Mister Robert Roberts Hitt, the well-known steno man, arrived in Springfield late on the sweltering afternoon of August 28, 1859. As he stepped down onto the platform of the new station, he paused briefly and nattily patted the beads of sweat from his forehead, then vainly attempted to tug the wrinkles out of his jacket. The Alton Express had covered the two hundred miles from Chicago in a quite acceptable nine hours. Hitt had tried with limited success to practice his shorthand on the ever-shaking rails. It had not surprised young Hitt that the carriage was far more crowded than he had previously experienced: the Peachy Quinn Harrison murder trial had attracted considerably more attention than might otherwise have been expected once it became known that Abe Lincoln was going to defend the accused killer.

A fair number of people were coming to Springfield to take the measure of Abraham Lincoln. His seven debates with incumbent senator Stephen Douglas the previous fall had gained him a national reputation, and the bigwigs were predicting he was going to make a run for the presidency in 1860. There was great interest in the man, and all the regional newspapers were covering the trial, including the Chicago Press and Tribune. The country had been introduced to him, thus far liked what it saw, and his conduct during the murder trial might help determine if this early flirtation would turn into a serious courtship.

Hitt already knew the cut of the man. Although he dismissed it humbly when offered credit, it was his fine work that had helped bring Lincoln into prominence. As a student at the Rock River Seminary and DePauw University, Bob Hitt had taken a keen interest in phonography, the skill of rapidly converting spoken words to print, and became quite an expert at this form of shorthand. It was a well-paying trade, and he opened his own office in Chicago in 1856, working regularly for the state legislature, the courts and on occasion newspapers, which were rapidly adopting this new form of journalism. He had first met Abe Lincoln in ’57, when he had been hired by the Chicago Daily Press to cover the Effie Afton trial, a landmark case that was to determine the balance between traditional river navigation rights and the construction of railroad bridges over a waterway. During that trial Lincoln had taken a liking to the energetic young reporter.

The great stir created when Lincoln and Douglas announced they would debate the complex moral, legal and economic issues of slavery and state’s rights throughout Illinois caused Press and Tribune co-owner and managing editor Joseph Medill to hire Hitt to bring a word-for-word account of the debates to his readers. Hitt’s transcriptions caused quite a stir. As newsman Horace White recalled, “Verbatim reporting was a new feature in the journalism in Chicago, and Mr. Hitt was the pioneer thereof. The publication of Senator Douglas’ opening speech in that campaign, delivered on the evening of July 9, by the Tribune the next morning, was a feat hitherto unexampled in the West.”

Hitt’s transcriptions were sent by telegraph to newspapers throughout the entire country, including Horace Greeley’s important New York Tribune, and in several weeks transformed a little-known Illinois lawyer into a widely admired politicial figure.

Lincoln was so taken with these transcripts that he requested two copies from the Press and Tribune’s co-owner Charles H. Ray, offering to pay “for the papers and for your trouble. I wish the two sets, in order to lay one away in the raw, and to put the other in a Scrap-book.” That “Scrap-book,” as he referred to it, was eventually published and sold more than thirty thousand copies, which added to his luster.

Lincoln spoke plainly and forcefully, the power of his words defining his character for many thousands of Americans; but he also was shrewd enough to appreciate Hitt’s value to his ambitions. So much so that at the second debate, in Freeport, Lincoln was dismayed when Hitt was not present onstage and refused to begin until the steno man could be lifted out of the throng and seated on the platform, his papers on his lap.

The two men, the tall, angular Lincoln and the small and slender Hitt, had become good friends, and were brought together again at this murder trial. Lincoln had already agreed to defend Harrison when Hitt was hired by the Illinois State Journal to provide a daily transcript for its readers. But as the trial began both the families of the accused, Quinn Harrison, and the victim, Greek Crafton, purchased copies of that transcript, which would prove a valuable tool should an appeal be necessary, paying $25 each. Lincoln subscribed for an additional copy from his friend Hitt, for which he paid $27.50. Hitt also was permitted to provide copies of his transcript to newspapers. If that recording might also prove beneficial in spreading Lincoln’s reputation, well, certainly none of his admirers would find that objectionable.

