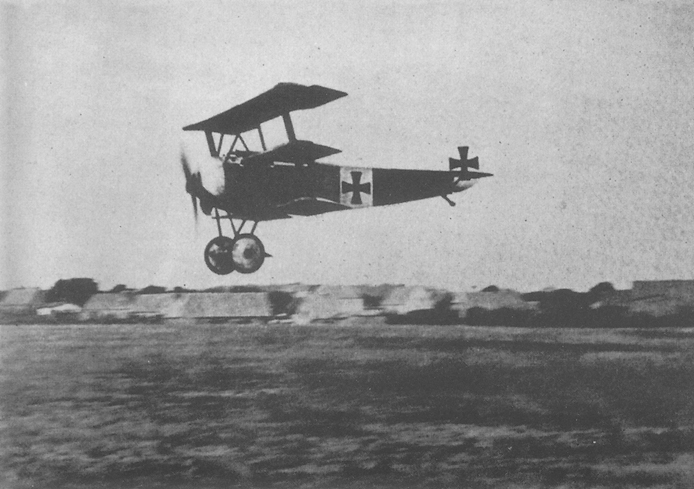

the Fokker Dr 1 triplane was used extensively during the later part of the First World War. This particular machine is being flown by fighter ace Manfred von Richthofen

THE Stout man in the immaculate braided uniform stared intently out across the English Channel. Almost at his feet, the grey cliffs of Cap Gris Nez fell steeply away to the sea, and above his head the gulls swept past with shrill cries. The breeze lightly touched his face, bringing with it the unfamiliar tang of the sea; the morning was fine but misty, and across the water he could just make out the faint white outline of the English coast.

Suddenly, Hermann Goering raised the powerful naval binoculars in his hands, gazing up at the myriad gleaming dots—the vast formations of his fighters and bombers known as Valhallas—that had appeared almost overhead. The sky echoed with the thunder of mighty engines as Geschwader after Geschwader swung majestically out over the sea, a great aerial armada such as this man who watched had always dreamed of sending against London. “My bombers will darken the skies over England,” he had once said, and now, his eyes on the resounding heavens, he saw the fulfilment as his Luftwaffe went forth to war.

It was a historic moment, and he could not resist the supreme joy of sharing it with the German people. The medals and decorations he wore gleaming brightly in the sunshine, he grasped the microphone before him and poured words excitedly into it, shouting that a great air assault was taking place on London, and that he, the architect of German air power, was listening to the roar of his bombers as they crossed the English Channel. The group of officers clustered around him looked at each other and listened in silence to the rambling, emotional outburst; they knew that Goering could be forceful and ruthless when he was in the mood, but only too often he embarrassed them by acting like a child.

Over 300 German bombers and 600 fighters, stepped up in solid layers of aircraft, took part in this first mass raid on London on 7th September, 1940, attacking in two waves at heights between 16,000 and 20,000 ft. Sheer weight of numbers carried the Luftwaffe formations through the aggressive, harrying Spitfires and Hurricanes of four Fighter Command squadrons and over the capital, where they dropped their bombs. Despite fighters and anti-aircraft fire the targets were hit, and hit hard. The dock area became a blazing inferno, the oil tanks at Thameshaven were set alight and dozens of houses in the East End destroyed, while more and more R.A.F. fighter squadrons rose into the air to tangle with the masses of enemy aircraft, until almost the whole of 11 Group had been committed. Poplar, Woolwich, Limehouse, Tottenham, Barking and Croydon, all were deluged with bombs before the German forces turned back, losing forty aircraft at a cost of twenty-eight R.A.F. fighters.

When darkness fell, the vast London docks were still blazing furiously, and the great beacon of fire drew a further heavy raid by over 250 bombers, which lasted until the following morning, 13,000 incendiaries lighting so many conflagrations that the sky glowed dully for miles around with the reflection. Goering was not quite correct when he reported gleefully, “London is in flames,” but he could hardly be blamed for assuming the destruction of the city to be complete, with so many fires out of control. In fact, the martyrdom of London was just beginning, and would continue without respite for another fifty-nine endless nights, yet the British people, like the R.A.F., could “take it” and somehow managed to emerge battered but undefeated from the smoke and rubble each morning.

On 8th September Fighter Command put eleven squadrons into the air in good time to intercept and repulse the main daylight raid by about 100 bombers against the Kent and Essex airfields, but during the night Luftflotte 3 again successfully bombed London, causing many fires, including twelve conflagrations, and rendering every southward railway line out of the city unserviceable. The following afternoon, 11 Group again broke up the enemy formations before they reached London, and most of the raiders jettisoned their bombs in confusion. Twenty-eight German aircraft were shot down during the day for the loss of nineteen R.A.F. fighters. The same night over a hundred enemy bombers attacked London almost from dusk to dawn, heavily damaging many residential areas and causing over 1,700 casualties, their repeated successes and negligible losses indicating only too well that the capital still lacked efficient night-fighter and anti-aircraft defences.

