ATTEMPTING TO BREAK the outright motorcycle land speed record had been on the cards since I flew out to see Matt Markstaller in April 2015. That one-night trip, to Portland, Oregon, had been sold to me as making sure I could fit in the Triumph streamliner, because it was built with someone six inches shorter than me in mind. Markstaller is the hot rod builder and truck research and development engineer who had been paid by Triumph to build a motorcycle capable of breaking the land speed record, which at the time was 376.363 mph. I now realise that the trip was more of a job interview, with Matt making sure he wanted to work with me.

I must have said the right things, because the first record attempt was set to be in August 2015, but, as you already know, I broke my back, and Bonneville was flooded anyway. The Bonneville Salt Flats in Utah were formed when a prehistoric salt lake, 1,000-foot deep in places, dried up over hundreds of thousands of years, leaving all the salt and minerals that were suspended in the water to self-level and form a flat surface. People have raced cars on it since 1914, with regular annual speed meetings held there since the end of the Second World War. Now, weather permitting, there are three or four speed trial events, for cars and motorbikes, held there every year, and other private tests and record attempts on top of that.

The majority of the outright land speed records of all time have been set at Bonneville, but the car record is now so high, at 760.343 mph, that Bonneville isn’t big enough for them to get up to speed and slow down, so they look for other deserts. The folk behind the British Bloodhound SSC, which has a target speed of 1,000 mph, have prepared their own track in South Africa. Hundreds of racers still bring their hot rods and streamliners to see what they can do, with no dream or possibility of setting the outright car record. They’re looking for class records, personal bests or to break their own limits.

If the salt is in good condition Bonneville is just about long enough for motorcycles to reach 400 mph, though nobody has yet. Every outright motorcycle land speed record since 1956 has been set in Utah. Obviously, it would be good if it was longer, because it would be less important to accelerate smoothly up to top speed and you wouldn’t have to worry too much about losing traction as you got up to it. If you had longer to accelerate you’d also need less power, so there’d be less strain on the machine, but it’s a vicious circle. If people had a longer track, they’d still use more power and aim to go 450, not 400. We always want more power.

A year to the week after the Ulster crash I was on a flight from London to Salt Lake City, Utah, with my big sister Sally, some folk from Triumph’s Leicestershire headquarters and the regular North One TV lot for a week of testing in the streamliner.

After a two-hour drive from the airport, we reached the hotel in Wendover, the nearest town to the salt flats, late on Wednesday. The streamliner wasn’t due to arrive from Portland until the next day, but I’d been told that another team aiming to break the motorcycle land speed record was testing on the salt, and I was dead keen to have a mooch around. I wanted to find out as much as I could about the job, so early the next morning we drove out mob-handed to see what was occurring. Looking at how another team and rider were set up was an opportunity too good to miss.

Ten miles from Wendover, off Interstate 80, there’s a turn-off that leads to the salt flats. The tarmac ends, and there are two signs telling you, if you needed telling, that you’re on Bonneville Salt Flats. The salt stretches as far as the eye can see, to mountains over 20 miles away. The land is public, so people can drive on to it, but there are traffic cones set out and folk parked to discourage people from driving out when racers are testing.

Four or five miles on to the salt we found the BUB team and its owner, Denis Manning. Manning has been involved with motorcycle record breakers since 1970, when the Harley-Davidson streamliner he had summat to do with set a record speed of 254.84 mph with the late American road racer Cal Rayborn in control. Manning used to own a company making motorcycle exhausts called BUB, and his bike, the BUB Seven Streamliner, was the world’s fastest motorcycle in 2006 and 2009.

I looked into a bit of history of motorcycle speed attempts. The official motorbike record broke the 300 mph barrier in 1975, when Don Vesco went 302.9, in Silver Bird, a twin-engined streamliner using Yamaha TZ700 two-stroke road-racing engines. Vesco broke his own record in 1978, with Lightning Bolt, a new streamliner with two turbocharged Kawasaki Z1000 engines, going 318.6. That record stood for 12 years until Dave Campos, in a twin-engined Harley-Davidson, went 322.2 mph. It was another 16 years before Rocky Robinson in the turbocharged twin Suzuki Hayabusa-powered Ack Attack went quicker, raising the speed by 20 mph. Just two days later Chris Carr in the BUB broke it again, and became the first man to do an average of over 350 mph in a motorcycle streamliner. Over the next four years the record went back and forth between the BUB and Ack Attack, with Rocky Robinson and the Ack Attack coming out on top in September 2010, with their 376 mph two-way average, but their top recorded speed was 394 mph.

Setting a land speed record is not just a case of hitting the fastest ever speed for a second. The machine must do two passes through a timed mile, one in each direction to account for tailwinds or gradients. And the second run must start within two hours of the first one. A one-way speed is determined as the average speed through the mile, and bikes are often going faster at the end of the timed mile than when starting it. The two speeds are added together and divided by two to give the record speed.

The BUB team were dead friendly. Manning and his son worked together with a crew of six or seven trusted old hands. It was obvious they’d been at it for years, and they were happy for me to ask questions, though I’d been warned to take everything Manning told me with a pinch of salt (there was no shortage of that). I’m not stupid, though. I know enough to realise when someone’s bullshitting, and I didn’t think they were. Or not too much, anyway.

Manning explained that their bike had been in development for 16 years and had a purpose-built V4 engine in it. They cast the casings, the full lot. I was impressed. It got me half-thinking that just bolting two motorbike engines in a streamliner was taking the easy route, but other than the BUB bike, every record since 1966 has been held by a streamliner powered by two modified production-bike engines. The bike that currently holds the record, Ack Attack, has two Suzuki Hayabusa engines in it.

