NEVER HAS SO much piss been sent into the wind. Trying to break the world record for human-powered watercraft was another project for the 2016 Speed series. The series was four programmes long and split down the middle, half human-powered, me being the human, and half involving big turbo engines.

The record we were chasing belongs to Mark Drela from the American university MIT, the Massachusetts Institute of Technology. His speed was 18.5 knots, the equivalent of 21.3 mph. It doesn’t sound that fast, does it? But Drela is not a messer. He’s a professor specialising in the aeronautical and astronautical side of things, with a bit of fluid dynamics chucked in for good measure.

I looked him up, and the MIT’s website has a page on him describing what he’s up to. Here’s a bit of it: ‘Current research involves development of computational algorithms for the prediction of 2D and 3D external flows about aerodynamic bodies. Subsonic, transonic, and supersonic flow regimes are being considered. Most of the work centers on viscous/inviscid coupling schemes in conjunction with direct Newton solution methods. Two- and three-dimensional integral boundary layer formulations are also being developed for modeling viscous regions.’

Exactly. But we had some brains involved in our attempt too. Lincoln University had set their students a project to design a potential record breaker, and they’d got in touch with North One to see if there was any interest in working together. One of Lincoln’s professors, Ron Bickerton, was our main contact. He’s in his sixties, with a long grey ponytail, and lives on a boat when he’s working at the university.

For the first day of filming, we met on Ron’s boat at Burton Waters, near Lincoln. He told us what the students had been up to and showed us footage of the current record being set.

When I thought of human-powered watercraft, I pictured a swan pedalo on a boating lake. And it sounded like what we were doing was building a glorified pedalo. I hadn’t had that much experience with pedalos, but I’d had enough. I’d hired one in Croatia once. It had a slide on the front. It was trick.

Mark Drela’s record breaker was called the Decavitator, and it was a pedal-powered watercraft with a big propeller on the back like one of those airboats they have in the swamps of Florida. The YouTube clip of it in action didn’t look that impressive, initially, then I kept watching it and realised that Drela, who was not only the designer, but was also pedalling it, was licking on.

Ron was the driving force of our project. He explained that he had this man involved, and that man doing this, and that the students had all these great ideas. As time went on I got the feeling they were full of great ideas and big words, but after a while it seemed to me that next to bugger all was actually happening. I’d had involvement with universities before in the previous Speed series, and the ones that stand out the most are the projects we’d done with Sheffield Hallam University, brilliant stuff like the gravity racer, which did 85.61 mph down Mont Ventoux (before Brian the Chimp had a furry hand in crashing it) and the 83.49 mph sledge. I felt the Lincoln side fell down when it actually came to turning the great words that were falling out of their mouths into action.

The Speed programmes often involve some sort of sports science along with the engineering challenges, and this one was no different. As part of the programme I visited Lincoln University to do a load of dyno tests on a static exercise bike, linked up to a load of monitors. We wanted to make sure I could put out the wattage they reckoned we needed to produce for the machine to break the record.

Another thing North One are good at doing is getting high-profile experts to give me some advice. For this programme we had a couple of knights who have won ten Olympic gold medals between them. First, I had a day with Sir Chris Hoy in Lincoln University, then I went sailing with Sir Ben Ainslie. The cycling legend was brought in to suggest some training for a bit of TV bullshit, and what a lovely bloke. I felt a bit sorry for him, because I stunk the day I met him. I was training for the Tour Divide, and I’d set off at daft o’clock in the morning to cycle the long way to meet him at Lincoln University. I hadn’t had a proper wash for three days. I don’t get washed that often if I’m at work – what’s the point if I’m not that caked up? And I was wearing waterproofs, so it was a bit boil-in-the-bag. I could even smell myself, so it must have been bad. He didn’t say anything, though, because he’s a polite man.

It was worked out how many watts I theoretically needed to put out and for how long to have a crack at breaking the record. I did manage to make enough power, and for long enough, in the lab tests, and during the day Chris Hoy came out with some interesting stuff that wasn’t really anything to do with the programme. He explained that he was never a natural, and that kids who are thought of as naturals at school age are often winning mainly because they’re bigger and stronger, having developed earlier than most of their competition. These kids get used to winning, but when the other kids’ physiques build and strength increases, they catch up, the ‘natural’ kids start losing more than they win, and that’s when they pack in. Chris said he had to work at it, and he reckons it’s the kids who never had success, the ones who it didn’t come easy for, but they kept working at it, who are the ones to put your money on. He was one of them.

