SHORTLY AFTER 11:00 A.M. on March 3, 1991, Lt. Gen. Sultan Hashim Ahmad and Lt. Gen. Salah Abud Mahmud arrived in Safwan, just north of the border with Kuwait, to meet with Gen. Norman Schwarzkopf, commander in chief of the U.S. Central Command. Ahmad was the deputy chief of staff of the Iraqi Ministry of Defense, while Mahmud had been commander of Iraq’s recently decimated III Corps. Both of them “to Western eyes bore extraordinary resemblances to Saddam Hussein, with their black berets, dark olive uniforms, and heavy black mustaches,” recalled Gen. Sir Peter de la Billiere, the British deputy commander of the coalition forces.1

Three days earlier, President George H. W. Bush declared a cease-fire in the Persian Gulf War after the allied forces led by Schwarzkopf had routed Iraqi forces, first driving them out of Kuwait and then back toward Baghdad. When NBC anchorman Tom Brokaw asked Schwarzkopf what he planned to negotiate with the Iraqis, the general snapped, “This isn’t a negotiation. I don’t plan to give them anything. I’m here to tell them exactly what we expect them to do.”2

A day earlier the UN Security Council passed the first of ten 1991 postwar resolutions telling Saddam Hussein’s regime what it expected now that his army had been defeated. The second of those resolutions, passed by a twelve-to-one vote on April 2, with only Cuba voting no, consisted of thirty-four points, including the demand that Iraq “unconditionally accept the destruction, removal, or rendering harmless, under international supervision of all chemical and biological weapons and all stocks of agents; and all related subsystems and components of all research, development, support and manufacturing facilities.” Ballistic missiles with a range greater than 150 kilometers (93 miles), along with related major parts and repair and production facilities were also to be destroyed.3

Intending to make a clean sweep of Iraq’s ability to produce and deploy weapons of mass destruction, the Security Council ordered Saddam’s regime not to obtain or develop nuclear weapons or nuclear weapons–usable material or “any subsystems or components or any research, development, support or manufacturing facilities” involved in producing such weapons or weapons-usable material. Iraq was also ordered to provide the UN secretary general and the director general of the International Atomic Energy Agency, within fifteen days, with a declaration that fully disclosed Iraq’s nuclear weapons facilities and material.4

Further, Iraq was also to place any weapons-usable material under the control of the IAEA. In addition, it “requested” that the IAEA director general, Hans Blix, carry out “immediate on-site inspections of Iraq’s nuclear capabilities based on Iraq’s declarations and the designation of any additional locations by the [U.N. Special Commission on Iraq—UNSCOM].” The atomic energy agency was also requested to develop a plan, within forty-five days, for the “destruction, removal, or rendering harmless” of all the nuclear weapons–related material prohibited by the resolution.5

Assigning the IAEA to investigate Iraq’s progress toward an atomic bomb and destruction of weapons-related material came only after a diplomatic dispute between the United States and Britain on one side and France on the other. The first Anglo-American draft of the April 2 resolution gave the unit that would become known as UNSCOM the responsibility for disarming Iraq of all weapons of mass destruction. The IAEA had been created primarily to advance the peaceful uses of atomic energy. Nuclear weapons states provided nuclear technology to be used for peaceful purposes and the IAEA, through consensual “safeguards inspections,” accounted for weapons-grade uranium and plutonium. The agency’s legacy did not lie in overcoming denial and deception. Its failure prior to the Gulf War to notice Iraq’s huge nuclear weapons effort—despite direct and repeated access to Tuwaitha because Iraq was a signatory to the nonproliferation treaty—left certain members of the Bush administration deeply skeptical of the agency’s ability to carry out the nuclear disarmament mission.6

One problem, according to former IAEA inspector David Kay, was that the agency’s technical personnel had no weapons background. In the case of Tuwaitha, they had been easily misled, being shown portions of only three of the hundred buildings at the site. The facility was cleverly laid out, including the distribution of buildings and the use of trees to provide visual screening. The clever routing of the site’s internal road system made it very difficult for any outsider, Kay recalled, “without access to overhead intelligence to accurately understand the size of the center and the relationship of the buildings to each other.” The agency’s deputy director general for technical assistance, who had never seen any overhead images of the site, had no idea how much his inspectors were not being shown. Not surprisingly, the inspectors never asked about the rest of the site or for permission to see it. But the IAEA supporters in the Bush administration argued that to refuse to assign the agency the inspection mission would fatally cripple it at a particularly inopportune time—right before the conference reviewing the nonproliferation treaty, a treaty that the IAEA played a crucial role in enforcing. The IAEA supporters won out and the IAEA was assigned the nuclear disarmament role in the April 2 resolution, while UNSCOM was given the mission of verifying Iraqi compliance with regard to all other varieties of weapons of mass destruction.7

IN EARLY MAY a letter from the UN secretary general, Javier Perez de Cuellar, was delivered to the Iraqi foreign minister, spelling out the rights of the UNSCOM teams that would be arriving in Iraq to inventory and destroy Iraqi chemical, biological, and missile facilities and weapons. Those rights would soon be extended to the IAEA teams investigating Iraqi nuclear programs. There were to be no restrictions on their movements in and out of Iraq, no interference with their access to any site or facility designated for inspection, no attempt to prevent interviews with relevant personnel, and no restrictions on communications, whether by radio, satellite, or mail. In addition, Iraq was obligated to provide requested documents relevant to disarmament, which the teams could examine and copy. The teams also would have the right to use aircraft to photograph facilities and activities and to take and analyze samples of any kind.8

There were obvious parallels between the UNSCOM and IAEA teams and the Alsos effort at the end of World War II—the mandate to investigate efforts of a defeated enemy to develop weapons of mass destruction and virtually free reign to accomplish that mission. And the United States would have access to the product of their efforts. There were also important differences. Alsos had been strictly a U.S.-conceived and -directed effort, with some British participation. The UN teams in Iraq included scientists from nations such as France and Russia, while the Alsos teams had tried to prevent French and Russian scientists from acquiring information about the German effort or getting their hands on German scientists.