Hitt was quite pleased to accept this opportunity. In addition to his substantial fees, the attention given to the trial would also boost his own growing reputation as a pioneer in the field. Trial transcriptions were still extremely rare. There existed no devices to assist the reporter, meaning every word had to be captured by hand, an extraordinarily time-consuming and difficult process. Especially in a courtroom where complicated legal terms and phrases were proudly bandied about. And, in most instances, there didn’t seem to be much need for every word to be written down. Judges didn’t rely on transcripts to make their decisions. Summaries of the proceedings had long been sufficient. And when necessary lawyers were expected to be truthful in their memories.

Like most early practitioners of this profession, Hitt had developed his own system. Although relying mostly on the phonemic orthography method introduced in 1837 by the Englishman Sir Isaac Pitman, in which symbols represented sounds that could later be transformed into words, he had added those flourishes necessary for American English. He usually made his own transcriptions from those notes, but when pressed for time his assistant, a French Canadian named Laramie, would assist him with them.

In addition to a change of clothing, Hitt carried in his carpetbag the necessary tools of his trade: several of the new Esterbrook pens with long-lasting steel nibs, a supply of ink and a sufficient number of loose sheets of machine-produced paper. While the potential benefits to Lincoln’s political future that could be gained by providing an exact transcript to the Chicago newspapers—and beyond—were obvious, there also was an element of risk: Lincoln’s reputation was relatively untarnished; he had won the popular vote in the Senate election of ’58, but at that time senators were appointed by state legislatures, and the Democratic majority in the Illinois legislature had awarded the seat to the Democrat Douglas. Should he lose the trial, should he even make a major misstep, should Peachy Harrison be convicted of murder, the spotlight now focused so brightly on him might be dimmed. Creating an aura of invincibility is the goal of every person who stands for election, and a loss in the courtroom might easily damage that perception.

* * *

As Hitt walked purposefully from the station to Lincoln’s office on the west side of the public square, he noted with satisfaction how rapidly Springfield was growing. Only two decades earlier, when Lincoln had arrived there to pursue his legal career, it had been barely larger than a village. It had been settled in 1819, with thick woods to the north and a vast prairie on its south. Slightly more than a thousand residents lived mostly in small-frame houses and cabins, and farm animals roamed freely on the black mud streets. The pigs, especially, lent an unmistakable aroma that seemed to have been built into the foundations. There were no pavements or sidewalks, and large chunks of wood had been laid down to ease crossing the streets, which were, according to Lincoln’s biographers Nicolay and Hay, “of an unfathomable depth in time of thaw.” But even then, as Lincoln had written in a letter to a friend, it was “a town with some pretentions to elegance.” It was a place with a spirit. Even in those early days Springfield was a town that rewarded enterprise, a perfect spot to settle for a bright young man with passion. Lincoln eventually fit in well there. As a member of the state legislature in 1837, by dint of his “practical common sense (and) his thorough knowledge of human nature,” wrote fellow state official Robert L. Wilson, he had been instrumental in convincing his reluctant colleagues to transfer the state capital there from Vandalia.

The first railroad line in Springfield opened in 1842, though it was not permanent until a decade later. By 1856, when this photo of the railway station was taken, the Iron Horse had brought the world to Springfield, knitting it to the wonders of Chicago and beyond.

Abraham Lincoln Presidential Library and Museum

Progress had come to Springfield slowly, but steadily. By the early 1850s the nearly six thousand residents of this “prairie Philadelphia” were connected to the world by telegraph, the railroad and several newspapers. Impressive carriages had become common sights on the newly paved streets. The bankers had come to town, bringing with them all the necessary and desirable services and trades. Shops carried fashionable items brought from New York, Boston, St. Louis and Philadelphia. It was a prosperous city now, and politicians from the various parties, among them Douglas Democrats, Fillmore Americans and the newly formed Republicans, converged there to plot party strategy, do state business and perhaps cut themselves a slice of the public pie.