Unsettled weather brought a welcome lull in the offensive during the next three days, although on 13th September single enemy aircraft penetrated to central London and dropped bombs on Downing Street, Whitehall and Buckingham Palace. Nevertheless, thousands of invasion barges were massed in the ports along the coast of France, and the slackening in the air assault obviously amounted to nothing more than a calm before the storm. “If this invasion is to be tried at all, it does not seem it can be long delayed…” Winston Churchill warned the people of Britain. “Therefore we must regard the next week or so as a very important period in our history. It ranks with the days when the Spanish Armada was approaching the Channel … or when Nelson stood between us and Napoleon’s Grand Army at Boulogne….”

At a conference in Berlin on 14th September Hitler informed his field marshals that all naval preparations for the invasion had now been completed, and added that, in his opinion, four or five days of good weather would be sufficient for the Luftwaffe to achieve complete air superiority, and 17th September would therefore be the final date for Sealion. While he was speaking, three formations of German bombers and fighters were striking at London and battling furiously with no less than twenty-seven R.A.F. fighter squadrons, fourteen aircraft of each side being shot down. The Luftwaffe and Fighter Command were now suffering almost proportional losses every day, and the German air staff felt that the British air defence system had been weakened to such an extent that it was on the point of collapse; one knock-out blow should be enough to overwhelm it. Uncomfortably aware that his “lightning offensive” against England had now dragged on for nearly three months, Goering willingly agreed with the latest appraisal of the situation, and ordered the final great air assault on London to take place the following day.

In anticipation of this major daylight attack, the night raids on 14th–15th September were on a greatly reduced scale, warning Fighter Command that a second, and even more fateful Adlertag was at hand. “I see only one sure way through now—to wit, that Hitler should attack this country, and in so doing break his air weapon,” Winston Churchill had said in June, on the eve of the Battle of Britain. That air weapon had since been bruised, bent and blunted; now, it remained only to be seen if the weary British defence organisation could muster sufficient strength to snap the blade thrusting at the heart of London. Though neither Goering or Dowding realised it at the time, this was the climax of the whole battle, reached at a moment when both sides were stretched to the limit; and all the military bands in Germany blaring out the inevitable “Wir fahren gegen England!” and newspapers in England loudly proclaiming great enemy losses made not the slightest difference. In the final outcome, the youth of Britain faced the youth of Germany in the air, and the courage, will power and determination—or lack of it—of these so alike and yet very different men would win the day.

On 15th September, 1940, the warm Sunday ever afterwards to be remembered annually as the greatest day of the Battle of Britain, opened with misty weather that quickly cleared and gave way to brilliant sunshine. During the morning Mr. and Mrs. Churchill visited the 11 Group underground operations room at Uxbridge, and by eleven o’clock the Prime Minister was listening to the reports of many enemy formations circling over their airfields in France. “Forty plus… sixty plus… eighty plus…” intoned the plotters, and still it went on, until the operations table became saturated with raids as hundreds of heavily escorted German bombers set course for England. As the great armada moved across the Channel, Air Marshal Park began to commit his waiting squadrons, and soon fierce air battles were raging over Kent, with the scattered German forces breaking away in all directions, dropping their bombs anywhere and everywhere. Soon, Park had ordered nearly the whole of his 11 Group into the air, and as more Do 17s and Ju 88s thundered in across the Channel the five squadrons of 12 group, built up into a massive wing formation, rose to engage them. Smoke and flame and gunfire mingled in an inferno of sound and fury, and soon aircraft were falling everywhere; a Do 17 in the station yard at Victoria; a Spitfire and another Do 17 locked together in tangled wreckage over Kent; and a Hurricane pilot who baled out ending his descent in a Chelsea dustbin. Then, suddenly, the shattered German formations were streaming back to the coast, utterly defeated by the combined efforts of 11 Group and the five squadrons of 12 Group—the famous Duxford wing.

In the operations room at 11 Group headquarters, the staff worked quickly and efficiently to land their squadrons for refuelling and rearming, keenly aware that at any moment another mass raid could explode in at low level from the Channel. “How many fighters have you left?” asked Mr. Churchill, meaning, of course, at instant readiness for just such an emergency. “None, sir,” replied Air Marshal Park; the whole of 11 Group, the breastplate of Fighter Command, lay naked and defenceless on the ground. Then slowly but surely the bulbs began to glow again on the totalisator as one squadron after another completed refuelling and rearming, and Churchill and Park—and England—could breathe again.

Two hours later, the second Luftwaffe assault came in from the sea in three waves, some hundred and fifty aircraft, with more on the way. They were intercepted at once by twenty-three squadrons from 11 Group and the five squadrons of the Duxford wing, and savage, running battles unreeled all over the sky on the way to London. Two of the enemy formations were broken up by the 11 Group fighters before they reached the capital, and the bombers that did manage to fight their way through were met and hammered mercilessly over the target by the Duxford wing. Again there came that desperate, whirling tumult of tracer, burning aircraft, sweating hands and thudding hearts, every second of time vivid with the brilliance of violent death, then another ten minutes snatched out of eternity were over and the German forces had scattered once more.

