BY JANUARY 1955, Mao Tse-tung and the Chinese Communist Party had been in power for over five years, after having driven the Nationalist regime of Chiang Kai-shek off the mainland and onto the island of Taiwan. It was during the second week of January that Premier Zhou Enlai met with nuclear scientist Qian Sanqiang, economic affairs official Bo Yibo, and two representatives of the Ministry of Geology, Li Siguang and Liu Jie. Qian, the head of the Institute of Physics, had graduated from the physics department of Qinghua University in 1936, and spent the war years in German-occupied France, doing theoretical work with Irène Joliot-Curie and earning his doctorate from the University of Paris. He had returned to China in 1948, becoming a professor of physics at Qinghua University. Qian provided Zhou with a tutorial on atomic weaponry, as well as an overview of the nation’s nuclear-related manpower and facilities. Zhou interrogated Liu about the geology of uranium, and reviewed the basics of atomic reactors and weapons with Qian. At the end of the meeting, Zhou told his guests to prepare for a repeat performance, this time for Mao and other senior officials.1

On January 15, Mao, senior members of the party’s Politburo, and others met in a conference room in Zhongnanhai, a massive walled compound in Beijing, where China’s Communist rulers resided. There was only one topic on the agenda: the possibility of initiating a nuclear weapons program. Li, Liu, and Qian were there, and it was not long after the meeting began that they were lecturing China’s senior leaders on nuclear physics and uranium geology. In addition to information, the scientists brought along some uranium and a Geiger counter for Politburo members to try out.2

At the end of the meeting there were toasts from Mao and Zhou, with the premier calling on the scientists “to exert themselves to develop China’s nuclear program,” which was given the code designation 02. But it was not the clicks of the Geiger counter that had led Mao to decide, before the meeting ended, that China should acquire nuclear weapons. There had been a war in Korea, whose endgame included a U.S. threat to employ nuclear weapons if an armistice could not be worked out, the confrontation over the Nationalist-held islands of Quemoy (Jinmen) and Matsu (Mazu) that began the previous fall, the U.S.-Taiwan defense treaty signed in December, and a desire for international prestige and influence.3

Mao’s decision was followed on July 4 by the Politburo’s appointment of the unimaginatively named Three-Member Group, consisting of Nie Rongzhen, Chen Yun, and Bo Yibo, to serve as a policy board for the nuclear program. Nie, a senior battlefield commander during the revolution, had served as acting chief of the General Staff from 1950 to 1953. Chen, a senior member of the Politburo as well as vice premier, played a significant role in industrial development. Bo was apparently chosen for his managerial acumen. Two other organizations were established that month to implement Mao’s decision. The Third Bureau, which remained under the Ministry of Geology until November 1956, was to lead the search for uranium. The deceptively named Bureau of Architectural Technology was to supervise construction of the experimental nuclear reactor and cyclotron, which was to be provided by the Soviet Union.4

On November 16, 1956, the Third Ministry of Machine Building, headed by Song Renqiong, was established to direct China’s nuclear industry. Song, who served as a senior commander and political commissar during the civil war, became responsible for the policy direction that had been provided by the Three-Member Group. Before the end of 1959, a reorganization would result in the Third Ministry becoming the Second Ministry of Machine Building, with eleven bureaus to oversee the various stages of atomic bomb production, from uranium mining to bomb design to testing.5

In 1958 a second crisis over the Taiwan Straits, as well as U.S. nuclear weapons deployments on Taiwan, reinforced Mao’s belief that China needed an atomic arsenal. That July also marked the creation of the Beijing Nuclear Weapons Research Institute, China’s temporary counterpart to Sarov and Los Alamos. Heading the institute was Li Jue, an administrator rather than a scientist, who would also be placed in charge of the nuclear weapons bureau (Ninth Bureau) of the Second Ministry.6

For the designs produced by the Beijing institute to progress beyond the blueprint stage, China needed uranium and facilities to turn the uranium into fissionable material and then into bombs. The first phase of that process began shortly after Mao’s decision, when two prospecting teams, Team 309 and Team 519, were sent out to find uranium. By early 1958, their efforts had produced a list of eleven candidate sites, from which eight would be chosen for further investigation. In May, one thousand miners began construction, in Hunan province, of the Chenxian Uranium Mine.7

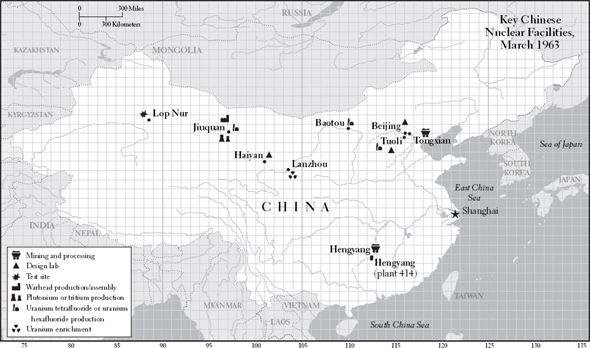

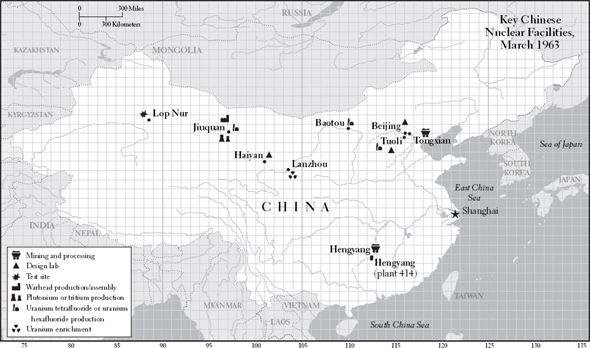

Institutions dedicated to research on the means of getting the most out of the mining effort were also established in 1958. At Hengyang, about 150 miles north of Chenxian, the Uranium Mining and Metallurgy Design and Research Academy was created, to design hydrometallurgical plants and explore the mass production of uranium oxides. That August, construction began on the Hengyang Uranium Hydrometallurgy Plant (Plant 414, later 272), located on the banks of the Xiang River, at the site of a defunct political prison camp, which would process all the ores from Chenxian and other mines using magnetic separators.8

The Second Ministry also created the Uranium Mining and Metallurgical Processing Institute in Tongxian, a few miles east of Beijing, to engage in research on uranium ores and their processing. In August 1960 a subsidiary element of the institute, the Uranium Oxide Production Plant (Plant 2), was established to rapidly produce several tons of the oxide. A few months later the institute was also instructed to build a plant, Plant 4, for the production of uranium tetrafluoride.9

Construction also began in 1958 of two facilities earmarked to provide crucial material for China’s uranium bombs. Baotou, in Inner Mongolia, about 445 miles from Beijing, became the site for the Baotou Nuclear Fuel Component Plant, also known as Plant 202, which would provide uranium tetrafluoride to be converted into uranium hexafluoride and used to produce enriched uranium. In October construction began on Plant 202’s Uranium Tetrafluoride Workshop, and, in 1959, on the Lithium-6 Deuteride Workshop—indicating that China was already looking past the atomic bomb to a hydrogen bomb.10

The site for the Lanzhou Gaseous Diffusion Plant—in a U-shaped valley on the banks of the Huang He (Yellow River) about 15 miles northeast of Lanzhou—had been selected in February 1957. Lanzhou appeared to satisfy several requirements. Its interior location made it difficult for U.S. spyplanes to overfly, while the Huang He provided water that could be used for cooling and power generation (although not without a special filtration system to separate the considerable sediment). In addition, it was necessary to build substantial numbers of converters for the diffusion cascade, pumps, valves, coolers, and instruments, as well as several million feet of corrosion-resistant piping. Lanzhou, with a population of over seven hundred thousand, contained a thermal power plant, nearby coal fields, and assorted machine-building, metallurgy, and chemical factories.11

