WITH THE WALL of death bike built and the record broken, I could spend more time training for the Tour Divide. I didn’t know what I was letting myself in for. I knew it was 2,745 miles, alone and unsupported, only relying on what I could carry on my bike or my back. I knew it involved the equivalent of cycling up seven Mount Everests. I knew that the people who set quick times were sleeping rough for four hours or less a day, but the only way you know if you can finish something like the Tour Divide is to try to do it. I wanted to get a feel for what it might be like, so I planned a training ride with Jason Miles, the top endurance mountain-bike racer that I broke the 24-hour tandem distance record with in 2014. We called it ‘the coast to coast to coast’.

The idea was to ride from one coast of England to the far side of Scotland, get the ferry to Northern Ireland, then ride from the bottom to the top. We would treat it like I’d treat the Tour Divide: ride a bloody long way, sleep for a bit, ride some more. Not only did we want to leave the east coast and ride west, we also wanted to ride as many trail centres as we could do, and do the same in Ireland. Trail centres are purpose-built mountain-bike tracks that are dotted around the countryside. Some have nothing but a car park at the start and one or more signposted and maintained tracks through the woods to follow, others have cafés and bike shops and even elevated trail sections made from wood.

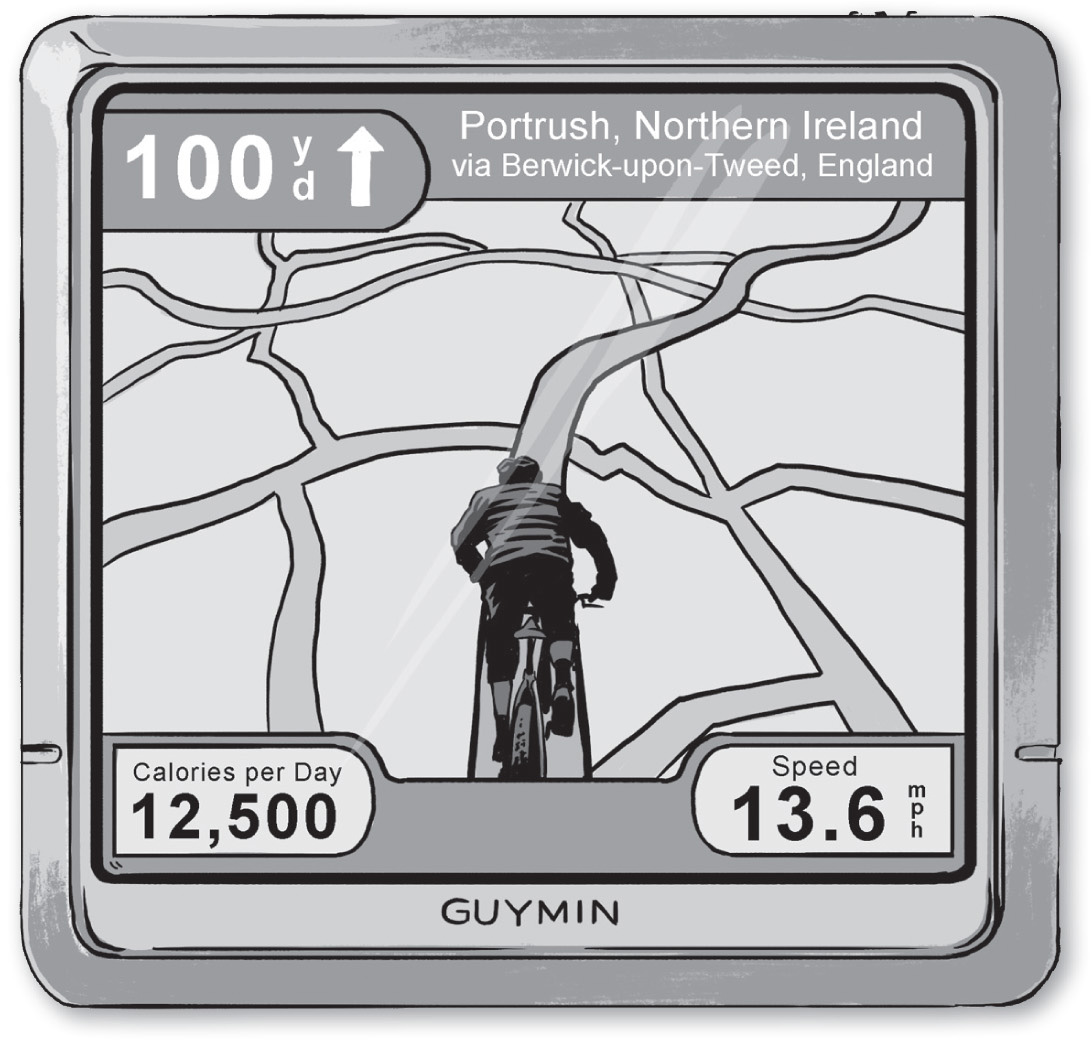

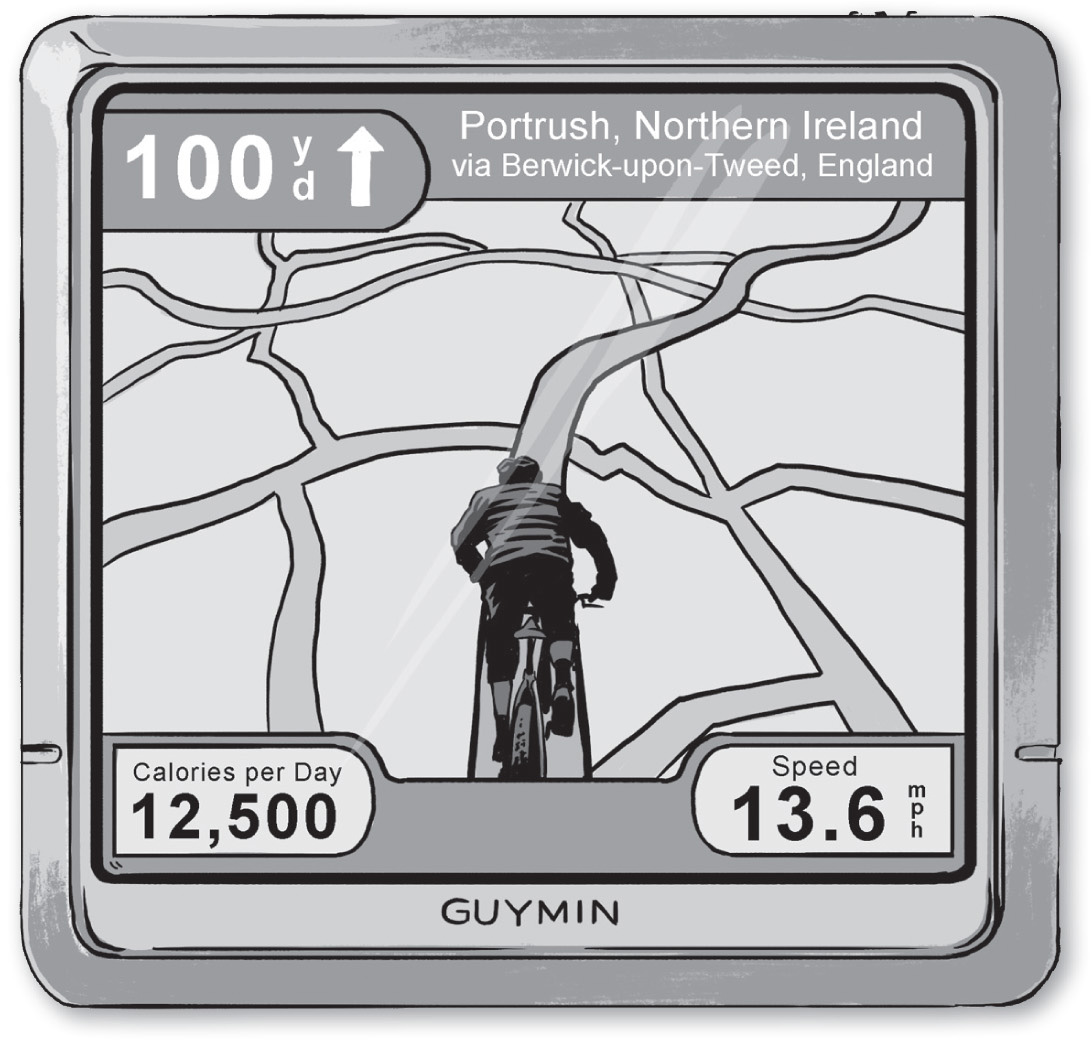

I chose Berwick-upon-Tweed, right on the Scottish border, as our start point. We would meet there late on the night of Wednesday 13 April. With the Tour Divide filling my head I came up with another idea. Any spare time I had I wanted to spend riding, so any way I could lengthen the ride I thought was a good idea. I worked late on Tuesday night, getting everything finished at the truck yard, and instead of driving up to Berwick, I reckoned I’d ride there to meet Jason.

