“Women are not frail. By widespread consumer education, early lifestyle behavior modification, and the productive use of modern technology, the image of the shrunken little old lady we hope will be condemned to history and replaced by women imbued with vitality and a zest for an active and productive old age.”

—MORRIS NOTOLOVITZ, M.D., Ph.D.

I’m the third girl in a family of four girls. My sisters and my mother had serious medical problems (mostly cardiovascular) while they were alive and they have all died too young. I enjoy life, I want to be physically and mentally active. I don’t want to be sickly or to die young. This is the reason for my story.

In 1984 I was fifty-four years old, a widow for a year, and the mother of four adult children. I was enjoying my work with young people, my family and friends, and life in general; however, I sensed something was wrong with my physical condition. I had been diagnosed as having essential hypertension when I was twenty-nine years old. Over the years, physicians had prescribed a variety of medications, which usually kept my blood pressure below the 150/90 threshold. I was taking four different medicines for five or six years and my blood pressure was staying within normal limits. But I knew something was wrong. My body just didn’t feel like me. Everything was taking more effort than it usually did. I felt like I had to push myself to swim and play golf, my two favorite sports. I would go to aerobics class and really be working out well and never could get my heart rate into the target range. Very frustrating for someone who likes to follow directions and achieve my goals!

When I mentioned this to friends, they made the usual comments, “Remember you’re older now, VR!” I knew too many active people much older than I was, so I didn’t buy into my friends’ excuses. I went to my doctor, whom I’d been going to for seven years. I told him how I felt and suggested that I needed a reevaluation with an up-to-date cardiac stress test (remembering my sisters and their heart problems, it seemed like a reasonable request to me) and then a review of my medications. He looked over my record and said “No, there is no sign that you need a cardiac stress test. Your blood pressure is well-controlled and you seem fine to me.” I believe he thought this was true, but I think he was also influenced by the fact that I was on an HMO insurance plan and this would add to his medical expenses. He had indicated there would be problems justifying the cardiac stress test.

At this point I did some serious soul searching. I felt something was wrong with me physically. I knew I couldn’t prove it, but I wasn’t going to let a doctor keep me from getting a correct diagnosis! I thought about my mother and sisters. Mother started having heart attacks in her fifties, had two operations on her carotid arteries in her sixties, had strokes in her seventies and eighties, and died in a nursing home at eighty-five, out-of-touch with reality. My sister Rae, who was seven years older than I, started having heart attacks in her forties and died at fifty-one. My older sister Anne, who is ten years older than I am, started having heart attacks in her fifties, and at sixty-four had a quadruple bypass. She lived an invalid’s life until she died at age sixty-nine. With this kind of family history, I knew I needed help immediately.

I shared my story with Dr. Vliet. She asked many questions and then ordered a cardiopulmonary exercise test plus some labwork. My own primary care physician refused to order the test, saying I didn’t need it. I had never had such a comprehensive stress test. It was stopped suddenly because my condition rapidly declined. The test report stated I was heavily overmedicated, my heart was blocked so much by the beta-blockers that it couldn’t get to a higher heart rate even though the monitors showed that I had already passed the aerobic threshold! The cardiologist’s report said I was in danger of sudden death if I participated in physical activities. And here I had been pushing myself in aerobics classes three times a week. I knew my body had been trying to tell me something, I just didn’t realize how serious it was. Dr. Vliet urged me not to go on my planned wilderness hiking trip, but to take that time to get my medication changed and my body in better shape. After the abnormal results, my primary care physician then said, “Oh, well, I guess this did need to be done. I’ll send the prescription to the insurance company.”

I believe Dr. Vliet saved my life. She listened to my concerns and accepted the possible validity of them. She ordered the tests that would give her the factual information she needed to confirm or deny my subjective feelings about my body. Dr. Vliet did a complete re-evaluation and, with her colleague, provided me with a new regimen of preventive medicine and appropriate medications.

Now, eleven years later, I follow the basic tenets of preventive medicine: low-fat foods, regular physical activity, relaxation techniques, caring relationships, required medications, and periodic medical checkups. I have lost weight, yes, but more importantly I have gained good health. My blood pressure is controlled; I exercise four times a week. I take only two medications now, instead of five, and I am off the beta-blockers. I work full time in a high-pressure job I love, I go jet-skiing and swimming with my grandchildren, and have just taken up scuba diving. Good living for a sixty-five-year-old woman!

Update, 2000: VR is still active and energetic, still scuba-diving, exercising regularly, is taking even less medication, loves how good she feels on her estrogen patches, and has not had a heart attack like her sisters and mother. She is now over seventy but has the energy and vitality of someone twenty years younger.

VR wrote her story herself when she learned I was writing a book, because she wanted her voice to be heard by other women who may not be listened to, and wanted to encourage other women to listen to their own body wisdom. I feel gratified by her words and inspired by all that she has done to take charge of her life in spite of the “bad genes” she’s inherited! She has truly made the efforts that are within her control to change her lifestyle, move from FAT to FIT and healthy. Which will you be? You choose. There is a great deal that is indeed within your control.

VR’s story illustrates the many integrated issues I have raised throughout this book and encapsulates what has been wrong in women’s health care. She is an articulate, educated, health-conscious professional woman. She knew her body and trusted her instincts. She had appropriately consulted her physician with her concerns. She was not listened to, not taken seriously, not evaluated properly for her health history and risks. She was overly medicated and then told she was fine, there was nothing wrong. If someone this knowledgeable and assertive was dismissed and discounted, it makes it even more alarming to think about all the women out there who do not have VR’s knowledge and ability to speak out, and then quietly become more debilitated or die from not being listened to and taken seriously.