He’s the same height as me, but he’s a much bigger build, even though he said he’d lost 4 kilograms, over half a stone, since he retired from racing. He gave me some interval training tips to increase my maximum power, but nothing that would help me with endurance. I think I am what I am when it comes to endurance.

Chris Hoy came to track cycling from racing BMX. I asked if he knew Dave Maw, my mate Jonty’s brother who I mentioned in When You Dead, You Dead. Dave was three-time world champion and sadly died at a young age in a car crash. Chris Hoy said, ‘Dave Maw! Do you know Dave Maw?’ I explained that I didn’t, but I knew the family. He was a year younger than Chris, but he was winning more.

Multi-million-pound America’s Cup racing yachts are designed to be hydrofoils, like our pedalo, so the TV lot decided that it would be good telly to get me out on one of these cutting-edge boats. They sorted it for me to spend a day with the best, Sir Ben Ainslie and his whole crew.

It was another example of TV bullshit, to be out on this massive multi-million-pound racing yacht to see how a hydrofoil worked, but I wasn’t complaining, because again, what an honour and opportunity. I knew the name Ben Ainslie from hearing it on the radio, but I didn’t know anything about him. He’s won medals at five consecutive Olympic games, including four golds. He’s also won 11 sailing world championships, and he’s been awarded an MBE, OBE and CBE and been knighted. Everyone on that boat had massive respect for him, and they were all hard bastards.

It was a brilliant experience. That crew are as fit as. When you see them with their hand on the handles of a winch, spinning it like hell, it’s what they call grinding, and they’re powering everything on the boat. The rules say you are not allowed to have any stored energy on the boat, so it all must be man-powered, and that’s what the grinders do. I did a bit of it and it’s bloody hard work. All the controls are mirrored on either side of the boat, and the way it’s leaning determines which controls the crew use.

We sailed out of Portsmouth towards the Isle of Wight, and I was mucking about grinding for a bit, then they did proper race simulations. The boats lick along at 40-odd knots, which is pretty fast on water. I found out that whoever wins the America’s Cup decides when the next one is, where it is and what the rules are. There are only ever six boats, including the previous winner. The next one is 2017.

The budget of an America’s Cup team is massive. The team I was with, the Land Rover BAR team, had something like a £150 million budget. It makes MotoGP look like club racing at Mallory Park.

Ainslie is one of the most respected men in the sailing game. He was brought in as the tactician of the struggling Oracle team at the last America’s Cup, in 2012–13, after the Oracle team had lost four of the first five races, and helped them win it. From what I’m told no one had ever made a comeback like it. He’s very posh, not a messer, but all the crew were gritty bastards. We were out on the water from nine till two, then they had a training session, with a personal trainer, after that. It was all very structured.

I had a tour of the headquarters and saw they have an office full of 20 people, a lot of them ex-Formula One, most doing boat design for the team. You’d have to see it to believe it, because I’ve never seen anything like it.

Back at pedalo-design headquarters in Lincoln I saw the fancy carbon-fibre catamaran hull that had been made. The record was set using an air propeller, but the Lincoln lot decided to use a water propeller. The design of it was called a highly skewed, asymmetric prop. It was developed for submarines because it’s quieter than previous propellers. I was told that this design was also more efficient, converting more of their energy into forward motion. Ron explained all this to me and it sounded good. I was convinced.