So, at eight on Wednesday morning, I left home on the Salsa Fargo I planned to ride in the Tour Divide. This wasn’t the first long ride I’d done in 2016. In January I set off from home, rode to the north of Scotland and, once I got there, had a night in a hotel before taking part in the Strathpuffer 24-hour mountain-bike race, which I’d done a few times before. It was cold and hard, dark and wet for most of the time, but what did I expect? It was January, in Scotland.

I rode on my Rourke single speed, so only one gear, meaning I had to slog up the hills in a gear higher than you might normally use. I’d ridden up through England on my own, but then 50 miles south of Edinburgh I met Alan, who, along with the Dungait brothers, I’d done a lot of biking with for years. We rode together from there up to Strathpuffer, a village in the Highlands, north of Inverness, where the event is held. On the way up the chain had totally dried out and was graunching like hell because of all the shit and blather. Alan had an idea to get some butter from a café to lubricate it.

The ride to the Strathpuffer was another thing I’d set my mind to do and it hadn’t broken me, even though it was only a few months after the operation to bolt my spine together. The weather wouldn’t be as bad on the coast to coast to coast, but the mileage would be higher.

Leaving Grimsby, I didn’t use a map. I was just riding off the compass on the Garmin, heading north. As long as I kept going that way I’d work it out. I rode over the Humber Bridge into Yorkshire, staying on small roads from then on. From Malton I knew a few back roads, and I knew that when I got to Northallerton I wanted to be heading more north-east, and then a bit north-west.

Last time I rode up this way, to the Strathpuffer, I went a bit further west, so this time I stuck east and headed towards the North York Moors. I got to the topside of Malton and followed true north on goat tracks. Five miles in, I was wondering if I’d done the right thing. It was a proper dirt track, which was alright, because