VR’s story is critical in illustrating another problem for women. Weight loss is key to reducing hypertension and heart disease risk. Doctors know that, but too often don’t refer patients for nutritional consultations to help with healthy weight loss plans. Instead they tend to prescribe pills to control blood pressure. It’s faster, it’s what they are taught, and many patients expect and want a “magic bullet.” But VR was different. She had been actively involved in a regular exercise program for a number of years, and she had worked hard to decrease her body fat, cut out added salt, reduce alcohol, and stop smoking. What she did not know, and what was potentially lethal, was that the very medications given to decrease her blood pressure were also directly interfering with her ability to lose weight and her ability to accomplish the benefits of her aerobic exercise. She had never been checked for hormonal changes, nor had any physician talked to her about the potential cardioprotective benefits of estrogen therapy so she could consider that option. She was on five different antihypertensive medications and cholesterol-lowering drugs when she came to see me, creating problems with drug interactions and side effects that were making it even harder for her to lose weight and have the normal body responses to exercise. Yet, her physician had never looked at the estrogen factor, which is so crucial to preventing heart disease in a woman with all these risk factors and strong family history. For the “bottom-line” folks out there, if you ignore all the quality-of-life issues for VR, and if you ignore the risk of premature death she was facing, and just look at the dollar cost of her care (over $500 per month on medications alone, in 1995 dollars), isn’t it far more cost effective to provide a woman-centered evaluation with appropriate testing of hormone levels, decrease her expensive medications, help her with lifestyle changes, and prescribe hormone therapy than to continue multiple medications and treat the complications, and heart attack, when these occur? Put in this context, a hormone blood test doesn’t seem so expensive, does it?

As I indicated above, beta-blockers (like Inderal, Corgard, Atenolol, Tenormin, and other newer ones as well) have several unwanted effects: (1) they slow down metabolism; (2) they decrease insulin release from the pancreas, which then impairs glucose regulation and increases the tendency to gain weight; (3) they block the normal heart rate response to exercise, which impaired VR’s ability to safely exercise and monitor her heart rate; (4) they decrease one’s energy level and tolerance for physical activity; and (5) they interfere with normal thyroid hormone function. Here was a well-motivated and disciplined patient who was being thwarted in her efforts to achieve her health goals due to ignorance of the unappreciated side effects of the medication she was taking.

Let’s look at some other gender-specific issues and needs for women who are making the transformation from being overfat to being more fit and more lean—notice I didn’t say skinny, I said fit and lean.

Since estrogen and progesterone are both involved in regulating metabolism, blood glucose, and body-fat storage, you’d think that researchers would have paid more attention to the “female factor” in obesity research. If you and your husband or boyfriend have ever gone on a diet at the same time, you have experienced firsthand that weight loss is very different in men and women. A few years ago, when my husband and I went on a spa vacation, I watched him peel off the pounds, while I struggled to get a quarter pound lower on the scale. He even got to eat more calories than I did. Not fair! From an evolutionary perspective, it makes sense that females would be more efficient at storing (and keeping) body fat, to carry pregnancies. Now we live in a culture that esteems thinness and at the same time makes eating a dominant social activity, rewards good behavior with ice cream or candy, and puts fast-food options on every street corner. What insanity. Our bodies have not had several million years to adapt to the sudden availability of excess food, and we pay the price with an obesity epidemic in the United States.

Sugar and fat are two examples. I lived in Williamsburg, Virginia, for many years, and I was surprised to learn that in colonial American homes, sugar was such a rare and very expensive delicacy that it was often kept under lock and key. Today, we truly live “la dolce vita” (the sweet life) when we put sugar in practically everything, even ketchup. Pounds of it, in fact. Today the average American consumes on average 125 pounds of sugar per person per year. That’s incredible. Much of the sugar we eat is hidden. It appears in processed foods of all kinds, including soups, condiments, salad dressings, frozen dinners, and the obvious sources: desserts and soft drinks. It’s been calculated that the average American eats 24 percent of daily calories from sugars in various forms, mainly refined sugar (sucrose). Then comes the FAT. Americans consume, on average, 40–43 percent of daily calories from fat, instead of recommended amounts of 20–30 percent. That means 64 percent of the calories you eat every day come from fat and sugar. No wonder Americans have more obesity and obesity-related diseases than any other country in the world. Since simple sugars have no nutritional value except providing energy, that means that most Americans have to get the essential nutrients from only 35 percent of their food intake. It is clear that sugar and fat calories are crowding out more nutritious food groups from our diet. And for women, sugars especially pack a double whammy: eating them tends to create a vicious cycle of craving them, and our hormonal changes each month affect not only how our bodies metabolize both sugars and fats but our cravings for them as well. I will talk more about these vicious cycles further along in this chapter. But first, some metabolism basics as related to women’s bodies.

Fat storage is one of our adaptations to the scarcity and unpredictability of food supplies before food was cultivated on a steady basis. Humans who were more efficient at storing body fat were better able to survive the periods of famine. Pima Indians in the southwestern United States are an illustration of the consequences that occur when people have evolved in environments of scarce food, and are genetically more efficient at storing fat. Now that foods, and the wrong types of food, are so plentiful, Pima Indians have the highest incidence of diabetes (and all its complications) of any group in the United States.

Females in particular needed to be able to effectively store fat in order to survive and to also provide the nourishment to sustain a growing fetus for nine months. Estradiol helps to regulate blood sugar to keep glucose levels steady, and it also functions to enhance storage of fat around the hips, thighs, and buttocks, which provides “fuel” able to sustain a pregnancy. Progesterone causes increases in appetite and metabolic rate and also causes lowered sensitivity to insulin that increases fat storage and leads to glucose intolerance, and further increased cravings for sweets. This effect of progesterone encourages a pregnant woman to eat more, which results in better nourishment for the fetus; but alas, more body fat for the mother.

Recent research has confirmed what women have always suspected: We get hungrier the week before our periods, due to the rise in progesterone. Appetite increases about 12 to 15 percent in the second half of the menstrual cycle. If you ignore this increase in appetite because you are dieting, you may find that the sweet cravings become uncontrollable, leading to the binge-on-sweets-feel-guilty-starve-again-then-binge-again cycle. If you eat fruit and whole grain breads high in complex carbohydrates, balanced with more fat and protein, during the progesterone-dominant second half of the menstrual cycle, you provide the fuel needed to sustain blood glucose during this time of increased appetite and metabolism. The result is you are less likely to give in to the craving for sweets that lead you to overeat, the main culprit in adding excess pounds.

Compared to men, women also have more of the lipogenic enzymes that help the body store fat instead of the lipolytic enzymes that break down fat so it can be used as fuel. Many of our female tendencies to gain weight and to crave sweets (instead of meats, which men tend to want) have strong hormonal influences that have an adaptive advantage for our species. Unfortunately, our biochemical makeup just doesn’t fit well with our current cultural obsession with women having to be rail thin to be considered sexy and attractive. It helps to understand these basics so you don’t fall into the psychological trap of beating yourself up mentally because of your body size. You can help improve the ratio of lean muscle mass to fat mass by exercising regularly and eating healthy. As you read further, I will explain ways of achieving a better balance in what and when you eat, the difference between body weight and body composition, as well as the ways female hormones interact with appetite regulation.