More importantly, the Allies had occupied all of Germany in 1945. There was no surviving German government that sought to interfere with their activities. In 1991 the United States and its allies occupied only the southern portion of Iraq, while Saddam remained in power. In 1993 he established the National Monitoring Directorate, ostensibly to handle Iraqi government dealings with the inspection teams, but as part of the Iraqi objective to make the teams work as unproductive as possible. From 1991 each of the regime’s numerous intelligence services was involved in the concealment effort, with the Special Security Organization, headed by Saddam’s son Qusay Hussein, coordinating their efforts. Qusay also headed the Concealment Operations Committee, established in May 1991. The Special Republican Guard and the Military Industrialization Commission were part of the concealment effort too.9

The first of the IAEA inspections began in May 1991. The Iraqi declaration of April 19 was of no help. Signed by Saddam himself, it claimed that Iraq possessed no nuclear materials covered by the resolution. It was amended on April 27 to acknowledge Iraq’s possession of additional nuclear material and facilities, including a “peaceful” research program, with headquarters at the Tuwaitha Nuclear Research Center—still far from the truth. When the inspectors did find documents, they would be faced with the “multiple, constantly shifting, and overlapping codes for individual components” that Iraq had employed for all its weapons programs.10

The inspectors, in preparation for their first inspection, would also have very limited help from the U.S. intelligence community, which professed to have little specific knowledge of the Iraqi nuclear weapons effort and nothing like a comprehensive overview. There had been no systematic overhead imagery of central Iraq. Among the items missed by the United States and other nations was Iraq’s acquisition of soft iron magnets for its calutrons, which were purchased from an Austrian firm, shipped through Hamburg, and trucked across Turkey. It was the type of activity easily detected in Hollywood films—where the United States has an ever-present eavesdropping capability and operates spy satellites that can constantly track trains, cars, and other vehicles—but not in the real world.11

On May 14 a Romanian BAC-111 aircraft landed at Saddam International Airport carrying thirty-four specialists in physics, chemistry, and nuclear engineering. Inspections began the next day and lasted until May 21. The team arrived equipped with a variety of detection gear, prepared to measure the gamma rays given off by uranium samples, to identify uranium enrichment efforts, as well as to detect the Cerenkov glow emitted by high-speed electrons, which when viewed through night-vision devices can reveal whether the plutonium in spent fuel rods is still there or has been removed to make bombs. The team was also prepared to sample vegetation, take smear samples from building walls, and analyze the soil—all for signs of illicit nuclear activity.12

The IAEA1 team, headed by veteran IAEA inspector Dimitri Perricos, spent most of its time exploring the huge nuclear research facility at Tuwaitha, which had some buildings destroyed by coalition bombing. Before the inspectors arrived, Iraq added to the destruction, leveling the large calutron test facility and covering it with dirt, as well as destroying the laser and centrifuge test facilities at the site. The inspectors were, however, able to accomplish their key objective and locate the enriched uranium believed to be at the site. What they were not expecting to find were the 2.26 grams of plutonium that turned up during their search.13

The inspectors also sorted through the rubble at Tarmiya. Iraqi army officers stationed there claimed that one facility, which appeared to be a factory, had produced electrical transformers—although the plant was too large and complex to be a simple manufacturing site. “We were perplexed by the building setup,” Perricos recalled. “If this was for the manufacture of transformers there were too many buildings, too much chemistry.” A Western intelligence service had suggested that it might have housed centrifuges, but the team found no evidence of their presence. The pictures of the facility’s layout did remind some of a more primitive form of uranium enrichment—World War II–era calutrons.14

There were early indications that Iraq was going to be less than fully cooperative. It was apparent to the team that Iraq had conducted, as former UNSCOM inspector Tim Trevan recalled, “extensive clearing operations before the inspection to remove much of the equipment that had been at al-Tuwaitha.” The Iraqis neither declared the equipment nor would reveal its current location. While some of the relocated equipment was shown to the inspectors, other items remained hidden.15

It did not take long before Iraqi interference with the nuclear inspectors became more blatant. The second IAEA inspection team was led by David Kay, a fifty-one-year-old Texan with a doctorate in international affairs from Columbia University who had worked in the Pentagon before joining the IAEA in 1983. Like Perricos, he was a veteran of many IAEA safeguards inspections. But in contrast to Perricos’s good cop, Kay would often play the bad cop in dealing with the Iraqis. Mahdi Obeidi recalls that Kay “had a brash confrontational style. He rode around Iraq, acting like a cowboy on big horse, and over time all the scientists became afraid he would expose their former work.” Also in contrast to the first inspection team, Kay’s would be armed with some significant intelligence from the United States, including a fact revealed by satellite images—that immediately after the inspection at Tuwaitha, the Iraqis had uncovered and removed disc-shaped objects that had been buried outside of Tuwaitha.16

Initial analysis of the photographs by IAEA as well as U.S. analysts left both groups puzzled about the intended use of the large cylindrical objects on the trucks. A suggestion that the equipment in the images were calutrons was initially dismissed, in the belief that the Iraqis would not attempt to enrich uranium using antiquated World War II technology that required huge expenditures of money and energy. Earlier suggestions from one or more analysts at either Los Alamos or Sandia (or both) that Iraq might be employing calutrons had been rejected at higher levels of the Energy Department. IAEA head Blix, and his deputy, Mohamed ElBaradei, were among the doubters. But John Googin, a retired nuclear weapons engineer and veteran of Oak Ridge and the Manhattan Project, when shown the images had no trouble in confirming that the inspectors and the satellites had indeed photographed calutrons.17

Kay’s team arrived in Baghdad on Saturday, June 22, armed with intelligence provided, via the United States, from two Iraqi engineers who had fled west and were familiar with Iraq’s nuclear weapons program. In addition, the team knew that U.S. intelligence had been able to track suspicious objects (the calutrons) from Tarmiya to the Abu Ghraib military barracks near Baghdad, a site not mentioned in Iraq’s declarations concerning its weapons of mass destruction activities. On June 23 the IAEA2 team showed up at the barracks, ready to conduct a surprise inspection and demanding full access.18

Despite Iraq’s claim that it had nothing to hide, Iraqi soldiers blocked the entrance to the site that Sunday. The attempt was not a total loss, however. From their positions outside the barracks, inspectors could see, and used tele-photo lenses to photograph, trucks, cranes, and a forklift moving out heavy, draped objects—the calutrons that the U.S. intelligence community had tracked from Tarmiya to Abu Ghraib. Kay’s team tried again on Tuesday and was again denied admittance. It was only on the third try, the following day, that the team was let in—but by then all the incriminating evidence was gone. IAEA chief Blix noted that there was “no longer any trace of the activities and objects” his inspectors had seen a few days earlier.19

The day after the team’s futile return visit to Abu Ghraib, the fifteen permanent representatives of the UN Security Council, Secretary General de Cuellar, and two senior UN officials were shown photos obtained by one or more KH-11 satellites. The United States wanted it to be clear that the failure to find anything there was due to Iraqi duplicity not Iraqi compliance. The secret images showed uncrated calutrons being moved onto trucks just before inspectors arrived at Tuwaitha, Tarmiya, and Abu Ghraib.20

The inspectors faced interference again on June 28, when Kay and his team arrived in Fallujah, intent on exploring the Military Transportation Facility, based on a tip from the CIA. The agency’s information indicated that the regime had collected various items from its nuclear program at the site. Satellite photographs had shown the facility’s buildings, a fenced perimeter, a water tower outside the fence, and a single front gate. Other intelligence, probably another set of photos, indicated the calutrons had been moved, from Abu Ghraib to Fallujah.21