The other thing about the BUB is that it is the only streamliner, except for the Triumph, that has a monocoque chassis. By that, I mean the body of the machine is what gives it its strength. All the other streamliners have a steel frame or skeleton that the bodywork is bolted to. Manning and Markstaller agree that the monocoque is the safest construction, but one of the main organisations that run speed trials on Bonneville, the Southern California Timing Association, don’t allow monocoque bikes to run at their meetings. They’re more set up for cars than bikes, so Manning started his own BUB Speed Trials, purely for motorcycles, and the meeting still runs now, but with his ex-daughter-in-law running it. The reason fans of monocoque designs are convinced they’re better than regular space frames with bodywork attached is because they believe a monocoque keeps its shape better in a violent crash and stays sliding on its side, while a space frame streamliner can lose bodywork more easily in an impact and develop a sharp edge that can dig into salt and flip it into the air.

The week before I left for Utah, another racer aiming to break the land speed record had died testing at Bonneville. Sam Wheeler was 72, and he had been racing on the salt flats since 1963. He’d gone over 200 mph as early as 1970, and his top speed was 355 mph. He built his own streamliners, and the current one was powered by a single Suzuki Hayabusa Turbo.

I’d read that, in 2006, he’d crashed at over 350 mph and survived. This time eyewitnesses reckoned Wheeler was doing closer to 200 mph when the 500bhp streamliner started fishtailing. I was told it slid for a while, which is the best you can hope for when a streamliner crashes, but then flew up in the air and came down hard, and then it did the same again. The rider was alive when he left Bonneville, but died soon after. The news was horrible, but it had also got me even more interested. Before I heard this I’d thought breaking a land speed record was just a case of pointing the right machine at the horizon and getting on the throttle. I didn’t think it was much of a challenge for the rider, but now I knew that it was this dangerous, it was a different kettle of fish.

The BUB team had a new rider too. Both of BUB’s speed records had been set by Chris Carr, the dirt-track legend and multiple champion. Now they had Valerie Thompson, a 49-year-old drag racer and Bonneville regular, from Las Vegas. Lovely woman, and, like all the BUB team, dead friendly and open. This four- or five-day test was her first time getting to grips with the streamliner, and she’d spent the time being towed behind a truck at 50 mph to get used to balancing the bike. These streamliners are heavy, and you’re strapped into a seat so you don’t have the same influence over the balance of the bike – you can’t just put your foot down to stop yourself falling over. Valerie has been 217 mph on a BMW S1000RR superbike, so she wasn’t a messer, but the streamliner was something else. She had it on its side a couple of times during her test, but no one was batting an eyelid. They seemed to expect a couple of gentle crashes.

The BUB lot were switched-on blokes. Their streamliner looked a bit Heath Robinson, but bloody impressive to say it was only a shed effort. In the 16 years they’d been working on it, BUB and their sponsors had obviously spent some money, but now it looked a bit rough around the edges. It has done impressive speeds, having gone over 140 mph faster than the Triumph streamliner had up to that point. Talking to them while we were waiting for the Triumph to turn up put me on the back foot a bit. No one was slagging Matt Markstaller off, but the 16 years of development and one-off engine stuck in my mind.

During that first morning on the salt flats I also met Mike Cook, who felt like the father of Bonneville. If you want to do any private testing or book the track to attempt a record, you see him. He’s a car racer whose dad was a drag racer, and his son is a drag racer and Bonneville racer, too. He’s in his sixties, and small and weathered from day after day of being out in the baking sun. He knew everyone, had driven his own Ford Thunderbird at over 300 mph, and he had recently restored a car called Goldenrod, which was the world’s fastest wheel-driven, piston-powered car, just as the era of turbine and jet cars started raising the speeds and claiming the outright land speed records. In 1965, Goldenrod took the record from Donald Campbell’s Bluebird, so to be trusted with restoring that car proves how respected he is. I talked to Mike Cook on and off all week. He put my mind at ease over a load of stuff. We had a good few yarns, both out on the salt and in a cool little bar called Carmen’s Black and White. He was dead friendly, just a brilliant bloke. His crew of helpers drive up and down in trucks, pulling heavy graders made from steel beams welded together to smooth the salt as best they can, and he put Triumph in touch with everyone from the fire and ambulance folk to the official timers that we’d need to run out there.

The BUB lot liked to talk, and I was happy to listen. I got the feeling they’d told the stories a hundred times before, but it was all new to me. Denis Manning, who named the bike after his company, BUB – Big Ugly Bastard – told me he got the shape of his bike after watching salmon swim up a river, and it sounded like a good story. When Matt Markstaller arrived later in the day he’d also heard the same salmon yarn, but he pulled a face that gave me the impression he didn’t believe it. Where BUB were clever engineers and good old boys, Matt was different. When it came to deciding the shape for his streamliner he researched the most aerodynamic shapes American engineers had ever come up with. The shape he chose in the end was a plane fuselage designed by NACA, the National Advisory Committee for Aeronautics, the forerunner to NASA. He wasn’t guessing or spinning a yarn about fish – he was dealing with scientifically proven hard facts.

Markstaller brought a big team of helpers to keep the streamliner fettled, but there were a few main men. Most important was Matt himself, who designed and oversaw the building of the machine. Also there was Ed from Carpenter Racing, in New Jersey, who built the engines. This was the first time I’d met Ed, and I hit it off with him straight away. We were both into Snap-on tools, and I could tell from the way he wields a spanner that he knows what he’s on about. He has a certain way of building engines, and we spoke for hours about compression ratios, intake ports and lock-up clutches.

James was the brilliant electronics man. You’d think he’d come out of MIT or something, and maybe he has. A very clever man who would answer my questions about the rate of acceleration and the length of track by telling me I needed to accelerate at 0.2 g to reach 400 mph in five miles, but to achieve that we had to have an aerodynamic drag coefficient of friction of 0.1 – or summat like that. He’s not playing at it.