I was on a mountain bike – a bit of an oddball-looking mountain bike, but built to cope with it. The bike was loaded up with sleeping bag, roll mats, inner tubes, chain, spare set of clothes and toothbrush. I didn’t know where the trail would end, but I knew it wouldn’t be a dead end. You never reach a dead end on a mountain bike because one dirt track always leads to another. The weather was spot on till one or two in the afternoon, then it pissed it down for most of the day and night. After 50 miles of these tracks, seeing no one, I came to a road with no idea where I was. I cycled into the nearest village and found out it was Great Ayton, near Guisborough. I was in Yorkshire, but only just, and right on the Cleveland border, eight miles from the centre of Middlesbrough.

It was four or five o’clock, and I found somewhere in the village to get loaded up with pork pies. I was loving the ride, even though I was soaked through. I had no one telling me what to do, no phone, and all I had to do was follow my compass and pedal north. It was great. It doesn’t have to stop raining for long for you to dry out. I was wearing Lycra leggings with baggy shorts over the top; a Hope cagoule-type thing and Endura wool top; short socks; Endura gloves; and Sidi cycling shoes with old waterproof overshoes that I taped to my feet and only took off once in four days.

As I rode around Middlesbrough, the weather was misling – that drizzly, misty, soaking rain. I had the choice of bridle paths from Middlesbrough nearly to Newcastle, but they’d take me a fair way west before I got going north again. I’d been on them before and the Garmin will take me on them, but the A19 is true north. It’s legal to ride a bike on this dual carriageway, but you’re an idiot if you do. It’s so dangerous – you’re asking to get run over. But, I thought to myself, it’s rush hour, the roads are heaving, so nothing is going too fast. Confirming that I am an idiot I set off towards Newcastle on the A19, and pedalled the 35 miles right to the Tyne Tunnel.