And people who needed to know were aware that there was at least one active station on the underground railroad carrying escaped slaves to freedom. Although no one dared talk about it in public, Lincoln’s neighbor, a free black man named Jameson Jenkins, a teamster who lived only five doors away from the Lincoln family, was believed to be the primary conductor.

It was a fine place to be a businessman, a working man or a lawyer; especially a lawyer. As the seat of the Sangamon County circuit and the home of the state supreme court, at times it seemed to be overflowing with lawyers. Lincoln had started his career there by borrowing a horse and riding what was known as circuits, sleeping two lawyers to a bed in a tavern and killing a chicken for his dinner, but time and effort had made him among the most respected members of the local bar. Springfield was a bustling city, but not yet large enough to support all the lawyers practicing there. In 1839 the Eighth Judicial Circuit was formed, consisting of numerous contiguous counties too small to maintain a regular court presence. It grew to include fourteen counties covering ten thousand square miles. Like a traveling show or even a circus, twice a year a caravan including a judge and a pack of lawyers would bring the law to each county seat, setting up court for a period ranging from a few days to two weeks. As soon as they settled in, they would be approached by people in need of their services and to strike deals. Sometimes they would conduct the trial themselves, but equally often they would be hired to assist a local practitioner.

Like most attorneys of that period, Lincoln had no specialty; he dealt with both civil and criminal cases. When called upon he would sit as a judge, act for the community as a prosecutor or represent individuals with a gripe, a claim, a need or a criminal charge. He might just as easily be found settling a minor land claim as arguing an historically important case to determine navigation rights on America’s rivers; on the same day he might write a will in the morning and defend an accused rapist in the afternoon.

While certainly it lacked the sparkle of Chicago, Hitt found Springfield to be a pleasant city where a visitor could easily find a clean place to stay, a satisfying meal and whatever entertainments were of interest.

The law office of Lincoln and his younger partner, William Herndon, was in a back room on the second floor of a brick building on the northwest side of the square, on Fifth Street. It faced the courthouse square. A small signboard on the street reading Lincoln & Herndon directed potential clients to the narrow stairway. Hitt knew Lincoln to be a man who carried most of what he needed in his mind, although when necessary he actually carried his legal papers in his tall hat, and spent as little time as possible on the mundane chores that chewed up the day. So Hitt was not at all surprised when he walked into the clutter.

It would be charitable to describe Lincoln’s office as messy. It was well beyond that, well beyond anything that might be fixed by a regular cleaning. Or two. A pair of windows overlooking the backyard were caked so thickly with dirt and grime that very little light edged into the room, which actually was a sort of blessing, as the dim light obscured much of the disorder. One of the many young men who did their legal training there claimed to have found plants from a forgotten bag of bean sprouts growing in a pile of dirt in a corner. A large ink blotch stained one wall, supposedly the result of an angry law student firing an inkstand at another young man’s head. One visiting attorney, Henry Whitney, wrote flatly, “no lawyer’s office could have been more unkempt, untidy and uninviting than that of Lincoln and Herndon.”

A long table ran lengthwise down the middle of the room, crossed at the far end by a smaller table to form a T. Both tables were covered with a faded green baize and numerous piles of papers and law books. Other piles were scattered on the floor around the office. On a stack of papers tied together with a string Lincoln had written boldly, “When you can’t find it anywhere else, look in this.”

The afternoon had begun cooling into the early evening, but Hitt was not at all surprised to find Lincoln still at work; it was well-known that he found Mrs. Lincoln to be difficult, and he often found peace in his office. Besides, with the Harrison trial about to begin there was considerable preparation to be done. As Hitt entered the office, he heard Lincoln reading out loud from his notes, as was his practice, then saw him stretched out full-length on two hard chairs, his eyes fixed on the pages.

“Mr. Hitt,” Lincoln greeted him, straightening up. “Thank you for coming.”

“Mr. Lincoln,” Hitt responded. “And thank you for arranging it.” Hitt cleared another pile of books from a chair and sat down. The two men exchanged pleasantries. While Lincoln seemed to be as naturally engaged as in their previous meetings, Hitt was surprised to feel a distance between them, as if he were seeing an old friend through new eyes. Odd, he realized, all the hoopla around Lincoln appeared to have affected him to a far greater degree than it had the man himself. He realized with a start that he was responding more to the created image than the flesh and blood person. But there was nothing to be done about it; the public had its hooks into him.