The year 1958 also saw the beginning of planning for China’s first plutonium production reactor, also in north-central China. Its location at the foot of the Qilian peaks in the isolated Gobi Desert, in the western sector of Gansu province, was selected by Nie Rongzhen. He surveyed the desert area over 185 miles to the west of the ancient town of Suzhou, which had a population of less than fifty thousand. Nie also approved the Soviet designs for the facilities to be constructed and arranged for a workforce of thousands to build them. In August 1959 construction began for the Jiuquan Atomic Energy Joint Enterprise, initially known as Plant 404.12

When completed, the complex included a plutonium production reactor, a chemical separation plant, and more. Its Plutonium Processing Plant would refine the plutonium metal for bombs and warheads. Jiuquan would also be the home of the Nuclear Fuel Processing Plant, for converting enriched uranium hexafluoride to uranium metal, as well as the Nuclear Component Manufacturing Plant. A satellite city was also built, consisting of a large residential area with its own shopping and recreation facilities.13

And in August 1958 a select group of officers and men from the People’s Liberation Army garrison at Shangqiu, in Henan province, boarded a train that took them west in search of a test site. Unlike Kenneth Bainbridge or their Soviet counterparts, they did not know that they were looking for a nuclear test site. All that their secretive superiors had told them was that they would be roaming the western part of China in search of appropriate locations for a secret facility. They were given no information about how long their assignment would take or exactly where it would take them.14

Their first stop, ten days into their journey, was at Dunhuang in northwestern Gansu province. They examined parts of the Gobi Desert, to learn what it would be like when they began their search in earnest. After a week they returned to Dunhuang, sat in a movie theater, and discovered that their real mission had two parts: to choose a location for the test site and then to build it. For the next three months they searched for a suitable location for the site, housing, and command posts.15

By October, while the issue had not been settled, several potential locations had been identified. To bring the selection process to a close, Zhang Yunyu, who had been named commander of the test site, arrived in Dunhuang to personally inspect the alternatives. One potential site, about 85 miles to the northwest, had been recommended by the survey team’s Soviet advisers, with the expectation that explosions at the site would not exceed 20 kilotons, which they considered sufficient for China’s nuclear weapons program.16

However, examination of high-altitude wind direction data at the proposed site eliminated it. Downwind from the test site were the residents of the Dunhuang region, who would suffer the consequences of tests conducted at the Soviet-proposed site. Zhang recommended that the search move to the west, a recommendation accepted by China’s rulers back in Beijing. Zhang stayed in Dunhuang, but ordered the survey team west. They were soon in the county of Turpan, in the Xinjiang Uygur autonomous region, about 340 miles northwest of Dunhuang and north of the Taklimakan Desert. Without adequate maps, survey aircraft conducted initial reconnaissance missions.17

By the middle of December, the aerial surveys had spotted some good candidate sites, and on December 22, survey teams set off to conduct ground reconnaissance. Units of twenty soldiers “covered this ancient kingdom of Loulan by jeep, basically following the routes of the ancient Silk Road between Yanqi and Turpan and Yanqi and Lop Nur,” according to two historians of the Chinese program.18

In the winter of 1958–1959, one of the teams arrived at the oasis Huangyanggou and liked what they found. The surrounding area was a large desert valley, more than 60 miles wide and 37 miles long, with the Tian Shan mountain range to the north. Water was readily available for both drinking and construction. There were no residents within 280 miles in the downwind direction and no significant settlements within a 140-mile radius. It would be possible, further examination revealed, to satisfy the requirements for a ground zero and a command post close enough to each other to permit observation without risking the lives of the observers. On October 16, 1959, the Lop Nur Nuclear Weapons Test Base was established.19

Originally Mao and his cohorts expected that the first device tested at Lop Nur would be built with considerable Soviet assistance, and for several years it looked as if he would get it. In mid-January 1955, the Soviets had announced that they would provide assistance to China and several East European nations in the field of peaceful uses of atomic energy. Their help to China would include a cyclotron, a nuclear reactor, and fissionable material for research. Altogether, between 1955 and 1958 the Soviet Union and China reached six agreements on nuclear issues, including the October 15, 1957, New Defense Technical Accord, which contained a Soviet promise to provide a prototype atomic bomb and missiles, along with related technical data.20

But by 1959 the Sino-Soviet alliance was in the process of falling apart. Since 1956 Mao’s regime had been issuing grand pronouncements on both domestic and foreign policy issues that were more radical and truculent than Soviet policies. One casualty was the atomic assistance pacts. In June 1959 the Soviets notified the Chinese Communist Party that they would not provide promised mathematical models and technical information to assist the Chinese effort. It was a refusal that signified the deterioration of relations between the Communist states as well as accelerated the decline. By the time Soviet assistance ceased, in 1960, the Soviets had not delivered a single key component for the plutonium production reactor to be built at Jiuquan, much less the “sample” bomb.21 The Chinese were now on their own, and that would have a substantial impact on the road they took to get to the front door of the nuclear club.

The Soviet reversal also meant that China would have to place greater reliance on its own nuclear physicists, including Deng Jiaxian, Yu Min, Peng Huanwu, Guo Yonghuai, Hu Side, and Wang Ganchang. Deng had earned his doctorate in the United States, from Purdue University in 1950, and returned to China that same year, helping to establish the Chinese Academy of Sciences’s Institute of Modern Physics (“Modern” subsequently being deleted from its name). He was also among the founders of the Beijing Nuclear Weapons Research Institute, where he headed the Theoretical Forum, which examined the theory of bomb design. Yu Min, unlike Deng, gained his doctorate from a Chinese university, enrolling in the graduate program in the physics department at Pekin University in 1949, at the age of twenty-three. In 1960 he began theoretical research on nuclear weapons, eventually becoming Deng’s deputy. By the time Yu began his graduate work, Peng, born in 1915, had obtained two doctorates, one from Edinburgh University, where he had studied under Max Born and became well known for his work on quantum field theories and cosmic rays.22

In 1935, at the age of twenty-six, Guo Yonghuai left China with an undergraduate degree in physics from Beijing University and headed for Canada and the applied mathematics department at the University of Toronto, which awarded him a master’s degree in 1940. His next stop was the California Institute of Technology, where his studies on compressible fluid mechanics culminated in his receiving a doctorate in 1945. The next year he began a seven-year stay at Cornell, leaving in 1953 when the United States lifted its prohibition on Chinese students leaving the country. Five years later he became the first head of the chemical physics department of the China Science and Technology University. In 1960 he was appointed a deputy director of the Beijing Nuclear Weapons Research Institute.23

Wang Ganchang, an expert in radioactivity and bubble chambers, graduated from Qinghua University in 1929, did his graduate work in Germany, studied under Lise Meitner at Berlin University, received his doctorate in 1934, and returned to China that same year. In 1956 he was a researcher at the Dubna Integrated Atomic Nuclear Institute in the Soviet Union. After his return, he became deputy director of the Institute of Atomic Energy.24

WHEN JOHN F. KENNEDY sat behind his desk in the Oval Office for the first time, he knew little about how China’s quest for an atomic bomb had progressed over the previous six years. But it was not because he had not yet been briefed. The CIA and America’s other intelligence agencies, despite the imagery provided by Corona and U-2 missions and the efforts from 1957 of modified Navy P-2V Neptune aircraft to detect the signatures of atomic activity (in addition to their main electronic intelligence mission), knew little of what the Chinese were doing or had done in the atomic field. China was, former OSI chief Karl Weber recalled, “a real mystery . . . big, really foreign, hard to get a handle on.”25

That mystery was reflected in the intelligence reports that had been prepared on the Chinese program. In June 1955 Sherman Kent, the head of the CIA’s Office of National Estimates, prepared a short memorandum on possible Chinese development of atomic weapons and delivery systems. The fifty-two-year-old Kent, the son of a three-term California congressman, had received a doctorate in history from Yale in 1933, and during World War II had served in the OSS research and analysis branch as a division chief. After a brief postwar tour in the State Department’s intelligence office he returned to academic life. Then, in late 1950 he joined the CIA as deputy chief of the national estimates office, becoming its head in 1952. In a volume of essays in his honor, he was described as “perhaps the foremost practitioner of the craft of analysis in American intelligence history.”26

