CHAPTER SIXTEEN

VALLEY OF THE SHADOW OF DEATH

After ten nights, we marched into a fairly good-size town wedged in a valley between the Kangnam and Pinantok mountain ranges. I heard the guards talking and finally figured out that the town’s name was Pyoktong. It was early morning and a thick fog covered the tops of the mountains. As we approached, I could see numerous small streams cutting through the valley. A patchwork of turnip and corn fields spread around the outskirts and a few cattle mingled in a pasture. The cows were small and I could see their ribs.

The guards marched us to houses that lined the road. I’d just sat down on the dirt floor of one when I heard the hum of aircraft above.

“Americans, Americans!” I heard someone yell.

The hum changed into a screech as the planes started to dive toward the road. Everyone began to panic, even the guards. The buzzing of machine guns cut through the screech. Rounds started to rake the road and blast through the thin walls of the house. It sounded like a sharp pencil popping through paper. One of the prisoners in my house understood Korean. He was from Hawaii and also spoke Japanese, which many of the guards spoke as well.

“Let’s take off,” he heard one of the guards say.

“What about the prisoners?” another guard said.

“Screw the prisoners, let’s go.”

The guards outside of our house took off up the hill on the other side of the road.

We threw open the doors and followed. I looked down the road and saw all the prisoners pouring out of the houses. Searching the skies, I saw the glint of the aircraft turning around for another pass. We climbed up the hill as fast as possible, clawing at the dirt as the planes peppered the village again. As we reached the top, I heard a series of explosions below. The Air Force hit an ammunition storage area, and multiple explosions echoed across the mountains. All the prisoners were cheering and hollering.

“Hit the bastards again,” someone yelled.

Thick black smoke curled up into the sky as the houses burned. I watched the planes climb high into the sky and disappear behind the clouds. Looking back at the town, I could see the bodies of a few prisoners near the houses. Others were wounded.

Numerous Korean soldiers started rounding up the rest of the prisoners. In the confusion, three of us slipped over the hill. We huddled together in a ditch, covering our hiding place with branches. We hoped to wait until nightfall and try to move back toward our lines. As we huddled together to keep warm, we talked about our chances of getting back .

“Any idea which way our lines are?” asked one guy. I’d never seen the other two soldiers. It didn’t matter. We were all prisoners with one goal.

The other soldier and I shook our heads no. I sat back in the ditch and tried to get my bearings. It was hard because we had moved in during the night and the mountains now seemed to wall us into the valley.

“Well, we came from that direction,” I said, pointing up the road that seemed to turn south. “I guess we could start that way and try to get over the mountains. We can use the road as a guide, but we will need to stay off it. All we need to do is keep moving south.”

The older-looking guy with a healthy beard just shook his head.

“Suicide in our condition,” he said. “We won’t make it over those mountains. We don’t have warm clothes and we will probably die of hypothermia.”

We knew he was right. It was smarter to wait until springtime. We needed to try to survive and hope our forces liberated us. A few minutes later, a Korean patrol spotted us in the ditch. None of us ran. We were all too cold and knew there was no place to go. The guards started to yell at us and quickly surrounded the ditch.

As they thrusted their bayonets at us, one guard gestured for us to stand up. We stood, and he pointed back over the hill. They pushed us around a little as we climbed out of the ditch. When we got to the other side, we saw the rest of the prisoners together in a tight group. The excitement of the air raid was long since over, and now everyone’s interest was in trying to keep from freezing.

The North Koreans seemed reluctant to take us back to the huts, so we huddled on the hill and suffered another frigid night. From above, our mass of men probably looked like a giant blob having a seizure. This time, we didn’t have the cornstalks to keep us warm. We tried our best to stay huddled together, but the cold from the ground easily seeped into our bodies. I couldn’t stop my teeth from chattering and barely slept. It wasn’t until I was so cold that I couldn’t feel my hands and feet that I finally got some sleep.

At dawn, they marched us down the road. But instead of back into town, we headed south. It was obvious they had no idea what to do with us. After hours of shuffling down the road, with one eye hoping to see the glint of more Air Force fighters, we stopped at a village. I figured we couldn’t have marched more than a dozen miles from Pyoktong. The village sat deep in another valley. There were small farms of one or two houses stretching all the way up the valley for approximately two and a half miles. A small stream ran alongside of the road. It was completely frozen over.

As we moved up the valley, the Koreans started randomly splitting us up in groups and placing us in the houses. The guards crammed about twenty men per room in each house. Each farm appeared to have been one family’s home.

The houses were made from wooden poles, with mud-baked walls and thatched roofs. Each house had three rooms, two bedrooms and a kitchen. The doors were covered only with paper and offered very little insulation or warmth.