Lincoln did not pretend to be unaware of his changed circumstances; he had been pursuing public office for two decades, and his efforts were finally coming into bloom. It was what it was, and there was no reason now to ignore that reality. He was receiving numerous requests to speak at political gatherings around the country, even as far away as New York City, but most of them he had turned down.

What daylight that somehow had managed to seep through the windows gradually disappeared. Lincoln lit two candles and began telling stories. This was the man his companions knew well, a man always ready with a story, often told at his own expense. Hitt had heard it said that no one knew the real Abraham Lincoln—he kept much of what motivated him safely boxed inside—but everybody knew his stories. They were almost legendary, and those he didn’t repeat personally others did for him. Everybody who knew Lincoln had heard him explain that while he had served in the Black Hawk War, “If (General Cass) saw any live fighting Indians it was more than I did; but I had a good many bloody struggles with the mosquitoes...”

His ability to capture a room with some soft-spoken words had served him well, whether sitting around the evening fire in the back of his friend Joshua Speed’s general store or transfixing a crowded courtroom. Hitt had asked him about the state of his practice, which after several turns led him to a story about a recent murder case that had raised some questions. As he told it, after suffering through half a century of a bad marriage, seventy-year-old Melissa Goings had finally reached her limit. When her seventy-seven-year-old husband, by all accounts an irascible old codger, had tried to choke her, she took hold of a solid piece of stove wood and hit him twice, fracturing his skull and killing him.

The old man wasn’t much missed, but the law had little sympathy for his widow. Lincoln’s face glowed in the flickering candlelight as he continued his tale. The widow Goings was indicted and charged with her husband’s murder, he continued, and some sympathetic townsfolk hired him to defend her. The facts were not in her favor, and the judge was known to be tough. On the morning her trial was to begin, Lincoln received permission from the court to consult privately with his client on the ground floor of the courthouse. “I reckon I did just that,” he told Hitt. But later, when the bailiff came to get her, Melissa Goings could not be found. Asked by the judge where she had gone, Lincoln recalled, he had shaken his head and replied, “Don’t know, your honor. I left her on the lower floor. She should be in the care of the sheriff.”

Well, Lincoln continued, Melissa Goings apparently was gone, never to be seen again. “The bailiff, Mr. Robert Cassell, was plenty upset with me. He said strongly, ‘Confound you, Abe, you have run her off.’

“‘Oh no, Bob,’ I said to the man, ‘I did not run her off. She just wanted to know where she could get a good drink of water—’” here he paused for the maximum effect “‘—and I told her there was mighty good water in Tennessee!’” There was a sprightly joy in his voice as he delivered his final line, as if he were loudly sharing a secret known by everyone in the world. It would be rumored later that he had gone so far as to open the window for her, and helped her climb out of it, but that was never proved; in fact, there were never any claims of wrongdoing of any kind. The case was dropped. While clearly Lincoln had stretched the limits of the law, it was just as clear that he believed justice had been served, if not quite done.

Hitt was worn from his long trip, and hungry, and he hadn’t yet put his bag down in the rooming house, but there was time for all that. He was not about to give up these relaxing minutes with Lincoln. And, as he expected, eventually Lincoln came around to telling him about the case at hand.

Hitt knew the general facts—the newspapers had been writing about them—but Lincoln added the color. Seven weeks earlier, on Saturday the sixteenth of July, Greek Crafton had walked into the Short and Hart’s drugstore in Pleasant Plains, Illinois, about ten miles outside Springfield, carrying with him a ton of anger. His older brother John Crafton was stretched out on a counter; his reason for waiting there was still in dispute. Simeon Quinn Harrison, “Peachy” as he was called, was sitting at the other counter next to Mr. Short, reading the newspaper. Harrison was a frail young man, weighing no more than 125 pounds, and Greek had a substantial advantage of size over him. Greek took off his coat, and with his brother grabbed hold of Harrison and pulled him away from the counter. According to Lincoln, the Crafton brothers tried to drag Harrison into the back of the store to administer a sorrowful thrashing. Proprietor Benjamin Short tried to step between the boys but was pushed away by brother John.