I am not perfect. I have been FIT. I have been FAT. I have probably in my lifetime tried almost every diet that came out. Finally I learned some years ago that most diets don’t work. What works, plain and simple, is healthy eating with the optimal balance of protein (about 25–30 percent), fat (about 25–30 percent, focusing mainly on unsaturated fats), complex carbohydrates (40–50 percent), along with increased activity and regular exercise. Do I always do it? Not always. I’m just like most of you: too many things to do and too little time to do them. Until 1989 and the last round of surgeries on my neck, followed the next year by my hysterectomy, I had been really diligent about keeping up with exercise and maintaining my healthy body composition. I have to admit, since then it has been much harder. The many months of recovery from surgery got me out of my exercise routine so long, and contributed to enough weight gain, that I have had a very difficult time reestablishing a consistent exercise program that works as well as what I was doing in the past. I got bored with a basic walking program, and about a year ago, took up roller-blading. I loved the exhilaration and it was great exercise, but I forgot I was no longer the limber twelve-year-old who could fall with impunity. I also learned that roller blades are very difficult to control. After a spectacular crash (landing of course on all the places that did not have the protective pads) that messed up my shoulder, hip, and neck, I am now back to a more sane exercise regimen of either walking on the treadmill or swimming laps five to six days a week. Walking and swimming are not as exhilarating for me as jogging or roller-blading, but they are a lot safer! And this amount of exercise does help keep excess weight in check. I also make an effort at work to walk up stairs instead of taking elevators a few floors, and I look for ways to walk more during daily activities. Every little bit helps. I really do understand the frustrations and difficulties my patients describe in reaching their goals, since I’m right in there fighting the same battles.

But I will say this: over the last twenty years, in an effort to better practice what I preach and to be healthier myself, I have made some significant changes in the way I eat. I have much less saturated fats. I make sure to have a good balance of protein at each meal and snack to help decrease the insulin surge and blood-sugar drop that come with high-carb snacks. I rarely use butter or margarine, or even much vegetable oil. I used to make homemade mayonnaise, I enjoyed it so much. Now I prefer using nonfat yogurt or low-fat mayonnaise. I have red meat only a few times a month. I cut out colas (even diet ones) and other soft drinks with phosphates. I rarely have any alcohol, maybe a glass or two of wine every several months. I have cut out added salt and pick low-salt options when I eat out or buy a prepared frozen dinner. I don’t snack on sweets like I used to. I eat more fresh fruit. I eat whole grain bread. I eat only plain popcorn, no butter and no salt. I don’t go to work without a good breakfast anymore. I make sure I keep up with my skim milk for calcium without the fat of whole milk. I pay attention to taking magnesium supplements and a multivitamin every day. Taking this inventory really helped me to affirm the positive changes I have made. You might do the same.

Take an honest look at what you eat every day. Can you find some healthy changes you have already made? Good. Make a list of those, and add three or four new ones. Think of changes to add that you are ready to make NOW.

As we baby boomers age, one thing is clear: We are getting fatter. Entrepreneurial types have quickly figured out that there is a huge market here and lots of money to be made with diet products of all types. The hype is everywhere, and there are figures to show we are buying into the hype: Americans spend close to $40 billion annually on diet and diet-related products. The sad part is, 95 percent of people who are buying into all these diets will regain the weight. This creates the marketing opportunity of the millennium: selling the same product to the same people over and over again. Fads in food abound. Fads in diets crop up faster than the weather changes. New diets sell products: books, tapes, flash cards, videos, cookbooks, supplements, special foods, prepared meals—you name it and there will be a product designed to go with the newest “diet of the day.” There’s a diet to suit every taste and every food craving. High fiber, low fat. High fat, low fiber (good if you like being constipated). High protein, low carbohydrate is in. No, it’s out. High carbohydrate, low protein is the way to go. Don’t mix protein and carbs at the same meal. Don’t mix fruits and vegetables at the same meal. Don’t mix protein and fat at the same meal. Don’t mix protein and fruits and vegetables at the same meal. Eat grapefruit at each meal to burn fat. Don’t eat grapefruit, it will cause stomach acid. It would be less confusing to just not eat. 1980: Margarine is OK, butter’s bad. 1990: Margarine’s bad, butter’s better. 2000: Flaxseed oil and Benecol are the way to go.

How do you make sense of all this? (My suggestion: Don’t try. It doesn’t make sense, it just sells.) How do you sort out fads from facts and find something that works for you? I will hit the highlights here, and I have to admit this section on food balance has changed significantly since I first wrote Screaming to Be Heard in 1994. At that time, I was still heavily influenced by the emphasis on low-fat, high-carb meal plans based on programs such as those of Drs. Ornish and Pritiken. As time has gone on, and I have done more clinical work with women’s hormone changes and their effects of “apple-shaped” weight gain leading to insulin resistance and further weight gain, I have had to modify my original emphasis on the low-fat, high-carb approaches. One crucial factor I had not fully realized at that time was that the positive findings of Pritiken and Ornish with regard to low-fat, high-fiber, lower-protein diets were based mainly on studies of their male patients. As we women all know, there are a lot of differences between men and women in terms of fat storage, and loss/gain of fat and body weight, particularly those of us who are in the midlife years or those with abnormal ovarian function such as PCOS.

The emerging data on insulin resistance in women, and the impact of our midlife decline in estradiol, with normal progesterone and relatively more androgen effect, has led me to modify my earlier recommendations of a diet consisting of 60 percent carbohydrates, 20 percent proteins, and 20 percent fats. I now recommend for my patients (and for me, too) a meal plan higher in protein along with healthier fat sources. The earlier emphasis on very low fat (20 percent or less) and high (60 percent or more) carbohydrates works well for men, but not as well for women with the hormonal changes of PMS, PCOS, perimenopause, and menopause. For a while, until periods actually stop, women going through the premenopausal ovarian decline are losing estradiol (E2) first, but progesterone (P) is typically still in the ovulatory range. This means a higher P to E2 ratio, which along with the “unmasking” of male hormones (androgens) due to decline in E2, tends to put weight gain around our waist and upper abdomen. This change in fat distribution makes us tend to be less sensitive to insulin, a condition called insulin resistance, which promotes fat storage.