You’re not allowed to ride a pushbike through the Tyne Tunnel. You have to go into the office and they put the bike in a van and take you through. I’d met the maintenance lads in the office when I’d cycled up to the Strathpuffer in January, and they remembered me from then. I had a brew in their tea room.

I’d gone from Yorkshire with the ‘Tha knows’ accent, not seen anyone, then come out in Great Ayton, with a Middlesbrough accent, and now I was at the Tyne Tunnel with ‘Hadoway and shite, champion man’ Geordies. I’d only been on my bike half a day and I’d heard all these different accents.

It was seven or eight by the time I got through the Tyne Tunnel, and I knew Berwick was 70 or 80 miles north on B roads, so I decided to ride up the more direct way on the A1 rather than going on the coast road. Again, I was asking for trouble, pushbiking on such a fast and busy road, but I got away with it. And north of Newcastle the A1 isn’t like it is south of the city. It’s a two-way road for a lot of the way.

I reached Berwick after two on Thursday morning, 18 hours after leaving home.

I’m not a big McDonald’s fan, but I’ll stop in for tea if there’s nowhere else, and I would spend a lot of time in McDonald’s on this ride. Those 24-hour places are good when you’re pushbiking like this. They’re open, for a start, they’ve got bogs with hand driers, they’re handy for loading up calories, and as long as you keep eating it doesn’t matter what you look or smell like, they let you in. I chose the fattest thing I could see. I get the biggest burger with the most shit on it possible. What I realised on these rides was that every McDonald’s plays the same music. It made me wonder, in a small way, what our world is coming to. It doesn’t matter if you’re in Northern Ireland or London, the music is the same. I imagined them having meetings at head office about what kind of music is going to be on next month’s playlist. The answer is always the same: ‘Just modern shit.’ I kipped in the McDonald’s for half an hour, with my forehead on the table, waiting for Jason.

When he arrived, having left home at one in the morning to drive up from Manchester, he unloaded his bike, parked his car where he was happy to leave it for three or four days, and we went over the plan quickly before setting off at five. The first part of the route was six hours on the road from Berwick to the first trail centre at Innerleithen. We met another lad, Sam, one of Jason’s mates, who would do the rest of the Scottish part of the route with us.

Innerleithen, near Peebles, on the Scottish border, is one of the 7stanes mountain-bike trail centres on Scottish Forestry Commission land. There are eight locations, but Innerleithen and nearby Glentress are counted as one, and the trail centres are spread across the width of Scotland, all south of Glasgow and Edinburgh. The stane part of the name comes from the old Scottish word for stone, and there is a carved stone at each of the centres. There are trail centres all over Britain, but the 7stanes are some of the most popular – a big draw for folk from the whole of Scotland and beyond.

We weren’t going hard at it, pacing ourselves for the rest of the ride, but we were going too hard to talk. The 11-mile loop around Innerleithen took summat like two hours. There wasn’t a café or anything there, so we set off straight away to Glentress, only half an hour’s ride down the road, for a good feed there. This is one of those trail centres with good facilities, like a bike shop, café, a bike-hire place and even showers. We only needed the café, and I had a jacket potato with everything you can get on it and a massive slice of cake. Anything with calories will do. I had been nibbling on pork scratchings all the time too. On a ride like this I get sick of eating. You’re burning so many calories, and if you begin to feel hungry, it’s too late. You can’t let your body run into the reserve, because your energy has gone. Every bakery or butcher’s I passed I would stop. I had an hour’s kip at Glentress at the side of the road. I was out like a light. I hadn’t slept since Tuesday night, and it was Thursday dinnertime. I wasn’t hanging out my arse, but we knew we weren’t going to make Newcastleton, the next trail centre, in the daylight, so it didn’t matter if I had an hour’s sleep.

I hadn’t washed since Tuesday, and I was suffering with rashes from the stale sweat and dry skin – even up my nose was giving me grief. We left Glentress at four, heading for Newcastleton, 60 miles away to the south-east, in the middle of nowhere and in the opposite direction to the west coast we were aiming for.