The smaller Harrison struggled to break free. Greek Crafton struck him a hard blow. The brawlers fell over a pile of boxes. With that, Harrison pulled a four-inch-long white-handled hunting knife and began slashing at his tormentors. Stabbing wildly, he made a deep slice into Greek’s stomach. As Greek stumbled away, Harrison stabbed at John, catching him on his wrist and opening a nasty cut. To keep Harrison away, John threw a balance scale, some glasses and even a chair at him before they finally could be separated.

But Greek had been grievously wounded, cut from the lower rib on his left side to his groin on the right. Crafton’s bowels protruded and later were pushed back into place by Dr. J. L. Million. He was taken to bed and lingered for three days, but there never was any real hope of survival. Supposedly, on his deathbed, as Greek prepared to meet his Maker, he wanted to set himself right. Peachy’s own grandfather, the renowned Reverend Peter Cartwright, had gone to pray with Greek, and was stunned when Greek said to him, “I brought it upon myself and I forgive Quinn, and I want it said to all my friends that I have no enmity in my heart against any man. If I die I want it declared to all that I died in peace with God and all mankind.” But a statement of forgiveness wouldn’t change the law.

Quinn was arrested and his family hired the men who would defend him.

The event inflamed local passions. Everybody in the area knew the boys, Quinn Harrison and Greek Crafton, and held an opinion about them. “There is much excitement manifested among the friends of the respective parties,” the Daily Illinois State Journal reported. Pleasant Plains was a small village, and to some degree each of its seven hundred residents had a stake in the outcome. Anger took hold. Loud accusations and countercharges were made as supporters of both the accused and the victim rallied behind their chosen side. The local newspapers reported the facts—but also took the position certain to appeal to their readers. “We are informed that the Grand Jury have found a bill against young Quinn Harrison for the murder of Greek Crafton,” wrote the Journal. “By what mode of precedence they made up their minds to such an indictment is a mystery. If there ever was a case of killing in self-defense, we think the testimony at the preliminary examination of Harrison showed one.”

The rival Illinois State Register claimed the ethical position, declaring, “Whether rightly or not, it is not for the public press now to express an opinion, in justice to either party... The Journal’s paragraph is one which cannot but be depreciated by every thinking man. It is unjust to the party it assumes to defend, who, if not indictable for murder, cannot be benefited by mingling his cause with the partisan commentary of the newspaper press...we protest against the conduct of a public journal which assumes to prejudge judicial investigation...”

But there was far more to the story, Lincoln continued, creating a fuller picture of this sad affair for Hitt. The village of Pleasant Plains was close enough to Springfield to almost catch its shadow; on a dry day it was an easy ride from there into the city. Lincoln had known both young men for a considerable time, he told Hitt. Both of them came from wealthy and well-positioned farming families in the community. Peyton Harrison, the accused killer’s father, was a staunch Republican and a longtime friend and Lincoln supporter. The victim, Greek Crafton, also was close to him. In fact, he had aspired to the law and did much of his training as a clerk right there in the office of Lincoln & Herndon, acquitting himself quite well. To complicate matters even further, Lincoln had a long and mostly contentious relationship with Harrison’s grandfather, the Reverend Cartwright, who had recounted Greek’s deathbed comments. Peter Cartwright was an illustrious prairie preacher, famed for bringing the Methodist doctrine to the frontier—whatever it took. Once, supposedly, that required brawling with the legendary riverman Mike Fink. Like Lincoln, Cartwright’s power was in his words, and it was said his booming voice could “make women weep and strong men tremble.”