There is also another whole dimension to the way hormonal changes in women affect insulin regulation, which makes the syndrome of insulin resistance much more common in women, especially as they grow older. Insulin resistance refers to the phenomenon of having high levels of both circulating insulin and glucose in the bloodstream, but the insulin molecules can’t bind properly to the insulin receptor sites on the surface of the cell to allow glucose to enter the cell and be used for energy. This occurs when women (and men) gain weight; the fat cells become distorted in shape with increased fat storage, and the “lock” or receptor site for insulin is “warped” out of proper alignment, so the insulin molecule “key” no longer fits in the receptor. Insulin resistance makes it harder to lose weight, since the cells are not getting enough “fuel,” you continually perceive you are hungry even though there is plenty of fuel circulating in the bloodstream. It also causes rising blood pressure and problems with “reactive hypoglycemia” (low blood sugar) when the excess insulin suddenly works, glucose rushes into the cells, and your blood glucose plummets. This sequence creates intense sweet cravings, and the whole cycle starts over; you get fatter, become more insulin resistant, and so on. Such marked glucose swings contribute to feeling lethargic, sleepy, and having trouble concentrating when the glucose levels are rising, and then feeling sweaty, anxious, irritable, or weepy when the glucose levels are falling quickly. You may notice significant changes in how you feel and function relative to the time since your last meal or the types of food you eat. Insulin resistance is one of the “deadly four” that increase the risk of heart disease and diabetes, along with truncal obesity (waist area instead of hips), high blood pressure, and high cholesterol/triglycerides.

It is now known that there are also insulin receptors in ovary tissue, and insulin appears to change the enzymes in the ovary to shift hormone production toward the androgens rather than the normal estrogen balance. This type of problem occurs in young women with PCOS, and in perimenopausal woman who are losing estradiol. The imbalance of androgens to estradiol causes deposits of body fat around the middle of the body (similar to males), as well as all the other unwanted effects I just listed. Low-fat, high-carbohydrate diets make this problem worse by stimulating more insulin production by the pancreas, and more insulin production in turn tends to push the body toward storing more fat. More body fat then makes more insulin resistance, so it is another of those terrible vicious cycles. Some of you may see yourself and your own struggles in this description. This is why I have revised my earlier recommendations on the balance of carbohydrates, fat, and protein to help reduce this trend toward increased insulin resistance.

I suggest that you read the book 40-30-30 Fat Burning Nutrition by Joyce and Gene Daoust, for more information on insulin resistance that occurs for us as we gain weight and experience the midlife hormonal changes. This excellent book will also provide suggestions on meal plans for you that are quick, simple, and easy to follow. Another good book on this subject is The Protein Power Plan, but my patients have told me that it is harder to follow than the 40-30-30 book. In order to decrease the stimulation of insulin with meals, I recommend that you aim for a blend of 40–50 percent complex carbohydrates, 25–30 percent protein, and 25–30 percent unsaturated fat with each meal.

It is also important to focus more on foods with a lower glycemic index to help avoid overstimulating insulin production that in turn triggers more food stored as body fat instead of being burned for energy. What does glycemic index mean? Food that are quickly converted to glucose, such as bananas or white flour pastas and breads, cookies, crackers, and sweets, have a high glycemic index. Food that take longer to be converted to glucose, such as fat and protein foods or fibrous vegetables, have a low glycemic index, and do not overstimulate insulin production. Lower insulin levels help you lose the unwanted body fat, as well as reduce your risk of heart disease and diabetes.

I also recommend smaller meals at more frequent intervals to help maintain your energy level on an even keel throughout the day, increase metabolic rate, and reduce food cravings later in the day. Mood, anxiety, and cognitive changes are quite characteristic of the brain effects of marked glucose fluctuations due to elevated insulin and falling estradiol. These are the same symptoms women with FMS describe as “fibro-fog,” which can actually have many hormonal and nutritional causes. In addition, the symptoms we use to diagnose panic disorder are the same symptoms that are triggered when the brain’s “alarm center” senses a rapidly falling glucose or estradiol. It feels the same, even though the cause may be quite different. The more you can achieve stable glucose and estrogen levels with diet, exercise, healthy hormonal balance, and, when appropriate, use medication options such as metformin (Glucophage), the less you will need antidepressant or antianxiety medicines to improve mood and decrease anxiety symptoms. Low-to-moderate-intensity exercise, such as walking, acts as an “invisible insulin” that serves to facilitate delivery of glucose to the muscles and lower the tendency to have high glucose levels in the bloodstream. It also decreases the problem of insulin resistance and helps burn fat for fuel as well as improving muscle function.

Let’s take a closer look at these food types, or “macronutrients”—carbohydrates, proteins, and fats. Carbohydrates are one of our key nutrient groups. You’ve heard the term a lot. It used to be that all the magazines talked about cutting out the “fattening” carbohydrates. Then for a while, all we heard was “carbs are good, it’s the excess fat we put on them that is bad.” This idea focused on all the sour cream, butter, oils, and mayonnaise that were added to foods like baked potatoes or pasta or salads. For example, a baked potato with sour cream and bacon bits and butter could run 500–600 calories, while a plain baked potato has only about one hundred calories yet is loaded with fiber, vitamin C, minerals, and lots of energy. But, now we are coming full-circle to having more books recommending lower carbs and a little more fat (of the healthy kind) again.

Carbohydrates are the body’s primary “quick-start” fuel, providing four calories of energy per gram. Carbs are readily converted into glucose, the only fuel the brain can use. Proteins are a little slower to undergo this conversion to glucose, but, they, too end up in the bloodstream as glucose that gives our brain and body the steady fuel it needs to operate. If you aren’t getting enough carbohydrates and protein at regular intervals throughout the day, your blood sugar falls, and you feel tired, irritable, and foggy-brained. Both protein and carbohydrates are crucial elements of your “eating well” plan to maintain energy, concentration, memory, stable mood, and a normal metabolic rate throughout the day.

