THE TV BODS at North One were looking for ideas for stuff I could do for another series of Speed. A mate had told me about a couple of races in Nevada, flat-out, 90-mile time trials, held on closed public roads. The races are called the Silver State Classic Challenge and the Nevada Open Road Challenge. North One liked the sound of them.

When the TV lot started talking about a race in America, the idea turned to me doing the Nevada Open Road Challenge in a Transit van. Then everyone agreed it would be a lot better if it was done in a van that had some link to me, instead of one we might be able to get from Ford. They asked, ‘Have you got a Transit van?’ Well, actually, I have …

Between me, Andy Spellman and North One, we came up with the plan to turn the black Custom I’d written off and bought back from the insurance company into Supervan 4, and I’d go and race it out in Nevada. After everything that had gone wrong with the van, it sounded like it couldn’t have worked out better.

Ford had been building promotional vans out of Transits since 1971, calling them Supervans. The first was a Mark 1 Transit fitted with a V8 engine from the famous Ford GT40 sports car.

Built in 1984, Supervan 2 had a version of a Cosworth DFV V8 F1 engine, rear-mounted on a Ford C100 Group C racing-car chassis with the fibreglass body of a Mark 2 Transit over the top. Really, it was a Le Mans racing-car chassis with an F1 engine in it and a fibreglass shell. It would do 174 mph, but it wasn’t really usable. The engine was so highly strung that it needed pre-heating before you could start it, and a team of mechanics to look after it whenever it ran anywhere. And Ford had used a body shape that was just about to be replaced with a new production van, so, from a marketing point of view, it was out of date not long after being built. It was only used for a year before it was retired.

Supervan 3 appeared in 1994 and was used to promote the new Mark 5. It had a seven-eighths scale fibreglass body and was originally fitted with a Cosworth HB V8 F1 engine, the same type that powered Michael Schumacher’s Benetton when he won his first F1 title in 1994. The Supervan’s engine was eventually replaced with a Ford Cosworth 3-litre V6, so it could be more usable. Mine could be thought of as Supervan 4, making it legendary in the Transit world.

North One decided they’d use Krazy Horse to manage the building of the van. The company’s boss, Paul Beamish, is really into his hot rods and American muscle cars. The shop is also a Morgan dealer, so they had the facilities and mechanics to do it. The TV lot trusted Krazy Horse because they’d proved how hard they worked on the wall of death, and they were on the same wavelength.

The van would be completely modified: V6 twin-turbo engine; converted from front- to rear-wheel drive; roll cage; massive brakes; coil-over suspension.

There are different classes to enter in the Nevada Challenge race. You tell the organisers which class you want to run in – 100 mph, 140, 150 or unlimited – and I was going to be in the 150 mph class. The idea is to cover the 90-mile course at as close to an average of 150 mph as possible, but it’s harder than it sounds. I was told that in the 2015 race, a boy who was summat like two-tenths of a second off the perfect time for averaging 150 mph over the 90-mile course wasn’t even in the top 20.

I had no idea how I was going to drive 90 miles that accurately. I would have a local co-driver, or navigator, as they call them in this race, a man who knows where to go steady and where to give it the berries. And the race was in May, so not even two months after the wall of death attempt I would be going to America to race what might be the world’s fastest van. I just hoped there wouldn’t be any parked car transporters in the way.

At the beginning of December 2015, my wrecked Transit Custom, FT13 AFK, was collected and taken to Krazy Horse in Bury St Edmunds, Suffolk. I followed it for the first day of filming on the Speed programme. Paul Beamish, his salesman Stuart, who has built hot rods all his life, and Krazy Horse’s mechanic Dan Sims were there, and some wild ideas were chucked about. Ford V8s and rear-mounted turbos were all discussed before a plan was decided while the cameras filmed it all.

The next day the van was taken to Baker Body Craft in Mildenhall, a specialist body-repair company that Krazy Horse trust. They set about straightening the van and ended up putting an A-pillar in it. An A-pillar is the upright that runs from the sill, has the door hinges fasten to it then forms the side windscreen frame and carries on to join the roof panel. You know a car or van is near enough buggered if it needs an A-pillar in it.

I went back to the wall of death job that was looming, while Dan got on with the Transit. He would be the foreman in charge of modifying my van. I would have loved to do it, but it was being built at the same time that I was flat out with the wall of death bike, so I didn’t lay a hand on it. Dan was the brains behind the whole job. He’s 32 and a real good lad. He had worked as a Mercedes mechanic for 13 years, starting out as an apprentice and working up to diagnostic technician on all vehicles, from smart cars up to Sprinter vans and everything in between, including AMG Mercs. He’d been at Krazy Horse just short of a year when he started on the Transit.

