saw how frightened she was. “Rich!” she squeaked.

He pulled himself toward her, kicking and stroking the cold water as hard as he could. Almost there. Almost. Just a few more feet.

Another wave was coming. It would beat him to her.

“GINNY! HOLD YOUR BREATH! GO UNDERNEATH THE BREAKERS!”

How enormous the wave seemed. It crashed and pushed Richard below the angry surface where the competing currents—in, out—tumbled him over and over. He forced his eyes open against the sting of salt to look for gray water, the surface illuminated. He crawled his way up, to the sun, and bobbed up to air, gulping it in desperately like a dying fish.

But no Ginny.

“GIN-NY!!!”

The ocean whipped his legs backward and forward as the tide shoved in and the undertow rushed out, suspending him in a watery push-pull argument. He felt a slap of warmer water streaming out to sea and then what felt like a fish slide along his leg.

Richard would never know what made him do it. He reached down and grabbed it. It was Ginny. Ginny’s arm.

He dragged her up, coughing, vomiting water. But alive.

Richard didn’t fight the next wave. He just clung to his little sister to hold her up and let it crash and carry them like leaves skimming along a stream to the shore. Vladimir met them in neck-high water and half carried them both out.

Shivering, crying in relief, Richard and Ginny sat on the sand, gasping for air. Richard wouldn’t let go of Ginny’s hand. Her legs were all scraped up from being dragged by the undertow along crushed shells and pebbles, her lips were blue from the cold waters, and her hair was matted with sand. But she was alive.

Vladimir quickly wrapped her in their beach towels, as Ginny leaned her head against Richard’s shoulder. She smiled weakly. “Well, that will make a great first story for an inquiring camera girl.” She looked up into his face. “Don’t you think?”

The boys gaped at her.

Finally, Richard choked out, “You kill me, Ginny.”

“Almost literally,” Vladimir added.

The three half laughed, half sobbed, baking back to life in the sunshine.

On the drive home from the beach, Ginny stayed tucked up against Richard’s side. She dozed most of the three hours and was peacefully sound asleep when they pulled into Vladimir’s driveway.

Don whispered to Abigail, “I’m going to walk Vladimir in. I want to tell his parents how grateful we are for his part in saving Ginny.”

She nodded.

Vladimir and Richard grinned and waved a silent good-bye to each other.

Don stayed at their front door for a long time, talking to Vladimir’s father. When he came back to the car, his jovial weekend attitude, the gratitude for his daughter’s life that had lit up his face all day, was gone. He looked ashen.

“What’s wrong?” Abigail whispered.

“The State Department has suspended Vladimir’s father, pending a Loyalty Review Board hearing. He’s been identified as a possible security risk.” Don rubbed his hand along his forehead. “It’s because of Teresa. She’s friends with people on FBI watch lists, with radical writers and artists. She communicates with Communists in Prague and socializes with Communists here at the Czech Embassy.

“It’s possible he could be called in by McCarthy to testify, as well. He’ll lose his job for sure if that happens.”

In the backseat, Richard felt like he was drowning all over again. He couldn’t breathe. This was his fault.

“Dad,” he gasped. “They’ve got it all wrong.”

“I don’t think so, son. They…We’ve got a lot…” He paused and looked at Richard in the rearview mirror. “A lot of…evidence.”

“We?” Abigail asked.

“The FBI. We’ve had surveillance on her for a while.” He and Richard locked eyes in the mirror. “We received a solid tip-off that she might be Red.”

“Oh dear,” Abigail murmured.

“But, Dad, it’s…it’s all a mistake.” As quickly as he could, Richard spilled out what Vladimir had told him.

Don winced, looked down, and shook his head slowly, over and over. When he finally lifted his face again and looked up at Richard in the mirror, his eyes were full of rage. Like he’d just figured out that he’d been duped or something. And his hands were shaking so badly, Abigail had to turn the key in the ignition for him.