The convoy of vehicles arrived at the transportation facility carrying the inspectors, their equipment, and their “minders”—Iraqi officials whose ostensible mission was to serve as guides and liaisons between the inspectors and their targets but were not supposed to know in advance what site was to be inspected. Kay then told the chief minder that he wanted to inspect the site, and reminded him that while his team was waiting to enter, only UN vehicles should enter or leave the site, and no equipment was to be moved. Kay also sent some of the inspectors to watch the exits, and one of “Kay’s cowboys”—as Robert Gallucci characterized them—climbed a nearby water tower, which allowed him to monitor the entire site.22

It came as no surprise that the Iraqis tried to deny the team access. In the midst of his telling the Iraqis what was required of them, Kay received a call over portable radio from the inspector perched in the water tower. The bomb-making equipment that the U.S. intelligence reports claimed was at the site, and Iraq denied possessing, was being loaded onto trucks that were getting ready to leave.23

Kay and his team could do nothing to gain entrance, because heavily armed soldiers blocked their way. But the inspectors stationed at the exits would be able to photograph the trucks when they departed. One, Rick Lally, had brought his own new and expensive camera. When the trucks left, he started snapping pictures, then jumped into a UN vehicle along with other inspectors and continued taking photos as the UN vehicle chased the trucks. The chase ended when an Iraqi vehicle drove the inspectors’ car off the road. The Iraqis then tried to force Lally, at gunpoint, to turn over the camera and film—a demand he successfully deflected, having hidden the film and claiming that the device was actually a new type of binoculars.24

The inspectors’ photographs were not the only images demonstrating that the Iraqis were willing to make a great effort to hide the equipment stored at the military transportation facility. Another set came, not from ground level or from the perspective of a water tower, but from outer space, as one or more of the National Reconnaissance Office’s constellation of imagery satellites recorded the Iraqi convoy driving away from Kay and his inspectors. Not surprisingly, the convoy was out of view of the satellites before it reached its destination, but the images obtained by the inspectors and satellites revealed new information about Iraq’s nuclear weapons program.25

The consolidated report on the first two IAEA inspections provided the U.S. intelligence community with data, unobtainable prior to the war, on the inner workings of Tuwaitha. It also assessed how effective the coalition aerial attacks had been in destroying or disrupting the facilities at the nuclear center. It described the status of the research reactors, the hot cells, a variety of laboratories, and the chemistry and chemical engineering building—while the laboratory and workshop building was totally destroyed, all three compartments of the hot cells in the radiochemistry laboratories were intact. The report also evaluated the overall development of the Iraqi program, with a description of the findings during the first team’s inspection of the Tarmiya complex, which it labeled as a “possible nuclear facility,” as well as its examination of several other sites suspected of fabricating calutron components.26

The Iraqi actions of late June, which included firing over the heads of one group of inspectors on June 28 as they followed the convoy out of Fallujah, produced sharp reactions from the United States and UN. The international body sent a high-level delegation, which included UNSCOM chief Rolf Ekeus as delegation head, the IAEA’s Blix, and Yasushi Akashi, the UN’s undersecretary general for disarmament affairs. They met with Iraqi foreign minister Ahmed Hussein on June 30 and with deputy prime minister Tariq Aziz the following day. The message they conveyed, backed up by serious U.S. preparations for military action, led to a July 5 letter from Saddam to the UN secretary general, promising compliance and a new list of nuclear-related items that would be of interest to the inspectors.27

After Kay’s team left Iraq on July 3, a new IAEA team arrived, with Dimitri Perricos at the head of the thirty-seven inspectors. Early in their visit they were escorted into a large conference room at the Al Monsour Hotel, where they met with a collection of Iraqi nuclear experts. The experts appeared uncertain about what they could say when suddenly, according to Cal Wood, a Livermore physicist, a “well-dressed man in the back, in impeccable English with a British accent, said ‘I will answer all your questions.’” The man was Jaffar Dhia Jaffar, who inspectors and U.S. intelligence knew held a senior position in the Iraqi nuclear program, but who had not yet realized he was Iraq’s J. Robert Oppenheimer.28

Jaffar acknowledged that the Iraqis had made some progress in the field of uranium enrichment, and even arranged for visits to sites where Iraqis had destroyed or concealed calutrons. Inspectors visited seven desert sites and found thirty magnets. They also heard explanations of how the Iraqis had tried to blow up some of the calutrons, but accomplished nothing more than lifting them up off the ground, only to have them land undamaged.29

Jaffar claimed, however, that the enrichment effort did not have a military objective, that there was no plan to use the highly enriched uranium for nuclear weapons. The objective, he said, was to provide fuel for research reactors and a future nuclear power program—an assertion the inspectors considered implausible given the existence of two types of equipment used for separation, one with low capacity and high-separation ability and another with high capacity and low-separation capability.30

As part of Iraq’s limited disclosure, the Perricos team was shown a video of the February 1990 inauguration of the Tarmiya plant. The video, along with blueprints of the plant, allowed the inspection team to calculate that the facility could produce up to thirty-three pounds of 93 percent enriched uranium each year. They also concluded that Ash Sharqat, which was 85 percent complete at the beginning of the war, was a duplicate of Tarmiya, and not a factory for the plastic coating of equipment as Iraq claimed. Together the facilities would produce enough highly enriched uranium for two nuclear bombs a year.31

By the time they had completed their inspection on July 18, Perricos’s team was convinced that they had seen only part of a full-scale nuclear program, and that the enrichment programs, particularly the gas centrifuge technique, had been more advanced than Iraq was willing to admit. They also believed that a substantial effort would be required to track down all the items that had been transferred from Tuwaitha, Tarmiya, and Ash Sharqat.32

The Iraqis had made a significant effort to hide the true nature of Tarmiya and Ash Sharqat from the inspectors. In addition to removing key equipment from the facilities, they had also tried to cover up telltale signs of the original layout, including rails and return irons for the separators, by laying down a new cement floor at each site.33

At the time the third IAEA inspection was winding down, David Kay and his team were preparing to build on their work. IAEA4 would seek to uncover more about the centrifuge enrichment program, to produce a detailed evaluation of the calutron effort, and to search for evidence of weaponization facilities. The team’s arrival in Baghdad, on July 27, had been delayed a day because President Bush was threatening military action against Iraq unless the country revealed the full extent of its nuclear weapons program. The team arrived with orders to report its location to UNSCOM in New York at three-hour intervals to ensure that if the United States did undertake military operations, team members would not become unintended casualties.34

On the first morning, the Iraqis revealed more about their nuclear activities, which made it clear that they had conducted a covert program to produce natural-uranium fuel elements from nuclear materials the Iraqi government had not, as it was obligated to, disclosed to the IAEA under the Safeguards Agreement. In addition, two experiments conducted at Tuwaitha’s Experimental Reactor Fuel Fabrication Laboratory were intended to produce fuel elements containing plutonium. The center of the experiments was the IRT-5000 reactor core. Despite two IAEA inspections each year, the experiments had not been detected, apparently because Iraq had removed the experimental fuel elements before each inspection.35

