I’D ONLY BEEN back for a couple of weeks before I was heading to North America again for another time trial, this time a bit longer and a lot slower. The Tour Divide is called the world’s toughest bicycle race and stretches from Banff in Canada to Antelope Wells on the Mexican border. The race has been described as an extreme test of endurance, self-reliance and mental toughness. And it sounded a bit of me. There are no entry fees, no prizes and no sponsors. It’s purely amateur.

I was told about the race by Stu Thomson. In January 2011, I’d done the Strathpuffer, the 24-hour mountain bike race held up in the north of Scotland, and two weeks later I was out in Oman doing a different kind of mountain-bike race, a four-day stage race, the Trans Hajar. It was a lot different to what I was used to. The Trans Hajar was short days at a very fast speed, and I had to turn myself inside out to be anything like on the pace, because it was more like sprinting. I’m more like a 24-hour slogger, but I was right into it. Stu is best known for making Danny MacAskill’s world famous bike-stunt videos, but he’s done other stuff, including some music videos. Stu was there, wearing two hats, filming for Orange, the British mountain-bike company, and for the race organisers, the Oman government and tourist board. His film was all about the race, and because I was taking part in it, he was filming odd bits with me.

At the end of the race he told me to let him know if I ever wanted to film anything with him. I said if he came up with some oddball ideas or something that had a good chance of breaking me then I’d probably be up for it.

A while later he rang me and said, ‘Right, I’ve found something. There’s a mountain-bike race in America, the longest in the world, this many miles, got this much climbing. It’s called the Tour Divide.’ That was the first I’d heard of it, and I liked the sound of it. We didn’t speak about it a lot, just odd bits, but it was a fair topic for a year. We’d talk on the phone every couple of months, and he sent me a couple of videos, but I soon realised it was the same time as the Isle of Man TT, and that meant I wasn’t going to be able to do it for a while, because the TT was the middle of the racing year. Even if I wasn’t enjoying it as much as I used to, everything before the TT was building up to it, everything after was the slowdown. I was in that rut. While the TT wasn’t the be-all and end-all, like it had been for me in 2006, 2007 and 2008, it was still important. But the seed had been planted, and I loved the sound of the Tour Divide.

I was enjoying the Isle of Man TT less and less every year. It seemed like it was getting buried under more people, more bullshit, more mither. I still loved the racing, but it felt like it was harder to dig down to that through everything else. I enjoyed the 2015 TT, because I stayed out of the way and I had the dog out there with me, but I still drove home after the fortnight was over thinking, What am I doing? I wasn’t there to make up the numbers. I’d gone faster than I ever had before, with a 132.398 mph lap in the 2015 Senior, and on the podium in the 600 race. So I was licking on, but I’d probably rather have been at work. There were good bits. I got to ride my bike around the TT course and walk my dog in the hills and go pushbiking, but I was going through the motions. I’d done it for years, and even though it’s the Isle of Man TT, it’s still only a motorbike race.

The rest of the year was more of the same. I did some Irish national races, the Southern 100 and then the Ulster Grand Prix, where I spannered myself. While I was in that Belfast hospital for a week, I thought, I know what, I’m going to do that mountain-bike race next year. The decision was made as I lay there, bollocksed. It might have been because I knew I could, very easily, have been stuck in a bed paralysed, waiting to be spoon-fed my next meal. It was a big crash and I’d broken my back again, so it didn’t take a great deal of imagination to wonder what might have been.

I went back to work and started telling people that I was going to miss the TT, to do this mountain-bike race. Most people thought it was a good idea. I told Philip Neill, the boss of the TAS racing team I’d been with since 2011, so he could look for someone to replace me. By the end of the year, I knew that it would take so much to get ready for the Tour Divide that I didn’t want to risk getting an injury racing a motorbike in the build-up. If I broke or even twisted something it would knacker my training up. From the Ulster in August 2015, to June 2016, I hadn’t raced a motorbike, but I wasn’t missing them, because I was still doing plenty with them, especially with the wall of death. It was different to racing, but that wasn’t a bad thing, and training for the Tour Divide was taking up every bit of spare time and thought.

I spoke to Stu Thomson and Jason Miles about making a programme about the Tour Divide, but in the end it didn’t feel like the right thing to do. I reckoned that filming and becoming more recognisable from the TV stuff had buggered up my enjoyment of being at motorcycle races, and I didn’t want to risk the same happening with bicycle races. I like it just as it is. It’s my thing. And now, looking back, I’m pleased I didn’t go along with the idea of filming it.