He set about putting meat on the bones of the plan while Craig McAlpine, one of the subby researchers at North One, contacted Ford GB to tell them what we were doing. Craig’s in his mid-twenties and dead into his cars, so he was the ideal man for this job. Ford offered North One a special Tourneo, the minibus version of the Transit, that their motorsport department had fitted with a 400-horsepower V6 EcoBoost engine, a six-speed manual gearbox and a Ford F-150 pick-up back axle. Tourneos are only ever front-wheel drive, like Transit Customs, but Ford’s motorsport lads had wanged this eff-off engine, Mustang gearbox and a back axle in it for the fun of it. It had been chucked together by some of the mechanics – a few of them had been involved in the Supervan projects – but it was never supposed to see the light of day. It was only ever a tea-break and after-work project – an experiment – that was never meant to be anything fancy. We were told that the Tourneo project had been shelved, but they were happy to help us.

Ford were never going to do anything with this special van, except crush it, so they told the TV lot that we could take whatever we needed off it. Dan took the ideas from the Tourneo, but not a lot more, then did it his own way.

On 28 January, Dan took the Tourneo to Millbrook Proving Ground, the specialist automotive industry test facility, near Bedford, to see what it could do. He got 138.5 mph on the bowl before he reckoned it felt a bit loose at the rear. It clocked 125 mph at the end of a mile from a standing start and 135 mph on a flying mile. The test gave us half an idea about the gear ratios we’d need to run top speeds and proved that a Transit would do 140 mph with a bog-standard EcoBoost engine. Ours would end up being a lot neater job, though.

Our van, FT13 AFK, was coming along slowly but steadily, though there was a problem. North One reckoned that the van couldn’t be imported into America without a logbook, and because it was a Category B, it no longer had a valid logbook. Baker’s had finished the repairs on the van and done a perfect job of it. The TV researchers found out that they could have the van rebuilt, then inspected, and pay for an engineer’s report to prove the van was as good as new. Spellman had to smooth it out with the insurance company, who’d already sent me a cheque for the written-off Transit. It would have been a lot easier to start with a different van, but then it wouldn’t have been mine and I wouldn’t have been as into it. The engineer’s report did the job and Spellman got the van reclassified from Category B to C, meaning we could use the van for the project. Another hoop had been jumped through.

Dan and Craig from North One had been contacting parts suppliers to see what they could get in time for the project. The timescale for something as complicated and oddball as a 175-mph Transit van was dead tight, and some of the specialist companies they got in touch with were too stacked out to help. Eventually, with only about three months before it would have to be shipped out to America, Krazy Horse could really start on the spannering.

At first we were going to use the engine out of the Tourneo, but it was a really early prototype engine and nothing else we planned to use wanted to fit it, so Dan decided we should start from scratch with a different motor. Because he was talking to loads of different parts suppliers for the van, through this man and that man, a deal was done with Radical to supply an engine and other parts.

Radical are a sports car company based in Peterborough. They started in 1997, making track cars powered by superbike engines. The cars were for keen track day drivers, very lightweight, dead revvy and adjustable, so they were more like proper racing cars than modified road cars. And because they had motorcycle engines and fibreglass or carbon-fibre bodywork, they had good power-to-weight ratios. From very early in their history, Radical organised their own race series for owners, and they quickly started exporting around the world.

The company kept adding models, eventually making a road-legal car, all the time with bike engines, then, in 2005, they started using the Ford V8 engine in their SR8. That car – it looks like a modern Le Mans racer – holds the production-car lap record at the Nürburgring Nordschleife, the place I’d still like to go back to with a trick motorbike for a crack at the lap record. It’s on the list. By the time they got involved with our Transit project, Radical had built over 2,000 cars in their 19-year history.

The engine they promised us was a twin-turbo V6 EcoBoost, and supposedly good for 700 horsepower. If you’re not familiar with horsepower figures, a 2015 Ferrari 458 only makes 562 horsepower, while a 2015 Porsche 911 Turbo is 572 horsepower.