People said about Cartwright that “When he thought he was right no earthly power could persuade (him) to abandon a principle,” while adding that he always thought that he was right. There was no pretense between Lincoln and Cartwright; the two men did not take kindly to one another. Twice Lincoln had gone up against him for election. In 1832, in Lincoln’s first attempt to win public office, the good Reverend Cartwright had defeated him for a seat in the Illinois state legislature. They met a second time in the congressional election of 1846, an especially nasty campaign. Running as a Whig, Lincoln objected strongly to Cartwright’s insistence on bringing his religion into the public square. The Democrat Cartwright responded by tarring Lincoln as “an infidel,” a man unfit to represent good Christians. Lincoln had won that election, and neither of the men had seen fit to apologize.

The two men were preparing to meet once again, but this time in a courtroom, this time on the same side, this time with a young man’s life in balance. The trial might well turn on Cartwright’s recitation of Greek Crafton’s dying words—no juror with a heart could hear those words and not be affected—but getting them to be heard was the problem. Lincoln had to convince the judge to allow this hearsay evidence to be admitted. That was tricky territory. Hearsay is a statement made outside the courtroom by someone other than the witness. The witness, under oath, repeats what he was told or heard. When it is intended to prove the truth of the comment, it’s generally not permitted in a courtroom because the opposing side cannot question the person who made that statement. But in certain specific circumstances it is, and was, allowed.

Lincoln had tried more than two thousand cases, both civil and criminal, and in many of them he had known at least one of the participants, sometimes both. But he couldn’t recall a single one of them that was so entwined by personal complexities: he was charged with defending the accused killer of a young man he had admired, and in doing so he would be allied with a man with whom he had been at odds for decades.

Turns out, the incident had been sparked at least two weeks before the fatal confrontation, while the village celebrated the Fourth of July. Harrison and Crafton had known each other for many years, both had grown up in the village, for a time they had even been friends, but no one could state with certainty the precise cause of the bitterness between them. There was some talk that it concerned some difficulty over a Harrison woman. Greek’s brother William had married Peachy Harrison’s sister Elizabeth Catherine and there were rumors about abusive behavior, which may well have played a role. At the town picnic on the banks of the Sangamon River, Peachy Harrison had warned his younger brother Peter that he best stay away from the Crafton family, disparaging them as “not fit associates.” Others claimed that Harrison had slapped Crafton, but there was not a lot of support for that. Whether Harrison did or did not lay a hand on him, Greek took umbrage at the insults making their way through the local rumor mill and challenged the smaller Harrison to a fight. It had become a matter of honor. Friends stepped between them before the situation burst out of control, but Crafton was not satisfied. Witnesses heard him threaten to whip Harrison the next time he saw him, to which Peachy warned that if Greek ever dared lay a hand on him he would defend himself—with a gun!

Lincoln paused here and shook his head sadly at the folly, knowing this waste of a good life might so easily have been avoided at so many points if only some cooler head had stepped between them...

Hitt listened silently in the flickering candlelight, recalling a story he had heard only months before, about how Lincoln himself had responded years earlier when finding himself in a somewhat similar position. In that situation, as in this one, honor had been at stake. It was impossible to know how much of the story was true and how much was shine for political purposes, but certainly there was some truth to it. During a dispute over banking policy in 1842, Lincoln and Mary Todd had written anonymous letters to the local newspaper ridiculing her former fiancé, Illinois state auditor James Shields. They called him “A fool as well as a liar.” When Shields learned the authors’ identities, he demanded a retraction, and when it was refused, he challenged Lincoln to a duel. They met at a place called Bloody Island, but rather than pistols Lincoln declared they would fight with large cavalry broadswords. Supposedly the much taller Lincoln intimidated his rival by slicing an overhanging branch from a tree with a single blow, causing Shields to agree to an offered truce, his honor intact. Although an alternative ending claimed mutual friends had interceded to prevent bloodshed. Whatever the actual resolution, the foolishness had been stopped without injury. But not in this case. Rather than simmering, Lincoln said, the dispute began to boil. Fearing Greek Crafton, Harrison borrowed a knife and carried it with him always. During the next few weeks, additional insults were exchanged and the threats escalated, until the fateful morning of the sixteenth.