Complex carbohydrates, such as whole grains, whole vegetables, and whole fruits, are your best source but should make up only about 40–50 percent of your daily food intake. Choosing complex carbohydrates over simple carbs such as white-flour pasta, white bread, or crackers will provide more fiber, better stability in your blood glucose, and a healthy feeling of fullness so you won’t have the desire to overeat. Complex carbs also don’t tend to overstimulate insulin production as much as simple carbohydrates do. In addition, bringing in more of a balance of proteins and fats at each meal, provides better feeling of fullness (satiety), and sustains your energy levels more evenly and longer.

Proteins also provide four calories per gram as energy for the body. Proteins are slower to digest than carbohydrates, so they help keep blood sugar (glucose) levels steady over about three to four hours, compared to the shorter length of time, about one–two hours, that blood glucose is sustained by complex carbohydrates. The role protein plays in our food is to supply the amino acids from which the body can make its own proteins. The protein in food and the resulting amino acids help keep blood-sugar levels steady over several hours, compared to the shorter interval sustained by complex carbohydrates. This is why a healthy balance of protein—about 25–30 percent of your food intake—is important at every meal. Protein is needed for building healthy muscle and bone and for body-repair processes, such as daily muscle repair, particularly as you increase your exercise. Proteins also provide the building blocks to immune globulins and the brain’s chemical messengers.

Amino acids are classified into two categories: those the body can make and do not have to be included in the diet, called nonessential, and those the body cannot make itself and must get in the diet, called essential. There are eight essential amino acids that the body is not able to make, or can only make in very small amounts not fast enough to meet energy demands. One essential amino acid of special interest to women with pain syndromes is DL-phenylalanine (DLPA), an amino acid with mild pain-relieving properties. It is found naturally in foods such as nuts, cheese, avocados, bananas, sesame and pumpkin seeds; it is also available as a supplement sold in pharmacies and health food stores. However, if you are taking MAO inhibitors or have migraines, hypertension, palpitations, or tachycardia, you should not use DLPA supplements. Another essential amino acid is lysine which the body uses to manufacture L-carnitine, a chemical that helps muscle cells to more efficiently use oxygen. Tyrosine is a nonessential amino acid that your body is capable of synthesizing on its own and is used to make both adrenal and thyroid hormones. Are you beginning to see how your diet plays a role in your hormone balance and well-being?

Complete proteins are those that contain all of the essential amino acids and are found in animal sources, foods such as meat, fish, chicken, eggs, and cheese. But these foods contain higher amounts of fat, so you need to select those protein foods that are lower in fat: lean meats, low-fat cheeses, poultry without the skin, egg whites without the yolks, et cetera. If you do not eat animal protein, you need to combine your vegetables in such as way that you get complete proteins, since vegetable sources are lacking in some of the essential amino acids. The combination of beans and rice to make a complete protein source is an excellent example.

Fats are the most concentrated energy source in our macronutrient group, with nine calories of energy per gram. Some fat in the diet is crucial to provide the essential and other fatty acids that are used to make a variety of hormones, including those of the ovaries, as well as to absorb fat-soluble vitamins. I don’t think the extremely low-fat diets are as desirable for women, but neither am I giving you license here to throw away all concerns about eating fat, especially the unhealthy saturated or “trans” fats. Actually, I find that if I use just the fat content of my protein sources and don’t add much fat to what I eat, I’m generally pretty well on target with the 25–30 percent percent fat goal. As you can see from various calorie tables, you certainly don’t need butter or margarine on your grilled cheese sandwich, since the cheese has more than adequate fat content on its own. Most Americans certainly exceed my recommendation of 25–30 percent fat intake.

If you want to maintain health, lose weight successfully, and maintain a healthy body weight, the “secret” is to cut out the excess fat in your diet and get your body moving more. Nothing new, I know, but the good news is that cutting out the excess or added fat is also one of the easiest ways to reduce your total caloric intake. Most people don’t realize that all fats (whether vegetable oils, olive oil, butter, margarine, or lard) have twice as many calories per gram as carbohydrates and protein (9 cal/gm compared to 4 cal/gm each for protein and carbs). Fat is the most calorie-dense type of food we eat, but high-fat foods don’t take up space in the intestinal tract like high-fiber foods do, so we often don’t realize how much fat (and calories) we have eaten. It is dramatic how much more dietary fat Americans eat now than we did at the turn of the century: 45 percent now versus 28 percent in 1900.

A primary source of dietary fat for most Americans is the hidden fats in foods that often sabotage our best efforts. The new food labeling will help you detect these hidden fats, such as the salad dressing on your salad, the cream sauce on your pasta (remember that marinara sauce is lower in fat), the olive oil for dipping your bread, fish cooked in butter, donuts at the morning coffee break, pizza dripping with cheese and pepperoni, French fries, those big yummy-looking “bran” muffins (there’s probably a day’s worth of sugar and fat in each one and not much bran!), the sauce glistening on your steamed vegetables, the list goes on and on. It helps to learn where the fats are hidden in various foods and gradually cut back every day. You may find it helpful to buy a small paperback guide to counting fat grams, since there are now several good ones available. Consider it as “lite” reading. As you make these changes, tell yourself all the wonderful things you are doing for your body, now and down the road. You’ll also notice you don’t feel as sluggish. Diets that are too high in fat and are not balanced with proper amounts of carbohydrates and proteins slow down the gastrointestinal tract motility, contributing to more constipation, distention of the tummy, and feeling generally fat and miserable, especially the second half of the menstrual cycle.

The real key for women going through hormone changes, such as PMS or PCOS or perimenopause, to help maintain steady energy levels, improved brain clarity, and less pain is to achieve a balance of carbohydrates, protein, and fat at each meal and each of the “snack breaks” of the day. For example, this is why I recommend having a healthy snack in the late afternoon, about 4 PM, when blood sugar normally hits the “afternoon slump.” This snack should also have the balanced ratios (40:30:30 or 50:25:25). Making sure you do have this late afternoon snack each day helps your mental sharpness and also helps keep you from coming home from work ravenous and eating everything in sight. Depending on what time you get your breakfast in, I also suggest a mid-morning snack to keep things level.