Kay’s group conducted a no-notice inspection of the Mosul Production Facility at Al Jazirah, which uncovered its true mission, the production of uranium hexafluoride to be used in gas centrifuges—although the building for uranium hexafluoride production had been leveled. They also visited the Al Furat complex, which Iraq admitted had been built to produce gas centrifuges. The plans for Al Furat, according to Iraqi authorities, spanned another five years. The construction and operation of the centrifuge production plant was to be completed by the end of 1991, while the first 100-machine cascade was to be in operation by mid-1993. By early 1996 a 500-machine cascade was to be in operation. As much as fifty-five pounds of uranium, enriched to at least 90 percent U-235, would be produced each year.36

Al Atheer, suspected of having a connection with nuclear weaponization, was also on the team’s list. Jaffar had claimed that no official decision had been taken to develop nuclear weapons, and that any design activities “had been only individual exercises by interested scientists.” After visiting the site, Kay and his team came to a different assessment. The unit’s report noted that “one of the most visible weaponisation activities is high explosive testing,” and the existence of a firing bunker belonging to the Hatheen Establishment of Al Musayyib and “now heavily damaged” near the Al Atheer materials research center. It also mentioned that the bunker had been used a few times for crude testing of conventional explosives and was “capable of supporting significant physics experiments critical to nuclear weapons development.” In addition, it reported that “some construction work is under way at this site despite the damage, and this suggests that such a facility has a very high priority.”37

After completing its work on August 10, Kay’s team prepared a report for the UN Security Council, which stated that “Al Atheer and its companion facilities at al-Hateen and al-Musayyib constitute a complete and sufficient potential nuclear weapons laboratory and production facility within one common fence line. This combined facility is so big and well equipped that it can clearly do much more than the limited non-weapons activities that the Iraqis claim as its purpose. It is certainly a top candidate for future monitoring.”38

A direct consequence of the new evidence of Iraq’s nuclear weapons ambitions was a new UN resolution, 707, adopted on August 15. It was, according to former UNSCOM inspector Tim Trevan, the “strongest outpouring of vitriol and bile in the history of the U.N.” The resolution, which even Cuba supported, condemned “Iraq’s serious violation of a number of its obligations under . . . resolution 687 (1991) and of its undertakings to cooperate with the Special Commission and the IAEA.” Those failures represented, the Security Council declared, “a material breach of the . . . resolution . . . which established a cease-fire.” The resolution also demanded that Iraq immediately halt any attempts to conceal movement or destruction of equipment relating to its weapons of mass destruction programs without consent from the UN, make available any previously denied equipment, and permit overflights throughout Iraq for a variety of purposes, including inspection and surveillance.39

Passage of the resolution was followed by a U.S. offer to fly U-2 missions over Iraq, an offer accepted by Ekeus, with the understanding that the missions, which would be designated Olive Branch, would be under his control. But the first two post-overflight briefings were not well received. The United States provided a limited number of photographs that had been degraded to conceal the U-2 camera’s capability, and were delivered weeks after the mission was completed. The photos provided no information about the time they were taken or the longitude and latitude of the target, information normally imprinted on U-2 images. The second briefing, held in Ekeus’s office on the thirty-first floor of UN headquarters in New York and attended by intelligence analysts, some senior U.S. Air Force officers, and U.S. ambassador to the UN Thomas Pickering, provoked an outburst from Ekeus. Reminding his guests that the U-2 missions were to be a UN operation, he asked what they had produced. It was a rhetorical question, and after providing his answer—a few lousy fuzzy photographs of no use to anyone—he tossed them in his garbage can.40

Ekeus’s complaints produced the desired results. At the third briefing, held soon after the next U-2 flight, the photographs were remarkably sharp and useful, and had the time stamped on them along with the name of the facility photographed. The United States also turned over negatives of the images shown at the briefing, which could be analyzed by the imagery interpreters that UNSCOM had recruited. The interpreters, along with the Information Assessment Unit established by Ekeus, provided the inspectors with their own independent interpretation and analysis capability.41

BY JUNE 1991, as result of defector debriefings, U.S. analysts believed they could pin down the exact location of key documents describing Iraq’s weaponization program. A proposal to blockade the building where the documents were believed to be while a search was conducted ran into initial opposition from Blix as well as Perricos, who were accustomed to consensual safeguards inspections. But the United States insisted that an IAEA inspection go forward, headed by Kay, or that the effort be conducted by UNSCOM. Blix reluctantly agreed.42

Kay’s team arrived on September 22 for what was to be the sixth inspection. Serving as his deputy was Robert Gallucci, who joined the UN effort in April, after having spent three years teaching at the National War College and then briefly rejoining the State Department to advise on the disarmament of Iraq. At 5:30 on the morning of September 23, Kay and his team of forty-four gathered in the lobby of the Rasheed Hotel, accompanied by their Iraqi minders, and headed for the multistory L-shaped Nuclear Design Center across the road—“arriving unannounced and in force, like cops on a drug bust,” according to Newsweek. Hoping to avoid alerting the Iraqis if they made a significant discovery, they had selected a set of code words to be used in their radio communications.43

After Kay’s team secured the building, the inspectors spread out to check each floor. The intelligence provided by the CIA indicated that the key documents could be found in a basement room in a building annex, leaving a significant area to be searched. At 10:00 a.m. Kay was on the eighth floor when a message containing the magic word came across his radio, indicating that the team had hit paydirt. The documents had been found in the basement, as the CIA had predicted. Since the elevators were out of commission, Kay trotted down the stairs. When he arrived in the basement, he found several trunks filled with documents, including a report from Al Atheer concerning the progress made on developing an implosion-type weapon up to May 1990.44

Kay’s first priority was to get the evidence out before the Iraqis discovered what his team had found. He took advantage of one American inspector’s stomach infection, which caused severe dehydration. Kay requested one of his medics to evacuate him, taking him directly to Habbaniyah air base, where a UNSCOM aircraft would take him to Bahrain. The plane also carried some of the documents, which Kay had hidden in the inspector’s jacket. The plane took off at two in the afternoon and reached Bahrain less than three hours later. By the end of the day copies of the documents had been faxed to the IAEA in Vienna and UNSCOM in New York.45