The other main man was Dave – Crazy Dave. He was in his seventies, the oldest man on the team, and was an experienced drag racer, expert welder and machinist with long white hair and an eye patch who had machined and welded a load of stuff for Matt. I looked at some of the stuff he’d made on old-fashioned, manual milling machines and couldn’t work out how he’d done it without the help of a modern CNC machine.

The other team members were friends or Markstaller family members, and had jobs from checking the coolant levels in the belly tanks to filling the fuel tank, removing the panels to get to the engine, cleaning the screen, checking tyre pressures and tyre condition before every run, driving the tow truck … There were about 50 items to check before every run. Ed would only get his hands on it if something wasn’t going quite right. He’d done all his hard work back in New Jersey, when he’d tuned and built the engines.

The Triumph lot had allowed BUB to continue using the track for an extra day after they’d lost one because of rain. It was no skin off our nose, because our bike wasn’t arriving until midday Thursday at the earliest. In the end, it didn’t arrive till gone three in the afternoon.

I was itching to get out in it as soon as I could, and Matt said I could have my first go at getting to grips with it that day. The streamliner had been transported in a trailer and was suspended under a heavy steel cradle, which held it about 3 feet off the floor so it was easier to work on. The team checked everything over, then, late that afternoon, I got the nod to get in my kit, ready for the first ride.

I would be towed behind a big American GMC Yukon, so the streamliner was fitted with big stabilisers, bolted on halfway down its length, to do the same job as those on a kid’s first bike. They’d be left on until I proved I had the hang of keeping it upright. The Triumph also had little retractable alloy legs, less than a foot long, that popped in and out of the bike’s belly when I pressed a button. When the stabilisers were eventually taken off, these would keep the bike from falling over when I came to a stop.

I climbed into the bike’s cockpit, and it was snug. I’d lost weight since I first tested it, and that helped, but there was still a knack of getting in and out, because it was so bloody tight. To get in, I first had to brush all the salt off the sole of my right shoe, stand in the bike, then brush the other off. When I was standing in the gap in front of the seat, I lowered myself down and slid one leg, then the other, under the dashboard, pushed my backside into the back of the seat and tucked my head under the carbon-fibre loop that was designed to protect me if it ever started barrel-rolling. The bike was fitted with five-point harnesses. Wide, heavy-duty seat straps went over each shoulder, and two around the waist, and they all met at one buckle over my belly. I also had wrist straps that fastened to the harness, so if I crashed my arms would stay in the cockpit instead of flailing outside and getting crushed by the rolling bike, which weighs close to a ton.

I wore my regular AGV helmet for the early practice runs, even though it wasn’t approved for record attempts. I wanted to wear something I was comfy in and wouldn’t distract me, because everything else was so unfamiliar. The team said they’d leave the canopy lid off for the first towing runs. I wasn’t going to be moving quick enough to need it, and it was a bit easier to talk and make myself understood without it. The canopy was a curved screen in a carbon-fibre frame with a trick release mechanism. It looked like it was straight off a jet fighter. It wasn’t hinged like a door or a hatch – it had to be lifted into place and clipped down. If I ever needed to get out in a hurry, I’d just release the catch and push it off. A long climbing rope was tied to the stabiliser legs and attached to the back of the Yukon. The car set off very gently and slowly. I had my hands on the controls and was getting the feel for how much input I had to give to steer this nearly 26-foot-long bike. Our pits were set up at the one-mile mark, with the course being seven miles of usable salt, 120 feet wide, and we headed east down the track.

By the time we’d got a few miles under our wheels I had the thing balanced at 35 mph. Matt was in the back of the 4x4, with its hatchback open, and Nat the cameraman was set up next to him. Matt must have been surprised I’d got the hang of it so quickly, because he was saying, ‘Well, will you look at that?’

I’d heard that Jason DiSalvo, the Triumph team’s only previous rider, took a week to get up off the stabilisers and balancing while being towed, so I didn’t know how hard it was going to be. But I was up and balancing on the very first run. I had to give constant little adjustments to the steering, but I got the hang of it, and I’m no Danny MacAskill, so I don’t know why anyone else would have so much bother.

Even though Triumph had allowed the BUB team to keep practising on the salt for free, and were dead friendly earlier in the day, someone had squealed to Mike Cook about us doing this little 50 mph towing run without the ambulance being on the track. Perhaps they were trying to play mind games early on. It seemed a bit daft.

The original plan was that we’d be out on the salt at 6.30am and off by midday, because the wind was usually calmest early in the morning. There are rules that don’t allow streamliners to run with side wind of more than 4 mph, so there can be a lot of sitting around waiting for the weather. Mike Cook also explained that the desert sun brings moisture to the surface of the salt as the day goes on, so it’s the opposite of what you’d expect. You’d think the track would be damp overnight and dry out during the day, but it doesn’t. It was all new to me, and I just wanted to be out there every minute we could.

I’d get up at five and walk over the road to the petrol station to have coffee and porridge, because it was cheaper than the hotel. I’d meet the TV lot in the car park at quarter-past six and drive out to the salt in their rented Transit van. Triumph had brought three camper vans, one for Triumph and their photographers to work out of, one for the TV lot and one for me and Matt to use, but I didn’t like the idea of having one. I don’t want to be treated differently to the rest of the team. I try to explain to them that I’m only a wanker, nowt special, and I don’t want or need special treatment. There was a medical helicopter booked while we were running. It was there from seven in the morning, and the crew ended up hanging around in the motorhome that had been brought for me, so it wasn’t going to waste. I will admit it was good for having a wee in without having to drive to the Honey Buckets, the portable toilets at mile zero. We made the rule to drive down to those for a number two, and we also knew that if someone drove off in a car on their own, they were going on a Honey Bucket run.