While I am on the subject of dietary fat, I want to comment about another disturbing trend I have seen in women’s health habits. I encounter more and more women who tell me they have cut out dairy products, especially milk, for fear of the fat. What do they replace milk with? Typically, it’s soft drinks, whether regular or sugar-and-caffeine free. Either type poses unique problems for women who want to be healthy and maintain optimal body composition and bone density. All soft drinks contain high levels of phosphates, which attach to the calcium and magnesium ions in the digestive tract and increase the loss of both minerals from the body. Calcium and magnesium then move from the bones to maintain adequate blood levels that are needed for normal nerve and muscle function. So the more soft drinks you consume, the more calcium and magnesium you lose. Regular soft drinks not only leach these minerals from your bones, they are also loaded with sugar. A twelve-ounce nondiet soft drink contains about seven to eight teaspoons of sugar. This becomes a real problem when you drink five or six sugared sodas a day, because you end up with almost half your total daily calories coming from a source without any nutritional value! If you drink the sugar-free ones, you are still getting artificial sweeteners whose sweet taste contributes to excess stimulation of insulin, a hormone that stimulates fat storage. Think about it. Low-fat milk has about the same calorie content as a regular soda, and rather than leaching calcium from your bones, it provides both calcium and protein. I have been drinking skim milk for so long that 2 percent milk now tastes too rich.

Another gimmick to watch out for is all of the low-fat and fat-free food items now filling the shelves. The fat may have been removed, but it has been replaced by simple sugars and excess calories with little nutritional value. These play havoc with blood-sugar levels that in turn affect energy levels. Plus, what I find is that because the box of cookies is “fat free,” we feel psychologically it is okay to eat more. How many of us have come close to finishing a whole box of these in one sitting . . . or just deciding that there are not enough left to bother with putting them back in the pantry? That is not a balanced snack . . . and it is a sure way to increase insulin production and promote more storage of body fat.

Most women I talk with are absolutely obsessed with the scale and what they weigh. Body weight has become the number one statistic women talk about, certainly in large part due to the cultural brainwashing that to be thin is to be desirable and acceptable as a woman. I want to emphasize that we really should be looking at body composition rather than body weight. Body weight can vary immensely depending upon how much muscle mass you have built up and what your body build is. Someone who has a heavier bone density, for example, and more lean body mass may weigh twenty-five pounds more than a smaller-boned person who has not been exercising, and yet both could have the same percentage of body fat. One patient of mine is a young petite, thin woman (size 4) who is sedentary. Her body-fat anaylsis showed that she has 34 percent body fat. Healthy ranges for women over 30 are about 25-30 percent body fat, so this woman is in an unhealthy “at risk” range, although she looks terrific by society standards. Another patient, who is stockier in appearance and wears a size 14, actually has 25 percent body fat because she exercises regularly and does weight training three times a week. The second patient, who wears a larger size, is actually healthier overall than the smaller size woman. Fit doesn’t mean skinny.

I recently went to my husband’s class reunion, and someone remarked that though she wore the same size dress that she had in her twenties, the form inside was much different. One of the things that changes with age is body composition—the relative proportion of fat to muscle, bone, and other lean tissue. In the ongoing Fels Longitudinal study on aging, researchers looked into this. A brief summary shows that both women and men in the study had age-related increases in weight, total body fat, and percentage of body fat during the period from 1976 to 1996. Those who had the higher levels of physical activity predictably had lower percentages of body fat. Women generally experienced a change in body composition rather than a loss of weight or reduction in body mass. Menopause also made a difference. The longer a woman had been postmenopausal, the higher the proportion of body fat to lean body mass; however, those who took estrogen lost less lean body mass, and had a lower body-fat percentage. For postmenopausal women wishing to maintain healthy body composition, the equation then seems to be Ex + E2 = a healthy body. That is, exercise helps a lot, plus the right type of estrogen helps exercise be more effective in building bone and muscle.

The way to really determine an optimal weight for you is to have a body composition test done to measure your percentage of body fat. For women the optimal ranges are 22–30 percent body fat. If you are over thirty, you are more likely to preserve bone if your body fat is closer to 25 percent. The “at risk” range is greater than 33 percent. If you’re over age thirty and you’re trying to get down below 20 percent body fat, you really do increase your risk of osteoporosis. This is because you’re losing enough body fat to lose some of the natural estrogen that’s present in body fat tissue, and you begin to actually have some negative effect on your overall health.

Research at the Cooper Clinic, from the National College of Sports Medicine, and other investigators studying optimal healthy ranges, has found that when women get too low on percent body fat, they stop menstruating normally, have declining hormonal production, and begin to lose bone more rapidly. I really strongly encourage women not to go below the 20 percent body-fat level. Actually, if you get down below about 15 percent, you lose menses and that’s when women become even more at risk for osteoporosis. Those of you on a weight-loss regimen, and who are exercising several times a week, should focus on body measurements once a month and not be obsessed with body weight. Your weight is not going to be an accurate indicator of the loss of fat tissue (which weighs about  as much as does muscle tissue). It is much more accurate, and helpful, to focus on how your body is changing in the way of inches. This gives you a much better picture of the amount of fat loss. As you exercise you increase the lean body mass, so by only using scale weight measurement you won’t realize that you’re losing “light weight” body fat as you build up heavier muscle mass. I usually recommend to women that they take their body measurements about once a month, and try not to weigh on the scale any more than once every other week. You can go tomorrow to your local health club and have your body-fat percentage measured. Then throw your scale away, and buy a tape measure. Focus on what’s happening to the health of your body, not on the number of pounds!

as much as does muscle tissue). It is much more accurate, and helpful, to focus on how your body is changing in the way of inches. This gives you a much better picture of the amount of fat loss. As you exercise you increase the lean body mass, so by only using scale weight measurement you won’t realize that you’re losing “light weight” body fat as you build up heavier muscle mass. I usually recommend to women that they take their body measurements about once a month, and try not to weigh on the scale any more than once every other week. You can go tomorrow to your local health club and have your body-fat percentage measured. Then throw your scale away, and buy a tape measure. Focus on what’s happening to the health of your body, not on the number of pounds!

Over my years of clinical practice, I would say that about 75–85 percent of women patients have described cyclic food cravings that are clearly related to the second half of the menstrual cycle. And these cravings are the kind of intense urges that override rational awareness that junk foods aren’t healthy! Women have often described going out late in the evening just to buy chocolate (or something salty or whatever) because the craving was so strong. I have to admit, I did that myself on occasion when the premenstrual “have-to-have-chocolate” urges hit! Why is this? And why is it that I have never had a male patient describe cravings for chocolate the way women do. Yes, I have had male (and female) patients who were alcoholic describe cravings for alcohol, but I see that as a different physiological issue and mechanism.