Thanks to the perfect teamwork and sheer determination of Fighter Command, the Luftwaffe had failed completely to repeat its success on 7th September over London, bombs being jettisoned over a wide area and causing comparatively little damage. Fifty-six German aircraft had been shot down, and the remainder were straggling back to their bases, some with cockpits running in blood and dead or wounded men lying among the empty ammunition drums and spent shell cases that littered their interiors, others with bullet-starred windscreens or smoking engines, all bearing the unmistakable signs of a savage battle. “Listen to the engine singing—get on to the foe! Listen, in your ears it’s ringing—get on to the foe!” had thundered the Luiftwaffe marching song against England, but to no avail. Disillusioned and bewildered, the German airmen were left to contemplate an apparently endless future battering away at a fighter force that had already been destroyed on paper, yet continued to rise like a phoenix from the ashes of defeat.

So ended what came to be known as the greatest day of the Battle of Britain, save for an unsuccessful raid by about twenty bomb-carrying Bf 110s of Kampfgruppe 210 on the Supermarine works at Woolston in the late afternoon. It has sometimes been said that a fighter-pilot is privileged to select his opponent and kill gracefully, with all the skill and artistry of a modem Lancelot, but such chivalrous combats were uncommonly rare on 15th September, 1940. Too many of the air battles that day were fought at high speeds and close quarters, with more than a hint about them of the axe and sword work of war in the Middle Ages, a bloody butchering business, with every man fighting for himself and devil take the hindmost. Some Fighter Command pilots attacked at such point-blank range that their victims literally exploded right in front of their windscreens, and they found themselves hurtling through the black smoke and flying wreckage. German bombers trying to retain a tight formation were knocked out of control by the concussion when one of their number blew up under fire, and men who baled out were fortunate to tumble unscathed through the confused mêlée of roaring, gun-flashing aircraft. At least one Hurricane pilot returned to base with blood spattered on his engine cowling and pieces of human flesh in his radiator, grim evidence that air fighting could not always remain cold and impersonal when eight Browning guns were used at close range. It had been a great and yet tragic day memorable not only as a victory, but because so many individual acts of courage and determination shone brightly through the ugliness of war.

Hermann Goering was in despair, a ridiculous, sweating figure in a now crumpled uniform, mopping the perspiration from his brow with a handkerchief as he listened to the gloomy reports of scattered formations, bullet-riddled aircraft and heavy casualties. Turning like a dog at bay on the weary fighter arm of the Luftwaffe he again accused his pilots of unwillingness to get at grips with the enemy, and ordered them to provide an even closer escort for the bombers. In future, he said, the mass formations, or Valhallas, would only be used on rare occasions, and maximum fighter escort would have to be provided at all times. London remained an important target, but it was obvious that both Luftflotten must again concentrate on the Fighter Command bases and aircraft production centres. Goering admitted that his airmen were tiring and that the offensive was “very exhausting”, yet he still refused to look facts squarely in the face and stated that the R.A.F. fighter force could be finished off “in four to five days”. Gaining confidence from the sound of his own voice, Goering added that the Luftwaffe could crush Britain unaided, without the benefit of a seaborne invasion; a statement unlikely to amuse Hitler, who had massed thousands of barges in the Channel ports, with two army groups patiently awaiting embarkation orders.

In fact, the Fuehrer no longer had any illusions about the immediate chances of success for Operation Sealion. Until 15th September he had been fairly satisfied with the air offensive, and at a conference with his Service advisers in Berlin on the 14th still had sufficient confidence in Goering to comment: “… the operations of the Luftwaffe are above all praise. Four or five days of good weather are required to achieve decisive results….” The following day, with its violent air battles and heavy German losses, completely changed Hitler’s attitude to the invasion. Autumn was at hand, and yet, in his own words: “… the prerequisite conditions for Operation Sealion (had) not yet been realised,” and the British fighter defence seemed revived and more aggressive than ever. Taking everything into consideration, Hitler decided that Sealion, if attempted at once, would be a very risky business.

On the afternoon of 17th September, the diarist of the German Naval Staff recorded the Fuehrer’s decision. “The enemy air force is by no means defeated; on the contrary it shows increasing activity…. The weather situation as a whole does not permit us to expect a period of calm…. For these reasons, the Fuehrer therefore decides to postpone Operation Sealion indefinitely….” However, the Naval Staff carefully pointed out that the postponement did not mean that Sealion had been abandoned. “The Fuehrer still wishes to be able to carry out a landing in England even in October,” recorded the diarist, “if the air war and the weather conditions develop favourably.” Goering was thus committed to the unenviable task of continuing the air offensive until further notice, regardless of casualties, and against an increasingly more powerful Fighter Command.

During the last fortnight in September the now smaller German bomber formations and their massive fighter escorts continued to hammer away with a weary indifference at the south-coast aerodromes and factories, and the air still trembled to the brittle chatter of machine-gun fire, but it soon became apparent that the immediate danger to England had been averted. It continued as a strange battle that seemed unending, and became history while it still raged and men died high up in the late summer skies. A Spitfire gutted by gunfire, inverted and burning; a Heinkel in a spin, one engine on fire, the rear gunner hanging half in and half out of his cupola; a Hurricane seeming to hang motionless in the air, shaken by the recoil of its wing-mounted Brownings; and, beyond, a Bf 109 quickly flicking wing over wing, out of control, trailing a ribbon of flame and that long, high-pitched whine that is the last cry of a dying aircraft—these were the brush strokes, the vivid details, that completed the great sprawling canvas of the Battle of Britain. And all for nothing; because the Luftwaffe had already been beaten, and was merely wasting itself away.