Day two, Friday, the first proper day, started with more tow runs. We’d leave the pit, at mile one, and head to the seven-mile marker, then turn around and come back. Everyone was dead pleased with the progress. We hadn’t been over 60 mph, but people kept saying it had taken DiSalvo more than a week to get to this stage. By early afternoon we moved on to braking practice. People reckon the braking part is the most dangerous part of a record run, but this was just slow-speed stuff. We did over 20 practices, being towed up to speed then braking down to a standstill. The brake was a carbon-carbon set-up, which means carbon-fibre brake pads on a carbon-fibre disc. It can deal with a lot more heat than a conventional steel or iron disc, and the hotter it gets the more it grips. This type is used in F1 and MotoGP, but Matt got the streamliner’s brakes from the company that made the brakes for the space shuttle. All the practices boiled the brake fluid and the brakes eventually faded, nearly making me crash into the back of the tow car. It wouldn’t be a problem if I ever had to brake from more than 400 mph, because there would be more air passing around it – and I’ll also have parachutes to do a lot of the braking.

The waiting around meant I could spend more time looking at the bike and quizzing the people who built it. I’d seen the streamliner before, and knew how well made it was. No expense was spared. It looked just the same as when I’d seen it last time, all nice bits and bobs, any bare metal anodised, and it was well beyond anything someone would build in their shed. The front end had hub-centre steering, like a Bimota Tesi or Vyrus, not regular forks. Matt chose this design to keep the front end lower. The front wheel bearings were $8,000 each, and there were two of them. Matt ordered them from Germany. The special grease for the bearings was $200, not £10 from Cromwell’s. Even Matt said he wouldn’t normally go to these lengths, but Triumph wanted the best.

I found out a lot more about the engines. They were modified Triumph Rocket III motors. They’re the biggest production motorcycle engine, at 2294 cc, but while land speed record bikes can have more than one engine, the maximum cylinder capacity is 3000 cc, so two standard Rocket III engines would be too big. When I wrote When You Dead, You Dead I got a couple of details about the engine wrong. I thought Carpenter Racing had reduced the size of the bore to reduce capacity, but they’d kept the stock piston size and reduced the stroke with a new crank to get each engine’s cylinder capacity down to 1480 cc. The crank had titanium conrods fitted and low compression pistons. Carpenter had designed a new cam too, but the valves were standard.

Both engines were fitted with their own turbos, but they were nothing fancy and had internal wastegates. The engine was fed by bigger flow fuel injectors. There wasn’t room for an intercooler, but the bike would run on methanol, not petrol, and that runs cooler.

There were still a lot of original Triumph parts left. The crank cases, gearbox and most of the clutch were all standard, but Carpenter had made a centrifugal pressure plate for the clutch that made it like an automatic. There was no clutch lever or pedal.

At the end of day two, half-three on a Friday afternoon, the weather looked good enough for my first power run, but there was a problem with a wheel speed sensor, which was affecting the traction control. I didn’t think it would matter for this first slow run, but then Nik Ellwood from Triumph said the helicopter was only booked till four, so there was no point in rushing and running without the sensor. I wanted to get the run in and told him I’d sign anything to say I knew the risks and was happy to run without the helicopter, but contracts had been organised between Spellman and Triumph, and Nik wouldn’t let me. When people started talking about contracts I felt I had to explain to the team that I wasn’t being paid by Triumph or any of their sponsors to be there.

Nik was the one who’d suggested I should be the man to ride the thing, so I was dead grateful for that. He had a tough job, being the middle man between the team, the factory, sponsors, journalists, photographers and me. I wouldn’t want to do it.

The next morning, I was towed up to the seven-mile point for the first test run. Following me was Matt and his eldest son, Ian, in a rental Camaro muscle car; the film crew come in a 4x4, Mike Cook in his massive pick-up truck, Eric the Öhlins suspension man in his car, plus Ed and James the electronics man in another rental car.

The streamliner had a massive turning circle, and we’d made the mistake on the very first towing run of going off the track to turn it around behind the 4x4, and it had got totally caked in the softer salt where it hadn’t been graded by Mike Cook’s track workers. The front wheel was now pushed on to a metal skid with a long rope attached to it, and six people pulled and pushed the bike around 180 degrees, to point back to where I’d come from, while I had my foot on the brake.

This was it, the first run. I was told to go no more than 80 mph, and I had the stabilisers fitted. Now that I was more used to things the canopy was fastened down, like it would be for every future run, and I got ready to start the engines. The starting procedure is this: Matt holds one finger up and I start engine number one, then he gives me the thumbs up before putting up two fingers, for me to start engine number two. With both engines running and everything looking and sounding good, he puts his thumb up and walks away to his car. I have to leave it ten seconds before I set off.

The bike is already in gear when I start the engines, and it has that automatic clutch, so I just twist the throttle. I went 50 feet, if that, before the bike lost drive. The cars that were following me all stopped and people ran out to come and take the canopy off. I explained that it just lost power, and the crew set about taking off the long engine cover panels to see what had happened. They worked out that there was no drive from the engine to the back wheel. There were a lot of things that could have been causing it. The drive train of the Triumph streamliner was a trick set-up. The two Triumph Rocket III motors drive through their standard five-speed gearboxes, but the two gearboxes are linked with a shaft that drives another short shaft through a Porsche CV joint. The output from there acts like a shaft drive on a regular Triumph Rocket III leading to a rear hub. Instead of the Triumph hub, the streamliner has a bevel gear set-up from a racing speedboat. Matt didn’t know what was broken – all we knew was that there was no drive between the engines and the rear wheel. We didn’t want to risk towing the bike the six miles back to the pits in case something came loose, started flailing around and damaged another part of the bike, so we had to wait while the 4x4 drove back, bolted the towing bracket to the frame that picks the bike off the floor, brought it up to the bike, raised the bike then towed it back to mile one.