So, by Sunday afternoon, 5 June, the training was finished and I couldn’t do any more. I had bought and modified a bike for the job with help from a mate, because I was busy with the wall of death bike. I was booked on a flight to Calgary, Canada, with the return flight from Phoenix, Arizona, a couple of thousand miles away.

I’d spent the Friday before sorting the last few bits, and I had nothing left to do on Saturday. I was sorted. The bike was packed, everything was done. Jon from Louth Cycle Centre had originally built the bike and I’d got it back to mine and done a few things. If it wasn’t for him, I’d have converted one of my 24-hour race bikes for it, but he had the proper thing, a Salsa Fargo. It’s a cheap bike, about £800 or summat, but the bloke who held the Tour Divide record, Josh Kato, used the same Fargo frame when he set his record time. We upgraded a load of stuff, though, fitting some suspension forks, a Rohloff hub in the back and a dead fancy dynamo front hub to power the lights and recharge my satnav. This Salsa had been in John’s shop for years. It’s a bit of a strange bike – it’s neither a road bike nor a mountain bike, but it has mountain-bike tyres.

When the day arrived, Sharon took me to the airport in the Transit. I lifted the bike out of the van then said, ‘See ya, lass.’ I’m not one for big, emotional goodbyes. I’d see her in three weeks in New Mexico, all being well.

I flew out economy class. I was thinking about upgrading, but I didn’t ask the price, so it never got to more than thinking. You still get to the same place at the same time, however much you pay.

I landed in Calgary at nine or ten at night, got my bike on a trolley and just had my Kriega backpack with my riding shoes and helmet in it on my back – that was it as far as luggage. I was wearing some knackered old trainers, because I knew I would have to leave them. I wasn’t going to carry anything I didn’t need to.

Now it was me, myself and I, alone, and I began to realise that the racing and the TV work has made me soft. There was no one telling me, ‘Right you need to be here at this time, you need to be there at that time,’ like I’d got used to. Even the Pikes Peak and the Transit jobs were like that. There’s a bit of work on my part, but it’s all organised. For the last eight or nine years, since I left Team Racing and joined AIM Yamaha, even when I went racing I’d go and sign on, and then the bikes, tyres and fuel were all sorted. I just had to ride the things. When I was building the wall of death bike I had to organise and make a load of bits, and go on a course to learn how to CNC program, but it was only bits, not the whole job. This was different, though. The Tour Divide was all on me. I had to get all the way down the Continental Divide to Mexico, not really knowing owt except the bits I’d read in books and watched in a documentary.

The last bit that had been sorted for me was a nice hotel in Banff, the mountain holiday-resort town the race starts from. Spellman had booked that. I checked in late Sunday, early Monday morning after getting the bus for the two-hour journey from Calgary airport. The next day I bolted the bike together, as it had been partially stripped to fit in the special travel bag. It was packed with all the specialist luggage strapped to it, and everything I thought I’d need already in the bags. Next I started on the list of jobs I’d written for myself. I had to get some salt tablets, energy bars and a pair of short, lightweight socks. I had travelled out in winter ones, but my feet were sweltering on the plane, and it got me thinking about the deserts I had to ride through, so I reckoned I needed an option.

I didn’t have to sign on with anyone because there’s no one at the start and no one at the finish. It’s an underground race and they want to keep it that way. I don’t think they would take kindly to people going and filming it (though they filmed it in the past to help get it off the ground), so that was another good reason for us not to. There’s no reception for the racers, no welcome packs, nothing. All you do is go online to register your SPOT Tracker the day before you plan to set off, and that tells the organisers where you are and how long it’s taking you.

The SPOT Tracker is about half the size of a smartphone. It has an orange rubber casing to survive a few hard drops. It’s a device that can track your route and send messages to pre-set numbers or addresses. It doesn’t rely on mobile phone networks, it operates purely by satellite, so as long as it can see the sky it can send a message. All sorts of folk use them: mountaineers, off-road motorcyclists, hikers, light-aircraft pilots. The SPOT Tracker doesn’t have a screen, just a few buttons. One has a small hand reaching for a bigger hand, which sends a signal saying, ‘I’m in trouble, but I’ll sort it out.’ You have to lift a rubber flap to get to it, so you can’t push it by mistake.