Finally, around 3:30 in the afternoon, the Iraqis tumbled to what was going on, and demanded that they be given a full inventory of the confiscated documents. Throughout, the inspectors had been making their own inventory and marking the relevant documents. Kay gave the order for the UNSCOM vehicles to be loaded with the trunks and transfer them back to the field office, but the Iraqi minders blocked the team’s departure. At 4:30 Iraqi officials arrived and began an inventory of the documents on the inspectors’ trucks. Jaffar, who the Al Atheer report identified as the leader of the weaponization program and deputy chairman of the Iraqi Atomic Energy Commission, also showed up and demanded a complete inventory. Kay had his own demand—that the team be allowed to leave at 6:30. Instead, at seven, the Iraqis confiscated the materials at gunpoint, an act photographed by the team. At two in the morning the Iraqi minders turned up to return the documents to Kay’s team, minus, a quick check of their inventory showed, all of the ones the inspectors considered relevant.46

Four hours later, Kay’s team gathered at the hotel again, prepared to pursue a lead from the Al Atheer report, and found themselves outnumbered by their minders by a three-to-one ratio. They loaded up the vehicles as if they were preparing for a major expedition, although they were planning on going only one hundred yards, to the headquarters of Petrochemical-3. By 6:20 they had arrived. They immediately discovered large quantities of relevant documents, which guaranteed that their Iraqi minders were unhappy from the start of the day. Kay instructed the team to load the documents onto their vehicles as soon as they were discovered, but at 10:50, the chief minder ordered all activity to stop. When the inspectors tried to ignore his orders, they were forcibly removed from the building. Kay, told to unload the documents from the vehicles and leave, responded that they were not leaving without the documents. At 12:30 Jaffar arrived and also demanded that the team return all the documents and films they had confiscated.47

Team members proceeded to circle their wagons in the parking lot—a Land Rover, a Toyota, and an old bus. That was the beginning of a four-day standoff in which the days were hot and the nights cold, as there was no cloud cover to prevent the temperature from rapidly falling after the sun went down. The inspectors’ diet consisted of watermelon and military Meals-Ready-to-Eat (MREs). In addition to eating and waiting, they also secretly transmitted some of the data they acquired to a satellite, which relayed it to a secret National Security Agency site in Bahrain.48

The Iraqi government organized demonstrations and made assorted accusations. Finally, on the afternoon of September 27, at UN headquarters in New York, an agreement was reached allowing the team to leave with the documents. Both sides would review and inventory the seized documents and films at the UNSCOM office in Baghdad, and Iraq would retain the inventory. Irrelevant documents would be returned to Iraq, but the final decision as to relevance would be Kay’s.49

On September 28, at 5:46 a.m. Baghdad time, the team was finally released. The inspectors then spent the entire day reviewing the sixty thousand or so documents they had brought back, which included a copy of the Al Atheer progress report. The next day UNSCOM’s support staff shipped documents out to Bahrain, while the team searched three further sites. Not surprisingly, whatever documents that had been there had already been cleaned out or destroyed—on the third day of the standoff, the team had seen smoke from a fire on the top floor of one of the two targeted buildings.50

The team’s report (which included the entire Al Atheer report as an annex) noted that it had “obtained conclusive evidence that the Government of Iraq had a program for developing an implosion-type nuclear weapon and it found documents linking this program to Iraq’s Ministry of Industry and Military Industrialisation, the Iraqi Atomic Energy Commission (IAEC) and the Iraqi Ministry of Defense.” It also informed the Security Council that “contrary to Iraq’s claims of having only a peaceful nuclear program, the team found documents showing that Iraq had been working on the revision of a nuclear weapon design and one linking the IAEC to work on a surface-to-surface missile project—presumably the intended delivery system for their nuclear weapon.”51

The documents revealed that Al Atheer was the center for nuclear weapons design work, despite Iraq’s declaration that it housed no nuclear activity of any sort, and that extensive weaponization work had also been conducted at Tuwaitha. Other documents revealed the existence of a project to produce a sizable amount of lithium-6, a key component for thermonuclear weapons (although ultimately it would be determined that only small quantities had been produced and little, if any, theoretical work had been done on hydrogen bomb development). They also established a link between Iraq’s work on gaseous diffusion and uranium enrichment techniques to the weapons effort. Further, the documents showed that Jaffar Dhia Jaffar, despite his claims that Iraq had not been trying to develop nuclear weapons, was one of the program’s senior officials. Indeed, the team finally concluded that Jaffar was the program’s director.52

THE INSPECTION of late September was David Kay’s (and Robert Gallucci’s) last for the IAEA. But over the next year, eight agency teams visited Iraq. The October and November 1991 teams supervised the destruction of uranium enrichment and processing equipment and removed stocks of irradiated nuclear fuel from the country. From April through July 1992 inspectors directed the destruction of equipment and facilities at Al Atheer, Tarmiya, and Ash Sharqat.53

On January 23, 1991, little over a week into the aerial campaign, and about a month before the ground war began, President Bush had reassured the nation that “our pinpoint attacks have put Saddam out of the nuclear bomb building business for a long time.” And on several occasions in late January, General Schwarzkopf said the coalition’s attacks “had destroyed all their nuclear manufacturing capability.”54

Those assertions were based on the assumption that the CIA and other key intelligence agencies had a good understanding of the Iraqi nuclear program—its size, scope, and progress—prior to the initiation of the air war. Over the course of 1991 the U.S. intelligence community would learn far more about the Iraqi nuclear program, in part from independent intelligence collection—overhead imagery, eavesdropping, and human intelligence (including the debriefing of defectors). But the UN inspections played a major role in transforming the intelligence collected into firm conclusions about the status of the Iraqi program before the war.

In late May 1991 four Iraqis drove up to a U.S. Marine checkpoint near Dohuk, a hamlet in northern Iraq that had been established to protect the Kurds. One occupant, who was accompanied by his wife, brother, and a friend, told one Marine, “I am Saddam Hussein’s top nuclear scientist.” He was whisked away for debriefing, along with his family and friend—taken first to Turkey and then to Munich.55

As was not unusual with defectors, he was exaggerating. He was not Jaffar Dhia Jaffar, but a physicist who had worked at the Ash Sharqat calutron facility. He disclosed the progress that Iraq had made in advancing the World War II–era technology, and claimed to know of several sites where such facilities existed. He also reported that the coalition bombing campaign had missed a number of key facilities, including a large underground uranium enrichment facility inside a mountain north of Mosul. In addition, he passed on some inaccurate hearsay—the assurances of a colleague that the Petrochemical-3 facility already had eighty-eight pounds of highly enriched uranium. He claimed that Saddam expected to have a bomb by the end of the year. The defector also reported that nuclear weapons material and equipment had been transferred to the substitute site before the beginning of the Gulf War, and provided information concerning Iraqi use of gas centrifuges and research on chemical high explosives to trigger nuclear detonations. One U.S. analyst characterized the defector as “the one guy, out of thousands, who came forward and who actually had useful information about Saddam’s nuclear program.”56

The defector’s report spurred even more extensive satellite imagery of Iraq, including Tuwaitha. Some of the images showed that after the inspectors left the facility on May 21, 1991, the Iraqis disinterred the disc-shaped objects that they had buried there—the objects Oak Ridge veteran John Googin was able to identify as calutrons.57