It was heading towards Saturday dinnertime, and different causes were being guessed at. There was talk of best-case scenarios. Some problems could be fixed relatively easily, others might bugger us up for days. At the very best, we’d lost the day. There were only three to go, and who knew what the weather was going to do?

A good hour after getting back to the pits, we found out that the driveshaft had snapped, where a spline has been welded to a shortened shaft. Crazy Dave knew someone in Salt Lake City, 120 miles away, who could weld it. We – me, Matt and Dave – got in the rental Charger and set off. Dave’s mate was a bloody brilliant welder. He told Matt that the shaft wasn’t the steel he was told it was.

It was early evening when we got back to Wendover and I walked down to Carmen’s Black and White Bar, the place I’d been told about. It’s a wooden building, definitely nothing fancy. It looks like a big shed that’s been painted white and it has no windows. You’d never find it if you weren’t looking for it, as it’s down a backstreet with mobile homes parked around it. It doesn’t look promising, but you walk in and see the walls covered with posters and photos of Bonneville racers. It’s run by Carmen, a women in her sixties, who is the only person who works there. Sally was there with Sideburn editor Gary Inman, who’d also travelled out to see what was going on. I had a bottle of beer as I looked at the photos, then Mike Cook came in. Carmen made me a cup of tea and I talked to Mike for an hour. He’d never raced a bike, but I could ask him loads of questions about the salt and how machines behaved out on it. He told me that if I ran off the track I didn’t have to panic, I just had to steer back on. I walked back to the hotel with Sal and Gary. Sal wanted something to eat so we stopped at the Subway, next to the petrol station where I had breakfast, but I still couldn’t bring myself to eat there after having so many on the Tour Divide.

The next morning we were out at the pits at 6.30 as usual. The bike was nearly back together, and I thought we’d be ready to go as soon as the helicopter landed, but we hardly ever were. If Mark McCarville, the foreman from the TAS team, were here the team would work as long as it took after we finished riding to be ready to go the next morning, but this lot seemed to leave a load of jobs for the next morning. I couldn’t understand it, but I kept my nose out. I’m sure there was a good reason.

I wasn’t being impatient, but I had a lot to learn about the land speed job, and the best way to learn is by riding the thing – seat time, as the Americans put it. Before too long everything was bolted together and ready to tow up again. I didn’t have any shoes on, because room was so tight in the nose that I was having a bit of a struggle to comfortably get my foot on the brake pedal. I wanted to ride in just my socks, but Matt made me wear driving boots.

At the far end of the track the stabilisers were bolted back on. They were adjusted so the stabilisers’ wheels were off the floor, like they were on the towing runs. They were there just to catch me if I tipped over. First gear needed to be engaged by hand, so the side panel was removed, then fitted back in place with about 20 screws. I started the engines, got the thumbs up and set off.

Like anything on two wheels, the streamliner is at its least stable at slow speeds, so I’m on the little wheels of the retractable landing gear legs till I get up to 30 mph, then I’m balanced.

Unsurprisingly, the controls are different to a regular bike. I have two handles or joysticks, I suppose, bolted to either side of the cockpit, next to my thighs. They’re aeroplane grips and just move forwards and backwards, not side to side. I twist the throttle, as normal, but it’s vertical, not horizontal. The brake is operated by a foot pedal – there is no hand lever. On the grips I have two buttons to change gear, one each for up and down. I have two more buttons, up and down for landing gear.

I have a MoTeC dash, with loads of information on it, but I’m only looking at speed. If anything happens to oil pressure, oil temperature or water temperature, it’ll flash warning lights at me, so I don’t have to be reading the numbers.

I accelerated steadily away, short shifting before the turbo boost came in. Behind me, out of my line of sight, all the cars were following. I had a radio earpiece and I could just about hear, and talk to, Matt.

From mile seven to mile five and a half the streamliner’s wheels were following ruts, like a car follows truck’s ruts on a worn-out motorway, but I could control it. I also had double-vision when the canopy was fitted. I was seeing two of every mile marker, so I closed one eye.

The Triumph felt like Nige – pulling on the lead so hard it’s strangling itself, as all it wants to do is run faster. The first run went without a bother. It was so easy it was a bit boring. I felt confident to go faster, but I was there to jump through all the hoops that the Bonneville authorities put in front of me, and I had to prove I could safely handle the bike at certain speeds before moving to the next speed, so I kept it close to 80. I was doing 3,200 rpm in third gear.

James, the electronics man, confirmed that I actually touched 92 mph, and I wanted to go again, but the streamliner needed checking. The side panels were taken off and the belly tanks where the radiators were mounted in tanks of water were removed to have their temperatures checked.

Mike Cook, who followed behind on every run I did in the practice week, told the team that he’d never seen anyone get to grips with balancing as quickly as I did, but 90 mph is not 400 mph, so I wasn’t getting too excited. Then the wind got up. Mike won’t let any record bikes run on his track in more than a 4 mph crosswind, and this was all of 10 mph, so the rest of the day was a write-off. We were making progress, but I just wanted to keep riding the thing. I did a bit of filming with the TV lot then got back to the hotel to work on this book.

I was in the pits raring to go at 6.30 on Monday morning. We only had two more days of testing and I hadn’t even been over 100 mph yet. I’d been faster than that pedalling a pushbike along a Welsh beach. Then, when I thought we were finally going to do the run, I was told I would have to practise getting in and out of the cockpit, so I knew what to do in an emergency. Why didn’t we practise this the day before when the wind was too high to do anything else?