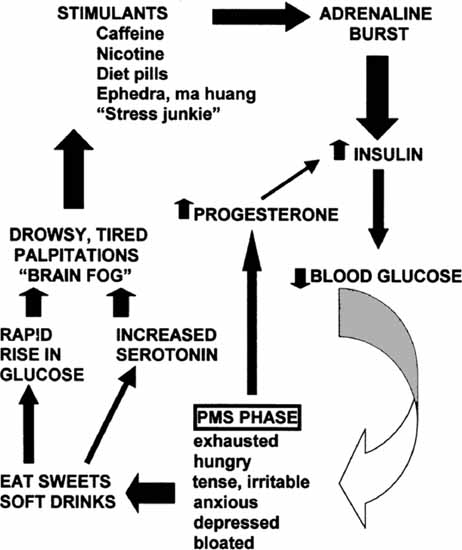

I think there is a key hormonal factor that affects women and contributes to these cravings: the rise and fall in progesterone during the second half of the menstrual cycle. How does this work? Progesterone alters the normal insulin response, which regulates blood glucose (“sugar” levels in the blood). Women then experience a greater tendency to have lower blood glucose levels, and more episodes of “reactive” drop in blood glucose following food intake, especially if the food intake is primarily sweets or other simple sugars. This tends to set up the vicious cycles that I have drawn in the diagrams below. Take a look at “The Vicious Cycle” and “Another Vicious Cycle” and see if you recognize yourself! Then read on about what is happening as your body cycles hormonally each month.

THE PMA VICIOUS CYCLE

© Elizabeth Lee Vliet, M.D., 1984, revised 1995, 2000

Not too long ago, I came across a newspaper notice in bold letters, like this:

THE NUMBER ONE CAUSE OF KITCHEN DEATHS IS EATING AN ENTIRE TUBE OF CHOCOLATE CHIP COOKIE DOUGH . . . RAW!

I howled with laughter at this. And so do audiences of women when I give a talk and show this slide. Most of us who have ever craved chocolate can relate to this, especially premenstrually.

Do any of you have cravings for chocolate? It turns out that the premenstrual rise in progesterone with its benzodiazepine-like effects on the brain may make you feel a little more slowed down, and several compounds in chocolate have mood-lifting, “feel-good” properties: the stimulants phenylethylamine (PEA) and theobromine (like caffeine), and magnesium. Newer research has shown that chocolate also contains calcium and antioxidants. Dark chocolate contains more antioxidants than green or black tea, while milk chocolate contains about the same amount of antioxidants in black tea. Brain levels of serotonin are also boosted by the sugar added to chocolate to make it taste good, so it’s no wonder that chocolate makes you feel good when you eat it.

I know I certainly lived with those chocolate cravings for a lot of years. Loss of the ovary cycles (and that progesterone rise), stable optimal estradiol levels, and good magnesium intake all combined to solve that awful cyclic craving problem for me. I know how it is: When you are feeling exhausted, hungry, tense, and irritable, sweets and chocolate are quick and easy to turn to. Alcohol, too, is digested to a simple sugar, causing a rapid rise in blood glucose, so women who have premenstrual alcohol cravings are also experiencing a physiological effect of the hormone shifts. Eating sweets in turn causes an increase in serotonin in the brain. If there is too rapid a rise in brain serotonin, it causes drowsiness, palpitations, and nervous/anxious feelings. A more gradual rise in serotonin can cause a sense of calming, much like a tranquilizing medication. Actually, sweets are nature’s original “tranquilizing drugs.” I’ve had patients say to me, “Well I don’t want to take an antianxiety medicine or antidepressant. I don’t want to take any drugs.” So I’ll turn this around and observe, “Did you realize you’re using food as a drug? Let’s look at a way to help you achieve your desired ends more constructively.” When you’re feeling drowsy and you’re trying to get through the afternoon, you often turn to what’s quick and readily available: caffeine, sweets, or maybe the nicotine in cigarettes. These all trigger release of the chemical messengers that affect insulin, which in turn drops the blood sugar, and there goes the cycle again. Sound familiar?

In summary, the vicious cycles you’ve experienced premenstrually are physiologically based in the hormone shifts, aggravated by external stressors, and intensified by the wrong food choices and lack of exercise. Then we get into the vicious cycle of poor nutrition, which in turn affects our body’s resistance to stress, which increases our craving for sweets, which affects the serotonin and insulin levels, which affects one of the brain hormones that regulates fluid balance. So there’s more fluid retention, which is also an effect of insulin; the kidney holds onto water and salt, and you feel bloated, headachy, and irritable. Sound familiar?

Perhaps you are now seeing some places in the “vicious cycle” where you can make a choice for types of food or exercise that will break the cycle, not intensify it. But, if you don’t know the vicious cycle is there, and how it works, then you can’t deal with it constructively. That’s my fundamental message: knowledge of what is happening gives you the power to make new and healthy choices. Be aware that when you’re feeling bloated, irritable, and headachy, you don’t feel like going out to exercise, yet that’s the very time you need it the most. You also don’t feel like fixing or eating a nice balanced meal with lots of steamed vegetables, but again, that’s exactly what you need. You have the power to perpetuate the vicious cycle or break it!

It has been described since the 1930s, and perhaps even earlier, that women have altered glucose regulation in the luteal (progesterone-dominant) phase of the menstrual cycle. There are many complex metabolic effects of the hormonal shifts and complicated interactions of the various neuroendocrine “regulator messengers” that control body weight, fluid balance, appetite, food cravings, and other functions. In this discussion, I have presented a very simplified overview of some of the key factors. There are a number of good books (see appendix II for ones I recommend) that go into more detail on these metabolic influences for women.

I have for many years been interested in the connections between physiological changes such as blood glucose, and hormones, and so on, and the kinds of physical and behavioral responses that such physiological fluctuations can trigger. I have done five-hour (and sometimes six-hour) glucose tolerance tests (GTT) on many women with PMS during the past twelve years, and have found a strikingly consistent pattern of an abnormal response to glucose if this testing is done in the mid to late phase of the second half (luteal phase) of the menstrual cycle. Many doctors have said to my patients “You don’t need to do glucose tolerance tests, we don’t do those anymore to diagnose diabetes,” or “It doesn’t matter when in your cycle you do a glucose tolerance test, it’s all the same.”