We reached Newcastleton on B roads, arriving there at gone midnight. I put any extra clothes I had over what I was already wearing and swapped my cycling helmet for a woolly hat, before climbing into my sleeping bag at the side of the road. I didn’t have a tent – I wouldn’t take one on the Tour Divide, so there was no point. I had two or three hours’ kip, but I was still cold. It felt like good practice for America.

We got up at first light, about five o’clock, and rode the Newcastleton trail for a couple of hours. People drive for hours to get to the trail centres for a pedal round, and I was enjoying riding them, even though the bike I was on wasn’t the best tool for the job. It’s got a hardtail, only 100 mm of front suspension travel and those handlebars, but it was going to have to do the same kind of riding that the trail centres would throw at it in America, so I wanted to give it stick to see what, if anything, broke on it or needed changing. Something like an Orange Gyro or Five, a full-suspension bike, would be better for the trail centres, a bike that deals with the ruts and bumps at speed. But they’re heavier bikes, and that weight, multiplied over 2,745 miles and all that climbing, is no good. The Salsa I was riding had drop bars, called woodcutter bars, not regular mountain-bike bars, and it wasn’t easy riding trails with them, but I had to try it. The benefit of the bars, with extra time-trialling bars bolted to them, is that they give a load of variation to where you can put your hands so you can change your body position and give yourself a rest. It’s comfy, but the bike’s slow because it’s still a heavy bike compared to the one I’d use to race in the Strathpuffer.

We headed to the village shop to get breakfast. My method for deciding what to eat was picking up what looked tasty and comparing the weight of everything in my hand to see which was the heaviest. I picked up some custard slices, and they were heavy buggers, so I had them, thinking they’d be full of calories.

The next trail centre was Ae Forest, just west of the M74 near Dumfries. I had probably covered 350 or 400 miles since leaving home, and we had 40-odd miles and three hours to Ae. We stopped at a café for a banana milkshake, feeling under no pressure. I rang up Nutt Travel in Northern Ireland, to book a ferry.

At Ae we met Michael Bonney from Orange, the mountain-bike company. He was one of the top men there and I met him after I mentioned I had an Orange in a column for Performance Bikes years ago. Back in March 2013, Michael was out on a road ride with friends when he crashed his bicycle, just from a second’s loss of concentration, and went off the side of the road. It wasn’t anything unusual, the kind of crash people have all the time and climb back on their bike with nothing worse than a skinned knee, but Michael broke his neck and severed his spinal cord and was permanently paralysed from the neck down. A charitable trust was set up for him, and someone suggested our coast-to-coast-to-coast ride could become a way of raising money. I had no problem with that. I was doing the ride anyway, and we did it in aid of the Ride for Michael Trust.

There was a local TV crew at Ae Forest. I’m not sure how they happened to be there, but it must have been someone at the Trust who organised it. I’m not a big charity sort of man, but I have done plenty of stuff when it’s meant something to me, and if it could help Michael out, then all well and good. He’s had it hard and he’s getting on with it, and I admire that. People had kindly donated money, and Michael got summat like £5,000 from the coast to coast to coast, I was told.

We didn’t have time to ride the Ae Forest trail because we had to get to Cairnryan for the ferry. We missed the Kirroughtree trail centre too, because we were running a bit late and it was pissing it down. It was 85 miles to Cairnryan, and we had eight hours to do it. Now we were taking turns at the front, like they do in races like the Tour de France. The rider at the front is taking the brunt of the wind and those behind are riding close enough to be in the slipstream and have a slightly easier time of it. You do your bit at the front – don’t go mad, only a few minutes – then pull out to the right so the other riders can come up the inside of you, and then you tag on the end, the place that’s got the most aerodynamic benefit. You recover as best you can for another shift at the front. My arse was a bit sore by this point. I was trying a new seat. I’d always used SDG seats, but the Salsa came with a WTB and I quite liked it.

People go out for an 85-mile ride on a weekend and it would be a proper ride, but we had 85 miles to go in the dark to the ferry, and I’d already done 205 miles the first day and over 400 miles since leaving home. It was minus two with the wind chill and pissing it down. I wasn’t cold while I was on the bike, but as soon as you stop it gets you.