Kent concluded that “China almost certainly would not develop significant capabilities for the production of nuclear weapons within the next 10 years unless it were given substantial external assistance.” Without such assistance, development of an effective nuclear weapons program “would probably take well over 10, and possibly 20 years.” Kent based his assessment on what he knew or believed about China’s scientific and industrial capabilities—including its lack of an ability to process uranium ore as well its having “almost no scientific tradition in theoretical and experimental physics”—and his assessment of China’s willingness to divert significant resources from conventional economic and military needs.27

But Mao and his associates had decided to divert the resources necessary, and by 1960 China was actively engaged, without Soviet assistance, in constructing its first generation of atomic facilities. To the extent that the CIA and other agencies could photograph such activities, intercept signals about them, and recruit spies who could explain their significance, U.S. analysts might be able to accurately assess the status of the Chinese program. To help the intelligence collectors in their task, in October 1960, the OSI requested the geography division of the agency’s Office of Research and Reports to analyze the geography of China in order to identify the most likely locations for reactors, gaseous diffusion plants, and test sites.28

That very request demonstrated how little the United States knew about Chinese atomic activities, an ignorance that was reflected in key intelligence estimates published at the end of the year. A national intelligence estimate issued on December 6 noted that “our evidence with respect to Communist China’s nuclear program is fragmentary as is our information about the nature and extent of Soviet aid.” Seven days later, another estimate, The Chinese Communist Atomic Energy Program, spelled out what little America’s intelligence agencies knew or believed.29

The December 13 estimate, which one State Department official described as “one of the most significant recent intelligence products,” was considerably different in tone from Kent’s analysis half a decade earlier. It noted that China was “energetically developing her native capabilities in the field of atomic energy,” a conclusion based in part on the images brought back from a September 1959 U-2 mission, which revealed a two-thousand-foot-long building at Lanzhou that had some of the characteristics of a Soviet gaseous diffusion plant. In addition, China had “acquired a small but highly competent cadre of Western-trained Chinese nuclear specialists.” The authors also mentioned a number of concrete manifestations of the Chinese program, including indications that its control was vested in the Second Ministry of Machine Building. Further, China was probably constructing ore concentration and uranium metal plants, and over ten uranium ore deposits were being mined.30

The big question, just as it had been with the Soviet Union in the late 1940s, was when. CIA analysts assumed China would conclude—as had the Soviets, British, and French—that the plutonium route to the bomb was the easiest. They estimated that China’s first plutonium production reactor could go critical in late 1961, with the first plutonium possibly becoming available in 1962. The most probable date for a test was sometime in 1963, but possibly as late as 1964 or as early as 1962. Much would depend on the extent of Soviet assistance, which the analysts noted might decline as a result of the tensions between the two Communist powers.31

During 1961, while analysts at the CIA and the other intelligence agencies tried to determine exactly what progress China had made toward an atomic capability, other elements of the government began to explore the implications of such a capability, and what the United States might do to lessen or eliminate its impact.

A June 1961 report produced for the Joint Chiefs of Staff concluded that Chinese “attainment of a nuclear capability will have a marked impact on the security posture of the United States and the Free World, particularly in Asia.” A few months later, George McGhee, the State Department’s director of policy planning, suggested that China’s acquisition of nuclear weapons would pose more political and psychological problems than military ones. According to that study, a nuclear China could reap politically significant “psychological dividends” by helping to create the impression that “communism is the wave of the future.” For many Asians, a nuclear test would raise the credibility of the Communist model for organizing a backward nation’s resources as well as their estimates of Chinese “military power relative to that of their own countries and the [United States’] capabilities in the area.” A heightened sense of China’s power could create a bandwagon effect, with greater political pressures on states in the region to accommodate Beijing and loosen ties with Washington.32

McGhee suggested to secretary of state Dean Rusk that one way to reduce the psychological impact of a Chinese bomb was to encourage, and perhaps even assist, India to develop a bomb. India’s atomic energy program, McGhee informed his boss, was sufficiently advanced so that within a few months it could produce enough fissionable material for an atomic device. McGhee wanted a noncommunist Asian state to “beat Communist China to the punch.” While it would be difficult, he wrote, to get Indian prime minister Jawaharlal Nehru, an opponent of nuclear testing, to approve, he might be “brought to see the proposal as being in India’s interests,” since an Indian bomb could neutralize any Chinese attempts to employ nuclear blackmail against India and its neighbors.33

McGhee’s scheme found uneven support at the State Department, and it was diluted to a quiet, exploratory effort by White House science adviser Jerome Weisner during his upcoming trip to South Asia. Weisner would meet with Homi Bhabha, the chairman of India’s Atomic Energy Commission, and inquire about the effect a Chinese nuclear weapons capability might have on India’s nuclear program, a question that might lead to an Indian request for assistance. The proposal was approved by undersecretary of state Chester Bowles but vetoed by Rusk, who was not convinced that “we should depart from our stated policy that we are opposed to the further extension of nuclear weapons capability.” If the United States abetted nuclear proliferation, Rusk argued, it “would start us down a jungle path from which I see no exit.”34

THROUGHOUT 1961 and into 1962, the State and Defense Departments as well as the National Security Council (NSC), the latter at Kennedy’s urging in January 1962, pondered what might be done about the embryonic Chinese nuclear program. Meanwhile, the intelligence community sought to accumulate more information about it. In October 1961, the CIA’s Central Intelligence Bulletin noted that Lo Jui-ching, the People Liberation Army’s chief of staff, had “reaffirmed China’s determination to become a nuclear power.”35 But, as expected, he provided no details about China’s quest.

Providing those details was partially the responsibility of the Corona satellites. While there had been only one successful Corona mission prior to the December 1960 national estimates, eight additional successful Corona missions had been conducted through the end of February 1962. Whatever intelligence on Chinese atomic facilities had been derived would have been available to to the CIA analysts when they began preparing the April 1962 national intelligence estimate titled Chinese Communist Advanced Weapons Capabilities. Not only were there more photographs that could be exploited, but they were of higher quality. Instead of the KH-1 camera, with its forty-foot resolution, which produced the imagery employed in the 1960 estimates, the eight missions employed the KH-2, KH-3, and KH-4 cameras, each with progressively higher resolution. A December 1961 KH-3 mission provided the first imagery of Lop Nur since the Chinese had selected it as a site, although CIA photointerpreters only recognized it as a “suspect site” at the time.36*

In addition to the imagery from Corona missions, there were even higher-resolution images, albeit far fewer of them, from U-2 missions. Beginning in 1961, under a program designated Tackle, U.S.-trained Chinese Nationalist pilots, known as the “Black Cat” squadron, began flying over China from a base at Taoyuan on Taiwan. Despite the substantial risk involved, they were able to cover a number of mainland targets, flying as many as three missions a month, some of the pilots penetrating Chinese airspace for eighteen hundred miles before turning back. While Lop Nur was beyond their reach, possible atomic sites in north-central China were not.37 The increased imagery, however, still left much in doubt.