It looked like the families that owned the houses had left in a hurry. Some of the farm tools were still there in open lean-to sheds beside bins of corncobs. Doors to the houses had been left open. Clothes, missed by the families as they hastily packed, littered the floor. I was placed in the last farmhouse. There was one other house beyond us, at the highest point in the valley, where the officers were held.

The valley was deep and the sun was only visible for three hours a day before it dipped too low on the horizon to warm the land. Temperatures hovered at freezing most days and dipped well below at night.

I got stuck sleeping near the paper-covered sliding doors. It was the coldest place in the room. One side of my body was always freezing. We were packed so tightly into the rooms that everyone had to move in unison. I was always happy when the decision was made to roll over.

The next morning five North Koreans crashed into our house. They threw open the sliding doors in both bedrooms and rousted us out. The leader, a stocky English-speaking officer with a clipboard in hand, started asking for our names and ranks. As we answered, they checked us off and moved on. When they got to me, the officer told me to come with him. I had no idea why. Did they know that I’d tried to escape twice already?

“You in charge,” he said. “Everyone must stay in this area.”

He indicated by pointing.

“You can go get water there,” pointing to a nearby stream. “You understand?”

I nodded my head yes.

“Go inside,” he barked. The rest of the group went back into the house, but I stayed.

“When are we going to eat?” I asked.

“Soon,” he said.

The millet, which the guards brought to us twice a day, was running right through us. There was absolutely no nutritional value in it and no seasoning whatsoever. Everyone was losing weight. We were all beginning to look like scarecrows, some like walking death. Four or five men were still eating out of one helmet liner. Everyone was watching the other guy to make sure he did not get more than his share. We were slowly being reduced to the level of animals.

“We need medical care. We have men that are wounded and sick.”

He said nothing.

“We need blankets and heat.”

He looked up from his clipboard and gestured for me to go into the house.

“Go, go, go now.”

I never saw that officer again. Our complaints and needs had fallen on deaf ears once again. I went back inside and tried to organize the men. I knew the North Koreans weren’t going to take care of us. Sergeant Martin was the next highest ranked soldier in the house. I pulled him aside and told him he was responsible for the soldiers in the second room and I’d take care of those in the first room. I’d never seen Martin before. We didn’t bother with first names or backgrounds. At this point, he and I were focused on living another day. I knew he was in my same situation, and that was good enough for me.

My goal was to bring back discipline and start acting like soldiers again. The scene the first night with the rice dropped on the ground was burned into my brain. The only way we could survive until spring and a possible escape attempt was to start working together.

“I asked the officer for food and blankets,” I told Martin. “It remains to be seen if we get anything from him.”

We walked out to the stream near the house. It was covered in a sheet of ice. Near the bank was a three-foot-deep hole where the Koreans got their water.

“Get a detail together and start getting water to the men,” I said. “We can carry the water in the helmet liners.”

Soon, three men were on the bank. Two of the men held the other by the legs while he went headfirst into the hole like a bucket in a well. Seconds later they pulled him up with a helmet liner filled with frigid water. I hoped the cold took care of the germs. I knew one thing: I didn’t want to be here in the spring after hundreds of men had been defecating all over the place.

The Koreans took ten of us out under guard and moved us up the valley, where they told us to collect some firewood. We took the wood back to the house and the guards made us break it down into five piles, one to heat the house each night.

The house had hard dirt floors, and underneath was a small tunnel system that ran from the kitchen. Normally the family cooking in the kitchen would heat the floor of the house, but since we weren’t cooking, no heat. That night, we took a pile of wood and started a fire in the tunnel. The heat in the floor only lasted half the night, but it still felt great. The lice loved it too. As I scratched, I thought of an old joke.

A guy goes to the doctor.

“I’ve got crabs.”

The doc asks him if he has a lot of crabs.

“Well I’ve either got a lot or one on a motorcycle.”

The sick and wounded suffered the most. Our frostbitten feet had turned to trench foot, and open wounds were infected or gangrene had set in. For those guys, it was only a matter of time before they died, since we had no medicine to treat them. I saw some of the soldiers turn to home remedies or even voodoo to treat their wounds. One guy took burned wood, scraped the charred area into powder form and swallowed it, thinking it might help stop or slow down the dysentery. Another one thought putting pine sap or turpentine on wounds would help heal them.

I tried none of it. I tried to clean my wounds every day. They were doing remarkably well considering I had no medication or bandages. I was keeping them as clean as I could. The shrapnel across my lower back was my biggest problem. I couldn’t see it. I could only feel the shards and they were aggravated by the waist of my pants. But I was a lucky one. I healed quickly and none of my wounds got infected.

A couple of guys in the house were already sick. All of them were running a fever. Others, like a guy named Graves from Philadelphia, were bordering on pneumonia. He was nineteen years old and had just graduated from high school. Without any medicine, the only thing left was to feed his mind with good thoughts. My only hope was that if he stayed positive his body could fight off the infection.