The catamaran hull would also have hydrofoils attached. These work like a plane’s wing, but in water. The foils produce lift, at a certain speed, pushing the hull up and out of the water, reducing the drag and increasing the potential speed. Ron also had an idea to fill the centre between the two hulls, so when the hydrofoils lifted the boat out of the water there would be a ground effect helping to keep it up on the hydrofoils. This idea was used by the Ekranoplan, Russia’s experimental ground-effect aircraft. The one I’d heard of was the KM, an enormous Ekranoplan that was first tested in 1966. It’s the oddest-looking plane, with stubby, broad square wings, a massive tail wing and eight jet engines, mounted four on each side just behind the cockpit, with another two jet engines on the tail, so ten in total. American spy satellites spotted it at a test site, and after first thinking it was a half-built plane, waiting for the rest of its wings to be bolted on, they worked out what it could be and nicknamed it the Caspian Sea Monster. You look at this thing and think, Mother Mary! It was a sort of seaplane, but it only flew 20 feet above the water or ice. It was so big, and could carry so much cargo, that it needed something for the air beneath its wings to push against to be able to fly. The idea was that it could transport more weight more efficiently than traditional transport planes of the time, and it could. It was also harder to spot with radar, which was useful in those Cold War times. The Russians built loads of different prototypes, but the whole Ekranoplan idea didn’t come to anything in the end. The Caspian Sea Monster was tested until 1980, when it crashed and sunk. I was finding all this fascinating, but I still wasn’t convinced that the boat being built would be as successful as it needed to be.

The first test of our boat was at Burton Waters, where we’d met Ron to hear his plan at the start of filming. The pedalling gear wasn’t fitted to the boat yet, so we towed it with another boat to try to prove the theory of the hull. It tried coming up on the hydrofoils, which were on something like four-foot-tall stilts, but they kept breaking. They were reinforced, we’d try again and they’d break again.

Once the pedalling gear was fitted, we returned to test the boat again. The asymmetric prop had to spin at 3,000 rpm, so it needed a gearbox to convert my pedalling cadence to that huge rpm, but the gearbox was only small so that kept breaking too. Then the chain alignment was out, and it kept chucking the chain off.

It all seemed to be going tits, when a couple of Ron’s former students, Jez and Simon, who both worked for Siemens in Lincoln, got involved. Jez and Simon redesigned the gearbox, working in their sheds every night. They made it all work, but the concept was fundamentally flawed. Really they just shined the shit.

When we visited Ben Ainslie’s America’s Cup design office, we showed one of their designers photos of our boat and he wondered out loud, ‘Why haven’t you used an air prop? Why do you have two hulls instead of one?’ We didn’t really have an answer – it was what Ron and his students had decided.

James Woodroffe, one of North One TV’s executive producers, took all this in and, when the Lincoln boat was looking like a shower of shit, he decided to put a plan B into action. He contacted a bloke called Mike, from down Bristol way, who designs and builds racing Moths. These are small, single-hull sailing dinghies that use hydrofoils. James arranged for a single-hull boat with an air propeller to be built. If nowt else we could compare the two concepts. Mike was a real switched-on lad, younger than me, and he assembled his version of the potential record breaker in my back garden.

As the record-attempt day drew closer I met with the Lincoln lot at Burton Waters for extra tests when the cameras weren’t there, because I was that into it. I’d been down a couple of nights after work and a couple of Sundays too – I don’t want to just rock up on a filming day – but we were still way off the record. I would power this boat lying in a recumbent position, so legs out in front of me, lying back, not a regular cycling position, because it’s more aerodynamic, but it wasn’t making enough of a difference.

Time was running out. It was planned that I’d do a practice day, then go for the record over two consecutive days on Brayford Pool in the centre of Lincoln, but another spanner was thrown in the works, making me think that perhaps the whole thing was doomed. Brayford Pool was choked with thick weed that would wrap around the hydrofoils and the water propeller.

Both boats came, and Ron looked like he’d got the hump when the plan B boat turned up, so we prettied it up to say it was single hull versus twin hull and water prop versus air prop. And it was – there was no denying it. The Lincoln team’s Ekranoplan idea never happened. They ran out of time to get it sorted.

We had nothing to lose so I gave it a go, attempting two runs with the Lincoln boat, but it went terrible, with loads of weed getting wrapped around the hydrofoils. Mike said the hydrofoils were so sensitive that one strand of weed could stop them working, and he didn’t even bother unloading his plan B boat.

