The Sweet Pork Company is rewriting the rules of pork farming and consumption in Australia. In the past, consumers have been led to believe that the leanest cut of pork is preferable, under the misconception that fat is always bad. This pressure pushed farmers to produce pork that was extremely lean. ‘The problem with that,’ Joe explains, ‘is that it tastes like cardboard. All the flavour of meat is gleaned from the fat. If you put chicken fat into beef sausages, they taste like chicken.’ Pork reared to be low in fat is often tough, dry and lacking in flavour. It was this realisation that paved the way for Byrne and Berting to develop their unique pork product.

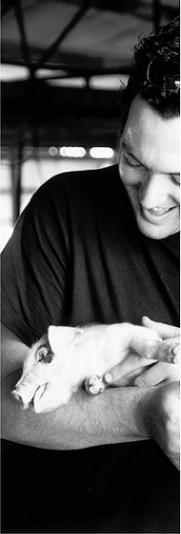

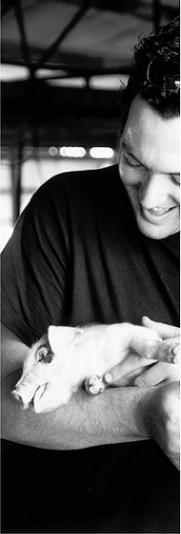

The Sweet Pork Company pays great attention to the feeding and management of farm livestock, in the belief that this close proximity will lead to a better product. Berting has lived in the Bangalow area since 1980 and has spent the majority of this time refining pig feed. The three farmers currently producing pigs for the Bangalow Sweet Pork are well versed in Berting’s secret feed recipe but have signed non-disclosure agreements. Although Byrne and Berting won’t reveal what goes into the feed for their pigs, they’re only too happy to discuss what doesn’t.

You won’t find growth promoters, antibiotics or chemical metabolism modifiers in the animals at the Sweet Pork Company. These are used elsewhere to prohibit the development of fat in the animals, to speed up the growth process and therefore the meat yield. Similarly, fish meal is commonly used elsewhere in feed. While extremely high in protein and helpful in producing a very lean carcass, which has been in fashion in recent years, fish meal tends to make pork meat taste fishy. ‘It’s simply not what pork is supposed to taste like,’ Berting says.

With the policy of avoiding all chemicals in the meat and allowing the pigs a more natural diet and a longer, gradual weight gain, Sweet Pork has a high fat content and is a more expensive cut of meat. But for the exemplary taste and delicate texture, it is very much worth it.

‘Pork used to taste wonderful when I was a kid, but this paranoia about fat nowadays has spoiled how pork is meant to taste,’ Byrne says. He is keen to educate his customers to change their priorities. Along with Australia’s obsession with fat, the problem is, according to Byrne, a lack of understanding and experience in pig farming. Old methods have been lost to mechanised farming techniques and the philosophies that underpin those long-trusted techniques have disappeared.

‘Few of the newcomers to the industry in the past twenty years would have had the benefit of any experience in pig production that wasn’t in a “factory farming” situation,’ Berting says. ‘All research in feeding, breeding, housing and health is governed by the pressure – mostly from supermarkets – to produce a cheaper article, heedless of the quality. Worse still, the term “quality” has been misrepresented to mean “absence of fat”.’