On 27th September, as if shaken by a sudden outburst of childish temper, Goering hurled a last major daylight assault against England. In the early morning, a wave of bomb carrying Bf 110s with a heavy single-seater fighter escort came in over Dungeness, were hammered mercilessly by Dowding’s waiting squadrons all the way to London, and finally retreated in confusion, scattering their bombs anywhere. They were immediately followed by two strong formations of Do 17s and Ju 88s, which were also broken up and dispersed by the Spitfires and Hurricanes of 11 Group; and later by a further 300 raiders that struggled manfully across Kent and were turned back, shot to pieces, within sight of London. The only success for the Luftwaffe during the whole day, and that a moderate one, was achieved at Bristol, where the survivors of some eighty bombers directed against that city managed to hit their targets. Fifty-five German aircraft had been shot down by nightfall for the loss of twenty-eight British fighters, a conclusive R.A.F. victory that prompted Winston Churchill to signal the Secretary of State for Air in characteristic words the following morning: “Pray congratulate the Fighter Command on the results of yesterday. The scale and intensity of the fighting and the heavy losses of the enemy … make 27th September rank with 15th September and 15th August, as the third great and victorious day of the Fighter Command during the course of the Battle of Britain.”

the Fokker Dr 1 triplane was used extensively during the later part of the First World War. This particular machine is being flown by fighter ace Manfred von Richthofen

a squadron of Albatros fighters lined up at Taulis in 1916

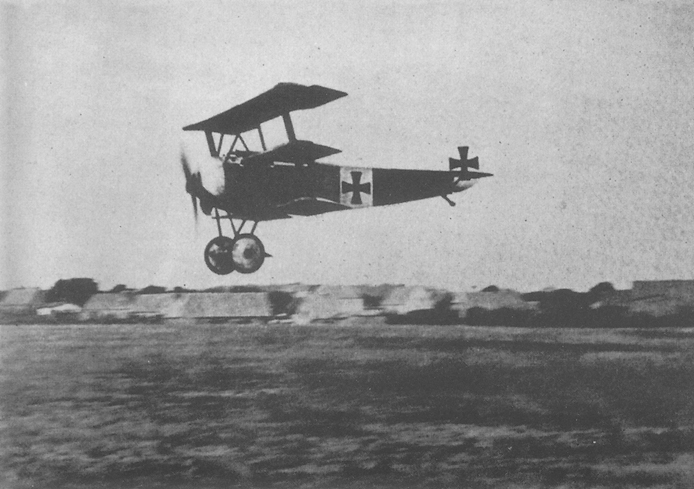

von Richthofen was killed in action in 1918 after recording eighty victories in the air

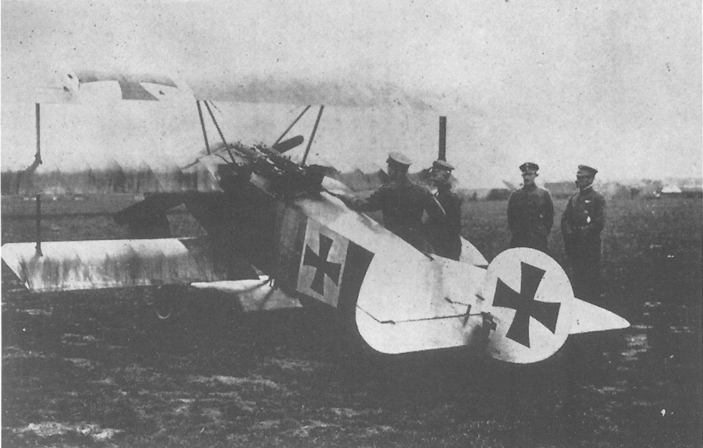

General von Hoeppner, Chief of the Imperial Air Force, talking with von Richthofen beside the latter’s machine

Oswald Boelcke, one of the first German fighter aces … killed in a collision during a dog-fight in 1916

left to right, Bruno Loerzer, who became a general in Goering’s Luftwaffe; Anthony Fokker, the designer, and Hermann Goering, who commanded the Richthofen Circus late in the First World War after Richthofen’s death

Peter Strasser, Commander of Naval Zeppelins until he was killed in action in 1918

Zeppelin ace Heinrich Mathy successfully bombed London on several occasions

Hugo Eckener, who developed the German airship fleet and pioneered the trans-Atlantic crossing