The September 1959 images of of the Lanzhou building that had some of the characteristics of a gaseous diffusion plant revealed “no . . . provision for an electric power supply.” Imagery from a Corona mission in late February and early March 1962 showed “no further indication of provision for an electric power supply or of preparation for construction of a second building,” a building that would be needed to obtain weapons-grade U-235. The analysts went on to note that the Corona photographs showed “arrested development” at a nearby hydroelectric power station. Thus, if “the [Lanzhou] site were to be a gaseous diffusion plant, the Chinese probably could not produce weapon-grade uranium-235 there before 1965, even if construction of another building were started now.”38

The photography turned up no evidence that China was building a plutonium production facility: “recent photographic coverage of certain suspect areas produced negative results.” It was possible, according to the authors of the estimate, that a production reactor was located outside the area covered. Despite the lack of supporting evidence, the estimators continued to assume that China was taking the plutonium path to the bomb. “Assuming,” they wrote, “an accelerated and highly successful program for the production of plutonium since 1960, the Chinese Communists could detonate an all-plutonium device in early 1963.” They considered it unlikely, however, that the Chinese would meet such a schedule, and predicted that the “first Chinese test would probably be delayed beyond 1963, perhaps as much as several years.”39

The conclusions of the April and subsequent intelligence reports helped reinforce the need to examine the implications of, and policy options to deal with, a Chinese nuclear capability. In August, a group of RAND Corporation analysts concluded that a nuclear-armed China would pose a significantly broader challenge to America’s position in Asia than it had previously, and was most likely to exploit its new status in the political arena and through low-level military operations. They also noted that while the pronouncements of Chinese leaders created an impression of recklessness and irresponsibility, their statements appeared to be “motivated by the internal and international value they derive from creating and maintaining the image.” In contrast, actual Chinese behavior and doctrine “place a great emphasis on a cautious and rational approach to the use of military force.”40

The following month Dean Rusk approved a new proposal from policy-planning chief George McGhee, this one for a coordinated overt-covert propaganda campaign that would involve the State and Defense Departments and CIA. The campaign would combat the “vast ignorance and strong emotionalism” in most of Asia with regard to nuclear matters, heighten Asian awareness of “U.S. and Free World strength,” and neutralize “awe and unreasoned fear” of China. Besides emphasizing the United States’ strategic nuclear superiority, the campaign would suggest that China’s nuclear program was behind schedule, in hopes of producing a “what took you so long” reaction to any Chinese detonation.41

Along with the efforts to shape world opinion, Robert Johnson, an East Asian specialist, began a series of major studies on the implications and consequences of a Chinese nuclear test and a “regionally significant” nuclear capability. Johnson had arrived in Washington in 1951 to work at the NSC, after obtaining his doctorate from Harvard and spending a couple of years teaching there. His graduate work had been in political economy and government, not Asia, but during his first decade at the NSC a Rockefeller Public Service Award allowed him to spend ten months traveling through Asia, working on a project on Chinese and Indian influences in the region. He “went around and talked to all sorts of people,” he recalls, “got a good education on Asia,” and found out that “neither [India nor China] had much influence.”42

When the Kennedy administration took office, most of the NSC staff were sent elsewhere, but Johnson remained and was assigned responsibility for East Asia. By the fall of 1962 he had been transferred to the State Department’s policy-planning unit to be its East Asia expert. His mandate was not only to determine the impact of a Chinese nuclear capability but also to consider the policy changes that might be needed to counter its political and diplomatic effects.43

EARLIER THAT YEAR, the Uranium Mining and Hydrometallurgy Institute at Tongxian (Plant 4) had begun producing uranium tetrafluoride in quantity. In September the nation’s senior defense and nuclear officials, after reviewing the progress of the nuclear program, proposed that China try to test an atomic bomb within two years. The following month Li Jue and other leaders of the Beijing institute provided senior officials with their plan to bring China into the nuclear club during the winter of 1964. It was probably that plan that led officials from the Second Ministry to order the Lanzhou gaseous diffusion plant to produce the necessary highly enriched uranium six months ahead of schedule—by early 1964. Then, in November the Chinese Communist Party Central Committee established the fifteen-member Central Special Commission, lead by Zhou Enlai, to oversee the nuclear weapons program.44

Not long after its establishment, the commission speeded up the planned move of Li Jue’s institute from Beijing to Qinghai province, where it would become the Northwest Nuclear Weapons Research and Design Academy, more discretely known as the Ninth Academy. The commission accelerated work on key buildings, including those for neutron physics and radiochemistry. Finally, in March 1963 some sections of the Beijing institute began to move to their new home.45

The institute’s scientists found themselves in a very different environment than Beijing—much the same as Oppenheimer and scientists from Berkeley, Chicago, and New York did when they moved to an isolated part of New Mexico, or as Andrei Sakharov did when he left Moscow for Sarov. Qinghai, in China’s remote northwest, was isolated and largely inaccessible, which satisfied the key criteria of the Chinese officials responsible for selecting the site for the nation’s weapons design bureau.46

Beyond movement of personnel, there was also movement toward the day when China would test an atomic bomb. The Institute of Atomic Energy (initially code-named 601 and later 401) had grown out of the Institute of Physics, and its scientific activities were conducted in Touli, a town about twenty miles south of Beijing. Sometime before July 1960 it had been assigned the task of beginning research and development on the production of uranium hexafluoride. By October 1963 it had produced enough to send to Lanzhou for test runs of the plant’s diffusion cascade. In November the plant in the Jiuquan complex also produced satisfactory uranium hexafluoride, while Plant 414 at Hengyang produced uranium oxide that was sufficiently pure to justify the plant beginning mass production.47

IF THE CIA and other interested intelligence agencies had known of the developments in 1962 and 1963, they would have revised at least one key assumption about the Chinese program: that it revolved around the production of plutonium. But their knowledge of China’s efforts was still limited. On January 10, 1963, former Atomic Energy Commission chairman John McCone—who replaced Allen Dulles as director of central intelligence in November 1961 after Dulles was forced to depart because of the Bay of Pigs fiasco—met with McGeorge Bundy, Kennedy’s national security adviser. Bundy described the president’s fear that a nuclear China “would so upset the world political scene [that] it would be intolerable.” Further, Bundy told the intelligence chief that Cuba and the Chinese nuclear program were the “two issues foremost in the minds of the highest authority and therefore should be treated accordingly by CIA.” McCone had to acknowledge, however, that the agency knew little for certain about China’s progress—hence the need for an expanded effort.48

In the months that followed, pilots from the Black Cat squadron flew their U-2s over China, as they had throughout 1962—although not without the occasional loss of plane and pilot. A March 1963 flight detected the nuclear complex at Baotou. Satellite coverage was also increasingly routine, allowing photography of parts of China, including the suspect site at Lop Nur, that were out of range of the Taiwan-based U-2s. Launch crews at Vandenberg Air Force Base in California successfully orbited five Corona satellites, each equipped with the advanced KH-4 camera system, during the first half of the year. Intelligence from those missions would be added to whatever had been acquired from the thirteen 1962 Keyhole missions whose imagery became available after the April 1962 national estimate was prepared.49

In July a new type of imaging satellite was added to the U.S. arsenal when the first Gambit satellite, carrying the KH-7 camera, went into orbit. Whereas the Corona satellites performed an “area surveillance” mission, Gambit was designed for a “close look” mission. Its lower orbit was one reason why a photograph taken by a KH-4 camera included 1,075 square nautical miles, but one taken by a KH-7 camera covered a mere 120 square nautical miles. However, whereas the KH-7 saw less, what it did see it saw much more clearly. In contrast to the ten- to twenty-five-foot resolution of the KH-4, the initial resolution of the KH-7 was, at its best, four feet. The combination of higher resolution and the camera’s ability to take oblique shots was of particular value in photographing nuclear installations. Interpreters examining KH-7 images of the sides of nuclear facilities could determine the size and shape of the transformers, allowing an accurate assessment of how much power was being used.50

July was also marked by two estimates summing up what the U.S. intelligence community knew or believed about the Chinese program. The first, issued on July 10, two days before the first KH-7 camera was placed into space, was the work of the Arms Control and Disarmament Agency (ACDA). The second, a special national intelligence estimate—SNIE 13-2-63, titled Communist China’s Advanced Weapons Program—was in draft form at that time, although it was formally approved by the U.S. Intelligence Board on July 24.