By the middle of February, FT13 AFK was returned to Krazy Horse with the front half of a steel roll cage that had been fitted by Safety Devices. Think of a roll cage as a strengthening skeleton that fits inside a vehicle. Formula One and Le Mans ‘prototype’ racing cars are designed to survive very fast crashes, but road cars and vans are only tested up to a certain speed. If they’re then converted for racing they usually need extra crash protection. Our roll cage is made from steel tube, about the same diameter as a scaffold pole, welded together and then welded to the van’s chassis.

Safety Devices made a rear roll cage that would also be used to mount the much-improved suspension to. The standard Transit has a leaf-spring back axle, but because we were increasing the power so much we needed a different set-up, and we used a four-bar linkage. The leaf spring is fine for regular van work, but Dan felt our Supervan needed something more sophisticated that would be able to deal with high-speed cornering. The van would be lowered about two inches and set up a lot more level than a regular Transit. As standard, the rear of the Transit sits higher than the front, so that when it’s carrying a load it’s not driving around with its front end in the air.

With the four-bar set-up you have a swingarm with tie-bars connecting it to the chassis of the van. The tie-rods are connected to coilover units – where the spring coil is over the shock – that supply the suspension and damping. Even though this is a conventional set-up for some modern cars, we had nothing to mount the top of the shock to because the Transit was never designed to have it. Dan cut the front suspension turrets out of the Tourneo and made them into top shock mounts for the rear of our Transit, and these were incorporated into the roll cage. Safety Devices also strengthened the chassis behind the dash so the van almost had a space-frame chassis, making it stiff and safe. It’s trick.

While the chassis was being modified, Radical were fettling the new engine. They fitted Carrillo con rods, JE pistons and their own inlet manifolds. Twin Garrett GTX2871R turbos had been sent to Radical to fit to the 3.5-litre EcoBoost V6. Radical had tried to get a Quaife gearbox sorted but there wasn’t time to make it, so we had to settle for the donor ’box from the Tourneo, which was out of one of Ford’s American pick-ups.

Back at Krazy Horse, a rear wing from a Le Mans car had been supplied by Wirth Research. I met two of their design engineers, Adam Carter and Stuart Ciballi, who had both worked for F1 teams before joining Wirth. They had done some computational fluid dynamics simulations, where a computer program predicts the flow of air over an object – in this case my van. They advised us to mount the wing in a specific position and angle. They also supplied mounts to withstand 700 kg of downforce. The point of the wing was to stick the van to the road at high speed, but there was the potential for so much downforce that we’d need to bolt it to extra strengthening mounts welded on the inside of the back doors, or they’d buckle when the van really got shifting and the aerodynamic force started pushing the van on to the road surface.

I had a go in Wirth’s race simulator to get a feel for driving fast. I’ve owned a few fast cars, done a Caterham race and a few track days, and the Volvo, my turbo six-cylinder Amazon, has taught me a few things about driving quickly, but I don’t think I’m Lewis Hamilton.

Dan built a frame for the front air dam and sent it to motorsport bodywork specialists KS Composites in Leicestershire, who covered it with Twintex, a flexible material that’s summat like carbon fibre, but more flexible. The front air dam is basically the front bumper, but Wirth suggested the shape that would work best with the aerodynamics of the van. It had to have an opening for the radiator and turbo intercoolers, and that opening was made bigger later.

Before the brakes and suspension had arrived, the TV lot needed a mock-up of how the van would look so they could get approval from the EPA, the Environmental Protection Agency, to enter the US for the race. Dan covered the framework in cardboard and duct tape, put the wheels and old suspension on and painted the lights to make it look as much like a racing car as possible. North One took photos and sent them off. The van needed a visa to get into the USA, and I did too.

I had to visit the American Embassy in London with Andy Spellman, getting there at eight in the morning and waiting in line. There aren’t any specific appointments – it’s first come, first served. I was called to the window and asked what I did for a living. I told the fella, like I tell everyone, that I’m a truck fitter, but this wasn’t what he wanted to hear, because I was applying for a work visa to make a TV programme. I was told to sit in a corner and wait. So I waited. And waited. Then I got a call from Spellman, who was waiting outside, asking what was happening. A short while later my name was called and I got told that everything had been approved and I’d be given the work visa I needed to go to America and film the programme. Spellman had pulled some strings. I’ve no idea what he did or who he spoke to, but I’m glad he did.