I did need the practice emergency exit, though. My first attempt wasn’t very good – I was rushing and got my legs stuck. It made me remember that I had to get out from under the dashboard one leg at a time. Everyone was happy with my next attempt, so the bike, still suspended above the salt in its frame, could be pushed on to the track, lowered, tied to the truck and pulled to mile seven.

This was supposed to be my 120 mph run, but Matt said I could take it to 150 and no one would complain. This would be my second power run, and the first without the stabilisers. I started the engines, moved 20 feet and the engines stalled. Everyone ran out to the bike and took the panels off while I stayed in the cockpit, helmet on, canopy off. It wasn’t a quick fix so I eventually climbed out. One motor started but the other sounded like it had a flat battery. James and Ed thought it might be mechanical. I didn’t think it was, because it petered out like it had run out of petrol. When the laptop was plugged in it told us that a cam sensor wasn’t reading, but we didn’t know if that was because something had broken and damaged it, or not.

We towed the bike back to base and the team started investigating. I wasn’t getting frustrated – I just wondered what it was. It turned out just to be a cam sensor problem, and in an hour the bike was running properly, with the same sensor. I was surprised they didn’t swap it while they had the chance, but the bike seemed to be running alright. Luckily, the weather hadn’t changed for the worse, so we headed back to mile seven. From there it was impossible to see the pits, and if anyone needed anything it was a 12-mile round trip to fetch it.

This time everything went according to plan. I was riding with one eye, because of the double vision. I had been swapping eyes during the practice towing runs, but it took too long for the other eye to focus, so I just kept one closed.

When I set off it felt like the wind got me and I couldn’t get it balanced, so I left the landing gear legs down longer than normal till I got it right. Mark started shouting down the radio, but I couldn’t hear what he was saying, so I stopped. He was telling me the legs weren’t up, but I knew that. Just leave me to it.

After going through the starting procedure again I set off, and this time I got settled quickly. I looked at the speedo expecting to see 60 and I was already doing 120 mph, the maximum I was supposed to do, but Matt had already said I could do 150. Next thing I knew I was doing 180, 190 – it came so easy – so I thought, Let’s see what it’ll do. There was no sensation of speed, which was why it could feel boring. The team had set a rev limit, electronically, which stopped me revving the bike as hard as I wanted. This was the first time I tested the parachutes. I released them in the order Matt told me: right hand release first, then left. This deploys the big one first.

The convoy of cars caught up. James plugged in the laptop and confirmed the speed, 219 mph. It felt like we were getting somewhere now. We weren’t doing two-way runs or speeds over a timed mile yet, just recording peak speeds, and at 219 I felt I could have had one hand off the controls, smoking a cigarette. Everyone was keen to get the bike ready for another run, and everything was checked within an hour.

It wasn’t long before I was towed out to the seven-mile marker again, and the rev limit had been increased a bit. Again, everything went smoothly with the start-up procedure and launching off, but it didn’t stay that way for long. At close to 200 mph the bike got out of shape, and the whole thing was fishtailing. It was moving so much I was nearly looking out the side of window. I thought it was going on its side. I was in a hell of a wobble, but the more I fought it, the calmer it got. It’s the opposite on a TT bike – if you hang too tightly on to one of them when it’s tankslapping, it sends the movement to you, and it gets worse and chucks you off. In the streamliner I locked my knees under my arms, which calmed it down, and it came in line again. I lost about 10 mph while I was fighting it, then I gathered my thoughts and got back on the throttle to reach 256 mph. I had now gone faster than Jason DiSalvo had gone in the Triumph.

I was on the throttle non-stop for 20 seconds, but the engine was still hitting a limiter and not letting me go any faster. I rolled the throttle at mile three because I was bored of sitting at 256. Mike Cook had turned the big mile-marker numbers that line either side of the track around so I knew where I was. It’s deceiving how far the pit camp is away. I got to the two-mile marker, so one mile from the pits, before pulling the parachute. By now I’d been told to use the small one first, the opposite of what I was told at first. Then I got everything settled, going down a couple of gears, giving it a bit of brake, and then at 40 mph I pressed the button to get the landing-gear legs down.

The TV lot’s on-board cameras had caught the action, and you could see the horizon tipping from side to side as the streamliner fishtailed. The team looked at it and Matt didn’t know what was causing it, but I could see his gears turning as I was talking to him. He was coming up with different ideas, and I liked the way he was thinking.

He reckoned it could be the rear tyre. It had quite a square shape and he thought I might have rolled off the edge of it, and that put it in a weave. He asked the team to fit a bigger tail fin to help stability and called it a day.

The wobble didn’t make me want to stop riding it, but I planned to wear the OMP helmet with the HANS device now. HANS stands for Head and Neck Support. The helmet is tethered to a shoulder harness that limits how much the head can move forward or back in relation to the body, and should stop injuries from whiplash movements. A lot of car-racing series, including F1, have made them compulsory, and I was used to riding the thing by now, so I didn’t need the familiarity of the AGV any more. I wanted the added safety of a helmet with a HANS device, and bike helmets don’t have the screw holes to fit one to.

I headed back to the hotel to keep working on the book. I began to wonder how many boys had been killed doing the land speed job and, for the first time in my life, started seriously thinking about writing a will. If it does go on its side at 250 mph, what’s it going to do? It’s going to get messy. Matt said that the streamliner’s body had been built to withstand 50 g, but I haven’t. I wasn’t the only one who thought it might be dangerous. I heard that the insurance policy to cover me for the attempt cost over £60,000.

When it got wild, I realised how fast it was going. For each go on the flats, I was towed away from the pits and then I made the run back towards them, but after the wobble I got uncomfortable with the thought of heading back towards the pits. If I lost control, who was I going to plough into? I’d rather head towards Floating Mountain, in the east, so if I lost control I wouldn’t crash into anything. Matt wanted me to keep doing it how we had all week, running from the Floating Mountain end of the course, because he reckoned the salt was soft between miles one and two and it would affect acceleration. I couldn’t tell the difference between hard and soft salt when I was in the thing, but it tried to follow ruts, and if it did I had to go with it.

