(40)

BY THE END of the bobby-soxer days, the American masculine ideal was changing. Maybe that statement is always true. In Hollywood films, it used to be that the hero didn’t fail if he was played by Gary Cooper, John Wayne, Errol Flynn, or Clark Gable. Even in the 1940s there were exceptions, mainly from the noir tradition. Fred MacMurray plays the sap for Barbara Stanwyck in Double Indemnity; Robert Mitchum falls head over heels for Jane Greer in Out of the Past. There was the tragic gangster hero as played by James Cagney or Humphrey Bogart. And some manly specimens had glaring weaknesses and were no less attractive for it. In Hitchcock’s Spellbound, Gregory Peck suffers from amnesia and needs the Freudian and romantic therapy that psychoanalyst Ingrid Bergman is uniquely able to give him. Dana Andrews in The Best Years of Our Lives (1946) was a hero in a fighter plane but can’t hold a job as a soda jerk when he returns to his home town. The ultimate disaster befalls William Holden in Sunset Boulevard (1950). He is a kept man, a paid consort. And though his disembodied voice guides us in the voiceover, the rest of him lies face down in a swimming pool, dead in the water.

By the early 1950s, an inchoate new ideal was beginning to take shape: the cult of the outsider, the rebel. “We thought everybody in pain was holy,” writes Barbara Grizzuti Harrison, a self-described bohemian looking for “the secular equivalent of the Holy Grail” in jazz bars like the Five Spot in New York City. The “we” in that sentence is meant to stand for all the rebels who lacked causes, particularly the females of the species. The adjectives she was looking for in the men she met were “sensitive” and “vulnerable” and “risk-taking.” “We could accept any damned nonsense from a man provided it was haloed by poetic feeling.” The four men Harrison singles out as “heroes” of this radical new antiestablishment aesthetic are Sinatra, Brando, J. D. Salinger, and Albert Camus.

Why Sinatra? Because “he bucked the crowd, as heroes are meant to do. He was the Outsider who fought back and made it.” And because he transformed himself not only as a Capitol recording artist but as a film star.

In his first movies, Sinatra was the sidekick, the wingman, the naïf compared with worldly-wise Gene Kelly. In On the Town, the best of the early musicals, Frank plays Chip, the hick from the sticks with his antiquated guidebook. In keeping with the crooner’s carefully cultivated image, Chip is scared stiff of cab-driving Betty Garrett. She does her best to persuade him to “Come Up to My Place,” and he utters a frightened “no” as the taxi bobs and weaves amid the traffic and the potholes.

That image changed irrevocably with From Here to Eternity (1953) and Young at Heart (1954). The latter is particularly compelling as a portrait of the hero without a halo or a coat of armor (plus, you get to hear Sinatra and Doris Day sing). Young at Heart is a musical reworking of the 1938 movie Four Daughters, in which a handsome composer and his piano-playing arranger-slash-accompanist disrupt the lives of a happy small-town family headed by widower Claude Rains. In the original, John Garfield plays the composer’s sidekick, a loser, at war with destiny; Pauline Kael thought it was Garfield’s finest performance. In Young at Heart, Sinatra takes the Garfield role, except that he doesn’t die in the end. Into a fake suburban paradise Frankie enters and shakes things up. The ebullient, ever optimistic Laurie (Doris Day) is supposed to connect with handsome but hollow Gig Young, the man in the gray flannel suit. She falls instead for Sinatra’s character, Barney Sloan, the working-class loser with the lousy attitude. Barney is a would-be composer, and a strictly small-time lounge singer, who gets to sing Gersh-win (“Someone to Watch Over Me”), Porter (“Just One of Those Things”), and Arlen (“One for My Baby”) and tinges each with a noir inflection. Pauline Kael wasn’t crazy about it: “In the 30s when Garfield, a rootless product of the big city and the Depression, encounters the cozy life of a small-town middle-class family it enrages him by making him feel how deprived he had been; in the 50s when Sinatra, an orphan who had never found a place for himself, expresses the same kind of chip-on-the-shoulder bitterness he seems just a sorehead and loser.” Bill Zinsser, reviewing the movie for the New York Herald Tribune, saw things differently: “That morose face, that crooked smile, that sloppy posture, those hollow eyes—all are a pleasure to behold.” The film comes as close to nihilism as can be made consistent with a happy ending: Barney survives his suicide attempt and is welcomed by Laurie’s family.

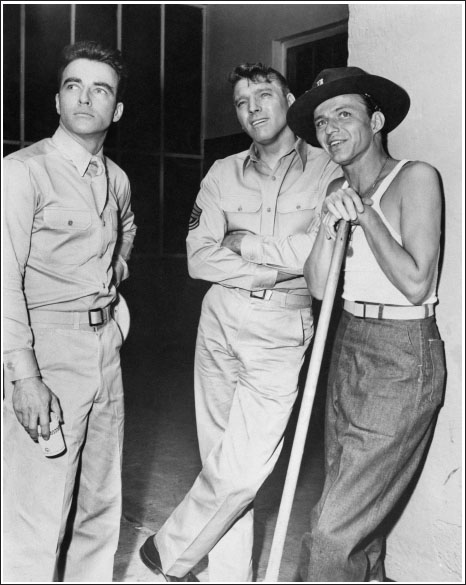

From Here to Eternity.

Mondadori / Getty Images

The antihero aesthetic goes even deeper in Sinatra’s next big dramatic role, that of Frankie Machine, who plays drums, deals cards, and shoots up in The Man with the Golden Arm (1955). Kael: “Frank Sinatra’s performance is pure gold . . . rhythmic, tense, and instinctive, yet beautifully controlled.” Sinatra was a little bummed out when Ernest Borgnine, in Marty, beat him out for the Oscar, but no way was Hollywood in 1955 going to favor a smack addict over a Bronx butcher who lives at home with his Italian mama and meets a nice girl, a high school teacher, at a dance.