Both estimates devoted considerable attention to Lanzhou and Baotou. The national estimate reported that photography of Lanzhou, obtained that March and June, showed progress being made on a nearby hydroelectric installation, which intelligence experts believed was designed to supply the plant. Although much work remained to be done, some power was available. In addition, the analysts reported two transmission lines, one of which appeared to be completed, connecting the diffusion plant with a thermal electric plant at Lanzhou. There was also a substation at the diffusion plant, and, it was noted, the installation of transformers alongside the main building had begun, although only two of a probable thirty-eight were shown to be in place.51

The national estimate also informed its readers that the main building at Lanzhou was big enough to allow for the production of lightly enriched uranium, which could be used in reactors. It would take at least twice as much floor space than provided by that building to produce weapons-grade U-235, according to the analysts, who also noted the existence of an adjacent area within the facility’s security perimeter that was apparently intended to allow the required expansion. However, even if “work was underway and all of the highly specialized separation equipment was promptly available, the earliest date at which weapon-grade U-235 could be produced would be in 1966.” A more likely time was 1968–1969, “considering the great technical difficulties involved and the large amount of additional construction needed.” Had the analysts known that the Second Ministry of Machine Building had directed Lanzhou to produce enough uranium for a bomb by the beginning of 1964, they might have had second thoughts about their projection.52

The ACDA study, not surprisingly, echoed the national estimate’s findings with regard to Lanzhou, although it added some details that helped explain the estimate’s conclusions. The size of the existing diffusion building, approximately 1,900 feet by 150 feet, was large enough to contain about eighteen hundred compressor stages. However, at least double the floor space, enough for about four thousand stages, would be required to produce uranium enriched to 93 percent U-235.53

With respect to work at Baotou, the national estimate noted that recent photographs of the area revealed a facility with “elaborate security arrangements.” Its authors believed that a small air-cooled plutonium production reactor, with a capacity of about 30 megawatts, was part of the installation, along with related chemical separation and metal fabrication facilities. The reactor was judged to be sufficient for a token weapons program, but not for “a sizable . . . program based on plutonium alone.” Whether the reactor was in operation, they reported, could not be determined from the photographs.54

In the absence of hard data, the analysts considered alternative scenarios. If the reactor was in operation, they did not believe it could have reached criticality before early 1962. An additional twenty-one to twenty-four months would be needed for the completion of the process—one year for fuel element irradiation within the reactor and an additional nine to twelve months for cooling of the irradiated fuel, chemical separation, and fabrication of a device. Therefore, the earliest a device could be ready would be early 1964. However, running into even normal difficulties would postpone the date to late 1964 or early 1965. If the reactor reached criticality later than early 1962, the date of the first detonation would be delayed even further.55

The analysts also suggested that China must have planned to construct other plutonium production facilities, based on the belief that the Chinese program called for composite weapons containing both U-235 and plutonium. In that case, the quantity of plutonium that could be produced at the reactor believed to exist at Baotou was far too small to be compatible with the amount of U-235 that could be produced at Lanzhou. However, there had been photographic coverage “of many of the likely areas for reactor sites without identifying another production reactor, and there is no significant collateral evidence indicating the existence of such a reactor.” But the estimators could not exclude the possibility that there were other, undetected plutonium production facilities under construction. If that were the case, “the Chinese could have a first detonation at any time.”56

As with Lanzhou, the conclusions of the ACDA report on Baotou were derived from the the national estimate. It also, once again, provided some additional information, including the facts that the entire area was enclosed by multiple fencing and a wall with guard towers at the corners and, more importantly, that the Baotou “reactor” was too small to produce enough plutonium in a year for more than one or two weapons. The ACDA study also devoted a paragraph to two locations in the vicinity of Beijing where nuclear research was underway, both elements of the Institute of Atomic Energy. It noted that the research at the location twenty miles southwest of Beijing, at Touli, involved a Soviet-supplied heavy-water reactor as well as a Soviet-supplied cyclotron.57

The authors of the national estimate acknowledged that despite the influx “of a considerable amount of information, mainly from photography . . . the gaps in our information remain substantial and we are therefore not able to judge the present state or to project the future of the Chinese program as a whole with any very high degree of confidence.” What they did not, and of course could not, tell their readers was what they did not know: the role of the Institute of Atomic Energy at Touli in producing ten tons of hexafluoride for Lanzhou, or the mission of the Jiuquan complex. Nor could they report the extent of their errors. Lanzhou was months, not years, away from producing enough highly enriched uranium for a weapon, while Baotou had been established to produce uranium tetrafluoride not plutonium. Chiang Kai-shek’s intelligence services believed that the Lanzhou reactor was active during 1963, but no one in Washington appears to have given any credence to that report.58

THE ESTIMATE, looking beyond questions of how and when China might first achieve an atomic capability, also explored the ultimate concern of U.S. policymakers—how China’s behavior might change once it had a nuclear arsenal. The estimators “did not believe that the explosion of a first device, or even the acquisition of a limited nuclear weapons capability,” would result in China adopting “a general policy of military aggression or even be willing to take significantly greater military risks.” Chinese leaders, it was expected, would realize just how limited their capabilities were. Yet the estimate also suggested that “the Chinese would feel very much stronger and this mood would doubtless be reflected in their approach to conflicts on their periphery. They would probably feel that the U.S. would be more reluctant to intervene on the Asian mainland and thus the tone of Chinese policy would probably become more assertive.” In a footnote, the acting director of the State Department’s group of intelligence analysts—the Bureau of Intelligence and Research (INR)—noted that the two conclusions appeared contradictory.59

About the same time, a State Department colleague, Walt Rostow, George McGhee’s successor as policy-planning director, gave a less ambiguous assessment. Rostow was undoubtedly influenced by Robert Johnson’s two-hundred-page study, A Chinese Communist Nuclear Detonation and Nuclear Capability, whose conclusions about the consequence of a Chinese bomb were “generally quite sanguine,” Johnson recalls. Rostow wrote that the minimal nuclear capability Beijing could develop was unlikely to “convince . . . anyone” that it could be “used as an umbrella for aggression.” Not only would “U.S. overwhelming nuclear superiority” deter Beijing, but also its “desire to preserve its nuclear forces as a credible deterrent might tend to make China even more cautious than it is today in its encounters with American power.”60

But the argument that China might behave itself when it became a nuclear power did not prevent President Kennedy from exploring how to rein in, or even “take out,” China’s nuclear program. In his January meeting with McCone, McGeorge Bundy said that Kennedy believed “we should be prepared to take some form of action unless they [the Chinese] agreed to desist from further efforts in this field.”61

By the time the ACDA study and special national intelligence estimate were issued, the State Department, the office of the assistant secretary of defense for international security affairs, and the JCS had explored a variety of options. More importantly, on July 14 the undersecretary of state for political affairs, Averell Harriman, arrived in Moscow to try to finalize an agreement on a treaty banning nuclear tests in the atmosphere, in outer space, or under water. Harriman had a second mission. He was to emphasize to Khrushchev that a nuclear China, even as a small-scale nuclear power, “could be very dangerous to us all.” The president wanted Harriman to explore Khrushchev’s views on “limiting or preventing Chinese nuclear development and his willingness either to take Soviet action or to accept U.S. action aimed in this direction.”62

Harriman succeeded in finalizing the agreement on the test ban treaty. But any cables he sent back to Kennedy reporting on his second mission would have been disappointing to the president. Khrushchev proved uninterested in taking any action, even political, against China. As long as France was unwilling to sign the test ban treaty, he would not agree to isolate Beijing. The Soviet ruler also played down the Sino-Soviet split and rejected the idea that a nuclear China would threaten the Soviet Union. Nor did he agree that a nuclear-armed China would be a threat to others, claiming that Beijing would become “more restrained”—“whenever someone lacked [nuclear] means he was the one who shouted the loudest.”63

But Khrushchev’s reassurances and lack of interest did not soothe Kennedy or end U.S. interest in finding a way to stop China’s nuclear quest. In an August 1 press conference, Kennedy spoke of a “menacing situation.” He noted that it would take some years before China became “a full-fledged nuclear power,” but “we would like to take some steps now which would lessen that prospect.” The day before, William Bundy, McGeorge’s brother and assistant secretary of defense for international security affairs, tasked the JCS to develop a contingency plan for a conventional attack designed to cause “the severest impact and delay to the Chinese nuclear program.”64

And while the Soviet Union may not have been interested in taking action against China and its nuclear program, another country was not only willing but eager. In September, Gen. Chiang Ching-kuo—Chiang Kai-shek’s son, minister of defense, and much-feared “security czar”—visited Washington. There he met with central intelligence director McCone to discuss long-standing differences between the United States and Taiwan over military operations against the People’s Republic. A day after meeting McCone, he met with President Kennedy.65