* * *

Greek Crafton had lingered for three days before succumbing to his injuries. For a time it was also feared that his brother John, whose wrist was sliced open, might also die. He survived. Then, for almost a week following the deadly encounter, Peachy Harrison could not be found. In fact, as it became known later, he was in hiding, perhaps in fear of Greek Crafton’s posse of friends or supporters, perhaps to keep himself out of the sheriff’s hands until a proper defense could be arranged. For a time his good friend, the twenty-nine-year-old city attorney Shelby Moore Cullom, gave him cover in his home, then hid him under the floor of the Illinois State college building.

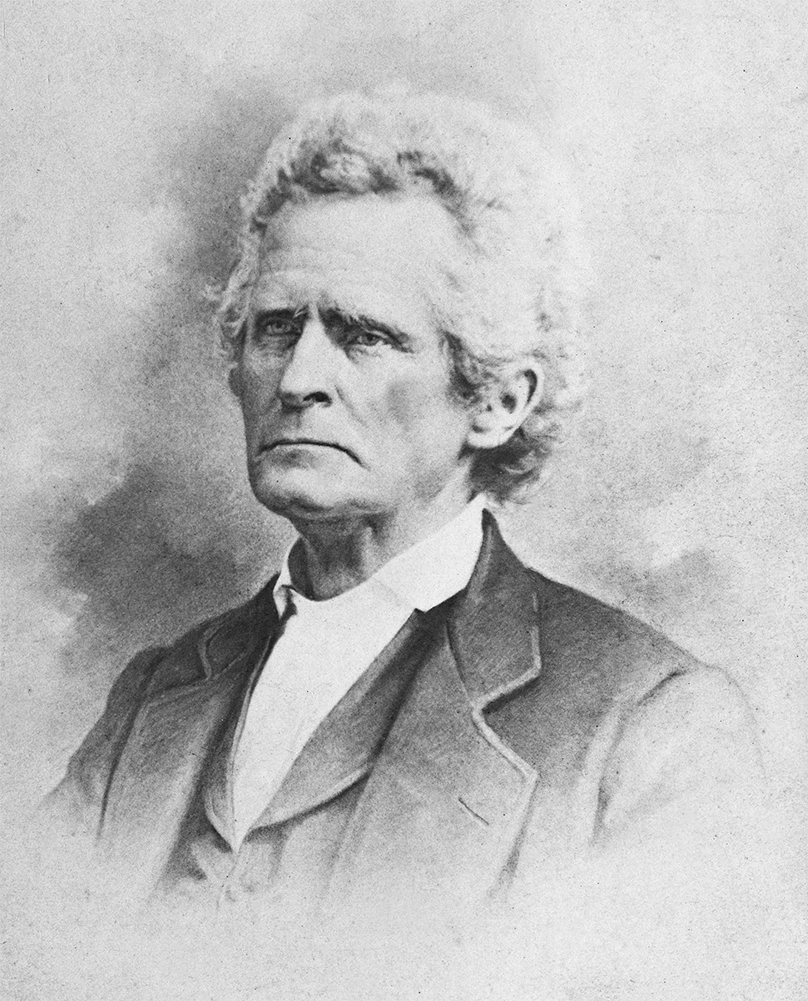

During his presidency Lincoln described Stephen Trigg Logan as “one of my most distinguished, and most highly valued friends.” The fact that Logan, perhaps the most respected lawyer in the region, had selected young Lincoln to be his law partner provided a tremendous boost to Lincoln’s career. One reason for the selection, he later wrote, was that Lincoln had the ability to bond with all people: “Lincoln seemed to put himself at once on an equality with everybody—never of course while they were outrageous, never while they were drunk or noisy or anything of the kind.” Logan was one of the few people the president invited to travel with him to Gettysburg for the dedication of that battlefield.

Abraham Lincoln Presidential Library and Museum

The boy’s father, Peyton Harrison, retained an eminent former judge, Stephen Trigg Logan, and Lincoln to represent his son. There were strong bonds between all of these men. Lincoln had first represented Peyton Harrison in a minor dispute more than two decades earlier, and they had remained friends since. The wealthy Harrison had been a key contributor to Lincoln’s political ambitions. Judge Logan had been a mentor to Lincoln, as well as a friend. In 1841 Logan had offered a partnership to Lincoln. It had been dissolved after three years because Logan wanted to work with his son, and by then Lincoln felt ready to establish his own firm. The partnership had been an amiable and productive relationship, and Lincoln always spoke fondly of the man and all he had learned from him. They separated quite amicably, and both men had continued to grow in stature through the years. Few lawyers in the area were more respected than Logan and Lincoln, Hitt knew, and Quinn Harrison could not have better representation. If my fate was to be decided in a courtroom, Hitt thought, these are the men I would choose to defend me.