Ernst Udet, fighter ace during World War 1, stunt pilot and Luftwaffe general

the Heinkel He45, produced in 1933

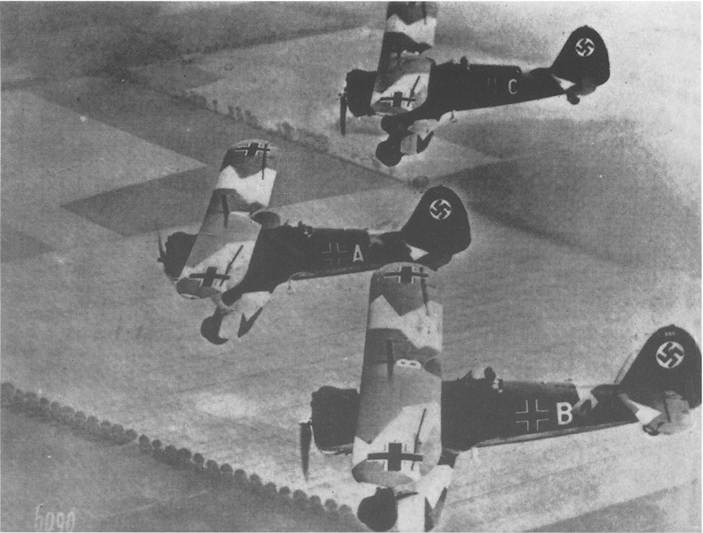

Henschel Hs123s appeared in the ’thirties as a ground-attack aircraft and were used during the early part of the Second World War. Goering later resurrected a squadron for service on the Russian Front

Hugo Junkers … inventor of the first all-metal aircraft

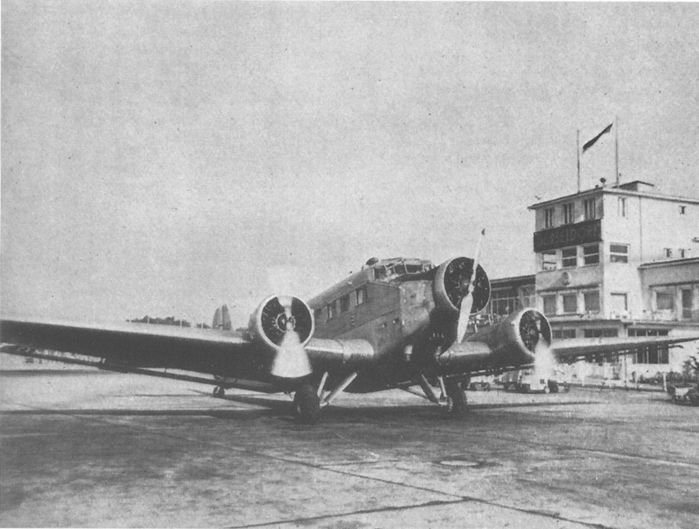

the Junkers Ju52/3m, an airliner version of the Junkers transport

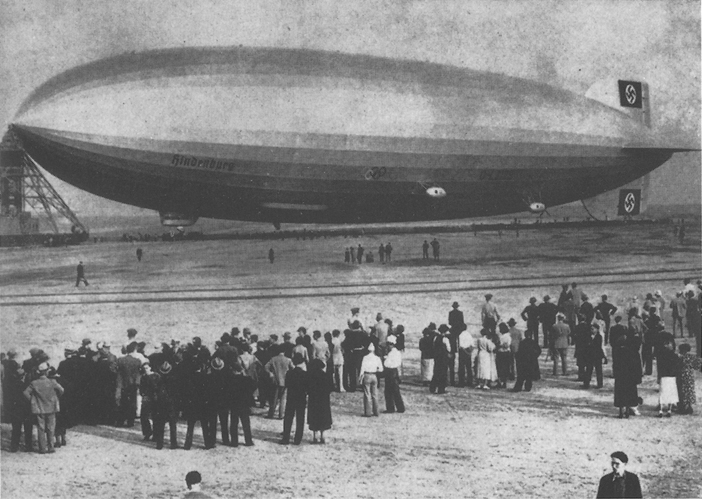

the last of the German airships: the Hindenberg. She is seen here in 1936 on her moorings at Lakehurst, N.J., above which she caught fire and was destroyed

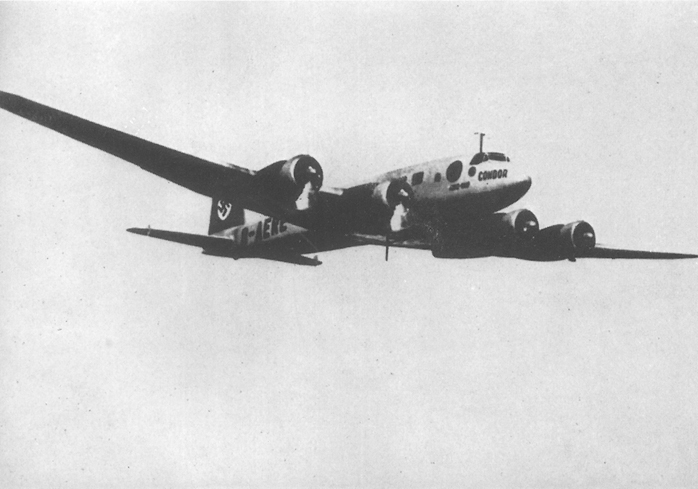

the Focke-Wulf Fw200, produced as an airliner in the ’thirties

reviewing the Richthofen Squadron at Staaken in 1935: Goering talks to Hitler with Erhardt Milch, then Secretary for Air, looking on (second from right)