By now the van still looked a lot like mine from the outside, but it was totally different under the skin. As well as welding in the front suspension turrets from the Tourneo, Dan notched the chassis rails so it could be converted to rear-wheel drive. The standard petrol tank wasn’t up to the job, so two 120-litre ATL racing-car fuel cells were fitted in the back. The brakes were converted to CompBrake 350 mm discs with 6-piston calipers and the wheels were M-Sport OZs. The organisers recommended a tyre-pressure monitoring system to give an early warning of a tyre going down, before it blew out, and Dan arranged for bf1systems to fit one. Also on the safety side of things, a Lifeline automatic fire-extinguisher system was fitted. It had Cobra racing seats and Schroth Racing harnesses and HANS systems. The Transit really was short of nowt.

The Tourneo was left-hand drive, but my van was regular UK right-hand drive, so Dan had to muck about swapping over the power-steering gubbins, then the van went off to Demand Engineering in Stowmarket for new turbo headers and side-exit exhausts. There were probably two-dozen companies involved in converting the van.

Because it was a bit of a rush job to get the van ready in time to go out to Nevada for the race in May, we only had one chance to test it in England, and I put a spanner in the works by cocking up the diary dates and forcing Krazy Horse and Radical to get the van ready a day early.

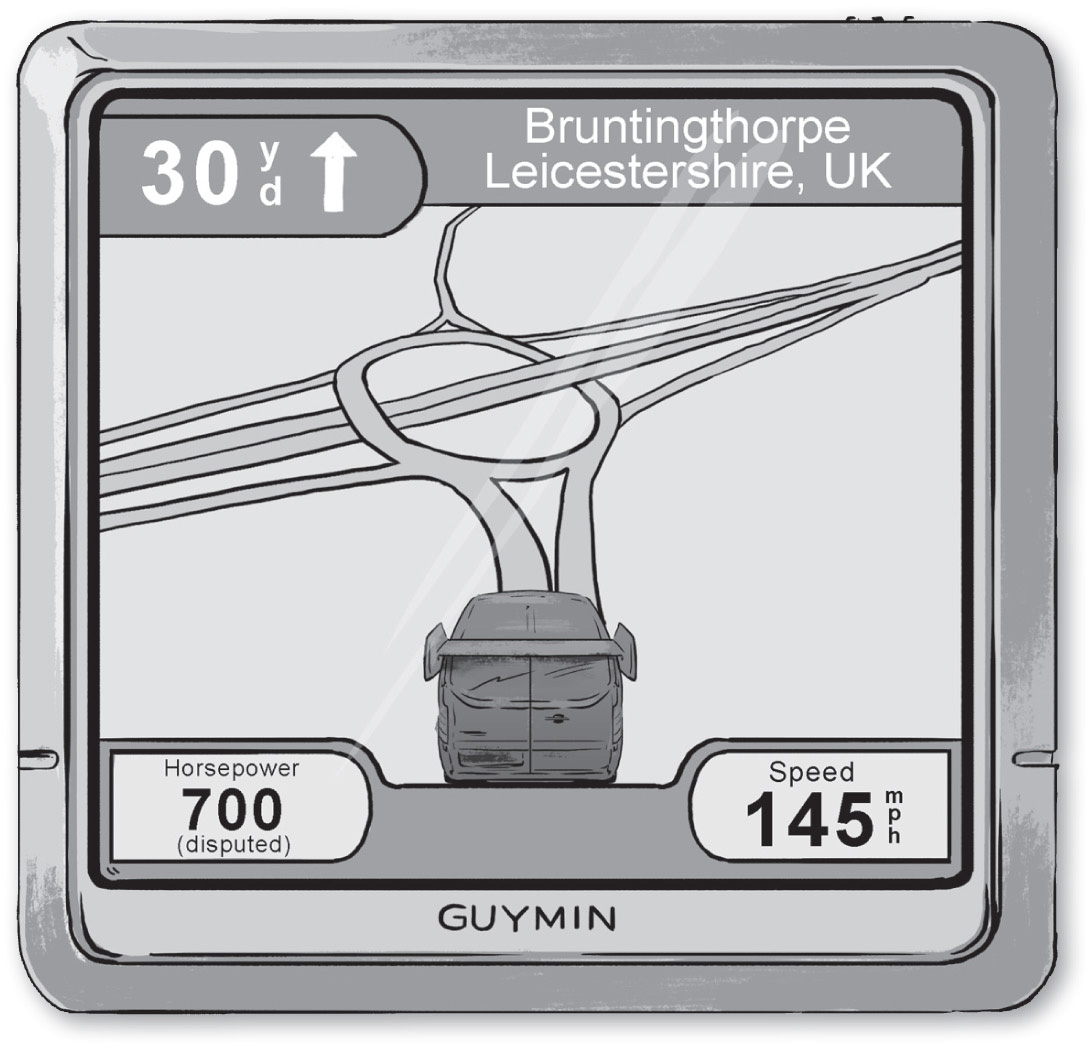

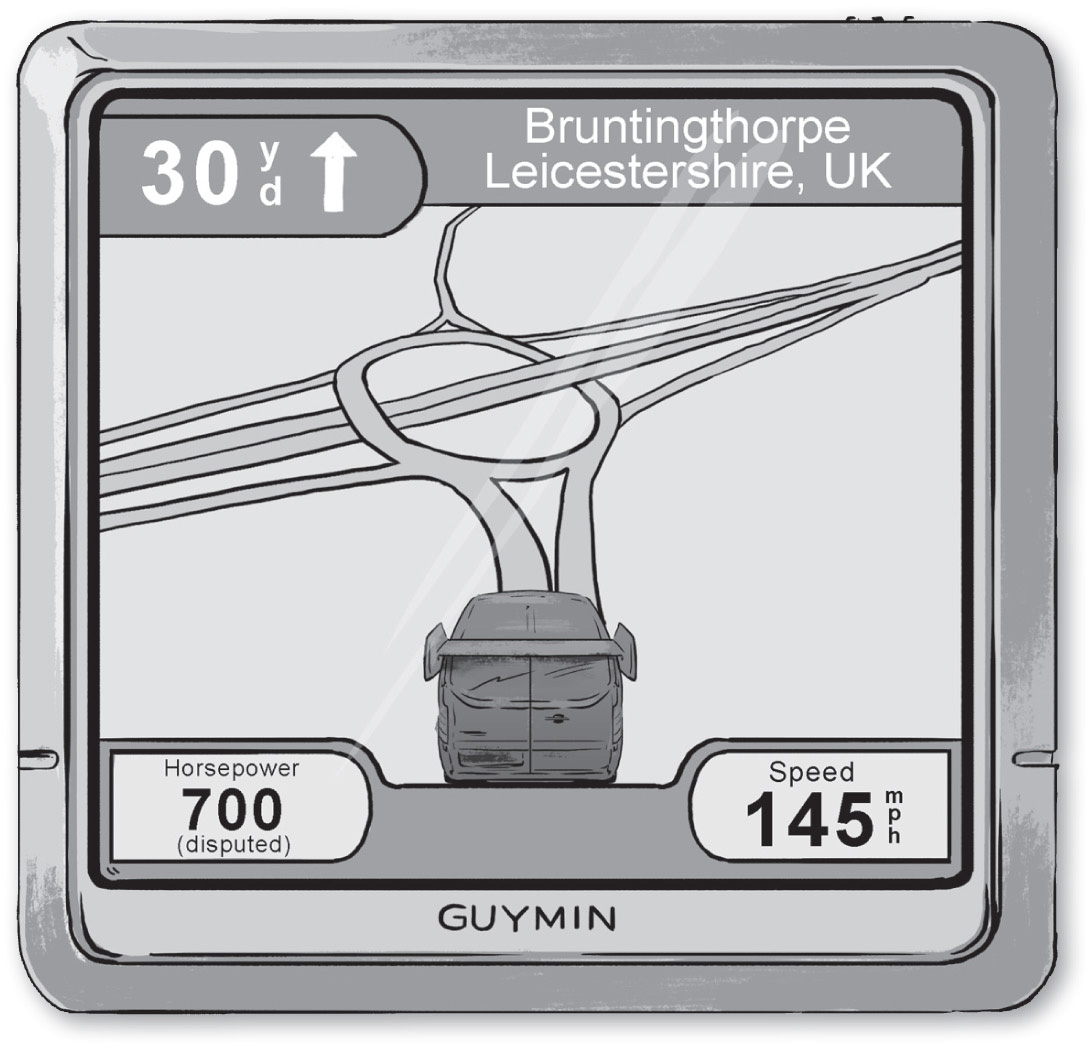

The test was planned for Bruntingthorpe in Leicestershire, a privately owned former airbase that was now used as a proving ground by manufacturers and magazines. It has a runway that’s nearly two miles long, so it’s about the best top-speed test track in Britain. But I’d double-booked myself for the Friday test day. I’d entered the Scottish two-day Pre-65 motorcycle trial, being held in Fort William at the back end of April, thinking it was a Saturday and Sunday, but it was Friday and Saturday. I’d been asked to ride it by the folk at Hope, who were one of the event’s sponsors, and didn’t want to miss it, so the TV lot set about changing everything from Friday to Thursday. It was my fault this time. I couldn’t blame anyone for writing it in the back of my diary when it should have been in the front. Bugger. My cock-up meant Radical would lose a day of fettling when they were already up against it. And the whole job was behind schedule anyway, so it was now too late to put the van in a container and ship it out to America. It would have to be flown to Las Vegas, a bloody expensive way of going about things.