Lincoln’s current partner, Billy Herndon, himself a fine attorney, was added to the defense. And finally they accepted Harrison’s suggestion that his friend Shelby Moore Cullom assist them. “My duties,” Cullom later remembered, “were looking up authorities and testimony and generally doing the common work of the concern.”

The coroner’s inquest into the facts of the encounter, to determine if a crime had been committed, had convened on August 2. The legal question here was simply whether Greek’s death should be deemed a homicide rather than some other noncriminal cause of death. Because of his prior work with Lincoln, Hitt had followed the events as much as possible in these earliest stages, although the details had been sketchy. The courtroom had been densely crowded but still the spectators exhibited fine behavior throughout the two-day hearing. As many as seventy-five witnesses were subpoenaed, and most of them eventually testified. “Listen to this, Bob,” Lincoln said, withdrawing a newspaper from the pile he had been reading. “Here is the crux of the matter. This from the Register, ‘In the most debatable testimony, Mr. Cartwright testified that Crafton, on his deathbed, absolved Harrison from blame, and blamed himself for the difficulty and its sad result... This was rebutted by Dr. Million, who stated that he had several conversations with Crafton on his dying bed, relative to the difficulty, and that he did not absolve Harrison from blame, but censured him.’” He laid down the newspaper, squeezed the bridge of his nose between his thumb and forefinger, and continued. Hitt forced himself to hide a yawn, the heat and the long trip finally taking a toll.

Lincoln explained that he and Logan had agreed immediately on their strategy for this hearing: this was clearly a case of self-defense. Peachy Quinn had been attacked by the Crafton brothers and had been forced to fight back to save himself. One witness even testified that he had heard Crafton boasting that he intended to throw down Harrison and stomp on his face.

The prosecution disagreed, of course, examining the same facts and arguing quite a different conclusion: the laws concerning self-defense had been mostly settled; a man had no legal right to stand his ground but to save himself from imminent and serious bodily harm or death—then and only then did he have the right to use deadly force. Harrison could have avoided this fight, but instead had armed himself with a deadly weapon that he was prepared to use. When given the opportunity, the prosecution argued, he had knowingly murdered Greek Crafton.

The whole of the event was argued back and forth with great skill, although Lincoln admitted to Hitt that neither he nor Logan anticipated it would end at the initial pretrial hearings. Feelings were far too raw for a decision to be reached without all of the evidence being presented and all of the witnesses heard. Failing that, the town might never heal. There would have to be a full-blown trial.

The coroner’s inquest came a few weeks before the Sangamon circuit Grand Jury would officially determine if charges were to be lodged against Harrison.

That was but a formality, Lincoln knew. The Grand Jury would indict and Peachy Quinn Harrison’s trial would begin within days after that. “That’s the sum of it,” Lincoln said finally. He then offered to escort Hitt to the Globe Tavern, the boardinghouse where he would be lodging during the proceedings. Mr. Harrison had arranged these accommodations, Lincoln told him, and he was confident the stenographer would be quite comfortable there. “I know the place well,” he said. “My own family lived there for a time.” It was, in fact, the first home he shared with Mary Todd; they had paid $8 a month to live there through the first year of their marriage. In fact, it was there that their son Robert had been born.

Lincoln did not bother locking his office. It would have served no purpose, Hitt noted; the two lower panes of glass in the door were missing, and he saw no effort had been made to replace them. The two men strolled slowly through the gaslit streets, Lincoln nodding to passersby as they greeted him. The heat had subsided only slightly. As they walked into the night it occurred to Mr. Robert Roberts Hitt that Abe Lincoln, a man in his ascendancy, seemed in no hurry to get home.