There’s another button, with SOS on it, and if you press that you’re telling the emergency services, ‘I’m fucked!’ and they send GEOS global rescue to come and get you wherever you are in the world. Then send you the bill. When I signed up there were only six places in the world that the GEOS rescue folk wouldn’t cover – Afghanistan, Chechnya, Democratic Republic of Congo, Iraq, Somalia and Israel. I’d be well off course if I found myself in any of them when I was thinking about pressing the button.

There’s a speech-bubble button that sends a pre-set message to up to five numbers that you put in there, but you had to pay extra for it, so I didn’t bother. You have to pay a year’s subscription, but you can choose different levels of coverage and I got the lowest one, so not all the buttons on my SPOT Tracker did owt. There’s a button with a tick that sends a confirmation whenever I press it, to say, I’m OK. I sent that to Sharon, my sister Sally and my mate Dobby. I don’t really know why Dobby, but he wanted to know and he’s a good mate.

The other important button has a shoe print on it. You press that when you first set off and it starts the SPOT Tracker sending a signal every ten minutes, tracking your speed and position on a map, without you doing anything. That’s what they use to put you on the map on the Trackleaders website. All I had to do was keep it charged up and not lose it.

Banff didn’t look like it was full of dead-fit athletes, but I think that’s because I arrived early and anyone else taking part hadn’t got there yet. There was one bloke in my hotel who was sat on his own as well, legs shaved, head shaved, lean as hell. I heard him talk to someone and he was British, but I didn’t try to make conversation with him. I like my own company and I knew I was up to the job, so I didn’t need to speak to anyone to suss the landscape.

Because of the way the cheap flights I’d booked worked, I flew out on 5 June and I was supposed to fly back on 29 June. I felt I’d done everything I could with the training, but I knew that not many folk had completed the ride in under 20 days – fewer than 50 in total – and it was already at the back of my mind that I didn’t want to miss the flight home. Sharon had got hold of Matthew Lee. He is one of the most experienced riders, and he sets the route and gives people advice. He’s just a brilliant bloke. Matthew was featured in a film of the 2008 Tour Divide I’d watched, called Ride the Divide. He had held the record for the course, setting it at 19 days, 12 hours in 2008. He broke his own record in 2009 and improved on it again in 2010, lowering it to 17 days, 16 hours and 10 minutes. Since then it had been broken in 2011, 2013 and 2015, with Josh Kato, from Washington State, holding the outright record at 14 days, 11 hours and 27 minutes going into the 2016 race. Bethany Dunne has the best ever women’s time at 19 days, 2 hours and 37 minutes, nearly 10 hours quicker than Matthew’s record time in 2008.

Friday 10 June would be the Grand Départ for the 2016 Tour Divide, the Grand Départ being the name for the official group start they use in the Tour de France. I was told that the British weekly motorbike paper Motorcycle News had contacted the organisers to find out when I was leaving and work out who could interview me and take photos at the start, and I didn’t want anything like that. I also couldn’t understand what me taking part in a bicycle race in North America had to do with motorbikes and MCN, so I entered and registered my SPOT Tracker under the pseudonym Terry Smith.

Sharon explained to Matthew Lee that I wasn’t bothered about being part of the race – I just wanted to know how long it would take me to do the ride – and he emailed back saying I could set off at any time between June and September and my time would count, but I wouldn’t get a finishing position in the race if I didn’t leave with the Grand Départ. I wasn’t bothered about that. I just wanted a time for myself, and to know I could do it.

So even before I left England, I told Sharon and Spellman that I was going to set off earlier in the week. I thought Wednesday morning would be best, giving me the chance to get over the flight and have a couple of good nights’ rest before leaving, but by Monday afternoon I’d done nearly everything I needed to in Banff, and as beautiful a place as it is, I was itching to go. I could have sat there, drinking posh coffee for a few more days, but I couldn’t settle.

On Monday afternoon I biked up to where the race would start from, the beginning of the Spray River West trail. It was no distance out of town, but it still took a bit of finding. I thought there might be something to tell me that this was the start of the Tour Divide route, but there was nothing. There was just a regular kind of wooden sign for the trail and a noticeboard with glazed doors on it, like you might have outside a village hall or a church. I knew it was the right place, though, I’d put the route in my Garmin GPS unit and it confirmed I was at the start, and also that I was 4,500 feet above sea level.

There was an old boy, in his sixties, out for a ride on his bike. He asked, ‘Are you doing the Tour Divide race?’ I told him I was, and he said, ‘That’s a big job, that,’ before explaining that he was a physical trainer. I told him that I wanted to stay out of the way of all the bother and I was going to leave on Wednesday. He said, ‘Why don’t you set off tomorrow?’ And I thought, Yeah, why don’t I?