That defector was not the only Iraqi official to come forward with tales about the nuclear program. By September, according to one account, at least three Iraqi officials with extensive knowledge of the program had defected to allied intelligence agencies since the end of the war in February.58

By late September the accumulation of data from defectors, spy satellites, and UN inspections gave the U.S. intelligence community a far better grasp of the Iraqi nuclear weapons program, as well as its other weapons of mass destruction programs, than it had possessed at the beginning of the year. It was also the view of the IAEA that by that time despite the Iraqi government’s strategy of “obstruction and delay . . . to conceal the real nature of its nuclear projects . . . the essential components of the clandestine program have been identified.” A significant factor in the agency’s ability to accomplish that task, the IAEA noted, was “the provision of intelligence information” by its member states.59

Among the new insights was Iraq’s attempt to employ three different technologies to produce highly enriched uranium: electromagnetic isotope separation (calutrons), thermal diffusion, and gas centrifuges. In addition, a minute quantity of plutonium had been produced at Tuwaitha, by cheating on international safeguards. The extent to which Iraq had acquired a wide range of sophisticated and restricted nuclear weapons technologies, including carbon-fiber rotors used in gas centrifuges and super-hard maraging steel that could be used in centrifuges or a bomb itself, was understood for the first time.60

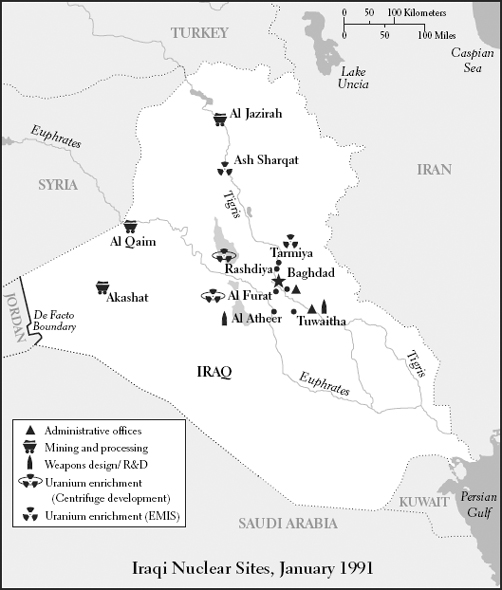

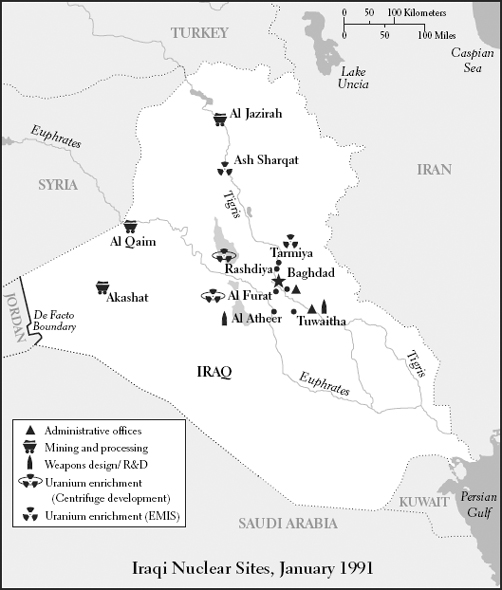

Related to the appreciation of the different technologies employed was the identification of all but one of the key facilities that made up the Iraqi program, along with their purpose. By the end of September 1991 the U.S. intelligence community understood that the prewar Iraqi program included facilities at Tuwaitha (Nuclear Research Center), Al Qaim (uranium concentration plant), Al Jazirah (manufacturing of uranium oxide and uranium tetrachloride for the EMIS program), Tarmiya (EMIS Plant), Ash Sharqat (EMIS plant), Al Atheer (Materials Center for nuclear weapons production and development), and Al Rabiyah (Manufacturing Plant with workshops designed and built for the manufacture of large metal components for the Iraqi EMIS program). Inspectors did show up at the Rashdiya centrifuge development center during the fourth IAEA inspection, based on a tip from a defector in the summer of 1991, and again in January 1992, but its true function would not be appreciated until much later.61*

Understanding virtually the full range of facilities and technologies that constituted the prewar Iraqi program brought with it an understanding of what the intelligence community had failed to discover about the Iraqi program: Al Atheer’s role in weapons design, Al Furat’s secret mission of building centrifuges, and the pursuit of electromagnetic separation to produce enriched uranium. Al Atheer was not linked to the nuclear program until a week before the war ended. Even then, the three buildings essential to any effort to assemble and test bomb components were not detected. The extent that the United States and its allies underestimated and misunderstood the Iraqi program constituted a “colossal international intelligence failure,” according to one Israeli expert. IAEA Hans Blix acknowledged that “there was suspicion certainly,” but “to see the enormity of it is a shock.”62

The additional information about not only the scope of the Iraqi program but also its actual progress led to revised estimates of when Iraq could have had its first atomic bomb, and when it would have been able to produce bombs in quantity. The Joint Atomic Energy Intelligence Committee estimate of 1990, which suggested that a crash program could have produced a bomb within a year, gave way to new judgments based on discovery of problems that the Iraqis had experienced with respect to enriching uranium and perfecting implosion. By mid-1992 it was estimated that it would have taken Jaffar and his colleagues another two to three years after the beginning of the Gulf War, or more, to have a working bomb.63

In the immediate aftermath of the war, there was still uncertainty within the U.S. intelligence community and the IAEA as to who actually headed the Iraqi program. Both U.S. and IAEA officials believed there was a yet-to-be-identified “mastermind.” The existence of such an unknown official, possibly a foreigner, followed from the belief of UN officials that none of the Iraqi scientists they had encountered, including Jaffar, knew about all aspects of the nuclear program, from enrichment efforts to weapons design. UNSCOM executive chairman Rolf Ekeus was “rather convinced that there must be someone who links the enrichment and design sides.” But by early October, David Kay’s IAEA team believed, based on its examination of the Petrochemical-3 employee lists, that Jaffar Dhia Jaffar not only was a “senior administrator” in the program who was “intimately linked to the uranium enrichment program,” but also “had the lead technical and administrative responsibility for the nuclear weapons program as a whole.”64

The belief that the key elements of the Iraqi program had been identified by late 1991 did not mean an end to further inquiries, as several defectors’ claims had to be followed up and there was every expectation that Iraq would seek to reconstitute its weapons of mass destruction capability. At least one defector had insisted that Iraq’s nuclear program involved one or more underground facilities, including a uranium enrichment plant in a mountain in the vicinity of Mosul. No such facility was discovered there. And no evidence turned up that Iraq had anywhere near eighty-eight pounds of weapons-grade enriched uranium. Nor did the efforts of the tenth IAEA inspection team, which searched for an underground plutonium production reactor at the Saad-13 State Establishment in Salah Al-Din province, bear fruit—a search possibly inspired by the 1986 Chinese reactor study. The team would ultimately report that “information and documents gathered during the inspection do not support the reports that such an underground facility exists at this site.” Earlier searches, by the ninth inspection team, of specific sites where intelligence, presumably from defectors, indicated such a reactor might be hidden also came up empty.65