After we finished filming, I got back in the hire van (my grey Transit was in for repairs) and drove to Bruntingthorpe. I got there just before midnight and kipped in the front of the van, happy to sleep there instead of mucking about getting a hotel.

My mate Dobby knew I was testing the Transit, so he took a day off work and drove down in his own Transit and we had an early-morning fry-up in the Bruntingthorpe café.

The van was supposed to be there at eight in the morning, but it wasn’t. It turned out that Radical had been running the van on their dyno overnight before the test to start setting up the fuelling maps, but they reckoned that the heat in the dyno room had cooked the starter motor. The test was postponed until midday, but then the oil cooler split as they were loading the Transit on to the transporter to leave Peterborough. They finally got it sorted at two in the afternoon, but were still about two hours away, so we mucked about until they turned up. Dobby was in his Transit Custom, Nat the cameraman had his Mercedes Vito 116 that he thought was rocket-fast, and I was in a hired Vauxhall. We had the two-mile runway to ourselves and nothing else to do until the souped-up Transit arrived from Radical, so we started racing our vans. I’d never do it in my own van, but as it’s a rental, let’s go mental! Dobby’s was the quickest. It would do 105 mph before the speed limiter cut in. Then Spellman came in his M-Sport Transit. His had similar acceleration to Dobby’s up to 105, but, because his speed limiter had been taken off and the engine remapped to give more horsepower, it would keep going until 115 mph.

Eventually, we got a phone call saying, ‘We’re just leaving,’ and I was thinking, I need to be in Fort William. Originally, I had to be in Scotland before seven on Thursday evening. I explained what was happening and they said they’d let me sign on the next morning, but I still had to get to Fort William, and that was seven and a half hours away on a perfect run without stopping.

The Transit finally turned up at about half-five. From the outside it just looked like my van, but with black wheels and a big wing on the back, which is good because I didn’t want it to look all Carlos Fandango. The starting procedure was totally different to the last time I’d driven it too. I had to turn the ignition on, to energise everything, then flick the master switch to turn the ECU on, then switch the fuel pumps on, before pressing a button to start the engine.

I started testing the van and soon worked out that the two-mile runway was long enough for it to rev out in fifth gear – when I put it into sixth the power just died. It didn’t feel like a 700-horsepower motor to me, but that could’ve been the gearing making it feel that way. There was a massive gap between fifth and sixth gear – I’d lose 2,000 rpm changing up, so the motor would drop out of the boost and lose all its momentum, meaning I had to shift down again. I was left thinking, Well, that isn’t fast enough. I knew how much work everyone had put into it all, but I was only getting 145 mph out of the twin-turbo, 3.5-litre V6, and I wasn’t very impressed.

In the 150 mph class of the Nevada Open Road Challenge you aren’t allowed to drop below 145 (after getting up to speed) or go faster than 165. So, obviously, the Transit had to do more than 150 to average that speed, when you take the standing start and corners into the equation.

Still, the fellas from Radical weren’t panicking. They were just saying, ‘Well, we’ll give it more boost,’ and I thought, But it won’t pull top gear. Why don’t you muck about with the back axle ratio? (This is a bit like changing the rear sprocket on a motorbike.)

After a couple of hours in the van it was time to call it a day. The Transit was loaded back on to the transporter and I headed off to Fort William. I ended up going Stoke way, up the M6, M74 and A9. The A82 around Loch Lomond was closed overnight, so I had to go right up the other side of Scotland. I bet I was only 60 miles short of Inverness before I turned towards the west and started heading back down towards Fort Bill. I got to the A9 and it was snowing like hell and settling, so I had a couple of hours’ sleep in the van, near Stirling, and got to Fort William at five in the morning. I had another couple of hours’ sleep in the van, then went to the B&B, had breakfast with the lads from Hope and rode the trial.

How did I do in the trial after all that? Shit.