On my way back to the hotel I pedalled to the post office to find out how much it would cost to send the brand new bike bag back, and they told me $400. The bag was good, but not that good, so I left it with the lass at the post office and had her promise me it would go to a good home. I could have sent my bike out in an old bag but it was important that it arrived in one piece. I’d got a really good bag to protect the bike, and it broke my heart to leave the brand new luggage behind.

I asked a passer-by if they knew anywhere to get my hair cut and they pointed me around the corner. The lass who cut it was real cool, red hair, loads of tattoos. She reckoned she’d only just started talking English, because she’d moved from Quebec, the French-talking part of Canada. There was a lot of hair to get rid of, so I just asked her to lob it off. I told her what I was up to, but I wasn’t making a big deal of it and I’m not sure she grasped what I was doing.

That night I had a big feed of steak and salad in the hotel, then went to the bar and had a couple of pints. I like sitting in bars on my own. I reckon if I was in a bar with someone and saw a bloke sat alone I’d think he was a bit strange, but I like it. I was weighing the job up, knowing it was the biggest thing I’d ever undertaken. I’d done a fair bit of reading on the subject and plenty of training, but it was still a ride into the unknown. And I liked that about it too.

It’d have been about ten o’clock on Monday night by the time I’d supped up. The hotel computer was downstairs, next to the Coke machine. I went on to the Trackleaders website and put in my start time, nine o’clock Tuesday morning. Now I was registered, the organisers, and anyone else who was interested, could follow my progress at any time.

I wanted to catch up on sleep before I set off, but I woke up early on Tuesday, before six. I couldn’t sleep. Nothing had made me nervous like this for years. I’d done three-day rides. I’d done quite a lot of tough 24-hour stuff. But not 2,745 miles. Sharon was confident I could do it, so was Dobby, Spellman and a few other mates, but there was still doubt in my own mind.

I folded up the T-shirt I’d flown out in and left it on top of the old trainers I was leaving behind. Even after loads of breakfast I was still ready to go at half-seven. I rode to the start, 15 minutes away from the hotel, waited until exactly eight on my Garmin and set off. It didn’t matter that I’d said I was leaving at nine, because the SPOT Tracker would pick up on it.

It was a beautiful day as I pedalled off on the first mile, thinking, Only 2,745 of these to go. I like looking at things in fractions. Soon I was a thousandth of the way through it. I never thought, Oh, I can do this. I had read that I had to take every day as it comes. Even the fittest folk get injuries that stop them completing the race.

I found it a bit difficult to pace myself on the first day. The temperature felt in the mid-20s and it was perfect biking weather. I was ten hours in and thought I was doing alright. I had one book with me, Cycling the Great Divide: From Canada to Mexico on North America’s Premier Long-Distance Mountain Bike Route by Michael McCoy. It’s aimed at touring cyclists, not the more hardcore Tour Divide riders, but the information crosses over. It has detailed maps of the trails and day-by-day breakdowns of what to expect, where to get food and where to camp, but because it’s aimed at tourists enjoying themselves, not masochists trying to break themselves, the route is spread over 70 days. I still wanted to do it in less than 20. And I had to do it in under 22 days if I didn’t want to miss my flight.