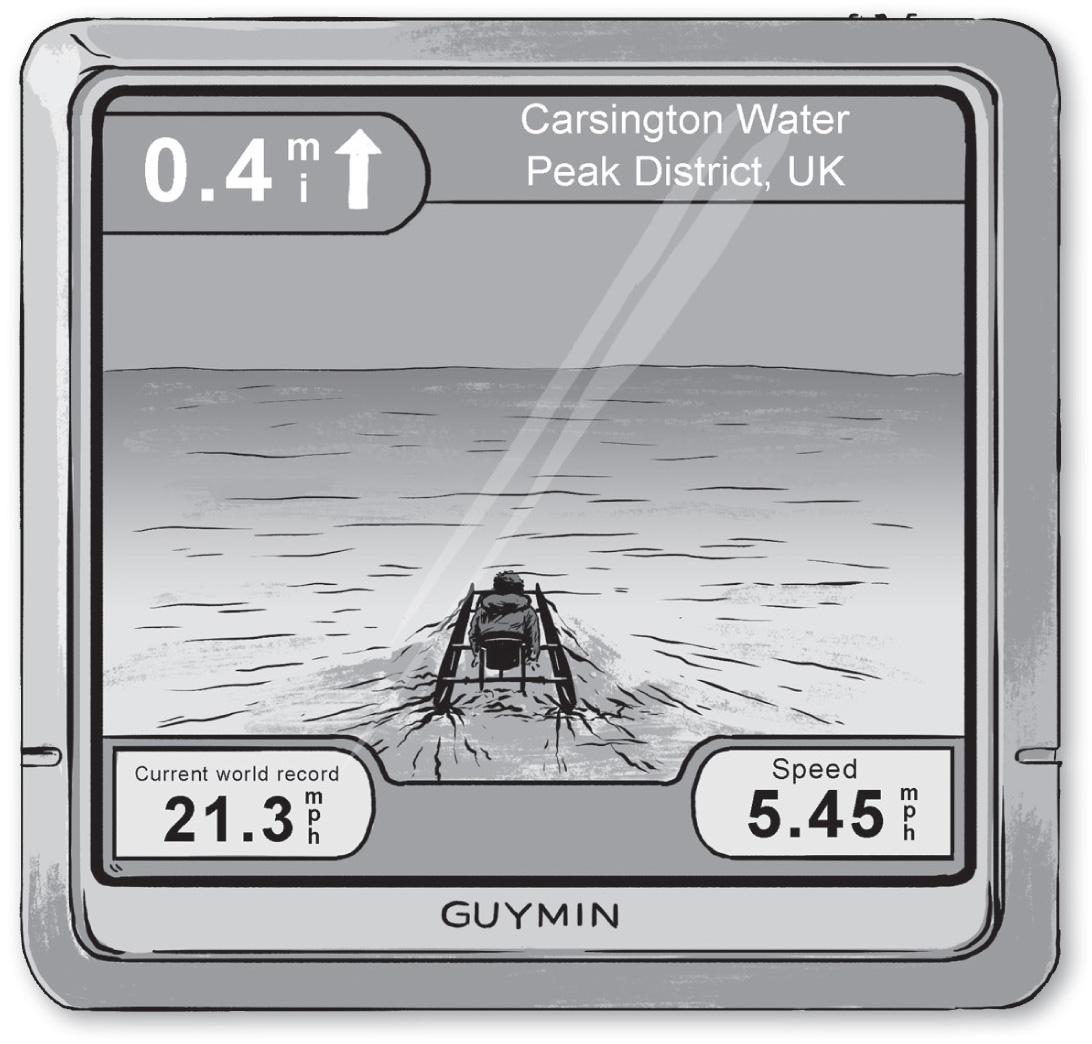

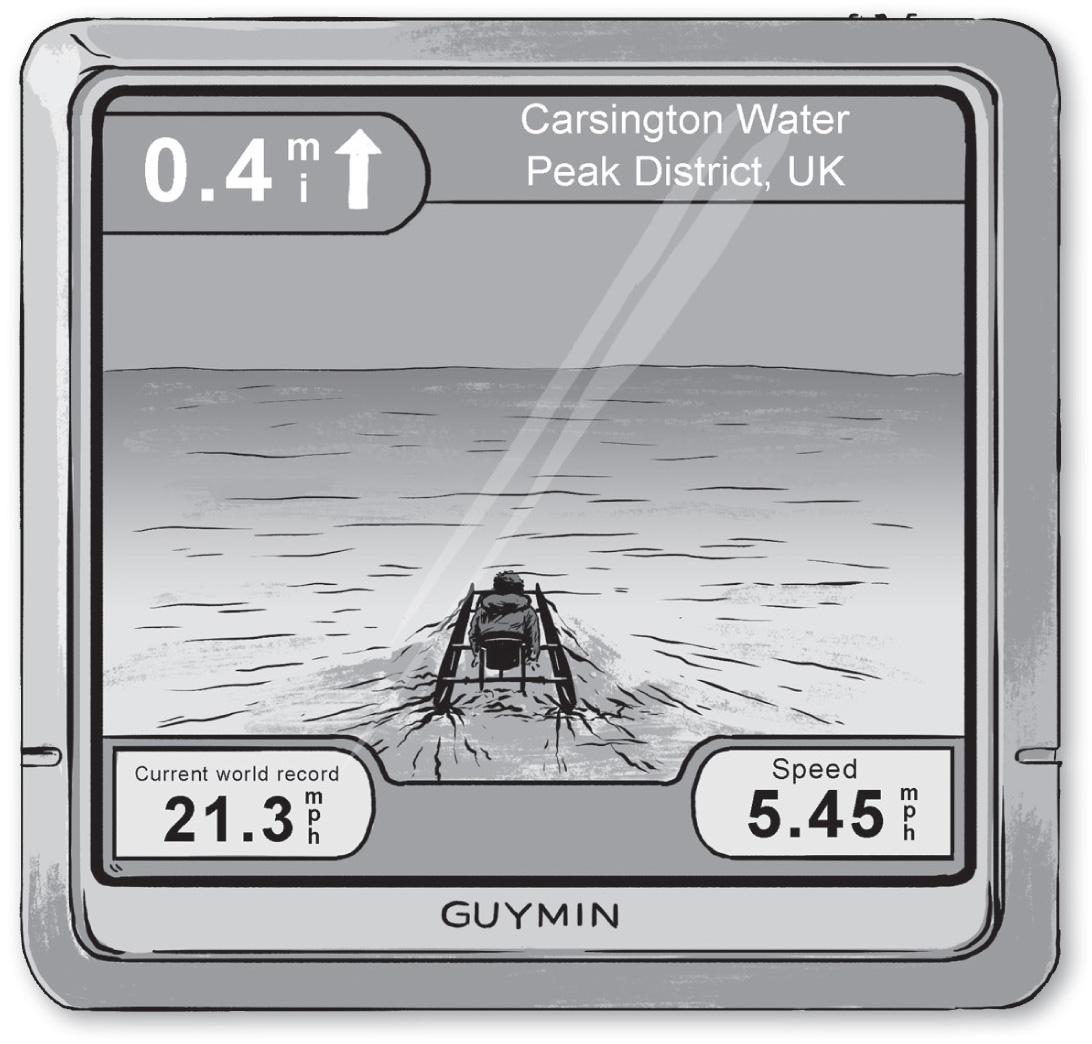

I did the two runs and it was back in the van and time to work out a plan. We found some clean water in a place called Carsington Water, near Derby, and headed there the next day with both boats.

We knew the Lincoln boat wasn’t going to bother the record, but I gave it another go. In that boat the harder I pedalled the harder it seemed to get. The Carlos Fandango asymmetric prop was so hard to turn, and it was jarring me every time I turned the cranks. I could only get a cadence of 60, when I really needed twice that. It was knackering. I was the fittest I’d ever been, coming off the back of the Tour Divide, but this required a different kind of pedalling. It was cough-your-lungs-up-for-a-couple-of-minutes effort.

Then I had a go with plan B, and nothing broke or gave any bother, but it was slow.

Neither of them got up on their hydrofoils. The MIT boat, the Decavitator, used a ladder system of hydrofoils and it obviously worked. The fastest I went was 5.45 mph, about a quarter of what I needed to match the record. I don’t even think Chris Hoy would be able to go four times as quick as me. A few people have tried to break Drela’s record since 1991, and it still stands.

The effort, both plans A and B, was a failure, but it showed that the records we attempt and usually break during the filming of Speed are not easy, and failing every now and then never hurt anyone. With three or four other record attempts coming up before the end of the year, I was hoping that I wasn’t going to make a habit of failing, though.