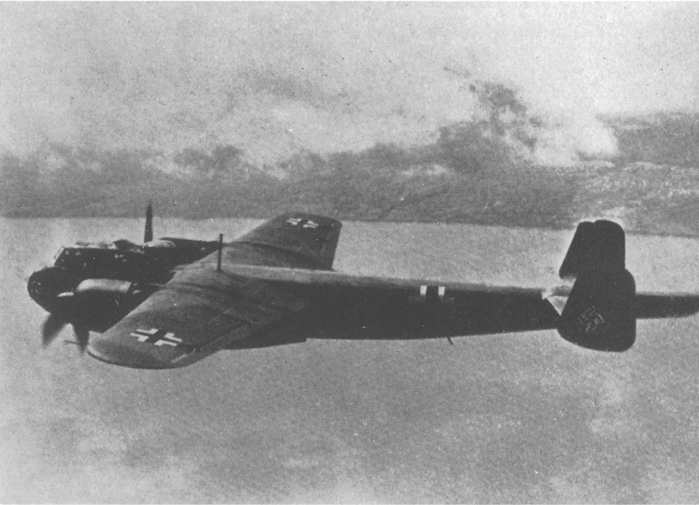

the twin-engined Dornier D0217, used throughout the Second World War as a medium bomber

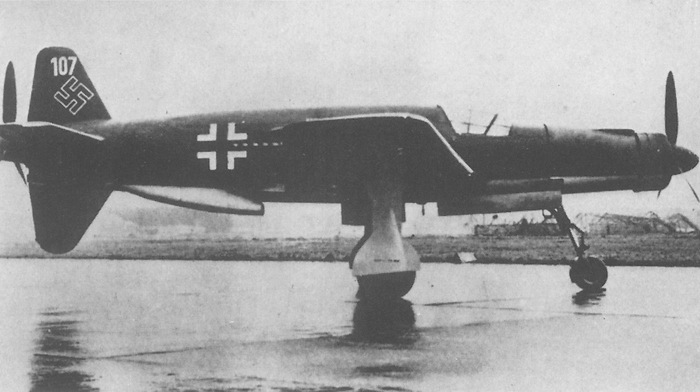

Two “Wonder Weapons” produced late in the Second World War: above, a tandem-engined Dornier D0335, used as a day fighter; below, a Junkers Ju88, mounted with an Fw190. The pilotless Junkers was filled with explosives and released over the target by the Focke-Wulf pilot

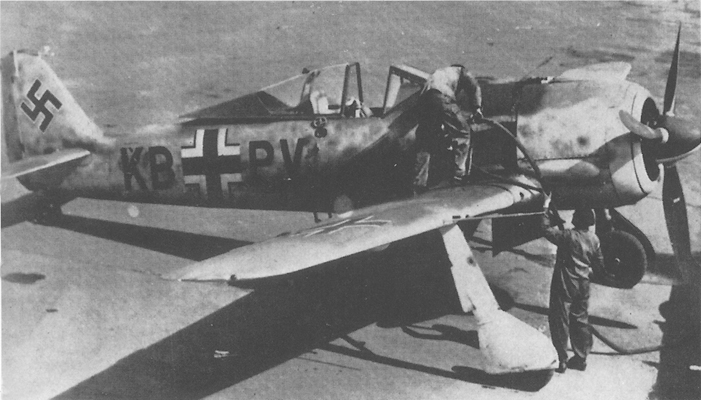

The Focke-Wulf 190, first German fighter to be designed with a radial engine. With the Messerschmitt Bf 109, often called the Me 109, below, it was one of the outstanding Luftwaffe aircraft of World War Two

the Bf 109E, an effective fighter-bomber in the Battle of Britain

another Battle of Britain fighter, the two-seater Me 110. After the Battle, in which it proved slow in manoeuvre, it became a night-fighter