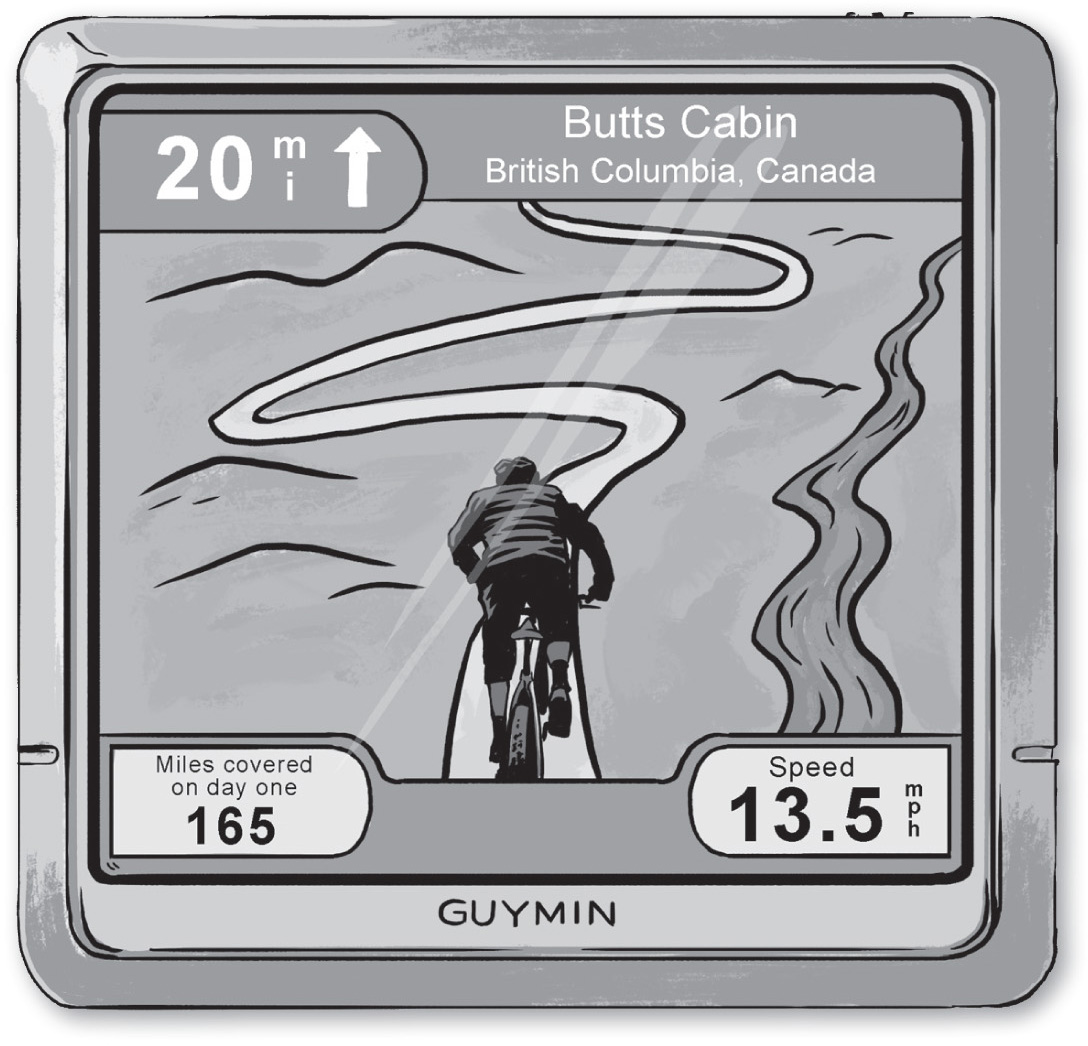

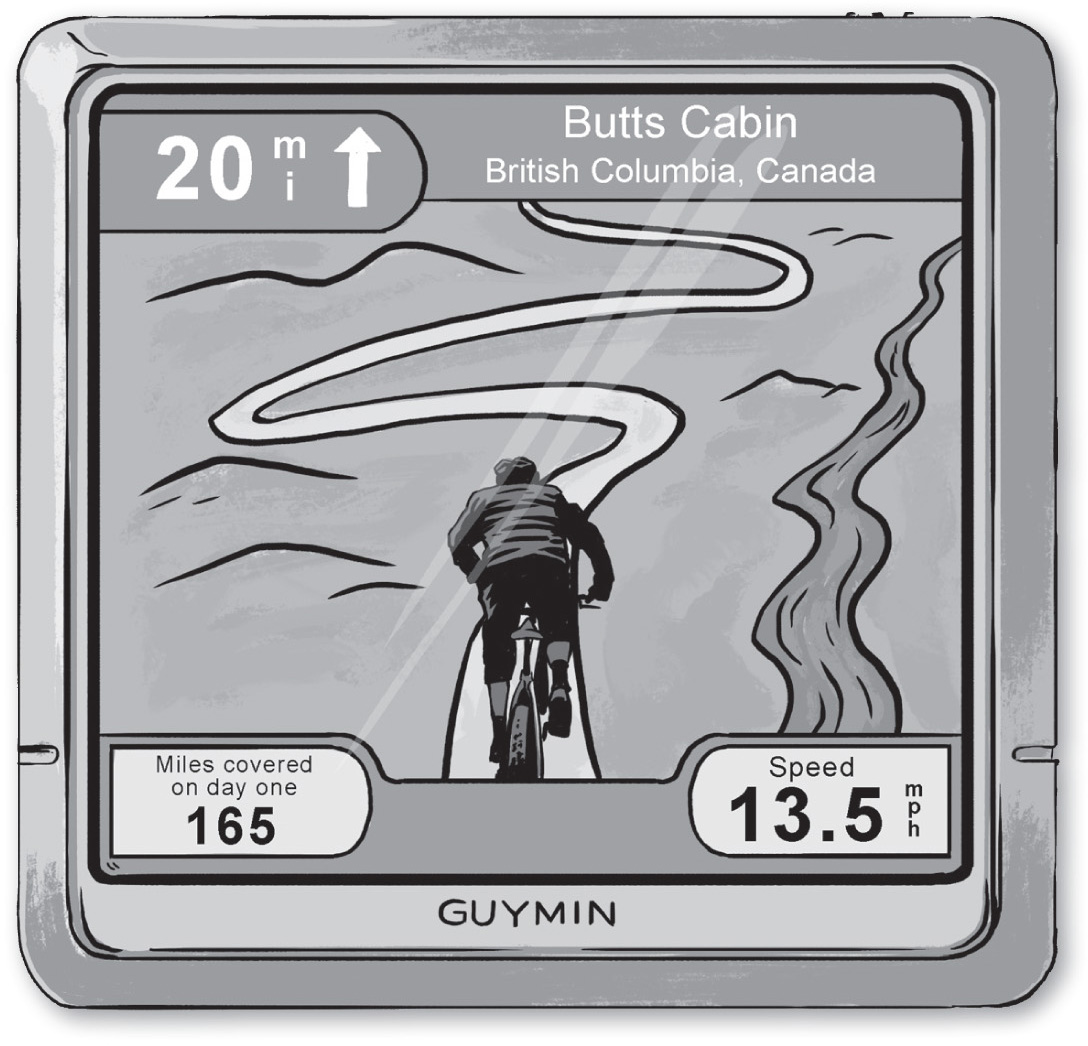

From everything I’d read about the race I knew that if I got to Butts Cabin, which is about 180 miles in, on the first night, I was doing alright, and I reckoned I might get there. I was cycling in absolutely beautiful countryside, past Spray Lakes Reservoir and Canyon Dam. I made my first crossing of the Continental Divide, which gives the route and the race its name.

The Continental Divide is the crooked line running through North America that divides the continent into two drainage areas. It runs from Alaska, through Canada, mainland USA and into Mexico and beyond. On one side all the rivers run to the Atlantic Ocean (or the Gulf of Mexico), and on the other they run to the Pacific. The Continental Divide follows the Rocky Mountains, which was why I, and all the other Tour Divide riders, had the equivalent of seven Everests’ worth of climbing between Banff and Antelope Wells.

I climbed up to 6,443 feet at Elk Pass and followed the Elk River. I went through the town of Sparwood, British Columbia. If I had been following the suggested daily mileages in my guidebook, I’d have been at the end of day five already, but I hadn’t even stopped to eat. I changed that in Sparwood, pulling up at a petrol station with a shop attached to it and loading up with cinnamon rolls, doughnuts, full-fat milk and Gatorade.