By that time the CIA had also discounted other defector information indicating that Iraq had secretly enriched a sufficient quantity of uranium to produce one to three nuclear devices. As more data was gathered, intelligence analysts reached a consensus that Iraq had probably produced only a few grams of plutonium and only a few pounds of uranium.66

In mid-April 1992, following the destruction of Al Atheer, Iraqi trucks were photographed, probably by one or more KH-11 satellites, hauling equipment back into known manufacturing facilities, having apparently concluded they would not be receiving further visits from IAEA inspectors.67

Such intelligence was undoubtedly one factor in the assessment presented in 1993 to the House Foreign Affairs Committee by Robert Gallucci, back at the State Department as an assistant secretary of state. “Over the long term,” he told the representatives, “Iraq still presents a nuclear threat. We believed that Saddam Hussein is committed to rebuilding a nuclear weapon capability, using indigenous and imported resources,” a judgment that had been reached by the National Intelligence Council at least as early as June 1991.68

Between Gulf War aerial attacks and IAEA-supervised demolition, key Iraqi nuclear facilities lay in ruins. Tuwaitha, according to the IAEA, had been “devastated,” with much of its equipment destroyed during the war. Al Qaim, Al Jazirah, Tarmiya, and Al Atheer were also severely damaged. But Gallucci noted that Iraq had retained “its most critical resource for any nuclear weapons program”: skilled personnel and expertise. Iraq had also retained “a basic industrial capability to support a nuclear weapons program, including a large amount of dual-use equipment and facilities.” He also observed that if sanctions were to be lifted, Iraq would have access to additional financial resources for overseas procurement activities. Finally, Gallucci reported, “Iraq has still refused to provide the UN with details of its clandestine procurement network, a network which could therefore be reactivated in the future.”69

Gallucci’s statement, along with the written statements the IAEA submitted to the same committee before which the assistant secretary appeared, implied the need for continued monitoring of personnel, rebuilding efforts, and nuclear commerce. The IAEA noted that “Iraq could constitute a weapons program faster than another state that had never tried. The capable scientists remain. How they are currently employed is difficult to ascertain because they had been dispersed.” The agency also told the committee that it was “highly probable” that some documents about the nuclear weapons program “remain safely hidden away.” The physical facilities would of course “have to be rebuilt at great cost.”70

THE IAEA was correct. Just as Carl Friedrich von Weizsäcker had tried to hide some of his nuclear documents at the end of World War II, Mahdi Obeidi, following orders from Qusay Hussein in 1992 to keep the documents for the centrifuge project safe, hid his set in a fifty-gallon drum, which he then buried beneath a lotus tree in his rose garden. Inside were the detailed plans and design drawings required to manufacture centrifuges. Altogether there were more than two hundred booklets, instruction manuals for constructing each piece of the centrifuge and then assembling them.71

Along with the documents were the prototypes for four of the most advanced centrifuge components, which were small enough to fit in a suitcase. One of the parts was the ball bearing on which the centrifuge rotor sits. About the shape of a toy top, it balances the centrifuge rotor tube as it rotates at speeds in excess of sixty thousand revolutions a minute. Another was the centrifuge motor, about the size of a round loaf of bread, which contains magnets and coils that drive the centrifuge. By creating an extraordinarily powerful electromagnetic field, the magnets spin the centrifuge without actually touching it. There were also two segmented aluminum-nickel-cobalt magnetic discs connected by slight thread steel, which made up the magnetic upper bearing. From their place at the top of the centrifuge, the discs hold the rotor in place in a vacuum as it spins at supersonic speeds. Also stored in the drum was the bellows, a thin, gun metal–colored disc about six inches in diameter and two inches tall, which connected centrifuge tubes end-to-end—increasing the length of the centrifuge, resulting in a version that can enrich uranium substantially faster.72

CONCERN THAT IRAQ would seek to reconstitute its nuclear, chemical, biological, and ballistic missile programs, based on both its obsessive prewar quest and the continuing attempts to obstruct and deceive UN inspectors, guaranteed continued inspections by the UN and close monitoring by the United States and other nations. In an August 1993 letter William Studeman, the acting director of central intelligence, informed a Senate committee that “efforts undertaken by the IAEA to collect samples from Iraqi waterways offer us the greatest assurance that Iraq does not have a secret supply of bomb-usable material.”73

Other components of the Iraqi program—equipment, technology, and materials—still needed to be kept under scrutiny by the IAEA and United States. The international agency’s plan for a long-term monitoring effort, which led Iraq to establish the National Monitoring Directorate to interact with and obstruct the inspectors, would be complemented by the efforts of the U.S. and other national intelligence communities. The following year, the Arms Control and Disarmament Agency noted that “the United States believes Baghdad is continuing its effort to circumvent inspections and preserve as much nuclear-related technology as possible for a renewed weapons effort.”74

In April 1995 Hans Blix’s report to the Security Council provided some reassurance. He informed the council that “the essential components of Iraq’s past clandestine nuclear program have been identified and have been destroyed, removed, or rendered harmless . . . [and] the scope of the past program is well understood.” He also reported that “areas of residual uncertainty have been progressively reduced to a level of detail, the full knowledge of which is not likely to affect the overall picture.”75

But there was more to learn than just some details. In August 1995 the UN inspectors, the CIA, and other interested intelligence agencies would reap a significant intelligence bonanza when Lt. Gen. Hussein Kamel, a cousin and son-in-law of Saddam’s, would flee Iraq. Kamel, along with his brother Saddam Kamel, also a son-in-law of Saddam’s, arrived in Jordan on the night of August 7 in a convoy of black Mercedes automobiles that carried him out of Iraq and away from the immediate threat posed by increasing family infighting, which was constantly exacerbated by Saddam’s out-of-control son Uday.76

If the brothers knew nothing more than the details of that infighting, they would have been of interest to the CIA and other intelligence organizations. But they knew much more. Saddam Kamel was a lieutenant colonel in the Amn al-Khass presidential security service. Hussein Kamel had even more intelligence value, having served as undersecretary at the Ministry of Industrialization and Military Industry and subsequently as minister of defense. Of particular importance to the CIA and IAEA, he had been responsible for oversight of Iraq’s weapons of mass destruction programs, and knew the details of their current status and the attempts to conceal past activities and current capabilities.77