Sam wasn’t going to Ireland with us, so his dad met us at the ferry. We climbed in the back of his van and had a brew. Jason was shivering so much he was spilling his tea. He’s as hard as nails, but he thought he was borderline hypothermic. He said, ‘We have to get going.’ He wasn’t saying he wanted to stay in the van longer to get warm. He knew that getting back on the bike and starting pedalling again would be better.

We rolled on to the P&O ferry from Cairnryan to Larne. Cairnryan is near Stranraer, and if you’ve ever had to ride or drive there for the ferry to Ireland or the Isle of Man, you know it’s a long way west.

We got another right feed on the ferry and the crew really looked after us. We were let into the lounge, and because we were soaking, one of the crew asked if we’d like our shoes putting in the drying room. There was complimentary wine, so me and Jason drank a bottle between us. Red wine has a good calorie value, so it was doing us good.

It was only a two-hour crossing, so there was next to no time to sleep, but I dropped off. The next thing: ‘Bing-bong. Can drivers please return to their vehicles.’ Fuck! We rolled off the ferry at two in the morning and a group of Irish lads I’d been talking to were there to meet us. Fair play to them, they were keen.

The Irish group were Geoff, Dave and Mike. They’d been training like hell since before August, and I got the feeling this was going to be like their Olympics. I only really knew Geoff before this. He worked for Chain Reaction Cycles, the massive mail-order company in Northern Ireland. He was the youngest of this group, in his mid-thirties, and he was one of the people behind the Ride for Michael Trust. Dave was late-forties and fit. He did 14,000 miles of cycling in 2015, so he’s not a messer. Mike was between the other two in age, worked for Orange mountain bikes and came over from England for the ride. They were all riding mountain bikes, because that was the rule I’d made. Originally, my mate Tim was going to follow us in a van and we’d have road bikes for the road sections, then swap for mountain bikes for the trail centres, but I decided, a couple of weeks before, that it wasn’t what I needed to do to prepare for the Tour Divide. I needed to test myself by having no support – just one bike and whatever I could carry.

Before we really got going, we biked to Geoff’s house for Weetabix and tea, then we were back on the bikes at 5 am, heading south to a trail centre in the middle of Belfast, the Barnett trails.

We were aiming for some of the main trail centres in Northern Ireland. The next was Castlewellan, 40 miles south of Belfast, where we ate again and rode the trail. Next we headed over to Rostrevor, on the banks of Carlingford Lough, in Newry, right on the border. That was near-on 30 miles away, so after riding the trail it was time for another feed in the caff, then Jase and I had half an hour’s kip on the grass bank outside. The sun was in the right place and I might have even got a bit sunburnt. I was absolutely knackered, but it was great. It felt like no one gave a damn about what we were doing. We were just five blokes out riding and I was loving it.

I didn’t even know what day it was. I thought it was Friday, but it was Saturday. By the time we left Rostrevor it was five or six in the evening. We had more food outside Newry, probably four hours after the last feed. The chef came out, told us about the soup of the day and it sounded good, so I had that, thinking that I should give me guts something a bit easier to digest.

From the diner we headed to Davagh Forest trails, to the north-west of Cookstown, where the first motorcycle road race of the year is traditionally held, and a place that sometimes reminds me, after a long winter, of why I love road racing. This year was different. I wasn’t racing until at least after the Tour Divide in June. The ride from Rostrevor to Davagh took us past Armagh, Portadown, Dungannon and Cookstown. It was all of 70 miles, and into a headwind, something we didn’t need by this point.

We met a couple of lads I’ve known for years, Richard and Darren, who were supposed to ride with us, but we were later than we intended and it knackered up their plans. Instead, they sat in their van waiting for us for hours, then made us a much-needed cup of tea, but didn’t bother riding. We got to Davagh Forest at some stupid time in the middle of the night. The ground was frozen, so we decided not to ride the trail. The Irish lads were suffering, but we kept at it, on to Desertmartin, Swatragh, Garvagh, Coleraine, Portrush. The last two towns being main points on the North West 200 course.

Just north of Swatragh I crashed, falling asleep while I was riding. My legs felt good and were still putting power out, but my brain needed a rest. I’d only slept four and a half hours, or not much more, since I’d left home four days ago. I didn’t hurt myself. I had kept slapping myself around the face, trying to keep myself awake, but it didn’t work.