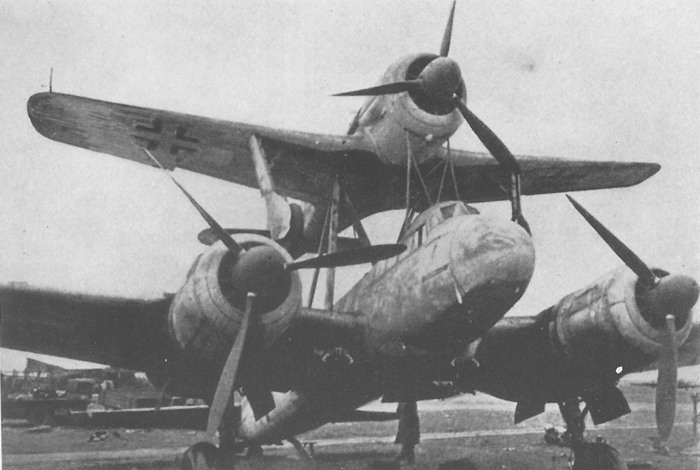

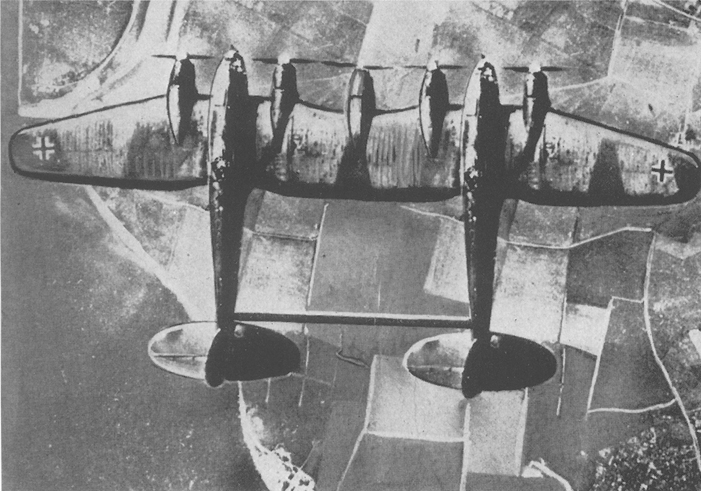

two Heinkel He 111s joined together and given a fifth engine. Intended as a glider tug, it did not live up to expectation and was never used to a great extent

the Junkers Ju87, or Stuka. One of the most successful dive-bombers in the early part of the war, it later proved unable to combat fighter opposition

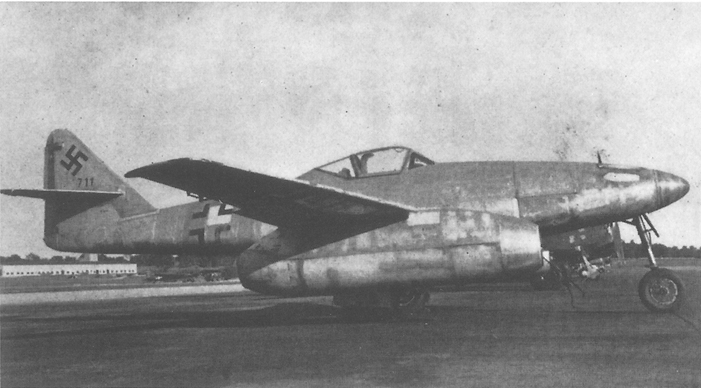

The first-ever operational jet fighter, the Me262, was produced in 1944 as a fighter, but Hitler destroyed its potential by using it as a bomber

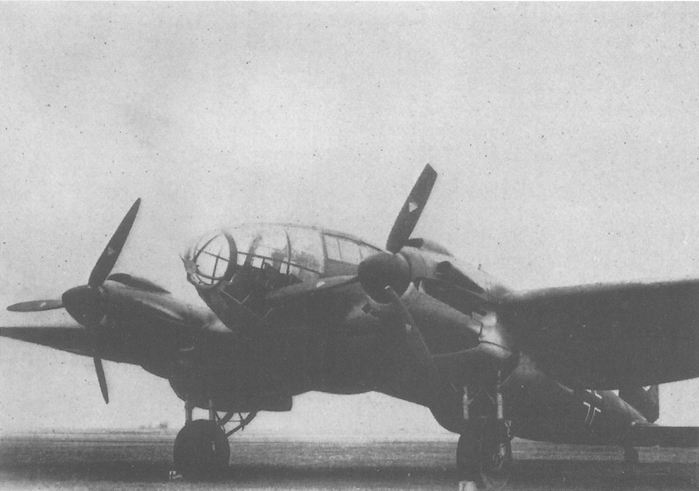

first used as a military bomber in the Spanish Civil War the He 111 saw service during the whole of the Second World War

General Hans Jeschonnek, Chief of Air Staff, right, with Field Marshal Kesselring centre

Adolf Galland, who became General of Fighters but was relieved of the position after a dispute with Hitler over the use of the Me262

the end of the Luftwaffe: a graveyard for German machines at Bad Abling

the end of Goering: seen here with an interpreter after the capitulation in 1945

The last mass daylight attack in any strength on London took place on 30th September, although the night Blitz against the capital—and also Liverpool, Birmingham, Coventry and many other cities continued without respite. The fifth, and last, phase of the Battle thus began on 1st October with a series of raids by bomb-carrying Bf 109s and 110s, leading inevitably to the first of the fighter-versus-fighter battles at great heights which typified the activities over England during the autumn of 1940. About a third of the German fighter force—some 250 aircraft—had been hurriedly converted to the fighter-bomber role in order to reserve the medium-bomber squadrons for night operations, but the fighter-pilots had little heart for undertaking a new task in what was obviously a “dead” offensive, with raids that, in the words of Adolf Galland, “… had no more than nuisance value.”