I was following my Garmin, and the trail was fairly obvious a lot of the time, but because I hadn’t downloaded the USA map background on to my device it just showed a line, and me as a dot on it. It didn’t show any other references like lakes, rivers or mountains, so it wasn’t always totally clear. The whole route was marked out using 10,000 waypoints, so at times the detail wasn’t that fine, but I’d thought I’d be alright. I should’ve spent the money on the US map to load into it.

I knew that I shouldn’t ride until I couldn’t pedal any more before deciding to stop for the night. I was only 20 miles, if that, from Butts Cabin, and anyone who is going to do the winning is always at Butts Cabin on the first night. But by that point I was thinking to myself that I was in such a beautiful country, and I’d already seen so much memorable stuff, that I was just going to ride the Tour Divide and not race it. I wouldn’t hang about, but I wouldn’t kill myself to try to get close to a record time.

I stopped at 11 o’clock at the end of the first day. I’d covered 165 miles, about 16 per cent of the overall route, and it had been an easy enough day to start off with. There had been a little bit of tarmac road, but it was mainly off-road on broad gravel tracks with plenty of climbing, much more than I was used to. There had been nothing daft and I was averaging 13 to 14 mph, which was some going for a bike that weighed 25 kilograms with all my kit on it.

Day one was over and I was loving it. I’d been soft for too long. Nothing was going to be soft for the next 18 days.