Undoubtedly fearing that a China with nuclear weapons would eliminate any possibility of a return to the mainland, Chiang Ching-kuo raised on several occasions the issue of attacking China’s nuclear facilities. At CIA headquarters, he participated in discussions on the possibility of an air strike. Later, in the company of Ray Cline, the deputy director of intelligence and the agency’s former station chief in Taiwan, and William Nelson, Cline’s successor as chief of station, Chiang met McGeorge Bundy. He suggested that the United States provide “transportation and technical assistance” for a commando attack on the Chinese nuclear installations. Bundy told Chiang that the “United States is very interested in whether something could be planned” that would have a “delaying and preventive effect on the nuclear growth of China.” Such measures, he cautioned, needed “most careful study.”66

On September 11 an extended discussion between Kennedy and Chiang prompted the president to question the feasibility of sending commandos against Chinese nuclear installations. He asked “whether it would be possible to send 300 to 500 men by air to such distant . . . atomic installations as that at Baotou, and whether it was not likely that the planes involved would be shot down.” Chiang reassured Kennedy that the commando raid proposal “had been discussed by CIA officials yesterday and they had indicated that such an operation was feasible.” Kennedy’s query suggested some doubts about the proposal’s feasibility, and other comments emphasized the importance of “realistic” plans to “weaken the Chinese Communist regime.” To avoid another Bay of Pigs operation “based more on hope than on realistic appraisals,” Washington and Taipei needed better intelligence about conditions on the mainland. In that way, Kennedy observed, “whatever action is undertaken would fit the actual situation.”67

A few days later, Chiang met with McCone to formalize the understandings he had reached with Kennedy and his advisers. With respect to possible action, McCone and Chiang agreed to establish a planning group to study the feasibility of attacks by Nationalist teams against China’s nuclear sites. Any operations would require joint approval by their nations’ highest authorities.68

In the weeks after Chiang Ching-kuo’s visit, the Kennedy administration continued to review ways of preventing China from acquiring an atomic bomb. The CIA as well as the Pentagon studied the possibility of air dropping Taiwanese sabotage teams and other covert options. On November 18 Maxwell Taylor, chairman of the JCS, informed his colleagues that their next meeting would include a discussion of “how we can prevent or delay the Chinese from succeeding in their nuclear development program.” Kennedy’s favorite general noted that developing an atomic bomb was “fraught with troubles—technological, scientific, economic, and industrial.” A coordinated program of covert activities designed to intensify those troubles could significantly delay the Chinese program. The title of the agenda item—“Unconventional Warfare Program BRAVO”—indicates that a paramilitary action was to be considered. That such an action had been examined seriously is indicated by the unsuccessful attempt in the fall of 1963 to fly a U-2 equipped with an infrared camera over the suspected plutonium reactor at Baotou. The objective was to determine whether the reactor was in operation, and thus off limits to military attack.69*

In addition, the JCS responded to William Bundy’s request for a contingency plan for a conventional attack to retard Chinese nuclear development. In mid-December, they completed a plan for a multiple-sortie attack designed to inflict severe damage and delays. Nevertheless, the large number of sorties required probably led the JCS to propose looking into a possible nuclear attack on the same facilities, an idea that was obviously rejected.70

Kennedy was willing to consider more than military options. He and his advisers sought to obtain Soviet cooperation on a nonproliferation agreement that would be aimed, in part, at China. Rusk discussed the issue with Soviet foreign minister Andrei Gromyko at the United Nations in the fall of 1963. Gromyko then discussed the issue with Kennedy on October 10. Showing some willingness to exert indirect pressure on China, Gromyko acknowledged that an agreement would make China’s “political situation more difficult and delicate,” presumably by increasing its isolation and raising pressures on it to follow nonproliferation standards.71

THE UNITED STATES began 1964 with a new president, Lyndon Baines Johnson, after John Kennedy was assassinated in Dallas on November 22. In China, Mao and Zhou were still in charge, and China continued its pursuit of an atomic bomb. On January 14, 1964, Wang Jiefu, the director of the Lanzhou plant, and his colleagues arrived at the central control department, where Wang ordered the enriched uranium to be siphoned off into special containers. That was done at 11:05 that morning, with the goal of producing 90 percent enriched uranium achieved. The following day the Second Ministry sent a message of congratulations to the plant and a report to Mao, who scribbled “very good” on his copy.72

A few months later the Nuclear Component Manufacturing Plant at the Jiuquan complex produced the first nuclear components for the bomb, although it had been a struggle. Producing a uranium core had run into a variety of problems, including the development of air bubbles in the casting. Alternative plans and techniques were tried, and data collected, in a series of experiments. One promising approach, when tested, proved successful. On April 30, technicians at Jiuquan began machining a uranium core. By the early morning of May 1, the first core was ready, but not until after there had been a slight mishap due to a technician’s stage fright.73

Then, on June 6 the Northwest Nuclear Weapons Research and Development Academy (the Ninth Academy) conducted a full-scale simulated detonation test, lacking only the nuclear components. The test was successful, indicating that the device would detonate as designed. In July and August the technical staff at the Northwest academy assembled three bombs, putting together the explosive assembly, tamper, uranium core, and initiator plus electrical assembly.74

On August 19, with pairs of white and velvet curtains draped over the windows to keep the sunlight out, what was apparently the assembly of the third bomb began. Electrostatic copper wires had been installed at the doors to ground the static electricity of anyone entering the assembly area. The first stop for those who would handle the assembly was a room where they changed into white coveralls and cloth slippers. The workers also received a message of encouragement and warning from Mao and Zhou, who told them to “be bold but cautious.”75

Their boldness and caution would have to be exercised in view of two high-ranking dignitaries who were there to watch the assembly process. One was Zhang Aiping, head of the First Atomic Bomb Test Commission and the First Atomic Bomb Test On-Site Headquarters. The fifty-six-year-old Zhang had served as deputy chief of the People’s Liberation Army general staff, as chief of staff for the Advance Command of the Taiwan Liberation Forces in Fujian, and as deputy director for the National Defense Science and Technology Commission, an appointment he had had since 1961. The other was Liu Xiyao, the vice minister of the Second Ministry. The assembly was a prolonged process, even without glitches. It would take two days from the time it began until the assembly team reached the last item on its checklist. At that point Zhang and Liu were invited to approach the security line and supervise the insertion of the uranium core into the shell case. When that was completed, the two senior officials applauded.76

In mid and late August the devices, minus the enriched uranium components, were shipped on a special train to Lop Nur, under conditions of extreme secrecy. The train was escorted by armed police, while the route was protected by police from the Ministry of Public Security. All the coal used for the train was sifted to make sure there were no hidden explosives, waiting to derail China’s first nuclear test. In addition, the regions that the train passed through had their high-voltage power cut off. When the devices arrived at the station, they were then taken by truck to the test base.77

Getting Lop Nur ready for the detonation was the responsibility of Zhang Aiping and two key subordinates, test base commander Zhang Yunyu and scientist Cheng Kaijia. During the summer before the bomb had been assembled, their crews had put up an iron tower with an elevator that would carry “596,” as the bomb was designated, approximately four hundred feet above ground.78

TO GET A FIX on China’s nuclear progress, the U.S. intelligence establishment worked overtime to penetrate the ring of secrecy surrounding the effort. Early in 1964, Robert Johnson and other officials at the State Department read CIA reports stating that Chinese officials had said that the first test would “definitely” occur in 1964. China expert Allen Whiting, an INR analyst at the time, recalled reading agent reports on Premier Zhou Enlai’s visit to Mali. According to one of those reports, Zhou told Premier Mobido Keita that China would test a bomb in October. In mid-March the CIA reported that Soviet delegates to the International Atomic Energy Agency (IAEA) believed that China already had a nuclear device and would be capable of detonating it in no more than a year. Nevertheless, no one yet regarded such reports as decisive; thus, Robert Johnson wrote, “We really don’t know when the first detonation would occur.”79