Tuesday started the same way as usual: cheap porridge in the Shell station and ten minutes’ drive out to the salt. The helicopter landed 100 metres from the pits at seven, while the team were doing their morning pre-ride checks. It was 9 August, and the last day of testing. We didn’t know if the taller tailfin was going to make any difference to stability, but there was only one way to find out.

The mood was different. Everything was a bit quieter after the previous day’s wobble. When I climbed into the cockpit to be towed out, Sal came up to me and said, ‘Go steady.’ I laughed and reminded her that I wasn’t here to go steady.

They towed me out to just beyond the seven-mile marker this time. It always felt bumpy and rough as hell when I was being towed out, but the faster the streamliner went, the smoother it became. The front end has three fancy, Superbike-spec Öhlins TTX shocks to damp it, and they seemed to work better at speed.

This was the 250 mph run, but, as usual, I wanted to go faster. The run was smoother than the previous day’s. The streamliner was still following ruts, but I could deal with it. I was always tweaking the steering, using the horizon as the guide, keeping that dead level. The machine wasn’t talking to me – I wasn’t getting any feedback. It was all visual. I changed gear when the light came on, and the traction control was looking after itself. It sounds easy, but it isn’t. Nothing went wrong, but it didn’t reach the speeds I wanted it to.

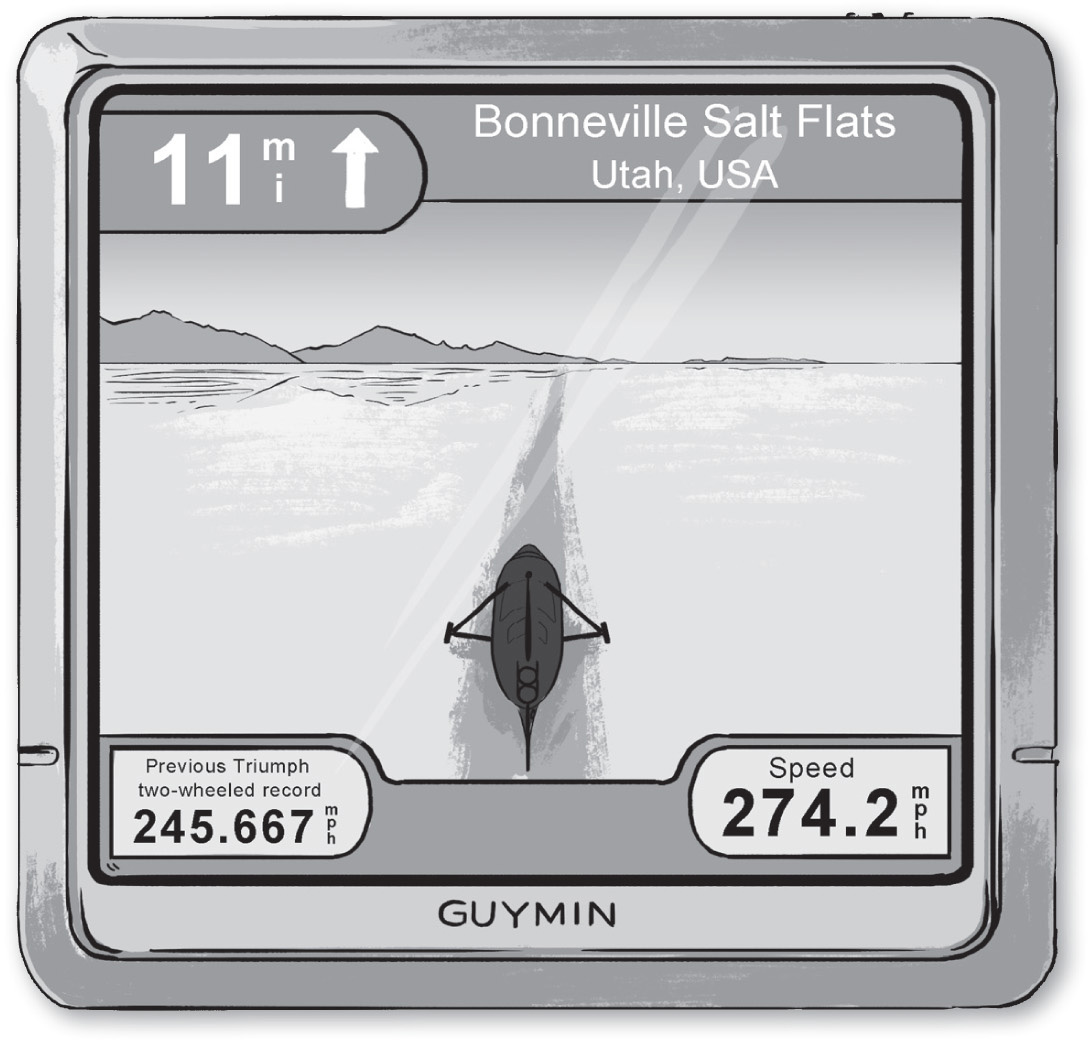

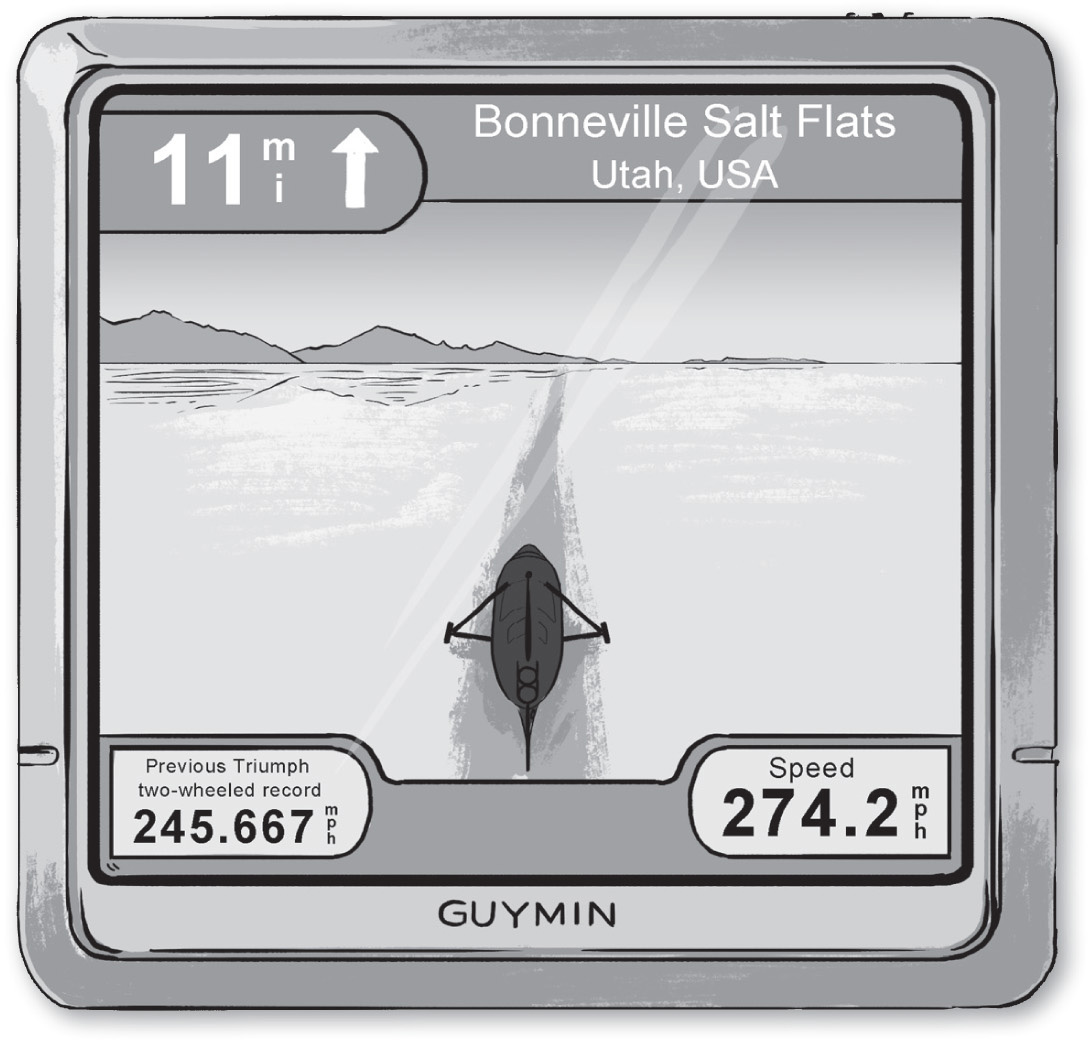

I pulled the parachute at two miles and coasted to a stop a couple of hundred metres from the pits. The recorded speed was 274.2 mph. Matt seemed pleased enough, and there were no big wobbles this time. Triumph were happy because it meant the new streamliner was their fastest ever, and had something to tell people. The top-speed record we broke was set in 1966, by Bob Leppan in Gyronaut X-1, with two air-cooled, bored-out 650 Meriden twins, so if we couldn’t go faster than that, with 50 years of technological advances, two turbos and twice the cylinder capacity behind us, there was something badly wrong. That’s why, for me at least, it was just a step to where we wanted to be and not much more. We want to break Ack Attack’s world land speed record, and that stands at a two-way average of 376.363 mph, over 100 mph faster than the Triumph streamliner has ever been. The team, and Triumph, want to be the first bike over 400 mph. I was happy enough. We’d moved in the right direction all week, and once we went over 230 mph it was all into the unknown for the team.