I explained to Jason that I wasn’t weak-kneed, but I needed five minutes, so I slept in a bus shelter. I bet I was only sat on the floor for five seconds before I was asleep. I’d said I needed five minutes, and five minutes later Jason woke me up and said, ‘Alright, let’s get going.’ I could’ve slept for eight hours, I bet, but that five minutes was enough to keep me going for another few hours. It was four or five in the morning, and not long after that forty winks the sun started coming up, which tricks the brain into thinking it’s had more sleep that it has. Along the way we found a McDonald’s. It was playing the same music, and that really annoyed me, but not enough to stop me from going in and filling my face.

We biked to Geoff’s mum and dad’s place in Portrush, right on the north coast of Northern Ireland. We were finished and still smiling. His parents weren’t there, but his wife, Margaret, was and she cooked us steak and chips. From there, David took me and Jason to the ferry terminal in Larne in his car. I’d done over 750 miles by that point, so I wasn’t wimping out by not riding to Larne. We had two hours on the ferry and it was chocka. A family in the corner had a right comfy bit and said we could sit with them, so we did and fell asleep. Sharon was waiting for us in the van at the ferry port when we docked at four in the afternoon. I climbed straight in the back of the van with the bikes and slept for four hours while she drove the 180 miles across the country to Berwick-upon-Tweed, where we dropped Jason off at his car. It was straight down the A1 for me and Sharon, and we got home at midnight. I went to work the next morning, in for eight. I didn’t bike in. I was going to but Jason told me to have a few days’ recovery, then have a big week the following week. I’d do a 50-hour week before the Tour Divide, then that would be it for serious training.

The longest I’d sat on a bike before this was the ride up to Inverness, which was a fair way, just over 500 miles, with over 100 miles of riding on the Strathpuffer itself. The coast to coast to coast was over 750 miles, from Wednesday morning to Sunday morning, and I’d learned a lot. The Rohloff hub I’d chosen wasn’t the most precise thing, but it was reliable. My wheels needed to be lighter, because it took too long to accelerate. The bike was comfortable enough, but I needed to put more cream on my arse for saddle-sore. I needed more painkillers – nothing fancy, just ibuprofen, or vitamin I as some cyclists call it. When we were on the road, my arse and knees were getting sore and Jason was aching too, his back and arse, so he got on the painkillers and I asked, ‘What are you doing with them?’ He told me it just takes the edge off. I knew I had to take regular multivitamins to America, because you’re eating so much fatty, greasy rubbish that you need vitamins to keep you right.

I learned that I know my pace. I know that when hills get steep I should get off and push for a bit, not kill myself every five minutes to make a climb, because if I do that I won’t last. So I was pushing up hills in Ireland that I could ride up on a normal day’s ride. You need a different mindset when you know you’re cycling for 750 miles, or 2,745 miles. You’ve got to know that if you’re only doing 3 or 4 mph and your heart rate is up to 180 or 190 bpm while you’re crawling up the hill, you’re not gaining anything. You can walk at that speed and get your heart rate down. And you have the added benefit that it stretches your legs. I only walked for five minutes or something at a time, until the gradient slackened off, then got back on. Jason would slog on, but that’s him and he was on his featherweight race bike, not that I’m making excuses.

I also found that I couldn’t eat enough. I did 55 hours of biking, at least 750 miles and 10,500 metres of climbing, and burnt something like 50,000 calories in just over four days. On the Tour Divide you’ve got to deal with self-cannibalisation, when the body has used up all the glycogen, the body’s natural stored energy source, because you can’t get enough food, and starts to eat at the muscles for energy. Tour de France riders can lose a lot of weight, but they’re not riding long enough per day for self-cannibalisation to be a problem. The Tour de France is seen as the hardest race in the world, but the Tour Divide is more miles in less time, with no support and the riders sleeping rough, so you tell me what’s the toughest race. Yes, the pace is slower, but Tour Divide riders are on the bike for more hours every day and it’s a mountain bike, off-road.

This coast to coast to coast filled me with confidence, and I reckoned I could’ve done that pace for two weeks, which is what I’d have to do on the Tour Divide. It was scary thinking about it, but I was fascinated about what would be going through my mind at the end of it. Before then, though, I had a job on with a rebuilt Transit Custom.