We talked about all things Philly. We talked about meals at Bookbinders seafood restaurant. Everyone from Philly knows Bookbinders. A city landmark, in the 1950s it was known for its five-pound lobsters and for being a place to see celebrities and sports stars. We talked over and over again about the lobsters’ orange-skin shells. We talked about what we’d eat. What we’d drink. At times, I could almost smell the food.

If we weren’t at Bookbinders, it was a block party. The police would close off one whole block and partygoers, bands, games, food and rides were set up. As with the restaurant, the memories were driven by our lack of food. Over the next month or so I repeatedly smelled the food, until I could taste what I was thinking about. We soon realized we were torturing ourselves.

As the days passed, he got worse until finally he stopped eating. I talked to him about his mother. I pleaded with him to eat so that he could leave when the American troops got to us. Anything to give him the will to keep going. Soon, he became delirious from fever and no food. He talked to his mother like she was in the room. He wailed at night. This spooked some of the guys. I saw a few lie with their hands over their ears.

Two nights later he died in his sleep. We took the body behind the house and dug a shallow grave. There were four of us in the burial party, and a man from South Carolina said a few words. We closed the grave and filed back inside. Everyone was silent. Graves was the first to die. Seven from our two rooms would soon follow him.

The valley had turned into one of death and suffering.

Soon after Graves’s death, Chaplain Kapaun came to the house. We were all surprised to see him. I had last seen him at Unsan, but when he walked in I barely recognized him. The man I’d met on a ridge in Pusan was gone. He’d lost a lot of weight and his uniform kind of hung on his frame. His tired and worn-out eyes belied his warm smile.

“Where are you staying?”

“I’m staying with the officers in the house at the top of the valley,” Kapaun said. “Dr. Anderson is also there and he is trying to get the Koreans to allow him to see the wounded.”

The North Koreans were allowing the chaplain to move up and down the valley to visit us. There were about eight hundred prisoners in the valley. Kapaun spent about ten minutes in our house. Some of the guys asked about friends. Kapaun also told us who was dead or wounded. Before he left, he told us to get organized.

“We’ll need to take action when the troops show up,” he said. “Have a plan. When the troops get close, the North Koreans might try and kill us.”

Kapaun believed our troops were close and it was only a matter of time before we’d be liberated. Before leaving, he promised to pray for each one of us. As he left the room and walked away, I stood near the house and watched him go. I didn’t know if he was right about the troops coming or if they were close, but I felt good and couldn’t wait until he returned.

Kapaun never came back to my house, but he continued to visit troops in the valley. I know he prayed for each one of us and when he could, brought food to the starving, until he became so weak that the guards took him to the hospital. He died of pneumonia in May 1951 and was buried in a mass grave by the Yalu River.

I took Kapaun’s warning seriously, and the next day we started to watch the guards religiously, trying to understand their routine. The six guards that patrolled our house were all young and seemed nervous. Two guards each shift manned posts outside the buildings. They would holler at us when we moved too far from the house, but never came close enough to touch us. The goal, when the troops came, was to lure the guards to us and then overpower them. I tapped six of the strongest guys to be ready and to wait for my signal. I wanted to make sure our troops were close before we sprung the plan.

While out getting water one morning, I saw one of the guards bouncing up and down on the ground trying to keep warm. Each time he hit the ground, it gave like it was hollow underneath. I figured it was a root cellar and hoped there was food inside. Since we knew the guards’ patterns, I waited until they were out of sight and dashed to the cellar and threw off the wooden board covering the door.

Inside there were vats of kimchi, a pickled dish of vegetables, mostly cabbage and varied seasonings. It stunk to high heaven, but it was better than the millet. Looking over my shoulder to make sure I was clear, I started to fill two helmet liners full of kimchi. I raced back and another soldier went with two more helmet liners. He was halfway back to the house when the guards appeared. They shouted and he dropped one helmet liner and ran like hell into the house. We waited for the guards to come. We could hear them talking and poking around the cellar, but they never came into the house.

“Maybe we got away with it,” I said.

But I didn’t feel that lucky. The next morning, the guards were at the cellar removing what was left of the kimchi. We usually got a bucket of millet, but this time we only got an English-speaking officer. He was small with a pocked face and dark, piercing eyes and an angry scowl pasted across his lips. I’d never seen the little son of a bitch before. He looked into the room and didn’t say a word. We could feel his eyes on us. Finally, he started to call us one at a time back to the kitchen. I was one of the first to be taken out.

“Who took food? You tell me. You will not get food until you tell. You take food, no?”

I shrugged my shoulders.

“Nope,” I said.

“You go back to room, I will get you again,” he said. “You will tell who took the food.”