I did want another run, to try to go over 300 mph, but Nik from Triumph wasn’t keen and Matt agreed, explaining that there wasn’t a lot of point putting more miles on the streamliner because we wouldn’t learn much from going just 26 mph faster. The first thing I have to do at the record meeting, whenever that will be, is to do a 300 mph run in front of the FIM, the Fédération Internationale de Motocyclisme, to prove I can do it, but it would’ve been good for my own peace of mind to know I had done over 300 mph before we packed it in. Having said that, it was trick being out there, being involved with something with this much planning and effort behind it. I am honoured that Triumph chose me, but it’s not going to be plain sailing. Mark is concerned about the state of the salt. He made it clear that everything has to be perfect to have any chance of breaking the record. He explained that if I get wheelspin during acceleration on a record run I should just park it, wait for the tow truck, go back to the beginning and try again. If it’s not a perfect run, don’t bother burning fuel.

We had a team meeting before we left. Matt said he was going to look for newer tyres, to see if that was the cause of the fishtailing. The data showed that the engines need more fuel to make the power for a record run, but the standard coils that were fitted weren’t man enough to deliver a spark that could ignite the additional fuel, so they have to fit different coils. We said our goodbyes, not knowing when we’d be back. Matt was going to travel back to Bonneville within the week to see if he thought the salt would be good enough for the attempt that was planned for late August, but he didn’t seem hopeful.

With that one and only run on Tuesday, we were all done before nine in the morning on the last day, so the TV lot had me visit Wendover’s little library to do some bits for the programme, before I went back to the hotel to do some more work on the book. I was flying home the next day, but I still had one more thing to do on Bonneville Salt Flats first.