Galland, and also his contemporary Werner Molders, who had shot down forty-five enemy aircraft by early October, 1940, showed no hesitation in criticising Goering’s latest policy of using their fighter Gruppen as a makeshift bomber unit. Both these rising young aces had already incurred the displeasure of the Reichsmarschall more than once during the course of the Battle, Galland on a notable occasion when he had tried to point out the problems peculiar to the fighter arm, and Goering demanded at last to hear what he needed to Solve them. “A Gruppe of Spitfires,” Galland had replied calmly, a request the downright impudence of which it is not hard to believe “made even Goering speechless”. Now the arguments of Galland and Molders fell on deaf ears, the vast Reichsmarschall commenting angrily that the fighter arm had failed adequately to protect the bomber formations during the summer offensive, and if it was proving reluctant to undertake the fighter-bomber role it might as well be disbanded. He attempted to pour a little oil on the troubled waters by decorating both fighter leaders with Germany’s highest military award, the Oak Leaves to the Knights Cross, and conducting a stag hunt for their benefit at Karinhall, but they returned to their units in an unhappy frame of mind, comforted only by the knowledge that their daylight “nuisance” raids were enabling the night offensive to continue without respite.

On 12th October Hitler finally decided to bring the fiasco Sealion had become to an end. His invasion fleet had remained a priority target for Bomber Command during the late summer, with the result that much of the original assemblage had been dispersed and 214 barges and twenty-one transporters sunk in harbour, yet Hitler had insisted that a vast number of ships, men and equipment be kept at immediate readiness. At last, repeated pressure by Admiral Raeder and other commanders had its effect, and the Fuehrer gave permission for Sealion to be abandoned. “The Fuehrer has decided that from now until the spring,” wrote Generalfeldmarschall Keitel, “preparation for Sealion shall be continued solely for the purpose of maintaining political and military pressure on England….” This decision was followed by a vague statement about reconsideration of the invasion in the spring or early summer of 1941, but it was agreed that shipping should in the meantime continue to be released for other tasks, with only about a thousand barges to remain in the Channel ports for possible future use. Later, Hitler would disparage the importance of Sealion and comment that in his opinion the war against England was won in any case, but in fact he knew quite well that the moment for invasion had come and gone, and the opportunity would almost certainly never occur again. And yet, without a seaborne invasion England remained an impregnable island unable to be totally defeated.

The Battle of Britain thus drifted rather wearily to a close, an anti-climax that almost passed unheeded in the thunder of bombs falling night after night on London. In one of the last fighter battles of the year, on 28th November, Helmuth Wick, with fifty-six victories and then commander of the Richthofen Jagdgeschwader, was shot down and killed, probably by Flight Lieutenant J. C. Dundas of 609 Squadron, who also failed to return that day. Hauptmann Balthazar, a born leader and gifted fighter-pilot with over thirty victories, took over command of the Richthofen Geschwader, which by that time had accumulated a total score of five hundred enemy aircraft shot down since the outbreak of war. Despite heavy casualties in the Battle of Britain, morale remained high in the Geschwader; indeed, with so many brilliant pilots serving in the same unit it was unlikely to be otherwise, but some of the old confidence in an easy victory had gone, never to return again.

On the night of 29th–30th December, 1940, Hermann Goering brought the year to a blazing end with his heaviest attack to date on London during the hours of darkness. After an initial incendiary raid by Kampfgeschwader 100, which had gained considerable experience and notoriety as a “pathfinder” unit, large numbers of incendiaries, high-explosive bombs and parachute mines were dropped on the city by wave after wave of twin-engined bombers, causing no less than 1,500 simultaneous and uncontrollable fires. Insufficient water supplies and a lack of trained fire watchers seriously hindered the task of checking the inferno, and before morning the centre of London was a great heaving sea of flame, with the dome of St. Paul’s Cathedral rising like an island out of the smoke and gleaming like burnished gold against the crimson sky. If the Luftwaffe could have repeated its success that night with a series of similar raids, London, despite its famous slogan, would no longer have been able to “take it” but with the night blitz as with the daylight offensive there existed no definite plan. The smouldering capital staggered up from her knees to face the new year bloody but unbeaten, and grasped at the welcome opportunity to recover while Goering sat in Karinhall and debated on the best method of striking against England in the future.

For both sides, it had been a hard and bitter struggle. Between 10th July and 31st October the Luftwaffe had lost a total of 1,733 aircraft of all types, against 915 R.A.F. machines shot down. These could be replaced; but Germany and Great Britain had also lost many of their best airmen, most of them under the age of twenty-five, and these were irreplaceable. More often than not, they had been in service before the outbreak of war, and therefore were not “born into battle” like so many who followed, but entered it already grown to full stature. Only on the German side could it be said they had died in vain; they had come that summer in their hundreds, and in their hundreds they had been destroyed; the mightiest aerial army the world had ever seen broken by a thousand men who did not want war, but having had it thrust upon them willingly gave their young lives to end it.

Much has been said and written about those warm August and September days in 1940, but perhaps only one man was capable of summing up in a few words the great achievement that turned the bulky files so carefully compiled on Operation Sealion into so much useless paper, and in his wisdom he had chosen to utter them at the height of the Battle. “Never in the field of human conflict,” said Winston Churchill in the House of Commons on 20th August, “was so much owed by so many to so few.”