Overhead reconnaissance efforts were particularly important. U-2 missions flown by the Black Cat squadron helped monitor developments at Lanzhou and elsewhere. A September 1963 mission had returned photographs of the gaseous diffusion and thermal power plants at Lanzhou. The images allowed photointerpreters to conclude that a new wing, approximately 134 feet wide, was under construction at the diffusion plant, and a building that had been under construction during a previous overflight had been completed.80

That spring Lop Nur was added to the list of U-2 targets, one of several secret operations directed against Chinese missile and nuclear activities conducted in concert with the Indian government. In 1962, to aid India in its conflict with China, the CIA had provided India U-2 photographs of the Chinese border. The next year the agency suggested establishing a temporary U-2 detachment in India, which would permit missions to be conducted against Lop Nur and other targets in Xinjiang. In the spring of 1964, India agreed to the secret deployment of a U-2 detachment at Charbatia, an old wartime base on the country’s east coast. Two or three missions followed, with the United States obtaining images of Lop Nur and India receiving current intelligence on Chinese deployments along its border. Of course, it was an arrangement that India, which prized its “nonaligned” status, sought to conceal. In May, after a mission over Xinjiang, the brakes on the returning U-2 failed and it rolled off the end of the runway. Out of fear of public disclosure, members of the Indian Aviation Research Centre, responsible for India’s aerial reconnaissance programs, “manhandled” the aircraft into a hangar until U.S. technicians could repair it.81

There had also been seven successful Corona missions between the publication of the July 1963 estimate and mid-July 1964. One mission carried a KH-4 camera, while the other six carried the improved KH-4A. The 4A camera was a stereo system with a resolution of between nine and twenty-five feet, and its images encompassed 1,440 nautical miles of territory. China was not, however, always adequately covered. James Q. Reber was the chairman of the Committee on Overhead Reconnaissance (COMOR), the interagency body responsible for deciding which targets would be photographed, when, and by what satellites or aircraft. In April he was informed by McCone’s deputy that McCone and deputy secretary of defense Cyrus Vance were interested in increasing the amount of Chinese territory covered in KH-4 missions, given delays in U-2 missions and the fact that the one successful KH-4 mission of 1964 had covered only one-fifth of China’s territory. Reber recommended to the National Reconnaissance Office (NRO) that more emphasis be given to China on the next satellite mission.82

In late July 1963 a satellite code-named Lanyard carrying a KH-6 camera with a resolution varying between four and six feet was successfully launched. While most of its targets were in the Soviet Union, at least one “spot in central China” was photographed. Imagery was also provided by the KH-7 Gambit satellites, ten of which were successfully orbited between July 1963 and the end of July 1964. A KH-7 mission in late April 1964 photographed Jiuquan and Baotou. The images from that mission were probably sharper than from the first missions, as the camera’s resolution continued to improve (to two feet by mid-1967).83

Overhead imagery played the key role in producing reports on what were first identified as a possible atomic energy complex in Jiuquan and a possible plutonium production facility at Baotou. The same could be said for Lop Nur, which was a target not only for U-2s, but also for Corona and Gambit satellites. Lop Nur was photographed during a February 1964 KH-4A mission, as well as during the late April 1964 KH-7 mission. While the February mission showed no apparent change from previous coverage, the April imagery revealed that a tower had been constructed at the site, the tower that would eventually host China’s first atomic bomb.84

The overhead photography allowed McCone to tell President Johnson on July 24 that the U-2s and satellites had observed five installations associated with the Chinese program “in various stages of assembly and operation.” That led the intelligence chief to conclude that the Chinese had overcome some, if not all, of the problems associated with the Soviet cutoff of aid. However, despite the intelligence effort devoted to monitoring the Chinese effort, McCone also informed Johnson that he could not “foretell when the Chinese would explode a device.” A three-page summary, apparently prepared for McCone’s presentation, stated that “evidence on Communist China’s nuclear weapons program is still insufficient to permit confident conclusions as to the likelihood of Chinese Communist detonation in the next few months. . . . We believe that Communist China’s leaders are determined to set off a nuclear device at the earliest possible moment in order to secure military, psychological, and political advantages.”85

Before the end of August the intelligence community would address the issue of “when” in a new estimate. That month, the photointerpreters at NPIC also completed a study, largely based on overhead imagery, of the suspect Jiuquan complex. The seven-page report consisted of text, images, and drawings based on the imagery. It described the complex as including a production area, thermal power plant, a workshop area, a main housing, as well as other facilities. It also noted that successive photographs showed expansion of the complex, and resulted in its December 1963 characterization as a “suspect” atomic energy complex being changed to “probable.”86

Beyond identifying the components of the complex, the interpreters provided details, including measurements of the components at Jiuquan and how they had expanded over the years. The interpreters also noted the apparent similarity between some of the reactor buildings at Kyshtym and a “probable” reactor building at the complex. Such caveats were often used in the report. One sentence referred to “one possible reactor building completed, a large probable reactor building under construction, and a possible chemical separation plant.”87

Such uncertainty about Jiuquan and the other components of the Chinese atomic weapons program, McCone and Johnson certainly hoped, would be reduced as the United States continued its intelligence campaign against those targets. Part of that effort included the August 5 launch of a Corona satellite carrying a KH-4A camera. On August 9, the satellite ejected one of its two recovery capsules, containing four days’ worth of imagery. While the plane that was supposed to snatch the capsule out of the air near Hawaii missed, frogmen were able to fish the valuable photographs out of the Pacific.88

The images contained in the capsule included photographs of the chemical and plutonium facilities at Jiuquan as well as of Lop Nur. The interpretation of those photographs led the CIA experts on China’s nuclear program in the OSI to conclude that “the previously suspect facility” at Lop Nur “is a nuclear test site which could be ready for use in about two months.” That judgment was part of a August 26 special national intelligence estimate, The Chances of an Imminent Communist Chinese Nuclear Explosion, which directly confronted the issue of “when.”89

While the analysts were now convinced that Lop Nur was “almost certainly” a test site that could be in used in two months, they believed that detonation “will not occur until sometime after the end of 1964.” That conclusion was driven by what would prove to be another faulty assumption: that China “will not have sufficient fissionable material for a test of a nuclear device in the next few months.” Their conviction resulted from the continued belief that China’s first bomb would be fueled by plutonium, not uranium (the Lanzhou plant, which had already produced the required U-235, was described as “behind schedule”), and that only one plutonium reactor—believed to be at Baotou—could not produce enough plutonium for a bomb until at least 1965.90

The intelligence analysts also believed that even if there were no major obstacles, it would take at least eighteen months, and more likely twenty-four, after the startup of the Baotou reactor before a nuclear device would be ready for testing. The earliest date that the Chinese could test, given these assumptions, would be mid-1965.91

The estimators raised the possibility that China might have another source of fissionable material. One option would be a facility started with Soviet help, prior to its withdrawal of assistance, at about the same time as work on the Lanzhou gaseous diffusion facility began. If it existed, overhead imagery had not yet identified it.92

Intelligence analysts also mentioned the possibility that China might have acquired fissionable material from a “non-Soviet foreign source”: France. A year earlier, on August 15, 1963, a State Department cable referred to indications of “French-Soviet and French-Chinese cooperation in the atomic energy field prior to the withdrawal of Soviet technicians from Communist China.” It also noted a continuing personal relationship between the high commissioner of the French Atomic Energy Agency and several members of China’s Institute of Atomic Energy.93

The analysts were also unsure what the activity at the test site signified. They noted the incongruity of bringing the site to a state of readiness without having a device nearly ready for testing, since it was technically unwise to install much of the instrumentation more than a few weeks before an actual test. However, they also observed that uneven progress in various phases of the Chinese program would not be surprising. In addition, given Lop Nur’s remote location and the poor transportation available, China might need a long lead time to prepare the installation. On balance then, the estimators believed that the detonation would not occur until at least early 1965.94