When I got back, everyone was quiet. No one looked up at me.

“They’re trying to figure out who took the kimchi,” I said.

They all started talking at the same time in a machine gun burst of nervous chatter.

“Did they do anything to you?”

“Did they threaten you?”

I shook my head no. I tried to stay cool. Fearless. I knew the men were nervous, some scared. But I didn’t want them or the North Koreans to see anything but cool.

“They are going to send for me again,” I said. “That is what the little son of a bitch said.”

Everyone got very quiet again.

“Don’t worry. If I don’t know anything, I can’t tell them anything,” I said with an almost cocky grin.

I kind of liked the little cat-and-mouse game the North Korean officer wanted to play. It kept my mind active and not thinking about food or home.

“But you know,” one of the younger soldiers said.

“Shut up, asshole,” Sergeant Martin snapped. He understood what I was doing.

Everyone sat quietly again. I wondered what I was in for and started to let my mind drift away, repeating over and over to myself that I didn’t know anything.

“If I know nothing, I can’t tell them anything,” I repeated in a steady mantra. “If I know nothing, I can’t tell them anything.”

It wasn’t long before the son of a bitch was back. He threw the door open and pointed at me.

“You come,” he said.

I looked around and finally pointed at myself.

“Me?” I asked. I knew damn well he wanted me, but I wasn’t going to come easily. I wanted the men to see me put up a little bit of resistance.

“You. You. You come.” Now there was no doubt he wanted me. He took me back to the kitchen area and started the questioning all over again.

“Who took the kimchi?”

I shook my head again.

“Your guards took it. We saw them last night and early this morning. Go check.”

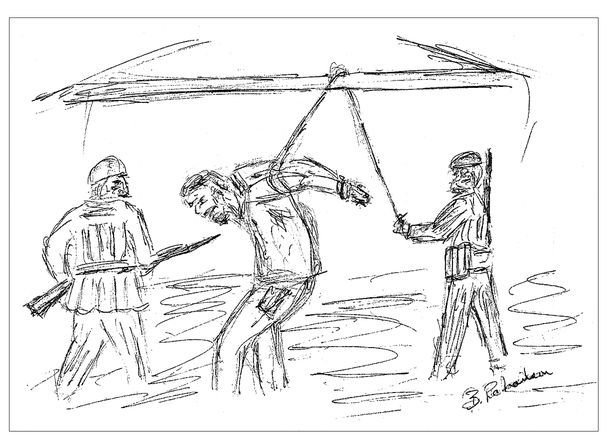

Punishment for stealing kim chi. Sketch by author

I could see the rage building up. He snatched his pistol and started waving it around like a madman. Oh shit, I thought. I was about to get shot over a few handfuls of pickled cabbage.

“You lie. You know and you tell me.”

Eyeing that pistol, I figured I could take him and shove it straight up his ass. But there were two more North Korean soldiers standing behind me.

“Nobody eat until you tell me,” he said.

They had not fed us that morning and it was getting late in the afternoon. I knew the men needed to eat. We were weak and missing a day, even if it was that putrid millet, was out of the question. Plus, there was no telling how long they’d starve us.

Typical Korean hut/house. Sketch by author

“I did it,” I finally said. “Only me.”

Now it was the officer’s turn to shake his head no.

“You lie. More do it.”

“No. Only me and the guards,” I said.

The little son of a bitch looked at me and then nodded to the guards, who grabbed me and tied my arms behind my back.

“You learn lesson now,” the officer said.

The guards threw a rope over an open truss and pulled me up by my arms until my feet barely touched the dirt floor. The pain was excruciating. I could feel lightning jolts of pain in my left arm and shoulder where I still had shrapnel wounds. The pain quickly crept up my arms, driving straight to the top of my head. I gasped for air. The pressure on my chest only allowed me to take sharp short breaths. I could hear myself moaning, and once I cried out in pain before I passed out.

Telegram notice of missing in action status. Author’s collection

Letter confirming status as missing in action. Author’s collection

I woke up on the dirt floor. I could barely feel the guards pulling the ropes off my arms. I could hear the son of a bitch rattle off a few orders. He sounded far away, but I could see his boots and knew he was standing over me. The guards dragged me to my feet. Throwing open the door, they tossed me onto the floor of my room. I could barely move my arms and legs and stayed where I landed the rest of the night. Martin helped me get comfortable and told me that the house had been fed earlier that night. He had no idea how long I’d been strung up.

The next morning, I sat up and started making jokes. Some of them laughed with me. Others were just scared. Laughing hurt my ribs, but it was the first time I’d done it since Unsan. I was determined to keep my sense of humor. It was tied to my will to live. From that point on I remembered to laugh when I could.

“Well, I guess we won’t be having kimchi anymore.”