Well, I disagree with both aspects. First of all, I am not simply looking for diabetes, I am looking for objective laboratory data to show changes in glucose levels that correlate with my patients’ mood swings and physical symptoms and that could help explain the pattern of food cravings. Second, it is clear from listening to the patients that there is a definite cycle-specific characteristic to these cravings, and if I don’t do the testing at the time when the women have the cravings, then how will I discover potential physical and hormonal factors involved in triggering these cravings? Physiologically, the luteal phase of the cycle is when the hormone shifts have the most dramatic impact on the insulin-glucose regulations. If a glucose tolerance test is going to be done in a female patient, it is crucial to do it at the right time of her menstrual cycle to get the right information. The GTT should be done three to five days before the period is due. Timing of the GTT with the late luteal phase allows the best opportunity to pick up the way in which the hormonal shifts affect blood glucose regulation. This in turn helps me to individualize a dietary approach for that person, specifically when food is eaten and the balance of carbohydrate, fat, and protein that will best help that person.

If any of you have ever had a GTT to test for either diabetes or hypoglycemia, you know that patients usually go to the laboratory for the testing. No one except the laboratory technician observes the patient, and then the results (as numbers) are sent to the physician. Typically the physician looks at the individual numbers for each hour of the test, and if the numbers fall into the “normal” range, the patient is told “everything’s normal” regardless of how the patient may have felt during the test. Most patients are never asked if they had any symptoms during the GTT. It seemed to me that this process overlooked the most crucial information: what the patient had to say!

I developed a different way of studying this in 1983 and have been using this method in evaluation of women with hormone-related problems. I have the person come to our office for the GTT, and she (or occasionally, he) is shown how to keep a timed symptom log of everything experienced throughout the test. My staff also makes written observations of the patient during the test and frequently also does a short cognitive assessment (to check memory, attention, concentration, etc.) at each blood draw. These combined objective and subjective observations are kept in the medical record and are reviewed and discussed in detail at the follow-up appointment in conjunction with the lab results. This integration allows us to correlate the pattern of body changes with the actual fluctuations in blood glucose and insulin levels. It has been remarkable what has emerged from this approach, both in terms of hidden problems being properly identified, and in terms of helping someone learn how her body responds, what’s contributing to the sensations she experiences, and what to do to with eating plans designed to constructively correct the problem. Nine times out of ten, this process leads us to the insights needed to turn things around. It gives the person herself, and the nutritionist, important data to take into account in meal/snack planning. Once again, my approach is fairly basic in concept: observe the person, listen to what she says, pay attention to body physiology and hormonal effects, and figure out how to put it together into a cohesive, integrated, individualized plan of action.

When doing a GTT it is a simple matter to test for insulin resistance by checking insulin levels each time a glucose level is drawn. The GTT is more expensive when the insulin levels are added; yet, if the insulin resistance risk factors are there, I think it is important to do. Evaluating such an important risk factor in a systematic way, timed with the menstrual cycle, allows for early identification of women for whom this is blocking progress in weight loss and adding to the likelihood of developing diabetes and heart disease.

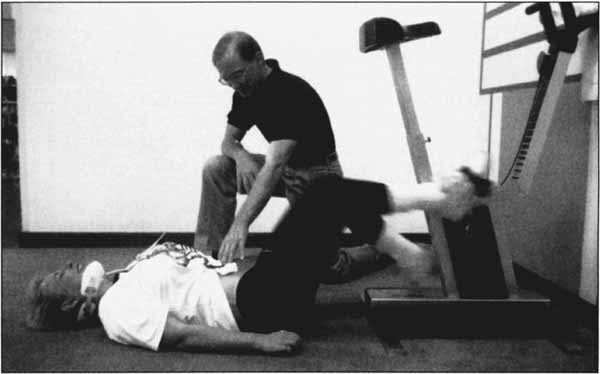

I have to be candid. There really are very few people who are so physically limited that they cannot exercise at all. With creativity, and guidance from physical therapists or trained exercise specialists, I have been impressed that there’s exercise appropriate for almost everyone. All you have to do is look at the remarkable accomplishments of athletes in wheelchairs to know that we can find some way to exercise the body. Even when I was in a neck brace and could only walk about ten yards, the physical therapist gave me two ways of exercising aerobically to begin regaining my strength and stamina. Take a look at the picture. You don’t have to sit on the seat to pedal a bike!

I have to admit, I made a pretty ridiculous sight, but it worked! The other exercise my physical therapist suggested was treading water, and I wore my neck brace in the water. Listening to music helped to stave off the boredom and keep up the pace. When I started out, I didn’t have the stamina to last more than a few minutes. By the third week, I had progressed to treading water for forty-five minutes, and I had made great gains in my leg, back, and arm strength. This experience was humbling, since I had been such a strong swimmer in the past. But what a sense of accomplishment after I had built up my endurance! I continue to enjoy swimming and water exercise. I have to admit that it’s easy to let my schedule demands keep me from getting in the pool as often as I know is healthy for me, but I am much better about keeping up the exercise because it helps me in so many ways. Each of us needs to find ways to increase body movement in all of our daily activities, particularly if the “exercise workouts” may be only three times a week.

I sincerely feel that if you have never exercised regularly in your life, there is nothing better you can do for yourself than sticking with a regular exercise program to boost your self-esteem and pride in accomplishment. Plus, you get to see the wonderful progress in your body once you start moving and keep at it. In addition to making you feel good about yourself, exercise, even simple walking, is the one wellness activity you can do that has so many profound effects on your total brain-body health and can prevent so many chronic, debilitating conditions and diseases. I have learned a great deal about the role of exercise in health through my own back surgeries and rehabilitation. I am grateful to have the strength and movement back that I have regained through exercise as a major part of each recovery process . . . even if I still miss the exhilaration of roller-blading! You may also find it worthwhile and very helpful at the beginning to hire a personal trainer to get you started and keep you on the right track until your new exercise habits are well established and you know how to do the exercises properly.

Begin now. Go for it!