Six months after his defection Hussein Kamel would return to Iraq, having failed to establish himself as a future leader of Iraq while in exile. Not surprisingly, despite Saddam’s pledge of amnesty, he would die in a shootout engineered by Saddam, while Uday and Qusay watched. But in the months shortly after his defection he was debriefed by a variety of international and national organizations. On the evening of August 22 in Jordan, he met with UNSCOM chief Rolf Ekeus, the IAEA’s Maurizio Zifferero, and UNSCOM’s Nikita Smidovich, who were interested in what Kamel had to say about Iraq’s chemical and biological weapons programs. An interpreter from the court of the King of Jordan attended. The meeting began at ten minutes before eight and concluded approximately three hours later.78

Kamel began by noting that Iraq initially had one reactor and four different projects to produce fissile material. He also reported that “a few months ago they had a new project, designated ‘Sodash,’” that involved burying equipment, some of which had been recently recovered, while other parts were “made to disappear.” In response to Zifferero’s questioning, Kamel indicated the equipment was related to the electromagnetic separation project at Tarmiya.79

Zifferero and Kamel also discussed Mahdi Obeidi’s centrifuge project at Rashdiya, whose existence, and Obeidi’s role as director, Kamel disclosed. The defector also told his audience that the Iraqis at the site were manufacturing centrifuges using maraging steel as well as carbon fibers, and they preferred the carbon-fiber centrifuges. When asked why Iraq had been willing to acknowledge the centrifuge effort but had not disclosed the Rashdiya site, instead claiming that the work took place at Tuwaitha, Kamel responded that “it was the strategy to hide, not to reveal the sites” and “they said that to divert attention.”80

Later in the debriefing, Zifferero turned to a reference to a “final experiment” in one of the documents recovered by the IAEA teams. What Zifferero wanted to know was whether the final experiment was a test or combat use. Kamel did not specifically answer that question, but characterized all the work related to testing as “only studies” and stated that Iraq “had never reached a point close to testing.”81

A key focus of the studies, Kamel told Zifferero, was finding a way to employ less enriched uranium in an effective bomb. He also disputed the notion that the crash project would have relied on Soviet-supplied uranium, explaining that while the French uranium was sufficiently enriched for use in bombs, the Soviet-supplied material was only 80 percent enriched and without an operational centrifuge program there was no means to boost it to bomb grade.82

Earlier Zifferero had asked a key question: “Were [sic] there any continuation of, or present nuclear activities, for example, EMIS, centrifuge?” Kamel provided some reassurance for the immediate future but confirmed fears that Saddam Hussein had not abandoned his longtime quest for nuclear power status. “No,” he answered, “but blueprints are still there on microfiches.”83

Kamel’s defection spurred the Iraqi government into action. Knowing that his disclosures could be highly embarrassing and provide hard details about Iraq’s recent weapons of mass destruction programs as well as the continued denial and deception campaign, Saddam tried to undercut the impact. Five days before Kamel’s meeting in Jordan with Ekeus, Zifferero, and Smidovich, Iraq issued a new declaration acknowledging that it had filled warheads with biological agents (anthrax and botulinum) and that it had started a crash program to develop a nuclear weapon. New information on the chemical and ballistic missile programs was also provided. In addition, Saddam’s threat, made in mid-July, to toss out the UN inspectors was rescinded. Iraq would further admit that Obeidi was the leader of the centrifuge program (which led to a meeting with IAEA inspectors, who also received a tour of the Engineering Design Center at Rashdiya), and that Iraqis were conducting a survey of less populated areas in the desert to dig a vertical shaft and horizontal chamber for a test.84

Iraq also “identified” the culprit responsible for concealing the truth about Iraq’s weapons efforts: none other than Lt. Gen. Hussein Kamel. After the declaration, Iraq turned over 680,000 pages of new material, much of which it claimed had been hidden on Kamel’s chicken farm in Haidar, a suburb of Baghdad. The episode did not, of course, represent the beginning of a new Iraqi attitude toward the UN inspectors or an end to attempts at concealment. The following years would be filled with continued Iraqi obstruction and harassment of the inspectors, refusal to turn over documents or actively assist the inspectors, and complaints by the UN Security Council about Iraqi actions. Saddam’s announcement on October 31, 1998, that Iraq would cease all cooperation with UNSCOM led to a withdrawal of all the inspectors, IAEA and UNSCOM, from Iraq by mid-December. Operation Desert Fox, a four-day bombing campaign, began on December 16.85

When the inspectors departed Iraq, they had, according to IAEA chief Blix, compiled a “technically coherent picture of Iraq’s clandestine nuclear programme. These verification activities have revealed no indication that Iraq possesses nuclear weapons or any meaningful amount of weapons-usable nuclear material, or that Iraq has retained any practical capability (facilities or hardware) for the production of such material.” But, the IAEA noted, a statement “that it has found ‘no indication’ of prohibited equipment, materials, or activities in Iraq is not the same as a statement of their ‘non-existence.’”86

The departure of the inspectors would have a significant impact on the ability of the CIA and other interested U.S. intelligence agencies to monitor any Iraqi attempts to rebuild its weapons of mass destruction programs. One constellation of NRO satellites could still send back detailed images of suspect facilities, while another could intercept Iraqi communications. Both the NSA and CIA also had capabilities for monitoring Iraqi communications at home and abroad, possibly detecting attempts to purchase materials related to nuclear or other weapons programs. In addition, the CIA could still attempt to recruit Iraqi assets and debrief defectors. But there would no longer be inspectors on the ground who could enter a suspect facility to determine if the deductions of imagery interpreters about what was going on inside were correct, or confirm the inferences drawn from a suspicious telephone conversation, or investigate the claims of a defector. Iraq was again a denied territory.

___________

* The report of the ninth IAEA inspection team explains the Iraqi cover story for the site—that it was first built in the 1980s by the Ministry of Agriculture for research and development in water irrigation technology but was turned over to the Ministry of Industry and Minerals in 1988, which established an Engineering Design Center in the northern part of the site while attempting to establish a paper mill/vocational training center under the forestry ministry in the southern part. After exploring the complex, the team reported that “there was no physical evidence or other signs of recent modifications which might suggest that this facility served some other purpose than what was declared.” The report did note that the director of the center “was unable to produce a single piece of paper related to its projects,” claiming that all records and reports were maintained at the locations where the staff was working or at the ministry. See S/23505, Note by the Secretary General, January 30, 1992 w/enclosure: Report on the Ninth IAEA On-Site Inspection in Iraq Under Security Council Resolution 687 (1991), 11–14 January 1992, pp. 14–15.

In late 1992, after repeated questioning, the Iraqis admitted that Rashdiya was home to one of the country’s senior centrifuge experts but claimed his presence simply resulted from his desire to work at that location. They continued to claim that the principal centrifuge sites were at Tuwaitha and Al Furat. In the absence of solid evidence inspectors disagreed as to the nature of Rashdiya’s activities throughout 1993 and 1994. See David Albright, “Masters of Deception,” Bulletin of the Atomic Scientists, May/June 1998, pp. 45–50 at p. 48.