Such conclusions were disputed within and outside the intelligence community. Two prominent nuclear advisers and brothers, Albert and Richard Latter, told the CIA’s deputy director for science and technology, Bud Wheelon, that the CIA’s Office of Scientific Intelligence, which had responsibility for studying foreign nuclear programs, was “screwing up” in assuming that a first bomb would rely on plutonium. OSI chief Donald Chamberlain, a chemical engineer who had left his professor’s position at Washington University in St. Louis to join the agency, had misjudged the Chinese program and “got stubborn about it,” Wheelon recalls. He took the Latters to see McCone, who listened to their complaints.95

Allen Whiting argued that a test was imminent, doubting that the Chinese would put up the tower at Lop Nur, discovered in Corona imagery, unless they were planning a test. The agent reports of Zhou’s statements about a nuclear test in October further convinced Whiting that the CIA estimates were too cautious. That evidence, along with the public and private statements of Chinese leaders, led him to recommend to INR director Thomas Hughes that the United States invoke a contingency plan by announcing the upcoming test before the Chinese did, in an effort to lessen the impact and “reassure neighboring countries that the United States was watching and aware.”96

WITH THEIR ESTIMATE under scrutiny, CIA analysts began to restudy the data. At the same time, some U.S. officials were still thinking about military options or at least threatening to use force. On September 4, 1964, assistant secretary of state William Bundy suggested to his staff the possibility that a speech by Rusk could include a suggestion that Washington might take preventive action against Chinese nuclear facilities. Bundy’s proposal quickly produced opposition from Robert Johnson, who reasoned that any advance warning could help the Chinese blunt an attack, and would have a negative political impact internationally—by stirring fears of war while providing Beijing with a justification for its nuclear weapons program.97

How Bundy responded to Johnson’s advice is not known, but the seemingly imminent Chinese test made the question of preventive action ripe for a presidential decision. The Chinese nuclear danger had been discussed that summer at several of President Johnson’s Tuesday lunchtime meetings of his top national security officials. On September 15 critically important decisions were made. McCone, McNamara, Rusk, and McGeorge Bundy met in Rusk’s dining room at the State Department. Three days earlier McCone, again ahead of his analysts, had told Rusk that activity at Lop Nur and certain clandestine reports indicated that a test was imminent. Rusk then informed McCone that Soviet ambassador Anatoli Dobrynin had told former U.S. ambassador to the Soviet Union Llewellyn Thompson the same thing.98

On September 15 they decided that it would be better to let the Chinese test occur than to take “unprovoked unilateral U.S. military action.” Attacks on Chinese nuclear facilities would be possible only in the event of “military hostilities.” Although cautious on unilateral action, the advisers were sufficiently worried about Beijing’s nuclear progress to consider the possibility of joint steps with the Soviets, such as a warning to the Chinese not to test, or “even a possible agreement to cooperate in preventive military action.” Whether anyone at the table expected the Soviets to be any more receptive than they had been in 1963 is unknown. In any event, Rusk was to make early contact with Ambassador Dobrynin.99

McCone suggested the need for further information on developments at Lop Nur, and recommended that the president be asked to approve a U-2 overflight of the test site. The CIA director met initial resistance from Johnson’s senior advisers. For his part, Rusk noted that he knew a Chinese test was inevitable and he could not think of any action he would take if he was informed of the precise timing. McCone suggested that advance notice could be the basis for contacts with the Soviets as well as U.S. allies in Europe and Asia. But the general view was that the embarrassment and consequences of a failed mission outweighed any potential benefits. Neither Rusk nor Bundy would recommend the flight.. Before the day was out, however, McCone promised a mission with a greater chance of success, one that flew from Ban Takhli in Thailand to Lop Nur and back, and it gained the approval of the president’s advisers and Johnson himself.100

THE TAKHLI–LOP NUR U-2 mission was canceled sometime in late September or early October, because, as Thomas Hughes, the INR director at the time, observed, “nobody wants a U-2 shot down in the middle of a political campaign”—a consideration that, Hughes remembers, resulted in “a bewildered reaction of [the] collectors [at the United States Intelligence Board] at what politicians might do next.” Also influencing the decision to cancel was data obtained from a September satellite mission.101

Only the Soviet archives can confirm if Rusk met Dobrynin to discuss a joint approach; if they did, no U.S. records of the talks survived. But on September 25 McGeorge Bundy attempted to sound out the ambassador. A statement that Khrushchev had made on September 15, the same day that Johnson and his advisers discussed the Chinese nuclear problem, may have encouraged Bundy to believe that Moscow might be in the mood to consider joint action. Responding to Mao’s hostile comments about Soviet border rights in the Far East, Khrushchev warned that the Soviets would use all “means at their disposal” to protect their borders, including “up-to-date weapons of annihilation.”102

Despite Khrushchev’s tough talk, Dobrynin was not interested in discussing any anti-Chinese initiatives with Bundy. Just as in May 1963, Bundy proposed a “private and serious talk about what to do about this problem.” In response, Dobrynin admitted the “depth and strength” of the Sino-Soviet split, which he blamed on Mao’s “personal megalomania,” but he took a Chinese nuclear capability for “granted.” Chinese nuclear weapons, he argued, had “no importance against the Soviet Union or against the U.S.” A Chinese test would have a “psychological impact” in Asia, but that was of “no importance for his government.”103

The Soviet government’s negative response effectively settled the argument over direct action. The presidential election, only weeks away, undoubtedly had some impact on Johnson’s thinking. In the heat of the campaign, with Johnson running on a “peace platform” against the hawkish Barry Gold-water, the last thing he wanted to contemplate was any military action against China, with all of the risks involved. Whether election concerns were a bottom-line consideration, however, is an imponderable.

Johnson’s determination to avoid confrontation with China was made evident in his Vietnam policy, and very likely shaped his stance on preemption. Although he worried that inaction on Vietnam would benefit China, Johnson wanted to avoid military measures that might lead to a wider war. Even if Johnson had been less concerned with China’s reaction and leaned toward preemption, he would have had to face significant doubts about the feasibility of stopping the Chinese bomb by overt or covert action. Airstrikes would have required hitting facilities deep in the Chinese interior, requiring U.S. aircraft to “run the gauntlet of China’s air defense network” with less than complete information about that network’s disposition and capabilities.104 Even more important, “less than complete information” also described U.S. knowledge about China’s nuclear program. Neither John McCone nor anyone else in the U.S. intelligence community could have even come close to giving Johnson assurances that they could tell pilots or commandos exactly what targets had to be destroyed to prevent a Chinese nuclear test.

AROUND THE TIME of the Bundy-Dobrynin meeting on September 25, the U.S. intelligence establishment, probably relying on KH-7 images of Lop Nur taken in mid-August and KH-4A images from mid-September, decided that the preparations at the Lop Nur site were basically complete. Also suggestive was an agent report from a member of the Malian government delegation that had recently visited China; it stated that the Chinese had scheduled a test for October 1, China’s national day.105

By late September the White House and the State Department were ready to make an announcement. After Whiting indirectly leaked word of a Chinese test to CBS News, on September 29, reporters queried State Department spokesman Robert McCloskey about the accuracy of television reports of an impending test. With President Johnson’s consent, Secretary of State Rusk had already approved a statement for the press, which McCloskey read. He stated—for background only and not for attribution—that “from a variety of sources, we know that it is quite possible that [an] explosion could occur at any time.” Downplaying the event’s immediate significance, he observed that the Chinese were a “long way” from having nuclear delivery systems.106

The importance of intense satellite coverage was emphasized in a “Top Secret” October 2 COMOR memo, which noted that “the most pressing Chi Com intelligence problem . . . will concern the Chinese nuclear program,” and that “most of our knowledge of Chinese progress in the nuclear field has been derived from satellite photography.” Searching for additional facilities and monitoring known ones would require continued use of Corona and Gambit satellites. The high priority assigned to covering the Chinese nuclear program and the new Soviet missile silos had led the U.S. Intelligence Board to request that the NRO be prepared to double the number of Corona and Gambit launches over the following three months, so that possibly up to six KH-4A and four KH-7 cameras would be orbiting the earth during the year.107